In recent chapters I have looked, one by one, at the various tree-planting and other environmental projects we undertook from the 1960s to the 1980s. Lanark changed beyond recognition during those years, and we, the Fentons, changed, too. Cicely and I grew older—and our children grew to adulthood. Fortunately, we did not have to send the children away to boarding school, so we were able to watch them growing up. All four went to the primary school at nearby Branxholme, which was then, and still is, a typically caring country school. The four were able to do their secondary schooling locally, too—at Hamilton College, an excellent Uniting Church co-ed school in Hamilton—thanks in part to the fact that a school bus ran past Lanark’s front gate.

Our children grew up knowing virtually all there was to know about the business of farming. They learned it on the job, too. All four helped with work on the farm, especially during school holidays. They did all the usual tasks: fencing, marking lambs, rouseabouting at shearing time and, of course, planting trees. They also had their own day-to-day responsibilities. Johnnie provided us with daily fresh milk by looking after and milking a cow; Amanda looked after the chooks and kept us in eggs; David and Patrick both set up workshops where they met the family’s needs in various ways. David learned to plait leather and made belts for us. Patrick worked in leather, too, and became the family’s shoe repairer. We never paid them for the work they did: it was accepted as being part of growing up on a farm. Looking back now, it occurs to me that, collectively over the years, our four children did a huge amount of work on the place. They made a genuinely important contribution to Lanark’s development.

By 1980, all our children had left school. All four went on to do farm work of one kind or another. Amanda could have gone to university after leaving school, but she decided against it in the end, preferring to work on the land. She did farm work in New Zealand, England and Scotland, and in 1987, after returning to Australia, she married Charles Fairbairn-Calvert, a grazier who also does a lot of cropping. Their property, Banongill East, is near Skipton, west of Ballarat. I am pleased to say that at Banongill East she and Charles have done many of the things we did at Lanark: reinstating wetlands, protecting remnant vegetation and planting large numbers of trees (more than 30 000 at a recent count) both as shelter belts and timber woodlots.

After leaving school Patrick went to Canada on an international rural exchange program, and he later worked with the Department of Agriculture in Hamilton. David went overseas, too, and worked on a farm in Scotland for a while, but for the most part his working life was centred on Lanark. In 1992 he took over as Lanark’s manager. Johnnie tried his hand in various lines of work around Australia, all the while gathering valuable know-how and experience. Most of the work he did was in one way or another connected with the rural industry—contract harvesting on grain properties and working as a mechanic on a remote cattle station in Western Australia—although for several years he was the publican at the Beachport Hotel in Beachport, South Australia. He also went to England with a touring cricket club and stayed on there for a stint of farming. Johnnie is now running his own building business in Robe, South Australia.

A question of huge importance soon presented itself: what were we to do with Lanark in the long term? I explained earlier how my father had left the property not to me but to my children, the idea being this would save me having to pay death duties. Under the terms of his will, each of our four children was entitled to a quarter of the property. Now, it was obvious that a property of Lanark’s size would be able to support only one owner, so we needed to come to some mutually acceptable agreement on how family assets, including Cicely’s, would be distributed. So in the early 1990s we got the four children together to work out an estate plan. Our solicitor and accountant were there too. Today, succession planning is becoming a fairly common practice, but it was not common in the early 1990s, so in that sense we were ahead of our time. Our daughter, Amanda, was married by then, but all three boys were still single, which made the exercise a good deal less complicated.

An agreement was duly reached, under which David was to end up with Lanark, Patrick would get Vasey Farm, John would end up with a property that we bought in the Wimmera (Johnnie preferred cropping to running livestock) and Amanda would receive some money in return for her share of Lanark. Admittedly, this is a simplified summary of what was agreed, for the agreement did involve some fairly complex juggling of money and property between the four children. The end result, though, seemed fair and acceptable to all, and it meant that the question of how the estate was to be shared was sorted out long before the sharing had to take place. I commend the idea of estate planning in advance to any farming family in a similar situation.

In one sense, we were lucky there was still much of an estate to share, because for years, off and on, Cicely and I had struggled to make ends meet. We were under financial pressure of varying degrees for quite a long time—from the early 1970s, probably, through to the early 1990s. There were numerous occasions during this period when survival became a real battle—when the farm was simply not earning enough money to pay the bills. On one occasion, when funds were particularly scarce, Cicely took a job in Melbourne. That was around 1990. She based herself there for six months, working at a nursery and living at the home of the nursery’s owners, who were in the US the whole time, setting up a nursery. One sometimes hears of married women who choose to go back to work after their children grow up, perhaps because they are bored with being at home or perhaps because they are seeking personal independence. This was certainly not true in Cicely’s case. She did not leave the farm and take a job because she wanted to; we simply needed the money.

I once took a job in Melbourne myself, working for Tract Consultants, the firm of landscape architects and planners I spoke about in the previous chapter. Cicely and the children ran the farm between them in my absence. In the end, the job came to nothing, as did, eventually, our company Rural Trees Australia. I had hoped my earnings from Rural Trees Australia would subsidise our farming operation at Lanark

A familiar combination: me with trees to plant. Courtesy of Jim Sinatra and Phin Murphy

Dr John French’s ‘coppice-with-standards’ plantation he persuaded me to establish in 1985.

Graeme Gunn (left) with Cicely and our son Johnnie, shortly before Johnnie left for England in 1985.

An example of pines growing in conjunction with a permanently fenced indigenous habitat component, 1991. As the photo shows, red gum sleepers were still used then in railway tracks.

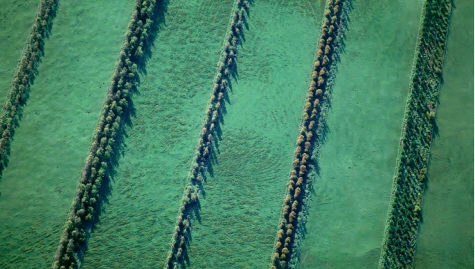

The aerial photos on the following pages, taken in 1992, show the result of 35 years of environmental rehabilitation at Lanark. Instead of a barren, windswept expanse, there were now 100 000 or more trees and extensive wetlands. Photos supplied by David Hay and Don Thomson and taken by Lindsay Stepanow, Ballarat

Bill Funk arrives at Lanark in 1993 with a ute full of oak seedlings ready for planting. In the background are, from left, Cath and David Fenton, Michael Shenks and Rochelle Ruddock. Michael and Rochelle later married.

My daughter Amanda with one of the trees she helped me plant in ‘her plantation’ at Lanark in 1962.

Below: Shorn sheep shelter from the wind in 1992 behind the plantation of mainly she-oaks that Amanda and I planted 30 years earlier.

Rod Bird (centre) with two South American agricultural scientists who had come to inspect our environmental work at Lanark.

I was delighted when Jim Sinatra (centre), and Top End grazier Bob Purvis (right) from Atartinga Station visited Lanark.

These RMIT students seem interested enough in what I have to say about a cypress plantation at Lanark. Courtesy of Jim Sinatra and Phin Murphy

The Hut. Left to right: my brother-in-law David Peddie, David Fenton and children, Murray Gunn and a visiting English ornithologist.

and enable Cicely and me to continue our environmental work there without being stressed financially. But this was not to be.

Financial necessity also forced me to sell an 1100-acre (450-hectare) property that I would dearly have liked to hang onto. I bought it in the mid-1960s. A big part of its appeal was that it adjoined the Mount Richmond National Park, which is close to the coast, twenty minutes west of Portland. Another part of its appeal was that it included 100 acres (40 hectares) of virgin forest. I was only in my mid-thirties then, but, knowing how long trees take to mature, I was already counting the years and wondering if I would live long enough to see a mosaic of shade and shelter at Lanark. At Mount Richmond, the trees were already there.

In the end, I was obliged to sell the Mount Richmond farm. My bank manager called me into his office one day in 1981 and told me that interest rates had risen and that I had to reduce my debt by selling the property. I told him I had just planted 100 acres of pines there, plus 100 acres of lucerne. The former meant nothing to the bank manager. I am sure I was the only farmer he knew who was planting pine trees. It was no use arguing with him, so I just did what he told me and Mount Richmond was sold soon afterwards.

We did scrape by in the end, but only just. As I discovered, scraping by is not a pleasant experience. In our case, this was not because we had to go without. As a family we may have been severely restricted in where and how often we took holidays, for instance, but we never went without necessities. No, the really distressing, debilitating thing about being stretched financially is the emotional toll it takes—the stress that it imposes, day after day, night after night. I certainly suffered from stress because of it. Cicely, I know, suffered more than me.

Why were we doing it so tough? The simple answer is that we spent so much time, energy and money on our environmental work at Lanark that we did not have enough time, energy and money to spend on our farming business. We were both well aware of this at the time. Yet, even when our financial worries seemed all but overwhelming, I do not think that either of us ever regretted doing what we had done at Lanark. Of course, by the 1970s, when we first encountered hard times, the results of our environmental work were already there to be seen and enjoyed. The trees we had planted were changing the landscape. All kinds of wildlife had moved into the bushland reserves we had created. If we had run into financial trouble in the early 1960s, however, when there was little to show for the environmental work we had begun only a few years earlier, we would have found it much harder to press on. Quite possibly, we would have given up.

In the light of all this, what hope do ordinary farmers have of being able to rehabilitate their properties environmentally? Sure, planting trees is good, but how many trees does a farmer need to plant and what is the secret of getting them to grow? And how much better off will the farmer be once the trees have grown? I will set out what I have discovered about these and other relevant issues in the final third of this book, beginning in the next chapter with perhaps the most important issue of all: farmers may want to restore their properties environmentally, but can they afford to do it?