Petersburg: Siege Warfare

Battle of Petersburg

Located 25 miles south of Richmond, Petersburg was a massive conduit through which railroads connected the Confederate capital with Virginia’s southern and western neighbors. With Petersburg in his pocket, a well-supplied and supported Union general could isolate and gradually squeeze the life out of Richmond’s defenders.

That is precisely what happened. After a month of vicious combat capped by the stunning June 3, 1864, reverse at Cold Harbor, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant suddenly drove south and over the James River in mid-June, putting the Army of the Potomac in place to grab Petersburg and isolate Richmond.

Between June 15 and 20, Major General P. G. T. Beauregard’s Rebel defenders—helped after the 17th by Robert E. Lee’s shifting army—repelled a series of Union attacks on the Petersburg fortifications. Resigning himself to a siege, Grant continued to probe and dig toward Lee’s lines, attacking Lee’s communications and transportation while stretching the Confederate trenches west. In July, Jubal Early’s raid up the Shenandoah Valley forced Grant to detach elements of two corps to Washington, but it made little difference.

Grant’s grip on their city tightened, and Petersburg residents struggled to find the bare necessities of life. Weary infantrymen dug in around Petersburg ducked shells and skirmished. Most were still trying to sleep on the morning of July 30 when Yankees lit a fuse beneath their trenches. Minutes later, the sizzling combustible ignited four tons of gunpowder, catapulting tons of earth, sandbags, logs, and lifeless soldiers toward the sky and ripping a gap in the Rebel lines southeast of town.

While Union batteries delivered a follow-up barrage of shells, shocked Confederate officers recovered from their surprise to shift troops into the hole in their lines, which Union regiments were rushing to expand. Botched orders and shoddy leadership turned this opportunity into disaster. Federals charged straight into the huge ditch created by the explosion, and they were quickly pinned in by howling Confederates. Reinforcements of the United States Colored Troops (USCT) fought bravely, as vicious hand-to-hand fighting turned into a near massacre. Federals fell by the score.

Union troops in the trenches at Petersburg

Blame for the disastrous “Battle of the Crater” fell on Ninth Corps commander Major General Ambrose Burnside, who had developed a nasty penchant for wasting the lives of his soldiers. Meanwhile, the siege continued. Booming Union artillery drove thousands of people into the hills, where they struggled to avoid shells and find enough food to survive in makeshift bunkers. On the inland side of the city, Confederate soldiers pinned down in miles of trenches fought their own battle to survive—enemy soldiers as well as hunger. Beyond the Rebel trenches were even more extensive Union pits, into which more men in blue seemed to pour each week.

Although Lee managed to keep Grant at bay throughout the fall of 1864, his army withered away during the winter. On March 25, 1865, Lee sent Major General John Gordon after a Union outpost to the east. Gordon briefly overran Fort Stedman, but could not hold it, and lost more than 3,000 men in the process.

By April 3, 1865, Petersburg, Virginia, was a dusty ghost town, pinned against the Appomattox River by hideously scarred landscape and Major General George Gordon Meade’s Union Army of the Potomac (now more often identified with General in Chief Ulysses S. Grant, who had made it his headquarters). Nearly 10 months of dirty, dusty siege had sealed the city’s fate.

On April 1, Union infantry and cavalry overwhelmed Confederate defenders west of the city at a crossroads called Five Forks. With his right flank turned, Robert E. Lee could do little when Grant attacked his lines a day later. Finally convinced of success, Grant attacked Lee’s thinly manned trenches west of the city late on April 2. Lee evacuated the remnants of his army and headed west, while Federals occupied Petersburg and, a day later, the Confederate capital. The war was all but over.

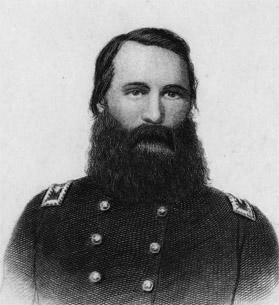

James Longstreet

General James Longstreet

Four years of war took their toll on James Longstreet, who was severely wounded in 1864 and widely blamed for the crucial Confederate defeat at Gettysburg in July 1863. For Robert E. Lee’s longest-serving corps commander, it only got worse at war’s end.

Born in South Carolina in 1820 and raised in Georgia, James Longstreet graduated from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1842. There he lived and studied with a number of future Civil War generals and began a lifelong friendship with Ulysses S. Grant. After service in the Mexican War and several years of frontier duty, Major Longstreet resigned from the army in May 1861. He subsequently accepted a commission as a lieutenant colonel in the Confederate States Army.

Between the June 25, 1862, clash at Oak Grove and the May 3, 1863, Battle of Chancellorsville, Longstreet and Thomas J. Jackson commanded the two corps of Robert E. Lee’s seemingly invincible Army of Northern Virginia. Without Jackson, who was mortally wounded at Chancellorsville, Lee was finally beaten at Gettysburg in July 1863. The stinging defeat ended his invasion of the North and spurred charges of insubordination against Longstreet, who had disagreed with Lee on tactics. The following May in Virginia’s tangled Wilderness, a Yankee bullet knocked Longstreet from the saddle, leaving Lee without his two best subordinates in his ongoing duel with Longstreet’s old friend, and now Union general in chief, Ulysses S. Grant.

By the time Longstreet returned to action in October 1864, Grant had Lee’s army in a stranglehold that could only end in submission. Near Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on April 9, 1865, Union Major General George Custer approached Longstreet under a flag of truce and demanded—in the name of Major General Philip Sheridan—the Confederate Army’s surrender. “I am not the commander of this army,” an irritated Longstreet replied, “and if I were, I would not surrender it to General Sheridan.” Later that day, Lee surrendered the army to Grant.

After the war, Longstreet’s acceptance of federal Reconstruction legislation, his willingness to accept Federal employment (including an appointment by President Grant as surveyor of customs for New Orleans, and a later stint as U.S. minister to Turkey), and, especially, his defection to Grant’s Republican Party, made him a prime target for ex-Confederates looking to cast blame. Longstreet’s slowness, they claimed, had cost Lee time and again—especially at Gettysburg, where the corps commander had waited too long to attack the Union left on July 2.

Longstreet defended his Civil War service in his memoirs; a few friends also came to his defense. In recent years, historians have restored to a large degree the general’s tarnished reputation, returning him to his place in Civil War memory as Lee’s “old war-horse.”

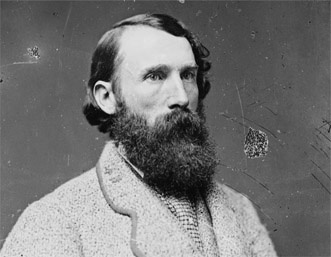

A. P. Hill

General A. P. Hill

Born in Culpeper, Virginia, in 1825, Ambrose Powell Hill graduated from West Point in 1847. After stints in Mexico and on various frontier posts, Hill, in March 1861, traded his U.S. Army commission for the colonelcy of a Confederate army regiment, the 13th Virginia. Promoted rapidly up to major general, Hill established himself as one of the South’s great fighting generals, with a knack for saving the day. At Antietam in September 1862, the timely arrival of Hill’s division on the battlefield south of Sharpsburg prevented a disaster brewing for the Confederates. After taking command of Robert E. Lee’s III Corps following the death of Stonewall Jackson, Hill fought at Gettysburg, the Wilderness, and Spotsylvania—proving to be better suited to a smaller command. In the predawn darkness of April 2, 1865, just a week before Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, a Union bullet killed Hill outside the trenches west of Petersburg.

Blandford Church

111 Rochelle Lane

Petersburg, VA

(804) 733-2396

www.petersburg-va.org/tourism/blandford.htm

This historic church was built in 1735, but abandoned in 1806 as the congregation drifted to a new downtown location. It regained prominence in 1901 when the Ladies Memorial Association of Petersburg began to rebuild the church as a Confederate Memorial. The association turned to each former Confederate state and solicited funds to create and install a Tiffany commemorative window to honor the fallen soldiers from that state. The adjacent cemetery was the site of the first Memorial Day celebration, held in June 1866 in honor of the 30,000 Confederate soldiers buried on the hillside.

Pamplin Historical Park and the National Museum of the Civil War Soldier

6125 Boydton Plank Rd.

Petersburg, VA

(804) 861-2408

(877) PAMPLIN

Pamplin Park is an absolute must-see. Since opening in 1994, this combination museum/battlefield has ranked among the nation’s most visited historical sites. Continuous expansion (now 422 acres) coupled with state-of-the-art exhibits and educational programs have since made it the top Civil War attraction in the country.

The park is named for its benefactors—Robert B. Pamplin Sr. and Dr. Robert B. Pamplin Jr.—who in 1991 purchased a parcel of land that bore remnants of the Confederate earthworks overrun by Ulysses S. Grant’s Union soldiers on April 2, 1865. A second purchase, of the adjacent Tudor plantation, was made in 1994; restoration of this home (once used as a headquarters by Confederate general Samuel McGowan) was completed two years later. In 1999, Pamplin Park’s title grew a little longer with the opening of the National Museum of the Civil War Soldier, a fantastic, 25,000-square-foot facility that beautifully countered the park’s natural features with state-of-the-art exhibits and visitor services. Even more recently, the park has opened reconstructed slave quarters on the Tudor Hall Plantation, hiking trails, the Banks House (Grant’s headquarters), and a new Education Center.

Strengths of the park include its superb staff and the opportunities for visitors to learn about the Civil War in several different ways, including hands-on outdoor exhibits; living history demonstrations; interpretive, audio-aided museum exhibits; and classes designed for all age groups. Excellent permanent exhibits include “Duty Called Me Here,” “A Land Worth Fighting For,” “The Battle of the Breakthrough,” and “Slavery in America.” Visitors with children, meanwhile, will want to consider contacting the park about its new Adventure Camp, a fun but educational introduction to soldier life for folks of all ages.

Petersburg National Battlefield

5001 Siege Rd.

Petersburg, VA

(804) 732-3531, ext. 200

The ugly, daily struggle at Petersburg was unlike the fighting on any other battlefield, ensuring that its earthen remnants would found a park like no other. Stretching more than 30 miles from the Union supply depot at City Point to the Five Forks Battlefield west of the city, this remarkable park includes three visitor centers along its 13-stop driving tour. The foremost of these, the Eastern Front Visitor Center, is a mini museum, using exhibits and interactive displays to tell the military and civilian story of the nine-and-a-half-month siege.

Highlights of the park include the City Point headquarters cabin used by Grant during the siege; a massive, 13-inch seacoast mortar (like the terrifying “Dictator” used here by Federals); outstanding examples of fieldworks; the Elliott’s salient entrance to the Petersburg mine shaft; the original crater site; and endless earthworks.

The Siege Museum

15 W. Bank St.

Petersburg, VA

(804) 733-2404

www.petersburg-va.org/tourism/siege.htm

The Siege Museum takes a closer look at civilian life in the town of Petersburg before, during, and in the aftermath of the Civil War. Much of the collection focuses on how the town suffered and persevered during the 10-month siege, the longest of its kind in American military history. As you tour the museum, you can also catch an 18-minute film outlining the town’s involvement in the Civil War, narrated by Joseph Cotton.

| High Street Inn | $$–$$$ |

405 High St.

Petersburg, VA

(804) 733-0271

The Queen Anne–inspired High Street Inn was built just before the dawn of the 21st century and has enjoyed quite a colorful past. Built as a residence, it was later used as a funeral home and a Veterans of Foreign War outpost before becoming a B&B more than 20 years ago. Check in to one of the six spacious guest rooms, each of which bears the name of a historic street or character in Petersburg history. You’ll be treated to hospitable touches like lemonade and cookies delivered to your room and generous breakfast service.

| Ragland Mansion Guesthouse | $$–$$$ |

205 S. Sycamore St.

Petersburg, VA

(800) 861-8898

Italianate in design, the grand Ragland Mansion stands out in the historic Poplar Lawn district. The antebellum mansion survived the siege and was expanded on by railroad tycoon Alexander Hamilton. Its seven rooms (plus a suite) all feature air-conditioning, private baths, queen- or king-size beds, and TV.

| Walker House Bed & Breakfast | $$–$$$ |

3280 S. Crater Rd.

Petersburg, VA

(804) 861-5822

This circa-1815 mansion boasts four bedrooms named for the four seasons, each of which is equipped with cable TV, wireless Internet, and private bath. Each room is decorated to reflect its namesake season. Even if the inn is full, however, you’d never know that you were sharing it with four other parties. Help yourself to snacks and beverages, available ‘round the clock in a second-floor kitchenette. Wake up to a breakfast of fresh waffles, sausages, and other tasty creations. The house itself is not without its own Civil War connections; it was used for the inquiry after the Battle of the Crater featured in the movie Cold Mountain.

| Alexander’s | $$ |

101 W. Bank St.

Petersburg, VA

(804) 733-7134

Located in historic Old Towne Petersburg, this charming and friendly little restaurant offers Italian and Greek cuisine, including gourmet sandwiches and salads and flavorful specialties like souvlaki, roasted leg of lamb, lasagna, and manicotti.

| Andrade’s International Restaurant | $$ |

7 Bollingbrook St.

Petersburg, VA

(804) 733-1515

Recommended by local innkeepers, Andrade’s is known for serving Peruvian and Spanish fare like delicious garlic shrimp and seasoned steaks. On a pleasant afternoon, you can also sit outside and enjoy dining alfresco.

| Jimmy’s Grille | $$ |

16 Goodrich Dr.

Petersburg, VA

(804) 733-3181

This local favorite is tucked away from the main strip, but the rewards are worth it if you seek it out. Feast on lavish breakfasts like omelets and pancakes or lunch and dinner entrees like barbecued pork sandwiches or classics like meatloaf and fried chicken featured in the daily special.

| King’s Famous Barbecue | $$ |

2910 S. Crater Rd.

Petersburg, VA

(804) 732-0975

A Petersburg institution, opened in 1946, locals and visitors know King’s for its legendary barbecue, with pork, beef, ribs, and chicken constantly smoking in an open pit in the pine-paneled restaurant dining room. The meat is flavorful when served straight from the pit or seasoned with King’s vinegar-flavored sauce. That’s not the only thing on the menu, though; there’s also southern-fried chicken, ham steak, and fresh seafood.

| Nanny’s | $$ |

11900 S. Crater Rd.

Petersburg, VA

(804) 733-6619

Bring your appetite to Nanny’s, where you’ll find one of the most generous, ample buffet spreads in town. The menu varies every day, but you can count on fried chicken, barbecued beef, pulled pork, fried fish, and other Southern classics.