Sharpsburg/Monocacy: Jump Off to the North

(Sharpsburg)

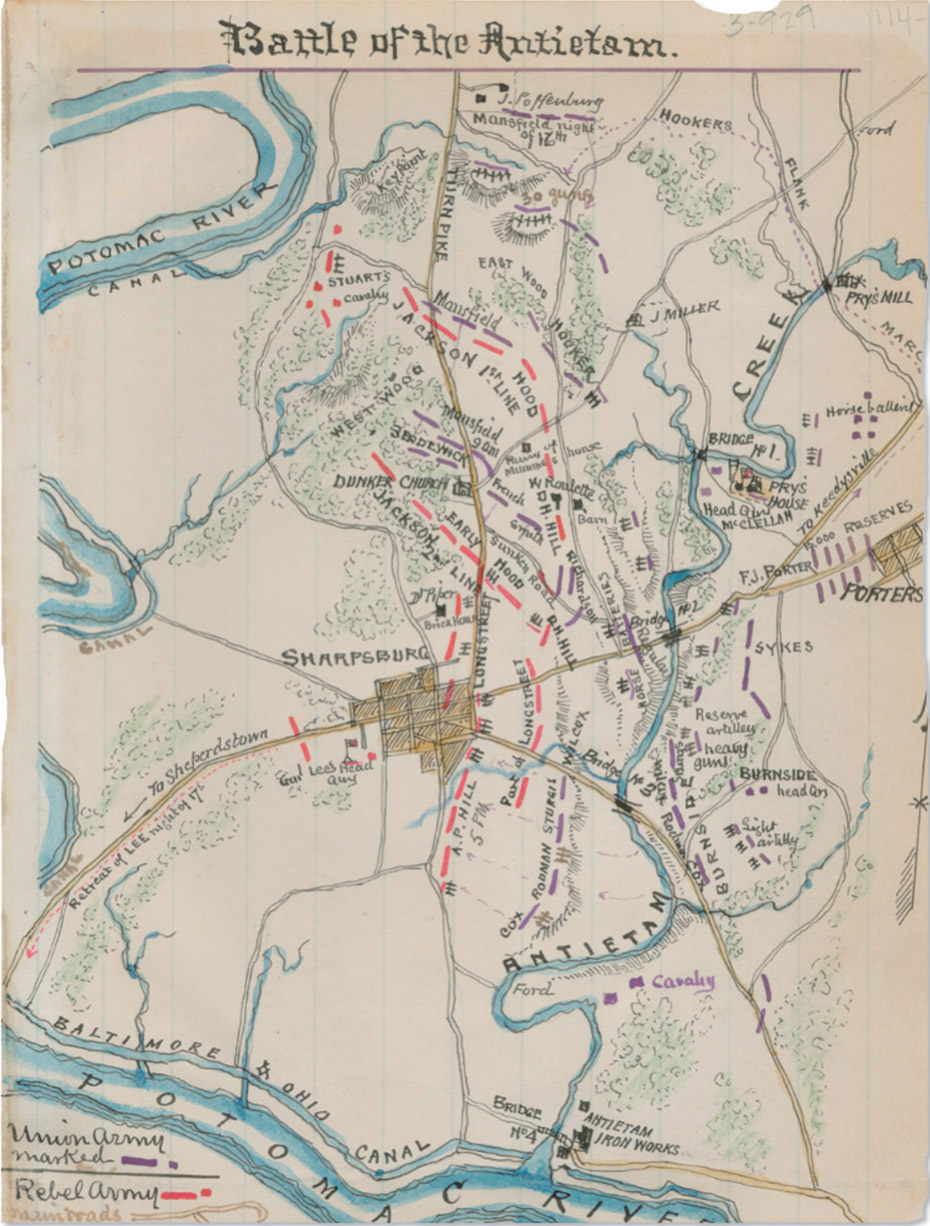

Fought between Major General George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac and General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia on September 17, 1862, the Battle of Antietam was the single bloodiest day of the Civil War. Combined casualties approached 25,000—including some 3,700 dead. The battle was a tactical draw but a strategic victory for the Federals, who forced Lee to abandon his first invasion of the North. By bringing the war to the enemy, Lee had hoped to inspire peace sentiment in the North, rally recruits to his army, and—with luck—crush the Federals in a decisive battle.

Meanwhile, the world watched. A number of European nations, particularly England, relied heavily on Southern cotton, and therefore were following the American Civil War with great interest. Confederate President Jefferson Davis hoped that a convincing Southern victory on Northern soil would bring recognition and support from the South’s trading partners overseas. Hoping to take advantage of disorganized Federal leadership in the wake of his victory in the Second Battle of Bull Run (August 29–30, 1862), Lee launched his offensive on September 4. Meanwhile, Lincoln reluctantly replaced Major General John Pope with Major General George B. McClellan—who had been removed from command of the Army of the Potomac earlier that summer. As meek as ever, McClellan told his wife that he had again been called upon to save the nation. “I only consent to take it for my country’s sake and with the humble hope that God has called me to it,” the “Young Napoleon” wrote.

Lee advanced to Frederick, Maryland, and dispatched General Thomas J. Jackson west to capture Harpers Ferry. But when the Southern commander discovered that a copy of his plans for the campaign (the famed “Special Orders No. 191”) had disappeared (a Union soldier found it, wrapped around three cigars and dropped in a vacated Confederate camp), however, he was suddenly forced to contemplate retreat. Instead, word of Jackson’s imminent return (after capturing Harpers Ferry and its entire 12,000-man Federal garrison) convinced him to fight. While Confederate units stalled Federal pursuit in the gaps of South Mountain, the balance of Lee’s infantry dug in between Antietam Creek and the town of Sharpsburg.

With a huge advantage in numbers (roughly 75,000 versus 40,000), McClellan should have—with proper coordination and judicious use of his manpower—been able to overwhelm his foe. Instead, he fought with caution and withheld support troops when they were most needed. The battle opened in the early morning fog of September 17, when elements of Union Major General Joseph Hooker’s I Corps attacked Lee’s left flank, kicking off a morning of inconclusive, bloody back-and-forth struggle through a cornfield and heavy woods. Heavy musketry mowed down soldiers and cornstalks alike—to no apparent end.

Dead soldiers in the Hagerstown Road near a cornfield after the Battle of Antietam

Meanwhile, Union General Edwin Sumner launched a poorly coordinated, two-division strike at the Confederate center, taking horrible casualties in the process. As a by-product of that misguided assault, Brigadier General William H. French found himself with some 5,700 Federals opposite a sunken road filled with a bristling line of Southerners under Brigadier General D. H. Hill. Eager to break through and divide Lee’s army, French attacked. For some three hours, Hill’s division held its ground, as the field before them filled with dead Federals and their own cart-path turned into “Bloody Lane.” Lee sent a division to support Hill. Finally, a mix-up in the Rebel line presented the Yankees with an opening: “We pressed on,” a New York infantryman later wrote, “until we reached a ditch dug in the road in which the enemy lay in line, and the few who did not surrender did not live to tell the tale of their defeat.” Shooting down the exposed Confederates “like sheep in a pen,” the New Yorkers finally opened a gap in the Rebel lines. But neither Sumner nor McClellan chose to follow up, and the hole quickly closed.

Map of the Battle of Antietam showing military positions on September 17, 1862

On the Union left, meanwhile, Ninth Corps Yankees under Major General Ambrose Burnside—the round-faced Rhode Islander whose side-whiskers would inspire the term “sideburns”—had been fighting since 10 a.m. to get across a narrow stone bridge to assail the Confederate right. Shortly after noon, McClellan—looking to break the stalemate on his right—passed word through Burnside that the bridge had to be carried at all costs. Brigadier General Samuel Sturgis assigned the job to a regiment of Pennsylvanians and one of New Yorkers, and later described the action that followed:

By the time Confederate soldiers crossed Burnside Bridge, the dramatic end of the bloodiest day in American history was approaching.

They started on their mission of death full of enthusiasm, and, taking a route less exposed than the regiments (Second Maryland and Sixth New Hampshire) which had made the effort before them, rushed at a double-quick over the slope leading to the bridge and over the bridge itself, with an impetuosity which the enemy could not resist; and the Stars and Stripes were planted on the opposite bank at 1 o’clock p.m., amid the most enthusiastic cheering from every part of the field from where they could be seen.

Having finally reached enemy ground, Burnside’s offensive lost its momentum as the Federals waited for ammunition to come up. By the time the blue lines reached the outskirts of Sharpsburg at around 3:30 p.m., Major General A. P. Hill’s 3,300 Confederates—arriving from Harpers Ferry—had reached the field to slow them. Here McClellan might have supported Burnside with reinforcements and won the day. But he did not, and the Federals paid the price. Burnside withdrew his corps back across the creek; exhaustion and the approach of dusk prevented further fighting.

Few Civil War battles matched the fight at Sharpsburg for sheer viciousness. Even Clara Barton, who would later found the American Red Cross and who had seen her share of casualties, spoke with horror as she tended to the battle’s wounded: “War is a dreadful thing. Oh, my God, can’t this civil strife be brought to an end.”

What might have—and should have—been a smashing Union victory ended instead in stalemate. While sickened Sharpsburg residents and soldiers began burying the dead, George McClellan sent only a small force in pursuit of General Lee’s retreating army. The Federals reached Blackford’s (or Boteler’s) Ford—east of Shepherdstown—on the morning of the 19th, hours after Lee’s tired troops had crossed. After a day of skirmishing, Union Major General Fitz John Porter’s Bluecoats drove off General William Pendleton’s small covering force. This inconsequential Federal pursuit ended, however, when A. P. Hill’s Rebel division counterattacked the next day. McClellan’s fate as an army commander was sealed; he hung on to his command until November, when President Lincoln relieved him in favor of Ambrose Burnside.

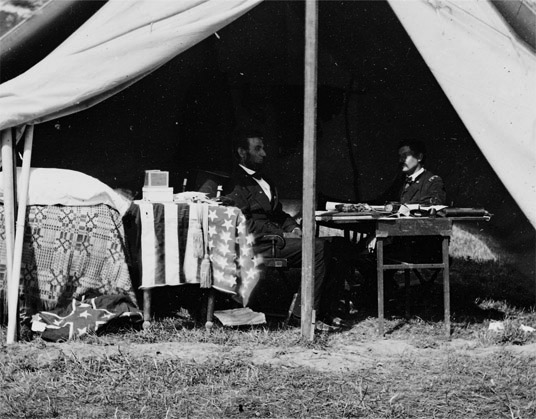

Lincoln met with General McClellan at Sharpsburg about two weeks after the battle.

While Lincoln was unsatisfied with the battle’s result, Lee had been forced to retreat south and yield the battlefield to the Union—just enough positive news to compel the president to issue his Emancipation Proclamation. Scheduled to take effect on January 1, 1863, the proclamation added a moral impetus to the political struggle and spurred the recruitment of black soldiers for the first time. The roughly 180,000 black fighting men that subsequently joined Union forces gave Lincoln—and his generals—a powerful boost against Confederate armies shrinking by the day. Lincoln would later call the Emancipation Proclamation “the central act of my administration, and the greatest event of the nineteenth century.”

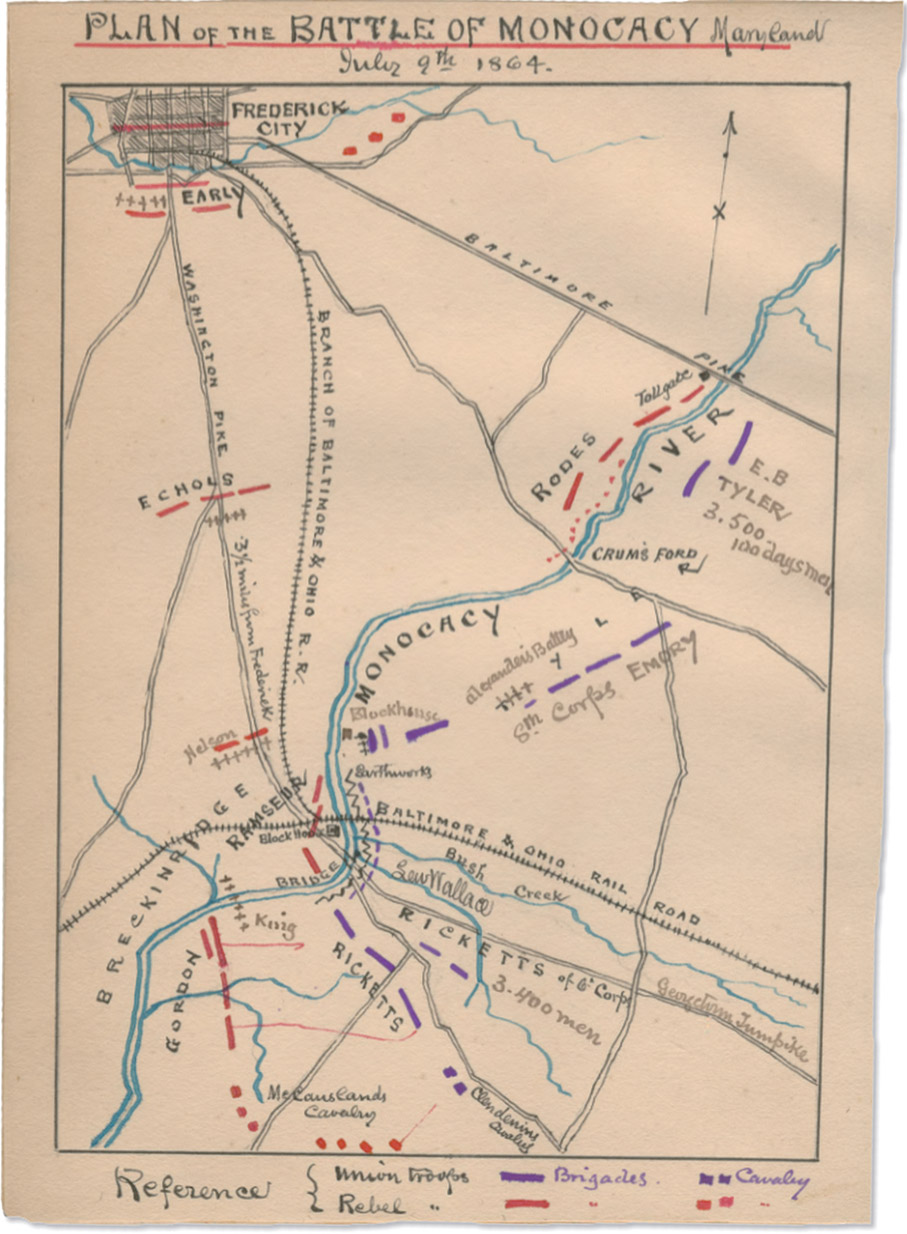

L ittle known or understood, the July 9, 1864, Battle of Monocacy bought precious time for the defenders of Washington, D.C., who were squarely in the sights of Confederate General Jubal Early.

On June 18, Early bested Union General David Hunter’s Federals at Lynchburg, ending Hunter’s scorching drive through the upper Shenandoah Valley and sending him scampering into West Virginia. Jumping at the chance for an offensive, Early gathered some 14,000 Confederate troops and marched north, reaching Winchester on July 2. By now, Early had gotten the belated attention of the War Department and the eye of General Lew Wallace. Another of the Union’s political generals, Wallace had shown flashes of potential early in the war before slipping up while commanding a division at Shiloh. Banished to the Union’s little-known Middle Department, Wallace was operating out of Baltimore when Early approached. Hoping to at least slow Early’s advance, Wallace raced west and deployed his tiny force of some 2,300 men in a strong position behind the Monocacy River, southeast of Frederick. The timely arrival of James Ricketts’s division of the VI Corps—which Ulysses S. Grant had sent north from Petersburg—still left Wallace with, at most, 5,800 troops, and outnumbered three-to-one.

On the morning of July 9, Early’s small army pushed through Frederick to find Wallace’s thin line of Federals.

Early launched a total of five assaults at the Union position before Wallace pulled his men back toward Baltimore. Early’s quick victory, however, cost him a full day—a precious 24 hours that brought Grant’s XIX Corps reinforcements closer to the capital. He reached the northern outskirts of Washington’s defensive ring on July 11, just ahead of the returning Federal VI Corps, which began filling the all-but-empty trenches around Fort Stevens.

In hindsight it seems unlikely that Early could have fought his way into Washington, even without the presence of Grant’s reinforcements. But Wallace—and many others—believed his men had saved the capital. Even Grant, whose criticism of Wallace’s performance at Shiloh had all but ruined his subordinate’s career, tossed Wallace a few accolades in his memoirs, which were published shortly after his July 1885 death. Regarding Early’s withdrawal from Washington’s doorstep, Grant offered:

Plan of the Battle of Monocacy

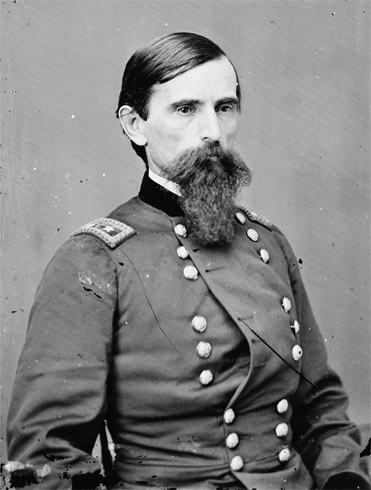

General Lew Wallace

There is no telling how much this result was contributed to by General Lew Wallace’s leading what might well be considered a forlorn hope. If Early had been but one day earlier he might have entered the capital before the arrival of the reinforcements I had sent. Whether the delay caused by the battle amounted to a day or not, General Wallace contributed on this occasion, by the defeat of the troops under him a greater benefit to the cause than often falls to the lot of a commander of an equal force to render by means of a victory.

For Wallace—who in the years following the Civil War would write the best-selling novel, Ben-Hur, negotiate with an outlaw named Billy the Kid (both while governor of New Mexico Territory), and serve as U.S. consul to Turkey—such praise must have been highly satisfying.

The Battle of Ball’s Bluff might have been dismissed as just one more of the Union’s early-war beatings if it had not claimed the life of U.S. senator—and longtime friend of President Abraham Lincoln—Edward D. Baker.

For the men in blue, the battle was especially ugly. Since the Confederate victory at Bull Run on July 21, there had been little movement in the east. Small bodies of Union and Confederate troops watched each other from their posts on either side of the Potomac River. In October, General George B. McClellan—then hard at work assembling the Army of the Potomac—suggested that Brigadier General Charles P. Stone undertake to dislodge Confederates posted at Leesburg, just west of the river. In the early-morning darkness of October 21, Stone sent three brigades (one under the command of Oregon senator Edward Baker) across the Potomac and up a muddy rise at a roughly equal force of Rebels under Brigadier General Shanks Evans.

Supporting units entered the fray after sporadic opening shots, and the two sides exchanged fire into the afternoon. At about 4 p.m. a sharpshooter’s bullet ended Baker’s life; soon after, the Federal lines bent then broke, and panicked soldiers stumbled and slid back down Ball’s Bluff. Rebel pursuers wounded scores of foundering Yankees as they tried to ford the river. Hundreds of other Federals were captured. The battle changed nothing. Evans lost 33 Confederates killed and another 116 wounded or missing. Stone’s brigades were practically halved, with 49 Yankees killed, 158 wounded (including Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.), and more than 700 captured or missing.

Once known as Mecklenburg, this West Virginia (formerly Virginia) town lent its name to the two-day clash that occurred just to its east, along the Potomac River, on September 19–20, 1862. Wounded victims of the Battle of Shepherdstown and its massive predecessor filled virtually every building in the area. At least 100 Confederates killed outside of Shepherdstown were buried in Elwood Cemetery, where some 300 Southerners—including Stonewall Jackson’s aide, Henry Kyd Douglas—now lay.

![Plan of the Battle of BALL'S BLUFF. VA Fought October 21st 1861. Copy of Official Pean. [1-279] 1-282 FARM Road Balls house field SWAMP WOODS SMART'S MILL Balls Caralry dismintets 4 cos 17th times Co K Jeniper house 3rd thissitte Booksdale Bramhalls Batters 15th Devins 8th Virsnam muntam Lane Cavalty EVANS csa 15 TH Miss burt 17 MIssp Featherstone To Edwards cenry FIELD 6 cares - to antly plonghed field branahall 1st california wistor crapt French Teunacurll Regt Gulcogssmell Col. Baket Capt French Two 14 p ch guns 1900 men 15th Mass col Devins 3 mills ROAD BALL’S Cal. Lee. 40 Mass BLUFF P 56 TO high CHESAP EAKE AND OMIO CANAL 100 Yas 19th-Mass house HARRISONS ISLAND honst 400 AGRES Retreat Ctussing POTOMAC CANAL 200 yds OH10 bills troup gussed here Geril strong row house Road Union forces Rebel forces](../Images/chpt_fig_009.jpg)

Map of the Battle of Ball’s Bluff

Today, visitors can walk through the cemetery as part of a day spent in town, which has been named a Historic District in the National Register of Historic Places. Shepherdstown is also the home of the George Tyler Moore Center for the Study of the Civil War. Founded in 1993, the center is now located on German Street in the Conrad Shindler House, one of countless town buildings that served as makeshift hospitals following the Battle of Antietam. The house was purchased by actress Mary Tyler Moore and donated to then-Shepherd College in 1996, as a tribute to her father George Tyler Moore, a Civil War enthusiast. For information on the center and its programs, call (304) 876-5429.

History enthusiasts will also want to visit the Historic Shepherdstown Museum, at the corner of Princess and East German Streets. Set in the restored Entler Hotel, a two-story brick holdover from the Civil War era, the museum boasts several rooms, a re-creation of a Victorian sitting room, a 1905 mail wagon, and a number of American Indian and Civil War artifacts and exhibits, among other items. The museum is open April through October. Admission is free. Further information about the museum and historic downtown Shepherdstown can be found at www.historicshepherdstown.com.

Antietam National Battlefield

5831 Dunker Church Rd.

Sharpsburg

(301) 432-5124

www.nps.gov/anti

Today, the serene landscape of Antietam National Battlefield looks much as it did when the battle began. In recent years, the park has reacquired about 2,000 acres of the battlefield’s original countryside, reforested its west and north woods, added some 8,000 feet of historically accurate fencing, and refurbished several of the park’s original structures. In addition to 2½ miles of new park trails and a renovated visitor center and museum, the park is now also home to the Pry House Field Hospital Museum, an extension of the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, in Frederick. General McClellan made the house the headquarters of his Union forces, which was visited by Abraham Lincoln two weeks after the battle. Facilities are wheelchair-accessible. Located off Route 65, the park is easily accessible from any direction.

Antietam National Cemetery

Antietam National Battlefield

5831 Dunker Church Rd.

Sharpsburg

(301) 432-5124

www.nps.gov/anti

The final resting place for 4,776 Union soldiers who were killed in the battles of Antietam, Monocacy, and in other nearby conflicts, Antietam National Cemetery is now one of the 130 cemeteries that make up the National Cemetery System. At the center of the cemetery stands a 44-foot, 7-inch granite statue of a Union infantryman, facing homeward to the north to commemorate the fallen soldiers.

Ball’s Bluff Battlefield and National Cemetery

Rte. 15 at Battlefield Parkway

Leesburg, VA

(703) 779-9372

www.nps.gov/nr/travel/journey/bnc.htm

Although Ball’s Bluff is located in Virginia, it’s just a quick drive down Route 15 from Frederick. Surrounded—much like Manassas Battlefield—by the trappings of the modern world (one must drive through a residential development to reach it), Ball’s Bluff Battlefield and National Cemetery is nevertheless nicely tucked away in dense woods. A ¾-mile walking path takes visitors from the parking lot to the edge of the steep bluff down which Union troops fled at battle’s end. Aside from the steep hill itself, the highlight of the battlefield is its National Cemetery, a neatly groomed, walled-in burial site containing 25 graves representing 54 of the battle’s victims. Only one of these men—James Allen of the 15th Massachusetts—has been identified. Admission is free.

Barbara Fritchie House and Museum

154 W. Patrick St.

Frederick, MD

(301) 698-8992

Barbara Fritchie was immortalized in a John Greenleaf Whittier poem as the woman who challenged Confederate troops in the streets of Frederick: “Shoot if you must, this old gray head,” Fritchie reportedly shouted from an upstairs window, “but spare your country’s flag.” This reconstruction of Fritchie’s original house is open for tours by appointment.

The Kennedy Farmhouse (John Brown’s Headquarters)

2406 Chestnut Grove Rd.

Sharpsburg

(202) 537-8900 (tour information)

www.johnbrown.org

Located just 6 miles from Harpers Ferry, this small farm proved to be just what John Brown needed when he went house hunting in 1859. Under the alias “Isaac Smith,” Brown lived here with his followers as they prepared for their 1859 campaign to free slaves. With the help of federal funds and private donations, co-owner South Lynn spent some 20 painstaking years restoring the old farmhouse to its original appearance. Despite the historic significance of the building, which has been declared a National Historic Landmark, its maintenance and operation (still looked over by Mr. Lynn) depends on public support.

Monocacy National Battlefield

4801 Urbana Pike

Frederick, MD

(301) 662-3515

www.nps.gov/mono

The Monocacy National Battlefield Park opened a new 7,000-square-foot visitor center in 2007, transforming the occasionally overlooked park into a compelling experience for Civil War enthusiasts who want to explore the “battle that saved Washington.” In addition to the new exhibits and electronic maps, the park also opened four new walking trails, making acres of the historic grounds more accessible to the public. A self-guided driving tour follows the events of July 9, 1864. Admission is free.

Mount Olivet Cemetery

515 S. Market St.

Frederick, MD

(301) 662-1164

www.mountolivetcemeteryinc.com

Francis Scott Key, Barbara Fritchie, Maryland’s first governor, Thomas Johnson, and some 800 Union and Confederate soldiers lie in Mount Olivet Cemetery, which is open from dawn to dusk daily.

National Museum of Civil War Medicine

48 E. Patrick St.

Frederick, MD

(301) 695-1864

www.civilwarmed.org

The vastness of Civil War battlefields and the study of regiments, corps, and flanking movements can easily make one forget about war’s human cost. For that reason alone, the National Museum of Civil War Medicine is one of those places that everyone—not just Civil War enthusiasts—should visit. The museum, which opened in 1996, filled a huge void in the field, and has since added a satellite building (the Pry House Field Hospital Museum) on the Antietam Battlefield.

Installed in 7,000 square feet of space on two floors are lifelike displays that tell the story of Civil War medicine. Boasting an unmatched collection of medical artifacts, they cover the role of the surgeon, from his own sparse training through the examination of recruits (usually superficial); the dangers of camp life (an exhibit that contains the war’s only known surviving surgeon’s tent); field-dressing and battlefield care; nursing; and a new exhibit on the embalming of the dead.

The National Museum of Civil War Medicine is wheelchair accessible. It also offers group tours, which take about 90 minutes and should be arranged in advance. The museum boasts a research room and a one-of-a-kind gift shop.

Rose Hill Cemetery

(301) 739-3630

600 S. Potomac St.

Hagerstown, MD

www.rosehillcemeteryofhagerstown.org

In the decade that followed the Civil War, some 2,000 Confederate soldiers killed at Antietam or South Mountain were reinterred here. Only 346 of the men were ever identified.

South Mountain State Battlefield

6620 Zittlestown Rd.

Middletown, MD

(301) 791-4767

www.dnr.state.md.us

Part of the South Mountain Recreation Area, the site of the September 14, 1862, Battle of South Mountain is now maintained and operated by the nonprofit group Friends of South Mountain State Battlefield. Only the key sections of the park—Turner’s Gap, Fox’s Gap, and Crampton’s Gap—currently feature roadside markers, interpretive signage, or monuments. But with some financial assistance, the group hopes to add museums at the north and south ends of the battlefield.

| Hill House Bed & Breakfast 12 W. Third St. Frederick, MD (301) 682-4111 www.hillhousefrederick.com |

$$$–$$$$ |

This circa-1870 restored Victorian town house is a great place to stay if you’re looking for easy access to downtown Frederick’s antiques shops and historical sites. The impeccably restored inn boasts four guest rooms furnished with original art, antiques, and period accents like four-poster and canopy beds. Guests also enjoy private bathrooms and a full southern Maryland breakfast each morning.

| Hollerstown Hill 4 Clarke Place Frederick, MD (301) 228-3630 www.hollerstownhill.com |

$$$ |

Staying at Hollerstown Hill is much like staying in a doll-house. Tucked away in a quiet Frederick neighborhood, the circa-1900 Victorian even boasts its own collection of antique dolls, tastefully displayed around the house in the company of other period antiques. There are four large guest rooms, each with wireless Internet, private bath, and one with its own private porch. After a busy day of sightseeing, you can wage battles of your own in a game room stocked with board games, a pool table, and even a Civil War chess set.

| The Inn at Antietam Bed and Breakfast 220 E. Main St. Sharpsburg (301) 432-6601 www.innatantietam.com |

$$$–$$$$ |

Few people get the chance to sleep in such comfort on a Civil War battle site, especially one as important as Antietam National Battlefield. But that’s just what the Inn at Antietam Bed and Breakfast offers in five distinct suites that range in price and degree of luxury. Each suite features central air-conditioning, private baths, and old-time comfort. Others (such as the General Burnside Smokehouse Suite) also offer a fireplace, wet bar, and TV/VCR. Common areas include a small library, a parlor (with a baby grand piano), a solarium, and a wraparound porch from which residents can take in the area’s unmatched scenery.

| Inn at Buckeystown 3521 and 3619 Buckeystown Pike Buckeystown, MD (301) 874-5755 www.innatbuckeystown.com |

$$$–$$$$ |

Just south of Monocacy, this award-winning inn offers a central location from which to explore Antietam, Frederick, Harpers Ferry, and northern Virginia. Built in 1897, the historic mansion was converted to a luxurious five-bedroom guesthouse in 1981. In the rooms, you’ll find sparkling chandeliers (and even working fireplaces in three of the rooms), plus glorious gardens and a wraparound porch that’s perfect for savoring a glass of wine (it’s strictly bring-your-own-bottle, so be sure to stop by a local winery on your way). For a late-afternoon pick-me-up, the inn also offers a delightful high tea service.

| Jacob Rohrbach Inn 138 W. Main St. Sharpsburg (301) 432-5079 (877) 839-4242 www.jacob-rohrbach-inn.com |

$$$–$$$$ |

The Jacob Rohrbach Inn is a historical treasure, built more than 50 years before the outbreak of the Civil War. The five-bedroom inn lies within walking distance of the battlefield park and even stocks bicycles for guests who wish to explore the park on two wheels. Before you set out for the day, feast on a delicious multicourse breakfast, prepared with herbs and produce grown on the property. Although the house itself is more than 200 years old, it boasts a full suite of modern amenities like wireless Internet and cable TV, and owners Joanne and Paul Breitenbach are eager to assist with historical information, along with recommendations for sightseeing and entertainment.

| Thomas Shepherd Bed and Breakfast Corner of Duke and German Sts. Shepherdstown, WV (888) 889-8952 www.thomasshepherdinn.com |

$$$–$$$$ |

Those who take the quick 4-mile drive from Sharpsburg to Shepherdstown will find comfortable accommodations at the Thomas Shepherd Inn, which happens to be the only bed-and-breakfast in town. Built in 1868, the Federal-style inn is one of the few buildings in town that was not used as a hospital following the Battle of Antietam.

Located at the end of Shepherdstown’s main thoroughfare, the Thomas Shepherd Inn offers convenience (within walking distance of everything in town, and driving distance of Harpers Ferry, etc.), comfort (six delightful, air-conditioned rooms, private baths), friendly service (homemade breakfast served each morning, etc.), and—considering that owners Jim Ford and Jeanne Muir have Shepherdstown’s B&B market cornered—surprisingly reasonable prices.

| Blue Moon Café Corner of Princess and High Sts. Shepherdstown, WV (304) 876-1920 www.bluemoonshepherdstown.com |

$$ |

The Blue Moon menu boasts just about every American staple one can imagine, including gourmet pizzas, fine dinners, hearty sandwiches and salads, and vegetarian meals. You’ll take a trip around the globe just by perusing the menu: vegan chickpea curry is listed on the same page as “Jessie’s Meato Escondido,” a roast beef sandwich topped with feta cheese, fresh spinach, onions, and cucumbers, served on ciabatta bread slathered with herbed cream cheese. The casual environment is just as diverse, with seating in three different dining rooms and outside along the water.

| Cacique 26 N. Market St. Frederick, MD (301) 695-2756 www.caciquefrederick.com |

$$ |

You might not think that Frederick would be a hotbed for haute cuisine, but the town has practically become a suburb of Washington, D.C., and it’s attracted its share of residents with sophisticated palates. At Cacique, Spanish and Mexican cuisine sit side by side—a cultural faux pas, perhaps, but diners give a thumb’s-up to Spanish dishes like paella or mussels prepared in Andalucian fashion, as well as traditional Mexican cuisine.

| Captain Bender’s Tavern 111 E. Main St. Sharpsburg (301) 432-5813 www.captainbenders.com |

$$ |

Captain Bender’s is a great local gathering place. It’s named for Raleigh Bender, a boatsman on the C&O Canal in the nineteenth century, who also managed a tavern on the site of his modern-day namesake. You can always count on a cold beer, a thick burger, or a generous salad, plus an assortment of panini and pizzas. The restaurant even appeals to heartier appetites with the “death dog,” a foot-long hot dog topped with chili, cheese, diced onion, and sour cream.

| The Cozy Restaurant 103 Frederick Rd. Thurmont, MD (301) 271-4301 (inn) (301) 271-7373 (restaurant) www.cozyvillage.com |

$$ |

Part of the historic Cozy Inn, the Cozy Restaurant is the oldest family-owned restaurant in Maryland, established in 1929. It’s a good choice for groups, specializing in fine American dining in its 11 uniquely styled rooms, in addition to lavish buffet dinners and fantastic baskets of food to go. There’s also a pub serving traditional bar food and Willy’s Beer, prepared especially for the inn. It’s just a few short miles from the famous presidential retreat at Camp David, and there’s a museum on-site stocked with gifts from members of the press and visiting dignitaries.

| Jennifer’s 207 W. Patrick St. Frederick, MD (301) 662-0373 http://pages.frederick.com/dining/jennifers |

$$ |

There’s something friendly and inviting about this Frederick pub, a mainstay for more than two decades. A popular draw for locals, Jennifer’s decor is cozy and inviting; exposed brick walls, a large oak bar, and even a fireplace. For lunch, sample salads, sandwiches, or pizza, while dinner brings tasty creations like hot and crunchy chicken with honey-pecan butter or lamb chops. The restaurant also offers a spa menu for light eaters.

| Monocacy Crossing 4424A Urbana Pike Frederick, MD (301) 846-4204 www.monocacycrossing.com |

$$$ |

If you feel like dining off the beaten path, you won’t be disappointed with Monocacy Crossing. One of Frederick’s top-rated restaurants, it delivers with fantastic food, attentive service, a well-thought-out wine list, and a gorgeous setting. Seafood creations like steamed mussels and clam chowder are fresh and perfectly seasoned, or sample the season’s bounty with creations like the Eggplant Napoleon, with layers of fried slices of eggplant, roasted peppers, zucchini, and mushrooms, topped with marinara sauce. On a pleasant day, sit on the outdoor patio to dine alfresco.

| The Tasting Room 101 N. Market St. Frederick, MD (240) 379-7772 www.tastetr.com |

$$$ |

As Frederick’s first wine bar, The Tasting Room touts the most extensive, diverse wine list in Frederick—and in most of the D.C. exurbs—along with chic decor that’s clearly designed with the young professional set in mind. Located on the corner of Church and Market Streets in downtown Frederick’s restaurant district, the stylish restaurant and its patrons look like they’d feel right at home in Manhattan. (Even if you don’t dine here, you can peer inside through its floor-to-ceiling windows.) Cosmopolitan flavors also take center stage on the menu prepared by chef and owner Michael Tauraso. Select from starters like Greek lamb, bruschetta, or tuna crudo with sesame-lime dressing, then go for a sophisticated entree like the Kobe-style Berkshire pork loin, crusted with a blend of coriander and pepper, or local rockfish.