It’s October 2017. I’m at a technology conference in Adelaide and finding myself staring a little while having a very casual conversation with Japanese engineering professor Hiroshi Ishiguro about his research. I ask him questions to keep him talking while I’m thinking about this intriguing yet somewhat eerie situation. See, just a few minutes ago I was standing in front of one of his androids, made in the image of him. A real android Class III avatar. It looked strikingly close to him too. Granted, the real professor doesn’t quite look 100 per cent human himself – with cosmetic surgery helping him meet his creation somewhere in the middle.

The android version, which speaks with the professor’s voice, is constructed using silicone rubber, pneumatic actuators and electronics, and features hair directly from the head of its creator. When not moving it can be quite deceiving. When the android does move to speak, my mind immediately picks up on the small details that aren’t quite right – the jagged head-turns compared to those of a human and the lack of human nuances like microfacial movements. The sheer engineering prowess that has gone into creating this robot should be applauded, and the convincing nature of it gives us a glimpse of a sci-fi Blade Runner Replicant-style future. Professor Ishiguro is a very interesting man who raises deeply philosophical and important conversations with his work. But why is it that we can find an android robot – one that in many respects looks deceptively human – well, a bit creepy?

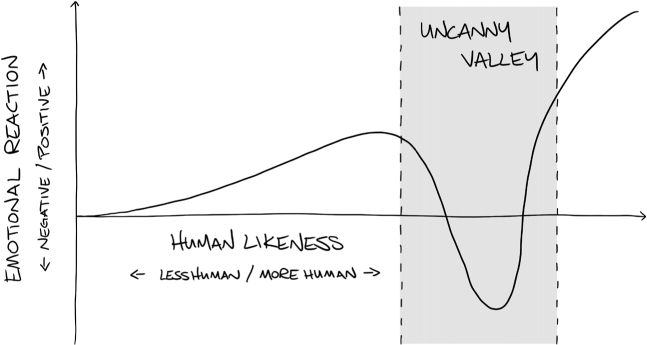

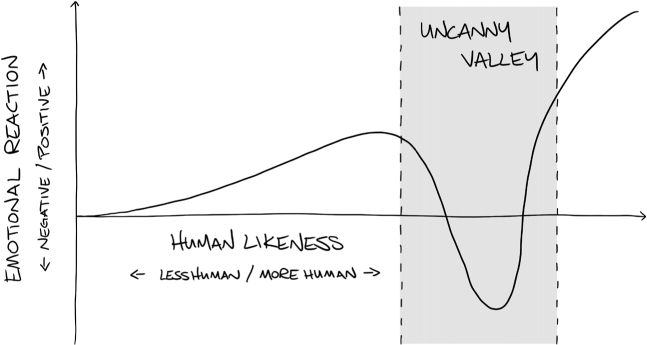

It’s due to a largely universal phenomenon in aesthetics known as the uncanny valley, which describes the relationship between human-likeness of an entity and our natural affinity (or not) for it. This helps us understand our response to a robot, animated character or avatar, depending where along the human-likeness scale they sit. It’s not an exact science but more an observable phenomenon. As an entity becomes more human-like, with such characteristics as mannerisms, voice and personality, we have a natural affinity for them. We like them more. But only up to a certain point. When the entity becomes too human, it’s common that our affinity plummets, our threat detectors go off and we can feel a little freaked out. It seems too creepy. This is the uncanny valley. The only way back out of the valley while moving in this direction of human-likeness is for the entity to be so human-like as to be practically indistinguishable from a real human. When we get to this point, people’s responses can be quite positive, even producing mirror neuron activity as if in the presence of another person.

My Virtual Jordan avatar could have been pretty creepy were it not for the realism, maybe only just emerging from the valley – though due to many stray pixels not quite finding their precise place in 3D space, he does look a little like he’s caught in a dust storm. Many animated movies have overcome the uncanny valley and learnt through experience. Shrek was the first computer-animated film to feature human characters in lead roles, so there were many unknown challenges in its creation. Shrek is an ogre character with numerous funny human qualities. He’s really quite likeable. In the first version of the film, however, his love interest, Princess Fiona, was created to be a beautiful and realistic human, with an array of advanced techniques (for the time) going into her realism. But she went too far along the curve in human likeness, becoming too real at times, yet not real enough, and plummeting down the valley. The disturbing nature of her ‘hyperrealism’ caused some children to cry when the film was previewed to test audiences, so the filmmakers reanimated her so that she was more cartoon-like and less like a human simulation, bringing her back along the curve and out of the uncanny valley.

The characters in WALL-E cracked the concept beautifully, with many of the little characters showing so much personality without being in any way mistakenly human – they owned their animated robot bodies but their likeability came from such qualities as WALL-E’s naïve, curious and empathetic personality and gestures; the love that blossoms between him and EVE; and the hilarious levels of frustration in M-O (Microbe-Obliterator), the small cleaning robot, every time he sees contaminants around.

In my show Meet the Avatars, I speak to Mike Seymour, an associate lecturer in the Business School at the University of Sydney, who also used to work in film digital FX. We talk about the uncanny valley and the idea that it may be possible for it to be ‘flooded’, so that it’s less about the appearance and more about the emotion. In other words, if we get to that part where a non-human entity unnerves people and falls down the valley, we can perhaps lift it out again by improving its emotions and human-like interaction. From what I’ve seen to date, emotional design plays a massive role, but the visual appearance and movement of created characters still elicit some of our strongest gut reactions.

To see more about this, I travel over to the University of Southern California in the US, where they experiment with a range of these ideas. First up, I get to sit with an avatar psychiatrist. She has been computer-generated rather than recorded from a real person, so she definitely looks animated. The persistent presence and seeming eye contact as she looks at me from the screen in front of me is surprisingly engaging. After my first few interactions she gets a few things jumbled up and doesn’t quite understand my responses. Maybe it’s my Aussie accent. It does break the engagement level a little.

The one I’ve been looking forward to is next. I head over to meet a Class III avatar of a real-life Holocaust survivor named Pinchas. I’ve heard that there’s a holographic display version of Pinchas to interact with, but walking into the room, all I can see is a large flat-screen TV turned sideways into portrait mode, with an idle repeating video of Pinchas sitting in a chair, just looking forward at me. Honestly, I was so looking forward to the holographic version that I’m taken aback. Surely this won’t give the feeling of Pinchas’ presence when I’m standing here looking at a 2D screen. Of course, I still give it a go, but my expectations of the experience have lowered.

Pinchas Gutter was born in 1932 in Łód´z, Poland. He has since been an educator and guest lecturer on the Holocaust. This project was set up as a collaboration between Heather Maio of Conscience Display at the University of Southern California’s Institute for Creative Technology and the university’s Shoah Foundation (established by Steven Spielberg). Pinchas was interviewed while sitting in a large high-tech dome (which I also got inside during this visit), where he was lit by 6000 LED lights and captured from 52 surrounding cameras for a total of 25 hours of recording over five days – answering more than 900 questions thrown his way. This all forms video that plays continuously, triggered by verbal interaction, and moving back to an idle state of Pinchas sitting and listening in between.

Before I know it, something magical happens. I pick up the microphone and say hello to Virtual Pinchas, to which he responds with: ‘Hello, I believe you have a question for me.’ I’m already stumped, because I don’t know much about his past other than that he is a Holocaust survivor.

‘Tell me about yourself,’ I begin with.

He proceeds to tell me a bit about his upbringing, where he was born and raised, mentioning his family with so much warmth. After telling me about a few more events, he mentions that he is a survivor of five concentration camps during the Holocaust.

‘Five?’ I didn’t know this. Already his story sounds unique. ‘Uh, tell me about the first concentration camp.’

Virtual Pinchas proceeds to tell me that when he was taken there with his family as a young man, the first thing that happened was his mother and sister were taken away from him. He never saw them again. He says that it is a very painful memory and mentions more events that occurred. Already it feels like my throat has caught. My mind is on the loss of his mother and sister. I want to go back and hear more about them.

‘Tell me about your mother,’ I say, to which he responds by describing her and how lovely she was. How he misses her. Already I’m getting lost in his story and I feel his presence, because in this interaction I am directing the conversation. That’s exactly what it feels like – a conversation.

I have quickly let go of the fact I’m speaking to a sideways TV screen. Rather, I am now immersed in getting to know this kind human who has been to hell and back. He is exposing vulnerability and sharing with me his life story and what he has been through. That is the power of immersion and the feeling of presence – the human side of technology.

He has just taken me on a journey through some terribly painful moments in his life. Yet he’s still so positive and warm. I now just want to give him a hug. This is definitely an effective mode of interacting with a person and getting to know them. It is confirming what I believed to be true, with a lower-tech solution than I thought was required – that a Class III virtual avatar can become a beautiful experience of human connection facilitated by technology. It can transcend time and space, immortalising one’s memory. It’s true that if done well, virtualising a person can be a wonderful thing.

Our near future will progressively see the utilisation of avatar technology in many aspects of life – from preservation of the memories of people like Pinchas to one-on-one communication with friends, loved ones, teachers and inspirational leaders; through virtual office meetings, training and surgeries; all the way to virtual assistants and even companions. It’s a space that will bring with it a huge range of ethical issues to work through, especially given the possible misuse of this technology. And this misuse has everything to do with the uncanny valley. If you get an avatar out of the valley to seem so human-like it’s basically indistinguishable from the real thing, this could be used to bring actors into movies who have already passed away. There have already been many attempts in films, using computer-generated imagery (CGI) and other filming tricks, such as when Grand Moff Tarkin, commander of the Death Star, was brought back through CGI in Star Wars: Rogue One – since the original actor, Peter Cushing, died in 1994. This may not have been the most convincing form of use, but as this technology advances, it will appear seamless in films. But there is a flip side.

A similar method of applying a person’s face to the body of another in video, known as deepfakes, could also be used to make a puppet of important people, such as world leaders, putting words in their mouth and creating fake video footage indistinguishable from real footage – something a friend Hao, who I met in this documentary, extensively researches. The approach utilises a deep learning type of AI known as generative adversarial networks to perform a range of analyses and processes (often involving one artificial neural network generating footage and attempting to trick another artificial neural network discriminating real from fake), ultimately producing results like overlaying footage of the subject’s face on the footage of an actor. This is in most cases done without the consent of the subject. These counterfeit videos will be something we need to be increasingly wary of and governments must address early. We need to treat video with the caution with which we already approach photos.

Governments and regulatory bodies will increasingly require scientists and technologists to advise on the many capabilities emerging from today’s advancements, and to keep up with those changes while shaping the direction they take. Reducing funding to science research is one of the greatest mistakes a nation can make. Uncertainty and change is on the rise in this new world. Propagating fear is not the solution. What allows us to thrive is sharing our humanity, positive visions, ideas and action so we can work towards a better world – one that fosters knowledge, love and connection across the globe. The need to recognise that with each new advancement there is always a positive opportunity is paramount. And that’s what we must imagine, must search for, address, understand, share and propagate.

For avatar technology, then, I want to explore the ideas that can enhance our nostalgia and human connection, and immortalise the memory of loved ones in as authentic a manner as possible. Taking my inspiration from wanting to have a virtual avatar of my own grandfather, I aim to locate some other grandparents who are willing to help me uncover what these innovations have to offer. For this adventure, I meet a caring and compassionate Italian couple. Both are fit and healthy. They’ve been together for more than half a century and have raised a large, loving family around them. Their names are Maureen and Michele.