Radar, which sounds like a Spanish infinitive, is actually an acronym for “radio detecting and ranging.” Radar is also a palindrome, an appropriate pattern for a device that bounces pulses of radio waves back and forth.

An acronym is a word-making device coined from two Greek roots: akros, “topmost, highest,” and onyma, “word, name.” Because acronyms are generally fashioned from the capital letters, or tops, of other words, the label is appropriate.

Technically, an acronym is a series of “high letters” that are pronounced as words, as in CARE (Committee for American Remittances Everywhere), NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement), MADD (Mothers Against Drunk Driving), and NIMBY (not in my back yard). Some acronyms actually become words—AWOL: “absent without leave,” snafu: “situation normal, all fouled up,” and scuba: “self-contained underwater breathing apparatus.”

Close kin to the acronym is the initialism, in which each component is sounded as a letter, as in YMCA, TGIF, LOL, OMG, and OK. The art of initialisms goes back centuries before the development of the English language. The Romans wrote SPQR for Senatus populusque Romanus, “Roman senate and people,” therein expressing their democratic conception of the State. At the end of a friendly letter they signed SVBEEV, Si vales bene est, ego vale: “I’m quite well, and I do hope that you are, too.”

The abundant proliferation of initialisms in America can be dated from the “alphabet soup” government agencies created by Franklin Delano Roosevelt during the New Deal, among them the WPA (Works Progress Administration), CCC (Civilian Conservation Corps), and FDIC (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation). It is perhaps more than coincidence that Roosevelt was our first chief executive to be known by his initials only: FDR.

(See OK.)

Raise/Raze are the only homophones in the English language that are opposites of each other. Coming close are oral and aural, petalous and petalless, and reckless and wreckless.

(See OUT, OUTGOING.)

Reactivation is the longest common word that can be transdeleted. That is, from the twelve-letter reactivation we can pluck out any letter, one at a time, and then form successively smaller anagrams, until but a single letter remains:

reactivation

ratiocinate

recitation

intricate

interact

tainter

attire

irate

tare

art

at

a

(See ALONE, PASTERN, PRELATE, STARTLING.)

A Rebus is a word picture in which letters are manipulated for their visual features to represent a word or expression. Rebus, from the Latin “by things,” appears in the phrase non verbis sed rebus, “not by words but by things.” Hence, r/e/a/d/i/n/g yields reading between the lines, slobude turns out to be mixed doubles, and HIJKLMNO must be water because it is “H to O.”

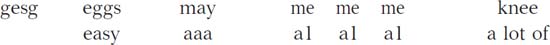

Here are some rebuses about food. Can you deduce their meanings?:

The answers are scrambled eggs, eggs over easy, mayonnaise, three square meals, and a lot of baloney.

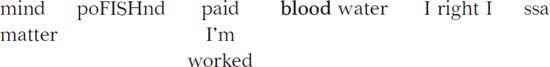

And here are some more classics, with answers immediately following:

Answers: mind over matter, big fish in a small pond, I’m overworked and underpaid, blood is thicker than water, right between the eyes, and ass backwards

And here are a stratospherically clever British rebus and translation:

| If the B mt put : | If the grate be empty, put coal on. |

| If the B . putting : | If the grate be full stop putting coal on. |

| Don’t put : over a - der | Don’t put coal on over a high fender. |

| You’d be an * it | You’d be an ass to risk it. |

(See EXPEDIENCY.)

Redundancy. We are adrift in a sea of American redundancies. The sea is a perfectly appropriate metaphor here, for the word redundancy is a combination of the Latin undare, “to overflow” and re-, “back,” and literally means “to overflow again and again,” which may itself be a bit redundant. It may come as an unexpected surprise (even more surprising than an expected surprise) that the ancient Greeks had a name for this rhetorical blunder—pleonasmós  . Redundancies, or pleonasms, are the flip side of oxymorons. Instead of yoking together two opposites, we say the same thing twice.

. Redundancies, or pleonasms, are the flip side of oxymorons. Instead of yoking together two opposites, we say the same thing twice.

Of all the adspeak that congests my radio, TV, and mailbox the one that I hate with a passion (how else can one hate?) is free gift. Sometimes I am even offered a complimentary free gift. I sigh with relief, grateful that I won’t have to pay for that gift.

My fellow colleagues and fellow classmates, I am here in close proximity (rather than a proximity far away) to tell you the honest truth (not to be confused with the dishonest truth) about the basic fundamentals (aren’t all fundamentals fundamentally basic?) of redundancies. As an added bonus (aren’t all bonuses added?), my past experience, which is a lot more reliable than my present or future experience, tells me that redundancies surround us on all sides and will not go away. Trust me. I come under no false pretenses (only true ones).

The rise of initialisms through the twentieth century and into the computer age has generated new kinds of letter-imperfect redundancies—ABM missile, AC or DC current, ACT test, AM in the morning, BASIC code, CNN network, DOS operating system, GMT time, GRE examination, HIV virus, HTML language, ICBM missile, ISBN number, MAC card, OPEC country, PIN number, PM in the evening, ROM memory, SALT talks (or treaty), SAT test, SUV vehicle, and VIN number. In each of these initialisms, the last letter is piled on by a gratuitous noun. ATM machine turns out to be a double redundancy: machine repeats the M, and the M repeats the A. If you agree with my observation, RSVP please.

(See OXYMORON, TAXICAB.)

Reek. Stink and stench were formerly neutral in meaning and referred to any smell, as did reek, which once had the innocuous meaning of “to give off smoke, emanate.” In fact, an old term for the act of smoking meats was “to reek them.”

William Shakespeare wrote his great sonnet sequence just at the time that reek was beginning to degrade. The Bard exploited the double meaning in his whimsical Sonnet 130:

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun,

Coral is far more red than her lips’ red.

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun,

If hair be wires, black wires grow on her head.

I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

But no such roses see I her on her cheeks.

But in some perfume there is more delight

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

Reek is embedded in a famous Marx Brothers’ pun. Chico Marx once took umbrage upon hearing someone exultantly exclaim, “Eureka!” Chagrined, Chico shot back, “You doan smella so good yourself!”

(See AWFUL.)

Restaurateurs. By far the longest (thirteen letters) balanced word, that is, a word in which a single middle letter, acting as a fulcrum, is surrounded by an identical set of letters. In restaurateurs, the middle r is both preceded and followed by the letters aerstu.

If one sets the requirement that the surrounding letters must appear in the same order on both sides of the midpoint, the champion words are eighty-eight and artsy-fartsy, both eleven letters. Runners up, but perhaps more impressive because they are not obvious repetitions, are the nine-letter outshouts and outscouts. The seven-letter ingoing is also nicely camouflaged.

(See HOTSHOTS, INTESTINES, SHANGHAIINGS.)

Retronym. Have you noticed that a number of simple nouns have recently acquired new adjectives? What we used to call, simply, “books,” for example, we now call hardcover books because of the production of paperback books. Now e-books are starting to dominate the market. What was once simply a guitar is now an acoustic guitar because of the popularity of electric guitars. What was once just soap is now called bar soap since the invention of powdered and liquid soaps.

Frank Mankiewicz, once an aide to Robert Kennedy, invented a term for these new compounds. He called them retronyms, using the classical word parts retro, “back,” and nym, “name or word.” A retronym is an adjective-noun pairing generated by a change in the meaning of the noun, usually because of advances in technology. Retronyms, like retrospectives, are backward glances.

When I grew up, there were only Coke, turf, and mail. Nowadays, Diet Coke, artificial turf, and e-mail have spawned the retronyms real Coke, natural turf, and snail mail. Once there were simply movies. Then movies began to talk, necessitating the retronym silent movies. Then came color movies and the contrasting term black-and-white movies. Now 3-D movies are contrasted with 2-D movies. I remember telephones that we all dialed. When push-button phones came onto the market, rotary telephones became the retronym. Then, with the conquest of the market by cell phones, land lines entered our parlance.

May the following retronyms never come to pass—teacher-staffed school, non-robotic product, non-performance-enhanced athletic contest, monogamous marriage, and two-parent family.

A rhopalic is a sentence in which each word is progressively one letter or one syllable longer than its predecessor. This word derives from the Greek rhopalos, for a club or cudgel, thicker toward one end than the other.

Here’s a rhopalic letter sentence from the great Dmitri Borgmann: O to see man’s stern, poetic thought publicly expanding recklessly imaginative mathematical inventiveness, openmindedness unconditionally superfecundating nonantagonistical, hypersophisticated, interdenominational interpenetrabilities.

Now here’s a syllabic rhopalic by me that employs more accessible words: I never totally misinterpret administrative, idiosyncratic, uncategorizable, overintellectualized deinstitutionalization.

(See HIPPOPOTOMONSTROSESQUIPEDALIAN.)

Rhythms. The longest word lacking an a, e, i, o, or u, rhythms boasts two syllables, yet only one vowel. Also syllabically efficient are schism (and any other kind of ism, from fascism to romanticism), chasm, dirndl, fjord, subtly, massacring, and Edinburgh, each characterized by fewer vowels than syllables.

(See Nth.)

Right started out in life as an adjective that meant “straight, lawful, true, genuine, just good, fair, proper, and fitting.” Only later did right come to signify the right hand or right side. Ever since, right suggests rectitude, to which it is etymologically related:

The bias toward the right side extends beyond English. One who is skilled is dexterous, from the Latin dexter, meaning “right, on the right hand,” and adroit, from the French a droit, “to the right.”

On the other hand—the left one, of course—language appears to libel the left-handed:

Bias against the left-handed minority is embedded in many languages. Sinister, the Latin for “left, on the left hand,” yields the darkly threatening sinister in English, while the French word for “left hand” is gauche, the debasement of which is gawky.

Apparently, it is not only doorknobs, school desks, athletic gear, musical instruments, can openers, and flush handles on toilets that favor the right-handed majority.

(See HAND.)

Rode is one of a handful of one-syllable words in English that morph into a three-syllable word with the addition of a single letter—rode-rodeo. Others: are-area, came-cameo, gape-agape, lien-alien, and smile-simile.

Run. What could be so amazing about this plain, little word? Turns out it’s actually our longest word, in the sense that with 645—you read right: 645—meanings, run takes up more room in our biggest, fattest dictionaries than any other word. But how many meanings can run have beyond “to move rapidly on alternate feet”? Well, you can run a company, run for the school board, run the motor of your car, run a flag up a pole, run up your debts, run your stocking, run your mouth, run a fence around a property, run an idea past a colleague, run an antagonist through with your sword, run an ad in a newspaper, run into a childhood friend, never run out of meanings for run—and your nose can run and your feet can smell.

If you need a fancy term for multiple meanings of a word, it’s polysemy. Run takes up half again as much space as its nearest polysemous competitor, put, which itself is far more polysemous than the third word in this race, set. So the three “longest” words enshrined in our dictionaries are each composed of three letters.

Rounding out the top ten most polysemous words—each but a single syllable—are, alphabetically, cast, cut, draw, point, serve, strike, and through.