CHAPTER ELEVEN

Wherein Contrarianism

Bursts Forth

Taking a Closer Look

at Wine’s Conventional Wisdom

By ERIC ASIMOV

It doesn’t take a lot of knowledge to be considered a wine expert. Sadly but surely the key to earning respect for your wine aptitude—or more accurately for intimidating others—is simply to hold forth loudly and repeatedly.

This is one reason that what is undeniable one year is laughable the next. Here are some widely repeated assertions, and some explanations suggesting that nothing is that simple.

ASSERTION No-oak chardonnay is better than oaked chardonnay.

TRUTH Oaky may be bad, but oak is good.

Back in the 1990s, when the fashion for big, bombastic, oaky chardonnays was at its height, nobody would have taken this belief seriously. Fashion has changed and oak barrels have now been branded the villain for previous excesses. The fact is, for aging wine, no better vessel than oak barrels has yet been discovered. How those barrels are used is another question.

New oak can imbue a wine with all sorts of flavors, including vanilla, chocolate, coffee and just plain woody. But many people tired of over-oakiness, and so came chardonnays, mainly from Australia and California, called “No Oak,” “Metallico” (for the steel tanks in which no-oak chardonnays are made), “Inox” (a French term for steel) and the like.

The no-oak method can produce wines that are lively, pure and delicious. It’s also much cheaper for winemakers than buying new barrels every year. But wines made in this style lack some of the crucial benefits of barrel aging, namely a very slight exposure to the oxygen that passes through the wood, which can enhance a wine’s texture and complexity. One way to retain the benefits of barrel aging while avoiding its excesses is to use older barrels, which impart fewer or no flavors to wine. Many great chardonnays in California and in Burgundy are made this way.

The bottom line: No-oak is an alternative style, but not necessarily a better one.

ASSERTION Red wine with meat, white with fish is an archaic rule.

TRUTH It’s really not such a bad guideline.

In the last 20 years the matching of foods with wines has become an exercise in wizardlike precision. Seemingly every aspect of ingredients, cooking methods, seasonings and the position of the moon must be figured into selecting the one wine that will marry, as they used to say, with the food. This exercise has been carried to absurd lengths.

Many guidelines in books and periodicals make sense, but they require esoteric knowledge of wine regions, producers and vintages well beyond what most people might be expected to have. That’s why simple generalizations are made. Most people don’t want to work at wine-and-food pairing, they just want something that will taste good.

For red meat, red wine is a no-brainer. Might you find a white wine that will go with steak or lamb? Sure, but it’s likely to be a very unusual wine. Will there be differences if you choose a Chianti or a Washington cabernet? Yes, but they’ll both be enjoyable.

For fish, dry white wine is the odds-on choice. Exceptions and nuances? Indeed. California chardonnay is better with lobster or scallops than with oysters or sole. Sauvignon blanc, Muscadet and Champagne are versatile, and light-bodied reds will go beautifully with salmon, tuna and more assertive fish. But so will many whites.

Then there’s the great in between—poultry, pork and the rest. White’s fine. So’s red. So are semi-sweet wines like Mosel rieslings. In this area you can truly drink what you like.

The bottom line: Matching food and wine is not sweat-worthy.

ASSERTION The lower the grape yield the better the wine.

TRUTH Most vines have an ideal yield below which the quality of the grapes does not improve.

While the issue of grape yields has moved from a subject for wine geeks to a vehicle for marketing, it is based on a crucial truth: The quality of the grapes is inversely proportional to the yield of those grapes. Roughly speaking, the more grapes you harvest from a vine, the more dilute those grapes will be. Conversely, farmers who reduce their yield will harvest grapes with juice of greater intensity.

The truth, naturally, is never so simple. Yields depend on many variables, including the type of grape, the age of the vines, the soil in which they are planted, the type of rootstock, the trellising system and the climate. Overly high yields may never produce very good wines, but lowering yields won’t improve grapes planted in the wrong places, while unnaturally low yields can result in unbalanced wines.

The bottom line: Yields should be based on sound viticulture, not marketing.

ASSERTION It doesn’t matter how big a wine is if it’s balanced.

TRUTH Good whiskey is balanced, but you wouldn’t want to drink a bottle with dinner.

Of all the current wine shibboleths, this is the one I hear most frequently. It generally comes from producers who want to rationalize their high-alcohol wines, and it is guaranteed to set off a heated debate over the importance of a wine’s alcohol content.

High-alcohol wines have always existed, like Amarone and certain cuvées of Châteauneuf-du-Pape, and alcohol levels have been rising all over the world, but only in California and Australia do so many wines come in at 15 percent or more in alcohol. These wines can be complex, well-made, even balanced, so the heat of the alcohol does not stand out. But these wines almost always feel huge, seem sweet, and tend to dominate food. You cannot drink as much of them.

The bottom line: Big is fine if you drink wine as a cocktail; not so good with food.

October 2007

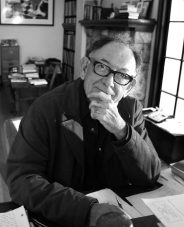

Berkeley’s Wine Radical, 35 Years Later

By ERIC ASIMOV

Photo by Peter DaSilva.

The 1980s were a dark time for French wine, as Kermit Lynch told it in his 1988 book Adventures on the Wine Route: A Wine Buyer’s Tour of France. Much of it was plain bad. What was good was made by hand, with traditional methods passed on through the generations.

But the young were turning away from their fathers to embrace technology like mechanical harvesters, sterile filterers and chemical pesticides and herbicides. They were sacrificing their heritage and turning over wines to what he called “men in white lab coats.” Mr. Lynch was appalled, and said so.

People apparently listened. While Adventures was a lament for a disappearing world, Mr. Lynch now is confident that the wines he loves, made naturally and expressively, are here to stay.

“Am I optimistic?” he said as we stood in his unprepossessing wine shop, tasting some of the myriad wines he imports, almost entirely French with a smattering of Italian. “Absolutely. Look at all the importers who do now what I was doing back then.”

Thirty-five years have passed since Mr. Lynch first hung up his shingle as a wine merchant here in the cradle of radical youth. While he is the first to say he was not much for politics back then—naïvely selling South African wine until his customers brought up the issue of apartheid—his efforts as a wine importer and merchant shook up the world of wine in the best Berkeley tradition. It is no exaggeration to say that a significant segment of the fine wine industry today is stamped in Mr. Lynch’s image.

His influence can be seen almost any time you go into a good wine shop and spot people looking at the labels of wines to check the importer. Instead of memorizing esoterica about producers, regions and vineyards, these canny consumers learned that finding an importer they can trust is a reliable navigational tool. Nowadays, many names they follow are those of the spiritual descendants of Mr. Lynch.

If he had been only an importer, Mr. Lynch would have left a significant legacy. With little company, he traveled the back roads of France, seeking esoteric producers whose wines were fresh, delicious and unaffected by the industrialization shaping the post–World War II wine industry.

The little-known names he turned up are now a pantheon of French country wines: Henri Jayer, Raveneau, Coche-Dury and Hubert de Montille in Burgundy; J. L. Chave, Auguste Clape, Thierry Allemand and Vieux Télégraphe in the Rhône; Didier Dagueneau in Pouilly-Fumé; Charles Joguet in Chinon; and Domaine Tempier in Bandol.

But like Frank Schoonmaker, another significant figure in American wine history, Mr. Lynch was not merely a merchant and an importer but an author as well. He began in the 1970s by writing descriptions of his inventory and sending them out to customers—“little propaganda pieces,” he called them.

They were really much more than that, for Mr. Lynch never engaged in the sort of contrived tasting notes that often pass for wine writing today. Instead, he wrote of the joy and pleasures of consuming good wine, of the winemakers he met and the places he visited. He provided characters, context and travelogue, and even recipes.

In 2004, many of these pieces were gathered into a book, appropriately called Inspiring Thirst (Ten Speed Press). It’s the commercial companion piece to Adventures on the Wine Route, which, even after 20 years, remains one of the finest American books on wine.

Today, Mr. Lynch still travels the back roads, though he has more company. Once, he struggled to persuade his discoveries to sell their wines in the United States. “These days it’s more about finding who doesn’t already have an importer,” he said.

That has taken him beyond the more familiar regions, into Languedoc and Cahors, to Irouléguy in the French Basque country and to Corsica. The wines are distinctive, fresh and alive, all with a clear sense of place.

We tasted several dozen of his offerings, standing in the middle of his cluttered store, which sells only wines that he imports, most in cardboard cartons with minimal display. Many of the most interesting wines were under $20, like a 2005 Cahors from Clos la Coutale, which smelled of wild berries and flowers, and an elegant yet chug-worthy 2006 Vin de Pays de la Vallée du Paradis from Maxime Magnon.

“How can anybody say that French wines are all expensive?” he asked. “I’ve never seen the dollar this low, but French wines are still the best values.”

Mr. Lynch is notorious in northern California for not selling any California wines. He shrugs. “I promised in my first brochure, I won’t sell you anything I haven’t tasted,” he said. “I didn’t have room for anything else.”

These days, Mr. Lynch spends half his time in Provence, where he and his wife, the photographer Gail Skoff, and their two children have a house not far from Domaine Tempier, the Bandol estate where he spent many formative hours with the Peyraud family. He counts the late Lucien Peyraud, the guiding spirit of Tempier, along with Richard Olney, the late food writer who introduced him to the Peyrauds, as his two primary influences.

“There was a guy on each of my shoulders when I went around looking for wines,” he said. “One was Lucien, and one was Richard, and I asked myself: ‘Would I serve this to Lucien? Would I serve this to Richard?’”

Mr. Lynch is also now a winemaker himself. In 1998 he joined with the Brunier family of Vieux Télégraphe to buy Domaine les Pallières in Gigondas, which makes big, chunky reds scented with black olives and herbs. “They say, ‘Oh, he only likes light wines,’ but sometimes you want big wines,” he said. “Finesse does not mean little.”

At 65, Mr. Lynch is by no means stepping back, although he leaves more time for other pursuits, like playing guitar and writing songs. But he takes great satisfaction in the thought that the wines he loves are still here.

“They can never be mainstream, but they’re out there,” he said. “I feel like I won.”

November 2007

A Rosé Can Bloom in Winter, Too

By ERIC ASIMOV

If you look really hard, you will find them condemned to a dusty back shelf underneath a few cobwebs, or perhaps looking forlorn on the half-price rack, their once brilliant colors dulled by neglect.

They are the rosés of winter, remnants of last summer’s lighthearted cheer. Now, they are disregarded, disdained or, at best, a benign recollection, like a poolside flirtation, pleasant but inconsequential. Next June, when the bottles pop up again like pink flowers in the prime selling soil of every wine shop, the enthusiasm will return. But for now, forget it.

More than any other wine, rosés suffer from a sort of seasonal affective disorder. Near the end of summer, sales begin to slow. By winter they are depressed, if not dead. It really makes no sense. For most wines, the old seasonal guidelines are largely passé. We drink reds all summer, whites all winter. But rosé? Because it is marketed as a summer accessory, its relevance evaporates at all other times of the year.

But what if we consider rosé as a wine, rather than as a prop? Who wouldn’t want a rosé like a 2009 Domaine Ilarria any time of the year? This $17 wine, a shimmering, translucent garnet in summer sun or winter snow, comes from Irouléguy in the Basque country, about as far southwest as you can go in France without crossing into Spain. As fierce as rosés ever get, it’s made of tannat and cabernet franc, and it tastes like liquid rock, combined with iron and blood. I love this wine, and it was terrific recently with roasted duck and wild rice.

Sadly, most rosés shrivel up next to a wine like the Ilarria. The unfortunate truth is that many rosé producers have little ambition beyond the palatable. They’ve seen crisp, innocuous rosés sell wildly in springtime, destined for poolside sipping and no more. So they are content to produce inoffensive, assembly-line wines, made quickly to accentuate immediate fruitiness, but that, like hothouse vegetables, have little or no character.

Now, I have nothing against carefree wines. I love them, in fact. But I have no interest in banal wines that are rushed into fermentation, hustled out of the winery and dead by the end of summer. Those rosés in the dusty sale bins? Many deserve to be there because they’re not worth drinking. They weren’t worth drinking in the summer either. Good rosés are another matter entirely.

“It’s the terror that lives in the hearts of retailers and distributors, of having leftover rosés that they have to close out,” said David Lillie, an owner of Chambers Street Wines in TriBeCa. Chambers Street is that rare retailer that keeps an active supply of rosés throughout the year, up to two dozen in the spring and summer, and nine or 10 through the winter.

“We feel like they’re beautiful food wines, at least the ones made in a real, serious style,” Mr. Lillie said. He concedes that 95 percent of his rosé business is in the spring and summer, but nonetheless he believes in them year-round. “It’s a very small segment, but we just happen to like to do it.”

That segment would never deprive itself of a wine like the 2009 rosé, or rosato, from La Porta di Vertine, a small producer in Chianti territory. This wine is made of a mixture of the red sangiovese and canaiolo grapes and the white trebbiano and malvasia. The fermentation is allowed to proceed at its own pace—the 2009 took six months, rather than the matter of days for industrial rosés. The result is a richly hued, textured, juicy yet substantial wine that smells like pressed flowers and would go beautifully with a good ham.

Yet the prejudice—what else can one call it?—endures. In a Twitter post, Lockhart Steele, the founder of Eater.com and other Web sites, suggested that few excuses were acceptable for drinking rosé in January. Well, excuse me, Mr. Steele, you’ve obviously never tried a wine like Jean-Paul Brun’s 2009 Rosé d’ Folie, a minerally pink Beaujolais that I would drink any time of the year, especially if I had a plate of chicken roasted with garlic, rosemary and thyme.

You want Bordeaux? How about a Bordeaux rosé like Château Jean Faux’s ’09, clean and refreshing yet sumptuous, with a pleasant heft to it? Or a Burgundy rosé, like Domaine Bart’s Marsannay ’09, its color a little darker than salmon, light textured with flavors of flowers and licorice that cling to the mouth after you swallow. All of these wines are priced at less than $20, great values at any time of the year.

I haven’t even mentioned the greatest rosés of the world, like the deep, complex Bandols from Tempier and Pradeaux, or the cerasuolo d’Abbruzzo from Valentini, wines that can age and improve for years. And speaking of aging, what about the great Viña Tondonia rosado from López de Heredia, the venerable Rioja producer? These wines are not even released until a decade or more after the vintage. The current rosado is the 2000, a pale, coppery, complex wine that compels you to smack your lips at the tactile pleasure of rolling it around your mouth. Jamón ibérico, please!

We’ve been talking about dry rosés, but another category exists as well, good, sweet rosés. It’s small, to be sure, epitomized by the once-famous rosé d’Anjou, and unlikely to grow given the aversion of former white zinfandel drinkers to residual sugar.

I confess, I can’t say I’m thrilled by rosés with residual sugar, either. Yet when an exciting producer like Éric Nicolas of Domaine de Bellivière issues a ripe, rich, balanced, lightly sweet rosé like Les Giroflées, I am willing to fly my rosé flag high, even in January. Residual sugar? Bring on the Indian food.

January 2011

So Who Needs Vintage Charts?

By FRANK J. PRIAL

About a decade ago, Bruno Prats, then the owner of Château Cos d’Estournel, in St.- Estèphe, declared that there would be no more bad vintages of wine. At the time I considered his remarks the height of arrogance, a characteristic not unknown among the Bordelais.

I was wrong.

His was a bit of an overstatement, perhaps, but essentially, Mr. Prats was right on the mark. Great wine may still be elusive, but rarely now does a year go by that doesn’t produce good wine, even in marginal regions like Bordeaux, where the weather is as risky as a dot-com stock.

The fact of the matter is that in the cellar and the vineyard the winemakers of the world have rendered the vintage chart obsolete.

For the uninitiated, a vintage chart tracks various categories of wine over a period of years. Most vintage charts use numerical ratings; some add a code indicating whether the wines are too young to drink, ready to drink or seriously past their prime.

Over the years I have produced vintage chart after chart, always adding enough qualifications and caveats to make the reader wonder why I bothered in the first place. I am not alone. Each year, Robert M. Parker Jr. publishes a vintage chart of daunting thoroughness. This year’s has 28 separate wine categories. Even so, he warns: “This vintage chart should be regarded as a very general overall rating slanted in favor of what the finest producers were capable of producing in a particular viticultural region. Such charts are filled with exceptions to the rule. Astonishingly good wines from skillful or lucky vintners in years rated mediocre, and thin, diluted, characterless wines from incompetent or greedy producers in great years.”

Vintage charts assume a high degree of homogeneity: Northern California, the Central Coast, the South Central Coast. But can a single rating for Northern California adequately cover the northern reaches of Mendocino, the furnacelike valley floor of Calistoga and the fog-shrouded hills of Carneros? And what about the Amador County vineyards, far to the east? In Sonoma County, the wines of Dry Creek are different from those of the Alexander Valley, which are not the same as those from the Russian River or the Sonoma Coast.

The first vintage charts came from France and were compact cards with listings for Bordeaux, Burgundy, Beaujolais, the Rhône, Champagne and the Loire. Today, superior wines are made in Alsace, the Languedoc, in Roussillon and the Southwest, often when wines from more traditional regions are less than exciting.

Can any single vintage chart do justice to Italy, where there are a hundred different wine regions, where remarkable wines might be made in the foothills of the Alps and in Sicily in the same year that mediocre or poor wines come from Tuscany and Umbria?

A chart might report conscientiously that, say, 1997 was a good year in Spain. Where in Spain: Penedès? Rioja? Navarre? Priorat? Rueda? Ribera del Duero? And what of the newest wine sources—Chile, Argentina, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa? Don’t they deserve space on the charts? And even if they got it, what chart could show their growing diversity?

Both Chile and Argentina are developing new wine regions far to the south of their traditional vineyards; Australia’s Margaret River region is 2,000 miles from its Hunter Valley; South Africa makes different wines in Hermanus from what it does in Stellenbosch.

A vintage chart will advise, say, that the 1998 Bordeaux will need several years of bottle aging after they arrive here in 2001. But a consumer finds the shops already filled with 1998s that are, he is told, ready now. Of course, the chart concerns itself only with the classified growths, the finest of the Bordeaux wines, and ignores the hundreds of lesser wines, many of which, these days, are startlingly close to their better-known siblings in quality.

The vintage chart speaks to wine regions at a time when winemakers—and consumers—are increasingly concerned with terroir, the uniqueness of small plots of land. Some vintners now produce five or six separate wines from half a dozen small contiguous vineyards, while others make two or three different wines from the same vineyard.

There are highs, like 1945, 1961 and 1982 in Bordeaux and 1994 in the Napa Valley, and lows, like 1991 or 1992 in Bordeaux and Tuscany, but not one year when some decent Bordeaux wine was not produced. But it’s unlikely that we will ever see vintages like 1963 and 1965, dreadful years in Bordeaux that resulted in dreadful wine. There will always be years when nature doesn’t cooperate, like 1991 and 1992 in Bordeaux, but even in those years, pleasant, drinkable if not age-worthy wines were made.

Everywhere, hardier rootstocks, better grapes, limited yields and severe grape selection at harvest time have increased quality. So, too, have new organic methods of pest and disease control and new planting techniques. In the 1960s, wine was made much as it had been made in the 1860s. Now, NASA satellites tell growers where to plant and which efforts have been the most successful.

This is not quite a golden age of wine; in spite of everything there will always be dull or poorly made wines around. But those are not problems of the vintage. And competition, which is keener than ever, makes it difficult for plonk to survive in the market.

Vintage charts are not entirely passé. Wine can be confusing, and the chart does offer some general information, as Mr. Parker, the critic, suggests. And of course, in the auction rooms, where collectors haggle over the 1982 Pétrus and the 1994 Romanée-Conti, vintage charts can serve as a handy reference tool. Elsewhere, though, vintages are increasingly irrelevant.

And I don’t think I’m alone in that point of view. In the past, letters would begin to come in about a year after the last vintage chart appeared here. When, they asked, would the next chart appear? No longer. A lot of people must be deciding for themselves.

In the final frames of Little Caesar, Edward G. Robinson snarls, “Is this the end of Rico?”

To my way of thinking, that sacred talisman of the wine buff, the vintage chart, is just as dead as Rico was when the screen went to black.

February 2000

Three Cheers for the Also-Rans

By ERIC ASIMOV

The quest for greatness is the stuff of myth and romance. Americans revere the star-bound strivers, whether Lincoln or Edison, Babe Ruth or Muhammad Ali, Bill Gates or Warren Buffett, who aimed to be the toppermost of the poppermost, as the Beatles used to say, and made it. Few remember the good, the competent, the runner-up.

When it comes to wine, though, the focus on greatness comes at a significant cost in both pleasure and money. This is most obvious in terms of wine ratings, where consumers irrationally (at least from a wine lover’s perspective) chase after bottles that critics have awarded 90 points or more, but shun those in the 85 to 89 range, even though the lower-rated wines may be cheaper, more flexible with food and readier to drink.

Less obviously, this fixation on greatness plays out with vintages. Each spring the wine-drinking world waits breathlessly as critics descend on Bordeaux for the first tastings of the previous year’s vintage, which is unfinished and still in barrels. Raves for the vintage can stampede the herd and send prices skyrocketing, as happened with the 2000, 2003 and 2005 vintages. More measured responses can provoke yawns and ho-hums, as happened with 2001, 2002 and 2004. Yet none of those three vintages was badly received. Each was considered very good. They just weren’t great.

That’s fine with me. In the latest catalog from Sherry-Lehmann, you can buy a 2003 Saint-Julien from Léoville Barton (a vintage rated 95 by Robert M. Parker Jr.) for $160. No thank you. But I would consider the 2001 Léoville Barton for $75. Why the discrepancy? Mr. Parker awarded 2001 only 88 points, even though he gave the individual bottles 95 for the ’03 and 92 for the ’01. In this case, I prefer the ’01 vintage to the ’03.

The tyranny of the great vintage is not restricted to Bordeaux. Wherever vintages matter in the wine-producing world, consumers are infatuated with the great ones while paying little attention to wines from good vintages, even when they are significantly less expensive.

Sometimes lesser vintages can offer better experiences. In restaurants I look for red Burgundies from the 2000 vintage. Most critics would rate that vintage as among the weaker ones of the last 10 years, not bad but certainly not as good as ’99 or ’02, and the wines are generally less expensive.

But they are delicious right now, at a time when the higher-rated ’02s and the ’99s tend to be in sullen adolescent phases. Ten years from now, those denser wines will most likely be in top form while the lighter 2000s will be on their way out.

If you buy wine with long-term aging in mind, the overall quality of the vintage might be more important to you. But for current drinking, you have to approach things differently.

As with the 2000s, the very decent 2004 Burgundy vintage is destined to be overshadowed, in its case by the 2005s. I don’t dispute the greatness of 2005, but those wines are going to be very expensive and will require aging. Meanwhile the ’04s are more affordable and the reds from good producers have been charming at an early age. I expect I’ll be enjoying them as the 2005s begin their slow march toward drinkability.

Not so long ago I bought some 2004 Morey-St.-Denis from Fourrier, a producer I like a lot, for about $40 a bottle. You can be sure the ’05s, when they go on sale, will be a lot more expensive.

Vintage tyranny is alive and well in Italy, too. In Tuscany, Brunellos di Montalcino are more valued from the 1997, 1999 and 2001 vintages than they are from 1998 and 2000.

The critics aren’t wrong about the vintages, but the ’98s and ’00s are pretty good, too, and should not be sneered at. Similarly the Piedmont region had excellent vintages from 1996 to 2001.

These wines are still very young in Barolo terms, but in restaurants they are generally priced higher than bottles from, say, 1993, which was a very good year. A 1993 Monprivato from Giuseppe Mascarello is selling for $135 at Del Posto in Chelsea, while the ’96 is $175. I have no doubt the ’96 is ultimately the greater wine, but right now I’d prefer to drink the ’93.

Northern California hasn’t had a bad year in a while, according to the critics, but I remember winemakers complaining bitterly that they couldn’t sell their 2000 or their 1998 vintages because they were rated badly.

Let’s be clear about winemakers: they have no bad vintages. If they’re not great, they’re “classic style” or, at worst, “difficult.” Nonetheless, I loved the light-bodied, elegant 2000 Insignia from Joseph Phelps Vineyards, even if it wasn’t as big and rich as the 1999 or the 2001, both considered superior years. This is not to say 2000 was a better vintage, only that vintage is not necessarily destiny.

Vintage ratings, like wine ratings in general, have a powerful psychological effect on consumers. The higher the number, the greater the desirability of the wine, which feeds into the myriad reasons people make their buying decisions. It should be no surprise that, as with cars, clothes, handbags and other consumer goods, status seeking, showing off and fear of embarrassment all play important roles.

If there were any doubt that beliefs influence judgment in wine, researchers at the California Institute of Technology showed in a recent study that people enjoyed wine more if they thought it was more expensive.

As 20 volunteers were given sips of cabernet sauvignon, scientists scanned their brains, measuring neural activity in areas thought to register pleasure. They were told they were tasting five different wines, and they were given the price of each.

In reality, only three wines were used, and each volunteer had two duplicates at different prices. The experiment showed that the pleasure response increased when the volunteers believed they were drinking a more expensive wine.

I don’t think we need a study to say this applies as well to wine ratings and vintage ratings. For now, value hunters can thank the rules of mass psychology.

February 2008

Screw Tops Gain Acceptance Worldwide

By FRANK J. PRIAL

Two years ago, the announcement that a well-known winery, or a little-known winery for that matter, was switching to screw caps for its bottles was news. Winemakers were divided on the subject. “Right on,” said the younger vintners. “Waste of time,” said older and presumably wiser types. Or “Money down the drain.” Or, more often, “The consumer will never accept it.”

No longer. Acceptance of screw-on tops for wine bottles—by both winemakers and consumers—has been astonishing. From Burgundy to Beaujolais, from Spain to South Africa, winemakers are switching from corks. No one seems to have an accurate count of how many wineries are using aluminum tops, but people in the industry agree that the number is in the hundreds.

Corked wine—wine that has been spoiled because of a bad cork—is a serious problem in the wine business. It affects even the fine old chateaus. Many years ago, I spent a weekend at Château Lafite-Rothschild, tasting very old wines from its cellar. Later, the staff acknowledged that it had had to open many more of the priceless bottles than we tasted, mostly because of faulty corks.

James Laube, an editor of Wine Spectator magazine, reported two years ago on a tasting of elite 1991 California cabernets in which nearly 15 percent of the wines were spoiled by bad corks.

Some of the problem is physical: as corks age, some dry out and crumble. Others were poor fits to begin with and allowed too much air into the bottle, oxidizing the wine. But the contamination derives principally from trichloranisole, or TCA, a substance formed by the action of chlorine on cork bark or wood.

Traditionally, corks were bleached in a chlorine solution as part of the manufacturing. Other substances have been used but, despite major efforts by the cork industry and regular announcements that the problem had been eliminated, it persists. Winemakers estimate that up to 5 percent of all bottled wine is contaminated by TCA. Cork producers say the figure is much lower.

The industry was hardly unfamiliar with screw tops. For years, jug wines and cheap fortified wines had been closed with them. Some years ago, when the E.&J. Gallo Winery switched from screw tops to corks for its famous Hearty Burgundy, it was an unmistakable sign that the wine had increased in stature.

Most objections to screw-top wine bottles appear to be directed at restaurants, where their presence has more to do with image and prestige than in the home. This is certainly true of expensive wines. But restaurateurs who have used screw tops on moderate-price wines say they have encountered little objection from customers. And anyone who has used the bottles at home—or who has taken screw-top wines on a picnic—quickly sees how convenient they are.

A small Napa Valley winery called PlumpJack broke the ice, so to speak, in 1997, offering a $135 cabernet with a screw top. Bonny Doon Vineyard in Santa Cruz followed, first putting screw tops on 80,000 cases of its moderate-price wines and later moving to bottle all of its wines, including its top-of-the-line Cigare Volant, with screw tops.

Among the other California wineries that have switched wholly or in part to screw caps are Beringer Blass, Calera, Sonoma-Cutrer, Murphy-Goode, the Napa Wine Company, Whitehall Lane, Robert Pepi, R. H. Phillips and E.&J. Gallo, which is using metal caps for its huge Turning Leaf line. Fetzer Vineyards uses screw caps on wines it exports to Europe. In Oregon, WillaKenzie and the Argyle winery in Dundee are using screw caps.

Hogue Cellars in Washington is to switch to screw caps next year for its 450,000 case annual production. Hogue and R. H. Phillips are owned by Vincor International, a Canadian company. Vincor also owns Kim Crawford Wines in New Zealand, which has been using screw caps exclusively since 2001. In both New Zealand and Australia, it is estimated that 40 percent of all wineries—about 200—use screw tops.

Specially treated corks and plastic corks have met with little enthusiasm in the wine business. The best-known screw cap, with a long seal covering the bottle’s opening, is the Stelvin, made by Pechiney Capsules of France. Pechiney has a factory in California.

The Stelvin was first developed in the 1970s for Swiss wines, which are said to be sensitive to TCA. Since then, the market for Stelvins has expanded to include Australia, New Zealand, Argentina and Chile, as well as the United States.

Customers in France include Michel Laroche, who bottles a premier cru Chablis under screw caps, Yvon Mau in Bordeaux, Domaine Blanck and Georges Lorentz in Alsace and the Domaine de la Baume in the Languedoc. Fortant de France, one of the best-known Languedoc wines, is now bottled with screw caps. Even Bodegas Torres in Spain, a major cork-producing country, uses Stelvins on some of its white wines.

Tesco, the largest wine retailer in Britain, has more than 100 screw-capped wines in its stores and expects more. Georges Duboeuf, the largest of the Beaujolais producers, ships some of his wines to Tesco in screw tops. Switzerland, too, sells Duboeuf Beaujolais in screw tops, but Mr. Duboeuf said last week that he produces only about 30,000 cases with screw tops. While the market for his screw tops is increasing, he said, he is also using plastic corks. They are, he said, entirely satisfactory and will probably be a more important replacement for cork than the metal caps.

Most producers have been hesitant to use screw caps on wines destined to age. Ironically, they are the wines that probably need them most because even corks not tainted with TCA dry out over time and fail to keep delicate old wines safe from air.

But 98 percent of all wine is drunk within six months after its purchase. I am willing to predict that within a decade, 75 percent or more of these wines will be sold with metal caps.

April 2004

The only thing harder than getting people to accept a good idea is getting them to abandon a bad one. A relevant example: the almost universal reverence for old wines.

Let’s suppose for a moment that we’re eavesdropping on a small gathering of wine connoisseurs. A lot of good food has been eaten and good wine drunk, and now it is time for the high point of the evening, the opening and tasting of a rare old bottle. For sake of argument, we’ll say it’s a 1945 Château Mouton-Rothschild. It could as well have been a 1958 Beaulieu Vineyards Private Reserve or some Burgundy of equally impressive age and lineage.

The wine is opened. Tension mounts. There is sniffing, swirling and, finally, tasting. Affirmative nods follow; also appreciative murmurs and ecstatic sighs. The wine, we conclude, is terrific. But wait; listen to what these sages have to say: “Fantastic; tastes like a young wine!” or “It’s still full of life,” and “It’s got the color of a wine bottled last year!”

What they are saying, what they are exclaiming over, in effect, is that the wine, in spite of its great age, still displays some of the charm of its youth. The inescapable conclusion: If youthfulness is such an asset, why all the fuss over age?

It is a bit more complicated than that, of course. A truly great old wine combines the subtlety of age with the freshness of youth, taking care to see that the latter does not overwhelm the former. But a lot of old wines are not truly great. They are just old. Which means they are brown in color and musty in the nose, and taste like dried leaves. To a dedicated expert, perhaps, these wines have some information, some arcane pleasure to impart. Like listening to a French tenor on a 1910 wax cylinder. For most of us, old wines are just something to be able to say we’ve had.

The wine trade, unfortunately, works hard to foster the old-wine myth. Even inexpensive bottles are often pictured in beautiful wine cellars, surrounded by other wines hoary with age. Novelists and screenwriters dote on them. Thomas Mann wrote about the ’28 Veuve Clicquot; James Bond said, “Ah, the ’69 Bollinger.” Demimondaines order by vintage with not a clue as to what the wine is like. In fact, we all pull that trick once in a while. It’s easier to memorize a few vintage numbers than to learn about the wine.

I’d hate to know how much money is spent by anxious hosts of a Saturday afternoon, buying a few bottles at the last minute and hoping some impressive-looking label dating from the Johnson administration will complement the lamb and wow the guests. And guests rarely know any more about wine than their host. Those who do know that a simple, fairly inexpensive wine is often more fun to drink. Nothing is more irritating than having to praise a wine because the label is impressive. To people not well versed in wine, old wines rarely taste great.

There was a time when wines achieved great old age because it took them many years to become drinkable. A century ago, the winemaking process was still basically empirical. Vintners knew what was happening but not why. So, little could be done about controlling tannin and alcohol in wine. Tannins, which can take years to soften, more than anything determine the age of a wine. Today, wines are made to mature much more quickly and, consequently, to be drunk much younger.

The most famous red wines of Bordeaux, the Lafites and Latours and Margaux and Moutons, are made to last, and there is no doubt that they get better as they get older. But even these rare and expensive wines usually reach their peak at around 10 years of age. Hundreds of lesser wines of the Bordeaux region are usually ready to drink in two or three years.

Some of the greatest Bordeaux wines, those from St.-Émilion and Pomerol, rarely mature as well as the best of the Médoc and Graves wines. Thirty-year-old Château Pétrus, for example, the most famous of the Pomerols, is rarely the equal of a great Médoc of the same age. Some fine Burgundies will last for decades, but few of them will improve after 10 years in the bottle. Most good Burgundy is ready to drink, is at its peak, after five years.

California wines age, too; some of them quite well. Probably only a handful will achieve great old age and remain drinkable. It’s too early to tell. There aren’t that many wineries more than 15 years old and most winemakers make modest claims for their first three or four vintages.

Perhaps the collecting and drinking of old wines should be seen as a pastime apart from the fundamental enjoyment of wine. But no one who seeks to enjoy wine as part of everyday life should be too concerned with antiquity. There is too much good wine around, from last year’s Beaujolais to the year before’s zinfandel to the Burgundies of two years before that.

These are the wines that are available now, that are meant to be enjoyed now and replaced by other wines tomorrow. Rare old wines have their place, but probably not at the dinner table tonight. Rare old books are beautiful to behold; but they don’t have much to do with reading.

January 1987

A Sommelier’s Little Secret: The Microwave

By WILLIAM GRIMES

A new question is creeping into wine service in New York: How do you want that cooked?

For many years, Americans have confounded the rest of the world by drinking their white wines too cold and their red wines too warm. Sommeliers no longer hesitate when diners ask that a luscious Corton-Charlemagne be plunged into an ice bucket. They just do it. It’s easy.

Red wine poses a different problem, since it often arrives at the table with a slight chill. If the diners want their wine the temperature of a blood transfusion, and fast, the sommelier must resort to wiles, and the wiliest wile of all, it turns out, is the microwave oven.

Sometimes it’s the customer who wants his wine ’waved. Sometimes it’s the hard-pressed sommelier who makes the decision to go nuclear. But it happens. There really are wines that go into that silent chamber at 58 degrees and come out, like a client at a tanning salon, flush with radiation and 7 to 10 degrees warmer.

“There is no way any sommelier is going to admit to doing it,” said Dan Perlman, the wine director at Veritas. “They’ll say, ‘I’ve heard of it,’ like I just did. I’m in the clear, though, because we don’t have a microwave.”

The practice is by no means widespread, or even widely known, but it is something that happens at even the top restaurants. Alexis Ganter, the wine director at City Wine and Cigar, reacted with stunned silence when informed about the microwave trick. Then he let out a long, shuddering sigh and moaned, “Oh my God.”

Like other members of the “wine is a living thing” school, Mr. Ganter expressed deep fear of this new technological breakthrough. Others showed a native American willingness to at least experiment. “It makes sense,” said Ralph Hersom, the wine director at Le Cirque 2000. “I don’t see that it would harm a wine, but I’d recommend doing it with a younger wine.”

Still others fessed up, some expressing shame but others not. “I did it once when I was working at a wine bar in Madison, Wis.,” said Eric Zillier, the wine director at the Hudson River Club. “It was an ’85 Burgundy from Verget, one of my favorites, but I made the customer, who was very insistent, swear he would never tell anyone I did it.”

Christopher Cannon, at the Judson Grill, has used the microwave and doesn’t mind saying so. It’s a method of last resort, but it is a method that works, and he will use it. “I zap it for 5 to 10 seconds,” he said. It seems more reasonable than the customer who wanted his Gaja Barbaresco served with ice cubes.

And why not? Most Champagne houses turn their bottles by machine, not hand. The plastic cork and the screw top work just as well, if not better, than a cork. So why resist the microwave?

“The microwaves are heating the water, which is the main constituent of wine,” said Christian E. Butzke, an enologist at the University of California at Davis. “If you do that for a very brief period—10 seconds maximum—no other chemical reactions are going to take place, and nothing will be destroyed.”

The phenolic structure of the wine, Mr. Butzke said, should not be disturbed by the microwaves. “It is awkward,” he admitted, “because you associate a microwave with TV dinners.”

Winemakers, somewhat surprisingly, do not run screaming from the room at the idea. “It’s not something I’d do with a fine wine,” said Richard Draper, the winemaker at Ridge Vineyards, “but if it’s an industrial product, which 90 percent of wine is, it’s been through a lot worse already.” As for fine wines, Mr. Draper said that his objection to microwaving was philosophical rather than rational.

Some wine lovers even see magical powers in the microwave. Richard Dean, the sommelier at the Mark Hotel, used to serve a wine club that gathered once a month at the Honolulu hotel where he worked. The members were convinced that warming a red wine in the microwave for five seconds put an extra five years of age on the wine.

A professional to the tips of his fingers, Mr. Dean did not laugh. He did not argue. Nor did he tell his customers that the hotel had no microwave. He simply disappeared with the wine, reappeared after a decent interval, served it, and everyone was happy—until a rival hotel snitched on him. “That was embarrassing,” he said.

The same sommeliers who shrink before the microwave do not mind employing all sorts of nontechnological tricks, like running a decanter under warm water before pouring the wine in it, replacing glasses on the table with glasses that have just come out of the dishwasher, or even putting the bottle in the dishwasher. Joseph Funghini, the wine director at the Post House, said that he has wrapped a bottle in a warm towel. Others plunge the bottle into a bucket of warm water.

Nearly every restaurant, bending to American preferences, has raised the storage temperature from classic cellar temperature, which is 55 degrees, to about 60 degrees. (Wines in long-term storage remain at 53 degrees to 55 degrees, with a humidity of 70 percent.) “Ninety-five percent of customers will object to 55 degrees,” Mr. Hersom of Le Cirque said.

Some object to 75 degrees. “I had a customer, very sophisticated, who simply liked to drink red wine at body temperature,” said Mr. Perlman of Veritas. “He asked that it be decanted and then placed on a shelf above the stove.” Mr. Perlman has a lot of stories like that. There’s the customer who wanted the Champagne decanted, to get rid of those annoying bubbles, and the one who wanted to add fruit juice to his Mouton-Rothschild to make a sangria. Mr. Perlman suggested a more modest red. The customer said no. He wanted a good sangria.

The microwave, however, seems to be the philosophical point of no return. Some sommeliers simply cannot cross the threshold.

“You’re destroying everything in the wine that makes it wine,” Mr. Zillier of the Hudson River Club said. “It’s catastrophic.” When informed of Mr. Butzke’s line of argument, he dug in his heels. “Instinct tells me the fragile biochemical ingredients are going to be affected by the highly excited water molecules,” he said. “You’re cooking it. If you put wine in a sautépan to bring the temperature up, people would laugh at you. What’s the difference?”

Convenience, for one thing. Efficiency for another. And one thing more.

“You get a sick feeling in the pit of your stomach, but you do these things,” Mr. Perlman said. “After all, the customer is paying for the bottle of wine.”

Now for the gory details: how to nuke a wine

There is a very simple way to bring a chilled wine up a few degrees in temperature. Let it sit at room temperature for 15 minutes. This technique, known to the ancients, produces spectacular results with minimal effort. But there are times when the harried host does not have 15 minutes. That’s where the microwave comes in, for those with the nerve to put a cherished bottle on the hot seat.

The microwave moment presents itself more frequently than one might think. True, most people do not have wine cellars, and therefore their wine is more likely to need chilling than warming. They do, however, have refrigerators. The red wine that was left to cool off a bit can come out cold, and white wine is almost certainly well below cellar temperature after several hours on the shelf. This is not a good thing. Cold helps mask the deficiencies of a white wine, accentuating its crispness and thirst-quenching properties, but it kills the taste of a complex white. Enter, to boos and hisses, the microwave oven.

Before enlisting its help, remove the metal cap from the top of the bottle and discard. It is not necessary to remove the cork, since warming the wine a few degrees will not significantly expand the volume of air between the cork and the wine. Set the microwave on high power. Every five seconds of microwaving will elevate the wine’s temperature by two degrees. Five degrees is probably the most extreme variation anyone would want to shoot for. A big-bodied red wine should be served at 60 to 65 degrees, a complex white wine from 55 to 60 degrees, and a light, fruity red at 50 to 55 degrees. Rosés and simpler whites can be served at 45 degrees or even a little cooler. A digital thermometer inserted in the bottle neck will provide an instant progress report.

March 1999

For a Tastier Wine, the Next Trick Involves …

By HAROLD MCGEE

I have used my carbon steel knife to cut up all kinds of meats and vegetables, but I had never thought of using it to prepare wine. Not until a couple of weeks ago, when I dunked the tip of it into glasses of several reds and whites, sometimes alone, sometimes with a sterling silver spoon, a gold ring or a well-scrubbed penny. My electrical multimeter showed that these metals were stimulating the wines with a good tenth of a volt. I tingled with anticipation every time I took a sip.

My foray into altering wine flavor with knives and pennies ended in failure. But it was one small part of a fruitful inquiry in which I learned new ways to get rid of unwanted aromas, including the taint of corked wine, and what aeration can really do for wine flavor.

It all began when a colleague sent me the Wine Wand, a glass device that is said to speed the aeration of a freshly opened wine and bring it to its “peak flavor” in minutes. During his blind tasting, my colleague found that the wand seemed to soften the flavor of several wines almost as well as an hour’s decanting.

The Wine Wand is a hollow glass tube that has a large cut-glass knob at one end and contains a rattling handful of pierced faceted balls that look like costume jewelry beads. A small wand for use in a wineglass sells for $325, with a travel case. A larger version that fits in a bottle is $525, with case.

The promotional literature explains that the wand speeds aeration by means of “permanently embedded frequencies, one of them being oxygen.”

This sounds like pseudoscience, and I couldn’t imagine how a glass tube could alter the aeration of wine, apart from dragging in some air as it is inserted into the bottle or glass. Yet when I and two dinner companions compared glasses of a red and a white wine with and without the Wine Wand, we found some differences.

I soon discovered that the wand is one of several wine-enhancement devices marketed to drinkers who can’t wait for their wines to taste their best. But it doesn’t come with the weirdest explanation. That distinction belongs to a bottle collar that claims to modify a wine’s tannins. With magnets.

A couple of wine-enhancement devices simply aerate wine, just as sloshing it around in the bottle or glass would. There is a battery-powered frother, and a small glass channel that adds turbulence and air bubbles as the wine flows through it from the bottle into the glass.

More intriguing was something called the Clef du Vin, or “key to wine,” a patented French product sold in several sizes, starting with a pocket size that costs about $100. It consists of a quarter-inch disc of copper alloyed with small amounts of silver and gold, embedded in a thin stainless-steel plate. The user is directed to dip the disc briefly into a glass of wine. A dip lasting one second is said to have the same effect as one year of cellar aging.

Copper, silver and gold are all known to react directly with the sulfur compounds found in wine. Copper (and the iron in my knife) also catalyzes the reaction of oxygen with many molecules. Slow oxidation in the bottle is known to cause the tannins in aged red wines to become less astringent, and it’s widely believed that aerating a young red, for example by decanting it, promotes rapid oxidation and softens its tannins.

Maybe this Clef was something more than a gimmick.

To help me evaluate the Wand, the Clef and the whole idea of enhancing freshly opened wine, I called on two friends, Andrew Waterhouse and Darrell Corti. Mr. Waterhouse is a professor of wine chemistry at the University of California, Davis, and a specialist in oxidation reactions and phenolic substances, including tannins. Mr. Corti is the proprietor of Corti Brothers grocery in Sacramento, one of the most influential wine retailers in California, and a recent inductee into the Vintners Hall of Fame.

We met at Mr. Corti’s house for an afternoon of taste tests, lunch and discussion. Some tests were blind, others open-eyed. By the end, we had indeed detected some differences between carafes and glasses of wine that were treated with the Wand or the Clef, and the wines that were left alone. The differences were not great, and not always in favor of the treated wine, which usually seemed to be missing something.

Mr. Corti said: “There do seem to be differences. The question is, are they important differences? You could buy a lot of good wine for the price of that wand.”

He also pointed out that the Clef is a very expensive version of the copper pennies that home vintners have long dipped into wine to remove the cooked-egg smell of excess hydrogen sulfide.

Mr. Waterhouse thought the elimination of sulfur aromas is all that these accessories—or, for that matter, aeration—had to offer.

“A number of sulfur compounds are present in wine in traces and have an impact on flavor because they’re very potent,” he said. “Some are unpleasant and some contribute to a wine’s complexity. You can certainly dispose of these in five minutes with a little oxygen and a small area of metal catalyst to speed the reactions up, and change your impression of the wine.”

But Mr. Waterhouse maintained that no brief treatment could convert the tannins to less astringent, softer forms, not even an hour in a decanter.

“You can saturate a wine with oxygen by sloshing it into a decanter, but then the oxygen just sits there,” he said. “It reacts very slowly. To change the tannins perceptibly in an hour, you would have to hit the wine with pure oxygen, high pressure and temperature, and powdered iron with a huge catalytic surface area.”

So why do people think decanting softens a wine’s astringency?

“I think that this impression of softening comes from the loss of the unpleasant sulfur compounds, which reduces our overall perception of harshness,” Mr. Waterhouse said.

With devices debunked and aeration unmasked as simple subtraction, the conversation turned to genuinely useful tips for handling wine.

Mr. Waterhouse said that the obnoxious, dank flavor of a “corked” wine, which usually renders it unusable even in cooking, can be removed by pouring the wine into a bowl with a sheet of plastic wrap.

“It’s kind of messy, but very effective in just a few minutes,” he said. The culprit molecule in infected corks, 2,4,6-trichloroanisole, is chemically similar to polyethylene and sticks to the plastic.

He also counseled a relaxed approach to wine storage, which he adopted in the 1980s after moving from California to Louisiana and back.

Mr. Waterhouse had a small collection of fine wines that he kept for a few years in a New Orleans closet with no temperature control. When it came time to return to California, he thought there was no point in shipping wines that had probably been spoiled in the southern heat. So he started opening them.

“There was one bottle, I think a Concannon cabernet, that was absolutely spectacular,” he recalled. “A lot of that wine had sat in our accelerated aging system and reached perfection.

“So there’s no single optimal temperature for aging wines. I’d tell people who don’t keep wine for decades to forget about cellar temperatures. Take those big reds and put them on top of the refrigerator, the most heat-abusive place you can find, and in three years they’ll probably be at their peak.”

Mr. Corti agreed.

“Wine is like a baby,” he said. “It’s a lot hardier than people give it credit for.”

January 2009