A massively profound and impactful idea has just hit me like a freight train. It’s early 2014. I’m visiting my parents, sitting with Mum watching a movie. But my mind is elsewhere. I’ve been thinking about the potential of these VR devices I’ve been playing with and of the emerging cloud services, which can provide data storage and supercomputing power when needed, along with other IT resources and applications such as advancing AI software.

My eyes start welling up. Not because of how mind-opening VR is, how game-changing cloud technology is or how powerful AI is. I’m feeling like this because I’ve just joined the dots and realised the weird thing I’m imagining is actually possible given today’s technology. Many of the most ambitious ideas can be made reality through the convergence of a number of our advancing fields, bringing them together like super-solution building blocks. I get Mum’s attention, mute the TV and try to explain what’s whirling around in my head, through tears and goosebumps.

‘I’m just thinking about how wonderful you are. How much, well, one day, when I have kids, I want them to know you how you are now. I want their kids and their grandkids and future generations in our family to know you. To know Dad. I’m just . . . thinking . . . there may be a way that these new things, new tech I’ve been looking into, could help make this happen. I mean . . . I think it might be possible to create something. It seems a bit ridiculous, but I know I could create a virtual copy of you. As you are . . . and I would want that for future generations. I . . . uh . . . I’m just not sure how I feel about it. I just want to talk it through.’

In her warm, calming voice, Mum says, ‘It’s okay. What do you mean a copy?’

‘I mean . . . Well, let’s think about it as if the technology existed when Grandpa was alive. You talk about him a lot. It’s always nice to hear – he seemed like such a great guy. You said I remind you of him?’ (My maternal grandfather Richard passed away just before I turned two. In our family albums there are photos of him holding me as a baby and putting his big hat on me, completely engulfing my head. Unfortunately, he passed away before the triplets were born.)

‘You do,’ Mum says, smiling. ‘I see my father in the way you walk. You have his smile and mannerisms . . . even . . . even your sense of humour.’ She starts laughing. ‘You stir the possum like he did. The way you sometimes irritate the triplets. So many things you do I just go, yep, that’s Dad.’

That makes me laugh too. It’s nice to know that I’ve taken on part of Grandpa’s personality. I pause again and find myself staring down as I gather these thoughts. ‘So. If this had existed then and I’d been able to create a virtual copy of Grandpa, I would want it. I’d love to be able to go into the virtual world and talk with him. See his face and his gestures and mannerisms, hear his voice and just . . . be there with him. It would be like a modern version of visiting someone’s grave and sharing stories with them. How would you feel if that were possible?’

Mum starts tearing up now. Responding is clearly very difficult for her. ‘I’m not sure how I feel about it. I think I would definitely want that for you and future generations in the family . . . to know Dad. But I wouldn’t want it for me. Because . . . I’d be reliving the loss over and over.’

For a moment I feel horrible for even coming up with this idea. It breaks my heart to see my mother upset. Then I remember something I’ve come to know all too well. That if we let fear get in the way, be it fear of failure, fear of how people may respond, or fear of not living up to the expectations we set ourselves, then we’ll never explore or discover anything. Instead, I believe we can take on board the thoughts of the people around us and incorporate their responses in planning and creation. Knowing that this particular design could provoke an adverse reaction means that I should approach the idea with caution. While the application of technology to create a digital avatar of my grandfather could have a negative – even traumatic – effect on Mum, it could also have a positive – even beautiful – effect on me, my siblings and future generations in our family. This is why we must approach all bold steps with respect and conscious design.

Conscious design. Yes, we must remain cognisant of the impact of what we create. But is the idea to preserve the memory of people alive today in this way even possible? I have no doubt it is. Cameras are advancing. So too are the algorithms that can do tricky things with camera footage. AI will come in useful for natural language processing, which can segment and figure out the words a subject is asking the digital avatar, while chatbot-style AI can recognise the intention behind the question and match it up with an answer from a database. Any form of extended-reality device could be utilised, either to bring the interactive avatar into the real world or to go into the virtual world and meet the avatar there. Finally, cloud connection, storage and processing will ensure the avatar is never lost and is updated with the latest advancements as they come, such as improvements in realism and interactivity. Yes, it is possible. We have the technology to create a virtual avatar of your living hero, or of someone who inspires you, or of your family members . . . or of you. How would this work? Does the avatar need to be directly controlled or can the conversations happen when the human counterpart is no longer around? Or can the avatar even keep learning for itself and go beyond what was originally captured?

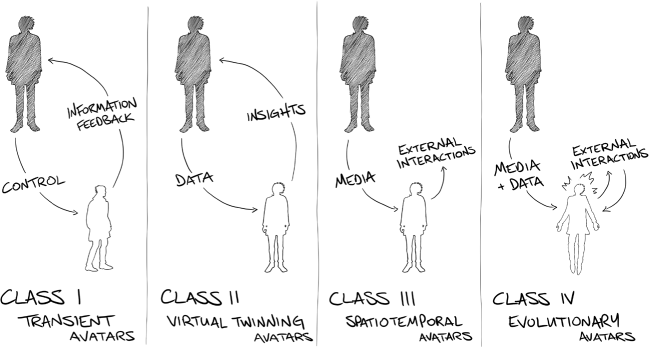

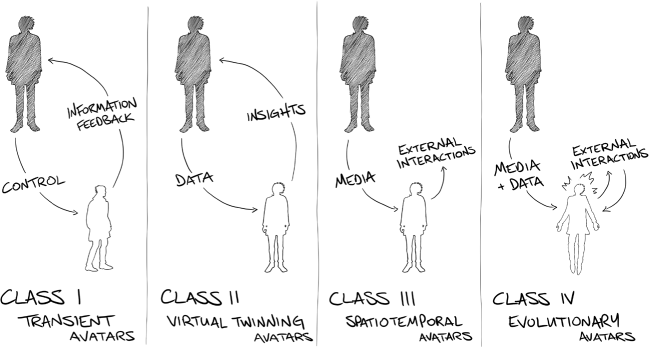

The dream would be to find if there is beauty in capturing an individual and allowing their friends and family to interact with them, even beyond death. Working through the various possibilities has led me to develop this simple framework for classifying our avatars, real or virtual, as they will become increasingly commonplace as we move into the future.

Those you can control (mostly in real-time), often temporarily, while playing video games, through robotic telepresence or through virtual experiences

A data representation of you, for purposes such as medical AI that can analyse, predict and improve your real health

A representation of you caught in space and time, for interactive, historical and memory-preserving purposes

A representation of you that continues to learn, develop, change and experience – facilitated by AI.

Figure 13: Four key avatar classes (AC-4)

For these, think of the films Avatar or Ready Player One, which both illustrate the ideas of real and digital telepresence avatars. In Avatar, the main character, Jake Sully – a paraplegic former marine – is supplied by the military with a controllable biological body through which he can port his mind. The film is set in the mid-twenty-second century on a habitable moon known as Pandora, in the Alpha Centauri star system. Jake’s larger avatar is modelled on a humanoid species indigenous to Pandora, the Na’vi.

Through telepresence technology you will be able to control your real-world avatar, which could be humanoid or android, may look like you or may not, eventually getting to the point where every movement and action you make is mirrored by your avatar counterpart – possibly with added or improved functionality compared to your biological body. Rudimentary versions have seen video calling to tablet PCs on a stick with wheels, allowing a person to be somewhat present in another place. Humanoid robots have been made for similar applications, such as remote telepresence control over robotic astronauts to carry out operations on the International Space Station. Robotic avatar telepresence has helped provide home-care assistance for elderly people, allowed kids who can’t make it to school to have a virtual presence in the classroom, and enabled people with high-level physical disability to work as waiters. Although not exactly commonplace yet, the technology quickly moves on, and new possibilities in human-like, controllable robotic avatars consistently emerge.

On the other hand, people are already controlling virtual avatars in games. Here, your avatar is a graphical representation of you, your alter ego or the character you’re controlling in the game. Through modern games, humans and virtual avatars are becoming more interconnected, allowing you to move, run, jump, look around and interact with objects and other avatars in increasingly natural ways. This is particularly the case when utilising extended-reality technologies, as in the VR depictions of Ready Player One. In the film, the main character controls his virtual avatar through natural actions with a range of external and wearable sensors, and even receives sensory feedback based on what his avatar experiences in the OASIS virtual world. Most times you go into VR, you control a virtual avatar of some form, which can be made to look like you or not. This is the interesting thing about avatars: they can be anything, look like anyone; they can be whatever you want them to be.

When it comes to creating copies of known people this class of avatar provides telepresence of the person, so they can be where they are not, acting through an avatar agent in the real or virtual world.

Avatars in this class are created as a digital, quantum (in the future) or other virtual representation of a person (or object or place, but let’s stick to people here) and fed data from their real-person counterpart for the system to analyse things about them (as previously discussed with respect to AI and health). It is in essence a virtual copy of you. Your virtual twin (currently, in a digital age, this is known as a digital twin) lives in computers and exists not as a collation of atoms, but as a collation of ones and zeros – and when the technology is widely accessible, you may have a quantum twin, which will be a representation of you in a quantum computer.

These computers, still in their infancy, will be much more powerful than current machines. They harness quantum bits, or qubits, which rely on the phenomena in quantum mechanics known as superposition and entanglement to perform computation. A qubit is somewhat analogous to the digital bit in classical computing, only it can be in a quantum state of 1 or 0, or be in superposition of both states, essentially being both 1 and 0 at the same time. I can’t do justice to the future implications of quantum computing here, so I’ll leave that discussion for another time.

For Class II avatars, whether the computing is digital or quantum, it’s all the same idea: you have a virtual twin of some form that exists as a Class II avatar, because it’s consistently fed data about you. The first two classes both require the real person for control or data flow, but if the person is not present behind the real-time flow of data into the avatar for control or analysis, then this leads us to Class III. And now we hit the classes that can continue to thrive in usefulness beyond the death of their real-person counterpart.

These basically allow us to capture a person in space and time. They can be made interactive, essentially being as much as possible of the person’s likeness – their looks, voice, gestures, mannerisms, personality, memories, interests – captured in an avatar representation with which we can interact in years to come. This is the space I find most intriguing and I quickly realised this was what I would have liked to explore had the relevant data from my grandpa been available (and similarly for my paternal grandparents). This can create beautiful, accurate and lifelike memories of an individual from the point in time the data was captured. In the realm of reality Class III avatars are most likely androids of people, like Android Phil previously mentioned. In the virtual realm these will be more like an advanced and interactive video recording, a new medium by which to learn about who a person was. Interactive playback of a virtual Class III avatar can be displayed in forms such as a video, giving a similar experience to a video call; VR, giving the feeling of going into a memory and completely immersive experiences (like those we’ll discuss in the next three chapters); and AR, bringing a perceived avatar hologram into the real world – you could even sit them on your couch and chat (just don’t expect them to drink any tea!).

These take all of the Class I–III technologies to a whole new level and allow the avatar of an individual to continue learning. This form of avatar isn’t reliant only upon data captured in time. Instead, AI allows the evolution of the entity to continue – drawing on new learnings, experiences and memories to simulate the person on which it was based, living on. But let’s be real, this is very Black Mirror (a sci-fi series that depicts extremely dark and disturbing potentials of technological advancement).

In my opinion, ethical considerations go into overdrive when Class IV avatars are being created. Firstly, even if they are possible, I can’t see too many good reasons for creating one. The avatar would evolve in a direction that is not necessarily, indeed is unlikely to be, the direction their human counterpart would have gone. With every choice we make, event we experience, interaction we have, we change – sometimes in a minor way, sometimes with large strides, but we do change. This means that from this very point in time you could go on to become one of an infinite number of possible versions of you, and this will remain true every time you read this sentence again. Internal thoughts, external stimuli, life events and a whirlwind of other stuff contribute to who you are and who you will become. Thus, creating a Class IV avatar of anyone seems a bit void of purpose, because it will never be a true representation of who that person would have gone on to become . . . only a single possible outcome from an infinite set of possible outcomes. So this is not something I choose to explore. That’s not to say we won’t see it happen. We likely will. But my happy realm is with virtual Class III spatiotemporal avatars and discovering the beauty within exploring those ‘captures’ of humans in space and time. And what an exciting realm it is.