S. If you look at a real-world dictionary that features little half moons cut into the edge of pages, you’ll probably find that only one of them displays just one letter, and that letter is s. That’s because s starts more English words than any other letter in the alphabet. The versatile s is also used to mark plural nouns (cats), third-person singular verbs (walks), and possessive nouns and pronouns (men’s clothing, hers).

S is all too frequently overused. It’s daylight saving time, not daylight savings time; in regard to, not in regards to; a way to go, not a ways to go; the book of Revelation, not the book of Revelations; number-crunching, not numbers-crunching; and brinkmanship, not brinksmanship.

(See A, I, Q-TIPS, SILENT, W, X.)

Salary. The ancients knew that salt was essential to a good diet, and centuries before artificial refrigeration, it was the only chemical that could preserve meat. Thus, a portion of the wages paid to Roman soldiers was “salt money,” with which to buy salt, derived from the Latin, sal. This stipend came to be called a salarium, from which we acquire the word salary. A loyal and effective soldier was quite literally worth his salt. Please don’t take my explanations with a grain of salt. That is, you, who are the salt of the earth, don’t have to sprinkle salt on my etymologies to find them tasty.

(See CAKEWALK, COMPANION, COUCH POTATO, HOAGIE, PUMPERNICKEL, SANDWICH, TOAST.)

Sandwich. In order to spend more uninterrupted time at the gambling tables, John Montagu, Fourth Earl of Sandwich, ordered his servants to bring him an impromptu meal of slices of beef slapped between two slices of bread. Thus, America’s favorite luncheon repast was rustled up to feed a nobleman’s gambling addiction.

(See BIKINI, CAKEWALK, COMPANION, COUCH POTATO, DACHSHUND, GERRYMANDER, HAMBURGER, HOAGIE, LACONIC, MAVERICK, PUMPERNICKEL, SALARY, SIDEBURNS, SILHOUETTE, SPOONERISM, TOAST, TURKEY.)

Scent is, I believe, the only word in the English language that conforms to these specifications: Think of a five-letter word in which you can delete the first letter and retain a word that sounds just like the first word, then restore the first letter, and then delete the second letter and retain a word that sounds just like the other two words. And the three words possess totally distinct meanings. Those words are scent, cent, and sent.

And scent is an exceedingly punnable sound: Have you heard about the successful perfume manufacturer? His business made a lot of scents/cents/sense.

(See AIR, WHERE.)

Scintillating shines forth from the Latin scintilla, “spark,” and means “to give off sparks.” Personally, I never sin in the morning, but I often scintillate at night.

Scintillating, is one of a number of adjectives that compare intelligence to light. Other such metaphors include bright, brilliant, dazzling, and lucid.

Clever is another intriguing descriptor for intelligence, harking back to the Old English cleave and cleaver. That history leads us to a second metaphoric cluster, one that likens intelligence to the edge of a knife, as with acute, incisive, keen, and sharp.

(See METAPHOR.)

Scuttlebutt. On sailing ships of yesteryear the “butt” was a popular term for the large, lidded casks that held drinking water. These butts were equipped with “scuttles,” openings through which sailors ladled out the water. Just as today’s office workers gather about a water cooler to exchange chitchat and rumor, crewmen stood about the scuttled butts to trade scuttlebutt.

To help you learn the ropes and get your bearings with seafaring metaphors, take a turn at the helm. The coast is clear for you to sound out the lay of the land by taking a different tack and playing a landmark game. Don’t go overboard by barging ahead, come hell or high water. If you feel all washed up, on the rocks, in over your head, and sinking fast in a wave of confusion, try to stay on an even keel. As your friendly anchorman, I won’t rock the boat by lowering the boom on you.

Now that you get my drift, consider how the following idioms of sailing and the sea sprinkle salt on our tongues: shape up or ship out, to take the wind out of his sails, the tide turns, a sea of faces, down the hatch, hit the deck, to steer clear of, don’t rock the boat, to be left high and dry, to harbor a grudge, and to give a wide berth to.

In “Sea Fever” (1902), the poet John Masefield sang:

I must down to the seas again

To the lonely sea and the sky,

And all I ask is a tall ship

And a star to steer her by.

Relatively few of us go down to the seas any more, and even fewer of us get to steer a tall ship. Having lost our intimacy with the sea and with sailing, we no longer taste the salty flavor of the metaphors that ebb and flow through our language:

, “steersman, pilot.”

, “steersman, pilot.”(See DOLDRUMS, FATHOM, FORECASTLE, METAPHOR.)

Sensuousness. Some palindromic letter patterns repose inside a word, anchored there by other letters. Five-letter anchored palindromes are relatively common, including this dozen:

banana

breathtaking

chocoholic

dissident

divisive

evergreen

hangnail

helpless

petite

proportion

revere

synonym

Step right up to a dozen six-letter anchored palindromes:

braggart

diffident

fiddledeedee

grammar

knitting

misdeeds

modeled

possesses

shredder

staccato

tinnitus

unessential

Now, here now are one last dozen anchored palindromes, each of seven letters:

assessable

footstool

hullaballoo

igniting

interpret

locofoco

monotonous

pacification

precipice

recognizing

redivide

selfless

But the grand champion of all anchored palindromes—ahead of its closest competitor by four letters—is the eleven-letter sequence embedded in sensuousness.

Note that words such as banana, petite, revere, grammar, igniting, locofoco, and redivide spell themselves backwards when the first letter is looped to the back of the word.

(See ADAM, AGAMEMNON, CIVIC, KINNIKINNIK, NAPOLEON, PALINDROME, WONTON, ZOONOOZ.)

September, with its derivation from the Latin septem, looks as if it should be the seventh month of the year. And October (octo), November (novem), and December (decem) appear in their structure to be the eighth, ninth, and tenth months. And they were, when the Roman lunar calendar started the year in March at harvest time.

But all that changed in 46 B.C., when January became the first month of the new Julian calendar, making September, October, November, and December the ninth, tenth, eleventh, and twelfth months of the year.

Several other numbers embedded in our words are deceiving:

(See QUINTESSENCE.)

Sequoia is the shortest common word (seven letters) in which each major vowel appears once and only once. Eight-letter exhibits include dialogue and equation. Sequoia is further distinguished by a string of four consecutive vowels.

A rare variant of the verb meow is miaou, and the past tense of that verb is miaoued—five consecutive major vowels and each one different!

Do many words include the major vowels a, e, i, o, and u? Unquestionably—and that word is your best answer. Ross Eckler crafted the following sentence to demonstrate that the major vowels can occur, exactly once each, in just about any order: “Unsociable housemaid discourages facetious behaviour.”

(See AMBIDEXTROUS, FACETIOUS, METALIOUS, ULYSSES SIMPSON GRANT, UNCOPYRIGHTABLE, UNNOTICEABLY.)

Set, anagrammed twice thrice, yields the triplet testes, tsetse, and sestet.

(See ANAGRAM, COMPASS, DANIEL, EPISCOPAL, ESTONIA, SILENT, STAR, STOP, TIME, WASHINGTON, WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE.)

Sex. The same letter cluster may yield different meanings and etymologies. For example, the sex in sex means “state of being either male or female,” from the Latin sexus. The sex in sextet means “six,” as in the Latin. The sex in sexton means “sacred,” from Medieval Latin sacristan. And the sex in Essex, Wessex, and Sussex shows that they are the parts of England where the East, West, and South Saxons lived.

Shanghaiings is the longest reasonably familiar word (twelve letters) that consists entirely of letter pairs—two s’s, two h’s, two a’s, two n’s, two g’s, and two i’s.

Among eight-letter exhibits are appeases, hotshots, reappear, signings, and teammate. Among ten-letter runners up we find arraigning, horseshoer, and intestines. In many of these isogrammatical words, the two halves contain the same letters and hence are anagrams of each other.

(See HOTSHOTS, INTESTINES, RESTAURATEURS.)

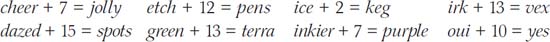

Shiftgram. Take the word add and promote each letter by one letter in the alphabet. You’ll get bees. When pairs of words are yoked together by promoted letters, we call them shiftgrams. Among shifty pairs that are semantically related we find:

and USA + 12 = gem!

In gnat +13 = tang, the two words are mirror images.

Glory be, God is the grandest of all shiftgram clusters:

God + 8 = owl owl + 4 = sap sap + 4 = wet wet + 10 = God

(See STAR.)

Sideburns. A century before Elvis Presley, the handsome face of Civil War general Ambrose E. Burnside was adorned by luxuriant side-whiskers sweeping down from his ears to his clean-shaven chin. The two halves of the general’s last name somehow got reversed and pluralized, and the result was sideburns.

(See CROSSWORD, GERRYMANDER, MAVERICK, SANDWICH, SILHOUETTE, SPOONERISM.)

Silent. I enlist you to be silent and listen to the inlets of my tinsel words. That’s five six-letter anagrams.

Now let’s listen to the sounds of silence. All twenty-six of our letters are mute in one word or another. Here’s an alphabet of such contexts to demonstrate the deafening silence that rings through English orthography:

A: bread, marriage, pharaoh

B: debt, subtle, thumb

C: blackguard, indict, yacht

D: edge, handkerchief, Wednesday

E: more, height, steak

F: halfpenny

G: gnarled, reign, tight

H: ghost, heir, through

I: business, seize, Sioux

J: marijuana, rijsttafel

K: blackguard, knob, sackcloth

L: half, salmon, would

M: mnemonic

N: column, hymn, monsieur

O: country, laboratory, people

P: cupboard, psychology, receipt

Q: lacquer, racquet

R: chevalier, forecastle, Worcester

S: debris, island, viscount

T: gourmet, listen, tsar

U: circuit, dough, gauge

V: fivepence

W: answer, two, wrist

X: faux pas, grand prix, Sioux

Y: aye, prayer

Z: rendezvous

Now consider the opposite phenomenon, words in which a letter is sounded even though that letter is not included in the spelling. In Xerox, for example, the letter z speaks even though it doesn’t appear in the base word. Behold, then, a complete alphabet of silent hosts:

A: bouquet

B: W

C: sea

D: Taoism

E: happy

F: ephemeral

G: jihad

H: nature

I: eye

J: margin

K: quay

L: W

M: grandpa

N: comptroller

O: beau

P: hiccough

Q: cue

R: colonel

S: civil

T: missed

U: ewe

V: of

W: one

X: decks

Y: wine

Z: xylophone

(See A, I, Q-TIPS, S, W, X.)

Silhouette. Long ago in prerevolutionary France there lived one Etienne de Silhouette, a controller-general for Louis XV. Because of his fanatical zeal for raising taxes and slashing expenses and pensions, he enraged royalty and citizens alike, who ran him out of office within eight months.

At about the same time that Silhouette was sacked for his infuriating parsimony, the method of making cutouts of profile portraits by throwing the shadow of the subject on the screen captured the fancy of the Paris public. Because the process was cheap and one that cut back to absolute essentials, the man and the method, in the spirit of ridicule, became associated. Ever since, we have called shadow profiles silhouettes, with a lowercase s.

(See GERRYMANDER, MAVERICK, SANDWICH, SIDEBURNS, SPOONERISM.)

Slapstick comedy owes its name to the double lath that clowns in seventeenth-century pantomimes wielded. The terrific sound of the two laths slapping together on the harlequin’s derriere banged out the word slapstick.

One of those puppet clowns was Punch, forever linked to his straightwoman Judy. The Punch that was so pleased in the cliché pleased as Punch is not the sweet stuff we quaff. That phrase in fact alludes to the cheerful singing and self-satisfaction of the extroverted puppet.

From the art of puppetry we gain another expression. Puppetmasters manipulate the strings or wires of their marionettes from behind a dark curtain. Unseen, they completely control the actions of their on-stage actors. Whence the expression to pull strings.

Because entertainment is such a joyful, enriching part of our world, show business metaphors help our language to get its act together and get the show on the road. At the opportune moment, these sprightly words and expressions stop waiting in the wings and step out into the limelight. The first limelights were theatrical spotlights that used heated calcium oxide, or quicklime, to give off a light that was brilliant and white but not hot. Ever since that bright idea, to be in the limelight has been a metaphor for being in the glare of public scrutiny. Such show biz metaphors become a tough act to follow, but their act is followed again and again.

As my last act, I shine the spotlight on a few individual words and expressions that were born backstage and onstage:

, a stage actor who, by the nature of his occupation, pretended to be someone other than himself. By extension, a hypocrite pretends to beliefs or feelings he doesn’t really have.

, a stage actor who, by the nature of his occupation, pretended to be someone other than himself. By extension, a hypocrite pretends to beliefs or feelings he doesn’t really have.You’re as real trouper to have stayed with this entry to the very end. Note that the spelling isn’t the military trooper, but trouper, a member of a theater company. A real trouper now means “one who perseveres through hardships without complaint.”

(See KEYNOTE, METAPHOR.)

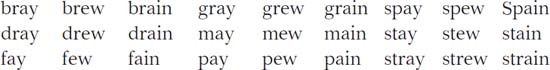

Slay is an irregular verb that declines as slay-slew-slain. Slay generates nine “illusory declensions.” These are triads of words that aren’t tenses of the same verb but that look like them because they follow the spelling pattern of slay-slew-slain:

(See TEMP, VERB.)

Sleeveless is the best example of a pyramid word, containing one occurrence of one letter, two occurrences of a second letter, and so on.

Six-letter, 1-2-3 examples abound:

acacia

banana

bedded

bowwow

cocoon

horror

hubbub

mammal

needed

pepper

tattoo

wedded

Ten-letter, four-layer pyramids are wondrous monuments. Packed in sleeveless are one v, two l’s, three s’s, and four e’s. The strata in Tennessee’s are one t, two n’s, three s’s, and four e’s. From peppertree grow one t, two r’s, three p’s, and four e’s.

(See TEMPERAMENTALLY.)

Smith. The largest category of last names began as descriptions of the work people did. In the telephone directories of the world’s English-speaking cities, Smith, which means “worker,” is the most popular last name by a large margin over its nearest competitors, Jones and Johnson (both of which are patronymics, “son of John”). And it is no wonder when you consider that the village smith, who made and repaired all objects of metal, was the most important person in the community. Two common expressions that we inherit from the art of blackmithery are strike while the iron is hot and too many irons in the fire.

International variations on Smith include Smythe, Schmidt, Smed, Smitt, Faber, Ferrier, LeFebre, Ferraro, Kovacs, Manx, Goff, and Gough. Versions of Tailor (Taylor) include Schneider, Sarto, Sastre, Szabo, Kravitz, Hiatt, Portnoy, and Terzl.

It is easy to trace the occupational origins of surnames such as Archer, Baker, Barber, Brewer, Butler, Carpenter, Cook, Draper, Farmer, Fisher, Forester, Gardener, Hunter, Miller, Potter, Sheppard, Skinner, Tanner, Taylor, Weaver, and Wheeler. Other surnames are not so easily recognized but, with some thought and research, yield up their occupational origins. My last name is an example. Lederer means “leather maker,” the German equivalent of Tanner and Skinner.

Here are two dozen surnames paired with the occupations they subtly signify:

Baxter – baker

Brewster – brewer

Chandler - candle maker

Clark – clerk

Cohen – priest

Collier - coal miner

Cooper, Hooper - barrel maker

Crocker – potter

Faulkner – falconer

Fletcher - arrow maker

Hayward - keeper of fences

Keeler - bargeman

Lardner - keeper of the cupboard

Mason - bricklayer

Porter - doorkeeper

Sawyer - carpenter

Schumacher - shoemaker

Scully - scholar

Stewart - sty warden

Thatcher - roofer

Travers - toll-bridge collector

Wainwright - wheel maker

Webster - weaver

(See APTRONYM, ELIZABETH, JOHN.)

Smithery. When anagrammed, smithery contains no fewer than seventeen pronouns: I, me, my, he, him, his, she, her, hers, it, its, ye, they, them, their, theirs, and thy.

(See ANAGRAM, DANIEL, SPARE, STAR, STOP, THEREIN, WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE.)

Sneeze. Why do so many words beginning with sn- pertain to the nose—snot, sneeze, snort, snore, sniff, sniffle, snipe, snuff, snuffle, snarl, snitch, snoot, snout, sneer, and snicker? Maybe it’s that the s sound widens your nostrils and lifts up your nose in a way that no other sound can.

And why are so many other sn- words distasteful and unpleasant—snafu, snap, sneak, snide, snobby, snitch, snit, snub, snafu, snoop, snipe, snake, snotty, snooty, and snaggle tooth? To appreciate the nasal aggression inherent in sn-, form the sound and note how your nose begins to wrinkle, your nostrils flare, and your lips draw back to expose your threatening canine teeth.

(See BASH, MOTHER.)

Southpaw. You may well know that a southpaw is a slang term for a left-handed person, but do you know why? The answer can be found in our great American pastime, baseball.

Most early baseball diamonds were laid out with the pitcher’s mound to the east of home plate. With the westward orientation of home plate the batter wouldn’t have to battle the afternoon sun in his eyes. As a result, as a right-handed pitcher wound up, he faced north—and a left-handed pitcher south. South + paw (“hand”) = southpaw.

(See GOLF, LOVE.)

Spare. As well as being marvelously beheadable—spare/pare/are/ re/e—and curtailable—spare/spar/spa—spare is the most anagrammable of all English words. Juggle spare and you get apers, pares, parse, pears, rapes, reaps, and spear, along with the rarer apres, asper, prase, and presa.

Longer words are also productive:

(See ANAGRAM, COMPASS, DANIEL, EPISCOPAL, ESTONIA, SET, STAR, STOP, TIME, WASHINGTON, WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE.)

Speech. Garnering twelve Academy Award nominations and four Oscars, including Best Picture, The King’s Speech was by far the most honored film of 2010. Among its many excellencies is the double entendre in its title. The word Speech in The King’s Speech means the speaking of George VI, the stammerer who did not want to become king. At the same time and in the same space, the word Speech means the particular address, in 1939, that King George VI delivered to his British subjects exhorting them to join in battle against the Germans.

In other words, Speech in the context of this triumphant film is an accordion word. Some of our most intriguing words, such as speech, are double-duty words that can expand and contract like an accordion. We know how big or small they are by their context.

Take the accordion word time. Time can refer to vast periods, as in “Over time, humans have built civilization.” Or time can refer to a few hours: “We had a good time at the Quimbys’ party.” Or time can be a specific moment: “What time is it?”

Then there’s the word animal, which can be used at two levels in a hierarchy of inclusion: First, animal can mean anything living that does not grow from the earth, as in “animal, vegetable, or mineral.” In this context animal includes human beings, beasts, birds, fishes, and insects. Second, animal can refer to beasts only, in contrast with human beings, as in “man and the animals share dominance of the earth.”

The use of man, above, yields another accordion word. Although the noun has come under increasing attack as sexist, man is still employed to refer both to all of humankind, as in Jacob Bronowski’s The Ascent of Man, and to only the male members of our species, as in “man and woman.” Similar is the word gay, which can designate all homosexuals, as in “gay rights,” or only male homosexuals, as in “the gay and lesbian community.”

Business started out as a general term meaning literally “busyness.” After several centuries of life, business picked up the narrower meaning of “commercial dealings.” In 1925 Calvin Coolidge used the word in both its generalized an specialized senses when he stated, “The chief business of the American people is business.” We today can see the word starting to generalize back to its first meaning in phrases like “I don’t like this funny business one bit.”

In the examples that follow, I list the broader meaning first and the narrower meaning second:

Samuel Goldwyn once observed, “A verbal contract isn’t worth the paper it’s written on.” Obviously the movie mogul used verbal to mean “oral,” as do most speakers of American English. But verbal (Latin verbum, “word”) communication involves words spoken or written, as in “I’m trying to improve my verbal skills.” In this sense, Goldwyn’s Goldwynism isn’t so funny after all.

Spoonerism. The Reverend William Archibald Spooner entered the earthly stage near London on July 22, 1844, born with a silver spoonerism in his mouth. He set out to be a bird-watcher but ended up instead as a word-botcher. That’s because he tended to reverse letters and syllables, often with unintentionally hilarious results. For example, he once supposedly lifted a tankard in honor of Queen Victoria. As he toasted the reigning monarch, he exclaimed, “Three cheers for our queer old dean!”

That was appropriate because Dr. Spooner became a distinguished master and warden of New College at Oxford University. But because of his frequent tips of the slung, he grew famous for his tonorous rubble with tin sax. In fact, these switcheroos have become known as spoonerisms.

The larger the number of words in a language, the greater the likelihood that two or more words will rhyme. Because the English language embraces a million words, it is afflicted with a delightful case of rhymatic fever. A ghost town becomes a toast gown. A toll booth becomes a bowl tooth. A bartender becomes a tar bender. And motion pictures become potion mixtures.

More rhymes mean more possible spoonerisms. That’s why English is the most tough and rumble of all languages, full of thud and blunder. That’s why English is the most spoonerizable tongue ever invented. That’s why you enter this entry optimistically and leave it misty optically.

In honor of Dr. William Archibald Spooner’s tang tongueled whiz and witdom, here’s a gallimaufry of tinglish errors and English terrors:

Welcome, ladies; welcome gents.

Here’s an act that’s so in tents:

An absolute sure-fire parade,

A positive pure-fire charade—

With animals weak and animals mild,

Creatures meek and creatures wild,

With animals all in a row.

I hope that you enjoy the show:

Gallops forth a curried horse,

Trotting through a hurried course.

Ridden by a loving shepherd

Trying to tame a shoving leopard.

Don’t think I’m a punny phony,

But next in line’s a funny pony.

On its back a leaping wizard,

Dancing with a weeping lizard.

Watch how that same speeding rider

Holds aloft a reading spider.

Now you see a butterfly

Bright and nimbly flutter by,

Followed by a dragonfly,

As it drains its flagon dry.

Step right up; see this mere bug

Drain the drink from his beer mug.

Lumbers forth a honey bear,

Fur as soft as bunny hair.

Gaze upon that churning bear,

Standing on a burning chair.

Gently patting a mute kitten,

On each paw a knitted mitten.

Watch as that small, running cat

Pounces on a cunning rat.

See a clever, heeding rabbit

Who’s acquired a reading habit,

Sitting on his money bags,

Reading many bunny mags,

Which tickle hard his funny bone,

As he talks on his bunny phone.

He is such a funny beast,

Gobbling down his bunny feast.

Sit atop three sinking wheels.

Don’t vacillate. An ocelot

Will oscillate a vase a lot.

There’s a clever dangling monkey

And a stubborn, mangling donkey

And—a gift from our Dame Luck—

There waddles in a large lame duck.

That’s Dr. Spooner’s circus show.

With animals all in a row,

(As you can see, we give free reign

To this metrical refrain.)

Now hops a dilly of a frog

Followed by a frilly dog.

Hear that hoppy frog advise:

“Time’s fun when you’re having flies!”

That’s a look at spoonerisms in one swell foop. Just bear in mind: Don’t sweat the petty things, and don’t pet the sweaty things. And let’s close with a special toast: Here’s champagne to our real friends and real pain to our sham friends!

(See GERRYMANDER, MALAPROPISM, MAVERICK, PUN, SANDWICH, SIDEBURNS, SILHOUETTE.)

Squirreled is the longest one-syllable word (eleven letters), if you indeed pronounce it monosyllabically.

The lengthiest two-syllable words come to thirteen letters:

breakthroughs

breaststrokes

straightedged

straightforth

The twelve-letter spendthrifts merits a merit badge because it may the longest word that is pronounced exactly as it is spelled.

(See STRENGTHS.)

Star is truly a star among words. Spell star backwards, and you get rats.

Next, we’ll twice progress from inside to outside, in the order of 2-1-3-4 and 3-4-2-1, and we derive tsar and arts. Star and its reversal, rats, are the only two English words that can do that.

Now, let’s transport the s to the back of star, and tars appears.

For more fun, let’s promote each letter in star by one. Voila! We find the shiftgram tubs: s + 1= t, t + 1 = u, a + 1 = b, and r + 1 = s.

The Latin word for “star” is stella, whence the name Stella, the adjective stellar, and the noun constellation.

(See ANAGRAM, COMPASS, DANIEL, DISASTER, EPISCOPAL, ESTONIA, SET, SHIFTGRAM, SILENT, SPARE, STOP, TIME, WASHINGTON, WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE.)

Startling is a nine-letter word that remains a word each time one of its letters is removed, from nine letters down to a single letter:

startling

starting

staring

string

sting

sing

sin

in

I

Similarly:

stringier

stingier

stinger

singer

singe

sine

sin

in

I

Other nine-letter words that can be transdeleted one letter at a time to form one word at a time include cleansers, discusses, drownings, replanted, restarted, scrapping, splatters, startling, strapping, trappings, and wrappings.

(See ALONE, PASTERN, PRELATE, REACTIVATION.)

Stop. The STOP you see on traffic signs yields six different words that begin with each of the letters in STOP:

Our landlord opts to fill our pots

Until the tops flow over.

Tonight we stop upon this spot.

Tomorrow post for Dover.

(See ANAGRAM, COMPASS, DANIEL, EPISCOPAL, ESTONIA, SET, STAR, WASHINGTON, WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE.)

Strengthlessness is the longest common univocalic word—one that contains just one vowel repeated (sixteen letters, three e’s). Next come defenselessness (fifteen letters, five e’s), then sleevelessness (fourteen letters, five e’s).

Assesses is the longest word (eight letters) with one, and only one, consonant repeated throughout, five times in eight letters.

(See ABRACADABRA, DEEDED, MISSISSIPPI.)

Strengths. One of a number of nine-letter words of one syllable and the longest containing but a single vowel. Among its strengths is the fact that it ends with five consecutive consonants.

Nine-letter, one-syllable words with more than one vowel include:

scratched

screeched

scrounged

squelched

stretched

(See SQUIRRELED.)

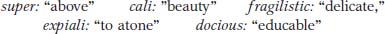

Supercalifragilisticexpialidocious is a thirty-four letter word invented for the film version of Mary Poppins (1964) that has become our best known really, really big word. Etymologically, this is not entirely a nonsense word:

Stitched together, supercalifragilisticexpialidocious means “atoning for extreme and delicate beauty [while being] highly educable.”

The word has also inspired what I believe to be the most bedazzling syllable-by-syllable set-up pun ever devised:

One of the greatest men of the twentieth century was the political leader and ascetic Mahatma Gandhi. His denial of the earthly pleasures included the fact that he never wore anything on his feet. He walked barefoot everywhere. Moreover, he ate so little that he developed delicate health and very bad breath. Thus, he became known as a super callused fragile mystic hexed by halitosis!

(See CHARGOGGAGOGGMANCHAUGGAGOGGCHAUBUNAGUNGAMAUGG, FLOCCINAUCINIHILIPILIFICATION, HIPPOPOTOMONSTROSESQUIPEDALIAN, HONORIFICABILITUDINITATIBUS, LLANFAIRPWLLGWYNGYLLGOGERYCHWYRNDDROBWLLLLANTYSILOGOGOCH, PNEUMONOULTRAMICROSCOPICSILICOVOLCANOKONIOSIS.)

Sweet-toothed is a hyphenated example of a word containing three adjacent double letters.

(See BOOKKEEPER.)

Swifty. Starting in 1910, boys grew up devouring the adventures of Tom Swift, a sterling hero and natural scientific genius created by Edward Stratemeyer. Many of Tom’s inventions predated technological developments in real life-—electric cars, seacopters, and houses on wheels. In fact, some say that the Tom Swift tales laid the groundwork for American science fiction.

In Stratemeyer’s stories, Tom and his friends and enemies didn’t always just say something. Occasionally they said something excitedly, sadly, hurriedly, or grimly. That was enough to inspire the game called Tom Swifties. The object is to match the adverb with the quotation to produce, in each case, a high-flying pun. Here are my favorite Tom Swifties (says Lederer puntificatingly):

(See DAFFYNITION, PHILODENDRON, PUN, SPOONERISM.)

A synonym (from the Greek “same name or word”) is a word that has an identical or similar meaning to another word. Some wag has defined a synonym as “the word you use in place of the word you’d really like to use but can’t spell.”

You should not be aghast, amazed, appalled, astonished, astounded, bewildered, blown away, boggled, bowled over, bumfuzzled, caught off base, confounded, dumbfounded, electrified, flabbergasted, floored, flummoxed, overwhelmed, shocked, startled, stunned, stupefied, surprised, taken aback, thrown, or thunderstruck by the o’erflowing cornucopia of synonyms in our marvelous language. Boasting a million words—more than four times the number in any other language—English possesses the richest vocabulary in history.

If you don’t believe me, please read the following announcement:

I regret to inform you that yesterday, a senior editor of Roget’s Thesaurus assumed room temperature, bit the dust, bought the farm, breathed his last, came to the end of the road, cashed in his chips, cooled off, croaked, deep sixed, expired, gave up the ghost, headed for the hearse, headed for the last roundup, kicked off, kicked the bucket, lay down one last time, lay with the lilies, left this mortal plain, met his maker, met Mr. Jordan, passed away, passed in his checks, passed on, pegged out, perished, permanently changed his address, pulled the plug, pushed up daisies, returned to dust, slipped his cable, slipped his mortal coil, sprouted wings, took the dirt nap, took the long count, traveled to kingdom come, turned up his toes, went across the creek, went belly up, went to glory, went the way of all flesh, went to his final reward, went west—and, of course, he died.

The opposite of a synonym is an antonym; that is, synonym and antonym are antonyms. Aside from the usual antonymic pairings—black and white, good and bad, rich and poor, fat and thin—antonyms can be formed anagrammatically, in which case they are called antigrams:

filled/ill-fed

fluster/restful

listen/silent

marital/martial

Satan/Santa

united/untied

and by deleting internal letters:

animosity/amity

avoid/aid

communicative/mute

courteous/curt

cremate/create

deify/defy

encourage/enrage

exist/exit

feast/fast

friend/fiend

inattentive intent

injured/inured

intimidate/intimate

patriarch/pariah

pest/pet

prurient/pure

resign/reign

resist/rest

spurns/spurs

stray/stay

threat/treat

un-huh/uh-uh

vainglorious/valorous

wonderful/woeful

Now that you know how to transdelete letters from the middle of words, I hope that I no longer intimidate you. Simply remove the id from the middle of intimidate, and the result is intimate.

(See DRUNK.)