South Carolina: First to Fight

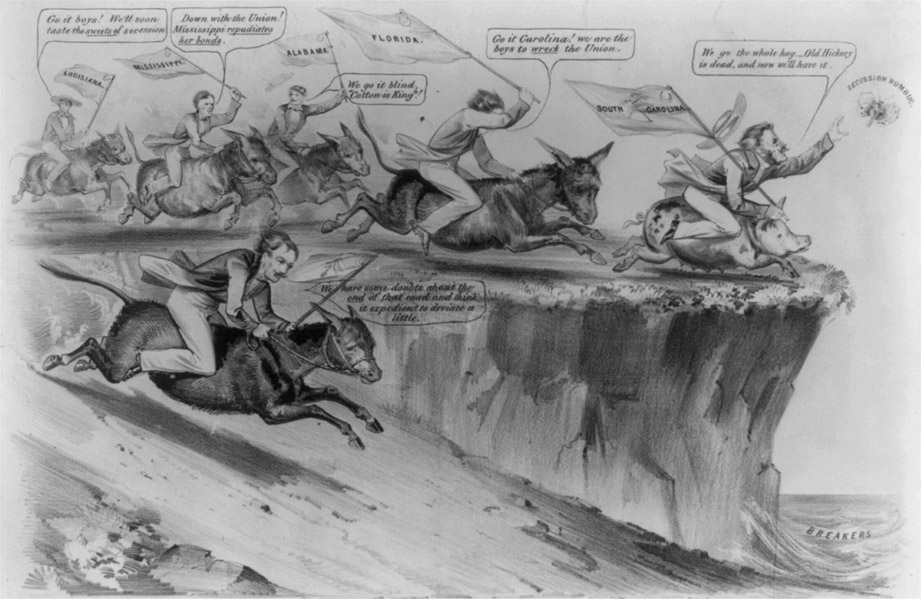

A contemporary cartoon shows one interpretation of the Secession Movement, with South Carolina in the lead.

For many people, the Civil War in South Carolina means one thing: Charleston. And in one sense they are quite correct. While South Carolina was the first to secede and one of the last to be brought under the Union Army’s control, only two relatively small battles were fought in the state outside the immediate Charleston area. In all, most of the combat in the state primarily revolved around the struggle for control of Charleston and the relatively weak resistance to Sherman’s 1864 march through the middle part of the state. Ironically, less fighting occurred in this most politically radical of the Confederate states than did in Florida, an oft-forgotten “backwater” theater of the war.

It can be (and is) endlessly debated whether the Civil War was fought over the issue of slavery, primarily or otherwise, but the fact is that this divisive issue was at least a motivation for the earliest efforts at secession. John Caldwell Calhoun of South Carolina, while a U.S. senator from 1832 to 1843 and again from 1845 to 1850, agitated constantly for “nullification,” the right of individual states to declare null and void and subsequently ignore any federal law, rule, or regulation that conflicted with their original agreement to join the Union. This was a widely popular stance in the South, whose slave-holding major landowners felt constantly threatened by abolitionist movements in the northern, “free” states.

The argument that “the Civil War was about freeing the slaves” doesn’t adequately explain what was going on politically in the United States before 1860. A thorough discussion of this would fill many volumes; for a well-researched and reasonable presentation, we suggest reading Battle Cry of Freedom by James McPherson. The first 300 pages give a good overview of this very complex time and introduce the major issues and personalities.

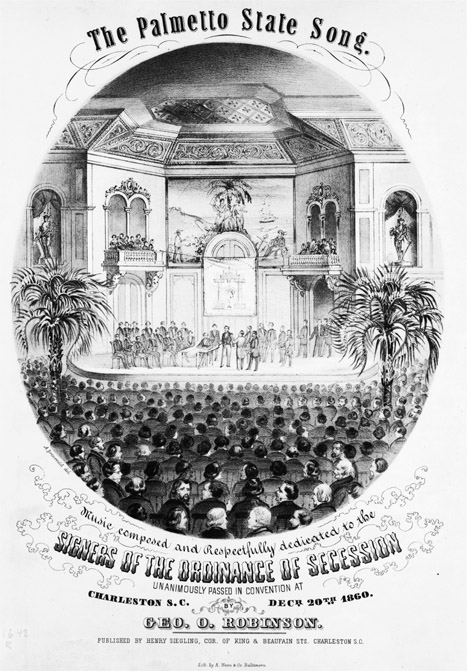

This sheet music cover celebrates the South Carolina state convention, held on December 20, 1860, where the state seceded from the Union. The cover illustration shows some of the 169 delegates who gathered to sign the secession documents.

In oversimplified terms, the South as a whole was obsessed with the idea that the 10th Amendment to the Constitution (among other documents) gives the individual states ultimate control over most acts of the federal government, and this control includes the right to declare itself separate from the Union if its citizens so desire. The North as a whole was equally obsessed with the idea that the federal government reigns supreme over acts of the individual states and that the Union as an entity was inviolate; once entered, it could not be exited without, at a minimum, the express consent of the federal government. This line of argument had been going on in one form or another since shortly after the United States became a sovereign nation, reaching an early peak in the federalist versus anti-federalist arguments of Alexander Hamilton and Patrick Henry.

Whatever the base cause, tensions were running so high by 1860 that the election of Abraham Lincoln was reason enough for South Carolina politicians to start calling for secession, literally within hours of the vote. A secession convention was called for in short order, meeting on December 18 and unanimously passing an Ordinance of Secession on December 20. The two-day delay in passing this measure was not due to any real opposition to the document but was necessary so that each of the 169 delegates could stand up in turn and bombastically grandstand about the “Yankee outrages.”

Minutes after the signing, the Charleston Mercury newspaper published a special edition proclaiming the new independence of South Carolina and expressing the hope that its Southern brethren would soon follow. The same thought occupied the Northern politicians, and Union military officials moved quickly to protect forts and installations around the Southern coastline.

Garrison commanders in Florida and South Carolina reacted swiftly to the War Department order (to protect their posts as best as possible, preferably without igniting a shooting war), gathering up their men in the strongest and easiest-to-defend of their forts and preparing for what could be a long siege. In Charleston, Major (later Major General) Robert Anderson abandoned the low-walled Fort Moultrie on Sullivan Island and moved his small Northern command to still-unfinished Fort Sumter, in the middle of the cold night of December 26. Before leaving, he “spiked” the guns of Fort Moultrie, rendering them unable to fire and useless, and burned most of the remaining supplies and equipment. As a final act of defiance, he ordered the post flagpole to be chopped down so that any of the assorted flags of secession would not fly from it.

Once inside Fort Sumter, Anderson was faced with a serious tactical situation; only 48 guns had been mounted in the 140 gun positions, and 27 of these guns were mounted en barbette atop the upper ramparts, where their crews would be exposed to hostile fire. In addition, he only had 84 officers and men to run the post and was responsible for housing and feeding another 43 civilian workers still attempting to complete construction of the fort. On the positive side, he had enough rations and supplies to last more than four months, even if he could not be resupplied.

The night after Anderson made his move, a group from the 1st Regiment of Rifles, one of the Charleston militias under Colonel (later Brigadier General) James Johnson Pettigrew, rowed out into Charleston Harbor and seized Castle Pinckney, one of the batteries that guarded Charleston Harbor. The only Union soldier present, Lieutenant Richard K. Meade, protested the invasion verbally and then got in his own rowboat and went off to Fort Sumter in a dark cloud over his “treatment” by Pettigrew. This was the first seizure of U.S. property by a seceded state and coldly indicated that this was not to be a happy separation. Meade tendered his resignation from the U.S. Army soon thereafter and joined the Confederate Army as an engineer. Pettigrew went on to greater glory in the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, leading a brigade under Major General Henry Heth and then taking over this division in charging Cemetery Ridge on the third day at Gettysburg (the so-called Pickett’s Charge). He was wounded in this disaster and again wounded 10 days later at the Battle of Falling Waters, that time mortally.

Through the rest of the winter of 1860–61, things were relatively quiet in Charleston. Confederate and Union forces alike worked to build up their defenses, the South Carolinians constructing, reinforcing, or rearming some 60 forts, batteries, and redoubts all around the harbor. Anderson worked on completing his post as best as possible with what workers and materials he had on hand—the U.S. government had entered into an uneasy agreement not to reinforce or resupply any of its besieged garrisoned forts in the South if they were in turn left unmolested.

Fort Sumter was a five-sided fort, 300 feet wide by 350 feet long, with walls about 40 feet high made of locally procured brick; it was built on an artificial island in the middle of Charleston Harbor. Construction began about 1828 on the main post to guard this major harbor. No natural land was sufficient upon which to build a strong fort upon in the harbor itself, so more than 70,000 tons of rock were dumped on a low sandbar to form a firm foundation. Construction progressed at a glacial pace; the post was still unfinished and most of the guns still unmounted when Anderson was forced to withdraw within its walls in December 1860.

Fort Sumter pictured with the Confederate flag still flying

As the first months of 1861 faded away, Anderson and his men worked to mount what guns they could and waited for their masters in Washington to figure out how to get them all out of this mess. While talks were going on, the USS Star of the West tried to slip into the harbor and resupply the garrison. As the Union supply ship sailed past the Confederate batteries on Morris Island on January 9, batteries manned by cadets from the nearby Citadel college opened fire. Moments later, two shots slammed into the ship’s wooden hull, prompting the captain to do an immediate about-face and head for safety. Some historians regard this as the true opening act of the military phase of the war.

Little happened for the next three months, until early April. Anderson’s garrison was running dangerously low on rations, the U.S. government seemed befuddled by the continued declarations of secession by the Southern states, seven in all by this time (in chronological order: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas). Newly appointed commander of Confederate forces in Charleston, Brigadier General (later full General) Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, knew that Anderson’s situation was growing critical and, with the full blessing of the new Confederate government, decided to take advantage of it. He also knew that a heavily armed U.S. Navy squadron was en route with supplies for the fort, prepared to blast its way in if necessary, and he would have to act quickly.

On April 11, 1861, Beauregard sent Anderson, his friend and old artillery instructor at West Point, a formal request for surrender of his post. Anderson replied politely, asking if he could wait until April 15 to surrender. Beauregard knew that the navy ships were due to arrive on the 14th and in turn refused. He further sent word to Anderson that he would fire on the fort if not surrendered by midnight. At 3:30 a.m. on Friday, April 12, Beauregard sent one last message to Anderson, stating that he intended to open fire in exactly one hour. Anderson then ordered his men down into the deepest and best-protected casements.

At 4:30 a.m., Captain George S. James yanked the lanyard of a 10-inch mortar mounted in Fort Johnson on James Island, sending an 88-pound shell arcing high over the dark harbor for 20 long seconds, which finally exploded with a bright flash and dull roar in the middle of the fort’s parade ground, a perfect shot. This was the signal for which every Confederate artilleryman around the harbor had been waiting for weeks. Within minutes, 30 guns and 17 heavy mortars opened fire as well, aiming at the darkened target only 1,800 to 2,100 yards away.

Anderson kept his men in the casements until dawn and then allowed them to man their guns, under strict orders not to man those on the upper, exposed parapets. Captain Abner Doubleday took the honor of yanking the lanyard to fire the first return shot. As each gun facing toward the Confederate-held fortifications came on line and began a disciplined return fire, Sergeant John Carmody snuck upstairs under heavy incoming fire and loaded up and fired a few of the barbette guns. As the fort had not been given a full load-out of ammunition before the secession crisis hit and had not been resupplied since, Anderson’s guns soon burned up what was left in the magazines. By late afternoon, only six smaller-caliber guns were able to keep up a steady fire.

Beauregard kept up a pounding fire for 34 straight hours, seriously damaging the fort’s three-story outer wall and raking the upper gun deck with hot shot and shrapnel. Noting that some of his hot-shot guns had set a few interior buildings ablaze, Beauregard ordered more guns to start firing the heated shells, quickly turning the fires into a massive blaze that threatened the otherwise-protected gun crews. Finally, after more than 4,000 well-aimed rounds had slammed into his post, Anderson signaled his surrender, at 1:30 p.m. on April 13.

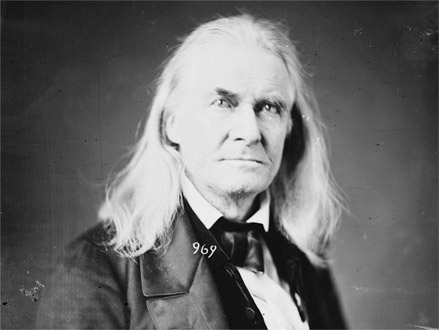

Confederate General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard

Confederate General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard

Two generations of Southern men are saddled with the middle name “Beauregard” in tribute to this immortal man; perhaps no other single Confederate officer so completely epitomized the aristocratic “gentleman officer.” Beauregard was born in St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana, on May 28, 1818, a true Creole who could speak French before English. He graduated second in his class at West Point in 1838, going on to help build the system of fortifications along the Gulf Coast and various command positions in and around New Orleans. During the Mexican-American War he served with a conspicuous flair, winning two promotions for gallantry as well as suffering two slight wounds. Immediately before the outbreak of hostilities, he was appointed superintendent of West Point but lost the post a few days later when he made it clear that he was not about to turn his back on a seceding Louisiana.

Upon resigning his U.S. Army commission in February 1861, he was almost immediately given a Confederate brigadier general’s commission and shortly placed in command of the Charleston defenses. There, on April 12, 1861, he directed the “opening shots” of the war against Fort Sumter, commanded then by Major Robert Anderson of the U.S. Army, Beauregard’s close friend and artillery instructor at West Point. His next command was over the Confederate forces in northern Virginia near Manassas Junction, where he commanded the main battle line in a great victory over superior Union forces on June 1. One of five brigadier generals subsequently promoted to full general (the others being Samuel Cooper, Albert Sydney Johnston, Robert E. Lee, and Joseph Eggleston Johnston), he was soon sent west after feuding with both President Jefferson Davis and his War Department.

At Shiloh, Beauregard served as second-in-command to A. S. Johnston, assuming command of the Confederate Army of the Mississippi upon Johnston’s death. A few months later, too ill to command, he turned over his command to General Braxton Bragg while he recovered, but Davis personally blocked his return to command later. He spent most of the rest of the war in command of the Carolinas and Georgia coastal defenses, briefly serving alongside Lee at Petersburg, and ended up serving under J. E. Johnston in his last stand in the Carolinas.

So great was Beauregard’s reputation here and abroad that he was offered command of both the Romanian and Egyptian armies, both of which he refused. He lived out the rest of his life in Louisiana, working in several administrative posts, and died in New Orleans on February 20, 1893.

It is almost beyond belief that not a single man on either side had been seriously wounded or killed in the day-and-a-half exchange of heavy and very accurate artillery fire; even more incredibly, the subsequent single Union casualty occurred as Anderson’s gun crews were firing a last salute before leaving their post. Private Daniel Hough of Battery E, 1st U.S. Artillery, was killed when his ammunition pile exploded while firing the 50th round of a planned 100-gun salute, becoming the first known casualty of the war. Two others in his crew were wounded, one later dying of his injuries. Anderson stopped the salute rounds and quietly began his command on a steamship bound for New York. Fort Sumter now belonged to the state of South Carolina.

Fort Sumter quickly became a symbol of the rebellion, both in the North and South, and both sides were equally determined to possess it. Literally the moment Anderson left, South Carolina troops moved in and started repairing some of the damage from the intense bombardment. The Confederates held Fort Sumter for the next 27 months, nearly to the end of the war, although there were no fewer than 2 direct assaults and 11 major bombardments against its garrison. Over the course of almost two years, as many as 46,000 shells (approximately 3,500 tons of metal) were fired at the island fort.

The First Shot

There is an ongoing controversy over who fired the “first shot” of the war. Most general histories rather blandly state that widely admired Virginia secessionist Edmund Ruffin fired this shot, usually accompanied by a really great photo of the irritable agitator sitting with his rifle, staring a hole in the camera. Ruffin was a member (probably honorary, as he was 67 years old at the time) of the Palmetto Guards and was supposedly present at Stevens Battery on Charleston Harbor that night (but even this point is open to debate).

The “official” invitee to pull the lanyard for the first shot was supposed to be congressman (later Brigadier General, even later Private when he resigned his commission and joined Lee’s army as a scout) Roger Atkinson Pryor, the former U.S. congressman from Virginia, who had endlessly preached not only for secession but for bombardment of Fort Sumter as well. “Strike a blow!” was his endless call to war, at least before he was actually given the chance. Pryor declined the invitation to fire the signal round, simply stating quietly, “I could not fire the first gun of the war.” Captain George S. James stepped forward as commander of the battery and without ceremony yanked the lanyard.

At least one source, possibly hoping to preserve the old legend, suggests that Ruffin fired the first “actual” shot from Stevens Battery after James fired the “signal” for him to do so. In opposition to all this, Shelby Foote, famed novelist-historian of the Civil War, repeats the Ruffin story in his mostly reliable and superbly written The Civil War: A Narrative.

This whole argument is simply a subset of the line of arguments that consume and delight historians. Where were the true “first shots” fired: at Fort Sumter, at Fort Barrancas in Pensacola Bay a few hours beforehand, at the USS Star of the West, elsewhere? Then, of course, there is an even bigger argument over where the first battle was fought. As you can see, historians tend to consume themselves at times over what are in all reality rather trivial points.

Edmund Ruffin

On April 7, 1863, the Union Navy mounted the first attempt to take back their fort. A squadron of eight ironclad monitors and the capital ironclad battleship USS New Ironsides, a 3,500-ton, 20-gun frigate under Rear Admiral Samuel Francis Du Pont, attempted to blast past the defenses of Fort Sumter and force open an entrance to the harbor. In what was supposed to be a coordinated and mutually supporting attack, Major General David Hunter had his troops loaded on transports just offshore, preparing to land on Folly, Cole’s, and North Edisto Islands.

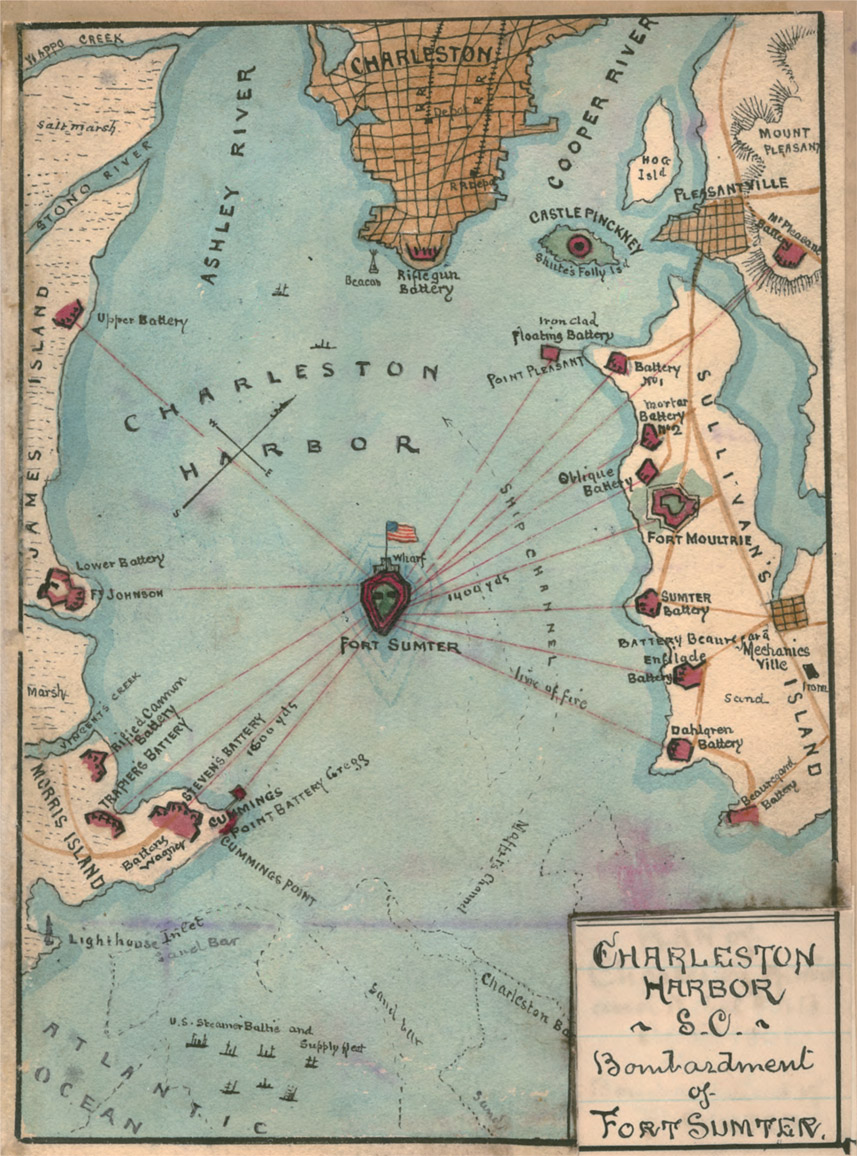

Map of the bombardment of Fort Sumter

The “battle,” as it was, did not take long. Du Pont’s small fleet sailed into the harbor, guns blazing on Confederate batteries at Fort Sumter and Sullivan Island, to no real effect. Beauregard’s batteries returned a galling fire, pounding the ironclads with well-aimed shot and shell from at least nine separate gun emplacements. The USS Keokuk would sink the next day, struck by more than 90 shots and her armored hull breached. Other ships in his squadron had suffered a total of 351 hits from the cannoneers of Fort Sumter, while only returning a grand total of 55 ineffective hits on the masonry fort. Du Pont was unable to push past Fort Sumter and soon turned back to sea, at the cost of 22 of his sailors killed or wounded. Hunter never even attempted to land his troops. Beauregard suffered the loss of 14 killed and wounded in the brief attack.

By early September 1863, with the situation improving for Union forces besieging the islands surrounding Charleston Harbor, Admiral John Adolph Dahlgren, commanding the Union blockade fleet at Charleston, somehow got the idea that Beauregard was pulling out of Fort Sumter and relayed this bit of “intelligence” to area commander Major General Quincy Adams Gillmore, who advised Dahlgren to send a force in to retake the fort.

Once again, the attack didn’t last long. The fort had not been abandoned but was instead fully manned and commanded by Major (later Brigadier General) Stephen Elliott, whose home in nearby Beaufort was being used as a Union headquarters at the time. About 1 a.m. on September 9, 1863, a force of about 400 U.S. sailors and marines rowed up to the fort’s landing, only to be greeted by heavy and accurate rifle fire from the parapets. Some Confederate defenders even tossed down small cannon shells mounted with lit fuses, an early and crude version of hand grenades.

The Union sailors and marines were totally overwhelmed, having been told not to expect any resistance at all. Within a few minutes 21 were killed or wounded, another 100 or so captured, and the rest were rowing like mad for the safety of Union-held islands. Elliott reported that he had not suffered a single casualty in the assault.

Realizing that direct assault on the well-protected post was rather unhealthy and that it was absolutely impossible to simply sail by its defenses, Gillmore determined the best course of action was to simply reduce both Fort Sumter and the city of Charleston to rubble by a heavy and prolonged artillery fire. With Morris Island now under Union control (see Battery Wagner later in this chapter), Gillmore ordered batteries to be set up and to begin firing as soon as possible. The first shots rang out on the morning of August 17, 1863, continuing unabated night and day until August 23. Other batteries gradually came into line, bombarding both the fort and the city more or less continually until both were evacuated in early 1865.

One famous siege gun was the “Swamp Angel,” an 8-inch Parrott rifled gun weighing more than eight tons and mounted on a special carriage able to “float” on the swampy soil of Morris Island. It fired a 175-pound shell with deadly accuracy, but typical of this class of artillery piece, its barrel burst on the 36th round.

Although the heavy bombardment gradually leveled the fort’s three-story walls down to a single story of casements, Confederate engineers simply used the rubble to reinforce this lowest tier, making it even more resistant to artillery fire. The fort never surrendered its garrison; with the approach of Sherman’s grand army in February 1865, both it and the city were evacuated.

During the buildup of defenses around Charleston Harbor early in 1861, a small mud redoubt was constructed on James Island near a small settlement called Secessionville. This redoubt, later dubbed Battery Lamar, was soon manned by a 500-soldier garrison, who thought that they were left out on the fringe of any action at their remote location.

General Hunter had placed two Union divisions under Brigadier General Henry Washington Benham on the southeastern portion of James Island early in June 1862, planning to use them to assault Charleston by land along the Stono River, having just learned that Beauregard had abandoned some of his outer defenses. Hunter gave strict and very specific orders to Benham not to take his force and try to assault either the city or nearby Fort Johnson until more infantry could be brought up.

Major General John Clifford Pemberton, newly appointed commander of the Confederate Department of South Carolina, Florida, and Georgia, noted the increased Union movements south of Charleston and ordered defenses there to be bolstered. Brigadier General Nathan George Evans was given command of the James Island defenses and directed to build additional earthworks and redoubts to meet the expected attack.

Battery Lamar was given a new commander, Colonel T. G. Lamar, and 350 additional artillerymen and infantry for its defense, and an additional three regiments of infantry were placed in a central location less than two hours march from any of the new defenses. Battery Lamar now mounted an 8-inch Columbiad, a 24-pounder rifled gun, another 24-pounder smoothbore cannon, and an 18-pounder smoothbore. Two 24-pounder smoothbores were placed in another redoubt on the north side of the small fort for flank protection and to act as a reserve.

During the night of June 15, Benham decided to ignore his orders and directed his divisional commanders to ready for an immediate assault on Battery Lamar. At 5 a.m. on the 16th, four regiments moving at the double-quick abreast burst out of the muddy cotton fields and quickly overran the Confederate pickets. Lamar had worked his men through most of the night trying to improve their post, and they were caught asleep when the attack began. By the time the gun crew stumbled out of their quarters and manned their guns, the Union line was less than 200 yards away.

Lamar ordered all guns to immediately open fire. The Columbiad, loaded with a canister charge, was the first to cut loose, tearing a gaping hole in the blue ranks. Soon the other guns were firing, joined by infantry coming into line on the ramparts. On the fort’s left face, three Union regiments made it to the top of the ramparts before Confederate infantry racing into position forced them back with a staggering volley fire. On the fort’s right face, the 79th New York Infantry, famous for their early-war Scottish Highlander kilt uniforms, actually made it over the ramparts and attacked the gun crews. A fierce hand-to-hand combat was broken up when Union artillery batteries zeroed in on that section of the fort, killing some of their own men and forcing the rest to withdraw.

Two more assaults proved no more successful, and Benham finally withdrew his troops a little after 9 a.m. Benham was forced to report to a furious Hunter that he had lost 685 killed, wounded, or missing. He was subsequently brought up on charges for disobeying orders and reduced in rank, which was restored later on the personal order of Lincoln. Lamar reported 204 killed, wounded, or missing in the brief action.

By the summer of 1863, capture and control of the low-slung sandbar called Morris Island was viewed as the only way Union forces were ever going to be able to batter down the defenses of Charleston. As the city was well situated at the north end of a harbor and surrounded by mile after mile of swampy lowlands, the Union Army had been unable to penetrate close enough overland to establish siege gun emplacements within range, and the Union Navy had been severely beaten back when it tried to ram its way through the waterborne defenses.

Federal battery on Morris Island

On July 10, a well-coordinated attack on Morris Island began, with Dahlgren’s ironclad squadron successfully landing Brigadier General George Crockett Strong’s 1st Brigade (1st Division, X Corps) with about 3,000 troops on the southern tip of the island, supported by artillery batteries stationed on nearby Folly Island. Advancing under heavy fire from the island’s main fortification, Battery Wagner, Strong’s men advanced to within rifle range of the sand-work fort during the night. At dawn on July 11, he personally led an assault on the fort, with his 7th Connecticut Infantry managing to gain the ramparts, but they were soon forced back with the loss of 339 men. The 1,200 Confederate defenders of the 27th South Carolina Infantry, 51st North Carolina Infantry, and 1st South Carolina Artillery under Brigadier General William Booth Taliaferro lost only 12 men in the failed assault.

Gillmore ordered more troops landed later that same day and set up siege artillery to try to reduce the fort before another assault. Twenty-six heavy artillery pieces and 10 large mortars were manhandled into place and began firing on the fort by the afternoon of July 12, supported by heavy fire from Dahlgren’s ironclads.

In what was considered a radical experiment at the time, an all-black regiment led by white officers had been formed in Boston soon after Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation—the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment. Its commander, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, was the son of a prominent and wealthy abolitionist, and two of Frederick Douglass’s sons marched in the ranks. After a rather prolonged period of training and fitting out, obstructed in no small part by widespread racism within the Union Army command structure, the 54th moved out to join Gillmore’s command in South Carolina.

Shaw’s regiment received their baptism of fire on Sol Legare Island on July 16, 1863. Confederate forces under Brigadier General Johnson Hagood swept down James Island, determined to attack the Union forces gathering on Folly Island on their flanks and drive them away from Morris Island. The 54th was standing a picket line that morning on the northernmost end of the Union line, when Brigadier General Alfred Holt Colquitt’s brigade charged across the causeway. Shaw ordered the rest of his men up, and a vicious hand-to-hand brawl erupted while Brigadier General Alfred Howe Terry struggled to get the rest of his division up to support them.

The Union forces were gradually pushed completely off James Island, with the 54th remaining engaged and acting as a rear guard the whole way. By nightfall all the Union troops were on Folly Island and preparing to move over to Morris Island.

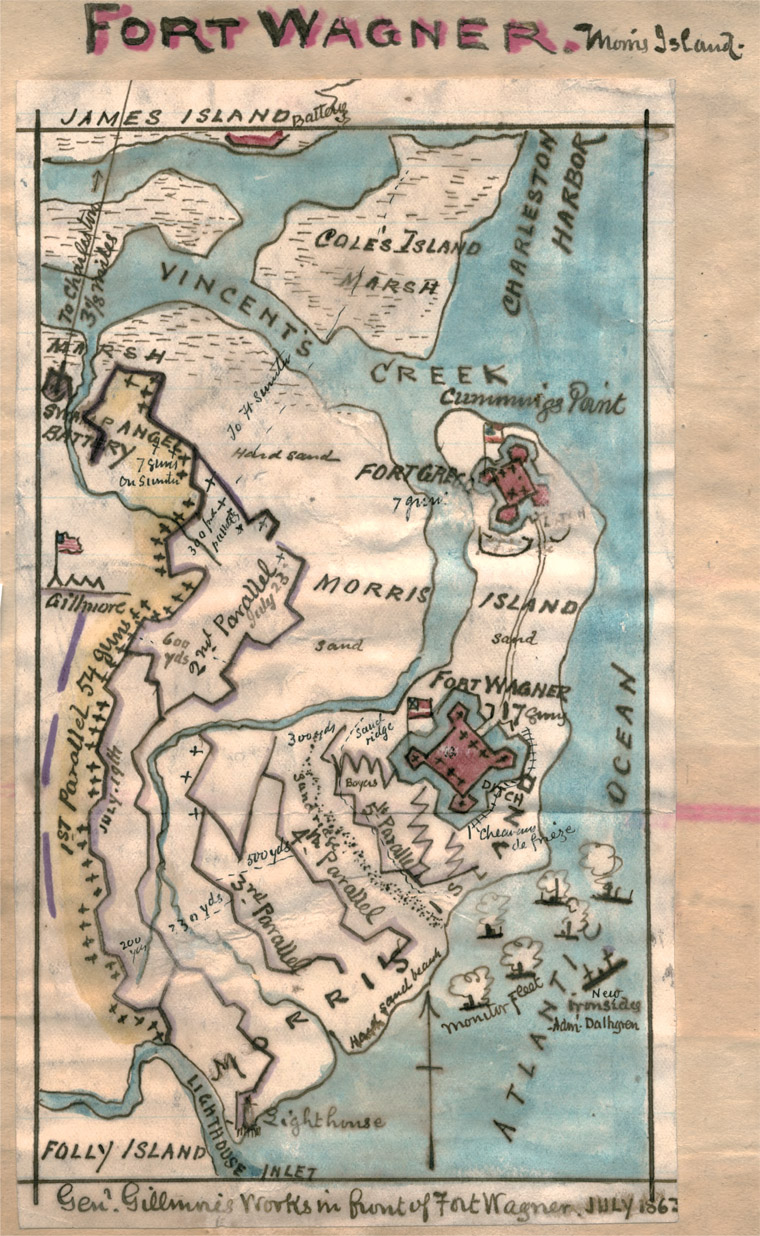

General Gillmore’s works in front of Fort Wagner in July 1863

By July 18, Gillmore decided that the massive artillery barrage had reduced the fort’s defenses down to the point where a strong assault would be successful. Brigadier General Truman Seymour’s 2nd Division was brought up in whole to take the fort, with the brigades of Strong and Brigadier General H. S. Putnam to lead the assault. The 54th was selected by Strong to be the spearhead regiment, to be followed closely by two other infantry regiments, with Putnam’s brigade of three regiments close behind them.

The reason for the single-regiment frontal assault was simple: The only access to the fort, which spread nearly completely across Morris Island, was down a narrow strip of sand between the ocean and a swamp and then across a water- and abatis-filled moat before the men could even approach the walls.

Just before dusk on July 18, the 54th formed up in ranks and moved off down the beach toward the fort. The weeklong artillery barrage had failed to significantly damage the Confederate fort, however, and as the Union infantry approached, Taliaferro’s men swarmed out of their bomb-proofs and manned their guns.

The assault was an unqualified disaster. Although a few of Shaw’s men managed to fight their way through the outer defenses and gain the ramparts, they soon were shot down and the rest of his regiment hurled back. Shaw was killed in the assault, as well as nearly half his men. The rest of Strong’s brigade fared no better; no other regiment managed to gain the ramparts, and five of the six regiment commanders were killed or wounded. Seymour himself was seriously wounded, and Putnam was killed in the attempt. In all, the Union forces suffered a total of 1,515 casualties out of the 5,300-man assault force. Taliaferro, reporting the loss of 174 killed and wounded in the attack, still held the fort.

Taliaferro and his men stayed in the sand-work fort, trading artillery fire with the Union Army and Navy, until September 1863, when Union reinforcements landing nearby made it clear the fort was about to be taken at any cost. Taliaferro then abandoned his post and moved his men back into Charleston. The battered remnants of the 54th were eventually refitted and reinforced, and the regiment stayed in service through the rest of the war, fighting primarily in Florida. The question as to whether African-American men could fight had been decisively answered, though at a terrible cost.

After the fall of Savannah in December 1864, Sherman wasted little time in turning his attention northward. Entering South Carolina with 63,000 men arranged in four great columns in late January 1865, almost no Confederate force was available to stand up against him. A single division under Major General Lafayette McLaws did their best at the Salkehatchie River Bridge east of Allendale, but all they managed to do was hold up one Union corps for a single day, at the cost of 170 men killed or wounded.

As Sherman’s “bummers” ravaged through the middle of the state, Lieutenant General William Joseph Hardee, now in command of Confederate forces around Charleston, determined that he would have to immediately evacuate his troops or risk having them cut off and trapped between Sherman and the Union Navy. On the night of February 17, 1865, with the bulk of Union forces still several days away, burning Columbia, Hardee ordered Fort Sumter abandoned and marched out of the city heading for Cherhaw to support General Joseph Eggleston Johnston’s Army of Tennessee, now in North Carolina and preparing for last-ditch defenses.

Sherman never moved toward Charleston, instead moving his grand army slowly northeast toward North Carolina, meeting almost no resistance along the way. Charleston’s mayor surrendered the city a few days later to a handful of Union officers who had ridden up from Beaufort. The “grand affair,” which had started out with so much grand talk and excitement less than four years before, came to a quiet end.

The Battery

One can argue that Charleston’s White Point Gardens, which most people know as The Battery, shouldn’t officially be called an “attraction,” like a museum or a fort. On the other hand, it’s a darn good bet that no first-time visitor to the city ever left here without making it a point to walk there or at least drive by.

In a city where almost every other building or street holds some historical significance, few sites afford a better view of Charleston’s 300-year-long parade of history than The Battery.

That seaside corner of land at the end of East Bay Street, where it turns and becomes Murray Boulevard, is now a pleasant park with statues and monuments, long-silent cannon, and spreading live oak trees. There’s even a Victorian bandstand that looks as if it could sport a uniformed Sousa band any Sun afternoon. But the atmosphere on The Battery hasn’t always been so serene.

The Battery has been a prominent feature in Charleston since the earliest days of the English settlement. Then it was known as Oyster Point because it was little more than a marshy beach covered in oyster shells—bleached white in the Carolina sun.

At first, it was mostly a navigational aid for the sailing vessels going into and out of the harbor. The peninsula was still unsettled, and the first colonial effort was farther upstream on the banks of the Ashley River at what is now called Charles Towne Landing. Later, when the settlement was moved to the much more defensible peninsula site, the point was a popular fishing area, too low and too easily flooded to be much of anything else. Charts used during the years 1708 to 1711 show only a “watchtower” on the site and just a few residences built nearby.

Remember, Charles Towne was still a walled city at that time, the southernmost wall being several blocks north, near what is now the Carolina Yacht Club on East Bay Street. The point was definitely a “suburban” location. The area took a decidedly higher public profile about a decade later, when pirate Stede Bonnet and some 40 or 50 scalawags like him were hanged there from makeshift gallows. The local authorities must have gotten the right ones, as they were apparently quite effective in bringing an end to the pirate activity that had plagued the Carolina coast.

The first of several real forts built on the site came along as early as 1737. This and subsequent fortifications were crudely built, however, and none lasted long against the tyranny of the sea. By the time of the American Revolution, White Point was virtually at the city’s door and no longer considered a strategic site for defense.

Hurricanes in 1800 and again in 1804 reduced whatever fortification remained there to rubble. Another fort, this version constructed for the War of 1812, apparently gave White Point a popular new name: The Battery. At least, the new name appears on maps beginning about 1833.

The seawall constructed along East Battery (the “high” one) was built after a storm in 1885. Storms and repairs have traded blows at the seawall for many years: in 1893, 1911, 1959, and, of course, with Hugo in 1989.

The area’s use as a park dates back to 1837, when the city rearranged certain streets to establish White Point Gardens. It was from this vantage point that Charlestonians watched the battle between Confederate fortifications across the river and the small band of Union troops holed up in Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861. Once the war had started, this peaceful little garden was torn up and convulsed into two massive earthwork batteries, part of Charleston’s inner line of defense. And while one of these battery sites housed a Blakely rifle (a 3.50 caliber rifled cannon that fired a variety of specially flanged shot and shell in the 12-pound range), neither battery ever fired a shot in anger. (Some incoming artillery rounds landed here during the extended bombardment of the city from late 1863 until Charleston fell in February 1865.)

The end of the Civil War was the end of The Battery’s role in Charleston’s military defense, although several subsequent wars have left poignant souvenirs behind for remembrance. Today no fewer than 26 cannon and monuments dot The Battery’s landscape, each of which is described on a nearby plaque or informational marker.

Battery Wagner

Morris Island, SC

www.morrisisland.org

Of all the forts and battlegrounds that dot the Low Country landscape and pay quiet tribute to the area’s military history, perhaps the most muted one is Battery Wagner. The story is a brief one in the long struggle of the Civil War, but it is a significant one that is especially poignant today. In 1989 the story of Battery Wagner was portrayed in the acclaimed film Glory, which starred Matthew Broderick, Denzel Washington, and Morgan Freeman.

Time and tides have long since removed all traces of Battery Wagner. Today Morris Island is vacant and uninhabited. It was annexed by the City of Charleston and is expected to one day be developed to become a vital part of the ever-growing metropolitan area surrounding the city. Although a monument at Battery Wagner is planned, the site remains remarkably overlooked by the public at large. But whatever its future may hold, the story of Morris Island will always include the story of Battery Wagner and the 54th Massachusetts Regiment.

The Charleston Museum

360 Meeting St.

Charleston, SC

(843) 722-2996

www.charlestonmuseum.org

Directly across Meeting Street from the Visitor Reception and Transportation Center is one of Charleston’s finest jewels: the Charleston Museum. Because it is the first and oldest museum in America, having been founded in 1773, the museum’s collection predates all modern thinking about what should be kept or discarded in preserving the artifacts of a culture. The Charleston Museum operates three facilities: the Main Museum, the Heyward-Washington House, and the Joseph Manigault House.

The main museum’s scope is the social and natural history of Charleston and the South Carolina coastal region. Objects from natural science, cultural history, historical archaeology, ornithology, and ethnology are presented to illustrate the importance each had in the history of this area. The Charleston Silver Exhibit contains internationally recognized work by local silversmiths in a beautifully mounted display. Pieces date from colonial times through the late 19th century.

Visitors will see what the museum’s many archaeological excavations have revealed about some of the city’s best and worst times. Some artifacts date from the early colonial period, while others are from the Civil War years. Some exhibits focus on early Native Americans who lived in this region. Others trace changes in trade and commerce, the expansive rice and cotton plantation systems, and the important contributions made by African Americans.

Children will be intrigued by the KidStory exhibits, with amazing things to touch, see, and do. They’ll see toys from the past, games children played, the clothes they wore, furniture they used, and more. The photographs, ceramics, pewter, and tools reveal a very personal portrait of Charlestonians from the past.

The two houses operated by the Charleston Museum give visitors two examples of fine homes and furnishings during various times in American history.

For those wishing to visit two or more of the sites, discounted adult admission is available.

Fort Johnson

South Carolina Department of Natural Resources

217 Fort Johnson Rd.

Charleston, NC

(843) 953-9300

www.dnr.sc.gov/marine/mrri/ftjohnson.html

Fort Johnson is another Charleston-area fortress steeped in history and adaptively reused for modern needs. Since the early 1970s, the waterfront James Island site has been the home of the South Carolina Marine Resources Research Institute, which researches and promotes the state’s marine industries. But military buffs know Fort Johnson in another role. Like Fort Moultrie, this site has military significance that dates back several hundred years.

No trace now exists of the original Fort Johnson that was constructed on the site in about 1708. It was named for Sir Nathaniel Johnson, proprietary governor of the Carolinas at the time. A second fort was constructed in 1759, and small portions of that structure remain as “tabby” ruins there today. (Tabby is an early building material made from crushed lime and oyster shell.)

Records show the fort was occupied in 1775 by three companies of South Carolina militia under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Motte. During the American Revolution, the fort remained in colonial hands until 1780, when the British forces advancing on Charleston reported finding it abandoned. A third fort was built in 1793, but a hurricane destroyed it in the 1800s. Some work on Fort Johnson was done during the War of 1812, but the following year another storm destroyed that progress. Shortly afterward, Fort Johnson was dropped from official reports of U.S. fortifications.

During early 1861, South Carolina state troops erected mortar batteries and an earthwork of three guns on the old fortress site. The signal shot that opened the bombardment of Fort Sumter and marked the beginning of the Civil War was fired from the east mortar battery of Fort Johnson on April 12, 1861.

All throughout the Civil War, building activity increased until Fort Johnson became an entrenched camp mounting 26 guns and mortars. However, apart from routine artillery firing from the site, the only major action at the fort occurred on July 3, 1864, when its Confederate defenders repulsed two Union regiments totaling about 1,000 men. The Union forces sustained 26 casualties and lost 140 men as captives. The Confederate loss was 1 killed and 3 wounded. On the night of February 17, 1865, Fort Johnson was evacuated during the general Confederate withdrawal from Charleston Harbor.

After the Civil War, Fort Johnson became a quarantine station operated by the state and the city of Charleston. It continued to be used in that capacity until the 1950s. Today’s inhabitants at the site (the Marine Resources folks) do not prohibit exploration, so you might find this history-drenched spot worth a visit.

Fort Moultrie

1214 W. Middle St.

Sullivan’s Island, SC

(843) 883-3123

www.nps.gov/fosu/historyculture/fort_moultrie.htm

From the earliest days of European settlement along the eastern seaboard, coastal fortifications were set up to guard the newly found, potentially vulnerable harbors. In this unique restoration, operated today by the National Park Service, visitors to Fort Moultrie can see two centuries of coastal defenses as they evolved.

In its 171-year history (1776 to 1947), Fort Moultrie defended Charleston Harbor twice. The first time was during the Revolutionary War, when 30 cannon from the original fort drove off a British fleet mounting 200 guns in a ferocious, nine-hour battle. This time, Charleston was saved from British occupation, and the fort was justifiably named in honor of its commander, William Moultrie. The second time was during the long Union siege of Charleston.

Today the fort has been restored to portray the major periods of its history. Five different sections of the fort and two outlying areas each feature typical weapons representing a different historical period. Visitors move steadily back in time from the World War II Harbor Entrance Control Post to the original, palmetto log fort of 1776.

Groups should make reservations for guided tours. Pets are not allowed inside the building, but are allowed on the grounds with a leash. A family rate is available.

From Charleston, take US 17 North (Business) through Mt. Pleasant to Sullivan’s Island and turn right on Middle Street. The fort is about 1½ miles from the intersection.

Fort Sumter National Monument

Charleston Harbor, SC

(843) 883-3123

www.nps.gov/fosu

Today Fort Sumter is a national monument administered by the National Park Service of the U.S. Department of the Interior. It is still accessible only by boat, and the only public tour of this tiny man-made island and world-famous fort is offered through Fort Sumter Tours. You can board the Fort Sumter tour boat at either Liberty Square in downtown Charleston or Patriot’s Point Naval and Maritime Museum in Mt. Pleasant (across the Cooper River). The two-and-a-quarter-hour tour consists of approximately 35 minutes of narration while cruising the historic Charleston Harbor, one hour at Fort Sumter, and then 30 minutes of narration on the return trip.

The trip affords delightful views of Charleston’s waterfront and the tip of the peninsula from an ocean voyager’s perspective. (There’s a separate, one-and-a-half-hour tour that does not stop at the fort and includes a cruise under the Cooper River bridges on up to the vast facility that until recently was the U.S. Naval Base in North Charleston.) The specially built sightseeing boats are clean and safe and have onboard restrooms.

Once you’re at Fort Sumter itself, you can walk freely about the ruins. There’s a museum on-site with fascinating exhibits of the fort’s history. National Park Service rangers are there to answer any questions you may have.

You’ll need to check in for your tour at least 25 minutes early for ticketing and boarding. Departure times vary according to the season and the weather, so call for departure information (843-722-2628 or 800-789-3678). During the busy summer season, there are usually three tours a day from each location. Wheelchair access is available only at the Liberty Square departure location. Group rates are available, but advance reservations for groups are encouraged.

Magnolia Cemetery

70 Cunnington St.

Charleston, SC

(843) 722-8638

www.scocr.org/Links/MagnoliaCemetery.htm

One of the most telling places in all Charleston has to be the remarkably distinctive 19th-century cemetery at the north end of the peninsula, not far off East Bay Street/Morrison Drive.

Not on any contemporary beaten path and clearly not a tourist destination, Magnolia Cemetery is the quiet, final resting place of many important Charlestonians and other players in the city’s long-running and colorful drama. It is also an intriguing collection of Southern funerary art in an almost unbearably romantic setting, yet another eloquent expression of Charlestonian pride and prejudice.

The site was originally on the grounds of Magnolia Umbria Plantation, which dates back to 1790. Rice was the principal crop here in the first half of the 19th century. By 1850, however, a 181-acre section of that land had been surveyed for a peaceful cemetery, dedicated on November 19, 1850, on the edge of the marsh. From that time on (even to the present), many of Charleston’s most prominent families chose Magnolia as the place to bury and commemorate their loved ones.

Many of the city’s leaders, politicians, judges, and other pioneers in many fields of endeavor are interred beneath the ancient, spreading live oaks of Magnolia. Among them are five Confederate brigadier generals. There is a vast Confederate section, with more than 1,700 graves of the known and unknown. Eighty-four South Carolinians who fell at the Battle of Gettysburg are included.

There are literally hundreds of ornate private family plots, many of which bear famous names. You will find the monument of Robert Barnwell Rhett—”Father of Secession,” U.S. senator, attorney general of South Carolina, and author. There’s also the grave of George Alfred Trenholm, wealthy cotton broker who served as treasurer of the Confederacy and organized many a blockade run for the cause. Trenholm is thought by many to be the man on whom Margaret Mitchell’s Rhett Butler was based for Gone with the Wind. Among the famous artists and writers buried in Magnolia are Charleston’s Alice Ravenel Huger Smith and John Bennett.

To find Magnolia, drive north on East Bay/Morrison Drive and turn right at the traffic light onto Meeting Street/SC 52. Turn right at the first opportunity onto Cunnington Street; Magnolia’s gates are at the end of the street. Call for current hours before a visit.

Powder Magazine

79 Cumberland St.

Charleston, SC

(843) 722-9350

www.powdermag.org

Only a couple of blocks from the bustling market area is, quite simply, the oldest public building in the Carolinas. And yet, as Charleston attractions go, the Powder Magazine is relatively unknown to tourists and to some locals as well.

Perhaps the site is overlooked because it’s dramatically upstaged by Charleston’s sumptuous house museums and romantic streetscapes. And in truth, the utilitarian Powder Magazine actually predates Charleston’s legendary aesthetics. It was built for a time when the still-new English settlement was predominantly interested in self-defense and basic survival.

In the early years of the 18th century, Charles Towne was still threatened by Spanish forces, hostile Indians, rowdy packs of buccaneers, and an occasional French attack. It was still a walled city, fortified against surprise attack.

In August 1702 a survey of the armament in Charles Towne reported “2,306 lbs. of gunpowder, 496 shot of all kind, 28 great guns, 47 Grenada guns, 360 cartridges, and 500 lbs. of pewter shot.” In his formal request for additional cannon, the royal governor requested “a suitable store of shot and powder … (to) make Carolina impregnable.” And so in 1703 the Crown approved and funded such a building, which was completed in 1713 on what is now Cumberland Street.

The Powder Magazine was the domain of the powder receiver, a newly appointed city official entitled to accept a gunpowder tax levied on all merchant ships entering Charleston Harbor during this period.

The building served its originally intended purpose for many decades. But eventually, in an early colonial version of today’s base closings, it was deemed unnecessary (or too small) and sold into private hands.

This multi-gabled, tile-roofed architectural oddity was almost forgotten by historians until the early 1900s. In 1902 it was purchased by the National Society of Colonial Dames of America in the State of South Carolina. It was maintained and operated as a small museum until 1991, when water damage, roof deterioration, and time had finally taken too high a toll. What the Powder Magazine needed to survive at all was a major stabilization and restoration—something beyond the resources of the owners.

In an agreement whereby Historic Charleston Foundation did the needed work under a 99-year lease, the Powder Magazine underwent a $400,000 preservation effort, its first ever. This included a temporary roof over the entire structure, allowing the massive walls to dry out before necessary repairs could even begin. Much-needed archaeological and archival research was also done on the site.

The Powder Magazine opened to the public in the summer of 1997. Inside, an interactive exhibit interprets Charleston’s first 50 years, a time when it was still a relatively crude colonial outpost of the British Empire.

Secessionville

Fort Lamar

James Island, SC

(803) 734-3893

www.csatrust.org/secessionville.html

While the small settlement has disappeared without a trace (the area is now a subdivision called Secessionville Acres), the earthwork fort is now a South Carolina Heritage Preserve and is undergoing preservation and restoration efforts by volunteers. A reenactment of the Battle of Secessionville is held annually.

To get to the site, drive south out of Charleston on US 17, and turn left onto Folly Road (SC 171) just past the Ashley River Bridge. Turn left onto Grimball Road, right onto Old Military Road, and almost immediately left again onto Fort Lamar Road. The preservation site is about 1¼ miles down the road on the left. Hours are one hour before dawn to one hour after dusk. Free admission. See the Web site www.battleofsecessionville.org for upcoming events and reenactments.

As nearly all the significant Civil War sites are in and around Charleston, we have limited our suggestions for hotels/motels and restaurants to this city.

A friendly word of advice: Charleston attracts droves of visitors year-round, and we strongly recommend that you make reservations well in advance. For major events like Spoleto and holiday weekends, it’s advisable to think up to six months in advance.

| Charleston Place Orient Express | $$$$ |

205 Meeting St.

Charleston, SC

(843) 722-4900

(888) 635-2350

In terms of size, the former Omni is the granddaddy of Charleston hotels, with 444 units sprawling across a massive complex in the shopping district. The hotel, with its impressive lobby and reception area, opens into the walkway of a mini-mall that includes such famous stores as Godiva, St. John’s, and Gucci. The on-site spa is open to hotel and day visitors and offers an indoor-outdoor rooftop swimming pool, fitness equipment, and a children’s splash pool. Under the auspices of Orient Express, the rooms at Charleston Place are taking on the aura of Europe in the 1930s. Expect to find marble bathtubs and gold fixtures in the roomy baths. And notice the little touches in the rooms like art deco lighting and the subdued use of color. It adds just that much more romance to your lodging experience.

Several superb dining options are available right under the Charleston Place roof. Foremost among them is the Charleston Grill, tucked away among the shops and boutiques.

| Doubletree Guest Suites at Charleston–Historic District | $$$$ |

181 Church St.

Charleston, SC

(843) 577-2644

Located in The Market area, Doubletree Guest Suites is a comfortable courtyard hotel consisting of oversize suites. Units have “the Charleston look” and include complete kitchens, separate bedrooms, and living rooms. Life is made easy with a complimentary breakfast buffet, and for those who enjoy burning the calories they consume, there’s a fitness center in the courtyard that seats at least 12 comfortably (great for relaxing while gazing at the stars). When energy levels diminish, the hotel’s VCR tape library is available to complement your cable television service.

| Mills House Hotel | $$$$ |

115 Meeting St.

Charleston, SC

(843) 577-2400

(800) 874-9600

The original structure was built in 1853 and was also the site for the funeral of Horace Hunley, the Confederate marine engineer who designed early submarines. The structure burned in the Great Charleston Fire of 1861, but was rebuilt. The original balcony remained and is still part of the hotel’s outer decor today. This full-service hotel is not only filled with history, but also fine dining and an art gallery for guests’ enjoyment.

| Hyman’s Seafood, Aaron’s Deli, Hyman’s Half Shell | $$ |

215 Meeting St.

Charleston, SC

(843) 723-6000

A casual seafood dining experience for lunch or dinner, Hyman’s offers a large selection of fresh-caught fish and a wide variety of shellfish. A raw bar and lounge are upstairs. Hyman’s fries in 100 percent soybean vegetable oil. Try the fried okra or the Low Country gumbo, even if you have always shied away from the vegetable. The she-crab soup is award-winning. We suggest parking in the Charleston Place garage.

| Tommy Condon’s Irish Pub and Seafood Restaurant | $–$$ |

160 Church St.

Charleston, SC

(843) 577-3818

The most authentic Irish pub in Charleston, Tommy Condon’s has “live” Irish entertainment and serves a wide variety of imported beers and ales such as Bass and Newcastle Brown. The menu is a mixture of Irish and Low Country items including shrimp and grits, seafood jambalaya, and fresh fish of the day. There is a covered deck for outside dining, and patrons are welcome for lunch or dinner any day of the week.