Harpers Ferry/Winchester: Into the Valley

“Harpers Ferry,” Indiana corporal Edmund Brown wrote after the war, “was a fitting place to begin an advance against the rebellion.”

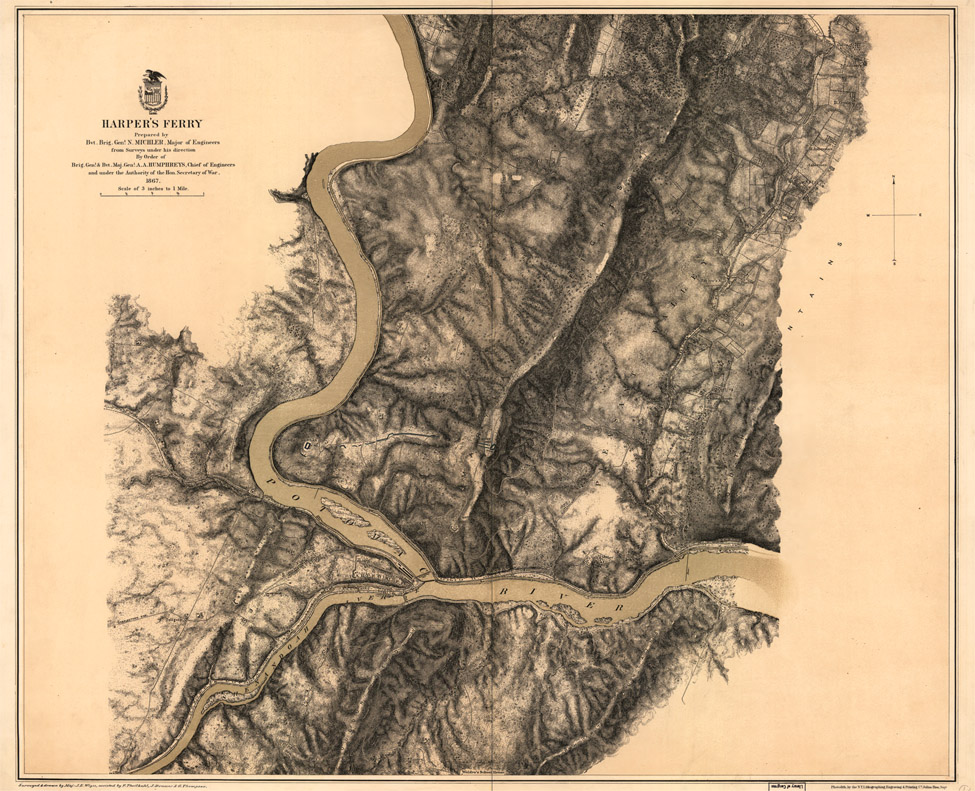

There was no doubting the area’s strategic importance, located as it was on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad line at the gateway to the vital Shenandoah Valley—a natural north-south invasion route packed with forage for man and beast. It was a town worth fighting for, even after Confederate soldiers burned its Federal arsenal and armory and dragged off its valuable gun-making machinery early in the Civil War. The town would change hands at least eight times before Major General Philip Sheridan finally secured it for the Union in 1864. By then, its once-vital armory was a blackened brick shell of its former self—almost, but not quite, lost to history.

Until October 1859, this small town located at the confluence of the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers was known simply as the home of the historic, old arsenal, and for the stunning natural beauty that surrounded it. By then, “the Hole,” as the site was first known, had its first European residents and its namesake business—a ferry service across the Potomac operated by Philadelphian Robert Harper. Authorized by President George Washington, the Harpers Ferry Arsenal opened in 1801, joining the U.S. Armory at Springfield, Massachusetts, in producing arms for the young American military. In 60 years of production, Harpers Ferry machinery turned out some 600,000 guns—including the Model 1803 flintlock and the Model 1841 percussion rifle, the nation’s first. Meanwhile, sectionalism and the slavery issue tore at the United States until a grim, old Westerner marched east to transform a town and a nation.

A cold mist swirled through Harpers Ferry in the evening darkness of October 16, 1859. Outside the brick buildings of the U.S. Armory, a lone sentry named Daniel Whelan paced, unaware that revolution was unfolding in the flickering blackness around him.

In the blink of an eye, it seemed, a motley group of armed men had surrounded the startled Whelan, taken him prisoner, and forced their way into the Federal compound he guarded. Whelan listened in stunned silence as the gray-bearded leader of his assailants stepped forward and announced his presence before his god.

“I come here from Kansas,” John Brown declared, “and this is a slave state; I have possession of the United States armory, and if the citizens interfere with me, I must only burn the town and have blood.”

Thus began Kansas abolitionist John Brown’s first step in his mission to free America’s slaves. Harpers Ferry would thenceforth forever be linked—depending on one’s viewpoint—with violent abolitionist extremism or with the American slave’s fight for freedom.

Brown’s long-planned assault on slavery was doomed almost from the start. Leading an invasion force of just 21 men, Brown had pinned his hopes for reinforcement on slaves and free blacks in the area. His raid was to be the spark that ignited a massive slave rebellion and brought about the end of the “peculiar institution.” Having armed his new recruits from his own arms stores, Brown would lead them into surrounding hills to begin a guerrilla war.

None of this would happen, a fact that grizzled old “Osawatomie Brown” may have recognized after two of his minions shot and mortally wounded Shepherd Hayward—a free black employed by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. Hayward, who, out of curiosity, had stepped off a B&O train as it stopped on the edge of town, was shot in the back as he tried to avoid two armed strangers in the early-morning darkness of October 17.

Very little else went right for Brown’s “Army of Liberation.” Men dispatched to spread word of the operation and recruit volunteers returned with just a handful of mostly reluctant and confused slaves and their masters, now Brown’s prisoners. The sun slowly rose as Brown waited in vain for the legions of black volunteers to appear, and as word of the raid spread. By early morning, hundreds of irate Virginians had converged on the village, guns in hand, eager to deal with the hated abolitionist invaders. Gunfire erupted; three locals fell dead, along with eight of Brown’s men. Brown—now more or less trapped in the arsenal’s engine room—tried unsuccessfully to negotiate for passage out of town in exchange for his hostages. No one was listening.

Map of Harpers Ferry illustrating its strategic importance on the Potomac River

At dawn on October 18, Lieutenant J. E. B. Stuart delivered to Brown a surrender request from his superior, Colonel Robert E. Lee, who had reached the site during the night with a contingent of U.S. Marines. Brown refused; marines subsequently rushed the engine house, knocked down its doors, and captured what was left of Brown’s army. A handful of marines were wounded during the struggle, as was the elder Brown. One of Brown’s sons was dead; a second was mortally wounded.

In a November 23 letter to a Reverend McFarland, Brown wrote:

Christ told me to remember them that were in bonds as bound with them, to do towards them as I would wish them to do towards me in similar circumstances. My conscience bade me do that. I tried to do it, but failed. Therefore I have no regret on that score. I have no sorrow either as to the result, only for my poor wife and children. They have suffered much, and it is hard to leave them uncared for. But God will be a husband to the widow and a father to the fatherless.

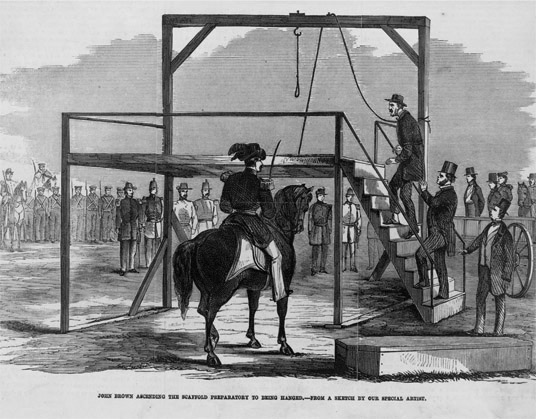

After a whirlwind trial through which the injured defendant remained prone on a cot, Brown was convicted of treason and murder, and was sentenced to hang.

On December 2, 1859, John Brown rode to his death sitting atop his own coffin in the back of a wagon. A brand new gallows—surrounded by 800 armed men, reporters, and curious eyewitnesses—awaited him. Without fear or apprehension, Brown mounted the gallows, and, a few minutes later, dropped to his death.

John Brown walks to his death.

The approach of the Civil War magnified Harpers Ferry’s importance—and its vulnerability. Dominated by high ground on three sides, it was practically indefensible.

On April 17, 1861—just three days into the war—an approaching force of Virginia militia and volunteers compelled Lieutenant Roger Jones to set the armory afire and evacuate his tiny Federal garrison. Southern troops arrived too late to claim some 15,000 rifles from the flames, but they managed to save the machinery that turned the guns out. This they shipped to Richmond, where it was soon put to use arming Confederates.

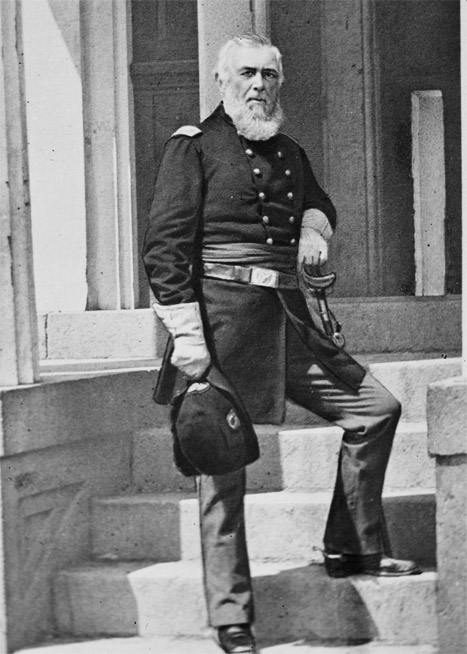

Harpers Ferry was back in Federal hands in September 1862, when Confederate general Robert E. Lee launched his first invasion of the North. Looking to open a supply route through the Shenandoah Valley, Lee sent Stonewall Jackson west to remove the one impediment to his plan—a Yankee garrison at Harpers Ferry, now 12,500 men strong. Charged with holding the town to the last extremity was 58-year-old Union colonel Dixon Miles, a gray-bearded, elderly looking, army lifer whom events would soon prove had been caught in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Colonel Dixon Miles

Jackson—who had spent the summer defeating Union armies throughout the Shenandoah Valley—sent one column under General John Walker to take Loudoun Heights, and another under General Lafayette McLaws to deal with Federal defenders on Maryland Heights. Jackson would complete the encirclement by occupying Bolivar Heights, in the arsenal’s rear.

The issue was only briefly in doubt. Walker quickly accomplished his task. McLaws’s Confederates somehow managed to haul cannon and ammunition up Maryland Heights, where, on the morning of September 14, they faced off against Colonel Thomas Ford’s 1,600 Bluecoats. Ford’s artillerists held their own against McLaws’s gunners, but his green infantry—many of whom had not yet mastered even the basics of soldiering—soon broke before the hardened Rebels. The shaken Union soldiers raced back over the Potomac and into town, ceding the heights—and, unwittingly, victory—to Jackson.

Jackson’s forces opened fire and quickly forced a Union surrender. Some 1,300 Union cavalrymen managed to escape the trap, but Jackson captured everyone and everything else, including 13,000 rifles and 70 cannon. Jackson’s hard-driving foot soldiers impressed their captives: “They were silent as ghosts,” one Yankee recalled, “ruthless and rushing in their speed; ragged, earth colored, disheveled and devilish, as tho’ they were keen on the scent of the hot blood that was already streaming up from the opening struggle at Antietam, and thirsting for it.”

The town changed hands several times prior to the summer of 1864, when Union major general Philip Sheridan finally secured the Shenandoah Valley for the Union. But by then the once-prized arsenal and armory was little more than burned-out brick and mortar, valueless, save for posterity.

For the residents of Winchester, Virginia, any day that passed without the rattle of muskets or the thundering hoofbeats of passing cavalry was a gift. Laid out at the northern end of the Shenandoah Valley, it stood in the way of Union and Confederate armies traveling up or down the Valley Pike, or rumbling off on one of the several other roadways that passed through town. It was also home to a Baltimore and Ohio Railroad terminal. Due to its importance as a transportation hub, this small town of 4,500 changed hands more than seventy times in four years of war, and witnessed three significant Civil War battles. It was the seat of hearty Confederate support, especially after Stonewall Jackson made the town the headquarters of his Shenandoah Valley District in November 1861.

In the spring of 1862, George McClellan’s Army of the Potomac trudged slowly up the Virginia Peninsula, moving inexorably toward the Confederate capital of Richmond. While Albert Sidney Johnston and then Robert E. Lee dealt with McClellan, Stonewall Jackson was left to prevent Union forces in the Shenandoah Valley from slipping west to reinforce the Yankee commander. After chasing John C. Fremont out of the valley, Jackson moved north in pursuit of Nathaniel Banks’s Union army. On May 23, Jackson’s men overran a small Federal force at Front Royal; two days later, Jackson assaulted Banks’s army in the hills south of Winchester. Withstanding fierce resistance and devastating Federal artillery fire, Jackson sent Banks’s army retreating through the town and north across the Potomac.

Even worse results befell Union major general Robert H. Milroy a year later, during Lee’s second invasion of the North. Dismissing reports of Lee’s rapid advance, Milroy waited until his garrison at Winchester was almost completely encircled. By the time he ordered a withdrawal, Richard Ewell’s Corps was on hand to cut off his retreat and sweep up prisoners.

Confederate forces in the Shenandoah Valley continued to plague the Union until August 1864, when Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant—now in overall command of Union armies—sent Major General Philip Sheridan to eliminate the problem. Sheridan was a born fighter—aggressive and opportunistic—and he hustled his 40,000-man Army of the Shenandoah into the valley in pursuit of General Jubal Early’s audacious little Army of the Valley, which had threatened Washington a few weeks earlier. On September 19, Sheridan’s 37,000 Federals attacked Early’s 17,000, dug-in troops east of Winchester, slamming into the Confederate center and Early’s left. After an afternoon of fighting, Union cavalry from the north and infantry from the east forced Early into retreating south down the pike to Strasburg. After losing again to Sheridan two days later at Fisher’s Hill, Early—and the Confederates—were all but finished in the valley.

Sheridan after the Battle of Winchester, September 1864

Harpers Ferry National Historical Park

Rte. 340

Harpers Ferry

(304) 535-6029

Visiting Harpers Ferry today is like taking a step back in time; it is a place that every American should see. Only the small engine house building in which John Brown made his last stand in 1859 (now known as John Brown’s Fort) remains from the old arsenal.

Little sign remains of the army garrisons (usually Union) that were once stationed here, first to protect the arsenal and then to protect the Ohio and Baltimore Railroad that ran through town. But despite what has been lost, the town (only part of which is owned by the National Park Service) remains very much a 19th-century settlement. A house built by Robert Harper, who established a ferry service here in 1761, still stands in the lower town. Antiques and gift shops and restaurants line the quaint streets, along with historic buildings and museums. Depending on the season, costumed interpreters are on hand for demonstrations and to answer questions.

Visitors should begin their visit at the Cavalier Heights Visitor Center (which houses a small gift shop and restroom facilities), where they can park and board buses into town.

The buses are wheelchair-accessible and leave every 15 minutes. Book hounds will want to stop by the Park’s Bookshop on Shenandoah Street, in the lower part of town. At nearly 3,800 beautiful acres—unhindered by the urban sprawl that threatens other parks—Harpers Ferry National Historical Park also features a number of beautiful hiking trails through the hills above town; maps for these can be found online and at the visitor center. The park also contains a library and research room, which is open by appointment.

Jefferson County Museum

200 E. Washington St.

Charles Town, WV

(304) 725-8628

Jefferson County is proud of its Civil War heritage, and with good reason. While still part of Virginia, the county provided more troops to the Confederate cause than any other locality except for Richmond. Despite its Southern sympathies, Charles Town was also the hometown of Martin Delany, the highest-ranking African-American officer during the Civil War. The museum’s most prized Civil War relic is the flag that once flew with J. E. B. Stuart’s Horse Artillery. The museum is open Apr through Nov.

John Brown Gallows Site

515 S. Samuel St.

Charles Town, WV

Under the sunny, late-morning sky of December 2, 1859, a crowd of reporters, curious onlookers, and soldiers gathered in a field to witness the final moments of John Brown—the Kansas abolitionist whose raid on Harpers Ferry had further polarized a nation. Today, a private home occupies the ground on which Brown went to the gallows. But although only a historical marker outside that property remains to explain what took place on the site, it remains a solemn place worth visiting. The Jefferson County Courthouse, where Brown was tried, is also located close by.

John Brown Wax Museum

168 High St.

Harpers Ferry

(304) 535-6342

It’s hard to miss the John Brown Wax Museum, and visitors to the town definitely should not. The museum’s wax figures of Brown, his followers, and the marines sent in to arrest them are eerily human, especially considering how near Brown’s party once was to this site. The museum is open from mid-Mar through mid-Dec.

Civil War Orientation Center

20 S. Cameron St.

Winchester, VA

(540) 535-3543

If you’re planning to explore the Civil War sites of the Shenandoah Valley, this Orientation Center and interactive Web site will help you plan your route. Visit online at home to gather information and ideas, and then stop by the Orientation Center as you start your journey.

Fort Collier Civil War Center

922 Martinsburg Pike

Winchester, VA

(540) 662-2281

In 1861, Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston ordered the construction of a series of defensive earthworks around Winchester, at the northern end of the Shenandoah Valley. For three years they remained unused, until September 19, 1864, when hundreds of Union cavalrymen stormed the Confederate-filled works north of town, all but ending the Third Battle of Winchester. These fortifications—known as Fort Collier—remain a sight to see. The site is open dawn to dusk.

Kernstown Battlefield

610 Battle Park Dr.

Winchester, VA

(540) 869-2896

Now a registered National Historical Landmark, this site of two Civil War clashes (in 1862 and 1864) is now being looked after by the Kernstown Battlefield Association. Ongoing preservation efforts have led to the purchase of more than 300 acres of the battle area and the addition of road markers and interpretive signage. A small visitor center is open on weekends from May through Oct. Admission is free.

Museum of the Shenandoah Valley

901 Amherst St.

Winchester, VA (202) 662-1473

This beautiful new $20 million museum opened in 2005 to tell the story of the culture and history of the Shenandoah Valley. While the Civil War isn’t a primary focal point of the curriculum, it’s worth a visit for anyone who’s planning to explore the region in-depth. Admission varies depending on which tours you take.

Old Court House Civil War Museum

20 N. Loudoun St.

Winchester, VA

(540) 542-1145

Built in 1840 and used as a hospital and prison during the Civil War, this building served Frederick County until 1995; in 2003 it reopened to the public as a small but interesting museum with exhibits that feature some 3,000 objects. Located in the heart of Winchester’s Old Town Walking Mall, it is definitely worth a look.

Stonewall Jackson’s Headquarters Museum

415 N. Braddock St.

Winchester, VA

(540) 667-3242

www.winchesterhistory.org/stonewall_jackson.htm

This is another valley must-see, especially for fans of Stonewall Jackson. Lieutenant Colonel Lewis T. Moore of the 4th Virginia Infantry owned this house, which he loaned to General Jackson for use as a headquarters during the winter of 1861–1862. Maintained today by the Winchester-Frederick County Historical Society, the museum presents Jackson’s office almost exactly as he left it. Many of Jackson’s personal belongings—including his personal prayer table and prayer book—are on display.

Museum is open Apr through Oct. Visitors can buy a block ticket good for admission to the Jackson Museum along with the Abram’s Delight Museum and George Washington’s Office Museum.

Harpers Ferry Ghost Tours

175 High St.

Harpers Ferry

(732) 801-0381

With so much history afoot in Harpers Ferry, you can expect to hear a good ghost story or two. This guided walking tour is offered nightly from Apr to Oct and by reservation Mon to Sat from Nov to Mar. Tours begin at the O’ Be Joyfull Center in Harpers Ferry.

Winchester Walking Tours

1360 S. Pleasant Valley Rd.

Winchester, VA

(540) 542-1326

Stop by the Winchester Visitor Center to pick up a copy of a guide to Winchester’s Civil War history, outlined in an easy-to-follow self-guided walking tour.

| The Angler’s Inn | $$–$$$$ |

867 W. Washington St.

Harpers Ferry

(304) 535-1239

There’s no doubt that The Angler’s Inn was designed with fishermen in mind, and with good reason. Harpers Ferry is located at the confluence of the Potomac and the Shenandoah Rivers, home to some of the best smallmouth bass and trout fishing in the country. But even if you’re sticking to dry land, the inn is an excellent choice for an overnight or weekend stay. Located less than a mile from the national park, this 1880 guesthouse is a favorite among travelers. There are four beautiful guest rooms, each with private sitting room and private bath. Its wraparound porch is perfect for reading and for savoring complimentary cookies and soda. Another draw: one of the best breakfasts you’ll ever taste, featuring entrees like omelets cooked to order, luscious waffles, and spiced bacon.

| Fuller House Inn and Carriage House | $$$$ |

220 W. Boscawen St.

Winchester, VA

(540) 722-3976

“Location is our specialty,” innkeeper Debra Johnson says of the Fuller House Inn, speaking of the downtown Winchester location of this charming inn, constructed in 1780. There are two rooms in the main house, outfitted with DVD players, refrigerators, and private baths, and guests enjoy complimentary wine and cheese and a delectable room service breakfast every morning. For extended stays, the Fuller House can also connect you with three additional properties: an 1854 Carriage House, a historic pre–Civil War house, or a downtown apartment.

| The George Washington Hotel, A Wyndham Historic Hotel | $$$–$$$$ |

103 E. Piccadilly St.

Winchester, VA

(540) 678-4700

www.wyndham.com/hotels/DCAGW/main.wnt

Wyndham Hotels took over the management of this vintage 1924 grand hotel and completed an extensive renovation in 2008. The result: a stunning 90-room historic hotel loaded with modern conveniences and genteel service befitting its elegant setting. On the premises, there’s a unique Roman-bath-inspired indoor swimming pool and a popular restaurant, The Dancing Goat, featuring an open kitchen and outdoor dining in season.

| The Herds Inn | $$$–$$$$ |

688 Shady Elm Rd.

Winchester, VA

(866) 783-2681

The Herds Inn stands out among the appealing B&Bs in this region, and with good reason. It’s a working dairy farm that serves up a one-of-a-kind rural experience. Guests check in to a hand-built log home and watch (and join in, if they wish) the day-to-day farm activities. There’s no shortage of activity; the farm is home to sheep, buffalo, goat, peacocks, chickens, turkeys, rabbits, dogs, and, of course, cows—and they’re eager to interact with guests. The inn accepts only one party at a time and offers a perfect setup for families.

| The Inn at Vaucluse Spring | $$$$ |

231 Vaucluse Spring Lane

Stephens City, VA

(540) 869-0200

(800) 869-0525

The Inn at Vaucluse Spring is not your typical B&B. It’s a fifteen-room B&B complex, spread across a hundred rolling acres near a limestone spring. Six guesthouses make up the property, voted one of the region’s most romantic inns by Washingtonian magazine, and there’s really something for everyone. Discerning travelers can luxuriate in an elegant manor house, while outdoors enthusiasts will feel right at home in a cozy log house dating to the 1850s. The rooms and houses come equipped with fireplaces, Jacuzzi tubs, porches, rocking chairs, and common areas perfect for savoring a glass of wine or curling up with a good book.

| The Jackson Rose Bed & Breakfast | $$$–$$$$ |

1167 W. Washington St.

Harpers Ferry

(304) 535-1528

Before Thomas J. Jackson earned the nickname “Stonewall,” he used this 1795 Federal-style mansion as a headquarters in spring 1861. He wrote to his wife, admiring the beautiful roses that grew in the garden outside his house. Jackson’s second-story room is one of four rooms available to guests at this B&B, and for Civil War buffs, it’s one of the most sought-after rooms in Harpers Ferry. Regardless of which room you check in to, you’ll enjoy beautiful antique furnishings, private baths, and a to-die-for breakfast featuring entrees like vegetable frittatas, French toast, fresh-baked muffins, and scones.

| Killahevlin Bed and Breakfast | $$$$ |

1401 N. Royal Ave.

Front Royal, VA

(540) 636-7335

(800) 847-6132

Killahevlin Bed and Breakfast is located on “Richardson’s Hill” in Front Royal. The house was built in 1905 by William Carson, an Irish immigrant who was largely responsible for getting Skyline Drive built. The house is on the National Register of Historic Buildings and the Virginia Landmarks Register. Two of Mosby’s Rangers were hanged on the property, and although the tree from which they were hanged was cut down and its wood sold to raise money for the Confederacy, the last remaining seedling from that tree remains on the grounds. Two Civil War crucibles were recovered by Mr. Carson from the site of a forge in Riverton, and are here on the property serving duty as flower pots. Owners and innkeepers Tom and Kathy Conkey offer warm Irish hospitality in their beautiful inn. Guests relax in sumptuous whirlpool tubs and queen-size beds while taking in breathtaking views of the mountains. Downstairs, there’s a private Irish pub, open 24 hours a day to guests, stocked with a delightful assortment of wine and beer—all you care to drink!

| Long Hill Bed and Breakfast | $$–$$$$ |

547 Apple Pie Ridge Rd.

Winchester, VA

(540) 450-0341

(866) 450-0341

Make a reservation at an inn located on “Apple Pie Ridge Road” and just try not to crack a smile. Innkeepers George and Rhoda Kriz claim that the ridge was named by Civil War soldiers who knew they could count on the Quakers who had settled in the area for food and shelter. The hospitality tradition lives on today in this three-room B&B. Rooms are charming and comfortable, equipped with whirlpool tubs, spacious closets, and other amenities. In cooperation with local historian Mac Rutherford, Mr. and Mrs. Kriz offer Civil War Driving and Civil War Walking Tour packages (in addition to a Ghost Tour package).

| The Lost Dog Bed and Breakfast | $$–$$$$ |

211 S. Church St.

Berryville, VA

(540) 955-1181

“We don’t have any local big box stores and only a few neon signs,” innkeeper Sandy Sowada says of Berryville, “so our charming main street with its barbershops, flower shop, bank, drugstore (with a soda fountain), retail stores, used book store, and restaurants all have that 1950s atmosphere.”

As for her inn, Ms. Sowada says: “My bed and breakfast (circa 1884) has three distinctive guest rooms, all with private bathrooms. We serve a full country breakfast featuring local eggs, produce, and meats, but we will cook for special diets with advance notice. We are located in the heart of the historic district, and our gardens offer something in bloom throughout the growing season. And of course, opportunities for outdoor exercise and visiting Civil War battlefields abound.”

| The Anvil Restaurant | $$ |

1290 W. Washington St.

Harpers Ferry

(304) 535-2582

Longtime visitors to Harpers Ferry and residents of the area can tell you all about the Anvil. It’s a local institution, known for its fresh seafood (including West Virginia’s celebrated trout), plus pastas, pizzas, and satisfying salad. The atmosphere is comfortable and casual, perhaps even a bit rustic, with an inviting outdoor patio that’s perfect for relaxing after a busy day on the Civil War trail.

| Battletown Inn and Gray Ghost Tavern | $$$ |

102 W. Main St.

Berryville, VA

(540) 955-4100

This quaint Berryville inn and eatery takes home the prize for the “most Civil War–sounding restaurant name" in the Winchester region. The menu tries to balance the North and the South, serving traditional Virginia recipes as well as New American and continental cuisine. Stop in for an ice-cold beer or a refreshing iced tea while passing through town, or check into the inn for a unique overnight stay.

| Brewbaker’s Restaurant | $$–$$$ |

168 N. Loudoun St.

Winchester, VA

(540) 535-0111

Brewbaker’s is a great choice for casual fare like zesty wings, juicy burgers, and seafood classics like crab cakes and crab balls. The kitchen shows off its playful side in creations like the “Chicken Everything”: chicken simmered in olive oil, along with mushrooms, onions, broccoli, sun-dried tomatoes, and crushed red peppers, and tossed with rigatoni and parmesan cheese. Or, there are the delightful pork loins, marinated in Montreal steak seasoning and served with an apricot merlot sauce with steamed vegetables.

| Cork Street Tavern | $$ |

8 W. Cork St.

Winchester, VA

(540) 667-3777

This no-frills Old Town Winchester eatery is housed in an 1830s building that survived heavy shelling during the Civil War as the city was passed back and forth between Union and Confederate command. Locals and visitors gather here for barbecued ribs (considered the best in the Shenandoah Valley), along with tangy barbecued pork sandwiches and Reubens.

| One Block West | $$$ |

25 S. Indian Alley

Winchester, VA

(540) 662-1455

Upscale dining finds its home in Winchester in chef/owner Ed Matthews’s stylish eatery, which takes its name from its location, one block west of the town’s historic strip. The casual, comfortable eatery shows off the freshest flavors of the Shenandoah Valley in an inventive menu that changes daily. Matthews browses local farmers’ markets for fresh ingredients like seafood, wild mushrooms, cheeses, and succulent cuts of bison, lamb, and duck. Look for delectable concoctions like caramelized sea scallops with local bok choy and grilled veal porterhouse with pancetta and sun-dried tomato cream.

| Secret Six Tavern | $$ |

186 High St.

Harpers Ferry

(304) 535-3044

After a long day of sightseeing, grab a table at Secret Six Tavern and soak up the breathtaking view of the town and the railroad that travels just below. True to the town’s historic traditions, the restaurant takes its name from the John Brown era. A group of Northern aristocrats who called themselves the “Secret Six” silently lent their support to Brown’s efforts to use force and arms to rid the nation of slavery. Included in this elite group of citizenry: the editor of the Atlantic Monthly, a Unitarian minister, a noted physician, an educator, and two philanthropists.

| Village Square Restaurant | $$$ |

103 N. Loudoun St.

Winchester, VA

(540) 667-8961

www.villagesquarerestaurant.com

At Village Square, chef Daniel Kalber shows his eye for fresh and local cuisine. On the menu, you’ll find interesting new interpretations of classic creations like diver scallops Oscar with lump crab meat and couscous pilaf, or tequila-lime marinated duck breast with wild rice chiles rellenos and roasted corn salsa. The restaurant forms part of downtown Winchester’s dining and entertainment strip.

| Violino | $$$ |

181 N. Loudoun St.

Winchester, VA

(540) 667-8006

Violino has staked out a position in the minds (and stomachs!) of Winchester-area residents and visitors for good Italian food, good Italian wine, and warm Italian hospitality. If you’re lucky, you might even catch chef and owner Franco Stocco emerging from the kitchen to belt a classic aria. While regulars love the family atmosphere, first-timers are usually here for the food—and they won’t be disappointed. Try the classic Italian fare or sample Stocco’s original creations like the Ravioli della Nonna Emilia, filled with Swiss chard and fresh goat ricotta cheese, served in a walnut sauce; a baked portobello topped with mushroom, parmesan, and rosemary puree; or a savory rib eye prepared in a Barolo wine reduction and served with roasted potatoes.