deep in his dreams, the lord was up and dressing for the hunt, as was every other man in the castle — servant, squire, and knight. Mass was said, as always. Straightaway afterward, they went to have their morning broth as the horses were readied in the snowy courtyard outside, the deerhounds gamboling at their feet, their tails waving, wild with excitement. Then, with the lord and his followers mounted, the whole company clattered out over the drawbridge, their hot breaths — horse, man, and hound alike — mingling in the frosty air.

Once the huntsmen were across the plain and into the woods, the horns sounded, sending the willing hounds to their work. They soon set up such a yelping and barking and baying that the whole valley resounded, sending shivers of fear into the hearts of every deer in the forest. Even as the deer heard it, they knew that there was no hiding place now, that speed was their only savior, that the slowest amongst them would surely die that day. So they ran for their lives, stags and hinds, bucks and does, flitting through the sunlit glades, leaping the roaring streams, clambering up rocky ravines, trying all the while to outrun the hounds, to shake off the hunters. But the deerhounds had seen them now and were hard on their heels. Waiting ahead of the deer, hidden in the forest, were the beaters, who, setting up a sudden terrible hullabaloo, turned them and drove them back toward the hunters’ arrows, toward the tearing teeth of the hounds. Time after time, the archers let loose their arrows, and another deer fell. Time after time, the hounds cornered an old stag and dragged him down. Hot with the chase but never tiring, the lord and his hunters rode on all day, following the deer wherever they fled, down deep wooded valleys, up over rocky moors. Many a deer died that morning, but many also were allowed to escape. The lord, as considerate a huntsman as he was a kind host, saw to it that they killed only the old and the weak and allowed the others to live on.

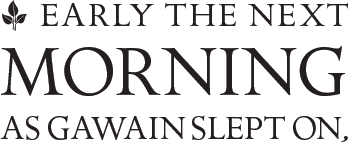

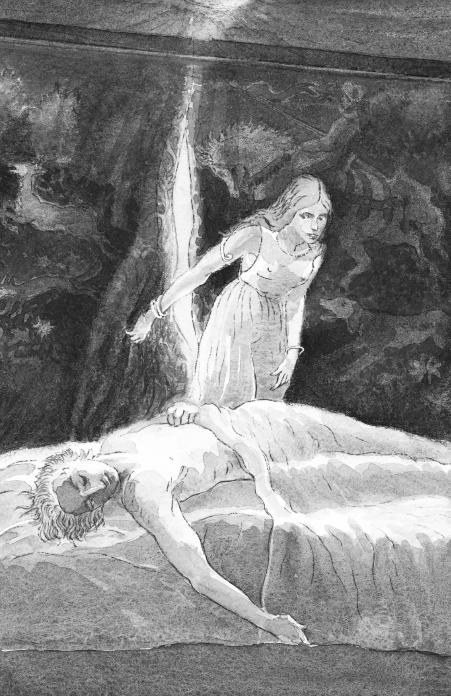

All the while, back in the castle Gawain slumbered on. Hovering on the edge of a dream, he was not sure at first if the footstep he heard was real or imagined. Waking now, he sat up and pulled back his bed curtain, just a finger’s breadth. The lady of the castle, that beautiful creature, was there in his room, in her nightgown. She was closing the door silently behind her. Quickly Gawain lay back again and pretended to be fast asleep. His heart beating fast, he heard the soft footsteps, heard the bed curtains being drawn back, felt the bed sag as she sat down beside him.

Now what do I do? thought Gawain. She cannot have come here simply to talk about the weather, can she? Perhaps I had better find out what she wants. So pretending he was just waking up, he turned on his back and stretched and yawned. Then he opened his eyes. He did his best to feign surprise, but he knew himself it wasn’t a very convincing performance.

“Awake at last, Sir Gawain! I never took you for a sleepyhead,” she began, her eyes smiling down at him. “So at long last I have you at my mercy.”

“If you say so, my lady,” Gawain replied, sitting up and trying to gather his wits about him as he was speaking. “You know I would do anything in my power to please you, lady,” he went on, struggling to find the right words. “But I think I should much prefer to get up and get dressed first — if you don’t mind, that is.”

“But I do mind,” she said reproachfully, and she shifted a little nearer to him on the bed. “I mind greatly. I have the great Sir Gawain close beside me. Do you think I would let him go? Would any lady let him go? I don’t think so. I know you are renowned throughout the land for your courtesy, your chivalry, and your honor. But my husband is off hunting with his friends, and after last night’s merrymaking, everyone else is still asleep. We are all alone.” She leaned over him, her lovely face, her soft skin close to his.

“Lady,” he replied, “I’ll be honest with you. God knows I’m not nearly as honorable as I’d like to be, or as I’m made out to be. I wouldn’t ever want to upset you, dear lady, but why don’t we just talk? I like talking. I’m good at talking. I can be funny, serious, charming, or thoughtful — whatever you like.”

The lady laughed, took Gawain’s hand, and drew him closer again. “Dear Gawain,” she said, looking deep into his eyes so that his heart all but melted, “there isn’t a lady in this land who wouldn’t die to be where I am now. In you I have everything a woman could desire — beauty, strength, charm. You are as truly courteous and chivalrous a knight as I have ever known.” She sighed longingly and caressed him so tenderly with her eyes that Gawain almost gave in.

“I am very flattered, lady, that you should think so highly of me. I will try therefore to live up to these high ideals of knighthood you say I possess, and to which certainly I aspire. I will be your servant and your true knight, not wanting ever to hurt you or harm you in any way, or ever to take advantage. I want only to protect you.”

At this the lovely lady threw up her hands in despair. “Gawain, you disappoint me,” she said. “But I’m not leaving this room without a kiss. As my knight you owe me that at least. Deny me that, and you would hurt me deeply.” One kiss, thought Gawain, where’s the harm in that? As long as I don’t enjoy it too much, it will be fine.

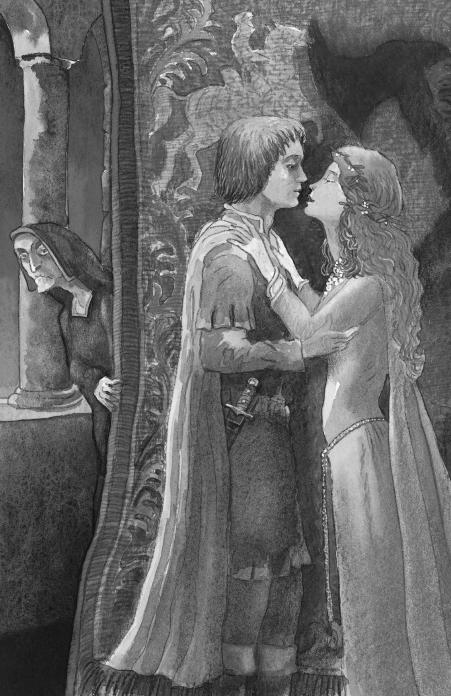

“As your knight I would never want to hurt you, lady,” Gawain replied. “As your servant I will obey, willingly. Kiss away, my lady.” And so she kissed him long and lovingly and then quickly left the room.

Stunned by the kiss, Gawain sat there confused, relieved she was gone and yet longing for a second kiss. He washed and dressed swiftly and went downstairs, where all the ladies were waiting for him. He had a dozen other ladies looking after him that day, as well as the lady of the castle. They tended to his every need, so as you can well imagine, Gawain had a fine time of it. But wherever he went, whatever he did, he felt that ancient crone, that wrinkled hag, always watching him — and usually from somewhere behind him, so that by the end of the day Gawain had a dreadful crick in his neck.

As the sun set through the windows of the great hall, they heard the drawbridge go rattling down. Rushing to look, they saw the hunters spurring into the darkening courtyard, their horses’ hooves sparking as they struck the cobbles. Great was the excitement when into the hall strode the lord of the castle, mud-spattered from the hunt, a huge deer slung over his shoulder. This he laid down at once at Gawain’s feet. “Here you are, Gawain, my friend,” he cried triumphantly. “Look what I have for you. I have twenty more like this, and all of them are yours, as I promised. Well? How do you think I have done?”

“Wonderfully well, my lord,” Gawain began, choosing his words carefully. “But I am afraid you’re going to be very disappointed in me because all I have to offer you in return is this.” And with that, Gawain stepped forward, put his arms around the lord of the castle, and kissed him once on the cheek, very noisily so that everyone could hear it.

Laughingly, the lord wiped his cheek with the back of his hand. “Well, it’s better than nothing, I suppose,” he said, “but I’d have enjoyed it all the more if I’d known how you came by such a kiss.”

“That you will never know,” Gawain replied. “It wasn’t part of our agreement. I did not ask you how you killed your deer, did I? No more questions, my lord. You have had all that was owing to you, and that’s that.”

“Fair enough, my friend,” said the lord of the castle. “I’m starving. I shall bathe first. Then we shall eat and drink and be merry again.”

Long into the night, the two of them ate and drank and talked together and laughed. Then, over the last goblet of wine — and sensibly they had left the finest wine till last — the two knights made again exactly the same pact between them for the following day. “And I’d like something a bit more interesting this time if you can manage it,” laughed the lord of the castle as they went upstairs to their rooms.

“I’ll do my best,” said Gawain. “I promise.”

By the time the cock had crowed three times, the lord was out of his bed and dressing. As before, Mass was said, and a quick breakfast taken. Then the lord and his huntsmen were out in the cold gray of the dawn, mounting up and eager to be gone once again. The hounds too were keen to be off, their noses already scenting the air. Upstairs in his bedchamber as the hunt rode away, Gawain heard none of this. He was dead to the world, sleeping off the heady excesses of the night before.

Far over the hills, the hunting party went into a deep valley of thorns and thickets, where they knew the wild boar roamed. It wasn’t long before the hounds picked up a scent and gave voice, their howls echoing as loud as the huntsman’s horn so that the whole valley rang with the terrible din of it. Baying in chorus, the bloodhounds splashed on through a murky bog toward an overhanging cliff face, at the foot of which lay great piles of tumbled rocks and rugged crags. Here they stopped and bayed so dreadfully that the huntsmen knew the beast must be hidden in there somewhere, deep in some cave or cleft, but neither man nor hound dared go in after him.

Then one of those dark rocks seemed suddenly to heave itself to life and become a raging boar. Out of nowhere he came, charging straight at them, the biggest boar the lord had ever seen, and the meanest too. At a glance the huntsmen could see he was old — he had to be, with tusks as huge as his. If he was old, then he must be wily too, and this one was still nimble on his feet. Truly a formidable foe, this bristling monster, enraged at his tormentors, tossed his tusks furiously at the bloodhounds as he came toward them, and threw them aside as easily as if they had been helpless pups. And believe me, those he caught on the points of his tusks never rose again, but afterward lay there dead and bleeding on the ground, a piteous sight. Bravely the hounds leaped at him and bravely he defended himself, spearing through the first one, then another, so that soon the pack bayed for blood no more but moaned and whined in its fear and grief, and hung back, unwilling to attack this monster again. In desperation, the huntsmen tried shooting at him with their bows, but the arrows simply bounced off his bristling hide. They hurled their spears at him, but every one of them splintered on impact.

Now hunters and hounds both stood back, gazing in awe at this invincible beast as he escaped from them yet again, and wondering if at last they had met their match. But without a thought for his own safety, the lord went after him, charging through the thickets and hallooing so fiercely that, seeing his courage and determination, the huntsmen and the bloodhounds followed. This hunt was not over yet.

Back at the castle, Gawain lay awake, but sleep was still in his head. What happened next he half expected. He heard the door open and the lady steal softly toward his bed. This time at least he was ready for her. As she parted the bed curtain, he sat up. “Good morning, my lady,” he said cheerily.

She sat down beside him and stroked his brow softly. “What? Just good morning?” she wheedled. “Is that all I’m worthy of? Did I teach you nothing yesterday? Did we not kiss then, and now it is just ‘good morning’?”

“Lady,” Gawain replied, “It is not for me to offer to kiss you. If I tried to kiss you and you did not want it, then I’d be in the wrong, would I not?”

“How could I ever not want it?” she said, playing him with her shining eyes. “And even if I didn’t want it, I could hardly stop you from kissing me, could I?”

“I would never do that,” Gawain protested. “Where I come from, no knight ever threatens a lady with force. But if you really want to kiss me, then please don’t let me stop you. After all, a kiss from a lady to her knight is quite acceptable.” So the lovely lady leaned toward him and kissed him so sweetly that Gawain almost swooned with the joy of it. He wanted it never to stop. But stop it must, before it was too late. Breathless, Gawain pulled back and held her at arm’s length. “Look,” he said, “why don’t we just talk? It’s less dangerous.”

“Oh, Gawain,” complained the lovely lady. “Sometimes I’m not sure I believe you are Sir Gawain at all. You are supposed to be the most chivalrous knight in the entire world. Isn’t the sport of love among the most important of all the arts of chivalry? Doesn’t a true knight fight for his love? Or have I got it wrong? Yet you sit there and say no words of love to me. Just to get a kiss out of you is like getting blood out of a stone. Is it that you don’t like me? Am I not attractive to you, is that it?”

“Of course I do. Of course you are,” Gawain replied.

“Then what are you waiting for?” she said, exasperated. “Here I am. My lord has gone hunting. We are alone. Teach me all you know of love, Gawain.”

Now Gawain had to reply with all the skill and tact he could command, for he had to put her off without displeasing her, and that was not going to be easy. “Fair lady,” he began, “just to have you near me, and to look at you, is enough. But as for the sport of love, I think you’re much more skilled in that than I am. In that regard I’m just a clumsy knight, but I am a knight all the same, who must live in honor or die in shame. Having my honor always in mind, I will do all I can to please you.”

Still she stayed and tried to tempt him more, and again he resisted — but it was hard. In time, though, it became a game between them, a sport they both enjoyed, and at the end of it, neither was the winner. But there was no loser either, so they could both be happy. They parted in friendship and love — and with a kiss so long and languorous that for several minutes after the lady had left, Gawain’s head was still spinning.

He took his time getting up, for there was no hurry. Afterward he went straight to Mass and prayed for God to give him strength to resist the lady, and also strength to face up to the trial he knew he must soon endure in the Green Chapel. All day long, this fateful confrontation was in the back of his mind, but fortunately there were plenty of pleasant distractions to occupy him — particularly the ladies of the castle, who again did all they could to entertain him. Even that wizened old crone gave him a smile. Not a pretty smile, it’s true, but a smile all the same.

While Gawain luxuriated in all these creature comforts and delights the lord of the castle was still out chasing his fearsome boar. Over hills and dales, the hounds and huntsmen chased that beast. Yet strong though the boar was, he tired at last and knew his legs could carry him no farther. On the banks of the rushing stream he made his last stand. Setting his back in a cleft in the rocks, he dared them to come on. Foaming at his mouth and snorting his defiance, he faced them, pawing the earth in his fury and tearing at the ground with his terrible tusks. On the other side of the stream, the huntsmen hesitated. They whooped and hallooed at the bloodhounds to keep them at their task, but like their masters, none had the strength or courage to close and make the kill.

Only the lord himself dared try to finish it. Dismounting from his horse, he drew his great sword, and striding through the stream, he ran at the beast, who had only one thought in his mind — to hook his tusks into this man’s body and kill him before he was killed himself. Out he charged, head and tusks lowered. Sheer speed and power took the lord by surprise. Hitting him with all his force full in the chest, the beast caught the lord off balance and sent him sprawling so that the two of them tumbled backward together into the stream. Luckily for the lord, the tusks had not dug too deep into his flesh but only gashed him slantingly. Luckily too for him, but not for the boar, the beast had charged onto the point of the sword, which passed clean through his heart, killing him at once.

As the boar was swept away downstream, his teeth still bared with the fury of his last charge, the huntsmen came to their lord’s aid. Dazed and bleeding, he was nearly drowning when they dragged him out. It took a while for them to retrieve the boar, for the stream was fast and had carried him far, and, the beast being even heavier now in death, it took a dozen strong men to haul him up onto the bank. Lord and huntsmen gazed down at their quarry and shook their heads in wonder, for this was truly a giant among boars. Dead though he was, the whining bloodhounds would not go near him even now, still fearful perhaps that the beast might rise phantomlike to his feet and come after them once again.

Back at the castle, dallying contentedly on cushions before the fire, Gawain and the ladies heard at last the sound of the hunt returning, the hunting horns resounding in triumph as the huntsmen rode laughing into the courtyard. They knew the hunt had been successful, but none could have imagined what they were about to see. When the lord, blood-spattered and mud-spattered, came striding into the hall, that was alarming enough. Then they saw the servants behind him come staggering in carrying between them, dangling from a pole, the most gruesome sight they had ever seen — a bristling monster of a boar. He looked so evil and ferocious even in death that many ladies there had to look away, fearing this ghastly creature might be some incarnation of the devil himself.

“Here you are, Gawain, my friend,” said the lord, beaming proudly. “He’s yours, my gift to you, as I promised you. Is he big enough for you? Have we done well?” Gawain walked all around the great beast, marveling at it.

“What a splendid creature!” he breathed. “And what a huntsman you must be. But there’s blood on you, my lord. Are you hurt?”

“Just a scratch,” said the lord of the castle. “I was lucky. It could have been a lot worse.” And smiling, he went on, “And how about you, Gawain? Were you lucky today? What have you got to give me in return for this magnificent beast?”

“Not a lot,” Gawain replied. “Just this.” And, laughing, he stepped forward and kissed the lord twice, once on each cheek. “That’s it, I promise you,” Gawain shrugged. “And to be honest, my lord, I’m glad it wasn’t more, because as much as I like you, I really don’t like kissing men with great bristly beards!” At that the two friends laughed out loud, as did everyone else in that great hall, except for the unfortunate boar, of course.

All evening the laughter went on: as the boar’s head was brought in at dinner, an apple in his gaping mouth; and as they drank and danced and sang the night away. But fun though it was, Gawain could not enjoy himself fully, for with the lady of the castle constantly at his side and making eyes at him he had always to be on his guard. She doted on him so openly, so obviously, that Gawain thought it must surely soon offend the lord of the castle. But much to Gawain’s relief, the lord seemed not to notice at all what was going on. He was wrapped all the while in conversation with the hideous old hag, who even as she was talking to him, still eyed Gawain, smiling toothily at him, as if she knew something that Gawain didn’t. Gawain found them both, hideous hag and lovely lady, unnerving and deeply unsettling.

Although Gawain managed politely to keep that lovely lady at bay all evening, he could feel those pleading eyes slowly weakening his will to resist. He made up his mind to leave the castle the next morning and be on his way before he did something he would regret. He stood up. “Dear friends,” he said, “I do not want to break the spirit of this feast, but I have stayed long enough and really think I should be off tomorrow morning.”

“Nonsense!” cried the lord. “You shall do no such thing. I’ve told you, my friend, the Green Chapel you seek is only a few miles away. You can stay all day tomorrow, leave the following morning, and easily be on time for your meeting at the Green Chapel. I shall be very hurt if you leave us before you need to. So will my wife and everyone here, too.”

There was such a clamoring for him to stay that Gawain knew he could not refuse them. “I don’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings — and certainly not yours, my lord,” Gawain said, “not after all you have done for me. So I shall stay as you command me.”

“A wonderfully wise decision, Gawain,” said the lord, “and all the better because it will give us another chance to play our game one last time, won’t it? I’m off hunting first thing tomorrow as usual, so you can stay here and enjoy yourself as you will. When I get back in the evening, we shall see what I have for you and you have for me. And Gawain, my friend, all I’ve had from you so far in this game is kisses. How about something different for a change?”

“I’ll do my best,” replied Gawain. But although he was laughing with everyone else, he was not at all happy to be playing the game again. He knew the risks that came with it.

“And now to bed,” said the lord, yawning hugely. “I shall sleep like a log tonight.”

So off they all went to bed, the servants lighting their way upstairs. The lord did sleep soundly, but for most of the night, Gawain hardly closed his eyes at all. He lay there troubled mightily by all the trials and temptations he knew the next day would bring, and fell into a heavy sleep at last just as dawn was breaking. He heard nothing of the hunt gathering in the courtyard below his window, nothing of the yelping of impatient foxhounds, or the snorting and stamping of horses eager to be gone. Gawain slept through it all.

The lord of the castle, refreshed from his night’s sleep, rode hard across the fields, his huntsmen and hounds behind him. And what a beautiful morning it was too, with the clouds above them and the ground beneath them rose pink with the rising sun. But the fox cared little about that, for he had already heard the dreadful baying of foxhounds hot on the scent, and wanted only to put as much distance between them and himself as he could. The fox was fast too, faster than any hound and he knew it, but he also knew they were stronger than he was, that hounds did not tire as he would. Speed might help him, but only his cunning could save him. So he darted this way and that to bewilder them, weaving and doubling back on himself in amongst the rocks, fording as many streams as he could find, all to outwit the hounds and put them off the scent. Time and again he thought he had escaped them, but the hounds were not so easily fooled, and with so many noses to the ground, they soon picked up his scent again and gave voice to tell him so.

As he slowed, they came on still faster, all in a pack, the huntsmen sounding their horns and hallooing loud so that the valleys rang with the song of the hunt, a song no wild creature ever wants to hear, the poor fox least of all. On he ran, his heart bursting, desperate to escape, to find some bolthole to hide where the hounds would not find him. But he was out on the open plain now, where there was nowhere to hide. All he could do was run. Catch me they may, thought the fox, but at least I’ll lead them a merry dance before they do.

Gawain slept late that morning. He was deep in dreams when he felt a sudden shaft of brightness falling across his face. The lady of the castle came out of the sunlight, out of his dreams, it seemed, toward the bed, smiling as she came. “What? Still asleep, sleepyhead?” she laughed gaily. “It’s a lovely morning out there. But, to be honest, I’d far rather be in here with you.”

Still trying to work out whether he was dreaming or not, Gawain saw that she was not wearing the same nightgown as before but a robe of finest shimmering silk, white as cherry blossoms and trimmed with ermine. She wore dazzling jewels in her hair and around her neck. She had never looked more beautiful. This time there was no preliminary banter whatsoever. She came straight to him as he lay there and kissed him at once on the lips. Now Gawain knew he really was awake. Her kiss was so inviting, so tantalizingly tender. “Oh, Gawain,” she breathed, “forget you are a knight just this once. Forget your chivalry and your honor.”

It was lucky for Gawain that she had reminded him at that moment of his knightly virtues. “Dear lady,” he said, desperately trying to rein himself in. “You have a gentle lord as a husband, who has shown me nothing but the greatest hospitality and friendship. I would not and I will not ever cheat him or dishonor him. We can talk of love all you want, lady, but that is all.”

“It is not talk I want,” the lovely lady protested. “Let this opportunity pass, Gawain, and you will regret it forever. Or is it perhaps that there is someone you already love more than me, someone you are promised to? Tell me the truth, Gawain.”

“No, fair lady, I am promised to no one. And the truth is that although I have never in my life known anyone fairer than you, I do not want to promise myself to anyone just yet, not even you.”

At this she moved away from him, shaking her head sadly. “How I wish you had not said that, dear Gawain,” she sighed. “That’s the trouble with truth — it cuts so deeply. But I asked for it, so I mustn’t complain. I see now that I cannot hope to alter your mind or your heart. But couldn’t you, in knightly courtesy, and still protecting your honor, couldn’t you at least give me one last kiss? As friends?”

“Why not?” replied Gawain. “After all, a kiss is just a kiss.” And she leaned over him and kissed him so gently, so softly, so sweetly, that Gawain very nearly forgot himself again.

“One last thing,” she said, getting off the bed. “Will you let me have something of yours to take away with me, to remember you by, a token of some kind, a glove perhaps?”

“But I have brought nothing worthy enough to give you, dear lady,” Gawain replied. “I wish I had, but I cannot give you just a dirty old glove. A lady like you deserves only the best, and I would far rather give you nothing at all than something unsuitable or insulting. Why don’t we instead simply treasure the memories we have of one another? I shall not forget you, fair lady, I promise you that.”

“Nor I you,” replied the lady. “But all the same, it would please me so much if you would accept this memento of our time together.” And taking a ruby ring off her finger, she offered it to him.

“I cannot take this, sweet lady,” said Gawain, although he was touched to the heart by the generosity of this gesture. “If I can’t give you a gift, then I must not accept one, and certainly not one as precious and valuable as this.” She tried again and again to persuade him to take it, but he refused her every time, politely but firmly.

She wasn’t finished yet, though. “All right then,” she said at last, “if you won’t take this, then will you instead accept something more simple, perhaps, something that has no real value at all but will remind you of me whenever you see it? Please, Gawain, it is only a little thing.” With that she took from around her hips a wonderful belt of green silk richly embroidered in gold. “Take this, dear Gawain,” she pleaded. “It’s not much, but I have always worn it close to me. So if you were to do the same, I should in some way always be close to you. Do it for my sake, to please me.”

“Dear lady,” Gawain replied, “I do not want to upset you, believe me, or to part on bad terms. You call this a little thing, but yet it is a pretty thing, and I can see that it has been exquisitely crafted. It is still far too generous a gift when I have none for you in return.”

“This is more than a pretty thing, you know,” the lady replied. “It was woven by an enchantress so that whoever wears this belt can never be killed, not by a witch’s cunning spells, or by a dragon’s raging fire, or by the strongest and most deadly knight in all the land. Wear this belt around you, Gawain, and you are truly safe from all dangers.”

“All dangers?” Gawain asked her, pondering hard on everything she had just told him.

“All dangers, I promise you,” said the lovely lady, dangling the belt before his eyes.

This is too good to turn down, thought Gawain. If what she says is true, then I could wear this belt when I meet the Green Knight, and no matter what happens, I need not die. This belt would protect me.

The offer was just too timely, too tempting. So at last he accepted the gift, taking it from her and thanking her from the bottom of his heart. “I will wear it always, and whenever I put it on, I promise I will think of you.”

“Then I have won a little victory at last,” laughed the lady, clapping her hands in joy. “I am so happy. But I have one very last favor to ask you, Gawain. You won’t ever tell my lord and husband about this gift, will you? It might make him very jealous. It must be our secret, and our secret alone. Do you promise?”

“I promise, fair lady,” Gawain replied. Although he did not feel at all comfortable about any of this, neither the gift nor the promise he had made, yet he did feel a lot easier in his mind about his encounter with the Green Knight the next morning.

The lady of the castle gave him one last kiss, and left him clutching the belt tightly and relishing again the three sweet kisses she had given him that morning. It was midmorning by now, so hiding away the silken belt under his mattress, where he could find it later, Gawain dressed quickly. Then straightaway he went down to Mass, and afterward confessed all his sins — of which, as we know, there were more than usual that morning. So, freed of all cares now by both priest and belt, lucky Gawain was able to pass the rest of his day mingling with the ladies of the castle, who kept him more than happily occupied. He was so absorbed by the charm of their company that he scarcely gave a thought to what lay ahead of him the next day.

Out on the plain, the poor old fox was not having such a happy time. He knew in his heart that his running days were over, but as every living creature will do in the struggle to survive, he tried his utmost to cling onto life as long as he could. Often he went to ground and lay there in the earthy darkness, his frantic heart pounding, hoping each time that the hounds would pass him by. But foxhounds carry their brains in their noses. No fox’s scent ever escapes them. Once discovered, the fox lay low in his den for a while as the hounds gathered outside, baying for his blood, scrabbling at the earth to dig him out.

There are always many ways out of a fox’s den. Maybe he would find some unguarded exit and then make a run for it, bolting off as fast as his legs could carry him. But, weakened as he now was, he was not fast enough, and the hounds were running more strongly than ever as they closed in for the kill.

Poor Reynard. He made it to one last earth, and as he lay there, he knew he could run no more. He had two choices: to wait there in terror only to be dug out and torn to pieces or to end it now and get it over with. His choice made, the brave old fox darted up the tunnel into the light, and there the lord of the castle was waiting, his sword at the ready to spear him through. So mercifully the fox found the speedy death he had sought. The huntsmen cheered wildly as the lord held the fox up high by his tail while the hounds howled at the lord to be given their prey. But the lord bellowed loud above their baleful baying. “Not for you, my friends,” he cried. “This one I shall keep for Gawain.” So instead of the meat and skin and bone they craved, he gave them laughingly a pat on the head, then mounted his horse again and rode home across the wide plain, the setting sun making long shadowy giants of men and horses and hounds alike.

Once back in the castle the lord strode at once into the great hall, the fox limp in his arms. Straight up to Gawain he went. “He may not look like much to you,” he said, “but I can tell you, this cunning old fox led us a merry old dance all day long. So he’s all I’ve got to show for a whole day’s hunting, and he’s yours, of course, as I promised. I’m just hoping you did a lot better today. What is it you have for me? Something special I hope. All I’ve had so far is kisses.”

“I’m sorry to say, my lord,” Gawain replied, laughing, “that kisses are all you’ll get today as well because they’re all I got: but there is at least some good news for you because today I’m going to give you not one, not two, but three!” And saying this, he put his arms around the lord of the castle and kissed him affectionately and noisily three times, each time trying to avoid his bristling beard.

“I mean no offense, Gawain,” said the lord, “but I have to say that I think you’ve had rather the better of our little game. But then I shouldn’t grumble, for we both played by the rules, did we not?”

“We did,” Gawain replied, but as he spoke he found it hard to look his friend in the eye.

That last evening they laid on a magnificent feast for Gawain. The whole castle resounded with caroling and dancing, and as they sat at the table, joyous laughter rang through the rafters. Succulent venison they ate, and crackling pork and all manner of spicy soups that warmed Gawain to the roots of his hair and set his scalp tingling. All evening long, every heart was alive with joy. No one ever once scowled or frowned, not even the usually surly old hag who seemed always to skulk about the castle. She drank her fill like everyone else, and smiled often at Gawain. But Gawain still found her a very troubling presence because when she smiled at him, her eyes seemed to look right through him and see into his soul, where all his darkest secrets lay.

By now Gawain knew that he had had more than enough to drink and that he must say his farewells whilst he still had his wits about him. He stood up and lifted his goblet in a toast to all his new-found friends around the table. “May God bless you all for your many kindnesses to me these last few days,” he said. “I have spent the most wonderful week of my life with you, basking in the warmth of your company, and I shall never forget it. I’d stay with you if I could, sir, you know I would. I don’t want to go at all, but I must. I am a Knight of the Round Table, and tomorrow I have a promise I must keep. So if you will, lend me the guide you offered me and let him show me the way to the Green Chapel, where I must face whatever God decides my fate should be.”

The lord now also rose to his feet, and put his arm around Gawain’s shoulder. “Like you, Gawain, I always keep my promises,” he said. “You shall have your guide. He will be ready for you at dawn tomorrow. It is all arranged. He won’t get you lost. Don’t you worry. We’ll get you where you have to go.”

Then each lady in turn said her sorrowful goodbye to Gawain, kissing him fondly — even that ancient crone had her turn. Then came the lady of the castle, who kissed him most tenderly, looking lovingly into his eyes one last time. The knights too came to embrace him, all of them wishing him good luck and Godspeed, until at last only the lord of the castle was left. “God keep you safe tomorrow, Gawain,” he said, “and until we meet again.”

Gawain was lost for words as they embraced each other lovingly and parted. Then he stood alone in the empty hall before the dying fire and could think of nothing now but his meeting with the Green Knight the next day. He drank more wine, but even wine could not put it out of his mind. Maybe the silken belt is not enchanted at all, he thought. And even if it is, will it be strong enough to save my neck? Have I the courage to go through with this? Must I do it? Once Gawain was in his bed, these questions would not leave him, would not allow him the blessed oblivion of the sleep he longed for. All that long night he lay awake, hoping and praying most fervently that the green silken belt would save his neck, for he knew nothing else could.

The first crow of the cockerel sent a shiver of fear through him, but he clenched his jaws and his fists, gathered all his courage, and determined there and then that he would see it through to the end, whatever that end might be. I have looked death in the face before, and without flinching too, he thought. I can do it again. I must or never again call myself a knight. So, keeping that thought firmly in mind now, Gawain got himself up and dressed and ready.

Outside his window, the snow had fallen all around, silencing all but the crowing cockerel, and even his coarse cry was dulled and deadened by the snow. Servants brought him his mail coat first, cleaned now of any rust, and his body armor, as bright and shining again as it had been when he’d first set out from Camelot. Then he put on once more his scarlet surcoat, fur-lined to protect him against the cold — and of course he did not forget the green silk belt the lady had given him. This he wound securely around his waist, also for protection — not from the cold, but from death itself. He looked fine in it too, the gold thread of the belt glittering in the early sun that now streamed in through the window. It suits me well, this belt, thought Gawain, but I shouldn’t care about what it looks like. It’s the magic in this belt that I need, not its beauty.

When Gawain came downstairs, the guide was waiting as promised and Gringolet was already saddled in the courtyard. The horse had been well fed and rested in his stable all this time, so his coat shone with health. He was fit and fiery again, fretting feverishly at his bit and tossing high his handsome head. Gawain could see his horse was itching to be off. Once Gawain was mounted, he was handed his helmet and his shield, his sword and his spear. Gringolet was pawing the ground still, but Gawain held him back for a moment. “God keep all who live in this place,” he said, looking up at the castle. “May he bless you for all your many kindnesses shown to me, a stranger. Lord and Lady both, I wish you happiness and good fortune on this earth, and afterward the place in heaven you both so richly deserve.”

Now, as the drawbridge rattled down, he let Gringolet go at last. No spurs were needed, no squeeze of the legs. Gringolet leaped forward, sparks flying from his hooves, and galloped away over the drawbridge and out onto the snowy plain. Watching him go, the porter at the gate crossed himself three times and commended Gawain to God, for like everyone in the castle, he knew what lay ahead of the knight that day and feared for his life.

Catching him up after a while, the guide led Gawain on more slowly now, through the mantle of freshly fallen snow. Soon their way took them up into inhospitable hills, where an icy wind chilled their faces, then higher yet onto craggy moorland, where mists hung dark about them. They trudged through stinking bogs, they waded through roaring rivers, until at last they found themselves passing under high overhanging cliffs and into deep dark woods, where the wind whistled wildly through the branches above them.

When at last they rode out of this dreary place and into the sunlight, Gawain saw that he was on the crown of a hill, below which a sparkling stream flowed gently by. Here the guide, who until now had not spoken a word, reined in his horse and turned to speak to Gawain. “This is the place, Sir Gawain,” he said, and his voice trembled with fear as he spoke. “Follow that stream, and it will lead you to the Green Chapel and the fearsome knight who guards it. No bird sings there. No snow ever falls. No flowers bloom.” Gawain thanked him and made to ride on, but the guide grasped at his reins and held him back. “If you’ll take my advice, Sir Gawain — and I know it is not my place to give it — you should not go any farther. I have too much respect and love for you to let you go on without warning you. The man who awaits you is the most terrible knight alive, a real butcher, I promise you. He is not just the strongest knight that ever lived, but the most savage, the most vicious. He loves to kill and is very good at it too, believe me. No man who has visited the Green Knight of the Green Chapel has ever lived to tell the tale. It’s always the same. We find their bodies downstream, hacked and hewn to pieces. He shows no mercy to anyone, Sir. Page boy or priest, they’re all meat to him. He’ll feed you to the fishes, sir, like all the others. So don’t go, I beg you.” And now he spoke low, in a confidential whisper. “Listen, Sir Gawain. Why not go home another way? No one’ll ever know. I shall tell no one that you changed your mind and thought better of it. Your reputation is safe with me, sir.”

“Thanks all the same,” Gawain replied, “I know you have only my best interests at heart, and I am grateful to you for that, but I’ve come this far — too far to turn tail and run now. I’m sure you would keep my cowardice a secret, but I would know, and I would not be able to live with myself. I am a Knight of King Arthur’s court, and I have to keep the promise I made, even if I do end up as food for the fish. My courage is fragile enough as it is, so please don’t try to talk me out of it anymore.”

“I have done all I can to save you,” said the guide, sighing sorrowfully. “If you insist on going to your certain death, Sir Gawain, then I cannot stop you. To find the Green Knight, just ride along the stream until you see the Green Chapel on your left. Cross the stream and call out for him. He’ll come. And then, God help you. No one else can. I shall leave you here, sir. For all the gold in the world I would not go where you are going. Goodbye, Sir Gawain.” And touching his heels to his horse, he rode away and left Gawain alone. Talk is easy enough, Gawain thought, but now I must be as good as my word and try to be the kind of knight I claim to be and others believe me to be.

So with a heavy heart he urged Gringolet down the hill toward the stream, and as his guide had told him, followed it, looking always for the first glimpse of the Green Chapel on the opposite bank. Still he saw nothing but rode on through a deep ravine with jagged black rocks on either side that reared above him, shutting out the sun almost entirely. This is like the gateway to hell itself, thought Gawain.

As he came out of this dark ravine at last, the valley widened around him, sunlight falling on a grassy mound beyond the stream, which here ran fast and furious. But still he saw no chapel, green or otherwise. Not a bird sang. There were no flowers, and no snow either. The path looked treacherous ahead of him, so Gawain thought that here might be the best place to cross — for although the stream rushed and roared, he could see the pebbles beneath and so knew it could not be too deep. He spurred Gringolet through the stream and up onto the bank beyond. As he came closer and rode around it, he could see that the grassy mound looked like some kind of burial barrow, with dark gaping entrances on all sides, a place of death.

Gawain dismounted by a wide oak tree, and leaving Gringolet to rest and graze, he decided to explore farther on foot. This neither looks nor feels like any chapel I’ve seen before, he thought. It seems to me more like the Devil’s lair than God’s holy chapel. Yet it is green, and it is certainly sinister enough to suit the Green Knight.

Grasping his spear firmly, Gawain walked slowly around the barrow, searching for the Green Knight. He climbed right to the top so that he could see far and wide on all sides. Still he saw no one. But as he stood there, he began to hear from the far side of the stream the sound of grinding, like an ax being sharpened on a stone. Gawain knew at once it was the Green Knight. He fingered his green silk belt nervously, making sure it was tight around him, and as he did so a sudden fierce anger welled up in him and drove away his fear. “If the Green Knight thinks he can frighten me away,” Gawain said to himself, “then he had better think again. I may die today, but I’ll not die frightened. I won’t give him the satisfaction.”

He summoned up all his courage and called out loud, so loud that his voice could be heard over that incessant horrible rasping. “Gawain is here!” he cried. “Come out and show yourself. I am here as I promised I would be. But I won’t wait forever. Come out and do your worst.”

“I won’t be long,” came the booming voice that Gawain recognized only too well. “I think my ax needs to be a little bit sharper still — just in case you have a tough neck on you.” And the dreaded man, still hidden from Gawain’s sight somewhere in amongst the rocks beyond the stream, laughed till the hills echoed with it. But some moments later, the last of the grim grinding done, the Green Knight stepped out from a cleft in the rocks, fingering the blade of his ax and smiling a cruel smile.

He was just as Gawain remembered, except that incredibly, miraculously, his head was on his shoulders again. His hair and beard, green as before. His face and hands, green. And everything he wore was bright green too. He used his ax to vault the stream effortlessly and so crossed without even getting his feet wet, and then with huge strides, came up the hill toward Gawain, growing bigger and broader, it seemed, with every step, until this mountain of a man stood before him, his blood red eyes burning into his. Gawain had forgotten how terrifying those eyes were, but even so he managed to return the Green Knight’s gaze without wavering for a moment.

“You’re most welcome, Sir Gawain, to my chapel,” said the Green Knight, bowing low. “You’ve done well so far, very well. I said a year and a day from when we last met, and here you are. I said you would find me here at the Green Chapel, and you have. But that was the easy part. From now on you’ll find it a little more difficult, I think. Last time we met, if you remember, I said you could deal me any blow you liked. You showed me no mercy but struck my head from my shoulders. Now, as we both agreed and promised then, it is my turn. So get yourself ready. And don’t expect any mercy from me, either. I will give as good as I got from you.”

“That was the bargain we made,” Gawain replied, hiding as best he could the fear in his voice. “You don’t hear me complaining, do you?” So he laid aside his helmet and spear and shield. “I’m ready when you are,” he said. And clasping tight the silken belt to still his rising terror — for he knew its magic was all that stood now between him and certain death — Gawain went down on one knee before the Green Knight and gritted his teeth to await the blow.

Round and round and round whirled the ax just above Gawain’s head so that the terrible breath of it parted his hair as it passed by. “Bare your neck, Sir Gawain,” laughed the Green Knight. “I wouldn’t want to hurt a hair on your head.”

Gawain gathered his hair and bent his neck. “Get on with it, why don’t you?” he cried.

“With pleasure,” said the Green Knight. As the ax came down, slicing through the air, Gawain caught sight of it out of the corner of his eye and shrank from the blow. But the blow never came. At the very last moment, the Green Knight held back the blade so that it touched neither the skin nor a single hair on his neck.

“What’s the matter?” the Green Knight mocked. “The great Gawain is not frightened, is he? I haven’t even touched you, and yet you flinch like a coward. Did I flinch when you made to strike me a year ago? No, I did not. Yet you kneel there shaking like a leaf. Shame on you, Gawain. I had thought better of a Knight of the Round Table.”

Fuming now at these insults, and at his own weakness too, Gawain bent his head once more. “No more of your talk. This time I won’t flinch. You have my word on it.”

“We’ll see,” laughed the Green Knight. “We’ll see.” And once again he heaved up his ax high above his head. This time as the blade whistled down, Gawain did not move a muscle. He did not even twitch. But once more the Green Knight held back the blade at the very last moment. “Just practicing, Sir Gawain,” said the Green Knight, smiling down at him. “Just practicing.”

Now Gawain was blazing with anger. “Next time you’d better do it!” he cried. “It will be your last chance, I promise you. On my knighthood, I promise you that.”

“Nothing can save you this time, Sir Gawain,” said the Green Knight, wielding his ax. “Not even your precious knighthood will save your neck now.”

“Do your worst,” Gawain told him, resigned now to his fate. He closed his eyes and waited.

“As you wish,” said the Green Knight. “Here it comes, then.” He stood, legs apart, readying himself. Gripping his hideous ax, he lifted it high and brought it down with terrible force onto the nape of Gawain’s neck. This time the blade cut through the skin and the flesh beneath, but only a little, just enough to draw blood. No more. No deeper damage was done.

At the first sharp stab of pain and at the sight of his own blood on the ground, Gawain leaped at once to his feet and drew his sword. “One chance is all you get,” he cried. “I have kept my side of the bargain we made. If you come at me again, I shall defend myself to the death. Mighty though you are, you will feel the full fury of Gawain’s sword.”

Leaning now on his great ax, the Green Knight looked at Gawain and smiled down on him in open admiration. “Small you might be, Gawain,” he said, “but you have the heart and spirit of a lion. Put down your sword. We two have nothing to fight about. All I did, like you, was to keep the deal we made a year and a day ago. A blow for a blow, that was the pact between us. So let us consider the matter settled, shall we — all our debts to each other fully paid.”

Lowering his sword, Gawain put his hand to his neck and felt how small a cut it was. “I don’t understand,” he said, as bewildered now as he was relieved. “You could easily have cut off my head with one blow. Yet you took three, and then you just nicked me. I lopped yours off at one stroke back at King Arthur’s court. I showed you no mercy. Yet you spared my life. Why?”

The Green Knight stepped forward and offered Gawain his scarf to staunch his bleeding. “Think yourself back, Sir Gawain,” he began, “to the castle you have just left. Think yourself back to the Christmas game you played with the lord of that castle.”

“But how do you know about that?” Gawain asked.

“All in good time, Sir Gawain,” laughed the Green Knight. “All in good time. Three times you and he promised to exchange whatever it was you managed to come by. The first time you were as good as your word, as was the lord of the castle — a kiss in exchange for a deer, I believe it was. Am I right?” Gawain could only nod — he was too astonished to speak. “So that was why just now I teased you the first time with my ax, and did not even touch you. Then, the second day at the castle, you again did just what you had promised. What was it? Two kisses for a giant boar — and what a boar that was too! Not a great bargain for the lord of the castle, but an honest one, and that’s all that counts. Your neck is bleeding, my friend, because of what happened back at the castle on the third day. On that day, when the lord returned from his hunt and presented you with that cunning old fox, all you gave him in return, I seem to recall, were the three kisses you received from his beautiful wife. But you forgot to hand over to me the green silken belt she gave you, the enchanted belt that could save your life, the one you’re wearing now around your waist.”

Gawain gaped aghast at the Green Knight, understanding at that moment that somehow this Green Knight and the lord of the castle must be one and the same. Gawain flushed to the roots of his hair, knowing his deceit and cowardice were now exposed. The Green Knight spoke kindly, though. “Yes, Gawain, my friend, I’m afraid I am both the men you think I am. How that can be I shall explain later. It was I who wanted to play our little game. It was I who sent my wife to your room to tempt you, to test your honor and chivalry to the limit — and she did, did she not? In everything except the silken belt, you were as true and honorable as any knight that ever lived. Only the belt caught you out, for you hid it from me and did not hand it over as you should have done. You broke your word. For that one failure, I nicked your neck and drew blood when I struck for the third time.”

Gawain hung his head in shame now, unable to look the Green Knight in the eye. “Don’t judge yourself too harshly, my friend,” the Green Knight went on. “Three times you passed the temptation test and did not succumb to my wife’s charms, and that took some doing. You hid the secret of the green silken belt only to save your own life. It is no great shame to want to live, my friend.”

But Gawain tore off the silken belt and threw it to the ground. “How can I ever call myself a knight again after this?” he cried. “You and I both know the truth. I behaved like a coward. That’s all there is to it. Say what you like, but I have failed myself and betrayed the most sacred vows of my knighthood.”

Then the Green Knight laid his hand gently on Gawain’s shoulder to comfort him. “No man is perfect, dear friend,” he said. “But you are as near to it as I have ever met. You’ve paid your price — your neck’s still bleeding, isn’t it? And you’ve acknowledged your fault openly and honestly. Don’t be so hard on yourself. All we can do is learn from our mistakes, and that I know you’ll do.” He bent down then and picked up the silken belt.

“Take it, Gawain,” he said. “May it remind you whenever you wear it of what has happened here and back at my castle — both the pleasures and the pain.” Refusing to take no for an answer, he tied the belt around Gawain’s waist and stood back when it was done. “It suits you,” he laughed. “And my wife was right, too. You are a handsome devil if ever I saw one. Now, Gawain, my dear friend, come back home with me and we can feast again together and sit before the fire as we did before and talk long into the night. And don’t worry, this time my wife will behave herself, I can guarantee it.”

Tempted as he was by the warmth of the invitation, Gawain shook his head. “I cannot,” he said. “You know how much I should like to stay, but I must be on my way. If I come back with you I might never want to leave. No, I must go back to King Arthur, to Camelot, as quickly as I can. I’m sure they’ll be thinking the worst has happened to me.” He set his helmet on his head and made ready to leave, the Green Knight helping him into the saddle. “And thank you for the gift of this belt,” said Gawain as the two friends clasped hands for the last time. “It will always remind me of you and your lady, of all that has happened to me here, of the wonderful days I have spent with you this Christmastime. But it will also serve to remind me of my failures and my frailties. It will prevent me from ever coming to believe in my own myth. It will help me to know myself for what I am.”

“Go, then,” said the Green Knight sorrowfully. “Go, and may God speed you home. We shall miss you and long for your return.”

But settled now in his saddle, Gawain did not want to leave without a few answers. “There is still much that I’m puzzled about,” he said. “Who exactly are you? Which of you is you — if you know what I mean? Which is the real you? And who was the ancient craggy crone back at the castle who always watched me like a hawk? And tell me, how and why has all this happened to me?”

“After all you’ve been through, you have a right to know everything,” replied the Green Knight. “I am known in these parts as Bertilak of the High Desert. And the old lady you spoke of is Morgana le Fey, who learned her powerful magic from Merlin and uses it often to test the virtue of the Knights of the Round Table and to corrupt them if she can. She is jealous of Arthur. She always has been. It was she who enchanted me, made me into the green giant you see before you and sent me to Camelot a year and a day ago to discover whether the Knights of the Round Table are really as brave and chivalrous as they claim to be. How else, unless I was enchanted, could I have ridden off headless and later grown my head again? How else could I be the green giant? And what’s more, Gawain — and this will surprise you even more perhaps — that old woman is your aunt, King Arthur’s own half-sister. I sometimes think there’s nothing she likes more than causing King Arthur all the mayhem and mischief she can, and she can cause plenty. Still, so far, my friend, we’ve both survived all her machinations and her enchantments, haven’t we? I will lose my greenness between here and my castle, and you will survive to go home. All has ended well.”

There on that green barrow, the two knights parted and went their separate ways, the one riding to his castle nearby, the other setting out on the long journey back home to Camelot. It was long, too, and Gawain and Gringolet had a hard time of it. Hospitable houses were few and far between, so Gawain could never be sure of a warm bed and frequently found himself sleeping out in the open. The snow was often deep, and the paths precipitous and treacherous. But at least Gawain could be sure of the direction he was going, for the geese that had pointed his way to the lord’s castle before Christmas flew over him once again like an arrow, a singing arrowhead in the sky, this time showing him his way back to Camelot, back home. As for Gringolet, he stepped out strongly all the way, as any horse does when he knows he’s going home.