Chapter 14

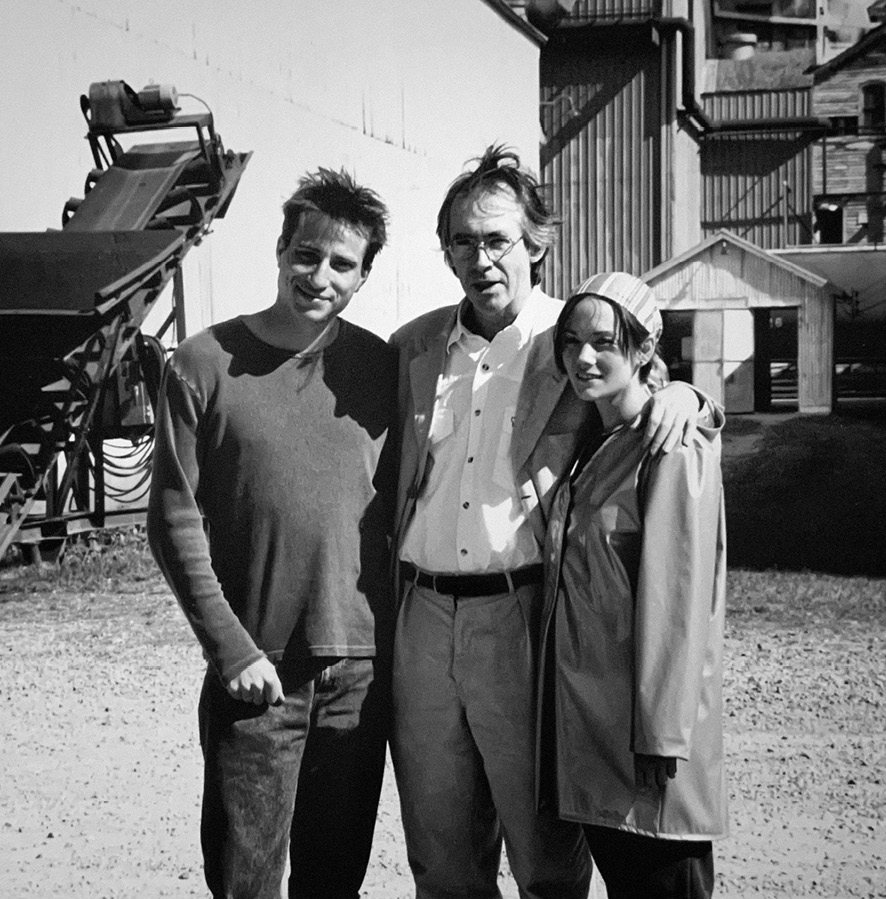

Natasha on location with Jesse Peretz (far left) and author Ian McEwan in Houma, Louisiana, for First Love, Last Rites, 1997.

Courtney’s breakdowns were dramatic. Obvious. On the outside I was the “good” daughter, capable, working, getting on with my life. But that was only the facade. My breakdowns were more secretive. Reserved for my boyfriends, my closest friends, or Mrs. Malin. I allowed Courtney to be the messy one so I could be the tidy one. I did not want people to worry about me, to pity me, to feel sorry for me—but I was living a total lie. My anxiety would sit itself in my stomach, knotting up my insides. “How do you stay so skinny?” my friends would ask me. “You eat like a horse.” And I did. I ate anything I wanted. I think my adrenaline was running overtime ever since my mother died.

When I was alone with my journals I could describe my struggles, my fears, my insecurities about not having any talent, not being as beautiful as my mom. Then there was my fear of separation, which had been with me since the earliest days of my childhood. Sometimes I could barely catch my breath when Josh left for a weekend, so terrified was I to be apart from him. I learned to go home to my apartment on Doheny to cry into my pillow exactly the way I did as a child when my mom died, take a bath, and call a friend or one of my sisters, and then I would be okay. It was just the initial trauma of separating that was so painful. I hated to be alone, and airports left my palms sweaty, my heart beating like a hummingbird’s. Even if I could talk myself through it, saying, Josh is not my mom, he is not going to abandon me, I could not stop the physical sensations that overtook me.

Josh was opinionated. Instead of arguing with him or standing my ground when he implored me to adopt his vegetarian lifestyle, I assured him that I had stopped eating meat—around him, that was. When he wasn’t there, I devoured a cheeseburger with the best of them. We fell into the roles of teacher (Josh) and willing student (me), and I quickly grew dependent on his nurturing and his advice. The more intertwined Josh and I became, the more terrified and out of control I would feel. Sometimes I acted out with other guys, blatantly flirting with them in front of Josh or mutual friends who would tell him. It was as if I was testing him, pushing the boundaries to see how far his love for me would stretch. When he would confront me, I’d become enraged, petty, and jealous. I would scream and cry and fall apart. During these emotional outbursts, Josh would always tell me, “You need to call Miss Malin.” It became an inside joke with Jessica and me, the fact that he called her “Miss.” But Josh didn’t seem to care if he got her name right. He was emotionally mature enough to know that I needed to process these unwieldy feelings with a professional, not a twentysomething.

One night I stayed out late. When I came home to Josh’s apartment at 3 a.m. he had accidentally locked me out. I was outraged, humiliated. When he finally came sleepy-eyed to the door, I let him have it. A punch would have been cleaner. Instead I raged at him from the darkest places inside of me. He sat there, he listened, he jumped up and ducked when I threw things. It was too late for me to call “Miss Malin,” so he didn’t mention it. A couple of hours later I was beset with shame and sadness. How could I have treated the one I loved so deeply, so terribly? I cried, I apologized, I curled into a ball. Josh was that rare person who was able to withstand my craziness. He was a few months younger than me and yet he had an emotional fortitude that I lacked. He was patient and strong and kind. But I knew something had to change.

After that, Mrs. Malin and I doubled down on our therapy sessions. She’d sit there in her brown leather chair, a long necklace of pearls or a gold chain around her neck, her gaze focused on me. Together, we began to see a pattern. I had gone from dating Ricky to Paul to Josh, instantly fusing myself with these boys in the same way I fused with my mom. Courtney found drugs to ease her suffering; I found relationships. Neither ultimately could take our pain away. I wanted to be with my boyfriends all the time. When we were together, I could be my stable, fun-loving self. When it was time to separate for a day, a weekend, or longer, I disintegrated into a puddle of need. Sometimes my neediness was like a little girl’s; other times I became angry, lashing out at the men in my life.

I could not make sense of my thunderbolt emotions. Where were they coming from? Especially my rage. I had had such a happy childhood. I had been adored by all three of my parents, coddled, nurtured, protected. But in therapy, Mrs. Malin helped me uncover the parts of my childhood before my mom died that were not as perfect as I remembered them to be. It was a slow and delicate process. In the beginning, I did not want to believe that my beautiful, loving parents were anything but perfect. Just like they looked in pictures. They radiated warmth and safety.

Mrs. Malin encouraged me to accept that sometimes my mother wanted to be away from me and that was okay. When I was very young, after my mom and Daddy Wagner reconnected, she would leave me for a handful of days with Baba to be just with him. Later, she was constantly out for dinners and events with my dad or traveling for work. Mrs. Malin explained that the comings and goings were on her terms, not mine, and this was why when a boyfriend left me for a trip or even for an evening, I collapsed into rage and grief.

I grew to realize that one of the reasons I had such a hard time being alone—why I would be so sad when a weekend at Daddy Gregson’s or a long holiday ended—was because when I was a child my parents had surrounded themselves with so many friends. There were always people at our house visiting, staying with us, having drinks or dinner. The message to me was that being alone was wrong—it was lonely.

We also talked about my parents’ drinking. As a child I would clock my parents’ voices when they were drinking, often waking up in the middle of the night to make sure they were safely asleep in their beds. No cigarettes smoldering in their ashtrays, no candles still lit. Was the front door locked? I carried this vigilance into my relationships.

I needed to accept the fact that my parents were not perfect. That my mother had her own bouts of sadness and anxiety. That she drank too much sometimes. This was devastating for me. To me, she was flawless and all-powerful. I was scared to view her as weak in any way. Mrs. Malin helped me to see that it was going to be impossible for me to flourish in my life without accepting some of these darker, messier truths about my mother.

Slowly, I began to accept that my parents were fallible human beings, children whose own hearts had broken at various times in their lives. I forgave my dad for his physical and emotional absence after my mom died. I began to forgive my mom for abandoning me. She did not mean to die. She drank too much; she argued with her husband, whom she adored; she felt overwhelmed. I believe she was at an artistic crossroads in her life. I know with my whole heart that had she not slipped, hit her head, and fallen into the water, she would have retied that annoying dinghy to the other side of the boat and gone back to sleep. She would have woken up the next morning and had coffee with my dad and Christopher Walken. She would have pulled herself together and come home to her children and her life. If my parents were struggling in their marriage, they would have reached out for help. My mother was a self-preservationist. She was a fighter, stronger than them all, as my godfather Mart always tells me. She would have figured it out, and my parents would have figured it out. It was a terrible, terrible accident and the only thing to blame was too much alcohol that night. My parents were not perfect like I thought they were and that was okay.

At some point, Mrs. Malin suggested I meet with a psychopharmacologist. She felt that the trauma I had experienced with my mother’s death and my subsequent emotional highs and lows could be ameliorated with medication. I was prescribed 20 milligrams of a relatively new drug called Prozac, also known as fluoxetine. About a week later, I felt so much more secure in myself. I did not wake up with anxiety every morning, my heart pounding, my stomach somersaulting. I felt like the layer of skin that had been removed when my mother died was growing back—not as strong and elastic as it had once been, but at least it was there.

While I continued with my therapy sessions, my work life took a positive turn. In 1996, I got a part in David Lynch’s movie Lost Highway. I played Sheila, the sweet girlfriend of the lead character played by Balthazar Getty. The film set my career on a new trajectory. It was my first time working with a real auteur. I knew I wasn’t a great actress yet, but when you have an artist like David Lynch in your corner, it instills you with the confidence that you can do anything, even if you don’t really believe that.

Soon after Lost Highway, I got my first leading role in the film First Love, Last Rites, Jesse Peretz’s adaptation of the short story by Ian McEwan. I loved my character, Sissel, a complex individual who would erupt in flashes of anger. I related to the aloof and frustrating way that she showed her feelings for her boyfriend, Joey. Sissel was young and experimenting with her looks, her sexuality, her power over people. I knew her. Under Jesse’s direction, I let the hair under my arms and on my legs grow out, wore long vintage dresses and shoes made for boys. Jesse got me as Sissel, and he also got me as Natasha. We became close friends. Through Sissel, I began to understand a certain part of myself—the part that could shut down so easily on people, the selfish, impatient side of me that wanted complete control in my relationships.

First Love, Last Rites was a true independent film, a labor of love with a minuscule budget, filmed on location in Houma, Louisiana. I adored every moment of it. I loved my sad, tired motel room. I loved our pink-and-blue location house on the bayou. I loved that we all rode together in one van—cast, crew, producers, and director. On the weekends, we all gathered in somebody’s room and cooked a simple and inexpensive dinner like pasta with tomato sauce. Everywhere we went it was hot and sticky and buzzing with mosquitoes. I couldn’t have been happier.

The 1990s were the golden era of indie films. I found myself drawn to projects that were small, irreverent, and experimental. I was not my mother, nor did I aspire to do what she had done. I had no interest in big-budget studio movies. I wanted to work a little bit under the radar. I wanted to take risks creatively and steer clear of the center of attention. If I stayed away from mainstream Hollywood, I thought, I could avoid the scary parts of the business that had made me feel anxious in my childhood: the throngs of fans, the magazine covers, the gossip. I felt safer in the world of indie films. There was room for me in that world.

Around the time we were shooting First Love, Last Rites, I purchased my first home, a 1,200-square-foot post-and-beam beach house on Malibu Road with white beadboard walls, hardwood floors, and large picture windows looking out over the ocean. My mom had made good business choices in her life, which in turn afforded me the kind of financial security that I knew most young actors did not have—I was so grateful for that. The house had been built in the 1950s and was painted Pepto-Bismol pink. The heavy salt air hung like a cozy blanket around me. I woke up to the sound of the waves in the morning. The frogs sang their ribbit ribbit in the evening. Every day, as soon as I got home, I opened my front door, took off my shoes, and headed toward the beach with my Westie, Oscar. The soft sand between my toes, the dark blue ocean unfolding before me, the rhythm of the tide lapping forward and backward—all of this comforted me, reminding me of childhood weekends in Malibu with Daddy Gregson and Julia. I decorated the house simply with white sofas and a few antiques from my childhood—my mother’s music box; a faded red wrought iron bench that my dad had bought when he was married to Katie’s mother, Marion; the Marcel Vertès painting of a ballerina that had once hung in our home on Canon Drive.

I was feeling grounded and confident when I auditioned for the comedy Two Girls and a Guy in the living room of a Santa Monica hotel suite. Robert Downey Jr. was there with the writer-director, James Toback. I had known Robert slightly through my sister Katie. A couple of years earlier, Robert had spent a funny Thanksgiving with us at Katie’s condo. The oven broke and Jill put the turkey in the dishwasher on the steam cycle to finish cooking it. Frank Sinatra had just released an album with Bono, and my dad, Robert, and I all sang along to “I’ve Got You Under My Skin.”

Robert and I clicked at the audition. I remember his wide brown eyes growing even wider after we read our scene together. I overheard him on the phone with his wife at the time, Debbie, saying, “Katie’s little sister Natasha just read for the movie and she is fucking awesome in the role!” I pretended I didn’t hear what he said. I had originally read for Carla, eventually played by Heather Graham. My agent called me a couple of days later to offer the role of Lou instead. Heather and I would play Robert’s two girlfriends, each believing she is in an exclusive relationship with him until we encounter each other outside his building. I was fine with playing Carla or Lou. I just wanted to be in a movie with Robert Downey Jr., who had recently gotten sober after an arrest and mandatory drug testing. He was focused and present during the shoot in New York, seemingly in a positive state of mind. We didn’t socialize much after work, but when we walked together in the morning from our hotel in SoHo to our location loft in Tribeca, he was funny and alive and sharp as a knife.

Before the shoot, Josh’s dad, Bob Evans, told me, “My darling Natasha, Jimmy Toback is a good friend of mine. I called to tell him that you are like family to me, and if he lays a fucking hand on you I will kill him.” I assumed Bob was just being overly protective, maybe because Josh had asked him to. Now it’s common knowledge that many women have accused Toback of predatory behavior toward them, but thankfully he never stepped out of line with me.

I was nervous and excited when Fox Searchlight flew me to the Toronto International Film Festival for a press tour. Two Girls and a Guy and First Love, Last Rites were both screening at the festival. I was in a bit of a fog, uncertain of my new place. Though receiving attention for two buzzworthy films, I was still incredibly insecure, unable to enjoy the parties, the success. I was happier acting with my fellow cast and crew on set. Now that the films were in the can and the world was watching, I felt doubtful of my talent and still heavy with worries about Courtney. I knew I should be on top of the world, but often I wanted to hide in my hotel room. One night I became engaged in an interesting conversation with a writer from Vogue. I kissed him sweetly on the cheek when we said goodbye. The next day I was shocked and humiliated to read his review of Two Girls and a Guy. He wrote that I was “simply not up to the task.” I was not prepared for the screenings and the reviews, which, to me, were unpleasant punctuation marks at the end of my enjoyable filmmaking experiences.

When I watch Two Girls and a Guy now, I can see how I could have grounded Lou more, given her a stronger dose of gravitas. I try to forgive myself for the inadequacies of my performance because, at that time, it was the bravest work I was able to do, and I was proud of it. I consoled myself with the fact that Robert—whose talent I admired—thought I was a good actress.

Next I auditioned for a film by Larry Clark, director of the controversial Kids. I knew who Larry was, and I loved his photography. As soon as I read the script for Another Day in Paradise, I fell hard for the character of Rosie, a drug addict. I knew Rosie. I knew how lonely and needy she was. I certainly saw a bit of Courtney in her. Set in the 1970s, the film is based on Eddie Little’s book about a teenage meth addict who becomes a safecracker to feed his drug habit. James Woods and Melanie Griffith were cast as an older couple showing Vincent Kartheiser and me how to live a life of crime.

From day one, James Woods (Jimmy) and Larry clashed. Larry’s freewheeling style didn’t gel with Jimmy’s focused and organized pace, and they were constantly at odds with each other. Instead of letting it unsettle me, I used the tension between them on the set to inform my character. Rosie doesn’t have parents, so I created a backstory for her. I decided she was an orphan and that she felt a connection with her boyfriend and with drugs that made up for her lost childhood. I made a mixtape of songs, Rosie’s blues, that I would listen to in my car driving to set and on my Walkman in between takes. Again I was using a role in a film to understand my own story, channeling my own feelings of loss into the part.

In these years of my twenties, Baba was still a presence in my life. I would call her on the phone, make a date, and then drive over to her condo on Goshen Avenue in Brentwood. Baba had always been a difficult person, and she didn’t get any easier as she got older.

“People had to endure her, not enjoy her,” Daddy Wagner once explained to me. “I told your mother I would always take care of Mud, so I tried to include her as often as possible.” My dad continued to support Baba, buying her condo for her outright and giving her a monthly stipend. Now that I was older, I became the one to see her most regularly. If I didn’t maintain a connection to Baba, no one would.

When she called me, I could tell it was her the moment I heard her drawing breath. Rapid and caught in her throat, like a hiccup, that was how excited she was to talk, to tell me what she needed. Her sputtering and humming and searching for the word she wanted to say in English sounded like the revving of an engine that doesn’t quite kick over. “Emmmmmm, ummmmm, ehhhhhh, ahhhhh, Natashinka, dis is Baba, how are you, my darrrrrlink.”

Baba continued to live in a world of her own invention. As a child, that had seemed delightful to me, but now it could be exhausting. We weren’t able to have conversations about real things. She loved me because I was an extension of my mother. She wasn’t particularly interested in who I was becoming.

When I arrived at her apartment, she would usually be putting the finishing touches on her makeup or rearranging one of her many tabletop still lifes. In her older years, Baba created miniature tableaux that she would display on glass trays: a little gold bird, a tiny birdbath, an angel. She had a way with live creatures too. I remember once she tamed two bluebirds to land on her balcony railing by feeding them nuts and seeds. Forever the romantic, she named them Romeo and Juliet and tended to them as a child tends to her dolls. Speaking in a friendly low whisper: “Good morning, Romeo, good morning, Juliet, krosheny, belochka, I love you. Lyublyu tebya.” Then she would shuffle around her house in her long dress, her feet padding the plush, white carpet.

We usually went to the Sizzler around the corner from her apartment. She loved the salad bar. Since it was not her style to ask questions about my life, we talked about her life, her fan mail, her friend Roger, whom she was usually mad at. As always, she’d be dressed like a movie star, in a jewel-toned velvet dress with lots of costume jewelry and red lipstick, her hair freshly colored chocolate brown. If a man complimented my grandmother on her dress, her voice would raise three octaves, and she would bat her eyelashes. “Oh, sirrrrr, thank you so much, you have made my dayyyyy.” Why couldn’t she see that the stranger was just being polite to a fragile old lady? Why was she so easily duped by false flattery, fakery?

I tried to be patient with Baba, to hide my frustration. I got used to holding my breath and clenching my stomach muscles to stay calm around her, hoping for the time to pass quickly so I could leave. Her childlike ways, her living in the past, her need to be known as Natalie Wood’s mother were in stark contrast to my need to move through the world unrecognized.

Every now and again, I searched her watery blue eyes for a glimpse of my mother. Where is my mom inside of my grandmother? Can I find her? No, I could not. Baba was Baba and my mom was my mom and there was no similarity that I could sense, see, or feel. They smelled different, they looked different, they spoke different.

The truth is, my grandmother was a child. She was a grown-up child. My mother had mothered her, and now in my mid-twenties, I mothered her too.

At some point it became clear that my aunt Lana, her daughter Evan, and their eight cats had moved into Baba’s condo. After my mom died, Lana had continued to write to my dad asking him for money and loans. While my father felt an obligation to support Baba, he didn’t see why he should support Lana too, so he told her no. As soon as I turned eighteen, Lana began writing to me as well. My father advised Courtney and me to refuse these requests. In our family’s opinion, it didn’t seem to matter how much money we gave Lana; it would never be enough.

After Lana moved into the condo, Baba would complain to me that her daughter and Evie needed money, which was why she turned over her Social Security checks to them every month. They had taken over the master bedroom. Baba was now in the small second bedroom. Soon, neighbors began complaining that a putrid smell was emanating from the apartment. When Liz went to investigate, she found dirty plates piled up in the sink, trash that had not been taken out for weeks, and cats and cat feces everywhere. We moved Baba out of the condo and into a one-bedroom apartment on Barrington and Wilshire in West Los Angeles. Our attorney sent a letter to Lana telling her to vacate the condo within thirty days. It took another three months to clean and disinfect the place and make it habitable.

From then on, whenever I picked Baba up, it was from her new digs on Barrington. Immediately, I noticed something about her had changed. Her lipstick was not exactly on her lips. Her hair was only partially dyed. The roots were black, but a few inches down from the roots were bands of gray, and the ends were more auburn than usual. I caught glimpses of long white hairs dangling from her chin and above her lips. Often, her beautiful velvet dresses were stained. She was forgetful, and little things seemed to confuse and overwhelm her. She was experiencing the beginnings of dementia.

We didn’t go out to lunch as much anymore; instead I ran her errands. Sometimes I would take her to visit my mother in the cemetery, and then to Ralphs, where we would stock up on her favorite food, Lunchables.

One day Liz got a call from the apartment manager saying that Baba had set her apartment on fire and had been taken to the hospital. My grandmother had become certain that nefarious people were following her every move, waiting to pounce when she wasn’t looking so they could steal from her. These wild, paranoid fantasies would compel her to hide pieces of her jewelry in bizarre places, then promptly forget where she’d put them. On this particular day, she seemed to remember that she had stashed her jewels under the bed, so she lit a candle and crawled under the mattress in hopes of discovering her buried treasure. It never occurred to her that she would set her bed on fire, which is exactly what she did. Once her bed was ablaze, Baba thankfully realized she was in danger and ran out into the hallway in her nightgown, yelling, “I am Natalie Wood’s mother and my apartment is on fire!” Her apartment was badly damaged, and it was clear to all of us that Baba could no longer live alone.

Baba moved in with Lana in Thousand Oaks, in the northwestern suburbs of Los Angeles. I visited her at Lana’s house once or twice, and then at the hospital after she was admitted with pneumonia. Toward the end, she would offer me a faint smile of recognition, but I don’t think she really knew who I was. When she died from pneumonia on January 6, 1998, her last words to me were: “You have a pretty face. You ought to be in the movies.”