Chapter 2

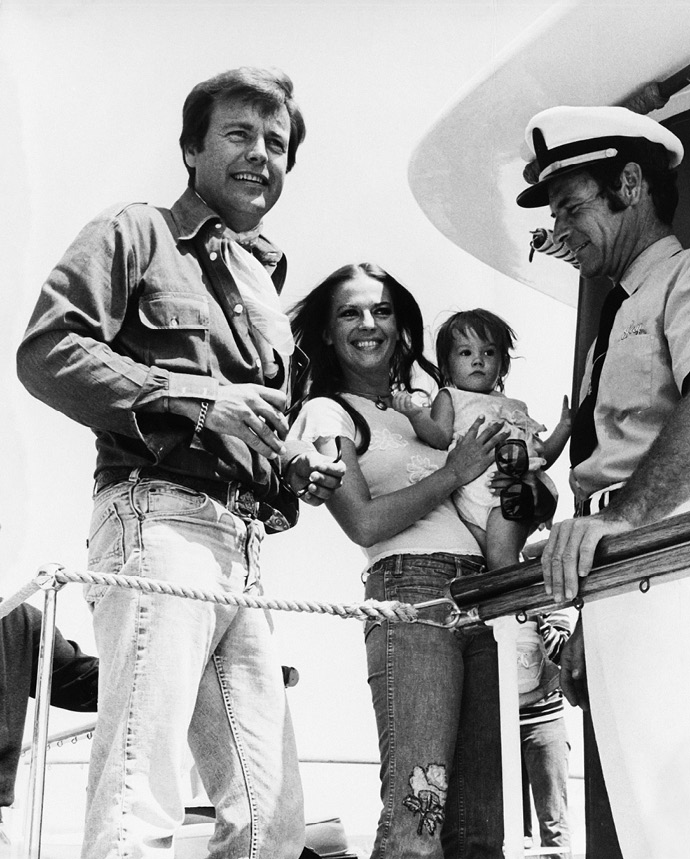

R.J. and Natalie, with baby Natasha, on the Ramblin’ Rose, on their second wedding day, July 16, 1972.

In the early spring of 1974, life was blooming anew. Roses and gardenias were budding in our Palm Springs backyard, our dog Penny gave birth to a litter of puppies, and my mom went away to the hospital and emerged with a baby.

There’s a home movie of me kissing her pregnant belly, so I’m sure my mom must have explained her pregnancy to me, but I was too young to understand and I don’t have any memories of that time. What I do vividly recall is the shock of suddenly seeing my mom arrive at our house in Palm Springs in an ambulance.

I was allowed to climb up into the ambulance to see her. She was resting on a stretcher and clutching a tiny swaddled bundle close to her chest.

“Natooshie, this is your new sister, Courtney, and she’s brought you a present,” my mother announced. I liked presents, but I was suspicious. What was the catch? I unwrapped the package tied up with a ribbon. Inside was a pretty new doll.

“Would you like to hold Courtney?” Mommie asked in a lullaby voice. “She looks so much like you!”

I peeked into the fuzzy blanketed bundle and saw a little sleeping face that looked more like Daddy Wagner to me. Who is this person in my mother’s arms? I’m supposed to be the only one in my mother’s arms!

I hoped we could work out a bargain. Could I keep my doll but send the baby back?

It soon dawned on me that, unlike Penny’s puppies—which we gave away to good homes—Courtney was here to stay.

Now that my parents had two children, they decided to move back to town and settle down in Beverly Hills. We rented a house there while my mom shot the comedy Peeper with Michael Caine, and then a place in Malibu, before moving into a house on North Canon Drive. My stepsister Katie—Daddy Wagner’s daughter from his prior marriage who was six years older than me—lived nearby with her mother and so could easily come to visit us.

Our new white Cape Cod–style two-story house was in the heart of Beverly Hills. Designed by the architect Gerard Colcord, it had dark blue shutters framing the windows and a tall sycamore tree shading the wide, flat front yard with its low picket fence. In the back was an oval pool with turquoise tile. Boughs of bright pink bougainvillea dangled over potted pansies, geraniums, and hibiscus flowers. In the fall, the lemons would ripen from green to yellow on our lemon tree. Bees, butterflies, and hummingbirds hovered year-round.

The house itself was large but not showy. My mom was very involved in the decor. Decorating was not just her favorite hobby; she even ran her own freelance interior design business for a few years—Natalie Wood Interiors—decorating houses for her clients, who were mainly her friends. My mother loved to make statements with bold patterns and colors, particularly her favorite, blue. There was floral-patterned wallpaper covering nearly every wall: blue laurel wallpaper in my parents’ bedroom, a pink-and-green rose pattern in my bedroom, and a motif of red, green, orange, and purple lilies in the hallway. It was as if she wanted to bring her favorite season, spring, inside. She loved when everything was blooming in the garden, and would often be outside, cutting roses and her favorite fragrant white gardenias to arrange in silver vases around the house.

I remember fireplaces in almost every room, with a picturesque, hand-carved marble fireplace in my parents’ bedroom. Heavy dark wood pieces sat alongside wicker furniture and big, upholstered chairs and sofas. Photos of family and friends in silver frames dotted shelves and long tables; on the walls hung framed Chinese needlepoint and works of art. Everything had a connection to someone famous or admired, or to a relative or friend. A Marcel Vertès painting of a ballerina hung in the living room, given to my parents by Jack Warner, my mom’s boss back in her Warner Bros. contract days. Our long travertine coffee table had once been owned by Marion Davies. She had been a famous movie star my dad remembered fondly from his childhood. The word that comes to mind when I think of this time is “bountiful.”

For my mother, having children was a do-over, a chance to raise us in a way she wished she had been raised, to give her daughters the childhood that she had missed. My mother had been working as a professional actress since she was six. She was a wunderkind, balancing her acting work with public appearances, school, ballet, piano lessons, Girl Scouts, and horseback riding. She was also the breadwinner for her family, supporting her parents and her sisters from a very young age. She didn’t stop working her entire childhood. She couldn’t. The prosperity of her family depended on it.

“I never got to have a real childhood,” she used to say, her voice sounding a little sad. “I grew up on studio soundstages.” Or, “I learned how to decorate my home from the sets on my movies.” She used to say she could concentrate on schoolwork only when someone was banging a hammer because she was so accustomed to studying on noisy, bustling movie sets.

The childhood she created for us at the house on Canon Drive was very different. Our home was alive with animals and close friends and family, yet our bedtimes were enforced, we went to regular school, and we kept regular hours. Dinner was on the table at six, and no ifs, ands, or buts, we took showers every night. Above all, we were given time to play and to simply be young, roaming the gardens, lost in our games.

As well as dogs, we had cats, guinea pigs, mice, and birds we kept in shiny cages in the small kitchen adjacent to our playroom. The animals were always having babies, and so then there would be puppies, kittens, and baby guinea pigs as well as tiny mice that appeared one morning in the mouse cage after the mommy mouse escaped and somehow located a daddy mouse. My mother was a true animal lover. She often favored the ugly ones, like the small black Labrador–Jack Russell mix with rotten teeth and bad breath that she adopted from Dr. Shipp’s Animal Hospital. We called him “Siggy,” but his full name was Sigmund, after Freud himself. “I’m naming him Sigmund Freud,” my mom joked, “because everybody needs a good shrink in the house.”

She had a special way of communing with animals. When one of our cats, Maggie or Louise, would saunter by, I would grab at them, holding them awkwardly. They would inevitably wriggle out of my arms, leaving a small scratch or two as they pulled away from my grasp. My mother seemed to know how to pick them up so they were soothed and still, rocking them like babies and talking to them in her most delicate voice. The cats would relax immediately, folding themselves into her embrace, purring contentedly. “How does she do that?” I asked myself.

One day she was in the playroom holding Courtney’s white cockatiel on her finger. I had friends over and we were sitting quietly on the floor, marveling at how the bird stayed there, perched on her extended finger as if drawn to her magnetically. “Hello, beautiful bird,” she cooed in a voice as light as air, stroking the bird gently as we all watched, enraptured. Out of nowhere, our black-and-white cat, Maggie, swooped into the room, leaped toward my mom’s hand, and ate the cockatiel in one swallow! A few white feathers in the air were all that remained. We were completely stunned. My mom’s expression was a cross between wonder, shock, and respect for Maggie’s feline abilities. “R.J.!” she called. “Maggie the cat just ate Courtney’s bird!” My friends and I sat openmouthed, not knowing whether to cry or laugh.

My mother was stricter than people might imagine a movie-star parent would be with her daughters. Our home atmosphere was casual, but always within the parameters of certain expectations. We knew we had to be polite at all times, be respectful, be well turned out, and stick to the schedule. At home we were not allowed to eat sugary cereals for breakfast or to play when we had homework to do. Our TV watching was monitored. We were taught to always say “please” and “thank you,” and to send thank-you notes for every gift we received. Back then I thought my mother was overly bossy. There was one recurring verbal exchange we had more than any other.

“How come I always have to do what you tell me?”

“Well, I’m the mommy,” she would say. “When you’re the mommy, you can make the rules, but I’m the mommy now, so I get to make the rules.”

That always put an end to the conversation.

Being well groomed and looking our best was also considered important. On special occasions, Courtney and I would be taken to buy velvet or lace dresses from a children’s boutique in Beverly Hills, and Mommie curled our hair with her hot rollers. I remember standing in her bathroom as she put the big, heavy plastic rollers in our straight, baby-fine hair, expertly securing them with long, silver pins. Once we had five or six rollers in our hair we were free to play for ten or fifteen minutes. Inevitably, one or two would slide out and we’d return to my mom’s bathroom so she could put the roller back on the warming stick and redo the curl.

During these early years of my childhood, my mother worked very little as an actress and mostly stayed home with us. By the time she became pregnant with me, she was thirty-two years old and had been working steadily as an actress for twenty-six years, paying her dues and making her eligible for her pension. Although she took on a couple of projects after I was born, she made a conscious choice to spend time simply raising her family.

In the hot summer months we splashed in the pool, playing Marco Polo, having swim races, and diving for objects at the bottom, my dad shirtless in his swim trunks, golden chains dangling around his neck, my mom wearing a block-printed Indian dress over her bathing suit, her hair in two pigtails, usually held together with colorful elastic pom-poms. She’d sit on a lounge chair and watch my dad and Katie dive off the diving board or do backflips into the pool. Or she’d be in and out of the shallow end with me and Courtney, water wings firmly wrapped around our skinny arms, guiding and encouraging us through the water. At lunchtime, the kids ate grilled cheese sandwiches or bowls of Campbell’s cream of celery soup sitting on the warm redbrick ground while our parents and their friends lunched nearby under the shady sycamores.

Soon after Courtney was born, my parents hired a woman named Willie Mae Worthen to cook for us. Mommie and Daddy Wagner were great at many things, but cooking was not one of them. Their idea of food preparation was snacking on shredded wheat or All-Bran cereal with raw sugar and half-and-half on top, making BLT sandwiches, or heating up their favorite canned soups. My dad’s specialty was something called “Salisbury corn skillet,” which was basically beef patties with canned corn on top. Willie Mae was from Atlanta, Georgia, and she made us succotash, chicken potpie, sweet potatoes, and green beans. When my British dad came to visit, he taught her how to make my favorite shepherd’s pie; she made it her own by adding corn and Worcestershire sauce. Willie Mae was tall and lean, with the softest skin and biggest laugh—rivaling even my mom’s. We fell for her so completely that my mom asked her to be our nanny and she soon became a beloved fixture in our family. When my Russian grandmother first met Willie Mae, she unwittingly rechristened her by mispronouncing her name “Vilka Maka” with her thick Russian accent. Katie, who was nine at the time, morphed her Russian pronunciation into “Kilky,” and somehow it stuck. To Courtney, Katie, my parents, and me, Willie Mae was known as Kilky.

Even though we had Kilky to help take care of us, my mother was the one who drove me to my new preschool, the Sunshine Nursery School, in Brentwood. I was almost four by then, but once again, I hated being away from my mom; I missed her so acutely, with such a sharp pang, that I could barely make it through a minute before the tears would well up and I’d start crying. My mother consulted her therapist, who told her to give me something of hers so I could hold on to it while she was away. She decided to give me her Cartier Panthère watch, if you can believe it. When it was time for her to leave, she put the beautiful watch in my hand, looked me straight in the eye, and told me, “Natasha, I promise I will be back to pick you up when the big hand is on the twelve and the little hand is on the twelve.” Her voice was strong and direct and let me know that we were in this thing together. I held on to her watch for a week or so before I was ready to spend those few hours at preschool without her.

Another time, she made a deal with me. “If you can stay at school the whole day without crying once, I’ll buy you a present.”

She asked what I wanted.

“I want a blue talking dog,” was my response. She couldn’t quite make this happen, but she came awfully close, buying me a stuffed dog that talked when I pulled its string to reward my next tear-free school day.

Once, I fell off the jungle gym at preschool and cut a gash just above my eyelid. I remember hitting the ground—boom—my mouth full of dirt, then warm liquid trailing down my face that tasted like metal. When I saw the adults around me looking nervous, I started to cry. The school called my parents, who rushed me to a doctor. My next memory is of both my parents standing over me in a doctor’s office, each holding one arm. I see my dad looking at me and then looking at my mom. His gaze is steady and his eyes are telling her, “Stay calm, Natalie, Natasha needs you to keep it together, Natasha is going to be fine, keep it together, Nat.” She keeps it together while the doctor takes the gleaming needle out and sews up the skin above my eyelid, pulling the thread through and through. I am awake but sort of lulled; my mom is awake but not at all calm. If she cries, I cry, if she panics, I panic. I remember receiving a clear message: my happiness is her happiness. If I’m sad, she’s sad. The world is dangerous, especially if Mommie isn’t there. If she’s here, I’m safe.

At age five, I started kindergarten at the Curtis School. Both my mom and I were worried about how this separation would go. Luckily I locked eyes with another skinny little five-year-old named Tracey, and we soon became inseparable. She was my surrogate safety blanket when my mom left. Just a glimpse of her blond curls and grin let me know I was going to be okay.

Meanwhile, my sister Courtney was quickly growing from a swaddled baby into a small blond bulldozer. When she was three, she wore a T-shirt with “Here Comes Trouble” printed across the chest. I felt this was an accurate description. Later we became incredibly close, but in those days, she seemed hell-bent on destroying everything that was mine. If I were quietly playing with Barbie dolls in my bedroom, she barged in without knocking, breaking all the furniture in Barbie’s DreamHouse before rolling out again. Though she was more than three years younger than me, she was the bully and I was her victim. I lived in fear of her. Her favorite means of domination was hair pulling. Her fingers were like the jaws of a pit bull. “Oooow! Mommie! Kilky! Courtney’s pulling my hair!”

At the sound of my cries, Kilky came running. She was physically stronger than my mom, so it was usually her job to pry Courtney’s hand open. In my sister’s palm would be a clump of my hair. “Courtney,” Kilky would say in a serious tone of voice, “you leave Tasha alone.” Sometimes my mom would gently intervene. “Courtney, sweet pea, come with me. I want to show you something in my bedroom.…”

It got to the point where, whenever I saw my sister coming, I’d yell, “Get out of my room! Get out now or I’m going to tell!” Before Mommie or Kilky could get there, Courtney had already bitten the nose off my beloved stuffed snoopy, Jennifer, or kicked my wooden dollhouse to the floor.

My stepsister Katie posed a different kind of problem. With her strawberry-blond hair cut into a shag and freckles across her fair skin, Katie seemed exotic, untouchable to me. She was older and lived with her mom and two brothers in an apartment and dressed like a boy in rock T-shirts and bell-bottoms, while I was always in dresses. To her, I was a mama’s girl, a Goody Two-shoes, something of a Beverly Hills princess. As with Courtney, I would later grow to love her completely. But back then, I think I saw Katie as more Courtney’s sister than mine. They shared the same father by birth, whereas Katie and I were not technically blood relatives. While I stuck close to my mom, Katie stuck close to her father and Courtney. She took it upon herself to act as Courtney’s protector, always siding with her in arguments and making me feel outnumbered. My mother took her role as stepmother to Katie very seriously. She went with Katie to her very first appointment with the gynecologist, they shopped together to pick out furniture for her room at our house, she let Katie drive her little Mercedes when Katie first got her driver’s license. Despite our different biological mothers and fathers, my mother made sure her three daughters knew that we were a family.

My parents had this saying, “I love you more than love.” To me it meant they loved each other more than any other parents loved each other. But I think what they meant by it was that the way they felt about each other was bigger than any word they could come up with. They had started saying it when they first started seeing each other, and they continued to say it for the rest of their time together. They engraved the words on silver frames, gold jewelry, just about anything they gave to each other.

When my dad wasn’t calling her “darling,” he called my mom “Nat” or sometimes “Nathan.” He loved to make her laugh with his impressions of Cary Grant, James Cagney, and other classic movie stars. My mom also made him laugh—sometimes with her sharp wit, sometimes because she had her not-so-sharp moments. We used to have this crazy dog named Winnie who once chewed up all the grass in one section of our yard. My dad called the landscaping company and hired them to lay down new grass, then we all went out of town for the weekend, but not before he had sequestered Winnie so he couldn’t get near it. When we got home, we went in the backyard and saw that Winnie had been on the rampage again.

“That goddamn dog,” my dad shouted. “He broke loose and tore up the new grass!”

“But, R.J., this is a really smart dog,” my mom said, a note of wonder in her voice. “Look. He chewed the grass in perfect squares.”

“No, Natalie,” Daddy pointed out. “The gardeners laid the grass in squares!”

Whenever he had to patiently explain an obvious fact to her, he called her “Natalie.”

If I wanted a favor from my mom, I had a unique method that usually worked. I would take a whole grapefruit (her favorite) and stick a toothpick in it with a piece of paper attached that would read something like, “Can my friend Jessica spend the night, please? You are beautiful.” Or “You are the best actress in the world.” I would wait upstairs for her to come into the entryway, then I would roll the grapefruit down the stairs, where it would land with a thud at her feet.

“What’s this?”

Jessica and I would watch from the top of the stairs as she picked up the grapefruit and read the message aloud. Then she and my dad, consummate actors that they were, would pretend to deliberate.

“Can Jessica spend the night? Well, I don’t know. R.J., what do you think?”

“I don’t know,” my dad would muse. “Jessica, do you really want to spend the night?”

“Yes, I do!” Jessica would say earnestly.

Finally, my mom would give in. “Okay. Let me talk to Jessica’s mom.”

One year, our nanny Kilky gave Courtney and me two fuzzy little ducklings as an Easter present and our parents let us keep them. Once the baby ducks started growing, one of them became a very mean drake we had inappropriately named Sunshine. Sunshine was quarantined off to the side of our garden, where an abandoned wooden playhouse stood next to a small pond. Meanwhile, the other duck started flying around our neighborhood, making the rounds like it owned the place. My mom would get phone calls from surrounding houses. “Um, Mrs. Wagner, your duck is in our pool.” She’d hang up the phone and shout, “R.J., the duck is in the neighbor’s pool again! What are we going to do?” Then she and my dad would crack up laughing. They thought it was hilarious that there was this duck flapping around in fancy people’s yards and pooping in their pools, all those Beverly Hills housewives opening their drapes in the morning and screaming, “There’s the Wagners’ duck again!”

Finally, my mom called a family meeting.

“Girls, we’re going to have to get rid of the ducks.”

Courtney and I screamed, “Nooooo!”

“Well, they can’t just fly into other people’s pools!”

My dad piped up with, “Well, why can’t they?”

My mom pondered this for a moment, and then echoed my dad. “Well, why can’t they?”

So we kept the ducks for a little longer until they wore out their welcome for good. One morning, Courtney and I decided to revisit our old playhouse by the duck pond. But this was Sunshine’s turf now, and he did not welcome our visit. He cornered Courtney, hissing at her in a loud, scary screech. Courtney let out a series of bloodcurdling screams as I ran to get help. My mom, who had been applying a facial mask in her bathroom, heard the kerfuffle and raced down the stairs like a flash of lightning, her face slathered with bright blue clay. I shot into the house toward my mom so fast that we collided with each other like Laurel and Hardy. My mother, Kilky, and I stumbled over one another to get to the playhouse, slipping in the mud from a recent rainfall. Kilky and my mom rescued Courtney from Sunshine, getting covered with brown muck in the process. It was sheer mayhem. “That is it!” my mom decided with finality. “We are getting rid of these ducks!” Sunshine and his sister were swiftly donated to the Malibu wetlands that same afternoon.

After we moved to Canon Drive, Daddy Gregson, who had been living in England, rented an apartment in Malibu where he would stay when he was in town. I loved when he came over to visit or to take me out, greeting me with his posh British accent—“Hello, dahling, it’s so good to see you!”—and grinning widely, with his silver hair and eyes that crinkled like raisins. He and my mom sat at the bar chatting, trading stories about the business, updating each other on common friends, discussing my progress, my schedule, my life. They respected and liked each other. My American dad and my British dad always seemed genuinely happy to see each other as well. There was an ease to their conversations and a respect for their differences as well as a shared understanding that they had both loved the same woman and they both loved the same child.

Most times, Daddy Gregson took me to Hamburger Hamlet on Sunset and Doheny, where I ordered the number eleven (a bacon cheeseburger) and a strawberry milkshake. Sometimes he took me to backyard barbecues or family parties given by his friends. Other times he bought me a present. There was a toy store a few blocks from our house, but my excitement over his suggestion “Let’s go to the toy shop” was always dampened by his insistence that we walk there. Walk? On foot? “No one walks,” I explained to him with a sigh. “Why can’t we drive?” Being English, he never understood why we couldn’t walk there, and being American, I never understood why we couldn’t go by car.

As a child, I thought the story of how my mom met and married my two dads was perfectly unremarkable. Only later did I realize how extraordinary it was that my mom had met and married my Daddy Wagner, divorced him, then met my Daddy Gregson and had me, and then happily remarried Daddy Wagner.

Robert John Wagner, aka R.J., had been my mother’s childhood movie crush. My mother loved to tell the story of the first time she saw him. It was 1948, and she was ten years old and under contract at 20th Century-Fox. She was walking down a hallway with my grandmother when she saw R.J. walking toward her. He had dark brown hair, bright blue eyes, and golden skin. He was eighteen years old and under contract at Fox as well. As he brushed by her in the studio hallway, he didn’t look back, but my mom did. In that instant, my mother turned to her mother and whispered, “When I grow up, I’m going to marry that man.” For the next seven years, when she saw Robert Wagner, it was only in movies. Then, when she was seventeen and he was twenty-four, they met again at a fashion show at the Beverly Wilshire Hotel, where a photographer snapped pictures of them together. A few weeks later, R.J. called and asked for a date. On July 20, 1956, my mom’s eighteenth birthday, he took her to a screening of his movie The Mountain with Spencer Tracy. In the morning, he sent my mother yellow roses and a note promising to see her again. She found him handsome and kindhearted, with a great sense of humor. They kept their relationship secret from the press at first, meeting at quiet restaurants, off the beaten track. Their romance was youthful and tender. “R came over with a pair of yellow pajamas as a gift for me because I had been in bed all day sick with the flu,” my mother wrote in her journal from the time, “what a dear heart.”

R.J. was older than my mother, seemingly secure in himself. He’d learned his self-assurance the hard way. R.J.’s father, a Detroit steel executive, disapproved of him becoming an actor, wanting him to follow him into the family business. But R.J. had been determined, carving out a career for himself in Hollywood. He first came to public attention in the 1952 movie With a Song in My Heart, in which he played a shell-shocked soldier, and after that, he began to win leading-man roles. In 1954, he appeared in Prince Valiant, the adventure film that made him a star. Like Natalie, he understood what it meant to live with the glare of flashbulbs wherever you went. When they met, they realized they both felt lonely and isolated in their families—and by life in the spotlight. Now that they were together, the loneliness disappeared. They both wanted the same things in life, to have a family and to give their children the kind of pure, unconditional love that they hadn’t always received from their own families.

In October 1957, my mother went upstate to shoot scenes for her movie Marjorie Morningstar, alongside Gene Kelly. R.J. went with her, staying for the three-week shoot. Both my grandparents adored R.J.; they thought he was kind, handsome, and talented and approved of the relationship.

After my parents returned in December, R.J. took my mother out for a champagne supper. My mother spotted something shining at the bottom of the champagne glass. It was a diamond-and-pearl ring. The inscription on it read: “Marry me.” She said yes. In order to escape the press, my parents ran away to Scottsdale, Arizona, to get married, and invited only their closest friends. The wedding date was December 28, 1957. They traveled by train and checked into their hotel under fake names. The night before the wedding, my dad wrote my mom a note.

“Darling, I miss you. Are you going to be busy around 1 p.m. tomorrow? Love you, Harold.”

My mom wrote back: “I won’t be busy. How about getting married? All my love, Lucille.”

On their wedding day, my mother wore a white cocktail dress with a lace hood instead of a veil and long white gloves, a bouquet of calla lilies in her hands. My dad wore a dark suit, a sprig of lilies of the valley in his lapel. In a home movie of the events, my parents can be seen walking past a building, posing for pictures, and getting on a train to leave for their honeymoon.

My mother was not yet twenty years old. Her new husband was twenty-eight. They agreed to put their plans to start a family on hold for a couple of years, realizing they weren’t old enough for that responsibility just yet. R.J. not only loved my mother but respected her enough to support her career—something not many men did for their wives in the 1950s. Immediately after they married, she refused to take a part in the film The Devil’s Disciple with Burt Lancaster. Under the studio contract system, she simply had to show up for work. It didn’t matter if the part, the director, or the script was to her liking. Her contract stated that she had to do it anyway. But after fifteen years in the business, she’d had enough. After she said no to the Lancaster film, Warner Bros., her studio, placed her on suspension. My grandmother pleaded with her to go back to work. But R.J. bolstered my mother’s confidence and encouraged her to stand up for herself. With his support, she remained on strike at Warner Bros. for eighteen months—and it worked. In February 1959, Warner announced a new agreement between the studio and Natalie Wood. Not only had she been given a raise, but she would also be allowed to make one film a year of her own choosing, outside of the studio.

By then my parents had bought their own place, on North Beverly Drive, and my mom set about renovating it. It was going to be opulent, with marble flooring, crystal chandeliers, and a giant marble bathtub upstairs adjacent to their bedroom. While work on the house continued, my parents costarred in their first film together, the drama All the Fine Young Cannibals, in which R.J. played a jazz trumpeter in a tortured relationship with the character played by my mother. But the film was not a critical or box office success, and after the failure, both my parents were looking for a hit.

My mother found it in the form of Elia Kazan’s Splendor in the Grass, a powerful 1961 drama in which she starred as Deanie Loomis, a young woman from a middle-class Midwestern family. Warren Beatty played her boyfriend, Bud, in his first leading film role. The part required my mother’s character to undergo an emotional breakdown, culminating in a suicide attempt, with Deanie trying to drown herself in a reservoir. My mom was working on one of the most professionally fulfilling projects of her career. At the same time, R.J.’s career experienced a downslide. Fox decided not to renew his contract, and he was out of work.

In the chaos, they fought. They had been married barely three years. At night my mother couldn’t sleep. She was anxious. Their arguments left her feeling lost. At home the ceiling under the floor that held the giant marble bathtub started to show large and dangerous cracks, dust falling onto the furniture below. My mom told my dad she wanted to go into psychoanalysis. My dad felt they should be able to work out their problems without the help of a stranger.

After finishing work on Splendor, my mom went straight to the set of West Side Story, in which she starred as Maria. She had no time to give to their shaky marriage. The ceiling under the bathtub could be reinforced; the problems in their relationship were not so easily fixed. Not knowing what else to do, they decided to separate. The failure of their relationship shattered them both. My mom later wrote that she jumped straight from childhood into matrimony without ever discovering who she really was and what made her tick. She had never stood alone on her own two feet.

In the months after they split, my mother missed R.J. terribly. She moved out of the half-renovated home they had shared together, renting a house by the beach where she tried to recover. R.J. missed her just as much, escaping to Europe, where he hoped to revive his career. He still loved her but had no idea how to restore what had been broken between them.

Splendor and West Side Story opened in October 1961 and were instantly successful. My mom earned her second Oscar nomination for Splendor. She had become an A-list actress, highly regarded by her peers. By now she had also begun working on a new movie, Gypsy, based on the Broadway musical. Professionally, this was one of the most exciting times in her career. She became totally immersed in the work. She started dating Warren Beatty, but it was not a happy relationship. She later observed that after her divorce she was looking for the “Rock of Gibraltar” and she discovered “Mount Vesuvius” instead.

My mother’s next film was called Love with the Proper Stranger, with Steve McQueen. When she wrapped that movie, she bought herself a home of her own on North Bentley Avenue in Bel-Air. The house was more modest than the one she had shared with R.J., and finally put her on a more stable footing. R.J. had returned from Europe and found success in the movie Harper, alongside Paul Newman. He had also met and married Marion Donen. My mother later wrote that when she learned R.J. had had a baby daughter—Katie—with his new wife, she wept for what might have been and for his newfound happiness.

My mother made two more great movies during the 1960s, Inside Daisy Clover and This Property Is Condemned, both alongside Robert Redford. At the time, Redford was a little-known actor, but my mom saw his promise and told the director of Inside Daisy Clover, Robert Mulligan, “I want him.” Redford was hired, and it helped to launch his career. My mom insisted he be cast in her next film, This Property Is Condemned, as well. (It was while This Property Is Condemned was still in production that she was invited to the dinner party where she met Richard Gregson, the man who became my father.)

I enjoyed hearing stories about my mother’s dating life in those years—after her second divorce, she dated Steve McQueen briefly, among others—but my favorite was the one about how R.J. and my mom reconnected. One day, R.J. asked if he could come and visit my mom and me. I was still only a little older than a year. By now R.J. had divorced his wife Marion. He arrived at the North Bentley Avenue house with his mother, Chattie. Later he told me about the first time we met. “You had a shock of solid black hair—so much so that we could have turned you upside down and swept the floor with you,” he recalled. When it was time for me to take a nap, I didn’t want to go. My mom was singing my lullaby, “Bayushki,” to me, patting my back and walking me around the room, rocking me. I refused to go to sleep. When R.J. turned around, Chattie had slid from her chair. She had fallen asleep to the sound of my mother’s singing.

The next day, R.J. sent my mother flowers. In her datebook at the top of one of the pages, she has an entry that says, “R.J. called!”

It was clear to both of them they had never stopped loving each other. Life had knocked them around, they had each married again and divorced, each had a child. They had matured beyond many of the problems that troubled their first marriage and were ready to try again.

According to a story my parents both told over the years, my mother and R.J. had first run into each other again when they were still married to their other spouses, at a party given by their mutual friends John and Linda Foreman in June 1970. My mom had come to the party without my British dad, as he was in London. At the time, R.J. was separating from his wife Marion and was also at the party alone. My mother was six months pregnant with me. The two of them struck up a friendly conversation. When the party ended, he gave her a ride home. After she was safely inside, he pulled his car over and had a good cry; my mother walked into the front door of our house on North Bentley Avenue and burst into tears. They both realized that the love they had was real, and it was as strong as ever. As my mom was still with my dad, neither one did anything about it.

Now that they were reunited and so happy, my parents decided to get married again. Their wedding took place at sea, on July 16, 1972, just off the coast of Catalina Island. Their friend Frank Sinatra arranged for them to be married on a boat called the Ramblin’ Rose. His classic song “The Second Time Around” played over the loudspeakers. I don’t remember the wedding, but to commemorate it, they had a series of portraits taken in the summer of 1972. In one they are seated outdoors, Daddy Wagner leaning in close as Mommie holds a stark-naked me in her lap, my tiny toes dangling above the long skirt of her ivory-and-lavender-checked peasant wedding dress. When I look at it, I’m floored by the sheer joy that they radiate, the Southern California sun bathing their faces. How many people get a second chance at love? My parents did and they seized it.

It’s no coincidence that my parents were married at sea. During their first marriage, my dad had a boat called My Lady and my parents spent many happy times together on it. My dad taught my mom how to fish on that boat: how to use the radio and the mooring, how to work the radar and drive the dinghy. She enjoyed becoming one of the crew. After their second marriage, around the same time they bought the Canon Drive house, my parents purchased a sixty-foot yacht my mother christened the Splendour, after the line “splendour in the grass,” from the William Wordsworth poem that had inspired the title of her film. On weekends we’d take trips to Catalina, an island about twenty-five miles off the California coast.

My parents were different on the boat—more peaceful. We all were. Even Courtney and I got along better on those weekends away. Our deckhand was a sandy-haired man from Florida named Dennis Davern who had worked on the boat even before we owned it, and took care of it year-round. Weekends on the boat, my dad and Courtney and I would be out on the deck, fishing, or my mom would be sitting next to my dad as he steered the ship. Other times, all of us would hang out together inside, playing cards or reading, or talking with the many friends that joined us on those weekends. When we docked, we would go to the arcade, where we kids could play games, then go out to a casual dinner on the island. For Courtney and me, Catalina was like an unspoiled island in a storybook, with its bright blue sea and lush, tropical foliage. From our boat, we could see the wild bison roaming on the hillsides, and dolphins and giant fish swimming around us in the waves.

Other times Daddy took us out in the motorized dinghy, and we’d spin through the craggy reefs and caves along the coast looking for garibaldi, a bright orange fish native to Southern California. Once, I remember my dad diving for abalone, and showing Courtney and me how to pound the mollusks flat with a special hammer so that we could flash fry them and eat them hot from the pan. My dad was an excellent fisherman. He taught Courtney and me how to hook the bait on the fishing line, cast our rod with a flick of our wrist, and patiently wait for the hoped-for tug. He explained how to reel the catch in slowly, using what strength we had, speeding it up as the hooked fish got closer to the top of the water. I held the record for catching the largest fish on board the Splendour: a forty-two-pound halibut, almost as big as I was at the age of ten. Reeling that salty sucker in required the manpower of all the grown-ups on the boat that day. Another favorite pastime of Courtney’s and mine was watching our guests find their sea legs. Most of them were not used to being out on the water, and soon they’d be throwing up over the side of the boat. For some reason, Courtney and I found their seasickness deliriously entertaining.

Our swimming spot of choice was Emerald Bay, off the northeast tip of Catalina, where the water is shallow, turquoise, and clear. Although my mom loved being out on the water and swimming in the heated pool at home, in general, she didn’t enjoy the colder temperatures of the ocean or “when I can’t see the bottom.” Emerald Bay was the only place where she felt comfortable swimming because she could see the sand on the ocean floor below.

Sometimes I wonder if life was ever really this sweet.