Fredericksburg/Spotsylvania: Before Richmond

Only “Pickett’s Charge” on the third day at Gettysburg compares with the horrible bloodletting that took place before Marye’s Heights, above Fredericksburg, Virginia, on December 13, 1862. The Confederate shredding of one wave of blue-coated Yankees after another topped off the failure of yet another Army of the Potomac commander, this time heavy-whiskered Major General Ambrose Burnside.

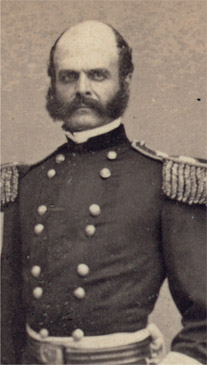

Major General Ambrose Burnside

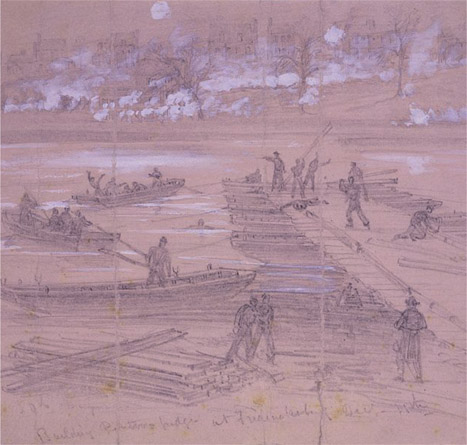

The fourth commander (including two stints by George B. McClellan) of the Union’s mightiest army, Ambrose Burnside inherited command from his old friend McClellan on November 7, after the latter general’s mediocre performance during and after the Battle of Antietam. Hoping to strike General Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army again before the arrival of winter, the burly Rhode Islander marched his massive, 130,000-man force south to Falmouth, Virginia—lost three weeks waiting for pontoon boats to arrive—then continued toward Fredericksburg, where Lee’s army was encamped. Union engineers spent December 11 stretching their pontoon bridges across the Rappahannock River (which ran northwest to southeast), while Yankee cannon lobbed shells over them and into the city, on the opposite shore. The following day, while Burnside reconnoitered and discussed with his senior commanders his plan of attack, thousands of his restless foot soldiers marched into Fredericksburg and looted it.

Union engineers constructing pontoon bridges across the Rappahannock River, December 11, 1862

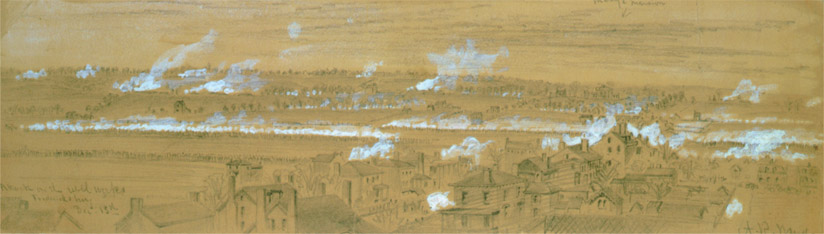

With his army stretched roughly north to south beyond the fields west of Fredericksburg, Robert E. Lee had a number of advantages: supportable interior lines, high ground, and for the men in his center, an almost-unassailable position behind a 400-foot stone wall along the crest of Marye’s Heights, above the town. Having lost the initiative and any hope of surprise, Burnside would have to count on sheer numbers: he had a 2–1 edge in manpower. For the Federals on December 13, there would be no elaborate feints; no flanking movements or surprise cavalry assaults—only power.

But as at Antietam and other battlefields, the Union commander nullified his advantage through inefficient—and, eventually, suicidal—deployment. Hoping to nail down Lee’s right while he hammered the Virginian’s left-center, Burnside ordered left-wing commander Major General William Franklin to launch an attack. But Franklin’s small-scale, early-afternoon assault petered out in the face of a vigorous Confederate response.

The attack on the Rebel positions in Fredricksburg on December 13, 1862

For the shivering, blue-garbed infantrymen of Major General Edwin Sumner’s right wing, meanwhile, a hideous nightmare had begun. All afternoon, regiment after regiment filed through the streets of Fredericksburg, formed up, and trudged up the slowly ascending, half-mile of ground toward Marye’s Heights. Confederate cannon blazed away. By the hundreds, astonished Confederate infantrymen lay their rifles across the stone wall and pulled triggers. It was a perfect shooting gallery. Only Brigadier General Thomas Meagher’s vaunted Irish Brigade managed to stagger within shouting range of the Confederate lines. Remembering the scene years later, one Union officer, Josiah Favill, wrote “there was no romance, no glorious pomp, nothing but disgust for the genius who planned so frightful a slaughter.”

Night fell. On into December 14—as thousands of bleeding and freezing Yankee soldiers lay on the hilly turf below Marye’s Heights—a heartsick Burnside pondered another attack, this time with himself at its head. Finally talked out of it, he arranged for a belated truce to bury the dead and collect the wounded, and then ordered a withdrawal back across the river.

For the stunned Army of the Potomac, the headaches were not quite over. Resolving to make up for the devastating setback by surprising Lee from the rear, Burnside ordered a looping march around Lee’s left across the Rappahannock. Campaigning at this time of year was hard enough with the onset of rain and snow that now swamped Burnside’s army, freezing soldiers and halting the endless Union wagon trains in feet of frosty mud. Still, soldiers retained their sense of humor, even coming up with a poem about their plight:

Now I lay me down to sleep

In mud that’s many fathoms deep;

If I’m not here when you awake,

Just hunt me up with an oyster rake.

Unsympathetic witnesses derided the Union columns as they struggled, shivering, down icy roads. With his doomed movement already being laughed off as the “Mud March,” Burnside called it off on January 25. For his used-up troops, the long, 1862 campaigning season was at a merciful end. Two days later, so was Ambrose Burnside’s reign as Army of the Potomac commander.

Having deposed the unfortunate Burnside, Abraham Lincoln turned to Major General Joseph Hooker, a capable, hard-fighting, and hard-drinking 48-year-old veteran of corps command who had served under his predecessor at Fredericksburg. Hooker immediately replaced Burnside’s unwieldy Grand Division army structure with the more-traditional corps setup, and reorganized the long-neglected Union cavalry into a single command under Major General George Stoneman. (Major General Alfred Pleasanton would replace Stoneman in June.)

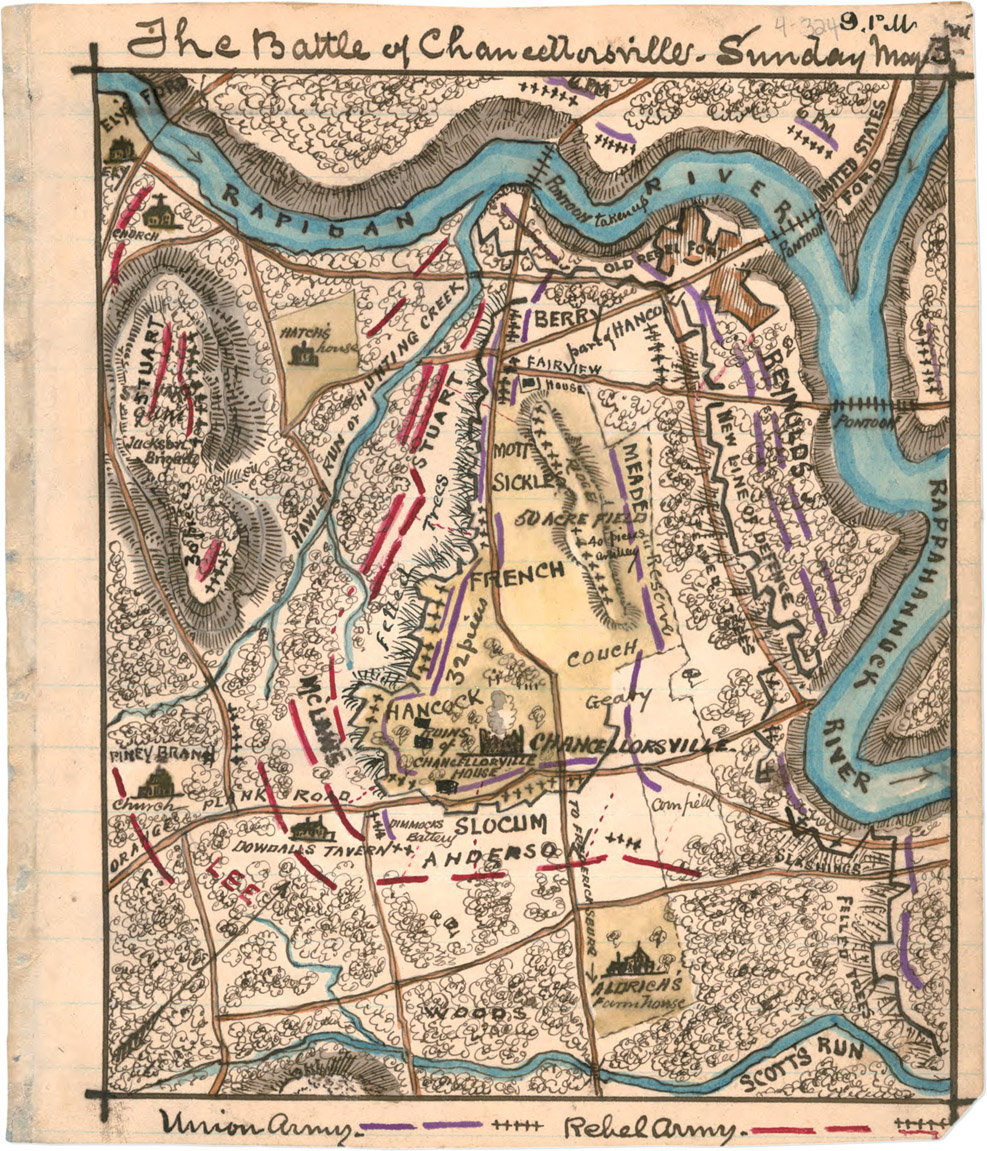

Map of the Battle of Chancellorsville, May 3, 1863

Rested after a winter in camp, Hooker’s Army of the Potomac opened the 1863 campaign season in stunning fashion. Sending Major General John Sedgwick and 30,000 Federals to keep Lee busy at Fredericksburg, and Stoneman’s cavalry raiding to the south, Hooker crossed the Rappahannock with 65,000 men and swung around behind Lee. The surprised and shorthanded Lee (elements of James Longstreet’s corps had been detached and sent south to Richmond) found himself trapped between the two halves of Hooker’s massive army. On April 30, Hooker’s staff confidently announced to the army:

It is with heartfelt satisfaction the commanding general announces to the army that the operations of the last three days have determined that our enemy must either ingloriously fly, or come out from behind his defenses and give us battle on our own ground, where certain destruction awaits him.

Lee was certainly not about to fly anywhere. Never afraid to try the unconventional, he divided his 53,000-man army, leaving just 10,000 to watch Sedgwick while he turned and marched 10 miles west to confront his latest Union opponent. He found Hooker’s army in line 2 miles east of the forbidding Wilderness—a tangled mess of undergrowth, trees, and briars through which a man could scarcely walk. Hooker made the first move on May 1, sending elements of three corps attacking east down local roads. Lee counterattacked, and as the fighting raged just west of the village of Chancellorsville, Hooker stunningly called a halt to his assault. Ignoring the protests of his corps commanders, Hooker pulled his flanks back and centered his new position at Chancellorsville. With his army dug in behind stiff fortifications, his position was formidable. His reasons for giving up his momentum and the initiative to Lee—the clear underdog in this contest—have never been made clear. The normally aggressive army commander apparently told one subordinate that he had lost confidence in Hooker. Whatever the reason for his decision, it opened the door for the most famous flank attack of the war. After discussing it with Lee, Stonewall Jackson and 26,000 Confederates set out early on May 2 to spring a surprise attack on Hooker’s right flank, which scouting Rebel cavalry had found unprotected. The absence of most of Stoneman’s Yankee cavalry—still missing to the south—was a blessing. Still, it was a risky plan; should Hooker change his colors and attack, Lee, with just 17,000 men, would be hard-pressed to escape Hooker’s blue-coated hordes.

Aside from some skirmishing with a portion of Jackson’s flanking party, Hooker did not attack. Neither he nor 11th Corps commander, Major General Oliver Otis Howard, seemed to be aware of what was brewing on their right. Howard found out at about 5:30 p.m., when the piercing Rebel yell filled the ears of his shocked 11th Corps men as they cooked up their rations. Bullets screamed by, followed by Jackson’s divisions. Dropping their food, Yankees bolted from their camp at top speed, their pursuers hard on their heels. The fighting on the Union right continued past dusk, as Yankee reinforcements fought to stem the slowing Confederate tide.

For the Confederate Army, the good news of the day was tempered by a horrifying report that Jackson had been seriously wounded. Reconnoitering under the moonlight, the corps commander had been mistakenly shot three times by his own soldiers. He was out of the fight; cavalryman J. E. B. Stuart took command of his corps. Informed of Jackson’s injuries by a junior officer, a troubled Lee replied: “Ah, Captain, any victory is dearly bought that deprives us of the services of General Jackson even for a short time.”

May 3 saw Hooker’s army tightening into a loop-shape with its flanks extended toward the Rapidan and Rappahannock Rivers. Hooker—knocked senseless by the concussion of an exploding shell—had little to do with the day’s fighting, during which Lee, Stuart, and dominating Confederate artillery compressed the Union lines. Only the news of John Sedgwick’s approach from the east stalled Lee, who detached a force to deal with the oncoming Yankees. Sedgwick, who had overrun Jubal Early’s Marye’s Heights defenders and chased him south, was himself now repulsed at Salem Church.

The following day, Lee led some 20,000 men east to dispose of Sedgwick, who retreated carefully north over the Rappahannock. The recovered Hooker—whose manpower advantage in the absence of Lee offered an opportunity to wipe out Stuart—did little but prepare to retreat. By noon on May 6, his army was back north of Rapidan, and the Chancellorsville Campaign was over, with Lee’s Confederates—again—the clear winner. Each side had lost more than 1,600 men killed. The loss of Jackson, who after losing an arm to amputation would succumb to pneumonia on May 10, particularly stunned the South. Jackson’s loss would be hard to overcome. But with conditions otherwise favorable for something audacious, Lee began to prepare for an invasion of the North.

The Rebel Yell

Of the myriad symbols and images of the old Confederacy, the rebel yell is perhaps the one most widely known yet most misunderstood. This particular battle cry was first heard at the First Manassas (First Bull Run), shortly after the war had begun. The originator of this cry was none other than the revered Brigadier (later Lieutenant) General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson (who earned his nickname in this very same battle). As Union infantry approached his Virginians, he rode calmly down the line of battle and gave his order: “Hold your fire until they’re on you. Then fire and give them the bayonet. And when you charge, yell like furies!” Minutes later, the “weird halloo of the rebel yell” (as Shelby Foote put it) was heard for the first time, as 20,000 Confederate soldiers swept the Union Army from the field.

A Union survivor of that battle later recalled, “There is nothing like it on this side of the infernal region. The peculiar corkscrew sensation that it sends down your backbone under these circumstances can never be told. You have to feel it.”

There are no known recordings of an actual full-volume rebel yell, the nearest approximation being a snippet of high-pitched “yipping” recorded on a 1920s-era movie about Civil War veterans. These men were in their 70s and 80s and obviously not in the prime of life or health anymore, so the sound was more reminiscent of a soft call to one’s dog rather than a fear-inducing battle cry. One aged veteran, noting the rather weak attempt at the sound, leans toward the camera and, with a wink in his eye, explains, “That’s the famous rebel yell!”

From scattered descriptions, it is apparent that the familiar “yee-haw!” heard from the stands at college football games is not the actual cry; many veterans compared it to a lusty and truly frightening version of a fox-hunter’s yelp. One of the better descriptions comes from notes taken at an 1891 veterans convention in Memphis, when the widow of Admiral Raphael Semmes asked Captain Kellar Anderson (of the famed Kentucky Orphan Brigade) to let her hear a rebel yell. Anderson gave a rather lengthy reply, starting with a description of the hellish action around Snodgrass Hill at the battle of Chickamauga. Then he went on:

There they go, all at breakneck speed, the bayonet at charge. The firing appears to suddenly cease for about five seconds. Then arose that do-or-die expression, that maniacal maelstrom of sound; that penetrating, rasping, shrieking, blood-curdling noise, that could be heard for miles on earth, and whose volumes reached the heavens; such an expression as never yet came from the throats of sane men, but from men whom the seething blast of an imaginary hell would not check while the sound lasted. The battle of Chickamauga is won.

Dear Southern mother, that was the Rebel yell, and only such scenes ever did or ever will produce it.

Even when engaged, that expression from the Confederate soldier always made my hair stand on end. The young men and youths who composed this unearthly music were lusty, jolly, clear-voiced, hardened soldiers, full of courage and proud to march in rags, barefoot, dirty and hungry, with head erect to meet the plethoric ranks of the best equipped and best fed army of modern times. Alas! Now many of them are decrepit from ailment and age, and although we will never grow old enough to cease being proud of the record of the Confederate soldier, and the dear old mothers who bore them, we can never again, even at your bidding, dear, dear mother, produce the Rebel yell. Never again; never, never, never.

Hailed by some as the Union’s savior, Ulysses S. Grant returned to the East during the spring of 1864 to take command of all Union armies. His victories out West had helped secure the Mississippi River for the Union; now he had been charged with bringing Confederate General Robert E. Lee to heel. Eastern veterans grown skeptical by the repeated failure of much-ballyhooed new commanders accepted the Western hero with hope. “If he succeeds, the war is over,” a Massachusetts captain wrote. “For I do assure you that in the hands of a General who gave them success, there is no force on Earth which would resist this army.”

Grant’s plan, basically, was to attack on all fronts. From Tennessee, Major General William T. Sherman would slash through Georgia, destroying Confederate supplies, communications, and transportation. In the East, Major General Benjamin Butler would march up the James River to pressure Richmond from the east. And while Franz Sigel (or his eventual successor Philip Sheridan) took control of the Shenandoah Valley, George Gordon Meade’s beleaguered Army of the Potomac would deal with Lee. Now a lieutenant general, Grant would travel with Meade’s army.

Battle of the Wilderness

Plan of the Battle of the Wilderness

Launching his Overland Campaign on May 4, Meade marched his 120,000 Yankees across the Rapidan River toward Lee’s 60,000 Confederates. Grant hoped to advance through the infamous Wilderness—a hellish tangle of woods and underbrush—and strike Lee on open ground before Lee could respond. The next day, however, elements of Meade’s right and Lee’s left collided on the worst possible terrain for fighting. The smoke of musketry saturated the area, blotting out the sky in the middle of the day. With cavalry and artillery of little use, infantry struggled to maintain any kind of formation—even to distinguish friend from foe just a few yards away. It was, one survivor testified, a “battle of invisibles against invisibles.” Another veteran remembered the “puffs of smoke, the ‘ping’ of the bullets, and the yell of the enemy. It was a blind and bloody hunt to the death, in bewildering thickets, rather than a battle.”

The bloody, terrifying fighting in the woods continued on May 6. Lee sent Lieutenant General Richard Ewell’s corps up the Orange Turnpike against Meade’s right, while Major General Winfield Scott Hancock and James Longstreet dueled back and forth on the Federals’ left. With no room for elaborate maneuver, the two armies slugged it out to exhaustion. Separated from their units by entangling thickets, enemy soldiers fought hand to hand with rifles and bayonets. “There wasn’t a tree … but what was all cut to pieces with balls,” one Yankee remembered, “and the dead and wounded was lying thick. It was an awful sight.” Badly wounded soldiers cut off from their units could only die alone. Others suffered a worse fate after darkness fell, perishing in fires set by heavy musketry.

Aside from costing the two armies a combined 28,000 casualties, the two-day fight settled nothing.

Map of Battlefield of Spotsylvania Court House

After two days of killing in the Wilderness, George Gordon Meade—putting into practice Grant’s relentless strategy—kept up the pressure on Robert E. Lee’s Confederates by sliding southeast toward Spotsylvania Court House. But units of Lee’s army beat him to the crossroads town and proceeded to fashion a mule-shoe-shaped line of virtually impregnable fortifications of logs, earth, and sharpened stakes that covered three sides of the town and protected the Confederates’ flanks. It was the sort of defense that less-determined Union generals would have done their best to avoid.

Near dusk on May 10, 5,000 Federals charged and carried a northern section of the Rebel works, before being forced to withdraw with heavy casualties. Encouraged, Grant sent a larger force—some 15,000 infantrymen with bayonets fixed—charging into the Rebel fortifications at 4:30 a.m. on May 12. The Confederates counterattacked from within their own lines, kicking off nearly a full day of back-and-forth struggle in a section of Lee’s lines that became known as the “Bloody Angle.” Under darkened skies and drenching rains, soldiers fought at close quarters: “Skulls were crushed with clubbed muskets,” one of Grant’s aides wrote, “and men stabbed to death with swords and bayonets thrust between the logs in the parapet which separated the combatants.”

Exhausted following the nightmarish slaughter of May 12–13, the two armies continued to probe and skirmish for another week until Grant and Meade—with Lee following—stepped off to the east, then the south, again, moving inexorably toward Richmond. In two weeks, Grant had incurred some 18,000 casualties (killed, wounded, or missing) compared to Lee’s 12,000, proving to some that he cared little for his soldiers and to others that he would fight until victory was won.

Grant and Meade continued moving south along the railroad, occasionally testing Lee’s sliding lines with little success. After several clashes along the North Anna River, Meade and Lee met at another crossroads called Cold Harbor, 10 miles northeast of Richmond. After a day of skirmishing on June 1, Grant prepared a massive frontal assault designed to exploit any weakness in Lee’s lines. Nearly a month of bloody stalemate had Grant chomping at the bit and determined to smash through the armies of his nemesis.

On June 3, three Union corps attacked Lee’s army, again barricaded behind impressive earthworks. The badly coordinated assault resulted in one of the war’s bloodiest (alongside Fredericksburg and Gettysburg) repulses, and 7,000 Yankee casualties in less than an hour. Grant’s month-long campaign resembled, to some, a horrific waste of life and expense. Once the Union’s best hope, Grant was now decried as a “Butcher.” “I do think there has been too much assaulting, this campaign!” one frustrated Federal declared. Major General Gouverneur K. Warren—a hero of Gettysburg who would later be relieved of his command—complained: “For thirty days now, it has been one funeral procession, past me; and it is too much!” Nearly four days passed as Lee and Grant haggled over the details of a truce for burial detail. Meanwhile, hundreds of suffering, wounded soldiers died on the battlefield.

Grant had learned his lesson. His next move—a lightning crossing of the James River to ensnare Petersburg—would leave both Lee and his detractors stunned.

Burial detail on the battlefield at Cold Harbor

Chatham

120 Chatham Lane

Falmouth, VA

(540) 371-0802

When you visit the Fredericksburg battlefields, be sure to make time to see Chatham, a Georgian-style mansion that served as the Union headquarters during the Battle of Fredericksburg. It’s also one of only three houses in the United States to have been visited by George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Abraham Lincoln. When war broke out, the house was owned by James Horace Lacy, a slave holder and Southern sympathizer who left his wife and children on the estate and joined the Confederate Army. Union forces took over the house in 1862, using it as a hospital to treat some of the 12,600 casualties from the disastrous defeat at Fredericksburg. Clara Barton and Walt Whitman were among the medical attendants. There’s a replica pontoon boat inside, fashioned after the ones used by the troops to cross the Rappahannock River. You can also catch a free movie, which illustrates the effects of the war on residents of the area.

Cold Harbor Battlefield and Visitor Center

Route 156 (5 miles SE of Mechanicsville)

(804) 226-1981

Although Cold Harbor is closer to Richmond and is part of Richmond National Battlefield Park, we’ve included it in this section due to its relationship to the other locations in the campaign. Cold Harbor has a visitor center that boasts an electric map program and exhibits depicting the 1862 Battle of Gaines’ Mill and the 1864 Battle of Cold Harbor. The battlefield itself features original entrenchments, which can be examined from numerous interpretive walking trails.

Cold Harbor National Cemetery

6038 Cold Harbor Rd.

Mechanicsville

Also a part of the battlefield (but administered by the Veterans Administration) is Cold Harbor National Cemetery, where more than 2,000 victims of area battles lay. On the cemetery grounds, there’s a masonry lodge designed by quartermaster Montgomery Meigs and monuments donated by the states of Pennsylvania and New York to honor their fallen soldiers. The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, erected in 1877, honors the 889 unknown Union soldiers who were killed and buried in trenches in and around Cold Harbor.

Ellwood

36380 Constitution Hwy.

Locust Grove

(540) 786-2880

http://www.nps.gov/frsp/ellwood.htm

Like Chatham, Ellwood was owned by the Lacy family at the start of the war and is now part of the battlefield park. While it lacks the grandeur of Chatham, it’s not without its historic significance. During the Battle of Chancellorsville, many of the wounded were treated here, including Confederate general Stonewall Jackson. His amputated arm is famously buried in the Lacy family cemetery on the house’s grounds. Union troops used Ellwood as a headquarters a year later during the Battle of the Wilderness.

Fredericksburg Area Museum and Cultural Center

1001 Princess Anne St.

Fredericksburg

(540) 371-3037

This community museum located in Fredericksburg’s 1816 Town Hall/Market Square building reaches beyond the Civil War to showcase the town’s colonial history, its ties to the railroad, and other themes. Artifacts like Confederate currency and officers’ uniforms and weapons help relate the town’s role before, during, and after the war.

Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park

120 Chatham Lane Fredericksburg

(540) 373-6122

Second only to Chickamauga and Chattanooga in terms of size, this military park is one of the most significant: It includes four important battlefields (including the Wilderness and Chancellorsville), two visitor centers (Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville), and four historic buildings. One of these structures is now the Stonewall Jackson Shrine, the small Chandler Plantation building in which Stonewall Jackson died on May 10, 1863. In addition to numerous walking trails and driving tours (with audiotape), the park often provides guided tours. Its two visitor centers offer 22-minute films.

A number of recent changes to the park have brought its battlefields closer than ever to their original appearance. During the summer of 2006, the National Park Service (NPS) set about restoring the “Sunken Road” and stone wall along Marye’s Heights. Along this battered old road (and behind this wall), Lee’s Confederates stood as they mowed down Ambrose Burnside’s Federals during the Battle of Fredericksburg. The park has also managed to acquire the land over which Stonewall Jackson launched his crushing flank attack on Joseph Hooker’s army at Chancellorsville, along with the site of James Longstreet’s flank attack in the Wilderness.

The park is open free of admission from dawn to dusk daily. Hours for the visitor centers vary by season. (Ask about the popular Kenmore and Washington Street Tour.) Rather than visitor centers, the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House Battlefields feature interpretive shelters where historians are often available (during warmer months) to answer questions.

Massaponax Baptist Church

5101 Massaponax Church Rd.

Fredericksburg

(540) 898-0021

Massaponax Baptist Church was just four years old when Union lieutenant general Ulysses S. Grant, Major General George Meade, and their staffs stopped there on May 21, 1864, following the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House. Grant had a number of the church pews carried outside, where he and his subordinates rested and plotted their next moves. Timothy O’Sullivan, one of the war’s most prolific photographers, subsequently captured the gathering in one of the war’s best-known sequence of images.

Often used as officers’ headquarters or as temporary shelter for passing soldiers, the church still bears visible signs (scrawled names and messages) of the soldiers’ presence. It is also still open for regular services, so call ahead before stopping in.

Spotsylvania County Museum

8956 Courthouse Rd.

Spotsylvania

(540) 582-7167

The Old Berea Church, constructed in 1856, now houses the Spotsylvania County Museum. While the small collection of local artifacts and genealogical records will be of most interest to local history buffs, the church bears the marks of shots and shells from the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, which raged nearby. Admission is free.

Spotsylvania Court House

9104 Courthouse Rd.

Spotsylvania

(540) 891-8687

Established in 1839, Spotsylvania Court House witnessed one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War, which marked the beginning of the fall of the Confederacy. The Court House stood at the intersection of Routes 613 and 208, guarding the shortest route to Richmond. The building sustained significant damage during the Civil War and was reconstructed in 1900, using the Doric columns of the original building.

White Oak Museum

985 White Oak Rd.

Falmouth, VA

(540) 371-4234

Housed in a one-room schoolhouse, the White Oak Museum’s collection includes a mix of Union and Confederate artifacts like reconstructed huts, bullets, belt plates, and buttons gathered from area battle sites. The museum is located on the original site of the White Oak School, which was burned and rebuilt in 1912.

Ghosts of Fredericksburg Tours

706 Caroline St.

Fredericksburg

(540) 710-3002

www.ghostsoffredericksburg.com

Offered on select Fri and Sat evenings in season, author Mark Nesbitt’s eerie tours trace the macabre past of a town considered the most haunted in America. The 80-minute tours are led by costumed guides who relate stories from Fredericksburg’s colonial and Civil War past. Reservations are strongly recommended.

Trolley Tours of Fredericksburg

(540) 898-0737

If you’ve got a short time to explore, leave your car at the hotel and climb on board the trolley. In an hour and 15 minutes, you’ll get a nice overview of downtown’s rich history and the nearby Civil War battlefields. The tour departs from the visitor center; hours vary by season.

| Kenmore Inn | $$$–$$$$ |

1200 Princess Anne St.

Fredericksburg

(540) 371-7622

A charming Old Town Fredericksburg inn, the Kenmore has nine rooms, all with private baths, and four with working fireplaces. The building itself dates to 1793 and claims members of George Washington’s family as its former owners. Despite the historic location, the rooms are outfitted with modern amenities like wireless Internet and flat-screen TVs. Guests enjoy a tasty cooked-to-order breakfast, featuring farm-fresh eggs, pancakes, and other classics. The inn’s fine-dining restaurant serves delectable American cuisine prepared by chef Josh Oleson.

| La Vista Plantation Bed & Breakfast | $$$$ |

4420 Guinea Station Rd.

Fredericksburg

(540) 898-8444

(800) 829-2823

Located just 2 miles from the Massaponax Baptist Church (where photographer Timothy O’Sullivan photographed Union generals Grant, Meade, and a host of others in May 1864), Ed and Michele Schiesser’s La Vista Plantation sits in the heart of Spotsylvania Campaign ground. Follow a long driveway to the 1838 farmhouse, whose spacious rooms and common areas are meticulously and tastefully furnished with antiques. Guests enjoy gracious hospitality and a tasty breakfast made with fresh brown eggs from one of the resident hens, along with amenities like central air, satellite TV, and VCRs, working fireplaces, big canopy beds, and even refrigerators. Those guests that simply can’t get enough of the Civil War can help themselves to books in the inn’s library. Rooms are rented by reservation only, so call ahead.

| On Keegan Pond Bed & Breakfast | $$–$$$$ |

11315 Gordon Rd.

Fredericksburg

(888) 785-4662

This cozy B&B is a good choice for Civil War travelers who prefer more of a bucolic setting. Artifacts found on its five-acre grounds indicate that Union scouts were on the grounds during the opening sequences of the Battle of Chancellorsville. The inn’s two rooms are clean and comfortable, furnished with antiques and equipped with central air, heat, and private baths.

| The Richard Johnston Inn Bed & Breakfast | $$$–$$$$ |

711 Caroline St.

Fredericksburg

(540) 899-7606

(877) 557-0770

If you’re looking for a historic place to stay in the heart of Old Town Fredericksburg, check into the Richard Johnston Inn. The inn’s seven rooms and two suites are charming and comfortable, furnished with antiques and big, comfortable beds. The top selling point, however, is the inn’s central location, with shopping, dining, and sightseeing options on its doorstep—and the visitor center just across the street.

| Schooler House Bed & Breakfast | $$$–$$$$ |

1303 Caroline St.

Fredericksburg

(540) 374-5258

If you want to mix in a little romance and elegance with your history, you can’t beat the Schooler House. Built in Victorian Italianate style in the town’s historic district, the house itself dates to the late 19th century. Period antiques and art decorate its two bedrooms, both of which come with private baths—and you might even happen upon a claw-foot bathtub. Period antiques are also found throughout the inn. Innkeeper Andi Gabler, an expert on local history, treats her guests to a healthy, generous breakfast spread, served on antique dishes and silver. On the grounds, you’ll also find a tranquil garden with a goldfish pond and waterfall that’s perfect for relaxing after a day of sightseeing.

| Wingate by Wyndham | $$–$$$ |

20 Sanford Dr.

Fredericksburg

(540) 368-8000

The Fredericksburg location of this growing chain (a division of Wyndham Hotels) warrants a visit for its value and convenience to the interstate. This 129-room hotel serves up a host of amenities for business travelers like a 24-hour business center and high-speed Internet, but leisure travelers will also enjoy the free local calls, indoor pool, and ample breakfast service. It’s clean and comfortable, an excellent home base for exploring the battlefields in and around Fredericksburg.

| WyteStone Suites | $$$–$$$$ |

4615 Southpoint Pkwy.

Fredericksburg

(540) 891-1112

(800) 794-5005

The 85-room WyteStone Suites is another example of a business hotel that provides a great value for tourists as well. Traveling families will especially benefit from the all-suite layout, indoor swimming pool, in-room refrigerator and microwave, and complimentary hot breakfast. There are also six wheelchair-accessible suites. It’s easy to spot from I-95, and there’s no shortage of quick service restaurants and shopping options nearby.

| Allman’s BBQ | $$ |

1299 Jefferson Davis Hwy.

Fredericksburg

(540) 373-9881

Allman’s unassuming exterior belies its reputation as Fredericksburg’s longtime king of Carolina-style barbecue. Its vintage 1954 interior sports the look of a classic diner, but it’s the food that fills barstools, and Mary “Mom” Brown’s ribs and coleslaw have been doing just that for 50 years. There’s a second drive-through location at 2022 Plank Rd.

| Bistro Bethem | $$$ |

309 William St.

Fredericksburg

(540) 371-9999

Blake and Aby Bethem’s chic, casual bistro offers an enticing seasonal menu, featuring fresh fish, wild game, and other tasty creations prepared with a Southern accent. Macaroni and cheese is prepared with Gruyère, fontina, and white cheddar and a hint of shallots. You can also nibble on house-made charcuterie plates and antipasto selections and treat yourself to heavenly desserts.

| Brock’s Riverside Grill | $$$ |

503 Sophia St.

Fredericksburg

(540) 370-1820

You can’t beat the ambience at Brock’s Riverside Grill. The comfortable, casual eatery is perched on the banks of the Rappahannock River. On the menu you’ll find delectable seafood and hand-cut steaks, along with an assortment of pastas, sandwiches, and salads. If you’re in the mood for dancing, stop by on a Thur, Fri, or Sat evening.

| Carl’s Frozen Custard | $ |

2200 Princess Anne St.

Fredericksburg

Ice cream lovers—and especially frozen custard lovers—won’t want to miss a stop at Carl’s, a local favorite since 1947. While there’s no food service here, you can easily make a meal of the chocolate, vanilla, and strawberry frozen concoctions churned in a 1940s-era Electro-Freeze ice-cream machine. It’s open daily from mid-Feb to mid-Nov.

| Eileen’s Bakery and Café | $ |

1115 Caroline St.

Fredericksburg

(540) 372-4030

If you’re staying in Old Town Fredericksburg, stop by Eileen’s for a cup of coffee and breakfast sandwich or warm mushroom popover on your way to see the sights. Or, pick up one of Eileen’s gourmet sandwiches or salads for a picnic lunch. In addition to classic turkey and ham creations, you’ll also find some inventive vegetarian options like a grilled asparagus sandwich served with roasted tomato mayo and curried mushrooms.

| Goolrick’s Pharmacy | $ |

901 Caroline St.

Fredericksburg

(540) 373-3411

For another retro dining experience, stop in to Goolrick’s pharmacy in downtown, home to the oldest operating soda fountain in the country. If you’re looking for a little nostalgia, you’ll find it in a thick, creamy milkshake, fresh-squeezed lemonade, or grilled cheese sandwich served in the back of this independent drugstore.

| J. Brian’s Tap Room | $$ |

200 Hanover St.

Fredericksburg

(540) 373-0738

Charles Dickens once stayed and dined in the historic hotel building that now houses J. Brian’s Tap Room. With its tall ceilings and hardwood floors, the restaurant blends in well with its historic location. Fare here is simple and satisfying: think burgers, steaks, and pizzas, perfectly paired with a beer or glass of wine.

| Olde Towne Steak and Seafood | $$$ |

1612 Caroline St.

Fredericksburg

(540) 371-8020

www.oldetownesteakandseafood.com

Established in 1981, Olde Towne Steak and Seafood is a Fredericksburg classic, consistently ranked among Fredericksburg’s top eateries. The name says it all: generous platters of lobster, shrimp, and other seafood creations, along with juicy steaks, tender chicken, and “surf and turf” selections. All entrees are served with a garden salad, potatoes, and fresh-baked sourdough bread.

| Ristorante Renato | $$$ |

422 William St.

Fredericksburg

(540) 371-8228

For delicious northern Italian cuisine, pull up a chair at Ristorante Renato, where you’ll find a tasty selection of home- made pastas and Mediterranean classics like gnocchi doused in veal ragu and eggplant parmesan. Finish it off with a delicious bite of tiramisu, spumoni, or cannoli. The 260-seat restaurant is ideal for parties and festive occasions, just footsteps from Fredericksburg’s historic core.

| Sammy T’s | $$ |

801 Caroline St.

Fredericksburg

(540) 371-2008

If you’re looking for a light and healthy dining choice, grab a table at Sammy T’s. The menu is packed with creative vegan and vegetarian creations like black bean cakes, apple and cheddar sandwiches, and a to-die-for bean and grain burger topped with sautéed mushrooms, peppers, tomatoes, and onions and smothered in cheese. The building itself dates to 1804; after the Civil War, Brigadier General Darrel Ruggles (Confederate States of America) lived here as he developed new innovations for the railroad.