Chapter 5

Sir Laurence Olivier, Natalie, and R.J. in rehearsal for the 1976 British TV production of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.

Although her family was important to her, my mom was growing restless, less content with being a full-time mother and occasional actress. Nothing could entirely replace performing for the cameras, at least not for someone who had been starring in movies since kindergarten. She had planned and carefully constructed our domestic world, and now that it was up and running, she was ready to return to her career. It was more than a force of habit or an ego trip for her; acting was her lifelong passion.

In 1978, she began preparing for a role in the big-budget disaster movie Meteor (about which she later joked “the movie was the disaster!”). In it she played a Russian scientist, which meant she had to brush up on her Russian for the role. She found herself a Russian teacher and spent hours listening to the language on a tape recorder, perfecting her accent. I remember sitting next to her and reading my book or drawing as she listened and recited. This was the first time I can recall witnessing my mother’s diligence when it came to preparing for a role.

After that she played a recovering alcoholic in the made-for-television movie The Cracker Factory, which was filming in LA. Kilky would bring Courtney and me to visit my mother on set. As always, she was thrilled to see us, beaming with pride as she introduced us to the cast and crew. I was just as proud to be her daughter. This person that everyone wants is my person, I thought. Because The Cracker Factory was a serious drama concerning alcoholism, suicide attempts, and mental hospitals, she allowed us to watch her shooting only lightweight, PG scenes. Her favorite moment in The Cracker Factory was when her character gives a defensive, angry monologue to her doctor, in which she refuses to stand up in an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting and “confess my ninety-proof sins to a bunch of old rummies who just crawled in off of skid row!” I can remember overhearing my mom memorizing that speech at home, and sensing that she loved saying the words as much as I loved listening to them. The speech was punchy, funny—strong.

The night the movie aired on TV, my mom was out to dinner, but she’d instructed Kilky, “When it comes to the scene where I take the pills, change the channel!” She didn’t want me and Courtney to be traumatized by seeing our mom swallowing a bottle of sleeping pills and falling over. Meanwhile, I had overheard the phone conversation and was prepared. When Kilky switched the channel, I reached over and switched it right back. I wanted to watch that overdose scene! Later, when we got a copy of the movie on videocassette, Courtney and I watched our mother’s monologue over and over again and memorized all the words, which we would repeat for each other at any time of the day or night.

Once The Cracker Factory was over, she took a part in a TV series based on the 1956 movie about Pearl Harbor, From Here to Eternity, alongside the actor Bill Devane. She played the Deborah Kerr role from the movie, an emotional and sexy role—which meant that we weren’t allowed to watch her filming or to see the finished product once it was on TV. In the lead-up to filming, I remember she was excited, extremely focused, and watching her weight. Whenever she got a big part, my mom went on a diet. She was always petite, but she loved comfort food and usually put on a couple of extra pounds when she wasn’t in front of the cameras, eating whatever she liked: her beloved lamb chops, beef bourguignon, borscht, and cold cuts from the Nate’n Al deli. She and my dad liked to have deli feasts of matzo ball soup and turkey or roast beef sandwiches on rye bread, topping it all off with her favorite Häagen-Dazs coffee ice cream. Then, right before a project, she’d do a grapefruit fast, a watermelon fast, or a cantaloupe fast. She ordered plain salads “with the dressing on the side.” And of course her favorite chopped salad at La Scala, as always, “without the garbanzo beans!”

In 1979, Daddy Wagner shot a pilot for a TV series called Hart to Hart, and it really took off. He coproduced and starred as Jonathan Hart, one half of a chic, jet-setting couple who solved mysteries and were passionately in love. Stefanie Powers played his wife, Jennifer. They traveled, they sparkled, they called each other “darling.” My mother had originally been offered the Jennifer role, but my parents decided it wouldn’t be possible for them to raise children and both be working the grueling schedule of an hour-long weekly TV series at the same time.

I remember going to the Warner Bros. lot in Burbank to watch a screening of the ninety-minute pilot. My parents told us there was a surprise in the episode. Halfway through the program my mom appeared in one of the scenes dressed like Scarlett O’Hara. All in pink and carrying a parasol, playing an over-the-top movie star called Natasha Gurdin (her birth name). Yes, I was surprised and excited to see her on-screen, but it was also confounding to me. When did she shoot without me knowing? I considered myself the keeper of my mom’s whereabouts, so the fact that she had fooled me actually bothered me.

Hart to Hart became a hit pretty quickly. Courtney and I weren’t allowed to stay up late and watch it, but my parents taped every episode so we could watch the next day. Our favorite part was the opening credits. We memorized all Lionel Stander’s lines: “This is my boss, Jonathan Hart, a self-made millionaire. He’s quite a guy. This is Mrs. H. She’s gorgeous…” Every few episodes, my dad would bring home a chunky VCR tape labeled “GAG REEL,” containing all the blunders and mistakes the actors made on set. Courtney and I watched the gag reels over and over again.

Suddenly, millions of people were seeing my dad on TV in their living rooms every Thursday night. Strangers had always spotted my parents in public, but now fans were even more eager to ask for autographs, photographers more anxious to aim their cameras in our direction. Almost every time we left the house a trail of admirers would cluster around us. Because my mom and dad were both reared in the old studio system, they treated fans with respect, signing scraps of paper and smiling for pictures. I remember once a friend giving my parents matching T-shirts that said, “I’m not signing autographs, I’m on vacation.” They got a kick out of that. But they rarely complained unless a fan behaved rudely or interrupted our dinner. Only sometimes after a particularly enthusiastic devotee left, my mom would roll her eyes and make a funny sound like “OYYYYYY” and they would both smile and that would be that.

By now my parents had also revived the production company they had first started together in 1958. The original company was called Rona (an amalgam of Robert and Natalie) and the new company was Rona II. Through Rona II, they contributed to the development of the hit series Charlie’s Angels, so they received a profit from that show as well as from Hart to Hart. Ever since she’d become an adult, my mother made sure to stay in control of her finances. She was every bit the businesswoman, once saying, “You get tough in this business until you get big enough where you can hire someone to get tough for you. Then you can sit back and be a lady.” (There’s a famous picture of my mom wearing a black hat and seated at the head of a boardroom table, the only woman surrounded by ten men who worked for her: her lawyers, agents, business managers, publicists.) Both my parents were savvy about business and money. My dad’s point of view was that “The only positive is the negative,” meaning that owning “the negative”—or a piece of the film—is where you make the real money (not from your fee as an actor). After the success of Hart to Hart and Charlie’s Angels, our family was definitely in the positive.

On the nights my parents socialized outside of the house, they left us in the care of Kilky, or with my mom’s assistant, Liz Applegate. Liz was petite and delicate-looking, just like my mom, with wavy brown hair. “Hello, lovey, how are you?” she asked in her cheerful English accent whenever she arrived at our house. At four in the afternoon she drank black tea with condensed milk, so that became my favorite drink too. Liz referred to my parents as “mummy” and “daddy,” as in, “Mummy’s still out, she’ll be home later,” or “Daddy’s on the set, you’ll see him at dinnertime.” Liz was my favorite grown-up outside of my parents. She was also in charge of the other people who worked for my parents: Coralia the housekeeper, Stanley the driver, Jamie the handyman, Helen and Gene, who cooked for us. These people were so much a part of my landscape growing up, they were like members of the family.

When my parents left me in the evenings in Liz’s care, she told me stories she invented about two creatures named Billy Mouse and Morris Gerbil. Though I delighted in Liz’s stories and company, not even she could allay my concerns about my mother after she went out. By the time I was nine, I had memorized the phone numbers of every restaurant my parents frequented so I could call them before I went to bed to make sure Mommie was safe. I knew the numbers by heart: La Scala, Orlando-Orsini, Dominick’s, the Bistro, Morton’s, L’Orangerie, the Ginger Man, Bistro Garden. I knew most of the maître d’s by their first names. They recognized my voice and put my mom on the phone right away. If my parents were on the boat, I knew how to place a shore-to-ship call. “Whiskey-Yankee-Zulu 3886,” I’d say to the operator, who would connect me to the Splendour via radio.

Some nights I would get so consumed with worry I could hardly breathe until I heard my mother’s voice on the line. I was in fourth grade now and had made a new friend at school, Jessica, who had perfectly straight blond hair and loved to read as much as I did. Jessica would often stay over, and together with Kilky, she would do her best to keep me calm until I could get my mom on the line.

Our phone conversations never lasted long.

“Hi, Mommie.”

“Hi, Natooshie.”

“What are you doing?”

“We’re just sitting here finishing up dinner. We’ve been having a great time, lots of laughs.”

“Are you going out after or coming straight home?”

My mom would either respond, “We may go have a nightcap.…” or “We’re coming back now.”

If they were returning home right away, the knots in my stomach would loosen; I could take a deep breath and nod off to sleep. If they were continuing on for a nightcap, I’d hang up the phone and begin to panic. I could tell instantly if my parents had been drinking too much. Their voices got a bit louder and looser, their words sounding a little slurred like they had a cotton ball or two inside their cheeks. Kilky or Liz would try to soothe me and put me to bed. Sometimes I called a restaurant only to be told by the headwaiter, “They’ve already left.” Where are they? I would think. Are they on the way home, or have they had a terrible accident? My mind would race in circles of speculation. Inevitably, the oak front door would creak open and they’d be home. Once I heard my parents’ footsteps and laughter downstairs, I could fall right to sleep.

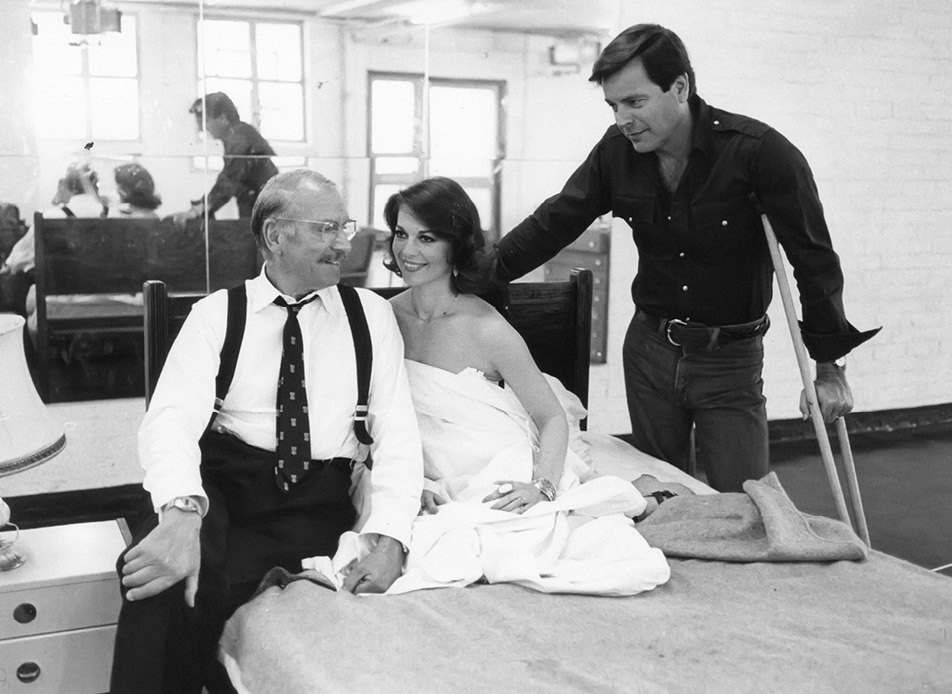

When Courtney and I were younger and my parents traveled for work, they often took us with them. For the filming of a British TV adaptation of the Tennessee Williams play Cat on a Hot Tin Roof with Laurence Olivier, our whole family traveled to England, renting an apartment in London. My mom was Maggie the Cat and my dad was Brick, the troubled wife and husband played by Elizabeth Taylor and Paul Newman in the classic movie. My mother had known Tennessee Williams, studied his heroines intimately, and hoped to perform in all his plays. Olivier took the role of Big Daddy, Brick’s wealthy plantation-owning father. One day while we were in London for the rehearsals, Courtney and Kilky and I were downstairs and we could hear my parents shouting at each other upstairs. Kilky went up the stairs. “Hey, you two, everybody calm down now. What’s going on?”

“Willie Mae,” my mom replied, “we are just acting, rehearsing for the show. Don’t worry!”

As we got older, it was harder for us to go with them on their shoots as our school wouldn’t permit us to take so much time off. In 1979, when the BBC asked my mother to go to the Soviet Union to film a TV documentary about the Hermitage Museum in Leningrad with the actor Peter Ustinov, she told us she would be going without us. It would be the first time my mom had traveled to Russia, the country where both of her parents had been born. This trip was a big deal for everyone. Courtney was okay with Kilky as her substitute mother, but I felt like the separation was going to be unbearable. Before my mom left, she tried to ease my mind by coordinating strict phone-call schedules while she was away. This was actually part of her contract with the TV people. Of course, when she got to Leningrad, the Russians did not keep up their end of the bargain. She threw a fit and threatened to be on the first plane out of there if a telephone was not put in her room right away.

While she was in Russia, I remember standing sentinel by the phone five minutes before her calls, my heart racing. Inevitably my mind would start to run away with itself. What if she doesn’t call? What if something happened to her? How will I find her? When the long, unfriendly overseas beep tone ended and the operator came on the line to say, “Person-to-person call from Miss Natalie Wood to Natasha and Courtney,” I would shriek with excitement and pent-up longing.

I could barely contain myself. “Hi, Mommie, hi, Mama, I miss you so much, you got me a present, how many more days until you are coming home?” Each call would inevitably end in tears, with Kilky swiftly removing the phone from my hand and reassuring my mom that we were fine, busy, having fun. While I was talking to my mother, the warmth and love in her voice made my sadness and longing vanish—and I felt transformed. After the receiver clicked in its cradle, it was as if all the magic had gone.

Despite my concern for her when she was away from me, my mother’s renewed attention to her career was paying off. Toward the end of 1979, she learned she had been nominated for a Golden Globe for her role in the TV series From Here to Eternity. She had won the award twice before, once in 1957 for Rebel Without a Cause and again in 1966, when she was given a special achievement award. This new nomination must have been so validating for her—she had only recently made her comeback and now she was being acknowledged for her hard work. I remember the afternoon of the awards, Courtney and I were swimming in the pool when our parents came outside to kiss us goodbye. They were all dressed up, my dad in a black tuxedo, my mom in a dark, elegant dress with layers of tulle at the shoulders, the golden ribbon cuff that my dad had given her that previous Christmas wrapped around her wrist. She carefully stepped over puddles of pool water in her heels to reach us.

Our parents bent down to receive our wet pool kisses, and then they left.

Later, we were allowed to stay up and watch the awards show. I felt a rush of excitement seeing my beautiful parents on TV looking the exact same way they had a couple of hours earlier when they’d walked out to the pool to say goodbye. I could see the expectation on my mom’s face when they read her name and then the absolute astonishment when she won. The childlike glee in her eyes made us whoop and holler at home. “Mom won, look at that, Mom won!” Kilky chanted. Courtney and I hugged each other. We were so excited. We could see the look of love in my dad’s eyes when the camera cut to him. He was always so proud of her.

After winning her award, she starred in the comedy The Last Married Couple in America, opposite George Segal, in which they played a couple struggling to stay happily married as their friends divorce all around them. In early 1980, my mom promoted her projects on the talk-show circuit, appeared in a commercial for Raintree products, and began work on the TV movie The Memory of Eva Ryker, about a woman whose mother is drowned after a German torpedo destroys a cruise ship during World War II. In the film, she played both mother and daughter at different points in their lives. The shoot took place partly in Long Beach aboard the Queen Mary. My mother organized a field trip for my entire fifth-grade class to visit her on set. We showed up on a yellow school bus, buzzing with curiosity to see my mom at work. In turn, she was so happy to have us there that she had prepped everyone on set for our arrival. She introduced us to the director, the director of photography, craft service people (my favorite), and a little girl named Tonya Crowe, who was playing my mother’s character as a child. I was shocked. Why was there another little girl playing my mom? Tonya was about my age, and I instantly wondered, Why didn’t my mom ask me to play the part of her as a little girl?

This was my first inkling I might want to be an actor when I grew up.

“Mommie,” I asked her later, “why couldn’t I have played that role?”

“When you grow up, you can make that decision,” my mom replied, perfectly composed. “Right now you’re a child and I want you to have a normal childhood.”

If my mother was spending more time working and away from her kids, at least her kids were getting along better. As Courtney grew a little older, we started to make peace with each other. She was funny and creative and pushed the boundaries further than I would, so that added a colorful layer to our make-believe play.

Katie moved in with us when she was fifteen, in 1979, and was now a popular sophomore who wore a T-shirt that said “Blondie Is a Band” and wished she could wear her hair just like Debbie Harry. After she got her license, she drove around town in a white Honda Civic and seemed to be friends with all the coolest kids at Beverly Hills High. To me, Katie was where it was at. To her, I was practically invisible. For my ninth birthday, she gave me a necklace that expressed her opinion of me: a gold chain with two charms—one was engraved with the word “spoiled,” the other “brat.” Did Katie know something that I didn’t?

Sometime around 1980, my parents’ work schedules and social lives got pushed a little further to the extreme. There were too many parties, too many vacations. Why can’t everyone just slow down? Why can’t we be a normal family where Mommie cooks dinner and has it waiting for Daddy when he gets home from work? Most fathers I knew came home from work much earlier than my father, and most dads weren’t wearing pancake makeup on their face when they walked through the front door.

Why was the phone always ringing, the intercom for the front door always buzzing?

I knew what that incessant sound meant. It was somebody coming over to distract my parents or to take them away from us.

Out to dinner, an event, the airport.

I felt my mother belonged to me, just like I belonged to her. If she was busy all the time, where did that leave me?

With a marker and a sheet of paper, I made a special calendar for myself—a chart of the nights they went out and the nights they stayed in.

I made another calendar for her.

“You’re only allowed to go out two nights a week!” I told her. “The other five nights are reserved for Courtney and me.”

My parents were sympathetic, they made all the right sounds as they tried to comfort and placate me, but even so, they didn’t change their plans. The doorbell kept ringing, and off they went again.

I cried. I raged. I told my mom I wanted to go live with Tracey. Her mom didn’t go out all the time; she was home in the evening. Tracey didn’t have to worry about when her mom was coming back. Her mom was already right there.

It wasn’t that my mother didn’t listen to me. Her therapist, whom I’ll call Dr. Fisher, told her that it was important for us to have special time together (my mom had been in therapy for many years, ever since her divorce from my Daddy Wagner). So my mother would make sure we had that. Many afternoons she would be the one to pick me up at school, taking me to my piano lessons. Even though her driving style was gas-break-gas-break, and I didn’t much like playing the piano, I loved our car rides because I had her to myself. In her car she was my captive audience. I could ask her anything my heart desired.

“Who do you think is the most beautiful woman ever?”

“Well, I guess I would have to say Vivien Leigh.”

I remember one day, my mom picked me up from school and said, “I have a surprise for you.” She drove to the MGM lot, where she had arranged a private screening of Penelope, a silly comedy she made in 1966 that practically ruined her career. Though the movie was a colossal failure, she seemed to sense that her nine-year-old daughter would enjoy it. She was absolutely right. In one scene, she dresses up like an old lady and robs a bank at gunpoint. We both laughed and laughed. I think she was also proud of the song she sings in the film, a sweet ballad called “The Sun Is Gray.” I felt so known and loved that afternoon. It wasn’t about the movie; it was that she planned a special date for just the two of us.

When it came to her social life, however, my mother remained firm. She simply wasn’t going to stay home five nights a week. Her therapist supported her independence from me, telling her that it was healthy.

Like my grandmother, I began orchestrating elaborate good-luck rituals to keep my mother safe. The carpet in the hallway leading to my bedroom was the same as the wallpaper pattern—bloodred roses and peonies entwined with green leaves, forming a garland of squares against a cream background. I made a rule for myself: when walking to my room, I had to step on the garland squares an even number of times or something terrible might happen to me or Mommie. I was gripped by the fear that my mother was going to die.

My best friend Jessica was the only one who noticed the little two-step shuffle I performed on the hallway carpet. When she came over to spend the night, she watched me quizzically. “What are you doing?”

“Oh, nothing,” I’d say, trying to be as nonchalant as possible.

Once I made it safely into my room, I couldn’t go to sleep until all twenty or thirty of my stuffed animals were lined up in a row on my brass bed, my Barbies perfectly positioned in their Barbie DreamHouse. As soon as I finished brushing my teeth and turned the bathroom lights off, I had to switch on my swan night-light. I prayed every night, “Now I lay me down to sleep…” including a special prayer to God to please keep my mom safe. Then I had to walk one complete circle around the bed before turning off the swan light. If I was particularly worried, I had the locket around my neck with the holy flowers from my grandmother inside that I would palm feverishly. I was embarrassed by these rituals but felt compelled to do them every night.

When I flip through my mother’s datebooks from 1980, they are packed with events: charity galas (she was the national chairperson for UNICEF), guest appearances (she and my dad were co–grand marshals of the Hollywood Christmas Parade), social functions, business meetings, parties, and dinners, and she still made time to entertain her inner circle at home. She kept up with Daddy Wagner’s Hart to Hart schedule better than he did, jotting a running log of his call times and making sure he was there for every shoot. As for herself, she coordinated meetings with writers and producers about projects she was interested in with costume fittings and photoshoots for current projects.

At some point that crazy year, my parents were scheduled to fly to New York City for a week. I begged them not to go. My mother tried to talk it through with me. At first she comforted me patiently and listened to my concerns, but when that didn’t work, she became increasingly exasperated. What exactly was I afraid of? She reminded me that she was just a phone call away, that I could have her number at the hotel (joking that I would have it memorized within ten minutes). She would let the front desk know I would be calling. On and on and on. Nothing could appease me.

Every time I even thought about my parents leaving for the New York trip, my heart would race and my stomach would flip over with fear. The idea of both my parents being on the other side of the country terrified me. I continued to beg them to stay. They actually considered canceling the trip, but my mother’s therapist, Dr. Fisher, told her, “You have to go, or else Natasha will think there’s something to worry about. Staying home will only confirm her irrational fears.” So Mommie gave me Dr. Fisher’s phone number in case I couldn’t reach her in New York and I needed someone to talk to.

The evening after they left, Kilky told me to take a shower, brush my teeth, and put on my pajamas, and then we could call my mom. On the scratch paper pad next to the phone in our playroom was my mother’s number at the Sherry-Netherland hotel in New York. There I stood in my footed flannel pajamas, long wet hair down the length of my back, ready to call. I dialed the number. The receptionist put me through to her room, but it rang and rang. I dialed again. And again. When I couldn’t reach her, I started to cry. My friend Jessica was there, as well as Courtney. They tried to reassure me that she was probably just out for dinner, there was nothing to worry about, that I could talk to her in the morning. Jessica went back into my room to get ready for bed, but I could not fall asleep.

Next to the Sherry-Netherland number was Dr. Fisher’s phone number. I didn’t want to call him and humiliate myself but I was desperate. I called the number, but no one picked up, so I left a sobbing, near-hysterical message on his answering machine. Dr. Fisher never called back. The next morning when I finally reached my mom she said Dr. Fisher’s wife, who was a teacher at Westlake prep school, assumed it was a prank call from one of her students. I felt the hot burn of shame knowing these important professionals in my mom’s life had dismissed my cry for help as a hoax.

After that incident, Dr. Fisher referred us to a child psychologist for my separation anxiety. Thus began my twice-weekly visits to Dr. Murray’s Beverly Hills office. Here I was, at age nine, with my very own “talking doctor.”

I did not “connect” with Dr. Murray. His office was dim, gloomy, and stocked with brown and olive-green 1970s furniture that looked utilitarian and vaguely Soviet. He was over sixty and wore ugly brown polyester suits and thick glasses with big black frames, his few remaining strands of hair stuck to his sweaty, shiny head. He never smiled. Somewhere in the back of my mind, I remember thinking, How can you help me with my anxiety if you look so uncomfortable in your own clothing? My mom was such an intimate, cozy person who wore soft, pretty clothes and smelled good. Why does Mommie think this guy can help me? I wondered.

My mom sat outside in the waiting room while I sat inside with Dr. Murray. Sometimes he would ask her to come in for a little while so we could all talk together. But for the most part, it was just the two of us. Dr. Murray sat behind his desk. He stared at me, asked questions, and scrawled observations on his notepad. I thought we were there to figure out why I was so worried about my mom all the time, why I felt so unsafe whenever she was away from me. But I don’t recall having one productive or meaningful conversation with him about my mother, her drinking, or anything else. Once, he had me play some sort of game with wooden blocks. I got so annoyed that I threw a block. It struck his forehead and knocked his glasses askew. I was horrified at myself, though he remained silent, his expression blank. He simply adjusted his glasses and continued staring at me.

I probably saw Dr. Murray for a year tops even though it didn’t seem to help. I think my mother simply didn’t know what else to do.