Washington, D.C.: The Capital

Civil War–era Washington, D.C., was a city of contrasts, one part bustling metropolis and one part muddy, frontier boomtown. In its drinking establishments, robust support for both the Union and the new Confederacy was voiced. Politicians and foreign visitors gathered in the ever-popular Willard Hotel to debate the merits of the states’ rights. Loud arguments occasionally degenerated into fights in the Senate and House; congressmen armed with pistols and derringers walked the streets prepared to defend their beliefs.

Would-be soldiers seeing the city for the first time had differing impressions. Poor sewage and drainage systems contributed to a rising stench from the Potomac River that summer heat only magnified. And it was hard to think of a city in which pigs roamed the streets as the national capital. (One evening that summer, an army lieutenant chasing a skulker down Pennsylvania Avenue captured his quarry when the man tripped over a cow napping in the street.) Even the Capitol was a mess. For nearly a decade, engineers, masons, and carpenters had been busy refurbishing the building; but even now, the iron dome designed to replace the original wooden model remained unfinished. And with war clouds forming, mobilization of a national army would only add to the city’s transitory appearance.

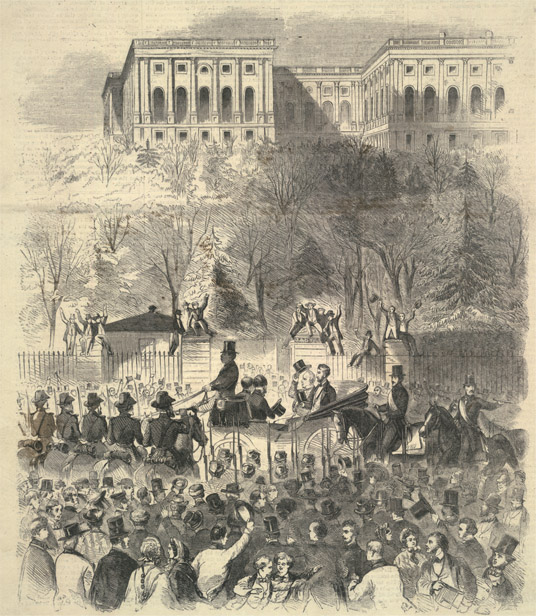

Lincoln’s inaugural procession passes the Capitol gate.

Here, on March 4, 1861, a broad mix of locals and out-of-towners packed the shoulders of Pennsylvania Avenue to catch a glimpse of the tall, lanky Westerner about to be inaugurated as president. At noon, Abraham Lincoln emerged from the Willard Hotel with his white-haired, careworn predecessor, James Buchanan, and they climbed into a carriage to make the short trip to the U.S. Capitol. It loomed up behind the gathered dignitaries as if to remind them of the important national work at hand.

From the Capitol’s east portico, Lincoln delivered his inaugural address to a crowd gathered below the watchful eyes of soldiers posted atop nearby buildings. In his closing remarks, the former lawyer reached out to the South, where seven states had already seceded from the Union:

We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies … The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

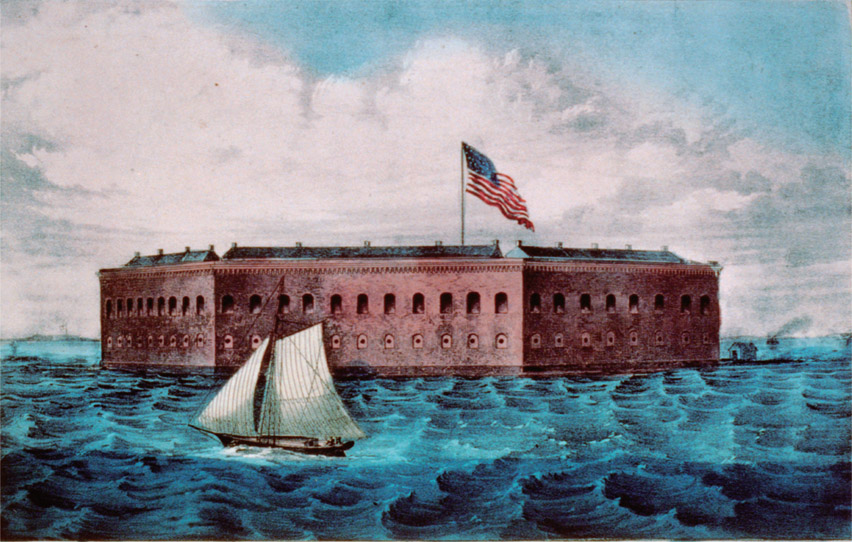

The April 12 Confederate bombardment of Fort Sumter, however, shattered any remaining illusions of peace. And after a Rebel Army sent thousands of Yankees fleeing back from Manassas into the capital in July, the threat of a Confederate attack on Washington took on real meaning. Union engineers went to work constructing an elaborate defensive ring around the city—one that by 1865 would include some 160 separate forts and batteries linked by rifle pits in a 37-mile arc. Only once was this ring challenged, and then not seriously. In July 1864, Jubal Early led a force of 14,000 Confederates down (north) the Shenandoah Valley, past a hastily gathered Union force at the Monocacy River, and to the northern outskirts of the city. But Early, who was really trying to divert Union troops from Petersburg, quickly retreated back onto home ground. Panicked city residents breathed a collective sigh of relief.

Fort Sumter

War changed the District. The mud and wandering farm animals remained, but Abraham Lincoln, the man who had done so much to bind the nation back together, was gone, assassinated by John Wilkes Booth within days of Robert E. Lee’s surrender. His replacement, Tennessean Andrew Johnson, would soon prove to be a shadow of his predecessor.

But with the war over, thousands of soldiers were returning home—packing up tents and vacating the vast earthworks that had turned the city into an armed, itinerant camp. Black codes were gone, the Thirteenth Amendment had been passed, and free African Americans were assuming a more visible place in Washington society. Peace and hope had returned. Even the capitol dome—long the symbol of a shattered nation—had been finished.

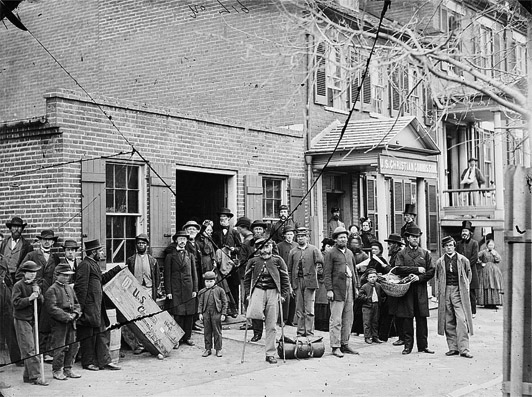

Civil War soldiers in Washington, D.C.

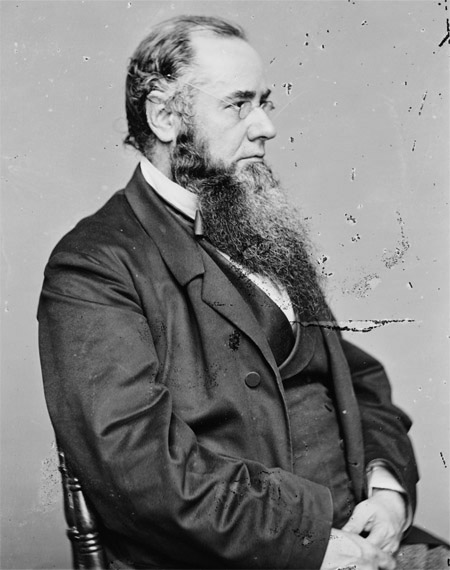

Edwin M. Stanton

“The dreadful disaster of last Sunday can scarcely be mentioned,” wrote Edwin M. Stanton following the Union defeat at Manassas on July 21, 1861. “The imbecility of this Administration culminated in that catastrophe—an irretrievable misfortune and national disgrace never to be forgotten…. the capture of Washington now seems inevitable.” The gruff Stanton, an ardent Democrat and, until a few months prior to the battle at Manassas, James Buchanan’s attorney general, was one of Abraham Lincoln’s harshest critics in the early days of the Civil War. Six months later he was Lincoln’s secretary of war, with the two eventually becoming warm friends and ironclad partners in the war to end the Rebellion.

A lawyer by trade, the bespectacled and bearded Stanton was not an easy man to like. He preferred to have his own way, suffered opposing opinions with little patience, and was unafraid to make his own feelings clear—as Lincoln was well aware. By January 1862, he was also a close friend of George B. McClellan, the reigning Army of the Potomac commander, who would prove to be more of a thorn in the side of Lincoln than Robert E. Lee. Stanton had earned notoriety in 1859 when he defended congressman Daniel Sickles (by 1861 a Union officer) in a murder case that rocked the capital. Entering a plea of “temporary insanity”—a defense never before used successfully in the United States—Stanton won an acquittal for a man who had shot his wife’s lover (U.S. Attorney Philip Barton Key, son of Francis Scott Key) in broad daylight in D.C.’s Lafayette Square.

Overriding his personal opinion of Lincoln or politics in general was Stanton’s love of the Union. He quickly justified the president’s faith in him by straightening out a War Department riddled with corruption and left a shambles by his predecessor, Simon Cameron, whom Lincoln had deftly made ambassador to Russia. A capable and efficient administrator, Stanton banished undedicated government employees, canceled wasteful government contracts, and moved the telegraph office into the War Department offices, where he and Lincoln spent endless hours poring over reports from the field.

Between these two former lawyers, a firm partnership formed—one based on a love of law, belief in the Union, appreciation of each other’s strengths, and within months, a disdain for George McClellan. Once a member of the Lincoln administration, Stanton quickly saw his old friend for what he really was—a conniving, vacillating organizer unwilling to or incapable of leading an army. Joining the voices already raised against McClellan, Stanton urged Lincoln to replace the Army of the Potomac commander. Having learned to manage his irascible secretary, the president did—but only when the time was right.

By April 1865, the partnership of Lincoln and Stanton had overseen the final Union victory. The secretary was one of those that visited the wounded president’s bedside as he lay dying on April 14 and 15. And when Lincoln passed, it was a heartfelt Stanton who uttered the immortal words: “Now he belongs to the ages.”

African American Civil War Memorial

U St. and Vermont Ave. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 667-2667

Dedicated in 1998, this memorial honors the more than 200,000 African-American soldiers who fought to preserve the Union. The centerpiece of the memorial is “Spirit of Freedom,” a 10-foot statue bearing the likenesses of young black soldiers and a sailor, created by Kentucky artist Ed Hamilton. It was the first major work by an African-American sculptor to earn a place of honor on federal land in Washington, D.C. Surrounding the statue is a granite-paved plaza encircled by walls bearing the names of the men who served. The memorial is located in the Shaw neighborhood, named for Robert Gould Shaw, the white colonel who led the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry’s troops, as immortalized in the movie Glory. Near the memorial, the African American Civil War Memorial Freedom Foundation Museum and Visitors Center (1200 U Street NW) offers further insight into the black experience during the Civil War. Admission is free.

Clara Barton National Historic Site

5801 Oxford Rd.

Glen Echo, MD

(301) 320-1410

The founder of the American Red Cross first made her mark caring for wounded soldiers of the Civil War, both on and off battlefields, earning for herself the moniker “Angel of the Battlefield.” A bullet nearly ended her career at Antietam. Clara Barton National Historic Site is open for guided tours daily. Admission is free.

Donald W. Reynolds Center for American Art and Portraiture

8th and F Sts. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 633-1000

This magnificent Greek Revival building was constructed between 1836 and 1868 to serve as the U.S. Patent Office, developed under the guidance of then-president Andrew Jackson. One of the District’s earliest “tourist traps,” visitors would flock to the building to view models of new gadgets and gizmos seeking patent protection. The glorious building also played host to Lincoln’s second inaugural ball. Today it’s an attraction once again, housing two of the Smithsonian Institution’s art collections, the National Portrait Gallery and the Smithsonian American Art Museum—both of which hold significant collections of Civil War–era art. In the National Portrait Gallery’s presidential portraits collection (the only complete collection, outside of the White House), there’s a photograph of Lincoln taken by Alexander Gardner on a glass negative in February 1865. The negative broke, producing a crack that crosses the crown of Lincoln’s head. The crack has since been interpreted as an omen for the impending assassination. Admission is free.

Ford’s Theatre National Historical Site

511 10th St. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 347-4833

There’s no American theater that’s quite as historic as Ford’s. On April 14, 1865, President and Mrs. Lincoln joined Major Henry Reed Rathbone and Clara Harris for a performance of Our American Cousin. While the president and his party were seated in the presidential box, they were surprised by Confederate activist and actor John Wilkes Booth, who shot Lincoln and stabbed Rathbone before leaping to the stage in an attempt to escape. Lincoln died at 7:22 the next morning at the Petersen House, located directly across the street. The theater closed its doors immediately after the assassination and served as a warehouse, museum, and office building for 90 years before President Eisenhower authorized its restoration in 1954. Ford’s reopened in 1968 and has since functioned as a working theater known for its productions of American stage classics.

If you’re not able to catch a play, it’s still worth the trip to see the theater itself, largely restored to the way it looked in 1865. The lower level houses a museum packed with artifacts, including Booth’s .44 caliber derringer and informative displays discussing the assassination conspirators and their trials. You can also walk across the street to tour Petersen House and see the room where Lincoln died. Ford’s Theatre is open daily (except during matinee performances). Admission is free.

Frederick Douglass National Historic Site

1411 W St. SE

Washington, D.C.

(202) 426-5961

The former slave who became one of the giants of the Civil War era purchased this 21-room home in 1877. Known as Cedar Hill, the historic home is located across the Anacostia River, offering a spectacular view of Washington, D.C.’s cityscape to the north. The museum offers exhibits, interpretive programs, and a film which tells the story of Douglass’s life. Reopened in February 2007 following an extensive renovation, the glorious home was restored to look as it did in Douglass’s day.

International Spy Museum

800 F St. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 393-7798

There’s no doubt that this high-touch, high-tech museum has a post-WWII focus, but Civil War spies like Belle Boyd and Rose Greenbow do factor into a few of its exhibitions. Time-travel forward into the 20th century to see Cold War gadgets like buttonhole cameras, lipstick guns, and cipher machines, or to take part in Operation Spy, the museum’s new hour-long, immersive espionage experience. Museum hours vary by season.

Library of Congress

Independence Ave. at 1st St. SE

Washington, D.C.

(202) 707-8000

While the Library of Congress is the world’s largest library, it’s more than just a collection of books. Housed in one of Washington, D.C.’s most spectacular spaces, the Library is a treasure trove of priceless national and international artifacts. Although the exhibited items change, the Civil War is always a theme in the Library’s American Treasures gallery, and researchers find it an invaluable resource for deeper investigations into pivotal events in American history. Admission is free.

Lincoln Memorial

The National Mall at 23rd St. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 426-6841

If you only have time to visit one memorial in Washington, D.C., make it this powerful tribute to the president who worked to keep the country together during the tumultuous war. It’s symbolically located across the Memorial Bridge from Arlington National Cemetery, where Robert E. Lee’s plantation home looms in the distance, representing the reunion of the two sides. In another symbolic gesture, the memorial’s 36 columns represent the 36 states that were reunited at the time of the assassination. Read a passage from the Gettysburg Address on one side of the marble temple and an excerpt from Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address on the other. Admission is free.

National Archives Building

700 Pennsylvania Ave. NW (entrance on Constitution Ave. between 7th and 9th Sts. NW)

Washington, D.C.

(202) 357-5000

While the National Archives is best known as the home of the original Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights, the National Archives is a must-see for anyone conducting Civil War research. It’s here that you’ll find draft records, court-martial case files, photographs, and key pieces of correspondence, including a recently uncovered letter from Lincoln to his general-in-chief Henry Halleck in 1863 suggesting that if General George Meade could follow up his victory at Gettysburg with another defeat of Robert E. Lee and his southern troops, the war would be brought to an end. Admission is free.

National Museum of American History

14th St. and Constitution Ave. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 633-1000

Also known as “America’s Attic,” this popular Smithsonian Institution museum houses artifacts of U.S. history, pop culture, politics, technology, and more. American military history, along with social history and presidential lore, are themes that show up in various parts of the vast collection. Admission is free.

National Museum of Health and Medicine

6900 Georgia Ave. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 782-2200

What’s now a repository for medical artifacts, anatomical and pathological specimens, and other health-related materials started in 1862 as the Army Medical Museum, designed to help improve medical procedures and conditions during the Civil War. The museum still operates as part of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, but its focus has expanded beyond battlefield medicine to include civilian artifacts and exhibitions on timely medical topics. True to its roots, there’s still a significant collection of Civil War relics, including the bullet that killed Abraham Lincoln and the probe used in his autopsy. You’ll also find a shattered leg bone from Major General Daniel Sickles, who famously murdered Francis Scott Key’s son, Philip Barton, in a crime of passion in 1859. Sickles was acquitted of the crime in the first successful application of the “temporary insanity” defense. When war broke out in the aftermath, he joined the army to clean up his tarnished reputation. He was struck by a cannonball at Gettysburg and donated his mangled leg to the Army Medical Museum. The major general reportedly visited the specimen every year on the anniversary of the amputation, and some say that his ghost continues to visit today. Admission is free.

Renwick Gallery of Art

17th St. and Pennsylvania Ave. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 633-7970

Now one of the Smithsonian Institution’s repositories of American art, the Renwick Gallery served as a supply depot for Union forces from 1861 through 1864 and as headquarters for General Montgomery C. Meigs, army quartermaster, in 1865. Magnificent paintings and crafts hang where uniforms, tents, and other essentials were once meted out to soldiers on their way to fight in Virginia.

U.S. Capitol

1st St. between Independence and Constitution Aves.

Washington, D.C.

(202) 226-8000

During the Civil War, the Capitol was more than just a meeting place for senators and congressmen. It was used by Union forces as a barracks for about 4,000 troops, a hospital, and even a bakery where bakers made about 16,000 loaves of bread each day. Today, it’s better known for its official function as a meeting, working, and debating place for members of Congress. All visitors must join a ticketed, guided tour to view the Capitol’s interior. Complimentary tickets are distributed at the Capitol Guide Service kiosk (near the intersection of First Street and Independence Avenue SW) beginning at 9 a.m. Mon through Sat. Admission is free.

Washington Monument

Constitution Ave. and 15th St. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 426-6841

When war broke out between the States, the 555⅛-foot tall Washington Monument was nearly a third complete, although construction had begun in 1848. Demand for building supplies, funds, and able-bodied troops brought construction of the delay-plagued monument to a halt. Construction resumed in 1876, and the monument was completed in 1888, but thanks to the long delays, the marble on the bottom third of the obelisk was taken from a different level in the quarry. As a result, it’s a different color. Free tickets are required to ride to the top of the monument; they are distributed beginning at 8:30 a.m. at the ticket kiosk on 15th Street. The monument is open from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily, with the last tour beginning at 4:45 p.m. Admission is free.

The White House

1600 Pennsylvania Ave. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 456-1414

At the time of the Civil War, the White House looked different than it does today. In fact, it wasn’t even officially called the White House. That name was formally bestowed on the presidential residence during the Theodore Roosevelt administration. The mansion was much smaller and quite crowded with the Lincolns and their young family. Conditions were also much less sanitary; sewage emptied onto the Ellipse, fueling diseases like smallpox and typhoid, which claimed the life of Lincoln’s son, Willie. The White House Visitors Center, located at 14th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, sheds some light on the building’s history and its role in the Civil War. Touring the building itself requires advance arrangements; contact your Congress member up to six months in advance to inquire about tours, which are available Tues through Sat for groups of 10 or more. Admission is free.

Admiral David G. Farragut Memorial

Farragut Square

17th and K Sts. NW

Washington, D.C.

Washingtonians know Farragut Square as one of the busiest office districts, home to two bustling Metro lines. The 10-foot statue that sits at the middle of the square honors Rear Admiral David G. Farragut, whose heroics led to the Union’s capture of New Orleans and Mobile Bay. Vinnie Ream Hoxie, the creator of the statue, was the first female sculptor to be commissioned by the U.S. government.

Blair House

1651-53 Pennsylvania Ave. NW

Washington, D.C.

Located directly across the street from the White House on the most protected block of Pennsylvania Avenue, Blair House is best known as the home-away-from-home for foreign heads of state and royalty on official state visits. It’s not open to the public, but Civil War buffs may want to stroll past this house for its historic significance. It’s here where Robert E. Lee turned down Lincoln advisor Francis P. Blair’s offer to command the Union troops, vowing his allegiance to his home state of Virginia instead.

Fort Dupont Park

Minnesota Ave. and Randle Circle SE

Washington, D.C.

(202) 426-7745

Fort Dupont was established in 1861 by Union forces as a means of protecting the 11th Street Bridge, an important link between the Southeast neighborhood of Anacostia and the capital city itself. No battle was fought here, but the fort gained some notoriety as a safe haven for runaway slaves. Little remains of the fort today, but you can still see its earthworks in the 376-acre Anacostia park that shares its name. The park’s Activity Center is open Mon through Fri; the park is open from sunup to sundown.

General George B. McClellan Monument

Connecticut Ave. and California St. NW

Washington, D.C.

Near Washington, D.C.’s Adams Morgan neighborhood, there’s a statue of McClellan, the Union commander who faltered during the Peninsula Campaign, then emerged victorious at Antietam. Despite his victory, tactical errors caused Lincoln to question his judgment and eventually relieve him of his command. McClellan also had a mixed showing in his political career; he ran unsuccessfully against Lincoln for the presidency in 1864 but served as governor of New Jersey from 1878 to 1881. In his memorial statue, designed by Frederick MacMonnies and dedicated in 1907, he sits atop a horse, overlooking Connecticut Avenue.

General John Alexander Logan Statue

Logan Circle, Vermont Ave. at 13th and P Sts. NW

Washington, D.C.

A traffic circle in one of the District’s trendiest residential areas is named for General John Alexander Logan. In the center of the circle there’s a bronze equestrian statue of Logan, dedicated in 1901. Logan fought with distinction in some of the war’s biggest battles—Manassas, Vicksburg, and Atlanta—before losing a bid for the vice presidency in 1884.

General Philip Sheridan Monument

Sheridan Circle

Massachusetts Ave. and 23rd St. NW

Washington, D.C.

Surrounded by some of Washington, D.C.’s finest embassies and diplomatic addresses, this equestrian statue was crafted by Gutzon Borglum, best known for his sculptures at Mount Rushmore. The Union commander led the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac in the East, pursuing Robert E. Lee and forcing his surrender at Appomattox.

General William Tecumseh Sherman Monument

Sherman Square

15th St. and Pennsylvania Ave. NW

Washington, D.C.

Sherman served valiantly under Grant at the Battle of Vicksburg and then took Grant’s place as Union commander in the western theater of the war. He led troops to capture Atlanta in September 1864, ensuring Lincoln’s reelection. Afterwards, his armies embarked on a devastating march through Georgia and the Carolinas. He’s commemorated in a mounted statue in a small park nestled between the White House Ellipse and the Department of the Treasury.

General Winfield Hancock Scott Memorial

Pennsylvania Ave. at 7th St.

Washington, D.C.

Dedicated in 1896, this statue honors General Scott, best known for his triumph over Robert E. Lee at Gettysburg. Considered one of the most capable commanders of all time, Scott is also credited with developing the Union’s Anaconda Plan, which brought down the Confederacy.

Major General George C. Meade Monument

Pennsylvania Ave. and 3rd St. NW

Washington, D.C.

George Meade is credited with orchestrating Lee’s defeat at Gettysburg. By positioning his troops for defensive attacks on the left, right, and center, he successfully fended off Pickett’s Charge. The marble monument, crafted by Charles A. Grafly, was dedicated in 1927.

Major General James B. McPherson Monument

McPherson Square, Vermont Ave. between 15th and K Sts. NW

Washington, D.C.

Constructed from a seized cannon by Louis Rebisso, this equestrian statue honors McPherson, Ulysses S. Grant’s chief engineer, who commanded the army of Tennessee and faltered near Atlanta. It was dedicated in 1876.

The Peace Monument

Pennsylvania Ave. at 1st St. NW

Washington, D.C.

Built to honor U.S. Navy casualties in the Civil War, this 44-foot marble statue and fountain sits in front of the U.S. Capitol. It was sculpted by Franklin Simmons in 1877. Facing west, toward the National Mall, a female figure representing Grief hides her face on the shoulder of another female figure, representing History. In her hands, History clutches a stylus and tablet reading “They died that their country might live.” Below Grief and History, another female figure, Victory, holds a laurel wreath and oak branch, symbolizing strength. Mars and Neptune, representing War and the Sea, sit just below. A final female figure, Peace, looks out toward the Capitol.

The Rock Creek Park Forts

Rock Creek Park

3545 Williamsburg Lane NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 895-6000

Washington, D.C.’s vast urban playground is home to the remains of forts that once protected the capital city. At Fort Stevens (13th and Quackenbos Streets, NW), Jubal A. Early’s Southern forces took on the Union defenders in 1864 as federal notables, including Abraham Lincoln, looked on. Just north of the fort, Battlefield National Cemetery is the final resting place of the 41 Union soldiers who died defending the fort. There’s nothing left at Fort Reno (Belt Road and Chesapeake Street NW), but, as the highest point in the city, the grounds do open up to an incredible view. Also nearby: Ford DeRussey (Oregon Avenue and Military Road NW) and Fort Bayard (Western Avenue and River Road). You can find some parts of the forts still standing at Fort Slocum Park (Kansas Avenue, Blair Road, and Milmarson Place NE), Fort Totten (Fort Totten Drive, south of Riggs Road), and Battery Kemble Park (Chain Bridge Road, MacArthur Boulevard, 49th Street, and Nebraska Avenue).

Ulysses S. Grant Memorial

Union Square, 1st St. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 426-6841

Set against the backdrop of the U.S. Capitol, this striking tribute to Grant was sculpted by Henry Shrady and dedicated in 1922. The statue itself—the largest equestrian statue in the country and the second largest in the world—was modeled after a sketch that Grant drew of a soldier from Massachusetts after the battle at Spotsylvania Court House, surveying the National Mall to the west.

Washington Arsenal Site

4th and P Sts. NW

Washington, D.C.

Now home to Fort McNair, the Arsenal was used to ship supplies to battle sites in Virginia. John Wilkes Booth and his co-conspirators were brought here after Lincoln’s assassination, where they were later tried and hanged.

Cultural Tourism DC (www.culturaltourismdc.org) acts as an umbrella group for many of Washington, D.C.’s small museums and neighborhood heritage sites, many of which are listed in this guide. Walking tours and bus tours of Washington, D.C.’s Civil War heritage sites are occasionally available; you can also download a copy of Cultural Tourism DC’s “Civil War to Civil Rights” walking tour route in downtown D.C.

Gray Line (www.grayline.com) offers regular day-long tours of Gettysburg departing from downtown Washington, D.C.

| Adams Inn | $$–$$$$ |

1744 Lanier Place NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 745-3600

(800) 578-6807

This cheery, comfortable inn is popular with family travelers, backpackers, and even business travelers—and with good reason. The rooms are clean, neatly furnished, and very affordable. Fifteen of the inn’s 25 guest rooms come with private bath, and all guests enjoy continental breakfast, high-speed Internet, and laundry privileges. The surrounding Adams Morgan neighborhood serves up some of the city’s best international cuisine, along with fun and festive nightlife.

| Chester A. Arthur House Bed and Breakfast at Logan Circle | $$$$ |

13th and P St.

Washington, D.C.

(202) 328-3510

(877) 893-3233

Civil War buffs will feel right at home at the Chester Arthur House, which is located on a circle named for Major General John Logan. An equine statue of the man credited as the inspiration behind Memorial Day overlooks the area. One may care little for Logan (who was probably the best of Lincoln’s political generals) or Chester A. Arthur (the inn’s namesake and the nation’s 21st president), but the gracious comfort and beautiful decor of this 1883 townhouse will win anyone over. The inn’s location and guest-room rates are excellent. But there are just three rooms, so call well in advance.

| The Dupont Hotel | $$$$ |

1500 New Hampshire Ave. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 483-6000

(800) 423-6953

You can’t beat this hotel’s fantastic Dupont Circle location. There are shops, restaurants, art galleries, and coffeehouses on every corner, along with glorious Beaux Arts buildings. The hotel was renovated, and rooms are clean, comfortable, and outfitted with all of the services you’d expect at a business hotel. It’s part of the Irish-owned Doyle Collection.

| The Georgetown Inn | $$$$ |

1310 Wisconsin Ave. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 333-8900

(888) 587-2388

If you’re coming to Washington, D.C., to soak up some history, you may want to stay in Georgetown, a neighborhood that found itself greatly divided during the Civil War. Land-holding gentry with roots in the South sympathized with their slave-holding counterparts even as federal officials struggled to hold the Union together. This 96-room inn sits in the center of Georgetown’s dining, shopping, and nightlife district. Guests can expect a comfortable stay with complimentary coffee and newspaper, and valet parking.

| The Hay-Adams Hotel | $$$$ |

16th and H Sts. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 638-6600

(800) 853-6807

A member of the Leading Hotels of the World, this opulent historic property is named for John Hay, Lincoln’s personal assistant and secretary of state under William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt, and author Henry Adams, a descendant of the noted political family. In 1884, Hay and Adams bought adjoining lots at 16th and H Streets on the site of the present-day hotel. The homes were later razed and, in 1927–1928, an Italian Renaissance–styled apartment hotel was constructed on the site. Outfitted with posh amenities like kitchens, elevators, and an air-conditioned dining room, the Hay-Adams House became the hotel of choice for traveling notables like Charles Lindbergh, Amelia Earhart, and Ethel Barrymore.

| The Henley Park Hotel | $$$–$$$$ |

926 Massachusetts Ave. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 638-5200

(800) 222-8474

Opened in 1918 as a luxury apartment building, the Henley Park was once home to famous Washingtonians like senators and congressmen. Today, this charming Victorian inn is a favorite of European travelers. Rooms are a bit dated, but its location near the Washington Convention Center puts the Henley Park in one of the most desirable locations in town. The on-site restaurant, Coeur de Lion, is also a draw, and the adjacent Blue Bar is a sure bet for mellow live entertainment. Guests enjoy amenities like express check-in, minibars, and health club privileges. Because it’s located so close to the Washington Convention Center, rates are always higher during big conventions.

| Hotel Harrington | $$$–$$$$ |

11th and E Sts. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 628-8140

(800) 424-8532

This no-frills, basic hotel is ideally located in the heart of downtown, just a few blocks from the National Mall, the White House, and the Penn Quarter arts and entertainment district.

| Hotel Lombardy | $$$$ |

2019 Pennsylvania Ave. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 828-2600

(800) 424-5486

It’s nothing fancy, but this inn-like hotel’s central location puts it within walking distance of Georgetown, Dupont Circle, and the White House, along with a couple of Metro stations. Rooms are equipped with kitchenettes, minibars, and other amenities.

| Hotel Monaco | $$$$ |

700 F St. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 628-7177

(800) 649-1202

The landmark 1842 Tariff Building that once housed the nation’s first General Post Office is now the stunning, 183-room Hotel Monaco. Operated by the Kimpton Hotel Group, the Monaco blends the building’s historic character and classic marble elements with chic, stylish, and colorful decor. During the Civil War, the hotel’s Paris Ballroom is believed to have been used as an operating room for wounded soldiers; guests and event-goers have reported hearing whispered voices that linger to this day. While there’s scant evidence to support these claims, there’s no doubt that many a distraught bride and mother came here to await news of her loved one’s whereabouts. While the building was undergoing renovation between 2001 and 2003, a construction worker reported seeing the figure of a woman in Civil War attire anxiously pacing in the building’s courtyard. Like Washington, D.C.’s other Kimpton hotels, the Monaco warmly welcomes pets (and even lets you borrow a goldfish for companionship, if you like), and offers a complimentary wine hour.

| Maison Orleans Bed and Breakfast | $$$$ |

414 5th St. SE

Washington, D.C.

(202) 544-3694

www.bbonline.com/dc/maisonorleans

Just six blocks from the Capitol, Library of Congress, and many of the capital’s best restaurants and attractions, Maison Orleans is a relaxing and unique oasis in the heart the city. Rates are fair and the ambience is cozy, but there are just three rooms—in addition to furnished one-bedroom and studio apartments.

| The Melrose Hotel | $$$$ |

2430 Pennsylvania Ave. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 955-6400

(800) MELROSE

It’s easy to feel at home here. After all, this West End hotel is another D.C. hotel fashioned out of a former apartment building. The Melrose’s rooms are cheery and spacious, decorated with classic and contemporary touches. There’s a Metro station right around the corner, and Georgetown and Dupont Circle are just a few blocks away.

| Morrison-Clark Inn | $$$–$$$$ |

11th St. and Massachusetts Ave. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 898-1200

(800) 332-7898

Like its sister property, the Henley Park, the Morrison-Clark is a gracious Victorian property just blocks from the Washington Convention Center. Rooms are charming, if a little tired, and outfitted with modern amenities like free wireless Internet, data ports, and complimentary newspapers. The Morrison-Clark Restaurant is a popular choice for romantic dinners, and the hotel’s garden room and courtyard are well suited for weddings.

| The Willard InterContinental Washington | $$$$ |

1401 Pennsylvania Ave. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 628-9100

(800) 827-1747

www.washington.intercontinental.com

There’s no hotel in the nation’s capital that boasts quite as rich a history as the Willard. In February 1861, representatives from 21 of the 34 states met at the Willard in an effort to avert the pending war. A plaque on the hotel’s Pennsylvania Avenue entrance honors these valiant efforts. Amid countless assassination threats, Lincoln was smuggled into the hotel after his election and prior to his inauguration in March 1861. His folio is on view in the history gallery. During the Civil War, the hotel was a gathering place for both Union and Confederate sympathizers. As a guest at the hotel, Julia Ward Howe wrote the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” as she listened to Union troops march past her window, playing “John Brown’s Body.” Actor John Wilkes Booth also frequented the Willard, making several visits in the weeks leading up to the Lincoln assassination. Legend has it that Ulysses S. Grant coined the term “lobbyist” here, referring to the favor-seekers who bothered him as he savored cigars and brandy in the hotel lobby. Outfitted with all of the posh amenities you’d expect in a fine luxury hotel, the Willard is located next to the White House and footsteps from the National Mall.

| Windsor Park Hotel | $$$ |

2116 Kalorama Rd. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 483-7700

(800) 247-3064

If the price doesn’t attract you to this pleasant, family-friendly inn, the proximity to Washington, D.C.’s eclectic Adams Morgan and Dupont Circle neighborhoods should. The hotel’s 43 simply furnished guest rooms come with a small refrigerator, newspaper, and complimentary continental breakfast.

| Woodley Park Guest House | $$$$ |

2647 Woodley Rd., NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 667-0218

(866) 667-0218

Formerly known as the Connecticut-Woodley Guest House, this elegant, recently renovated district inn blends modern amenities (central air-conditioning, high-speed Web access, etc.) with the comfortable look of antiques in its 18 rooms and suites, at reasonable rates for its location. The owners also do their part to foster a sense of community; there’s always someone lingering in the kitchen for a chat, and all of the works of art that adorn the walls were created by former guests.

| Ben’s Chili Bowl | $ |

1213 U St. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 667-0909

Ben’s Chili Bowl doesn’t have any strong Civil War connections, apart from its proximity to the African American Civil War Memorial. Nevertheless, no Washington, D.C., dining guide would be complete without it. Opened in 1958, Ben’s has weathered neighborhood riots and decay and still it manages to attract throngs of customers for its signature dish: the chili half-smoke (that’s half hot dog, half sausage, served on a bun and doused in chili, onions, and mustard). Wash it down with a creamy homemade milkshake. You’ll find urban hipsters, government staffers, and longtime neighborhood residents gathered here.

| Bistrot du Coin | $–$$ |

1738 Connecticut Ave. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 234-6969

It’s nothing fancy, but locals love this lively Dupont Circle bistro. It’s open every day—including Thanksgiving and Christmas—and always seems to draw an eclectic crowd of young and old, gay and straight diners from the neighborhood and beyond. Feast on steamed mussels, decadent tartines, hanger steaks, and other French and Belgian classics.

| Blue Duck Tavern | $$–$$$$ |

Park Hyatt Washington

1201 24th St. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 419-6755

Chef Brian McBride has proven himself to be a master of regional cuisine at Blue Duck Tavern, which made a splash in the Washington, D.C., dining scene when it opened. Tasty creations like pork loin with bourbon-soaked peaches, rabbit terrine, delectable crab cakes, and thick-cut fries cooked in duck fat, and homemade desserts like hand-churned ice cream and flamed chocolate bourbon pie have made it a crowd favorite. While the food is divine, the open kitchen is enough to make any chef turn green with envy.

| Brasserie Beck | $$–$$$$ |

1101 K St. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 408-1717

There’s a delightful trend in many of Washington, D.C.’s top new restaurants: Notable chefs are serving exquisite food in a comfortable, casual setting at reasonable prices. Brasserie Beck is a prime example. Chef Robert Wiedmaier earned acclaim among fine dining aficionados during a stint at Aquarelle at the Watergate before opening Marcel’s, his own restaurant, in the Foggy Bottom neighborhood. His second venture, Brasserie Beck, serves casual French and Belgian fare in a bistro setting. If the cuisine doesn’t bowl you over—and the housemade sausages and seasoned steamed mussels likely will—then the beer menu may be your downfall. True to his French-Belgian roots, Wiedmaier has a beer sommelier on staff and serves up an ever-changing lineup of more than 50 Belgian beers.

| Clyde’s of Georgetown | $$–$$$ |

3236 M St. NW

Washington, D.C.

202-333-9180

Clyde’s is a Washington, D.C.–area favorite with locations in Georgetown, downtown, and in the Maryland and Virginia suburbs. You can count on consistently good American fare made from fresh, local ingredients and served in a casual, distinctly American setting. Burgers, salads, chicken sandwiches, and crab cakes are always on the menu, but you can expect lighter salads and berry-laden desserts in the summer months and heartier stews in the colder months. There’s another D.C. location in Chinatown at 7th and G Streets NW.

| Filomena | $$$$ |

1063 Wisconsin Ave. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 338-8800

(888) FILOMENA

When you pass by this quaint Georgetown eatery, you’re apt to see the “pasta mamas” at work in the window preparing fresh noodles and stuffed pastas. It’s a hint of what’s to come inside the restaurant—fresh Italian creations and a cozy, homelike atmosphere. Bill and Hillary Clinton were known to dine here during their White House days.

| Kinkead’s | $$$–$$$ |

2000 Pennsylvania Ave. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 296-7700

If you love seafood and aren’t afraid to pay a little more for fine preparation, great ambience, and perhaps even some celebrity-spotting, make a reservation at Kinkead’s. Though it opened more than a decade ago, Kinkead’s still draws crowds. Regional delicacies like soft-shell crabs and skate wings are must-tries, and even New Englanders will appreciate Boston-born chef Robert Kinkead’s take on the lobster roll.

| Lauriol Plaza | $$$–$$$$ |

1835 18th St. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 387-0035

Lauriol Plaza is a longtime favorite for fresh Mexican cuisine. The zesty grilled fajitas and cheesy enchiladas are consistently good and the margaritas never disappoint, but the real draw here is the huge upstairs patio. Overlooking 18th Street between Dupont Circle and Adams Morgan, it’s a popular gathering spot on breezy afternoons and warm evenings.

| Lebanese Taverna | $ |

2641 Connecticut Ave. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 265-8681

Lebanese Taverna is another Washington, D.C., institution. It started as a single restaurant in Washington, D.C.’s Woodley Park neighborhood but has since expanded to additional locations in Virginia and Maryland. The family-owned Middle Eastern restaurant is always a sure bet for tasty moussaka, kebabs, shwarma, and plenty of vegetarian favorites.

| Martin’s Tavern | $$–$$$$ |

1264 Wisconsin Ave. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 333-7370

History buffs love Billy Martin’s Tavern, the oldest establishment of its kind in Georgetown. Opened in 1933, the Martin family is now on its fourth generation of restaurant owners. It’s here that John F. Kennedy proposed to Jackie in Booth #3, while Richard Nixon preferred Booth #2. Lyndon Johnson and Alger Hiss were also regulars, as was Madeleine Albright. You won’t be disappointed by the traditional American dishes nor the lively mix of tourists and neighborhood residents that pack the restaurant most nights of the week. It’s open daily for lunch and dinner.

| The Monocle | $$$$ |

107 D St. NE

Washington, D.C.

(202) 546-4488

A favorite of members of Congress and other Capitol employees, this family-owned, downtown Washington institution was the first white-tablecloth restaurant on Capitol Hill. Though new competitors have entered the marketplace, it’s still a favorite, serving up traditional American dishes in an elegant dining room or more casual bar. Try the signature roast beef sandwiches; it’s easy to see why John F. Kennedy would order them for special delivery to the White House.

| The Occidental | $$$$ |

1475 Pennsylvania Ave. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 783-1475

This 100-year-old restaurant is steeped in history. Next door, there’s the Willard Hotel, and the White House sits just beyond. Inside, the restaurant is decorated with black-and-white photos of the presidents, politicos, and celebrities who have dined at The Occidental throughout the century. You’d expect to find fine American fare on the menu, and you won’t be disappointed … nor will you be bored. Chef Rodney Scruggs works wonders with natural, locally procured ingredients to make delicious dishes like duck breast served with homemade spaetzle and braised rabbit ragu.

| Old Ebbitt Grill | $$–$$$$ |

675 15th St. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 347-4800

Established in 1856, Old Ebbitt Grill owns the distinction of being Washington, D.C.’s oldest restaurant. Although it no longer operates out of its original home, its classic furnishings and location just two blocks from the White House give it a historic feel. The restaurant prides itself on offering a fantastic oyster bar, though you also won’t go wrong with tasty crab cakes, trout crusted with parmesan cheese, and homemade pastas and soups. It’s known as a power breakfast spot during the week.

| 1789 | $$$$ |

1226 36th St. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 965-1789

If your historical tastes run into the Federal period as well, reserve a table at 1789. Fashioned after an elegant country inn, 1789 was named for the year in which nearby Georgetown University was founded. The cozy two-story row house is intimate and romantic; don’t be surprised to see a marriage proposal or an anniversary celebration happening at the table next to you. Executive chef Nathan Beauchamp, voted the metro area’s top rising culinary star by the Restaurant Association Metropolitan Washington, crafts masterful American fare from ingredients like pheasant, lobster, lamb, and crabs.

| Spices Asian Restaurant & Sushi Bar | $$ |

3333-A Connecticut Ave. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 686-3833

If your travels take you to Washington, D.C.’s Cleveland Park neighborhood—and a tour of Civil War forts very well might—treat yourself to a bite at Spices. In true Pan-Asian spirit, the restaurant serves tasty sushi, tempting curries, tasty pad thai, and classic Chinese dishes, all at affordable prices.

| The White Tiger | $–$$$ |

301 Massachusetts Ave. NE

Washington, D.C.

(202) 546-5900

There’s a lot to like about this Capitol Hill eatery, which focuses on northern Indian creations. Flavorful biryanis and tandoori dishes are served on gold platters, and, as you’d expect in an Indian restaurant, there are ample vegetarian options. In the summer, diners flock to the outdoor patio, which twinkles with white lights. One of the most attractive things about this neighborhood favorite: the prices.

| Wok ’N Roll | $–$$ |

604 H St. NW

Washington, D.C.

(202) 347-4656

There’s a good reason we’re including a quirky Chinatown restaurant with a funny name among our picks. In 1865, Mary Surratt operated a boardinghouse in the building that now houses Wok ’N Roll. It’s here that John Wilkes Booth met Surratt’s son, John, and other conspirators in the plot to assassinate the president. Many of the restaurant’s patrons don’t know the building’s significance; they’re here for the extensive menu of Chinese and Japanese creations, refreshing bubble teas, and sushi during happy hour.