North Carolina: Outer Banks to the Last Great Battle

At the beginning of the “secessionist crisis” after the election of Lincoln in 1860, North Carolina was not overwhelmingly in favor of leaving the Union, as opposed to the position held by its namesake to the south. Although a primarily agricultural state, there were relatively few slaves in the state, which was marked more by disparate, isolated elements mostly either neutral or outright hostile to both slavery and secession. Several meetings across the state in late 1860 only produced more evidence that if secession was inevitable, it would be done without widespread support.

As the talks raged, South Carolina declared itself free and independent on December 20, the first state to openly declare secession from the Union. In North Carolina the only large public celebration was a mass gun firing in Wilmington, a city noted for its strong support of secession. This act touched off even more heated debate across the state, the majority of citizens tending to support staying within the Union but radically opposed to any force being used to keep any state within it. In the middle of this continued crisis, the state legislature disbanded for the Christmas holidays.

With most of the politicians safely out of the way, staunch secessionists in Wilmington went into action. On December 31 the citizens of that coastal city wired Governor John Willis Ellis of North Carolina, asking permission to seize nearby Forts Caswell and Johnston, as they constituted a “threat” to access to the city via the Cape Fear River. Ellis refused, but the citizens went ahead and seized the forts based on an erroneous rumor that U.S. troops were on the way to garrison them. Ellis then immediately demanded that the Carolinians evacuate the posts and, when they had removed themselves, sent a letter of apology to President James Buchanan (Lincoln had been elected but not yet sworn in at the time).

All through the winter and early spring of 1861, Ellis continued to act in an equally conservative manner, backed up by a February 28 popular vote against a secession convention. Even the secession of six fellow Southern states and the bombardment of Fort Sumter at Charleston on April 12 and 13, 1861, did not sway Ellis from his Unionist stance. The deciding factor, however, was an April 15 letter from Lincoln asking Ellis to provide two regiments of militia to “suppress the Southern insurrection.” Ellis regarded such a request as a violation of the 10th Amendment to the Constitution, which addresses the rights of the individual states, and “a gross usurpation of power” on Lincoln’s part.

Ellis immediately ordered the seizure and occupation of “Federal” (or Union) installations and forts throughout the state and called for a secession convention. On May 20 the convention met and, by the day’s end, had both adopted an ordinance of secession and ratified the Confederate constitution. North Carolina was officially separated from and at war against the United States government.

Although General in Chief Winfield “Old Fuss and Feathers” Scott had warned at the very beginning that the war with the South would be long and bloody, most military personnel and civilians alike, North and South, scoffed at the 75-year-old general’s words. The initial rush of volunteers was fueled partially by the desire to see combat “before it’s all over,” and 90-day enlistments of both individuals and militia companies were common on both sides.

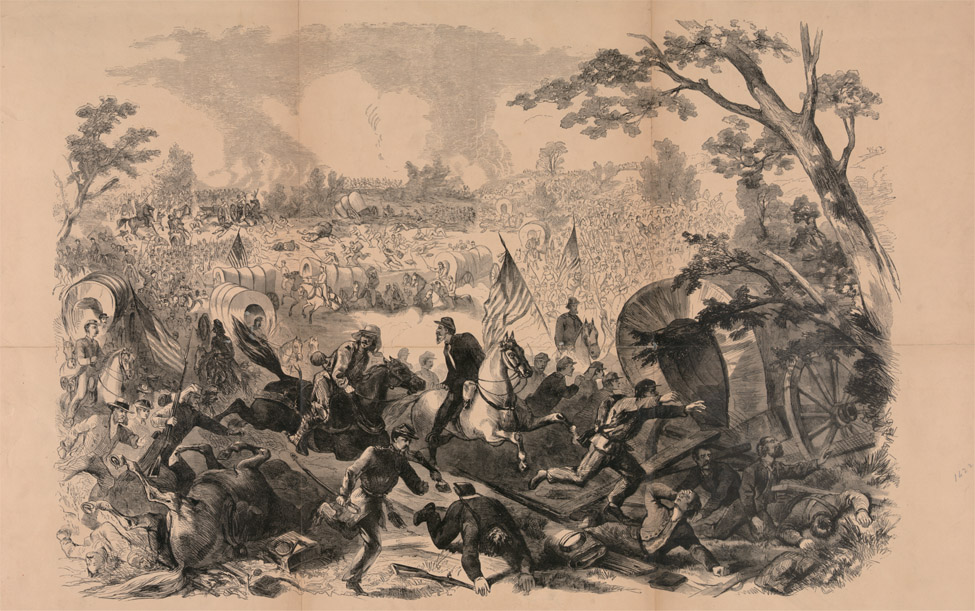

Several small battles won by the Confederacy in the summer of 1861 seemed to indicate that the South was en route to an early victory, and both armies readied for what each thought would be a single, gigantic, and ultimately decisive battle. On July 21 these armies—28,452 Union troops facing 32,232 Confederates—met at Bull Run Creek, Virginia, in a daylong clash that ended with the whipped Union Army running in sheer panic from the field back to Washington. The First Manassas, as Southerners referred to the battle, was both a resounding major victory for the Confederacy and a signal that this was to be a long, bloody war, just as Scott, who was active only in the earliest stages of the war, had predicted.

The Battle of First Bull Run, also known as First Manassas

After getting over the shock of initial Confederate victories and the threat against Washington itself, Union Army planners settled down and devised a multiphase strategy to use against the Confederacy, ironically based on Scott’s original ideas. One of the first offensive operations would be against North Carolina’s eastern coast to seize the vital ports and cut the north-south supply lines from Virginia. To start carrying out these plans, Major General Benjamin Franklin Butler and Commodore Silas Horton Stringham were given the task of attacking and capturing the most important Outer Banks access to mainland ports, Hatteras Inlet.

When the war began, one of the Union strategies was to blockade the entire Southern coastline to prevent supplies from coming in and amphibious forces from going out. To counter the threat on the Outer Banks, Confederate authorities had given their blessing to a quasi-military fleet of small sailing vessels, dubbed the “mosquito fleet” by the Southerners and “privateers” or outright “pirates” by the Union, that ran supplies through the blockade, helped defend the coastline, and raided Union ships when the opportunity arose. To back up these small ships, five strong forts and associated batteries were constructed all along the narrow coastal islands and placed under the overall command of Brigadier General Walter Gwynn and Brigadier (later Major) General Theophilus Hunter Holmes.

To defend the vital access to the mainland ports, North Carolina had constructed two forts on either side of the small village on the north bank of Hatteras Inlet: Fort Hatteras, mounting 12 32-pounder guns, was on the west side and closer to the channel itself, while Fort Clark, mounting 5 32-pounders, was a smaller post closer to the ocean. Commanding the Hatteras Island Garrison was Colonel William F. Martin, with about 400 men and 35 artillery pieces. With news of the approach of Union naval forces, Martin requested and received somewhere between 200 and 400 reinforcements (accounts vary significantly on this point).

Modern Times at Forts Hatteras and Clark

Due to wind, tide, and time, nothing remains of either post, save a marker near the ferry station indicating where the two forts were, now a spot in the Atlantic Ocean. A small museum at the base of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse houses a display about the Civil War activities here.

Despite the dearth of actual Civil War sites in this area, we recommend a visit as part of a tour of eastern North Carolina; while the Outer Banks have radically changed shape and size in the past 140-plus years, you can get a good idea of the terrain and weather that both sides had to endure in this campaign.

Sailing down from Fort Monroe, Virginia, was a Union naval force of seven ships under the direct command of Stringham mounting 143 cannon, accompanied by transports carrying Colonel Rush Christopher Hawkins’s 9th (Hawkins’s Zouaves) and Colonel Max Weber’s 20th (United Turner Rifles) New York Infantry Regiments and the 2nd U.S. Artillery Battery, under overall command of Butler. Arriving off the Outer Banks on the afternoon of August 27, Stringham spent the rest of the night getting his ships into position to begin a bombardment of the Confederate posts the next morning.

On the morning of August 28, Stringham opened a heavy bombardment of Fort Clark and landed roughly half of Weber’s regiment under its cover. Weber’s men easily overran the Confederate defenses after Fort Clark’s defenders ran out of ammunition and retreated to Fort Hatteras. Watching the Confederates running over the sand dunes toward the westernmost fort, Stringham initially thought both posts had been abandoned. The USS Monticello was ordered into the inlet to give chase, only to be pounded by heavy fire from the still-ready-and-able defenders at Fort Hatteras. Ironically, the only Union casualty of the day’s action was an infantryman killed by one of Stringham’s guns. As the seas were rough, Stringham was forced to pull offshore, leaving Weber’s small command to hold Fort Clark.

During the night, as Martin was preparing to attack and retake Fort Clark, Commodore Samuel Barron, chief of Confederate Coastal Defenses, landed with about 200 reinforcements and took over command of the operation. His first action was to cancel any offensive plans, and he spent the rest of the night repairing and building up the sand-work fort.

The next morning, August 29, Stringham sailed back into the inlet over calm seas and began a heavy bombardment of Fort Hatteras. Unusual for the time, he kept his ships moving while firing and stayed just out of range of the Confederate guns. After just three hours of intense fire, Barron was forced to surrender his post and troops.

After the fall of Forts Clark and Hatteras, Confederate authorities saw that defense of the narrow Outer Banks was going to require major manpower and resources, neither of which was in abundance. Fort Morgan at Ocracoke Inlet and Fort Oregon at Oregon Inlet were quickly evacuated and just as quickly taken over by Butler’s forces, leaving just Fort Fisher at the Cape Fear River inlet to guard the outer coast.

The only other action on this part of the Outer Banks was a bizarre set of pursuits between Hatteras and Chicamacomico (now called Rodanthe). On October 5, 1861, Hawkins had advanced toward the tiny north Hatteras Island town, aiming to capture and garrison it against the threat of a Confederate overland attack. As they closed in, six Confederate gunboats suddenly appeared, as well as part of a small Georgia infantry regiment (the 3rd Georgia Volunteers). A chase ensued, with the Union force running the 20 miles back to the safety of Fort Hatteras. The next morning, the chase began again, but this time Hawkins’s men pursued the Confederates all the way back to Chicamacomico. Both sides’ navies joined in on the fun, running on either side of the narrow banks in support of their troops. Besides a relative handful of casualties, absolutely nothing came out of what the locals referred to as the “Chicamacomico Races.”

With the quick fall of all Confederate defenses on the Outer Banks, two things became glaringly obvious: First, there would be a major effort by Union forces to capture the mainland ports, and second, the only thing standing in their way was the small garrison on Roanoke Island. As the defense of the entire area was now under Confederate control, Governor Clark, who had replaced Governor Ellis after his death, had little control over the buildup of a strong defense network, which the civilian population was demanding from him. Richmond responded to his appeals by simply stating that all available trained men were urgently needed in Virginia (not coincidentally, where the officials stating this were also located) and that only newly recruited units were available.

Brigadier General Richard Caswell Gatlin was placed in command of the newly formed Confederate Department of North Carolina. Brigadier (later Major) General Daniel Harvey Hill was initially given the responsibility of defending Albemarle and Pamlico Sounds (the body of water between the Outer Banks and the North Carolina mainland), and Brigadier General Joseph Reid Anderson took command of the District of Cape Fear, based out of Wilmington. Hill was apparently less than happy with his new command and soon resigned in order to return to General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. To replace him, Gatlin placed Brigadier General Henry Alexander Wise in charge of the area north of Roanoke Island and Brigadier General Lawrence O’Bryan Branch in charge of the stretch from Roanoke Island to New Bern.

Exact numbers are very hard to pin down, but Wise and Branch had somewhere around 8,000 men between their commands, most with Branch in New Bern. Roanoke Island itself was guarded by a few earthwork forts; on the east (seaward) side of the island was a tiny, unnamed two-gun redoubt at Ballast Point, and in the center was Fort Russell, a three-gun redoubt having a clear field of fire over the only road. On the northwest (landward) side of the island were three small sand-work forts, Forts Huger, Blanchard, and Bartow, mounting a total of 25 guns. No posts were established on the southern side of the island, possibly because the land was marshy and difficult to build on.

The most unusual defensive position was Fort Forrest, a partially sunken ship on the mainland side of the sound that had been reinforced and mounted with eight guns. The entire Confederate garrison numbered a mere 1,434 North Carolinians and Virginians, soon placed under direct command of Colonel H. M. Shaw, after Wise became too ill to lead the defense. Shaw was intensely disliked by his own men; one source quotes a soldier remarking that he was “not worth the powder and ball it would take to kill him.”

Sailing rapidly toward this unhappy situation was the largest amphibious force the United States had ever mounted to that time: 67 gunboats and troop transports under command of Commodore (later Rear Admiral) L. M. Goldsborough, carrying more than 13,000 soldiers under command of Brigadier (later Major) General Ambrose Everett Burnside, an undistinguished commander better known for his namesake whiskers than his military prowess. In his postwar memoirs, General in Chief Ulysses S. Grant said that Burnside was “an officer who was generally liked and respected. He was not, however, fitted to command an army.” By February 4, 1862, the fleet had crossed Hatteras Inlet safely and prepared to sail north into combat against Confederate forces.

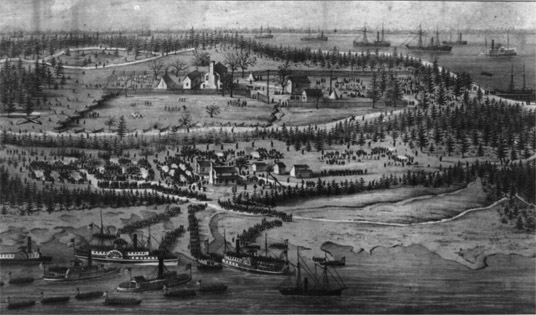

The Burnside Expedition landing at Roanoke Island, February 7, 1862

Burnside’s fleet moved north through Pamlico Sound and arrived just off Roanoke Island on February 7, opening fire on Fort Barrow between 10:30 and 11 a.m. Out of range, none of the Confederate batteries was able to return in kind the pounding artillery barrage. The Union Navy kept up their fire all day long, and as darkness approached, Burnside began landing his infantry at Ashby’s Harbor, about 3 miles south of the southernmost Confederate fortification. A scouting force of about 200 Confederates was nearby when the first Union troops came ashore, but the Southerners elected to retreat to Fort Russell without firing a shot. By midnight, more than 10,000 Union soldiers were ashore, along with several artillery batteries, and making preparations to move north at first light.

At dawn, three Massachusetts infantry regiments (the 23rd, 25th, and 27th) attacked Fort Russell, strung in a line formation across the road and into the swamps on both sides. The 400 Confederate defenders opened a heavy fire down the road, blocking the 25th Massachusetts advance, but they were soon forced to pull out when the other Union infantry appeared out of the swamps on both flanks. As the Massachusetts men entered the redoubt to take the abandoned guns, Hawkins’s Zouaves (the 9th New York Infantry Regiment) burst out of the woods and ran screaming over the redoubt’s walls. Hawkins claimed ever after that his men had bravely charged and taken the “heavily defended” post.

As the rest of the Union infantry regiments rapidly advanced north on the small island toward the remaining three forts, Shaw decided that any further action was futile and surrendered without firing another shot. In all, 23 Confederate soldiers, including Wise’s own son, were killed in the brief action, 58 were wounded, 62 missing, and about 2,500 captured, including nearly a thousand newly landed reinforcements from Nags Head. Burnside reported his losses at 37 killed, 214 wounded, and 13 missing, including 6 sailors killed and 17 wounded by return fire from Fort Bartow.

With the Outer Banks and Roanoke Island secured and available as staging bases, Burnside turned his attention to the mainland. His overall strategy from this point on seems a little less clear-cut than the assault on the Outer Banks; his postwar writings in Battles and Leaders only state that he had presented a rather vague plan to General of the Army George B. McClellan, to outfit an amphibious force “with a view to establishing lodgements on the Southern coast, landing troops, and penetrating into the interior …”

With the Confederate “mosquito fleet” fleeing with hardly a shot fired before the powerful Union naval task force, elements of Commandant Goldsborough’s fleet set off after their base at Elizabeth City, across Albemarle Sound from the newly captured island, taking it with little resistance on February 10. Part of Burnside’s infantry command joined the navy for “assaults” on other, nondefended towns off the sound; Edenton was ransacked on February 11, and Winton was burned to the ground on the 20th. Burnside and Goldsborough then turned their attention to the south, across Pamlico Sound toward New Bern and Morehead City.

To defend against the oncoming Union force, Branch had about 4,000 ill-trained and untested troops, stretched in a line from an old earthwork named Fort Thompson near the Neuse River, across the Atlantic and North Carolina Railroad track to Morehead City, and on nearly 2½ miles to the bank of the Trent River. Later Civil War doctrine called for a line this size to be held by at least 10 times this number of men. Six smaller earthwork redoubts surrounded the city, and an incomplete line of trench works and redoubts ran around the outside of Fort Thompson, all unmanned due to the manpower shortage. Branch’s only real defensive advantage was the 13 guns inside Fort Thompson and the 12 scattered down the line of battle. The other forts were mounted with cannon, but none was positioned to resist a land-based attack.

On March 12 the Union fleet arrived in the Neuse River about 14 miles south of New Bern, and that night Burnside gave his orders for the attack. The men were to land the next morning, march north along the Morehead City Road, and attack the Confederate line at the earliest opportunity.

Branch had arranged his men in an interesting fashion, possibly due to his total lack of experience or training as a military officer (he was a lawyer turned politician turned politically appointed general). From the fort to the railroad track, he placed four regiments, Major John A. Gilmer’s 27th, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas L. Lowe’s 28th, Colonel James Sinclair’s 35th, and Colonel Charles C. Lee’s 37th North Carolina Infantry, with Colonel Clark Avery’s 33rd North Carolina Infantry Regiment just behind them in reserve. To the right (west) of the railroad, he placed Colonel Zebulon B. Vance’s 26th and Colonel R. P. Campbell’s 7th North Carolina Infantry Regiments. In the middle, at the critical point in his line pierced by the railroad, he placed the least able of his men, the newly recruited, still un-uniformed and mostly shotgun-equipped Special Battalion, North Carolina Militia, led by Colonel H. J. B. Clark.

On the morning of March 13, Burnside’s troops waded ashore unopposed, the entire force able to join on land by 1 p.m. It had begun raining, and by the time the Union troops started moving north, the roads had become a quagmire of mud. Burnside said later it was “one of the most disagreeable and difficult marches that I witnessed during the war.” It took until dark to move north to the Confederate picket line, where it was decided to bivouac for the night and attack the next morning. Without tents or shelters of any kind, the night must have been a most difficult one for the rain-soaked infantrymen.

As dawn approached on the 14th, Burnside split his command into three brigades: Brigadier General John Gray Foster’s 1st Brigade was to attack on the right, Brigadier General John Grubb Parke’s 3rd Brigade the center, and Brigadier General Jesse Lee Reno’s 2nd Brigade was to roll up the extreme left. As dawn broke, the three Union brigades moved out.

Burnside had camped for the night much closer to the Confederate line than he had thought, and the lead brigade, Foster’s 1st, was in action almost immediately. Branch ordered the landward-facing guns of Fort Thompson to open up, which was answered by return fire from Union gunboats sailing in support up the Neuse River. Foster’s men were caught in the crossfire, suffering heavy casualties, and were soon forced to withdraw. Seeing the attack was bogging down on his right and spotting the break in the Confederate line at the railroad track, Reno led the four regiments under his command into the breach, the 21st Massachusetts Infantry in the front.

Map of the Battle of New Bern, March 14, 1862

With the Union infantry storming down the road toward their position, the militiamen broke and ran, most without firing a single shot. With the line to their right caving in, the 35th North Carolina soon followed suit. The only reserve regiment, the 33rd North Carolina, quickly moved up to plug the hole in the line and, between their volley fire and that of the 26th North Carolina to the right, soon broke up the Union attack and hurled it back. Reno moved further to his left and prepared to attack once again.

By this time, the third Union brigade, Parke’s, had moved into position, and all three brigades launched a renewed attack on the Confederate line at nearly the same time. This time the attack was successful, with Union infantry pouring through gaps in the line and raising their battle flags on the ramparts of the Confederate defenses. Branch, seeing his entire command caving in, ordered everyone to disengage and move back into New Bern. Once there, apparently believing Burnside was hot on his heels when in fact the Union assault had stopped for a rest within the breastworks, Branch ordered New Bern to be immediately evacuated and his headquarters moved to Kinston, 40 miles farther east.

When Burnside’s men moved into town on the afternoon of the 14th, all Confederate troops had fled, and the town was taken without further incident. Rather than trashing and burning the place, as was the Union custom, Burnside decided to garrison the town and use it as a supply and headquarters station for raids into the rest of North Carolina. Union troops held the town for the rest of the war. The short campaign had cost Burnside 90 killed and 380 wounded and another 4 sailors wounded, while Branch lost 64 killed, 101 wounded, and 413 captured or missing.

With New Bern newly secured, Burnside had only one task left to bring the entire central and eastern coasts under Union control—the seizure of Fort Macon on Bogue Banks, just across Bogue Sound from Beaufort just 33 miles to the southwest, guarding the only inlet left in Confederate control along the Outer Banks. With this post under Union control, the port of Morehead City would be open to Union troop and supply shipments to use in the planned invasion of central and southern North Carolina.

Fort Macon was named for Nathaniel Macon, who was Speaker of the House of Representatives and a U.S. senator from North Carolina. The five-sided structure was built of brick and stone with outer walls 4.5 feet thick with more than 9.3 million locally produced bricks, and it mounted 54 artillery pieces of various calibers. At the beginning of the war it was seized, in a scene repeated all over the coastal South, by local militia who demanded the post from the single ordnance sergeant who manned it.

At the time of Burnside’s expedition, Fort Macon was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel (later Colonel) Moses J. White of Vicksburg, Mississippi, with a garrison of about 450 (some accounts say 480 to 500) infantry and artillerymen.

With the Union Navy already under way to lay siege to the fort, Burnside ordered Parke to take his 3rd Brigade, with about 1,500 men fit for duty, south along the road through Morehead City and to lay siege to the Confederate outpost by land. Parke left New Bern on March 18 and walked into Morehead City without resistance five days later. After taking Beaufort the next day, also without resistance, Parke immediately and politely requested Fort Macon’s surrender; White, also politely, turned down his request. White knew that, without reinforcement or resupply, his post was doomed, but he was determined to fight it out as long as possible.

Over the next month the Union Navy landed men and supplies on Bogue Banks west of the fort and constructed a series of artillery redoubts and firing pits that gradually extended closer and closer to the fort. White’s men could only stand and watch and fire at the occasional ship or redoubt that came too close. By April 22 Parke had managed to emplace heavy cannon and siege mortars within 1,200 to 1,400 yards of the fort’s walls. Parke once again asked for surrender and was once again turned down.

The Union land batteries opened fire at dawn on April 25, and the Navy joined in a little after 8 a.m. White’s were high-velocity, flat-trajectory guns unable to hit the well-entrenched redoubts, but they raked the Union ships with a murderous fire, causing them to break off and retreat in less than one hour. Parke kept up an accurate and heavy fire for nearly 11 hours, helped in no small part by a Union signal officer in nearby Beaufort who watched the impact of each round and signaled corrections to the artillerymen. With his help, about 560 of the 1,100 rounds fired landed inside the fort, an amazingly high statistic for the time.

By 4 p.m. White had suffered enough and signaled that he was ready to ask Parke for a truce. The firing stopped immediately. The next morning, White went aboard the schooner USS Alice Price and surrendered his post and his command. By noon the 5th Rhode Island Infantry Regiment marched inside the fort’s walls and raised the Stars and Stripes once again. Losses on both sides were quite light for such a heavy bombardment; 7 Confederates were killed and another 18 wounded, while Parke suffered the loss of 1 dead and 3 wounded.

Beaufort served as a supply station for the Union Army and Navy for the rest of the war, despite several rather weak attempts to recapture it. With all eastern water accesses of the state now under Union control, Confederate authorities prudently pulled their overmatched forces back into the interior and north to support Lee’s army in Virginia. By springtime Union troops had marched in and taken Plymouth and Washington, North Carolina, without opposition.

With the exception of a continuous series of Union and Confederate raids that produced nothing for either side, no major offensive was launched in North Carolina for nearly three more years. The major battles had shifted away from the supply and farming region of eastern North Carolina to the heart of the Confederacy in Tennessee, Mississippi, and Georgia, and to the seemingly endless struggle around Richmond, Virginia.

After Burnside’s successful 1861–62 campaign in the eastern portion of the state had cut off Confederate supply and transport routes into Virginia, Wilmington inherited a vital role as the most important safe port for blockade-runners. The supplies they managed to sneak past the Union fleet were then transferred to trains on the Wilmington & Weldon Railroad and sent north to Lee’s army. Lee remarked on several occasions that he would not have been able to fight on so long without this steady flow of supplies. Two other railroads carried some supplies to the western portion of the state and then on to Tennessee and Georgia, and down to Charleston and Columbia in South Carolina.

Wilmington had a very favorable and easily defended location 26 miles inland on the wide and deep Cape Fear River, whose twin entrances from the Atlantic Ocean were well fortified. Also to the Union Navy’s grief, it was very nearly impossible to sail into the river inlet without the use of local, firmly Confederate guides to show the way through the treacherous Frying Pan Shoals.

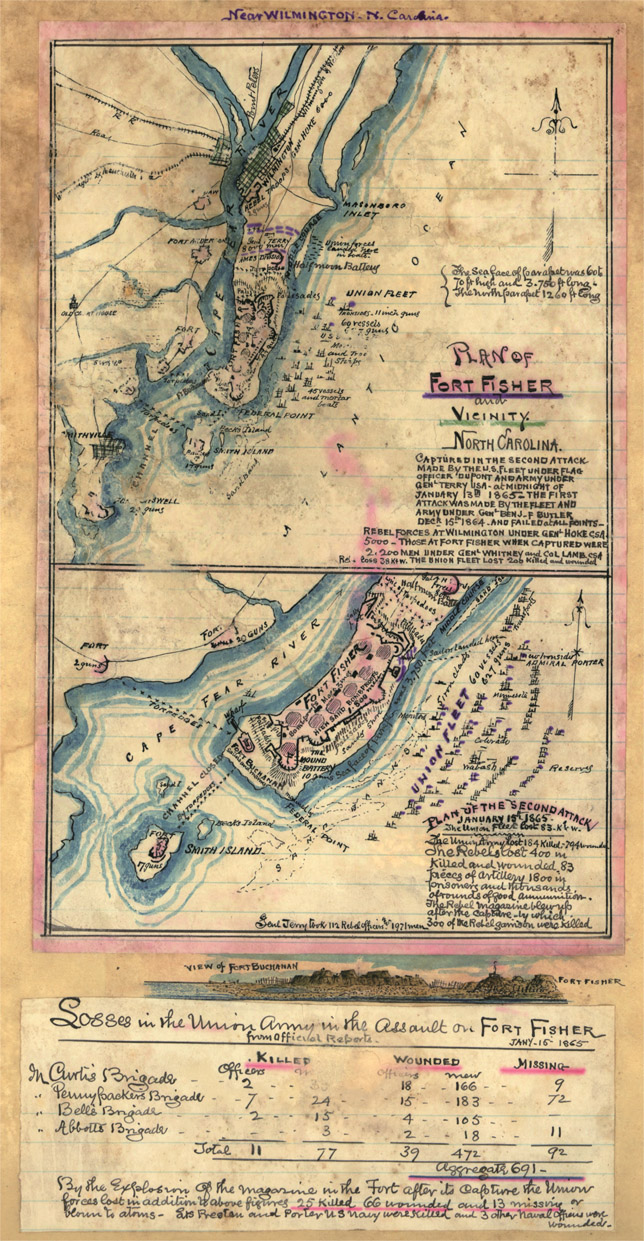

To guard against even the remote possibility of a Union attempt to assault the city by water, there were no less than six forts. The two channels into the Cape Fear River are separated by Smith’s Island (now called Bald Head Island), the location of Fort Holmes. On the west bank of the river above the island were Forts Johnston (later renamed Pender) and Anderson, while the lesser-used Old Inlet was guarded by Fort Caswell and Battery Campbell. To guard the much more heavily used New Inlet, a massive sand-work fortification called Fort Fisher was constructed on Federal Point starting in the summer of 1861. Fisher was not a fort in the classic sense, as it did not have encompassing walls. Instead, it was L-shaped, with the longest side facing the expected avenue of attack, the Atlantic Ocean. Several earthwork redoubts and batteries surrounded each fort, adding to an already impressive amount of available firepower.

The Union blockade fleet had initially considered Wilmington an insignificant port, ignoring it at first and then placing only a single ship, the USS Daylight, off the coast in July 1861. By late 1864 its importance was clear even to Union planners in Washington; by that time more than 50 blockade ships lay just offshore. Even with this tight noose around the supply lanes, blockade-runners managed to slip through up until the time of the battle itself.

Fort Fisher

While Grant was tied up in the months-long battle around Petersburg, he realized that in order to bring the stalemated fight to a successful conclusion, he was going to have to cut Lee’s supply lines. Until the only remaining port supplying the Army of Northern Virginia, Wilmington, could be cut off or taken over, this was not going to be possible. Grant ordered General Benjamin Franklin Butler and Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter to take their forces south to capture the city. Butler had two divisions of infantry—Brigadier General Adelbert Ames’s 2nd of the XXIV Corps and Brigadier General Charles Jackson Paine’s 3rd of the XXV Corps—as well as two batteries of artillery, with a grand total of nearly 8,000 men. Porter commanded the largest force of ships ever assembled at that time in the United States under one command, nearly 60 ships mounting a total of 627 guns.

As attack on the port city was likely at some point, Confederate president Davis sent General Braxton Bragg to take over command of the defenses in December 1864. The previous area commander, Major General William Henry Chase Whiting, was a competent officer well liked by both his troops and the local citizens, and Davis’s choice of the notoriously inept Bragg to replace him (he was actually placed over Whiting, who stayed on to directly command the garrison) was loudly protested. The size of the command then around Wilmington is highly debatable, but it can be safely assumed that Bragg initially commanded somewhere around 3,000 men.

Lee was fully aware of the critical and vulnerable nature of the port city and warned Davis that, if the city fell, he would be forced to pull back and abandon Richmond itself. When the Virginia general learned of Butler and Porter’s advance down the coast, he sent Major General Robert Frederick Hoke’s division to help defend the vital port, adding another 6,000 men to the line.

Butler, considered by many on both sides to be Bragg’s equal in ineptness, was determined to open the Cape Fear River by reducing its strongest defense, Fort Fisher. On December 20, 1864, the Union fleet began arriving off the Wilmington coast in the midst of a severe storm, taking nearly three days to get organized. Finally, on the night of December 23, with nearly all his command present and ready to assault, Butler sprang his “secret weapon” on the unsuspecting Confederates.

Butler had decided that a ship loaded to the gills with gunpowder, floated to the outer defenses of Fort Fisher and then exploded, would reduce at least one wall of the sand-work post to dust and allow his troops to pour in through the opening. Amazingly, he managed to sell Porter on the idea and got Grant’s grudging approval to go ahead. (Butler and Grant were mortal enemies, and the supreme Union commander had simply wanted to fire Butler rather than allow him another chance to screw up, but could not due to Butler’s political connections.)

At 1:45 a.m. on December 24, an unnamed “powder ship” loaded with 215 tons of gunpowder was sailed to within 200 yards of the fort and then exploded. The resulting massive blast failed to even superficially damage the well-constructed fort, and the sleepy defenders peered out, wondering if one of the Union ships had just suffered a boiler explosion or something of a similarly innocuous nature. Despite the failure of his secret weapon, Butler ordered the planned attack to proceed.

As dawn crept over the horizon, Porter’s gunboats began a heavy bombardment of the fort, while Butler ordered his troops ashore to the peninsula just north of the Confederate stronghold. Capturing two small batteries and pushing back Confederate skirmishers, the Union troops had made it to within 75 yards of the fort by the morning of Christmas Day. Butler learned that General Hoke’s division was then only 5 miles away and moving in fast. Panicking, Butler ordered his troops to break off and return to the troop transports, which he in turn ordered to hoist anchor and sail away so fast that more than 600 infantrymen were left stranded on the beach. Porter, who had no idea what Butler was up to, was forced to send his own ships and sailors to the beachhead under fire from the defenders of Fort Fisher to rescue the stranded troops. Butler reported a loss of 15 wounded and 1 killed in action (by drowning), while the Confederates suffered about 300 killed, wounded, and captured, as well as the loss of four precious artillery pieces.

A furious Grant immediately fired Butler, damning the political consequences, and hurriedly assembled another, stronger assault force under Major General Alfred Howe Terry. He sent Porter a message: “Hold on, if you please, a few days longer, and I’ll send you more troops, with a different general.” Porter pulled about 25 miles offshore, to the general line of the Union blockade fleet, to await Terry’s arrival.

Porter did not have long to wait. Terry left Bermuda Landing, Virginia, on January 4, 1865, with a total of 8,000 soldiers. Joining Porter’s squadron just off Beaufort, the force sailed once again for the Cape Fear River, again through a strong storm, arriving late on the afternoon of January 12.

Whiting had received word that the Union force was en route to try again and, fearing that this attempt would be much stronger, personally led 600 North Carolina troops from the garrison at Wilmington to reinforce Colonel William Lamb’s garrison of 1,200. Hoke’s newly arrived command deployed on the peninsula north of the fort, in case the second assault followed Butler’s attempted route.

A few hours after the Union fleet arrived, Porter ordered all guns to open fire on the Confederate fort while the infantry landed north of Hoke’s line. Terry spent the next two days carefully bringing his total force ashore and deploying them in a semicircle around the fort. One Union brigade under Colonel Newton Martin Curtis was sent to the western end of the peninsula, capturing a small redoubt and digging in close to the fort.

At dawn on January 15, Porter’s ships once again opened up a massive bombardment, lasting more than five hours, until Terry signaled his men to advance. Riflemen from the 13th Indiana Infantry Regiment led the assault, dashing forward under fire to dig in less than 200 yards from the fort and then rake the parapets with a deadly accurate fire.

While this rifle fire kept the Confederate defenders’ heads down, Terry ordered forward Curtis’s brigade, now reinforced with Colonel Galusha Pennypacker’s brigade, against the western face of the fort. As the Union troops cut through the wooden palisades and dashed up the sand walls, Lamb’s men rose out of their shelters and met the Union soldiers with fixed bayonets and drawn swords.

As the western wall defenses broke down into a massive hand-to-hand melee, 2,200 sailors and marines from Porter’s command sprang forward to assault the northeastern corner of the fort. There, the Confederate defenders were able to return a disciplined fire, killing or wounding more than 300 of the naval command and forcing them to quickly retreat.

The Union’s Terry left the rest of his command before Hoke’s Confederate line, and Hoke never sent any of his men to help relieve the fort’s defenders at Bragg’s direct order. About 10 p.m., after hours of unrelenting and vicious hand-to-hand combat and the commitment of the last Union reserves, the seriously wounded Lamb finally surrendered his post. The exact numbers of dead and wounded Confederates are difficult to assess, as records of this fight are spotty and highly debatable as to accuracy, but somewhere between 500 and 700 were killed or wounded and another approximately 2,000 captured. The South’s Whiting himself was mortally wounded during the assault, dying less than two months later. Terry reported Union losses of 184 killed, 749 captured, and 22 missing, including the seriously wounded Curtis, who was shot three times while leading the way over the ramparts, while Porter reported the loss of 386 in addition to the casualties in his marine assault force.

Map of the Second Battle for Fort Fisher

As a morbid postscript to the hard-fought battle, on the morning of January 16 two drunk sailors (sometimes identified as U.S. Marines) were walking around, looking for something worth stealing, when they came to a heavy bunker door. Opening it, they lit a torch and stuck it in the dark opening. The resulting explosion of about 13,000 pounds of gunpowder killed 25 more Union soldiers, wounded another 66, and killed an unknown number of wounded Confederate prisoners in the next bunker.

With the main defense post now in Union hands, Bragg wasted little time mounting any sort of renewed defense. The next day Fort Caswell’s garrison was withdrawn and the walls blown up, followed in quick order by most of the rest of the forts, batteries, and redoubts. Fort Anderson was left manned to cover Bragg’s withdrawal. This post stayed until February 20, when Major General Jacob Dolson Cox’s XXIII Corps moved upriver and forced them out without much of a fight. The next day Hoke’s troops were finally withdrawn and escaped north with the last remnants of Bragg’s force to Goldsboro. On February 22, Mayor John Dawson of Wilmington rode out to surrender his city to the Union invaders.

As the campaign to take Wilmington wound to a close in February 1865, Confederate operations in the Deep South were rapidly coming together near the eastern North Carolina town of Goldsboro. Bragg’s defeated force was withdrawing there to regroup (and for its commander to figure out whom to blame for his latest disaster); Sherman was pounding through South Carolina, driving what was left of the Confederate Army of Tennessee and various attached militias before him toward Goldsboro; and the newly appointed U.S. Department of North Carolina commander, Major General John McAllister Schofield, had been directed to move in from New Bern and take Goldsboro under Union control.

Desperately seeking some way out of the disastrous conclusion now looming before him, Davis finally came to a long-overdue decision and appointed Robert E. Lee as general in chief of all of the combined Confederate armies. One of Lee’s first acts was to place General Joseph Eggleston Johnston once again as commander of the Army of Tennessee and almost incidentally as commander of the Confederate States of America (CSA) Department of the Carolinas, with an aggregate total of about 45,000 men of widely varying skill and training levels. Bragg was reduced to command of a division under Johnston, a move that no doubt humiliated him but delighted his many political enemies.

Johnston promptly ordered most of his command to concentrate with him in the central portion of the state, to make a stand against Sherman’s oncoming force. From reports filtering up from South Carolina, where Sherman was advancing without any real resistance, he knew that the Union commander was arrayed in a column four corps abreast in a nearly 60-mile-wide front. Johnston planned to concentrate his forces so as to hit Sherman from one flank and then attack each corps’s flank and defeat each in turn.

As Wilmington had been effectively, if hastily, abandoned by Bragg’s troops, Schofield found no wagons or trains there available to move his Union troops rapidly inland. Undeterred, he ordered his forces under Cox in the longer-held base at New Bern to also move inland, and by late February two great Union columns were heading west. Bragg had pulled some of his troops safely out of Wilmington and now had about 8,500 men under Hoke near Kinston to protect his headquarters at Goldsboro. Johnston had sent a few green troops under Hill to reinforce Hoke’s line, including a unit known as the “North Carolina Junior Reserves,” consisting mostly of completely untrained teenage boys.

On the morning of March 8, as Cox rather blandly moved up the Kinston Road toward Southwest Creek, Hoke and Hill moved out of the trench line in a well-timed attack and assaulted the Union column on both flanks. Several thousand surprised and horrified Union soldiers either ran or surrendered on the spot, while Cox hastily ordered the remainder to dig in and fight back. Sporadic fighting lasted the rest of the day and into the next, while some Union reinforcements came up to replace the scattered force. By nightfall on March 9, Cox had about 12,000 men in his trench line.

At dawn on March 10, Hoke swung around and hit the Union left flank while Hill struck the right flank, forcing a few troops to pull back or run, but both Confederate commands were forced to withdraw after a relatively short fight.

Seriously weakened by the three-day battle, Hoke and Hill were forced to withdraw back into Kinston and then almost immediately pull out as Cox’s stronger force approached. Cox entered the city on March 14, as Bragg pulled what was left of his forces back into Goldsboro.

Sherman had stormed through South Carolina without any real resistance and by the first of March was approaching Cherhaw, near the North Carolina border. After evacuating Charleston, also without a fight, Beauregard had directed Lieutenant General William Joseph Hardee to take his corps (with two divisions and 8,000 men) to Cherhaw and delay Sherman’s advance while everyone else got into some kind of order. Johnston determined that he should concentrate his forces near Fayetteville in order to best strike at Sherman’s flank, no matter if he went south toward Goldsboro or north toward Raleigh.

Schofield and Sherman agreed that they should link up their respective commands at Goldsboro before moving on Raleigh to cut the main Confederate supply line there; Johnston determined to strike hard at Sherman’s column and was maneuvering his forces to hit before that linkup could be accomplished.

Hardee wisely pulled his infantry steadily back from Sherman’s advance, leaving most of the fighting up to Major General Joseph Wheeler’s Cavalry Corps, who kept up a running battle with Sherman’s cavalry chief, Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick, most of the way to Fayetteville. Sherman’s infantry moved steadily forward, reaching Fayetteville on March 12. There he rested his troops for three days before starting out again.

As he had in Georgia and South Carolina, Sherman had arranged his force of four corps into two great columns covering a 60-mile front; on the left were the XIV and the XX Corps, collectively referred to as the Army of Georgia, under Major General Henry Warner Slocum. On the right were the XVII and XV Corps under one-armed Major General Oliver Otis Howard, collectively referred to as the Army of Tennessee. On March 15 the great Union Army marched out of Fayetteville northeast toward Goldsboro and an expected linkup with Schofield’s army.

Hardee had pulled back to a strong defensive position near the tiny settlement of Averasborough, on the Raleigh Road, atop a ridgeline between a swamp and the Cape Fear River. On the afternoon of March 15, not long after leaving Fayetteville, Kilpatrick’s Cavalry Corps, attached to Slocum’s Corps, ran into the line of Confederate defenses and immediately tried to ram their way through them. Hardee’s men held fast, forcing Kilpatrick to withdraw and request infantry support. Slocum deployed his men during the night and at dawn on March 16 assaulted Hardee’s line.

Hardee’s only task was to delay the Union force, and he did an outstanding job here. Alternately pulling back and counterattacking, Hardee’s fewer than 6,000 men forced Slocum to deploy his entire XX Corps and then order up the XIV Corps for reinforcements late in the afternoon. By nightfall, well over 25,000 Union soldiers were engaged or deployed for battle, while Sherman’s lines were starting to become unstrung, just as Johnston had hoped. Rather than turn and support Slocum’s fight, for some unknown reason, Howard’s right wing kept moving forward, separating the two armies by more than a day’s march by the morning of March 17.

As darkness fell, Hardee broke contact and moved his small force rapidly back toward Johnston’s line outside Goldsboro, no doubt pleased that his actions had delayed the Union left wing by at least two days. About 600 Union soldiers were killed or wounded, while Hardee reported a loss of about 450.

Unknown to Sherman and Slocum, Johnston was massing his available forces just 20 miles north, outside the tiny village of Bentonville and hidden in the woods on the north side of the Goldsboro Road. Howard’s right wing was advancing down the New Goldsboro Road about 4 miles to the southeast and was well down the road by the time Slocum got his troops reorganized and on the road again. Sherman was convinced that Johnston, the defensive genius, was entrenching around Raleigh at that very moment. With Hardee’s corps still advancing up the road from Averasborough, the Confederate commander could muster about 21,000 men, as opposed to the 30,000 in Slocum’s command alone.

As Brigadier General William Passmore Carlin’s 1st Division, the lead elements of Slocum’s XIV Corps, moved up the Goldsboro Road early on the morning of March 19, his skirmishers started engaging what they thought were local militia. Instead, they were running straight into Hoke’s newly reinforced command arrayed across the road, fresh up from the battles around Wilmington. Slocum ordered an envelopment movement to his left, which instead had his men running straight into the middle of Johnston’s main line of battle.

As the battle started unfolding, Major General Lafayette McLaw’s division, the vanguard of Hardee’s command, finally arrived. Johnston, responding to panicked requests for reinforcements from Bragg, sent the road-march-weary soldiers over to the far left of his lines to join Hoke, arriving only to see the Union troops retreating in disarray. Johnston’s tactical plan had been to stop and break up the Union column and then spring a strong attack into their flank from his wooded position as soon as possible. Thanks to Bragg’s continued ineptness as a battlefield commander, the chance to do this with McLaw’s troops was lost.

While the rest of Hardee’s command moved into position and Johnston prepared to attack, Slocum had his men hastily dig in and sent word for his XX Corps to move up as soon as possible. The Union commander also sent word to Sherman that he had found Johnston’s army and requested Howard’s army be moved north into the rapidly growing battle.

Just before 3 p.m., with all his forces now in place and ready, Johnston gave the order to start what became the last major Confederate offensive of the war. Led by Hardee, Johnston’s combined force swept out of the woods and thundered down on Carlin’s seriously outnumbered division. In minutes the Union line fell apart, and Johnston’s screaming men ran down the road toward the next Union division coming into the line, Brigadier General James Dada Morgan’s 2nd Division.

Morgan had ordered his men to quickly construct a log breastwork soon after encountering Hoke’s men, and this hastily built barricade broke up the Confederate assault. Under heavy fire, Hardee’s men hit the ground and returned fire, while Hoke was ordered out of his trench line into the assault. Soon, every reserve Johnston could muster was thrown into the fight, while Slocum’s XX Corps made it into the line in time to withstand the assault. As darkness fell, Johnston ordered his men to break contact and pull back to a strong defensive position near Mill Creek, while Sherman ordered Howard’s entire Army of Tennessee north into battle.

Very little fighting occurred during the day of March 20, with Johnston strengthening his position around Mill Creek and Howard’s two corps moving into the line of battle. As day dawned on March 21, both armies stood static in their defensive lines, with Johnston trying to keep his force intact and Sherman simply wondering when his Confederate opponent would withdraw and allow him to proceed to his rendezvous with Terry and Cox at Goldsboro.

By the middle of the afternoon, hot-headed Major General Joseph Anthony Mower grew impatient and ordered his division to advance, totally without orders from either Slocum or Sherman. Moving west along a narrow path along Mill Creek, Mower’s men blew past pickets set up in the rear of Johnston’s line and soon advanced to within 600 feet of Johnston’s headquarters. Commanding a hastily assembled counterattack, Hardee personally led a Texas cavalry unit into Mower’s left flank, followed in short order by cavalry and infantry attacks on every flank of the Union command. Mower was soon forced out of the Confederate lines with heavy losses, but his division managed to inflict the ultimate blow on Hardee. Private Willie Hardee, his son, was a member of the very Texas cavalry brigade the general led into battle and was mortally wounded in the heavy exchange of fire.

Johnston had had enough. During the night of March 21, he pulled the remnants of his command out of the line and headed back toward Raleigh. The ill-conceived stance had cost him 2,606 men killed, wounded, captured, or missing, while Sherman’s forces suffered a loss of 1,646. The only objective Johnston managed was the delay of Sherman’s march for a few days, while nearly destroying his own army in the attempt. With hindsight, it is clear that even if Johnston had managed the unlikely result of totally destroying Slocum’s Army of Georgia, he would have still faced the 30,000-plus-strong Army of Tennessee shortly thereafter.

Johnston had once commanded a powerful, relatively well-equipped, and extremely well-trained Army of Tennessee, 42,000 strong, before Sherman’s grinding “total war” tactics had reduced it to a pitiful shell of its former glory. “High” Private Sam Watkins, of the Maury Grays, 1st Tennessee Infantry Regiment, had marched for the South as part of this great army since the very beginning. In his postwar memoirs he remarked that his regiment had once numbered 1,250 men, had received about 350 replacements, and had joined with other regiments throughout the war, bringing it to a grand total of about 3,200 men, but after the Battle of Bentonville, it was reduced to just 65 officers and men.

Sherman rather halfheartedly moved on to Goldsboro on March 23, where he met up with Terry’s and Cox’s commands newly arrived from the coast, then moved north to take the abandoned city of Raleigh. There he received word on April 16 that Johnston wanted to discuss surrender terms. The two generals met at Bennett Place between Durham and Hillsborough, where very generous terms were offered to the courtly Confederate general after two days of talks. Both generals had just learned of Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, which no doubt added some haste to their efforts to end the fighting.

Bennett Place, where generals Sherman and Johnson met

Grant traveled south to tell his old friend Sherman that these terms were not acceptable to the new administration in Washington and that he would have to insist the Confederates accept the same terms offered to and accepted by Lee on April 9. Jefferson Davis, newly arrived in Goldsboro in flight from the Union armies, rudely ordered Johnston, his political enemy, to break away from Sherman’s armies and join him in flight to the south. Johnston quietly ignored him and, as Davis continued his escape attempt southward, met again with Sherman to discuss the surrender. After agreeing to the new, harsher terms, Johnston surrendered his once-great army on April 26, 1865.

Reasoning with Hurricane Season

Since our first research trips into this area, no fewer than seven major hurricanes have either hit this area or passed close by. The resulting floods and damage to roads, buildings, and beaches meant that many businesses had to shut down to undergo repairs. Most reopened, but next year will undoubtedly play host to another major hurricane season. Weather experts say that hurricane seasons peak and ebb in relative strengths and numbers of major hurricanes and that the East and Gulf Coasts can expect high levels of both for the next eight years or so. It is strongly suggested that you call ahead just before your trip to make sure that the roads are passable and your hotel is open, and it pays to monitor weather conditions during the hurricane season (roughly June through November, peaking in late August and September).

Averasborough Battle Sites

The Battle of Averasborough was fought a few miles northeast of Fayetteville, just off I-95 between Fayetteville and the intersection with I-40 near Benson. Very little of the battlefield remains untouched, but the initial point of contact is well marked. Take exit 65 off I-95 onto NC 82, and go north toward Godwin. About 1.2 miles past the US 301 intersection is a large historic marker on the left in a curve on the road. This marks Hardee’s initial position, and the battle moved more or less northwest from this point about 2 miles.

About another half-mile north on NC 82 is Lebanon, one of a handful of period structures in the area, which was used as a Confederate hospital during the brief battle.

Bellair Plantation and Restoration

1100 Washington Post Rd.

New Bern, NC

(252) 637-3913

The last and largest brick plantation country house of the 18th century in North Carolina, the Bellair Plantation (circa 1734) is a majestic three-story brick building approached from NC 43 North by two long driveways, one lined by lavish old cedars. Georgian handcrafted woodwork greets visitors at the imposing eight-paneled door and continues through the main rooms. Original family furnishings are still in the house, probably because Bellair was specifically guarded from harm during the Civil War by order of Major General Ambrose Burnside of the North. The written order, dated March 20, 1862, still hangs on the wall at Bellair. The basement holds the cooking fireplaces with tools and ironworks of the period. Forty-five-minute tours are offered on weekdays by appointment. Group discounts offered.

Bentonville Battleground State Historic Site

5466 Harper House Rd.

Four Oaks, NC

(910) 594-0789

www.nchistoricsites.org/bentonvi

A small museum houses a few artifacts collected from the battlefield, and across the road is a set of reconstructed trenches. The museum has a set of maps that depict fairly well how the battle unfolded, and a short film presentation gives a good account of the fight here. A special high-tech battlefield map uses 3,500 small lights to illustrate the movement of soldiers in coordination with a recorded battle description. This museum reopened in August 1999, after its first renovation since 1965. This site hosts the popular Bentonville Reenactment every five years on the third weekend in Mar. The next reenactment will be on Mar 20 and 21, 2010. The reenactor Web site is: www.bentonville145.com.

Next door to the museum is the Harper House, used as a Confederate hospital and partly restored to its wartime condition. It is kept locked, but the site manager will open it up for a tour on request. For those into the occult, we should mention that we have heard quite a few ghost stories about this house from the reenactor community; quite frankly, the image we have of what this place must have looked like as a wartime hospital, filled with amputees and other seriously wounded soldiers, is eerie enough.

In the woods behind the trench line is a portion of surviving earthworks constructed by Slocum’s men; a small path leads back to them. The museum has both a free driving-tour map and a book for sale about the battle; either (or both) are recommended in order to travel down the country roads east of the museum to find the actual battle-site markers (this site is on the extreme western edge of the actual battlefield). Be aware that most of the battlefield is now private property and not open for walking. In fact, this battlefield has been named as one of the most endangered from development in the nation.

Admission is free, but donations are accepted (and encouraged).

Bodie Island Lighthouse and Keeper’s Quarters

West of NC 12, between Nag’s Head and Oregon Inlet

Whalebone Junction, NC

(252) 441-5711

www.nps.gov/caha

This black-and-white beacon with horizontal bands is one of four lighthouses still standing along the Outer Banks. It sits more than a half-mile from the sea, in a field of green grass. The site is a perfect place to picnic.

In 1870 the federal government bought 15 acres of land for $150 on which to build the lighthouse and keeper’s quarters. When the project was finished two years later, Bodie Island Lighthouse was very close to the inlet, stood 150 feet tall, and was the only lighthouse between Cape Henry, Virginia, and Cape Hatteras. But the inlet is migrating away from the beacon, and the current lighthouse is the third one to stand near Oregon Inlet since the inlet opened during an 1846 hurricane. The first light developed cracks and had to be removed. Confederate soldiers destroyed the second tower to frustrate Union shipping efforts.

Wanchese resident John Gaskill served as the last civilian lightkeeper of Bodie Island Lighthouse. As late as 1940, he said, the tower was the only structure between Oregon Inlet and Jockey’s Ridge. Gaskill helped his father strain kerosene before pouring it into the light. The kerosene prevented particles from clogging the vaporizer that kept the beacon burning.

Today the lighthouse grounds and keeper’s quarters offer a welcome respite during long drives to Hatteras Island. Wide expanses of marshland behind the tower offer enjoyable walks through cattails, yaupon, and wax myrtle. You can stick to the short path and overlooks if you prefer to keep your shoes dry.

The National Park Service added new exhibits to the Bodie Island keeper’s quarters in 1995. The visitor center there is open daily. The lighthouse itself is not open, but you can look up the tall tower from below when National Park Service employees are present to open the structure. Even a quick drive around the grounds to see the exterior is worth it.

Brunswick Town State Historic Site/Fort Anderson

8884 St. Phillips Rd. Southeast

Winnabow, NC

(off NC 133, Southport, NC)

(910) 371-6613

www.nchistoricsites.org/brunswic/brunswic.htm

At this site stood the first successful permanent European settlement between Charleston and New Bern. It was founded in 1726 by Roger and Maurice Moore (who recognized an unprecedented real estate opportunity in the wake of the Tuscarora War, 1711–13), and the site served as a port and political center. Russelborough, home of two royal governors, once stood nearby. In 1748 the settlement was attacked by Spanish privateers, who were soundly defeated in a surprise counterattack by the Brunswick settlers. A painting of Christ presented to the People (Ecce Homo), reputedly 400 years old, was among the Spanish ship’s plunder and now hangs in St. James Episcopal Church in Wilmington. At Brunswick Town in 1765, one of the first instances of armed resistance to the British Crown occurred in response to the Stamp Act. In time, the upstart upriver port of Wilmington superseded Brunswick. In 1776 the British burned Brunswick, and in 1862 Fort Anderson was built there to help defend Port Wilmington. Until recently, occasional church services were still held in the ruins of St. Philip’s Church. The other low-lying ruins and Fort Anderson’s earthworks may not be visually impressive, but the stories told about them by volunteers dressed in period garb are interesting, as is the museum.

Admission to the historic site is free. Closed Sun and Mon. From Wilmington, take NC 133 about 18 miles to Plantation Road. Signs will direct you to the site (exit left), which lies close to Orton Plantation Gardens.

Cape Fear Museum

814 Market St.

Wilmington, NC

(910) 798-4350

www.capefearmuseum.com

For an overview of the cultural and natural histories of the Cape Fear region from prehistory to the present, the Cape Fear Museum, established in 1898, stands unsurpassed. A miniature re-creation of the second battle of Fort Fisher and a remarkable scale model of the Wilmington waterfront, circa 1863, are of special interest. The Michael Jordan Discovery Gallery, including a popular display case housing many of the basketball star’s personal items, is an interactive natural history exhibit for the entire family. The Discovery Gallery includes a crawl-through beaver lodge, Pleistocene-era fossils, and an entertaining Venus flytrap model you can feed with stuffed “bugs.” Children’s activities, videos, special events, and acclaimed touring exhibits contribute to making the Cape Fear Museum not only one of the primary repositories of local history, but also a place where learning is fun.

Museum hours vary by season; wheelchair accessible.

Cape Hatteras Lighthouse

1401 National Park Dr.

Manteo, NC

(252) 473-2111

www.nps.gov/caha

The nation’s tallest brick lighthouse, this black-and-white-striped beacon is open for free tours from early spring through the fall and is well worth the climb. It contains 268 spiraling stairs and an 800,000-candlepower electric light that rotates every 7.5 seconds. Its bright beacon can be seen more than 20 miles out to sea.

The original Cape Hatteras Lighthouse was built in 1803 to guard the area known as the “Graveyard of the Atlantic,” but it was poorly designed with an underpowered light. One sea captain dubbed it the “worst light in the world.” Standing 90 feet tall and sitting about 300 yards south of its current site, the first lighthouse at Cape Hatteras was fueled with whale oil, which didn’t burn bright enough to illuminate the dark shoals surrounding it. This was an invitation to disaster, as just off this eastern edge of the Outer Banks, the warm Gulf Stream meets the cold Labrador Current, creating dangerous undercurrents around the ever-shifting offshore shoals. Erosion weakened the structure over the years. Finally, in 1861 retreating Confederate soldiers took the light’s lens with them, denying the Union Navy the light’s harboring safety but also leaving Hatteras Island in the dark.

The lighthouse that’s still standing was erected in 1870 on a floating foundation and cost $150,000 to build. More than 1.25 million Philadelphia baked bricks are included in the 180-foot-tall tower. A special Fresnel lens that refracts the light increases its visibility.

During the summer of 1999, the National Park Service moved the lighthouse 1,500 feet inland, at a cost to the federal government of $12 million. This move was in the nick of time, as multiple hurricanes shortly thereafter seriously eroded the coastline near the old location.

Staffed entirely by volunteers, the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse is open all the way to the outdoor tower at the top. The breathtaking view is like looking off the roof of a 20-story building. And the free adventure is well worth the effort. The climb is strenuous, so don’t attempt to carry children in your arms or in kid carriers. Climbing is permitted from mid-Apr through Columbus Day. The visitor center, museum, and grounds are open year-round. Tickets to the lighthouse tour are sold on a first-come, first-served basis, and tours begin every 10 minutes, with a limit of 30 persons per tour. Children under 12 must be accompanied by an adult. Hours are subject to change, so call first. Nearby structures originally housing the lightkeepers and their families now house a fascinating museum of the history of both the lighthouse and Cape Hatteras itself.

Carteret County Historical Society/The History Place

1008 Arendell St.

Morehead City, NC

(252) 247-7533

www.thehistoryplace.org

In 1985 the Carteret County Historical Society was given the old Camp Glenn School building, circa 1907, which had served the community first as a school and later as a church, a flea market, and a print shop. The society moved the building from its earlier location to Wallace Drive, facing the parking lots of Carteret Community College and the Crystal Coast Civic Center, just off Arendell Street in Morehead City. The members renovated the building and created a museum to show visitors and residents how life used to be in Carteret County.

There are rotating exhibits with emphasis on the area’s Native American heritage, schools, businesses, and homes. The museum houses the society’s research library, including an impressive Civil War collection, that is available to those interested in genealogy and history. The museum conducts occasional genealogy workshops. Monthly exhibits feature area artists, and there is a gift shop. Admission is free.

Cedar Grove Cemetery

Queen St. and National Ave.

New Bern, NC

If you’re one of those people who loves wandering through old graveyards, you’ll not want to miss this one. Statuary and monuments beneath Spanish moss–draped trees mark burial traditions from the earliest days of our nation. One smallish obelisk lists the names of nine children in one family who all died within a two-year time span. The city’s monument to its Confederate dead and the graves of 70 soldiers are also here. The cemetery’s main gate features a shell motif, with an accompanying legend that says if water drips on you as you enter, you will be the next to arrive by hearse.

Dixon-Stevenson House

609 Pollock St.

New Bern, NC

(252) 514-4900

(800) 767-1560

www.tryonpalace.org/dixonhouse.html

Erected in 1828 on a lot that was originally a part of Tryon Palace’s garden, the Dixon-Stevenson House epitomizes New Bern’s lifestyle in the first half of the 19th century, when the town was a prosperous port and one of the state’s largest cities.

The house, built for a New Bern mayor, is a fine example of neoclassic architecture. Its furnishings, reflecting the Federal period, reveal the changing tastes of early America. At the rear of the house is a garden with seasonal flowers, all in white. When Union troops occupied New Bern during the Civil War, the house was converted to a regimental hospital.

First Baptist Church

411 Market St.

Wilmington, NC

(910) 763-2471

www.fbcwilmington.org

This is Wilmington’s tallest church. The congregation dates to 1808, and construction of the redbrick building began in 1859. The church was not completed until 1870 because of the Civil War, when Confederate and Union forces in turn used the higher steeple as a lookout. Its architecture is Early English Gothic Revival with hints of Richardson Romanesque in its varicolored materials and its horizontal mass relieved by the verticality of the spires, with their narrow, gabled vents. Inside, the pews, galleries, and ceiling vents are of native heart pine. Being the first Baptist church in the region, this is the mother church of many other Baptist churches in Wilmington. The church offices occupy an equally interesting building next door, the Conoley House (1859), which exhibits such classic Italianate elements as frieze vents and brackets and fluted wooden columns.

First Presbyterian Church

400 New St.

New Bern, NC

(252) 637-3270

www.firstpresnewbern.org

The oldest continually used church building in New Bern, First Presbyterian was built in 1819–22 by local architect and builder Uriah Sandy. The congregation was established in 1817. The Federal-style church is similar to many built around the same time in New England but is unusual in North Carolina. Like that of nearby Christ Episcopal Church, the steeple on First Presbyterian is a point of reference on the skyline. The church was used as a Union hospital and lookout post during the Civil War, and the initials of soldiers on duty in the belfry can still be seen carved in the walls. Visitors are welcome to tour the church between 9 a.m. and 2 p.m. weekdays.

Fort Caswell

100 Caswell Beach Rd.

Oak Island, NC

(910) 278-9501

www.fortcaswell.com

Considered one of the strongest forts of its time, Fort Caswell originally encompassed some 2,800 acres at the east end of Oak Island. Completed in 1838, the compound consisted of earthen ramparts enclosing a roughly pentagonal brick-and-masonry fort and the citadel. Caswell proved to be so effective a deterrent during the Civil War that it saw little action. Supply lines were cut after Fort Fisher fell to Union forces in January 1865, so before abandoning the fort, the Caswell garrison detonated the powder magazine, heavily damaging the citadel and surrounding earthworks. What remains of the citadel is essentially unaltered and is maintained by the Baptist Assembly of North Carolina, which owns the property. A more expansive system of batteries and a seawall were constructed during the war-wary years from 1885 to 1902. Fort Caswell is open for self-guided visits. Drive-throughs of the property are free. The fort is closed to tours from Memorial Day to Labor Day.

Fort Fisher State Historic Site

1610 Fort Fisher Blvd. S.

(off US 421, south of Kure Beach, NC)

(910) 458-5538

www.nchistoricsites.org/fisher

Fort Fisher was the last Confederate stronghold to fall to Union forces during the War between the States. It was the linchpin of the Confederate Army’s Cape Fear Defense System, which included Forts Caswell, Anderson, and Johnson and a series of batteries. Largely due to the tenacity of its defenders, the port of Wilmington was never entirely sealed by the Union blockade until January 1865. The Union bombardment of Fort Fisher was the heaviest naval demonstration in history up to that time.

Today all that remains are the earthworks, the largest in the South. The rest of the fort has been claimed by the ocean. However, a fine museum, uniformed demonstrations, and reenactments make Fort Fisher well worth a visit. Don’t miss the Fort Fisher Aquarium. Thirty-minute guided tours allow you to walk the earthworks, and slide programs take place every half-hour. The Cove, a tree-shaded picnic area across the road, overlooks the ocean and makes an excellent place to relax or walk. However, swimming here is discouraged due to dangerous currents and underwater hazards.

Since Fort Fisher is an archaeological site, metal detectors are prohibited. Museum hours vary by season. Admission is free (donations are requested). The site, about 19 miles south of Wilmington, was once commonly known as Federal Point. The ferry from Southport is an excellent and time-saving way to get there from Brunswick County.

Fort Johnston

Davis and Bay Sts.

Southport, NC

(910) 457-7927

The first working military installation in the state and reputedly the world’s smallest, Fort Johnson was commissioned in 1754 to command the mouth of the Cape Fear River. A bevy of tradespeople, fishermen, and river pilots soon followed, and so the town of Smithville was born (renamed Southport in 1887). During the Civil War, Confederate forces added Fort Johnson to their Cape Fear Defense System, which included Forts Caswell, Anderson, and Fisher. Fort Johnson’s fortifications no longer stand, but the site is redolent with memories of those times. The remaining original structures house personnel assigned to the Sunny Point Military Ocean Terminal, an ordnance depot a few miles north.

Fort Macon State Park

2300 E. Fort Macon Rd. (NC 58)

Atlantic Beach, NC

(252) 726-3775

www.ncparks.gov/Visit/parks/foma/main.php

Fort Macon State Park, at Milepost 0 on the east end of Bogue Banks, is North Carolina’s most visited state park, and with around 1.4 million visitors each year, it is the Crystal Coast’s most visited attraction. Initially the fort served to protect the channel and Beaufort Harbor against attacks from the sea. Today the danger of naval attack is remote, but during the 18th and 19th centuries this region was very vulnerable. The need for defense was clearly illustrated in 1747, when Spanish raiders captured Beaufort, and again in 1782, when the British took over the port town.

Construction of Fort Dobbs, named for Governor Arthur Dobbs, began here in 1756 but was never completed. In 1808–09 Fort Hampton, a small masonry fort, was built to guard the inlet. The fort was abandoned shortly after the War of 1812 and by 1825 had been swept into the inlet.

The fort was deactivated after 1877 and then regarrisoned by state troops in 1898 for the Spanish-American War. It was abandoned again in 1903, was not used in World War I, and was offered for sale in 1923. An Act of Congress in 1924 gave the fort and the surrounding land to the state of North Carolina to be used as a public park. The park, which is more than 400 acres, opened in 1936 and was North Carolina’s first functioning state park.

At the outbreak of World War II, the army leased the park from the state and, once again, manned the fort to protect a number of important nearby facilities. In 1944 the fort was returned to the state, and the park reopened the following year.

Today Fort Macon State Park offers the best of two worlds: beautiful, easily accessible beaches for recreation and a historic fort for exploration. Visitors enjoy the sandy beaches, a seaside bathhouse and restrooms, a refreshment stand, designated fishing and swimming areas, and picnic facilities with outdoor grills. A short nature trail winds through dense shrubs and over low sand dunes. The park is abundant with wildlife, including herons, egrets, warblers, sparrows, and other animals.

The fort itself is a wonderful place to explore with a self-guided tour map or with a tour guide. A museum and bookstore offer exhibits to acquaint you with the fort and its history. The fort and museum are open daily year-round. Fort tours are guided through late fall. Reenactments of fort activities are scheduled periodically from spring to fall. Talks on the Civil War and natural history and a variety of nature walks are conducted year-round.

Frisco Native American Museum

NC 12

Frisco, NC

(252) 995-4440

www.nativeamericanmuseum.org

This fascinating museum on the sound side of NC 12 in Frisco is stocked with unusual collections of Native American artifacts gathered over the past 65 years, plus numerous other fascinating collections unrelated to native peoples. Opened by Carl and Joyce Bornfriend, the museum boasts one of the most significant collections of artifacts from the Chiricahua people and has displays of the work of other Native American tribes from across the country, ranging from the days of early man to modern time. Hopi drums, pottery, kachinas, weapons, and jewelry abound in homemade display cases with hand-lettered placards.

Many visitors are astonished at the variety, amount, and eclectic appeal of the displays in the museum. The Friends of the Museum group has a small shop located beyond the museum book room that is called Collector’s Corner. It is a separate section, clearly labeled as a benefit shop for the museum. It has lots of collectibles, including some military items, political memorabilia, and Wedgwood, and all proceeds go to the museum. Native craft items made by about 40 artisans from across the country are also available for sale.

The book section and natural history center have recently been expanded. With advance notice, the Bornfriends will give guided tours of their museum and lectures for school and youth groups. Call for prices. The museum property also includes outdoor nature trails through three acres of woods, with a screened-in pavilion, a large pond, and three bridges on the land. Museum hours vary by season.

The Monitor

Off Cape Hatteras, in the Atlantic Ocean

Launched January 30, 1862, the Monitor is one of the nation’s most famous military ships. Its watery grave is the first National Underwater Marine Sanctuary. Divers sanctioned by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration have spent years retrieving items from the ironclad boat, which rests upside down in 230 feet of water about 17 miles off Cape Hatteras.

The Monitor was owned by Union forces and was their counterpart to the Confederate ship Virginia during the Civil War. The Virginia was the world’s first ironclad warship, built from the hull of the Union frigate Merrimac, which Southern forces captured and refitted. On Mar 8, 1862, the pup tent– shaped steamer Virginia cruised out of Norfolk to challenge a blockade of six wooden ships. By day’s end, the Virginia had sunk two of those Union ships and damaged another.

Built by Swedish-American engineer John Ericsson and appropriately dubbed the “Cheesebox on a Raft” because of its unusual design, the Monitor was a low-slung ironclad that included a revolving turret to carry its main battery. This strange-looking ship arrived in Norfolk on March 9 and soon battled the Virginia to a draw. Retreating Confederates eventually destroyed the Virginia. The Monitor was ordered to proceed farther south.

The New Year’s Eve storm of 1862 caught the Union ironclad off Cape Hatteras, far out in the Atlantic. The Monitor sank completely, taking its crew with it. Its whereabouts were unknown until university researchers discovered the Monitor in 1973.