New Market/Staunton: The Central Valley

Discussions of the May 15, 1864, Battle of New Market often begin and end with colorful talk of the charge of the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) Corps of Cadets, which Confederate general John C. Breckinridge had called into service and sent into battle with great reluctance. It was an electrifying moment, at a crucial time of the battle. Even Union soldiers spoke with admiration of the young, gray-coated youths’ disciplined advance into galling Federal fire. Spectacle aside, the stout performance of the young cadets helped seal a Confederate victory of great strategic importance, one that bought time and resources for Robert E. Lee’s hard-pressed Army of Northern Virginia.

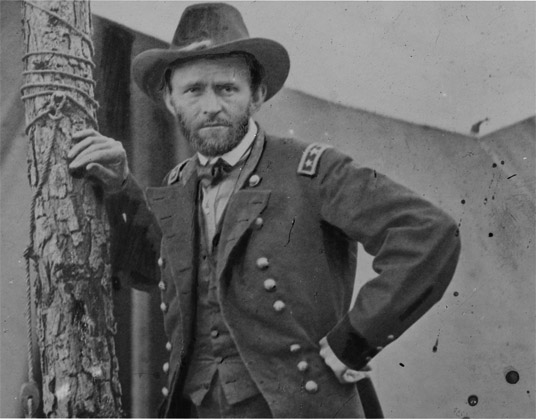

General Ulysses S. Grant

By the spring of 1864, Union armies had been trying unsuccessfully for more than two years to wrest control of the Shenandoah Valley from the Confederacy. Now President Abraham Lincoln had given command of Union armies to Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, who came east armed with a plan to end the war. His strategy called for a general advance by all Union armies. In the East, Grant would carry the brunt of the offensive against Lee in central Virginia, while Benjamin Butler marched up the James River and Franz Sigel—hopefully—took control of the troublesome valley. Sigel, whose military résumé was dotted with failures, was a courageous fighter but a poor general. His embarrassing flight from Wilson’s Creek in 1861 had cost many Union lives and sealed a Confederate victory in the war’s first major battle in the west. But politicking and his popularity with the Union’s thousands of German soldiers had kept him in uniform for three years, and now Grant had reluctantly assigned him a job no other Yankee general had been able to do.

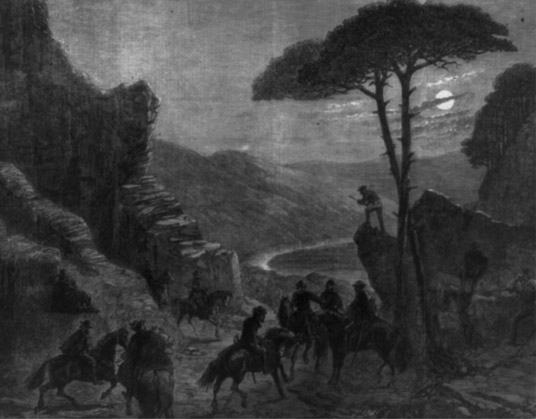

Dogged by John Mosby’s Confederate raiders, Sigel showed little urgency as he moved his 6,500 men south up the valley, prompting in his non-German-speaking troops “the most supreme contempt for General Sigel and his crowd of foreign adventurers.” Marching north to meet him was a patched-together force under Major General John C. Breckinridge, a 43-year-old Kentuckian with a square jaw and sweeping mustache. Breckinridge lacked the formal military credentials of his Federal counterpart; he had had just a smattering of military experience during the Mexican War. But he was a capable, intelligent leader; by 1861 he had already been elected James Buchanan’s vice president and served in the U.S. Senate. He was no Sigel. One aide (who happened to be the son of U.S. senator Henry Clay) called the general “the truest, greatest man I was ever thrown in contact with.”

It was Breckinridge’s job to protect Southern communications and transportation in the valley, while guarding the left flank of Robert E. Lee’s army, now locked in mortal combat to the east with Grant’s persistent Federals. That meant keeping Sigel—and any other Union force—from crossing the valley into the Blue Ridge gaps to north-central Virginia. The best way to do that, Breckinridge wisely reasoned, was to attack.

Early on May 15, Breckinridge reached the outskirts of New Market with a force of perhaps 5,000 men, including cavalry and 222 VMI cadets. After exchanging artillery fire with a few Union guns, Breckinridge pushed his two infantry brigades toward a thin Yankee line running west from the Valley Pike, north of town. The Federals were already falling back to a second position around noon when Sigel—who had been sending units up the pike piecemeal throughout the morning—finally reached the battlefield from Woodstock, 20 miles to the north. Even now his small army was incomplete.

Mosby’s raiders in a Blue Ridge Mountain pass above the Shenandoah

By 2 p.m., Breckinridge had secured New Market and was on the move, northward down the pike toward the first of two battle lines laid out by Sigel. Helped by accurate artillery fire, the Confederates sent Sigel’s skirmishers and then his entire first line scampering north; only some of the Bluecoats rallied at the new Yankee position. Brigadier General Gabriel Wharton’s Virginians seemed about to sweep through Sigel’s right when they ran into a fence planted across a rise called Bushong’s Hill. The Confederates stalled, as Yankee lead poured into their ranks. As the 62nd Virginia pulled back and re-formed, a gap opened between the regiment’s left and the dangling right flank of the 51st Virginia to the west. To avert disaster, Breckinridge now ordered up the anxious cadets, who had to this point been held in reserve.

In remarkable order, the boys marched forward into withering Yankee fire—slowed for just a moment—then, with cheers ringing around them, moved into the vacant slot alongside the shattered 62nd. Shortly after this, Sigel’s cavalry commander, Major General Julius Stahel, led 2,000 Yankee horsemen charging down the pike in driving rain toward the Confederate right—and into hell. What canister blasted from each side of the pike did not hit, Virginia infantrymen did. The Federal charge quickly disintegrated, and confused Yankee horsemen raced for the rear.

With the momentum of the battle suddenly changing again, a flustered Sigel decided to charge Breckinridge’s left. By now, however, the VMI boys had stabilized the Rebel line east of the pike; Breckinridge, in fact, even had another regiment, the 26th Virginia, coming up from reserve. Having disposed of Stahel’s cavalry, even Brigadier General John Echols’s two regiments had moved up on the right. In poor order, Sigel’s three regiments came forward—then one by one reversed course in the face of heavy artillery and rifle fire.

With Breckinridge’s lines advancing and Yankee infantrymen and artillerists withdrawing in haste, the day’s result became obvious. Only the awful weather and a brave rearguard defense offered by Captain Henry DuPont’s single Federal battery saved Sigel’s Bluecoats from slaughter. Meanwhile, Brigadier General Jeremiah Sullivan arrived north of New Market with two Ohio regiments too late for the battle, but in time to cover yet another shameless retreat by Sigel, who withdrew eight miles to Mount Jackson.

Sigel had matched his Kentucky counterpart in bravery, but in little else. Grant, shocked by word of Sigel’s loss and retreat, now could not get rid of the German fast enough. “By all means,” he wrote to Henry Halleck, “I would say appoint General [David] Hunter, or anyone else, to the command of West Virginia.” The hapless Sigel was briefly reassigned to Harpers Ferry and then relieved for good on July 8.

Sigel later blamed his failure in the valley on Lee, who, he claimed, had “the advantage of a central position” that left him “always ready and able to turn the scales in his favor.” But Lee—as Sigel well knew—was then locked in a death struggle with Grant and in no position to send bodies of troops anywhere. Sigel, who suggested the campaign could’ve been carried out in May 1864 with 20,000 troops, needed twice that by August.

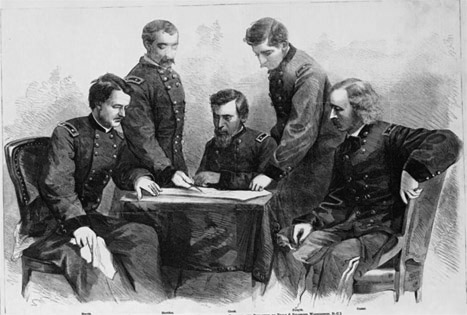

For three years, Confederate generals had run circles around the likes of Nathaniel Banks, John C. Frémont, and Franz Sigel in the Shenandoah Valley. During the past few weeks, Jubal Early had even knifed through the valley to threaten Washington. Now, on August 7, 1864, 35-year-old Major General Philip Sheridan took command of the 40,000-man Army of the Shenandoah with orders to secure the valley once and for all.

A fighting general with a strong dislike of his enemies, Sheridan quickly struck at Early’s much smaller force. Sheridan’s veterans whipped Early’s men at Third Winchester on September 19 and again two days later at Fisher’s Hill.

Convinced by early October that Early was beaten, Sheridan began to move north again—all the while burning anything that might aid his enemy. And after Union cavalry under George Armstrong Custer and Wesley Merritt smashed their Confederate counterparts at Tom’s Brook on October 9, Sheridan believed he had accomplished his mission.

General Philip Sheridan (center) and his generals

John C. Breckinridge

Vice President John C. Breckinridge

Only the Civil War, it seems, could have halted the political rise of John C. Breckinridge, the Kentuckian who climbed from the state legislature to the vice presidency by the age of 35. The unsuccessful presidential candidate of Southern Democrats in 1860, Breckinridge was still serving in the U.S. Senate a year later when his Southern sympathies aroused suspicion. Rather than wait for his impending arrest, Breckinridge fled south and, as he put it, exchanged “a term of six years in the U.S. Senate for the musket of a soldier.”

In a Confederate uniform, Breckinridge quickly proved that some politicians, at least, could make good generals. A born leader, he quickly gained the respect of his men and peers, developing his skills on the battlefields of Shiloh and Chickamauga before taking over the Confederate Western Department of Virginia in 1864. Following his reputation-making victory at New Market, Breckinridge reinforced Lee in the Wilderness, and then served under Jubal Early during his raid on Washington and subsequent defeat at Winchester. As the war wound down, Breckinridge moved to Richmond to become Jefferson Davis’s secretary of war—far too late to be of much use. This once-rising star in American politics then spent four years in exile before returning home to Kentucky, where he died in 1875.

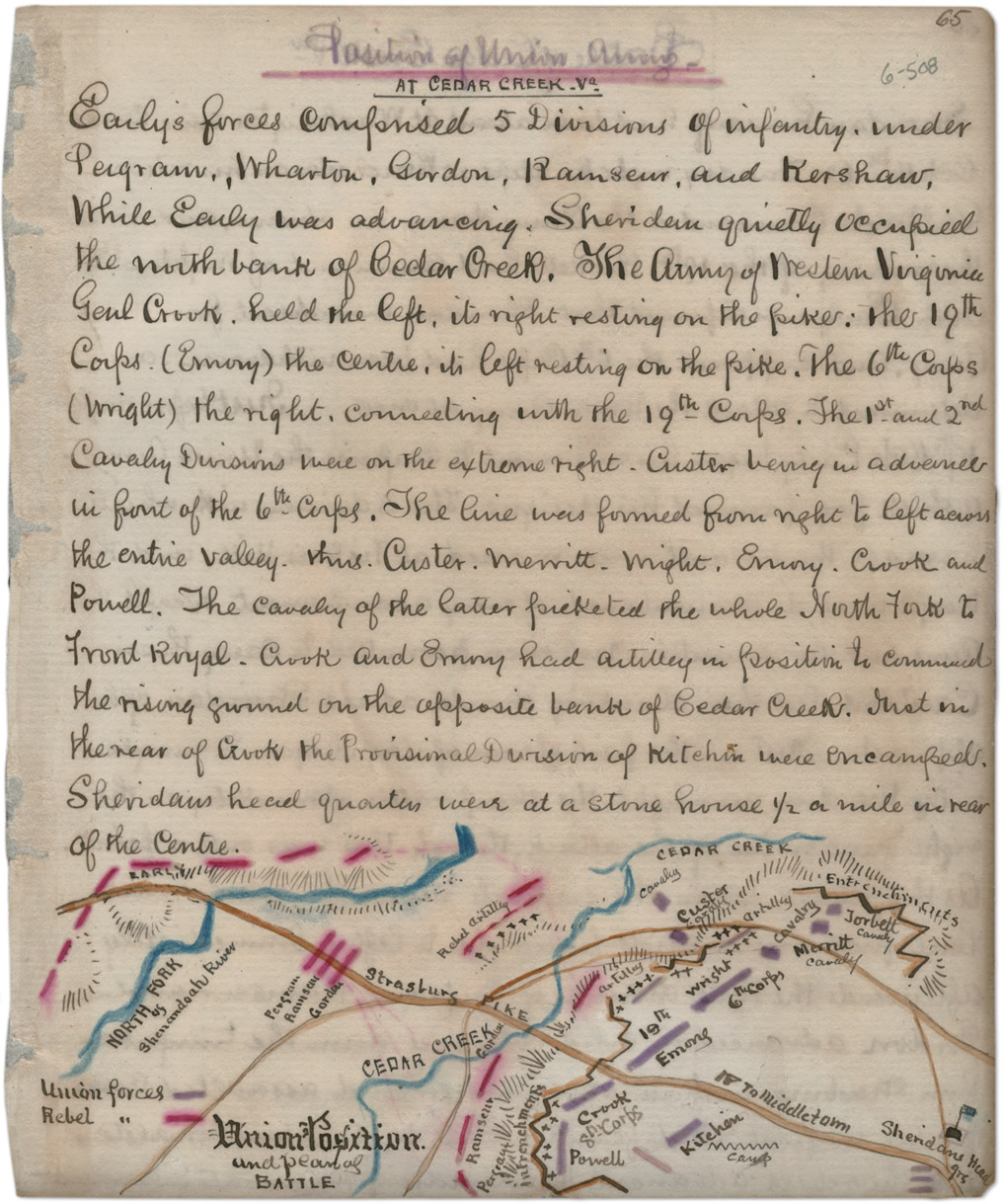

Map of the Battle of Cedar Creek

Sheridan, in fact, was absent from the army on the morning of October 19 when Early launched a surprise attack on the encamped Federals along Cedar Creek, southwest of Winchester. By mid-morning, Early’s divisions had scattered much of three Union corps, and the Confederate commander was sure of victory. But Union cavalry slowed the Confederates, and Brigadier General Horatio Wright (commanding in Sheridan’s absence) managed to establish a rallying point in a wood north of Middletown. Meanwhile, Sheridan—galloping at full speed from Winchester—reached the new Union line, received an update from Wright, and began preparations for a counterattack. First, though, the diminutive general rode slowly by the tightening Union ranks, reassuring each unit of success and rekindling the fighting spirit within each veteran. The awful morning was forgotten. Major Aldace F. Walker wrote later: “Cheers seemed to come from throats of brass, and caps were thrown to the tops of the scattering oaks; but beneath and yet superior to these noisy demonstrations, there was in every heart a revulsion of feeling, and a pressure of emotion, beyond description. No more doubt or chance for doubt existed; we were safe, perfectly and unconditionally safe, and every man knew it.”

What at first looked like a morale-boosting victory for the South was about to end instead with Jubal Early’s Confederates beaten and driven out of the Shenandoah Valley for good. Aside from some brief, afternoon skirmishing, the Cedar Creek battlefield remained quiet until 4 p.m., when Sheridan’s reinvigorated army trod vigorously out of the woods west of the pike. Sheridan’s right crashed into Early’s left—then, along with the rest of the advancing Federal line, ground to a halt before Confederate ranks blasting away from behind stone walls. Thirty minutes into the fight, however, George Custer’s division of blue-clad troopers—followed by William Dwight’s infantry—slammed into Early’s left and rolled up the Confederate lines. “Regiment after regiment; brigade after brigade,” John Gordon later recalled, “in rapid succession was crushed, and, like hard clods of clay under a pelting rain, the superb commands crumbled to pieces.” Just like that, the daylong affair turned. Where Union soldiers and wagon trains had clogged the pike heading north that morning, now the Confederates did the same, streaming south. With Early’s army went Southern hopes of further use of the valley, which had supplied Lee’s legions for four long years.

Cedar Creek Battlefield

8437 Valley Pike

Middletown, VA

(540) 869-2064

(888) 628-1864

Now part of the new Cedar Creek and Belle Grove National Historical Park, the Cedar Creek Battlefield remains under the care of the nonprofit Cedar Creek Battlefield Foundation. Founded in 1989 to stave off development on a key section of the original battlefield, the group sponsors annual reenactments to help fund ongoing preservation efforts. In recent years the group has been able to add a modern visitor center, bookshop, and exhibits to the building that houses the foundation’s offices. Efforts are now focused on restoring the Solomon Heater House, around which Confederate and Union forces once swirled.

Located at the intersection of Routes 81 and 66 (Route 11—the old Valley Pike—runs through the park), the visitor center is open between Apr 1 and Oct 31 and by appointment during the winter.

New Market Battlefield State Historical Park and Hall of Valor Museum

8895 Collins Dr.

New Market, VA

(866) 515-1864

This 300-acre park includes the hilly ground over which Union and Confederate forces clashed on May 15, 1864; the Jacob Bushong Farm; and the Hall of Valor Civil War Museum. Travelers should begin their visit with a trip through the Hall of Valor Museum, the exhibits of which explore the war in Virginia and the Battle of New Market—especially the role of the Virginia Military Institute cadets in that fight. While exploring the battlefield, visitors will want to look over the farm, which includes two Bushong family homes; a blacksmith shop; a henhouse; a loom and meat storage house; and a bake oven among its buildings, and remains a well-preserved reminder of 19th-century life.

Stonewall Jackson Museum at Hupp’s Hill

33229 Old Valley Pike

Strasburg, VA

(540) 465-5884

www.stonewalljacksonmuseum.org

This is a stop better suited for Civil War buffs with like-minded kids. Adjacent to the Cedar Creek Battlefield, the Hupp’s Hill grounds offer a walking tour of Confederate entrenchments and Union gun positions, while the site’s central building uses exhibits and photographs to tell the story of Stonewall Jackson and the war in the Shenandoah Valley. But the Hupp’s Hill staff focuses much of its efforts on children, offering camps each summer and encouraging kids to try on uniforms, handle reproduction weapons, and learn from Civil War games and living history workshops.

The museum also has a gift shop.

Cross Keys/Port Republic

Stonewall Jackson closed out his 1862 Valley Campaign with a pair of victories in lesser-known battles, at Cross Keys on June 8 and Port Republic on June 9. Currently, there are no visitor facilities at the sites, much of which remain private property. But there are interpretive highway markers and battlefield signs in the vicinity.

Fisher’s Hill Battlefield

Toms River, VA

There are no visitor facilities on the site of the September 22, 1864, Battle of Fisher’s Hill, in which Union major general Philip Sheridan bested General Jubal Early’s Confederates for the second time in three days. You can, however, follow a self-guided walking tour with trail markers on-site.

Gordonsville, VA

Gordonville’s Exchange Hotel was used as a hospital during the Civil War and now houses a small museum. You won’t find the massive exhibits of larger historic sites here, but it is worth a visit if you are in the area. Gordonsville visitors will also want to drop by the Gordonsville Presbyterian Church to see the pew in which Stonewall Jackson often prayed, and tour Maplewood Cemetery, where some 700 Southern soldiers were buried.

Shenandoah Valley/Skyline Drive

The valley’s natural beauty, inviting hiking trails, and other outdoor recreation opportunities are the reasons that most visitors visit the Shenandoah Valley. Travel on the Blue Ridge Parkway, also known as “Skyline Drive,” and you’re on the doorstep of more than one hundred Civil War sites. From the drive’s northernmost entry point in Front Royal, you can drive past points of interest like Luray Gap, where Stonewall Jackson announced that his command had become the Second Corps of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, and Lacey Springs, the site of a cavalry clash between Union general Custer and Confederate general Thomas L. Rosser. As you drive through the park, be sure to stop at a few of the scenic overlooks. Not only will you be rewarded with a breathtaking view of the rolling hillside, but you’ll also understand the strategic importance of the towns and mountain passes during the Valley Campaigns of 1862 and 1864.

| Apple Blossom Inn | $$–$$$$ |

9317 N. Congress St.

New Market, VA

(540) 740-3747

If you’re traveling through New Market and like the idea of having a historic house all to yourself, the Apple Blossom Inn is just the ticket. The two-bedroom, one-and-a-half-bathroom layout is perfect for a traveling family or two couples touring the battlefields together. Built in 1806, the house comes equipped with a parlor, a full kitchen, a music room, a cozy porch with a swing, and a peaceful garden. You’ll also enjoy a full cooked breakfast in the morning. The inn is the departure point for themed walking tours that bring New Market’s Civil War history to life.

The Apple Blossom Inn also organizes one-and-a-half-hour walking tours of the town. Call (540) 325-9529 or log on to www.appleblossominn.net/new-market-walking-tours.html for more information.

| Cross Roads Inn Bed and Breakfast | $$–$$$$ |

9222 John Sevier Rd.

New Market, VA

(540) 740-4157

(888) 740-4157

Larry and Sharon Smith’s Cross Roads Inn is pure Virginia in its country charm and hospitality. There are complimentary hors d’oeuvres at check-in, and you can help yourself to coffee and hot chocolate from the pantry of the 1925 house at any time of day. Rates are very reasonable, and rooms feature private baths, air-conditioning, antique furnishings, and other amenities; a number of specials are offered. Guests will enjoy the six-room inn’s common areas (including a fireplace in the living room), gardens, outdoor spa, and relaxing front porch. Reservations are recommended.

| The Inn at Narrow Passage | $$$–$$$$ |

US 11 South

Woodstock, VA

(540) 459-8000

(800) 459-8002

The Inn at Narrow Passage is one of Virginia’s longest-operating guesthouses, welcoming travelers since the 1740s. It takes its name from a dangerous nearby passage in the road, only wide enough for one wagon to cross at a time and constantly threatened by Indian attacks. During the 1862 Valley Campaign, Stonewall Jackson even checked in, using the inn as a headquarters. From here, he famously ordered Jedediah Hotchkiss to “make me a map of the valley.” Today’s guests can take advantage of historic guest rooms outfitted with wood floors, porches, and spectacular views of the Shenandoah River and Massanutten Mountain. A lavish breakfast is served fireside in the main dining room.

| Jacob Swartz House | $$$ |

574 Jiggady Rd.

New Market, VA

(540) 740-9208

(877) 740-9208

This private two-bedroom farmhouse, built in 1852 by cobbler Jacob Swartz, is loaded with Civil War history. When Virginia seceded from the Union in 1861, Swartz enlisted in the Confederate Army. His shoe-making services were deemed invaluable, however, and he was sent back home to make boots and equipment for the Southern forces. The Battle of New Market broke out just across the river from the family’s home. In December 1864, Federal troops under the command of George Custer raided the house and Swartz’s cobbler shop, taking food and supplies. Today the house is a pleasant country retreat, equipped with a wood-burning stove, fully stocked kitchen, and private screened-in porch overlooking the Shenandoah River.

| Piney Hill Bed & Breakfast | $$$$ |

1048 Piney Hill Rd.

Luray, VA

(540) 778-5261

(800) 644-5261

From the moment you arrive at Piney Hill, you’ll understand why it was named one of the top B&Bs in the country by TripAdvisor. Built in the early 1800s, the farmhouse offers a luxurious respite after a busy day of touring. Sip a glass of wine as you read a book on the wraparound porch, or take advantage of the outdoor Jacuzzi and the breathtaking views of the surrounding mountains. If you’re looking for more of an intimate experience, check into the Rosebud Cottage, also located on the property. It’s a cozy 500-square-foot house that’s perfect for a romantic getaway, outfitted with a screened-in porch and a gas fireplace; gourmet breakfast is delivered in a picnic basket to your doorstep every morning.

| Rosendale Inn | $$$–$$$$ |

17917 Farmhouse Lane

New Market, VA

(540) 740-4281

Presidential history buffs will find themselves right at home at the Rosendale Inn, located at the foot of Massanutten Mountain. Franklin Delano Roosevelt used the beautiful farmhouse as his retreat from the White House, and Mrs. Woodrow Wilson was also a guest at the B&B. Spacious rooms come furnished with period antiques and private bathrooms. Most have their own in-room fireplaces. Guests can also park themselves in rocking chairs on the veranda to soak up the picturesque scenery.

| South Court Inn Bed & Breakfast | $$$–$$$$ |

160 S. Court St.

Luray, VA

(540) 843-0980

(888) 749-8055

A magnificently restored 1870s farmhouse, the South Court Inn is a popular choice among travelers who are exploring the beautiful Shenandoah Valley, its wineries, and quaint antiques shops. Perfect for a romantic escape, most of the inn’s rooms feature whirlpool tubs, and innkeepers Tom and Anita Potts are happy to help you arrange in-room massages, roses, champagne, and other extras. You’ll wake up to a delicious and decadent breakfast of banana-stuffed French toast, soufflés, and other treats that you wouldn’t normally make for yourself. For a little more privacy, you can rent the Susie Hodges Cottage.

| The Staunton Choral Gardens Bed and Breakfast | $$–$$$$ |

216 W. Frederick St.

Staunton, VA

(540)885-6556

www.stauntonbedandbreakfast.com

A bit south of this tour’s more notable attractions, the Staunton Choral Gardens is right on the way to Lexington and within easy reach of Appomattox and other central Virginia Civil War sites. And like almost every other property in the valley, it has its own Civil War story connected to it. According to owner Carolyn Avalos, Robert E. Lee—whose daughters attended a private school across the street—regularly boarded his horse Traveler in the inn’s carriage house when he took a train from Staunton.

Naturally noted for its beautiful gardens, Staunton Choral Gardens offers warm, comfortable rooms, free high-speed, wireless Internet service, and other modern amenities. Adjacent to the inn’s main building is the historic carriage house, now “a luxurious, two-story suite,” Carolyn Avalos says, “very inviting and quite unique—all redone but keeping the charm.” The inn is located within walking distance of all the town’s attractions, which can also be reached via free trolley service.

| Stonewall Jackson Inn | $$$–$$$$ |

547 E. Market St.

Harrisonburg, VA

(800) 445-5330

Civil War buffs will no doubt be attracted to an inn named after one of the war’s most legendary figures. At this Harrisonburg bed-and-breakfast, each of the ten guest rooms is named for another prominent Civil War figure, from Grant to Sheridan to Pickett. The rooms are decorated with period antiques and replicas, as well as works by local artists. You’ll also enjoy a private bath, wireless Internet, and cable TV in each guest room, and a scrumptious breakfast featuring Virginia ham, Virginia apples, and locally produced sausage. The circa-1885 mansion itself is architecturally unique, a combination of a Queen Anne mansion and a New England–style cottage.

| A Moment to Remember | $$ |

55 E. Main St.

Luray, VA

(540) 743-1121

If you’re staying in Luray or paying a visit to its attractions, stop for breakfast, lunch, or dinner at A Moment to Remember. Start your day with an omelet made with fresh Virginia ham or a stack of buttermilk pancakes, feast on salads or sandwiches for lunch, and enjoy a selection of seafood entrees for dinner. Or, stop by between meals for an invigorating espresso drink or a light bite.

| Jalisco Authentic Mexican Restaurant | $$ |

9403 Congress St.

New Market, VA

(540) 740-9404

You might be surprised to find authentic Mexican fare in a little town like New Market, but you won’t be disappointed by the zesty flavors, generous portions, and friendly service. The extensive menu is chock-full of combination platters, grilled specialties, and vegetarian selections, which taste even better when paired with a traditional margarita (or one flavored with strawberry or peach).

| Mill Street Grill | $$ |

1 Mill St.

Staunton, VA

(540) 886-0656

If you travel as far south as Staunton, stop for a bite at the Mill Street Grill. Don’t be surprised to see a waiting line at this casual pub-style eatery; it’s no secret that Mill Street serves the best fall-off-the-bone ribs for miles around. Choose from baby back pork ribs, beef ribs, prime rib, or a combination of the above, expertly seasoned and served with fresh coleslaw, your choice of potato, and fresh bread accompanied by the flavored butter of the day. If you’re not in the mood for ribs, you can feast on other grilled and fried creations, including chicken, seafood, steak, and more. Portions are generous, but there’s also a “light side” menu with several tempting lower-calorie selections.

| Mrs. Rowe’s Restaurant and Bakery | $$ |

74 Rowe Rd.

Staunton, VA

(540) 886-1833

If you’re traveling to Staunton and are hungry for a home-cooked meal, stop by Mrs. Rowe’s for all-American classics. The menu is loaded with Southern favorites like sweet potato pie, fried chicken, meatloaf, collard greens, and other tasty dishes. If you’ve got a sweet tooth, you won’t want to miss the homemade pies, cakes, and sweets. If you’re eating on the run, order dinner to go.

| Southern Kitchen | $ |

9576 S. Congress St.

New Market, VA

(540) 740-3514

It would be hard to top Southern Kitchen for hearty American fare such as fried chicken and pie, all of which are served in generous helpings. Owned and operated by the Newland family since 1955, the diner-style eatery is a favorite of visitors to the valley. You’ll find regional specialties like peanut soup and honest-to-goodness Virginia ham, plus seafood selections like flounder, rainbow trout, and fried shrimp. It’s open daily from 7 a.m. to 9 p.m.