L.A. The full name of Los Angeles is El Pueblo de Nuestra Senora la Reina de Los Angeles de Porciuncula. It can be abbreviated to 3.63 percent of its size: L.A.

Laconic. From Laconia, a region in the southwestern peninsula of Greece, we inherit the adjective laconic, “using language sparingly.” The inhabitants of ancient Laconia were known for their economical use of speech. During a siege of Sparta, the Laconian capital, a Roman general sent a note to the Laconian commander warning that if he captured the city, he would burn it to the ground. From the city gates came this laconic reply: “If.”

President Calvin Coolidge, a man of few words, was so famous for saying so little that a White House dinner guest made a bet that she could get him to say more than two words. When she told the president of her wager, he answered laconically: “You lose.”

(See BIKINI, HAMBURGER, LIMERICK.)

Latches. Transpose the first and last letters and you get satchel—and some satchels actually do sport latches. The longest pairings of this type are the twelve-letter deprogrammer/reprogrammed and fourteen-letter demythologizer/remythologized.

(See MENTALLY, UNITED.)

Limerick. Let us celebrate the limerick, a highly disciplined exercise in verse that is probably the only popular fixed poetic form indigenous to the English language. While other basic forms of poetry, such as the sonnet and ode, are borrowed from other countries, the limerick is an original English creation and the most quoted of all verse forms in our language.

The limerick packs laughs anatomical

Into space that is quite economical.

But the good ones I’ve seen

So seldom are clean,

And the clean ones so seldom are comical.

Despite the opinion expressed in Holland’s limerick about limericks, even the clean ones can be comical. In only five lines, the ditty can tell an engaging story or make a humorous statement compactly and cleverly.

By definition, a limerick is a nonsense poem of five anapestic lines, of which lines one, two, and five are of three feet and rhyme and lines three and four are of two feet and rhyme. Here is the classic limerick stanza:

da DA da da DA da da DA

da DA da da DA da da DA

da DA da da DA

da DA da da DA

da DA da da DA da da DA

Unaccented syllables can be added to the beginning and end of any line, resulting in an extremely flexible metrical form.

Although the limerick is named for a county in Ireland, it was not created there. One theory says that Irish mercenaries used to compose verses in limerick form about each other and then join in the chorus of “When we get back to Limerick town, ’twill be a glorious morning.”

It has been estimated that at least a million limericks—good, mediocre, and indelicate—are in existence today. Among the aristocracy of the genre, the most often quoted limericks of all time, is this creation by Dixon Lanier Merritt, who was known as the dean of Tennessee newspapermen:

A wonderful bird is the pelican

His bill will hold more than his belican.

He can take in his beak

Enough food for a week,

But I’m damned if I see how the helican.

Equally clever is this avian limerick, by George S. Vaill, about the inglorious bustard:

The bustard’s an exquisite fowl

With minimal reason to howl:

He escapes what would be

Illegitimacy

By the grace of a fortunate vowel.

When the limericist experiments with bizarre rhymes and outlandish visuals, the result is a gimerick (gimmick + limerick), as in this interdisciplinary masterpiece:

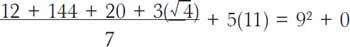

Here’s the metrical translation of the equation, which does indeed resolve into 81 = 81:

A dozen, a gross, and a score

Plus three times the square root of four,

Divided by seven

Plus five times eleven,

Is nine squared, and not a bit more.

(See BIKINI, HAMBURGER, LACONIC.)

Liverpudlian. Language maven Paul Dickson has coined the word demonym, literally “people name,” to identify people from particular places. We know that people from Philadelphia are Philadelphians and people from New York New Yorkers. But what does one call people from Indiana, Connecticut, and Michigan in the United States; Liverpool, Exeter, Oxford, and Cambridge in England; and, in other countries, Florence and Naples, Italy; Hamburg, Germany, and Moscow, Russia? The answers are Hoosiers, Nutmeggers, and Michiganians (the official name) or Michiganders; Liverpudlians, Exonians, Oxonians, and Cantabridgians; and Florentines, Neopolitans, Hamburgers, and Muscovites.

Llama, from Spanish, is the only common English word that begins with a double consonant:

A one-L lama lives to pray.

A two-L llama pulls a dray.

A three-L ama’s kind of dire.

A four-L ama’s one big fire!

If you went to the mega shopping center to purchase a certain South American ruminant, you would then own a mall llama, creating a palindromic string of four consecutive l’s.

(See CHTHONIC, LLANFAIRPWLLGWYNGYLLGOGERYCHWYRNDDROBWLLLLANTYSILOGOGOCH.)

Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrnddrobwllllantysilogogoch is the Welsh name of a village railway station in Alglesey, Gwynedd, Wales, cited in the Guiness Book of World Records. Translated, the name means “Saint Mary’s Church in a hollow of white hazel, close to a whirlpool and Saint Ryslio’s Church and near a red cave.”

In addition to being one of the longest of place-names, the fifty-six-letter cluster contains but one e. Hidden in the chain are four consecutive l’s, a five-letter palindrome—ogogo—and a seventeen-letter stretch without a major vowel—rpwllgwyngyngyllg.

The small community of three thousand souls annually attracts a quarter million visitors who take pictures of the railway station festooned with the hippopotomonstrosesquipedalian name.

(See CHARGOGGAGOGGMANCHAUGGAGOGGCHAUBUNAGUNGAMAUGG, FLOCCINAUCINIHILIPILIFICATION, HIPPOPOTOMONSTROSESQUIPEDALIAN, HONORIFICABILITUDINITATIBUS, PNEUMONOULTRAMICROSCOPICSILICOVOLCANOKONIOSIS, SUPERCALIFRAGILISTICEXPIALIDOCIOUS.)

Loll is one of several four-letter words that contain the greatest density of a particular letter. Seventy-five percent of loll, lull, and sass consists of a single consonant.

(See DEEDED, INDIVISIBILITY.)

Love. The most charming derivation for the use of love to indicate “no points” in tennis is that the word derives from the French l’ouef, “the egg,” because a zero resembles an egg, just as the Americanism goose egg stands for “zero.” But un oeuf, rather than l’ouef, would be the more likely French form, and, anyway, the French themselves (and most other Europeans) designate “no score” in tennis by saying “zero.”

Most tennis historians adhere to a less imaginative but more plausible theory. These more level heads contend that the tennis term is rooted in the Old English expression “neither love nor money,” which is more than a thousand years old. Because love is the antithesis of money, it is nothing.

(See GOLF, SOUTHPAW.)