‘Ex Africa semper aliquid novi.’ (Out of Africa, always something new.)

—Pliny the Elder, Roman scholar

Eating, whether at home or eating out, is most often a sociable and shared occasion. Among the Western and Westernised communities, who are mostly city dwellers, sharing a meal is done mostly in friendship, but it can also be in the interests of a good business relationship. However in the more traditional, rural, or tribal communities, the sharing of food characterises the spirit of the people and is a cultural tradition to be shared with strangers and possibly even enemies.

Because South African society as we know it now has grown through the centuries out of merging local cultures with those of various immigrant communities, the cuisine has grown out of a healthy and varied mixture of cultural ideas and flavours, tempered by what was locally available. The era of the ‘global village’ has also enabled an ever-widening array of foods to grace the tables of restaurants and the fast food joints across the country, making our cuisine as open to change and experimentation as is our new and progressing society.

Sometimes dishes or ingredients are not what they seem, not what you are accustomed to, but on many occasions they are simply hiding behind a different guise. You just have to dig a little deeper, or become accustomed to finding them with a different label or a different name. Some things will certainly be a totally new experience so try them with an open mind, or unbiased taste buds. You will certainly love some and no doubt you will loathe some too. It’s all part of the excitement of being a newcomer.

Traditional South African food in its various guises, is becoming ever more popular as we learn to appreciate our own styles and tastes and not always hanker over foreign fare. This is a well-developed trade in the wine lands and farmlands around Cape Town where locals and tourists alike enjoy a wide array of traditional cuisine, savoured from little taverns to top-end restaurants, as they drive through some of the country’s most idyllic rural scenery. Besides the Western Cape, top class restaurants and smaller bistros and pubs in all the major cities, and often some of the smaller villages, also offer a wide choice of local dishes.

Some of South Africa’s greatest traditional dishes come from the Cape Malay cuisine. In the 15th century, the Dutch brought Malays to work for them at the Cape during their many voyages to the East in their quest for control of the Spice Trade. The Malay women, who were excellent cooks, brought a vast knowledge of both oriental and Indian spices with them, then developed a culinary tradition based on the ingredients available to them in the Cape at that time. Refined over the centuries, these dishes are now considered great delicacies in many homes and are served in many restaurants as well.

There are some excellent and unusual Cape Malay dishes to look out for. Try one of the bredies for example. They resemble a vegetable and meat stew, but it’s the unusual additions that give them a mouth-watering edge. Some have a strong tomato base, others have quince, pumpkin or cabbage in them. And one of the most famous is called Waterblommetjie, a bredie made with the addition of a special water flower that grows wild in the ponds in rural areas in the Western Cape.

Bobotie is another hot favourite. Originally made from leftover mutton, it is a baked minced-meat dish that is deliciously spiced and usually also has some dried fruit added to it. Before being served, curled fresh bay or lemon leaves are poked into the top of the pie and then an unsweetened custard is poured into the holes made by the leaves, as well as over the rest of the surface.

Or you could try some of the more traditionally Malay fare: Pinangkerrie, a meat curry to which tamarind and fresh green leaves from an orange tree are added; or Denningvleis, meat flavoured with bay leaves and tamarind. Each dish has special accompaniments like sliced onion sprinkled with powdered chilli, fresh grated quince fruit mixed with chilli powder, a mixture of mint leaves, and powdered chilli moistened with vinegar. Sometimes a drink made of soured milk with a slice of orange is served with the curries. A variety of preserved fruits and other sweets may also be served.

Don’t be at all surprised to find many of the traditional Cape Malay dishes served with bright yellow rice. This is a local speciality, coloured and delicately flavoured with saffron or turmeric, and often has sultanas added for that tiny touch of sweetness quite common in this style of cooking.

There is an excellent book, part cookbook, but mostly a cultural culinary history of the early days of South Africa, and especially early Afrikaner cookery. It is called Leipoldt’s Food and Wine (Ed. T S Emslie and P L Murray. Cape Town, South Africa: Stonewall Books, 2004), and documents the culinary skills of C Louis Leipoldt who also wrote the old (and hence also part of our new) national anthem, as well as poetry, novels, prose and children’s books. In fact, he is seen as one of the greatest South African creative minds of the late 1800s.

The Malays also gave South Africa the heritage of wonderfully pungent and well-spiced sauces, chutneys and atchars (pickles). The chutneys and atchars are made with vegetables and fruit boiled and preserved in strong and spicy chilli, vinegar and sugar mixtures. Tangerine peel and pickled peaches are other delicacies. These are frequently served as condiments or side dishes.

Much of the rest of the cuisine in South Africa is based on an amalgam of European influences: French, British, Flemish, German, Italian, Portuguese, Greek and others. Pasta dishes are a firm favourite in many homes. A large Portuguese immigrant population has meant that the likes of a ‘prego roll’ (similar to a steak sandwich, but encased in a crispy Portuguese-style bread roll) is quite common fare, especially as a pub snack.

But today, with the global trend in fusion cuisine, it is often hard to pinpoint any specific cuisine in many restaurants. More often you will find a glorious mixture of tastes and styles blended to suite the climate, season and whim of the chef.

Indian and Chinese food, although they have not become as mixed into the local cuisine as European food has, are eaten with relish by all, especially in restaurants and also at home in those communities.

Many South Africans prepare curry dishes in their homes, with the assistance of some excellent local Indian cookbooks like Indian Delights edited by Zuleikha Mayat, and Ramola Parbhoo’s Indian Cookery for South Africa. In the Indian markets—in Durban they are by far the best— there is an abundance of exotic spices and curry mixtures to buy for your home cooking. One of the most notable of these, at least by name, is ‘Mother-in-law Exterminator’ which gives an indication of the potency of much of the Indian food in South Africa. Nearly all the exotic spices and herbs are also available in speciality shops in the main centres. Quite a few are even found on supermarket shelves now.

Chinese food is more often eaten in restaurants, but this cuisine too is becoming more mainstream as some of the larger supermarkets carry a good range of ingredients—and even pre-packaged fast-food varieties too. Although the Chinese population is fairly small with its heart in Johannesburg—the city centre and the suburb of Sydenham—there is an enclave of supermarkets and shops that stock a wonderful array of dried or canned imported Chinese delicacies: from dried shrimps to water chestnuts, umpteen varieties of soy sauce...and much, much more. An endless array of noodles is also stocked.

Some of the very indigenous dishes may well be a touch out of your ambit, as they are for many Westernised South Africans. But the adventurous could do a trial run on morog, a local version of spinach and not totally unlike its European cousin; or sorghum porridge for breakfast, in place of cereal, which is quite delicious with milk and sugar. For the very adventurous, you could try mopani worms, which are dried and eaten as snacks (like biltong), or added to rural African type stews. But along with flying ants, they are not obligatory and very unlikely to crop up in your food circuit unless you purposefully seek them out!

Quite a delicious snack found at the end of the summer and in early winter is a fairly dry mealie on the cob, which is roasted over an open brazier. Fairly dry, chewy and crispy, this is one of my favourite snacks and is usually sold in the downtown city areas, near the bus and train stations and the taxi ranks.

In the main cities, the bigger and better supermarkets as well as the delicatessens and speciality food stores carry a fairly good array of foreign food. But you will have to curb your desires a little as anything imported usually carries a higher price-tag. This is partly because of the novelty value, but mainly because you are paying for the pleasure of it being transported all the way to South Africa.

But be consoled with the fact that because this is a culturally diverse community and has been for many years, there are a number of things made in South Africa, but modelled on foreign foods. Any number of neo-European cheeses, for example, are made here and many are of high quality, and a pretty good imitation too! If you are hooked on the Australian spread ‘Vegemite’, you will find a South African substitute called ‘Marmite’ (vegetarian) and ‘Bovril’ (meat extract), both of which are just like their namesakes in England. A lot of the international food conglomerates manufacture in South Africa and you will probably be surprised at how many Western-style and Western brand-named ingredients are available here.

Many of the health food shops stock the unusual goodies you may need for your own special brand of home cooking: pine nuts (ensure they are fresh!), carob powder (cocoa substitute for chocolate flavouring), buckwheat, tofu, tahini paste and a wide variety of vegetarian foods are available. They may also stock unusual cheeses, goat’s milk and natural yoghurts, as will some of the speciality food stores. In reality, there are very few ingredients you cannot get here, but it may take a while to source them.

The amount, variety and quality of organic produce is growing fast—and the more there is a demand for it, the more this sector will expand we hope! Most often you will find organic foods in health food stores, but certainly some of the larger supermarket chains, Woolworths in particular, carry a good range, especially of fresh produce.

A South African supermarket shopping quirk to remember is that we pay for plastic shopping bags. The reason for this is ecological: to try and prevent people littering the environment (plastic shopping bags are often referred to as our ‘national flower’!) we are encouraged to reuse them as often as possible, or better still not use them at all, but rather take your own bags with you.

There has always been an abundance of seafood in South Africa’s coastal waters. Because of the icy west coast seas and the markedly warmer Mozambican current on the east coast, the variety of seafood is also extensive. Unfortunately today, like most parts of the world’s oceans, many of our favourite fish species are dwindling so fast they are close to becoming endangered.

In the days of yore, due to the hot and sunny climate, preservation of fish was of prime importance. Pickling was popular, especially with pepper, chillies, ginger, coriander seeds, caraway, aniseed and cumin being favourite pickling spices. Today, the tradition of pickled fish is carefully followed to gourmet delight! And as a dead giveaway to my culinary abilities, I have to admit that some excellent canned varieties are found in most supermarkets!

Snoek, a type of cod found in the Cape seas, is very popular today and often sold smoked. It is great to eat cold on sandwiches and often served at picnics, or as an excellent side-dish at lunch or on a buffet spread.

Some of the other top deep-sea fish are really good, especially when served fresh (never having been frozen). Some local names to remember are Kabbeljou, Cape Salmon (no resemblance to Scottish Salmon), Yellow Tail and even hake. However, like in much of the rest of the world’s oceans, fish stocks are being seriously depleted here too. For this reason the World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF) in South Africa has drawn up a list of which fish are ‘no-no’, ‘maybe’ or ‘definitely okay’ to eat from a sustainability perspective. (See http://www.wwf.org.za/sassi)

Shellfish is also easy to get here, although some of the frozen fare is certainly imported from across the globe, not that it detracts from its quality or flavour. Prawns, crayfish, mussels, oysters and clams are seafood favourites and descendants of the French Mauritians, now owners of some of the sugar cane plantations on the KwaZulu-Natal coast, have added their Creole touch to these dishes. The South African Portuguese with some input from their Mozambican relatives seemed to have made prawns their trademark, and you may often see dishes called ‘LM prawns’ or ‘Piri-Piri prawns’ on the menu—delicious but beware of the fire in the piri-piri chilli.

Although many of the major cities are not coastal, this does not prevent landlubbers from getting very high quality fresh and frozen fish. Demand is so high, especially in Johannesburg, that some of the coastal dwellers complain that inlanders probably get some of their best catches, popped on a plane and rushed to the restaurant tables and supermarket shelves, almost quicker than they do.

Most South Africans like to eat meat and the country certainly does have a reputation for producing good quality beef, and the mutton or lamb from the Karoo region is also said to be extremely good. In fact, many people just do not consider a meal complete without a meat dish. Chicken, mutton, fish (more recently) and pork (to a much lesser extent), follow hot on the heels of beef on most shopping lists.

Venison, that is game meat from antelope and warthogs (similar to wild boar), is a winter favourite, probably because this is the hunting season. However, there are now also a number of commercial farmers farming these animals as well as game birds to supply the city markets throughout the year, so you certainly will be able to get venison out of season, but not quite as readily. Certain restaurants specialise in ‘wild’ cuisine and have some of the more exotic ones on offer most of the time—try a steak of crocodile, a slice of warthog, or guinea fowl stew if traditional venison is not exotic enough for you.

Ostrich meat which also falls into the ‘wild’ category is now more easily available, even from some supermarkets these days. The ostrich industry, which in the period leading up to the first World War was a major money spinner from feathers for women’s high fashion, took a depressing dive as war broke out and fashion changed. But today, the ostrich farmers are smiling again as meat—very low fat so it’s very healthy—from this large bird makes it on to ever more dining tables.

Biltong, this strange local delicacy, originated in the 1830s when the Trekboers (the forerunners of the Voortrekkers) decided to explore the interior of the country and needed to preserve as much meat as they could from the game they shot. This snack has endured ever since with some spicy updates. It is made from strips of meat, very often game, but now also frequently beef, which has been marinated in spices and salt and then dried in the wind and sun. It is often served as a snack with drinks, but more and more restaurants serving traditional fare are using it in salads and as a topping for some of their dishes. Try it—you may be surprised how easily you take to it. It is easily available from both speciality biltong stores as well as in supermarkets, and also frequently found in the convenience stores attached to roadside petrol stations.

Other specialities, born of necessity by the explorers, are rough breads and meat dishes which are baked in an outside clay oven, fairly similar to those used in some Arab countries to bake bread.

Cooked green maize, a local version of corn-on-the-cob, is still a favourite even among city-slickers. If in the mid- to late-summer you hear a high-pitched shriek as you quietly go about your business in your residential neighbourhood, don’t be alarmed. It quite often is, what seems to me, the unintelligible call of the green mealie sellers. Their wares are worth investigating, as they are usually freshly picked in the rural areas and make a delicious easy addition to a meal. Just boil until tender and serve with butter, salt and pepper. A microwave oven shortcuts this process to a matter of three or four minutes!

Maize is called mealie in South Africa and refers to the cob and its pips, or to the plant actually growing in the fields. Maize meal is called mealie meal and is a coarse-ground maize flour. In its cooked form, called putu or pap locally, this is the staple starch of many Africans in this country, in fact much of the southern African region—like rice is in China—and is also a firm favourite with many others, especially at a barbecue or braaivleis. It is cooked either to be like a thick porridge, or often made a little more dry and served with meat or gravy dished rather as mashed potato is in some cuisines. Corn flour is a fine white powder made from ground dried mealie and used as a thickening agent in sauces, desserts and the likes.

Very good quality fruit and vegetables are grown in South Africa and a large variety is available in the supermarkets and greengrocers, but prices can be quite high, especially when something is not in season. An increasing quantity of fresh produce is exported these days, sometimes leaving those of us who live here with second best. But you can always find what you need, it just means a harder search or a higher price tag at times.

Some of the more exotic Eastern fruits like starfruit or rambutans are quite new to these shores, but entrepreneurs are starting to grow them as certain areas in the country are well suited to sub-tropical fruit production. Mangoes, guavas, papayas, paw-paws (similar to a papaya), avocados and bananas have a long traditional on these shores, as do pineapples, watermelons and a wide variety of citrus fruits. Deciduous fruits are mostly grown in the Western Cape with apples, peaches, nectarines, plums, apricots and the like easily available and of high quality when in season. Lychees and Cape gooseberries are other more unusual favourites. The berry family—raspberries, blueberries, strawberries and blackberries—were a rare luxury some years back, but ever more are being grown here and some are now imported too. A large, fresh fruit-juice industry has grown up in South Africa, with many au naturel juices (with no added sugar, colour or preservatives) competing for your attention on the supermarket shelf.

In recent times, the small fruit and vegetable producers have become disenchanted with the monopolistic approach of many of the large chain stores and supermarkets. Consequently, a host of vegetable and fruit stalls and farmers’ cooperatives have sprung up on the outskirts of the cities and bigger towns, as well as along some of the trunk roads. Although not quite as convenient as the store just down the road, prices are often much more reasonable as the middleman has been cut out and freshness is usually assured.

There are also a number of small farmers on the perimeters of the larger cities who grow fresh herbs of excellent quality. And if you are lucky enough to have a home with a garden, growing your own can be fun and very a rewarding addition to your dishes.

Typical Local Dishes and Delicacies

Boerwors: local sausage

Boerwors: local sausage

Biltong: dried meat

Biltong: dried meat

Butternut squash soup: made from a deep yellow butternut squash, very slightly sweet, thick and creamy

Butternut squash soup: made from a deep yellow butternut squash, very slightly sweet, thick and creamy

Sosaties: skewers of meat often interspersed with dried fruit or vegetables

Sosaties: skewers of meat often interspersed with dried fruit or vegetables

Boboti: minced meat dish with Malay spices and egg topping

Boboti: minced meat dish with Malay spices and egg topping

Potjiekos: meat stew cooked with lots of vegetables and spices in a three-legged pot on an open fire

Potjiekos: meat stew cooked with lots of vegetables and spices in a three-legged pot on an open fire

Rooibos tea: indigenous plant used as an alternative to regular tea. Caffeine-free and has many alleged health properties

Rooibos tea: indigenous plant used as an alternative to regular tea. Caffeine-free and has many alleged health properties

Marula Jelly: made from the fruit of an indigenous tree, it is a sweet accompaniment for venison and sometimes game birds.

Marula Jelly: made from the fruit of an indigenous tree, it is a sweet accompaniment for venison and sometimes game birds.

Koeksisters: traditional Afrikaans fare made from plaited dough which is deep fried and immediately dropped into icy-cold sweet syrup. The dough absorbs vast amounts of the syrup and the result is a crunchy, very sticky dessert—ideal for the very sweet-toothed!

Koeksisters: traditional Afrikaans fare made from plaited dough which is deep fried and immediately dropped into icy-cold sweet syrup. The dough absorbs vast amounts of the syrup and the result is a crunchy, very sticky dessert—ideal for the very sweet-toothed!

Don’t expect inexpensive food in South Africa just because of our sunny skies, an abundance of agricultural land and a strong farming tradition. Sadly, the cost of food—even of staples like bread, maize meal, milk, meat, fruit and vegetables—is fairly high, especially top quality produce which is only a little less expensive than in Europe. Strangely, eating in restaurants, which, although costly to most locals, is not anywhere near as high as, say, London or Paris.

Restaurant dining is certainly a large factor in the general socialising and entertaining process in South Africa, obviously more so in the larger towns and big cities. This is partly because more city slickers have a bigger disposable income, and partly because there are many and varied restaurants to choose from—but of course one feeds the other. Add a dose of high tourism potential like Cape Town and you have an even greater number of restaurants with a vast variety of cuisines.

For almost all restaurants in South Africa the etiquette is very dependent on the type of establishment. The more casual and easy going restaurants—and this does not necessarily mean a lower cuisine quality—require less formality in dress and style beyond the normal requirements of polite behaviour. Raucous children (or for that matter childish adults) are not particularly favoured in these middle- to upper-end places, although they would certainly not exempt children who are well behaved.

Where to Go

Fine Dining

Johannesburg: Auberge Michel; Linger Longer; Restaurant La Belle Terrasse and Loggia

Johannesburg: Auberge Michel; Linger Longer; Restaurant La Belle Terrasse and Loggia

Cape Town: Bosman’s; Cape Colony; The Atlantic

Cape Town: Bosman’s; Cape Colony; The Atlantic

Casually Excellent

Johannesburg: Gramadoelas; Moyo; 74; Koi; Browns; La Cucina di Ciro; Thomas Maxwell Kitchen

Johannesburg: Gramadoelas; Moyo; 74; Koi; Browns; La Cucina di Ciro; Thomas Maxwell Kitchen

Cape Town: Wakame; Constantia Uitsig; Five Flies; The Africa Café; Aubergine

Cape Town: Wakame; Constantia Uitsig; Five Flies; The Africa Café; Aubergine

Durban: Jam restaurant (in Quarters on Avondale); Wodka Restaurant

Durban: Jam restaurant (in Quarters on Avondale); Wodka Restaurant

Easier On The Pocket, Easy On Style

Johannesburg: Franco’s Pizzeria and Trattoria; Lucky Bean

Johannesburg: Franco’s Pizzeria and Trattoria; Lucky Bean

Cape Town: Willoughby and Co; Olympia Café and Deli

Cape Town: Willoughby and Co; Olympia Café and Deli

Durban: Nourish; Billy the Bums; Bean Bag Bohemia

Durban: Nourish; Billy the Bums; Bean Bag Bohemia

To celebrate a very special occasion, or to treat yourself to some of the finest dining around, South Africa has a fair number of excellent top-class restaurants to choose from. Cape Town and Johannesburg have the greatest number of good dining places simply because they both have a big cosmopolitan population, while Cape Town also attracts a high number of top-end tourists, and Johannesburg is host to most international business transactions.

Ambience, style and cuisine are very individual, but in general they follow a Western European tradition in terms of etiquette, dress code and general behaviour, and on occasion may even be slightly less formal in manner, although style and service is usually out of the top draw. No particular no-no’s apply bar the normal need for low-key, quiet and refined behaviour, and of course small children too young to appreciate either the good conversation or the highbrow cuisine of your dinner would probably not be very welcome.

Tips on Eating Out

Remember

Booking is always a good idea for any restaurant that you have been told is popular, or currently trendy, and booking is essential for Friday and Saturday nights;

Booking is always a good idea for any restaurant that you have been told is popular, or currently trendy, and booking is essential for Friday and Saturday nights;

Some restaurants close on Mondays, some on Sundays and some are not always open for lunch. It is always good to check this out in advance if you have your heart set on a time and place since there is no regular rule of thumb. Of course, there are some open seven days a week for lunch and dinner;

Some restaurants close on Mondays, some on Sundays and some are not always open for lunch. It is always good to check this out in advance if you have your heart set on a time and place since there is no regular rule of thumb. Of course, there are some open seven days a week for lunch and dinner;

In most restaurants you can dine fairly early, from about 6:30 pm onwards, but mostly kitchens tend to close between 10 pm and 10:30 pm. This doesn’t mean you have to be out by then, but that you need to have placed your order by then. Some kitchens are open later on Friday and Saturday nights, but don’t bank on it! Lunch is generally served from about noon to 2:30 pm or 3 pm.

In most restaurants you can dine fairly early, from about 6:30 pm onwards, but mostly kitchens tend to close between 10 pm and 10:30 pm. This doesn’t mean you have to be out by then, but that you need to have placed your order by then. Some kitchens are open later on Friday and Saturday nights, but don’t bank on it! Lunch is generally served from about noon to 2:30 pm or 3 pm.

Tiny Tots

For those with boisterous tiny tots, there certainly are easy-to-manage places and some that really make a big effort to cater to little children. An example in Johannesburg is Mike’s Kitchen, and nationwide, most of the chain eateries, such as Spur steakhouses or Nando’s, are easy on the kids and on the pocket.

For those with boisterous tiny tots, there certainly are easy-to-manage places and some that really make a big effort to cater to little children. An example in Johannesburg is Mike’s Kitchen, and nationwide, most of the chain eateries, such as Spur steakhouses or Nando’s, are easy on the kids and on the pocket.

Tipping

It is not obligatory in South Africa but almost all diners do tip at least 10 per cent, and more if the service and attitude of the staff is good or excellent. It is worth noting that the salaries of waiting staff are very low as restaurateurs tend to expect them to make much of their income from tips. I certainly always tip generously in restaurants and coffee bars, and should I have the misfortune of really bad service I will certainly not tip at all, but I will also make it quite clear why I am not doing so to ensure it is understood that bad service is not acceptable at all.

It is not obligatory in South Africa but almost all diners do tip at least 10 per cent, and more if the service and attitude of the staff is good or excellent. It is worth noting that the salaries of waiting staff are very low as restaurateurs tend to expect them to make much of their income from tips. I certainly always tip generously in restaurants and coffee bars, and should I have the misfortune of really bad service I will certainly not tip at all, but I will also make it quite clear why I am not doing so to ensure it is understood that bad service is not acceptable at all.

Décor is generally traditional and conservative, if very tasteful, and in some establishments you can certainly expect the full gamut of silver cutlery, fine bone china and crystal glassware, with staff trained in the nuances of serving in a refined dining environment. Dress is always smart casual and you can dress up as much as you like, but anything less than smart trousers and a jacket for men and elegant evening wear for women—dress, or a skirt or pants paired with an elegant evening jacket—is not acceptable. Ties are not usually required these days and shorts of course are a no-no!

To experience this level of sophistication and service you can certainly try Auberge Michel in Sandton, Johannesburg. Established by Frenchman Michel Morand and top Johannesburg businessman Vusi Sithole, it serves superior French cuisine in a relaxed atmosphere with top quality service. It also has an extensive wine cellar. And if you are interested in local South African politics and business, there is every chance you will catch a glimpse of many a famous person too. Another Johannesburg stalwart in the top league is Linger Longer, also in Sandton, which has beautiful grounds and a long history of fine dining. Food is a combination of classic French fare with a touch of the East. The Westcliff Hotel has one of the most superb views in all of Johannesburg, which adds ambience to the top quality of its fine dining restaurant, Restaurant La Belle Terrasse and Loggia.

Cape Town and the surrounding wine lands also has its fair share of fine dining restaurants. One of the most impressive is Bosman’s Restaurant, part of Le Grand Roche hotel in the Drakenstein valley at Paarl, some 45 minutes outside Cape Town. The setting is superb in the heart of the wine lands with dramatic views of the nearby mountains. The food is a fusion of imagination and innovation and the wine cellar is excellent. (It is Africa’s only Relais Gourmand restaurant). You can dine on the patio in good weather, and for a table of eight or more they will help you choose a menu to suit your tastes. The Le Grand Roche heritage began in 1717, and the current buildings were restored to their original Cape Dutch splendour in the 1990s and have now been declared a national monument.

You can also try the Cape Colony Restaurant in the world-famous Mount Nelson Hotel which offers fine dining with impeccable service and a traditionally elegant décor. The menu on the other hand has the best of contemporary local cuisine with a touch of Asia to add spice. The wine list is also very good. Another fine dining restaurant to try is the Atlantic Restaurant in the Bay Hotel, which has superb views of Table Mountain and specialises in South African and Asian cuisine.

Generally, you can get almost any regular alcoholic drink in a South African bottle store. There is a huge variety of local beers and wines, and a great many imported ones too. Almost any form of spirits is available—some of the more standard spirits are made locally, while the top end is generally imported from the country of origin. There is a big range of brandy, many of which are locally made and very good. Nearly all whiskies are imported; while the other usual spirits like gins, vodkas, rums and such are both imported and locally produced. Of course not all bottle stores stock all products, but with a bit of research your every choice is sure to be covered.

There is also a local speciality called ‘cane’—the name is derived from the fact that it is a sugar cane distillate—and frankly, it has very little taste. It is not the most sophisticated of drinks, but adds an alcoholic kick to any mixer. You’ll hear people yell, “Ji’me (give me) a glass of cane an’ coke!”, which means, “May I have a glass of cane spirits and Coca Cola”.

A number of other weird and wonderful local concoctions are also available, which are based on a simple alcohol like cane mixed with flavours like the marula tree fruit, or pineapple perhaps, or even strawberry or mango. These drinks are definitely for less sophisticated palates, but quite good fun. Beware of the morning-after headaches, though!

Talking of headaches and hangovers, beware if you are offered mampoer or witblitz, the latter meaning ‘white lightning’! These are home brews, similar to European schnapps, and are famed in some of the rural farming areas. Illegally brewed, they contain very high levels of alcohol and need to be drunk with caution by the uninitiated. Locals seem to be able to quaff them with great abandon and love nothing better than for you to join them at it. You will fall over long before they do. You have been warned!

Indigenous African beer, made from sorghum and called maheu (pronounced ‘ma-he-oo’), is a fairly thick drink, sometimes even like very runny porridge, quite sour, and very much an acquired taste. However if you do learn to like it, it has a fairly high nutritional value and a low alcohol content.

Farm workers enjoying some traditional beer, maheu, after a hard day’s work.

The real home-brewed thing is most often found in the African rural areas and drunk in great quantities at special feasts and traditional ceremonies. Beer consumption often forms part of the ritual at a ceremony like a tribal marriage, a courtship or a funeral.

Sorghum beer is also made commercially for consumption in the urban areas. They are packaged in glazed cardboard cartons, rather like milk cartons, and are sold almost solely in the townships. In the 1976 riots that flared across South Africa’s black urban areas, angry students burned the state-owned beer halls in protest, not against the beer, but against the fact that so many people spent so much money there and it was all for the state’s coffers.

Drinking ‘clear beer’—the kind most of you will know as normal beer—is a national pastime among almost all South Africans. No social function—braaivleis, sports match (live or on TV), or party—is thought complete without the consumption of vast quantities of Lion or Castle, Hansa or Millers. South African Breweries (SAB) is the producer of the whole toot, and until recently, they have been a very successful near monopoly.

However, with the quest for a little more individualism, a few small breweries have sprung up around the country, sometimes selling their beer only in their own locality. Many of these beers are of excellent quality and often worth the extra cost. But do a taste test yourself across the board. If nothing else, you will have a lot of fun and endear yourself to local drinkers with your superficial knowledge of the brews which can be shared during those endless discussions about sport—any sport.

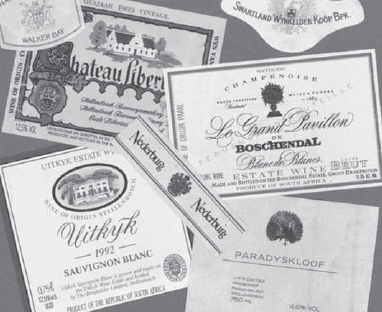

Although the early Dutch settlers may have brought the first vines to the Cape, the French Huguenots brought viticulture to the southern shores of South Africa, and an extensive and internationally acclaimed wine industry developed and flourished over the years. Some stalwart brand names to help you negotiate the copious racks in the bottle stores until you have a handle on the subject are: Boschendal, L’Ormarins, Nederberg, Backsberg, Thelema, Hamilton Russel, Meerlust and Groot Constantia. Of course there are many, many more, but these will be a good guide to begin with.

In the wine-growing area of the south-western Cape, not far into the hinterland from Cape Town, you can visit a number of the country’s best wine estates on what is called the ‘Wine Route’. You can drive from one to another tasting the wares and, when you find what you like, you can buy it directly from the estate. Although you won’t effect a huge price saving compared to some of the larger bottle stores, you certainly will have a wonderful time. You may even discover a small hidden-away estate that suites your taste buds and your pocket, and does not sell its products through the larger retail outlets.

Some South African wine labels, showing the diversity available.

Many of the estates are hundreds of years old and the traditional Cape Dutch architecture is unique and often set against idyllic, mountainous backdrops. Some estates offer wonderful lunchtime spreads which gives you a chance to sample the local cuisine with the fruits of the vine. For the more popular ones, like Boschendal, it is advisable to book ahead of time. As the day wears on, beware, the wallet gets progressively lighter along with your head, while the crates of wine weigh heavily on the axles of your car.

Check the Cape Town tourist information outlets or website (http://www.capetown.gov.za) for information on the Wine Route: which estates are open to the public, the opening times, what is on offer, and the likes. There are also some excellent pocket books written by wine buffs to help guide your choice of wines without you having to make too many costly mistakes. My favourite is the highly informative South African Wines by John Platter, which is updated each year with information on all the new vintages and is ideal for anyone who wants to make the most of South Africa’s long wine tradition and especially the small, new and not commonly known boutique wineries. There is also one called The Plonk Drinkers Guide, which rates the cheaper wines by price as well as quality. These books will also explain the meaning of the blue, red and/or green bands around the neck of the bottle.

The Biodiversity & Wine Initiative (BWI), found at website: http://www.bwi.co.za, is an organisation which promotes organic and eco-friendly wine farming. They can alert you to which wines are farmed and produced in this manner.

It is good to remember that some restaurants have a full liquor licence which means they can sell any alcohol, while others only have a wine and malt licence which means you are restricted to beer, wine and the odd liqueur only. There are still a few restaurants that do not have a licence at all, so you bring your own drinks. This lack of licence does not necessarily denote a lack of quality in a restaurant, it just means they have not been able to get a liquor licence or do not want one. For the customer, as long as you are familiar with this quirk, it means you can drink exactly what you choose because you bring it along, and at half the price! As with restaurants the world over, drinks, especially wine, have a pretty high mark-up.

Although many licensed restaurants will frown rather long and hard at you, you are allowed to take your own alcohol into any restaurant you like. They are, however, allowed to charge you a corkage fee, for letting you drink it there. It is not an unforgivable thing to do, but it honestly doesn’t win the friendship of the proprietor. I think the most appropriate time to bring your own wine to a licensed restaurant is when you have been there before and have found the wine list inadequate or of bad quality.

A lot of entertaining is done at home and most of it is pretty casual—in fact, South Africans are not very formal people in general. It is quite common to have people round for dinner or even a casual supper during the week, but it is most often done over the weekends. It is also fairly standard to offer to bring something: either a dish of food, or a salad, or (less complicated for a newcomer) some beer and/or wine. Often your host will tell you not to worry about bringing anything. It is then up to you to gauge the situation, to see if it is really meant or not. Except in the most pretentious homes, a bottle of wine or a box of chocolates is always welcome.

Dress for home entertaining is usually casual too. Men will be fine in decent jeans, chinos or other casual trousers and an open-neck shirt. Much the same goes for women. There is no harm at all in asking your host how you should dress, rather than arrive in a dress suit and find everyone else around the pool in swimsuits!

Don’t be too casual in manner, however. Slouching on someone’s lounge suite (unless you are really good friends) or prying into the private rooms will not be welcomed, unless you are invited to view a new possession or to have a look around the house, in which case your host will no doubt show you around. And don’t take your pets to visit your friends! Most people have pets: and animals rarely get on with your friends’ four-legged friends.

The braaivleis, literally meaning ‘roasted meat’, is a barbecue—a distinct cultural occurrence, which has spread from being mostly part of white South African culture to being pretty ubiquitous in one form or another. Usually shortened to the word braai, it is one of the most favoured ways of outdoor entertaining, and is also one of the easiest and most relaxed. And it’s very much a family affair—kids are always welcome.

If you are invited for a braai, here’s the ritual: it’s always outdoors, and around the pool if your host has one. It could be for lunch which means you arrive at about noon and expect to eat an hour or so later. Then the afternoon is usually spent chatting. If it is a dinnertime braai, you arrive in the early evening for a night-time affair. Of course when a braai is going well, lunchtime can stretch right through to suppertime and beyond. Vast quantities of beer are usually consumed, wine too.

The spread includes a variety of meat, fish (on occasion), a range of salads, bread rolls and special sauces. Sosaties, a traditional favourite, consists of little blocks of marinated meat sometimes interspersed with pieces of onion, green peppers (capsicum) and other vegetables on a skewer, similar to a kebab. Another favourite is boerewors or ‘farmers’ sausage’, which is a South African-style sausage, not too refined and often spiced with many ‘secret’ ingredients. Sometimes home-made boerewors is served, but often they are bought from good butcheries and supermarkets.

If it’s a very traditional braai, you will have mieliepap or stywepap, also called putu (described earlier), which is a type of stiff, fairly dry porridge made out of maize (a little like Italian polenta). Mieliepap is often an acquired taste for newcomers. Often, guests chip in by bringing a salad or a dessert, or perhaps some beer or wine. When you are invited, ask your host what you should bring along.

Early on at a braai, you may find all the men in a huddle and the women forming their own social group. It’s the men’s role to cook the meat to perfection—probably the only time many South African men can be persuaded to do anything remotely domestic, so leave them to stand around the fire, always with a can of beer in their hand, discussing both the merits of cooking methods and the day’s sporting events. Once the meat is ready everyone tucks in and a grand time is had by all.