Nashville and Franklin: Destruction of the Confederate Armies in Tennessee

On a short list of all the boneheaded maneuvers during the Civil War, General John Bell Hood’s invasion of Tennessee for the Confederacy in late 1864 without a doubt ranks at or near the very top. Possibly influenced by his reported use of large doses of laudanum as a pain reliever for his serious injuries from Gettysburg and Chickamauga, Hood concocted this plan after being thoroughly trounced by Major General William T. Sherman’s three grand armies around Atlanta in the late summer of 1864.

Maintaining to his death that the only way to defeat Sherman was to draw him into battle on terrain of his own choosing (possibly true), Hood decided to take what was left of his Army of Tennessee and march north out of the Atlanta area, “forcing” Sherman to follow and then defeating him by parts as the Union armies marched after him.

In May 1864 three grand armies with a total of 110,123 men and 254 cannon under Sherman marched south out of their winter quarters at Chattanooga, Tennessee, aiming for the heart of the Southern Confederacy, Atlanta. Standing in their way was General Joseph Eggleston Johnston with a single army of 54,500 men and 144 artillery pieces. Within four months, Sherman tore a path through northwest Georgia, resoundingly defeated the Confederate Army in nearly every battle, besieged Atlanta, and finally took the city when the last defenders slipped out during the night of September 1.

Johnston was a defensive genius, probably delaying the inevitable far longer than any other Southern general could have. His primary handicaps, ironically, had nothing to do with his overt enemy, Sherman, but lay in the enmity of President Jefferson Davis’s military advisor, General Braxton Bragg, and one of his own corps commanders, Hood. Both conspired against Johnston behind his back to Davis, making outrageous charges that he was “reluctant to fight” and that his tactics would lead to ruin. Davis was all too willing to listen; although Bragg had proved a disaster as an army commander, and even General Robert E. Lee warned that Hood was out of his league above a corps command (and others warned he wasn’t particularly good at that position, although a capable and outstanding divisional commander), Davis held a grudge against Johnston. The exact reason for this enmity is open to debate, but most likely it resulted from political infighting at the very beginning of the Confederate government.

General Joseph Eggleston Johnston

When Johnston was finally forced south of the Chattahoochee River just north of Atlanta, Davis mocked outrage at this act of “incompetence” and promptly fired him. Placed in his stead was Hood, who promised to go on the offensive, and whose appointment dashed the morale of the men he was to lead. Johnston had been their hero, a man they trusted and who trusted in them as well, who had placed their lives above holding property, and who had been forced to withdraw nearly a hundred miles but had done it without leaving behind any command or even a single artillery piece.

Braxton Bragg

Perhaps one of the most hated and vilified men in the entire Confederate Army, Braxton Bragg’s greatest advantage as a military commander was his close friendship with President Jefferson Davis. Born on March 22, 1817, in North Carolina, Bragg graduated high in his class at West Point in 1837 and served with Davis in the Mexican War before resigning from the army to start a plantation in Louisiana.

When the war began, Bragg served first as a high-ranking officer in the Louisiana militia before being tapped for duty as a Confederate general officer in charge of part of the Gulf Coast defenses. Soon promoted to major general, he was transferred to A. S. Johnston’s command at Corinth and commanded a corps at Shiloh. Thanks to his close friendship with Davis, Bragg was soon promoted to full general and given command of the Army of Tennessee. Despite his earlier heroics (mostly in the Seminole and Mexican-American Wars) and his relative competence as a corps commander, Bragg was a near unmitigated disaster as an army commander. Serious defeats followed his invasion of Kentucky, the fights at Perryville and Stones River, and his actions during the Tullahoma Campaign. A resounding victory at Chickamauga can be traced not strictly to his battlefield strategy, but more to the timely arrival of Major General James Longstreet’s corps and a simultaneous Union defensive blunder.

Just after the battle at Chickamauga, Bragg returned to his usual form, refusing against strong protest to pursue the crushed Union Army (he was deathly afraid of running headlong into a possible Union ambush) and allowing it time to regroup. A subsequent and complete defeat at Chattanooga finally resulted in his loss of command for good; his actions there were so incompetent that Davis could no longer overlook them. His removal from command brought great celebration in the ranks, reinforced when the beloved J. E. Johnston was placed in his stead. Davis placed Bragg as his chief of staff, where he continued to plague the Confederate armies with a series of interfering moves, unnecessary commands and directives, and political retaliations. At the very end of the war, he returned to combat duty and served as a divisional commander under J. E. Johnston at the Battle of Bentonville.

Bragg’s postwar life was no more successful than his wartime life. He served briefly as the chief engineer for the state of Alabama before moving on to Galveston, Texas. He died there on September 27, 1876, suddenly struck by a stroke while walking down the street. Few postwar memoirs have the slightest positive comments about him—other than proclaiming his devotion to the Confederate cause; perhaps the kindest comments are that he was an able and effective organizer and staff officer. His defenders admit to a person that his battlefield accomplishments were few and far between but point out that he suffered from chronic migraine headaches and was often ill, sometimes quite seriously, from other causes during his campaigns.

Hood, on the other hand, was well known for his “battlefield heroism,” actions that played well in the press but tended to get a lot of his own men killed for no real gain. His charges at Devil’s Den at Gettysburg in July of 1863 had lost him the use of an arm, and his charge on the second day at Chickamauga a little more than two months later cost him his right leg. He carried this same flair for dashing off into the face of the enemy into his leadership of the Army of Tennessee, which he ordered on the offensive the same day he assumed command, July 17, 1864.

On July 20, 1864, Hood ordered an assault at the Battle of Peachtree Creek, just north of Atlanta. Two days later he tried another assault at the Battle of Atlanta, actually a few miles east of the city, and on July 28 he tried yet another at the Battle of Ezra Church, west of Atlanta. The only result in three actions was to reduce his fighting force to fewer than 37,000, with a few thousand Georgia militiamen thrown in for good measure. A final series of battles at Jonesboro shattered his own army, and Hood promptly abandoned Atlanta. Sherman’s armies walked in unmolested on September 2.

Battle of Jonesboro

Davis “encouraged” Hood to attack Sherman and recapture the city, but that overwhelming task daunted even the “attack at all costs” Texan. Instead, he proposed to march north of the city to strike and cut Sherman’s supply line from Chattanooga, which, hopefully, would force the Union Army out of the city and north in pursuit. Although neither Hood nor Johnston had yet decisively defeated Sherman in a major pitched battle the entire campaign, with the Southern army intact, he now convinced the Confederate president that by choosing his defensive terrain carefully, he could defeat a well-armed, well-equipped, and relatively fresh force four times his size. Amazingly, Davis bought the idea and approved the plan.

With three corps in his command, led by Major General Benjamin Franklin “Frank” Cheatham, Lieutenant General Stephen Dill Lee, and Major General Alexander Peter Stewart, a cavalry corps commanded by Major General Joseph “Fighting Joe” Wheeler, and a separate cavalry division commanded by Brigadier General William Hicks “Red” Jackson, Hood moved out of his last Atlanta base of Lovejoy on September 18, swinging wide around the western flank of the Atlanta defenses, and headed north. Sherman had anticipated the maneuver and had already sent Brigadier General George Henry Thomas (the “Rock of Chickamauga”) with three infantry divisions back to Chattanooga to prepare.

Hood moved relatively slowly, crossing the Chattahoochee River near Campbellton on October 1. He continued north for two days, finally encamping near Hiram. Stewart was ordered to move east and attack and cut the Western & Atlantic Railroad line at Big Shanty (now Kennesaw), Acworth, and Allatoona.

Stewart’s men surprised and captured about 170 Union troops at Big Shanty on October 4 and then quickly moved north and captured a larger garrison at Acworth. Flushed with these easy successes, Hood personally ordered Major General Samuel G. French to take his division on up the tracks to capture and destroy the bridge and railroad cut at Allatoona Pass in Georgia. Hood was under the impression that the pass was only lightly held, as the two previous rail stops had been. However, Sherman had made the tiny settlement on the south side of the deep railway cut into a central base of logistical operations, had it heavily fortified, and had ordered another division under Brigadier General John M. Corse forward to garrison it. On both peaks over the 90-foot-deep railroad cut, heavily reinforced emplacements had been built. The westernmost set of peak defenses was dubbed the Star Fort, because of the arrangement of railroad ties surrounding it.

French divided his force and approached Allatoona from the north, west, and south. Once all were in position, he rather arrogantly sent Corse a terse message:

Sir: I have the forces under my command in such positions that you are now surrounded, and, to avoid a needless effusion of blood, I call upon you to surrender your forces at once, and unconditionally. Five minutes will be allowed for you to decide. Should you accede to this, you will be treated in the most honorable manner as prisoners of war.

Corse was somewhat less than impressed, and 15 minutes later he replied, “Your communication demanding surrender of my command, I acknowledge receipt of, and respectfully reply, that we are prepared for the ‘needless effusion of blood’ whenever it is agreeable with you.”

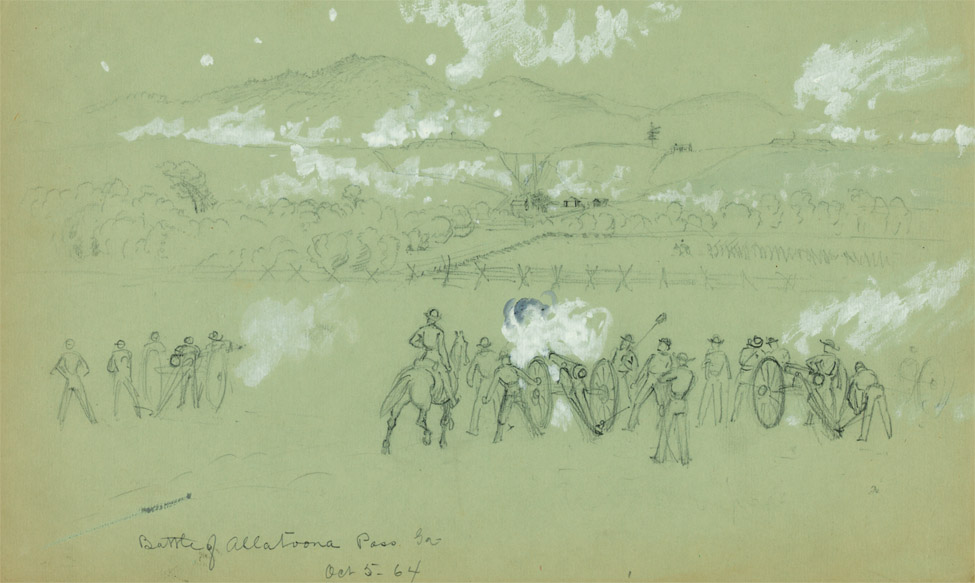

Allatoona Pass

French wasted no time in sending Brigadier General Francis M. Cockrell’s Missouri Brigade and Brigadier General William H. Young’s (Ector’s) Brigade to assault from the west. Both pushed through the first line of defense, then the second, and then through a third line of defense, all the while fighting hand to hand with clubbed rifles and bayonets. Advancing to within a few feet of the Star Fort, the fighting rapidly intensified, with the Confederate advance finally being stopped before it could overrun the fort. With warnings coming from outposts that a Union force had been spotted moving rapidly toward the battle area, French disengaged and marched his depleted force west to rejoin Hood.

All through the daylong battle, a Union signal post at Kennesaw Mountain sent a message to Corse: “General Sherman says hold fast; we are coming.” This message, which popularized the expression “hold the fort,” was nothing more than a morale booster, for Sherman did not order any additional infantry to the area until the next day, and none arrived until two days later. The forces spotted by the Confederate side were apparently just cavalry on a scouting mission.

Casualties in this little-remembered battle were exceptionally high, with Corse reporting 706 dead and wounded, and French also reporting 706 (including 70 officers), about 30 percent of either side’s total force. Young himself was wounded just outside the fort and captured shortly afterward. Corse reported in a message to Sherman that he, too, had been wounded: “I am short a cheek bone and an ear but am able to lick all hell yet!” When Sherman came up later, he was unimpressed with the severity of his wounds and said, “Corse, they came damn near missing you, didn’t they?”

Getting to Allatoona Pass

The battlefield is accessible from I-75 north from Atlanta. Take exit 283 (Emerson-Allatoona Road), turn right (east), and go about 2 miles to the pass area. On the way you will cross over a set of railway tracks, which are the modern relocation of the tracks the soldiers were fighting over.

Nearly all the area covered by the battle is today heavily overgrown or equally heavily developed, and the east side of the battlefield is under the murky waters of Lake Allatoona. The dug railroad gap is heavily overgrown, and it is difficult to get a clear picture of the tactical situation, but at least one period structure remains. The Mooney House, the yellow-and-white tin-roofed structure in the sharp curve in the road at the pass entrance, was used as a field hospital during the battle and can be seen in a famous photograph of the area by George M. Barnard taken just after the battle.

There is a small parking area with two historic markers across the street from the Mooney House, which indicate quite well the 1864 layout and tactical situation. One contains a fair reproduction of the Barnard photo, which pictures landmarks still visible today. The Star Fort is still present, although overgrown and in deteriorating condition on top of the left peak of the railway cut. A warning: Both the fort and the Mooney House are private property and not open to the public. Please be respectful and observe them from the parking lot. The eastern redoubt, on top of the right peak, is on U.S. Army Corps of Engineers property and can be accessed by a steep, partially overgrown path just inside the entrance to the pass walking north.

Following the decisive loss at Allatoona Pass, Hood elected to continue north, moving west around Rome through Cedartown, Cave Springs, and Coosaville, while Sherman moved north after him with a force of 40,000 men (55,000 in some accounts), a partial vindication of Hood’s audacious plan. Wheeler’s cavalry joined the campaign at this point, screening his movement from Sherman’s force, while Jackson’s cavalry stayed below Rome near the Coosa River. Attacks at Resaca on October 12 and 13 were failures, but Lee’s and Cheatham’s corps were able to capture the railroad north of Resaca the next day. In one of the only real successes in north Georgia, the 2,000-man Union garrison at Dalton was forced to surrender, but with Sherman hot on his heels, Hood was unable to hold the city.

Hood moved west again toward northwestern Georgia near the Alabama state line, setting up a line of battle near LaFayette on October 15. Hood’s strategy here is uncertain, as he was moving away from the mountainous terrain he had claimed would be to his advantage. There are mountains here, and rugged ones in places, but this was the same area in which Sherman had already demonstrated an ability to operate. The northeastern mountains were not specified in Hood’s plans but were his most likely original destination. If his plan was to keep Sherman bottled up in northern Georgia, it both succeeded and failed.

When Hood slipped away after the Union troops deployed for battle at LaFayette on October 17, Sherman remarked that Hood’s tactics were “inexplicable by any common-sense theory … I could not guess his movements as I could those of Johnston.” After a total of three weeks of chasing the now fast-moving Confederate Army of Tennessee, Sherman ordered his forces to return to Atlanta and prepare for a march to the south.

Warned by Grant that Hood was taking his army north into Tennessee to threaten his supply lines, Sherman remarked, “No single force can catch Hood, and I am convinced that the best results will follow from our defeating Jeff Davis’s cherished plan of making me leave Georgia by maneuvering.”

At the same time, Davis was begging Hood “not to abandon Georgia to Sherman but defeat him in detail before marching into Tennessee.” Hood replied that it was his intent to “draw out Sherman where he can be dealt with north of Atlanta.” In his postwar memoirs, Hood clung to this unrealistic stance and hopes of defeating both Sherman and Thomas’s powerful force in Tennessee:

I conceived the plan of marching into Tennessee … to move upon Thomas and Schofield and capture their army before it could reach Nashville and afterward march northeast, past the Cumberland River in that position I could threaten Cincinnati from Kentucky and Tennessee … if blessed with a victory (over Sherman coming north after him), to send reinforcements to Lee, in Virginia, or to march through gaps in the Cumberland Mountains and attack Grant in the rear.

It was whispered by not a few members of the Army of Tennessee that Hood was half mad from his injuries—a shot in the arm at Gettysburg and a leg shot off at Chickamauga shortly thereafter. Widely viewed as a gallant fighter, his leadership did not impress those under him in the sense that his tactics killed a lot of his men. Private Sam Watkins said, “As a soldier, he was brave, good, noble and gallant, and fought with the ferociousness of the wounded tiger, and with the everlasting grit of the bull-dog; but as a general he was a failure in every particular.”

Hood continued his march north, and Sherman, upon hearing the news, couldn’t have been happier, saying, “If he will go to the Ohio River, I will give him rations.” He sent Major General John M. Schofield’s Army of the Ohio, consisting of Major General David F. Stanley’s IV and Brigadier General Jacob B. Cox’s XXIII Corps, to Thomas to defend Tennessee and then turned his attention to his March to the Sea.

The Confederate Army of Tennessee reached Decatur, Alabama, on October 26, where Hood met General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard, commander of the Division of the West. Beauregard approved Hood’s plan to invade Tennessee but made him give up Wheeler’s cavalry, which was sorely needed in the coming campaign against Sherman in south Georgia. In exchange, Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Cavalry Corps was moving down from eastern Tennessee to provide coverage.

While waiting for Forrest to arrive, Hood moved his force west, retaking and fortifying Florence, Alabama, and Corinth, Mississippi, and repairing the railroad line between the cities to shuttle his supplies as needed. Forrest took nearly three weeks to arrive, finally appearing on November 17.

To counter Hood’s move west, Thomas sent Stanley’s corps, reinforced with one division from Cox’s corps, to Pulaski, Tennessee, directly astride the Nashville & Decatur Railroad that he expected Hood to advance on. On November 14 Schofield arrived in Pulaski to establish his headquarters and detail the defense against Hood’s army. At that time Schofield commanded an army of 25,000 infantrymen and 5,000 cavalry, while Thomas had another 40,000 troops scattered between Nashville and north Georgia, nearly all relatively fresh and well supplied. With Forrest’s arrival, Hood had about 33,000 infantrymen and 6,000 cavalrymen, all tired, battle-weary, and poorly supplied.

On November 19 Hood at long last moved out on his great campaign, led by Forrest’s cavalry and Lee’s corps. Rather than following the railroad as Schofield expected, Hood moved along three parallel roads to the west of the small town of Pulaski, heading toward Columbia, 31 miles to the north. The weather was wretched—a cold rain mixed with snow and sleet turning the muddy roads to ice, which cut and burned the bare feet of most of the tattered infantrymen.

Recognizing the danger of his flank being turned, Schofield hustled all but one brigade of his army to Columbia, arriving and fortifying the bridges over the Duck River by November 24. Hood’s army closed in on the town on the morning of November 26. That night he outlined yet another strategy to his three corps commanders. He told them that Nashville was an “open city” and a ripe prize to be easily taken. To do so, they had to move fast toward the capital city, bypassing what Union forces they could and overwhelming those they could not.

Once again, it is difficult to see just what Hood’s overall intent was. Originally moving north to draw Sherman out of Atlanta, he succeeded but then ran into Alabama rather than finding suitable terrain to fight from. Once in Alabama, he ignored Davis’s pleas not to abandon Georgia completely and convinced Beauregard that he could defeat Thomas’s forces in Tennessee piecemeal, recover the state for the Confederacy, then either help reinforce Robert E. Lee’s army in Virginia or invade Ohio. To do either he had to eliminate any Union threat from his own base of support by defeating Thomas, or at the very least by forcing him to retire from Tennessee. Yet, when literally given the opportunity to challenge parts of the Union Army with a superior force, at Pulaski and now at Columbia, he chose to outflank them and continue north.

One company of Hood’s army had arrived back home after nearly four years of combat—Captain A. M. Looney’s Company H of the 1st Tennessee Infantry Regiment, the “Maury County Grays.” One surviving original member, Private Sam Watkins, was overcome with emotion at what had happened to his friends and comrades:

The Maury Grays … left Columbia, four years ago, with 120 men. How many of these 120 original members are with the company today? Just twelve. Company H has twenty listed. But we twelve will stick to our colors till she goes down forever, and until five more of this number fall dead and bleeding on the battlefield.

Realizing early on that Hood had no intent of forming a direct assault at Columbia, and possibly was going to try to envelop him to the north, Schofield sent Stanley’s corps reinforced with additional infantrymen and artillery to the smaller city. The Union corps arrived at Spring Hill about 2 p.m.

Hood had sent Forrest to the north to bypass the Union defenses north of Columbia, and they arrived at Spring Hill at nearly the same time Stanley did. Both sides skirmished to no real gain on either side until just before dark. Lee’s corps had stayed outside Columbia to “make a racket” while Hood moved Cheatham’s and Stewart’s corps around to the east to Davis Ford on the Duck River, crossing through pastures, woods, and creeks before remerging on the Rally Hill (Franklin) Turnpike toward Spring Hill just at dark on November 29, neatly flanking Schofield in the maneuver.

Arriving just at dark, part of Cheatham’s corps came up and helped push the Union force back into town. Stanley managed to hold the town and keep the road to Columbia open. Hood’s army was exhausted by the rough marching and combat action, however, and nearly immediately lay down in the mud on either side of the road to catch some badly needed sleep.

As the Confederate infantry slept, Schofield slipped out of Columbia and passed through a mere 200-yard-wide gap between the two Southern corps without being detected, making it to Spring Hill without incident. When Hood found out, a huge fight between him and Cheatham erupted in which he blamed Cheatham for the escape and requested that Richmond send a replacement, while Cheatham complained he had not been specifically ordered to take and cut the road. While the rest of the Southern generals joined in the fun and argued through the night, Schofield and the rest of his corps moved out of Spring Hill and on toward Franklin, reaching the outer defenses by dawn on November 30. Once there, Schofield discovered he was not going to be able to move his men and heavy supply trains into the city until his engineers rebuilt the bridges and fords destroyed by Forrest’s raids. He ordered his men to hastily throw up earthwork defenses on the south edge of town in case Hood was following too closely. He planned on withdrawing back across the river after dark and then to move on up to Nashville during the night.

Hood was indeed following closely. After withdrawing his request for Cheatham’s replacement and making a few last rude comments, he got his army moving north again, chasing after Schofield. The vanguard of the Southern force arrived atop a low range of hills just south of Franklin just before 3 p.m., and Hood immediately gave orders to attack the Union lines they could clearly see being constructed. The three corps commanders were incredulous. Dusk was only a bit over two hours away, the army was still in a column formation with parts of it still hours away, and the Union troops clearly had a superior and fortified position well protected by artillery batteries.

This is when Hood threw another one of his fits. He had habitually considered anyone who disagreed with him an enemy and was loath to change any plan he had created, even in the face of overwhelming evidence that it was a poor one. In addition, he had often remarked since taking command that the men and officers loyal to former Army of Tennessee commander Johnston were “soft” and too prone to retreating in the face of the enemy. He insisted that they were to march right down there and take those works, even at the cost of their own lives, almost as a punishment for daring to disagree with him.

After 3 p.m., the two Confederate corps present started forming in lines of battle, Cheatham’s corps on the left, Stewart’s corps on the right. At the same time, the bridge and ford work had been completed, and Schofield was getting ready to pull his forces back north across the river. At 3:30 p.m. the signal trumpets blew, and a mass of butternut-clad infantry charged across the open ground toward the Union emplacements. Major General John Calvin Brown’s and Major General Patrick Ronayne Cleburne’s Confederate divisions briefly overran Brigadier General George B. Wagner’s division, which was left out on the road south of the main defense belt in an ill-thought-out move.

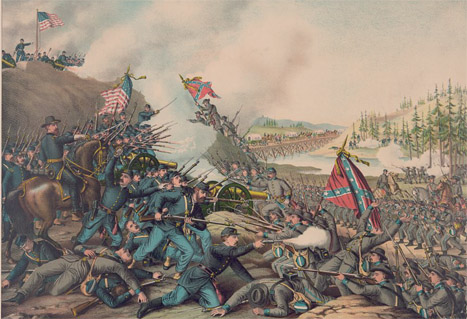

Battle of Franklin

Mounting a strong counterattack, Colonel Emerson Opdyke’s 1st Brigade (Wagner’s Division), which had been the rear guard all day and was taking a well-deserved rest at the river, leapt back over the defense wall and charged Cleburne’s men. A furious fight erupted with point-blank shots and hand-to-hand combat all along the line. One of his officers, Major Arthur MacArthur, father of the World War II hero Douglas MacArthur, managed to slash one Confederate regiment’s color bearer with his sword and take the prize, even though he was shot three times in the process.

All along the rest of the line, individual regiments and brigades reached the second Union line of defense, but none was able to pierce it. The field behind them now raked by constant canister and shot from the Union batteries, there was no place left to retreat either. Both sides stood just yards apart for hours, pouring musket and artillery fire into each other’s ranks, without either side giving way.

The slaughter finally stopped about 9 p.m., well after dark, when gun by gun, the firing slowly petered out. Surviving Confederate regiments literally crawled back across the dead-strewn field to the safety of their original positions. Schofield promptly abandoned the field, leaving his dead and wounded behind, and immediately marched back to Nashville, arriving about noon on December 1.

Hood’s casualties were almost unfathomable. Of the 26,000 he had sent into battle, 5,550 were dead or wounded, with another 702 missing. Thirty-two regimental and brigade battle flags had been taken. No less than 54 regimental commanders were killed, wounded, or missing. The worst loss was that of six generals: Cleburne, Brigadier General John Adams, Brigadier General Otho French Strahl, Brigadier General States Rights Gist, Brigadier General John Carpenter Carter, and Brigadier General Hiram Bronson Granbury. Of the other six generals on the battlefield, one had been captured and only two were left unwounded and fit for service.

Schofield’s casualties, although heavy, were still lighter than Hood’s. Of the 28,000 men Schofield had on the line that afternoon, 1,222 were killed or wounded, while 1,104 were captured or missing.

Hood’s army was in no shape to fight after the beating at Franklin, but nothing would deter Hood from his determination to take the Tennessee capital back. Schofield’s forces had quit the field at Franklin immediately after the battle, and Hood followed suit. Ordering his men up and at ’em, the depleted Confederate Army of Tennessee stood outside the defenses of Nashville by December 2.

Once again, we face the question of what Hood was planning to do. He admitted himself after the war that he knew his army was too depleted to assault the Nashville emplacements and that Schofield was well placed and well supplied and had reinforcements on the way. By no stretch of the imagination could one follow or endorse his plan (as outlined in his postwar memoirs, Advance and Retreat): wait outside for Thomas’s combined army to come out and attack his own fortifications and hope that promised reinforcements (which probably did not even exist) of his own could manage to travel from Texas in time to help him.

Thomas, on the other hand, was quite comfortable and in no mood to hurry into a fight. Major General Andrew Jackson Smith arrived with his three divisions of XVI Corps by the time Schofield came in from Franklin, and Major General James Blair Steedman brought up a division of 5,200 men detached from Sherman’s command the next day. By December 4, Thomas had a total of 49,773 men under his command, some of whom were well rested and had not seen combat recently, while Hood could muster (on paper) only 23,207 tired, cold, and demoralized troops. This figure did not take into consideration the large number of desertions of battle-hardened veterans the South’s Army of Tennessee was beginning to experience.

Under growing pressure from Grant to go into action, Thomas made preparations to decisively defeat the weaker Confederate Army and gain “such a splendid and decisive victory as to hush censure for all time.” Finally, at 6 a.m. on the foggy morning of December 15, his army moved out. Thomas planned to hit both of Hood’s flanks with a coordinating attack that would destroy his lines of battle in a matter of minutes. Thomas had no desire to simply push Hood away from Nashville; he was determined to destroy that Confederate army once and for all.

Steedman started the attack at 8 a.m. on Hood’s right, the coordinated plan falling apart immediately due to the poor weather and bad roads. Two hours later Smith’s corps hit Hood’s left flank, followed by Wood and Schofield over the next few hours. Hood was steadily pushed back, but his lines held fast and pulled together to form a tight, straight line of battle. By nightfall, Hood had been pushed back about a mile, where he formed a new line of battle that stretched between Shy’s Hill and Overton Hill.

At dawn on December 17, Thomas’s forces started probing the new Confederate line for weakness. At 3 p.m. a strong attack was made against the defense atop Overton Hill, followed a half-hour later by initial actions against Shy’s Hill. By 4 p.m. the attack on Hood’s right had been repulsed with heavy losses, but the attack on Shy’s Hill succeeded in routing the Confederate defenders and effectively bringing the battle to an end.

Hood’s army photographed during the Battle of Nashville

The Confederate Army of Tennessee was at long last broken. All semblance of order broke down as many soldiers either ran for the rear or allowed themselves to be taken prisoner. Many more simply dropped their rifles and returned home, too defeated to fight anymore. Hood pulled what was left south out of Nashville and marched through a brutal winter landscape all the way back down to Tupelo, Mississippi. Once there, Hood quietly asked to be relieved of command on Friday, January 13, 1865.

Hood insisted that his losses were “very small,” but he was not the sort to admit defeat or desertion of his own men. Various sources give wildly disparate figures, but a rough guess is that Hood lost about 1,500 killed and wounded in the battle, with another 4,500 captured. He lost a grand total of nearly 20,000 men in the whole failed campaign. Thomas reported losses of 387 killed, 2,562 wounded, and 112 missing in the battle.

Even after this shattering defeat, the end of this great army was not yet at hand. Reorganizing yet again, the Army of Tennessee was reunited with its beloved commander, General Joseph Eggleston Johnston, and moved back east to confront Sherman once again, this time in his march through the Carolinas.

Belle Meade Plantation

5025 Harding Pike

Nashville, TN

(615) 356-0501

www.bellemeadeplantation.com

Relive a bit of the Old South at Belle Meade Plantation, the 1853 mansion known as the “Queen of the Tennessee Plantations.” The Greek Revival mansion was once the centerpiece of a 5,400-acre plantation known the world over in the 19th century as a thoroughbred farm and nursery. In 1807 John Harding purchased a log cabin and 250 acres of land adjacent to the Natchez Trace from the family of Daniel Dunham. Harding and his wife, Susannah, enlarged the cabin as their family grew. In the 1820s they began construction of the present-day Belle Meade (a French term meaning “beautiful meadow”) mansion, originally a two-story, Federal-style farmhouse.

Harding, who built a successful business boarding and breeding horses, continued to add to his estate. In 1836 his son, William Giles Harding, established the Belle Meade Thoroughbred Stud. William Giles Harding made additions to the mansion in the 1840s and in 1853. The Hardings also maintained a wild deer park on the property and sold ponies, Alderney cattle, Cotswold sheep, and cashmere goats. During the Civil War, the Federal government took the horses for the army’s use and removed the plantation’s stone fences. Loyal slaves are said to have hidden the most prized thoroughbreds. The mansion was riddled with bullets during the Battle of Nashville.

After the war, William Giles Harding and his son-in-law, William H. Jackson, expanded the farm. It enjoyed international prominence until 1904, when the land and horses were auctioned. The financial crisis of 1893, an excessive lifestyle, and the mishandling of family funds led to the downfall of Belle Meade, which in the early 1900s was the oldest and largest thoroughbred farm in America. The stables housed many great horses, including Iroquois, winner of the English Derby in 1881. The mansion and 24 remaining acres were opened to the public in 1953 under the management of the Nashville Chapter of the Association for the Preservation of Tennessee Antiquities. For more information on Belle Meade, read Belle Meade: Mansion, Plantation and Stud by Ridley Wills III (1991: Vanderbilt University Press, Nashville). Wills is the great-great-grandson of William Giles Harding and the great-grandson of Judge Howell E. Jackson.

The beautifully restored mansion is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. It is elegantly furnished with 19th-century antiques and art of the period. The site also includes the 1890 carriage house and stable filled with antique carriages; the 1790 log cabin (one of the oldest log structures in the state); and six other original outbuildings, such as the garden house, smokehouse, and mausoleum. Guides in period dress lead tours of the property, offering a look back at the lifestyles of early Nashville’s rich and famous. The shaded lawn is a popular site for festivals. The last tour starts daily at 4 p.m.

Carnton Plantation

1345 Carnton Lane

Franklin, TN

(615) 794-0903

www.carnton.org

This 1826 antebellum plantation was built by Randal McGavock, who was Nashville’s mayor in 1824 and 1825. The late-neoclassical plantation house is considered architecturally and historically one of the most important buildings in the area. In its early years, the mansion was a social and political center. Among the prominent visitors attending the many social events there were Andrew Jackson, Sam Houston, and James K. Polk.

On November 30, 1864, after the bloody Battle of Franklin, the home was used as a hospital. Wounded and dead soldiers filled the house and yard. The Confederates lost 10 generals during the battle to death, injury, or capture. The bodies of five of the generals were laid out on the mansion’s back porch. At that time, Carnton was the home of McGavock’s son, Colonel John McGavock, and his wife, Carrie Winder McGavock. In 1866 the McGavock family donated two acres adjacent to their family cemetery for the burial of some 1,500 Southern soldiers. The McGavock Confederate Cemetery is the country’s largest private Confederate cemetery.

Carter House

1140 Columbia Ave.

Franklin, TN

(615) 791-1861

www.carterhouse1864.com

This 1830 brick house was the center of fighting in the Battle of Franklin in 1864, one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War. The house, built by Fountain Branch Carter, was used as a Federal command post while the Carter family, friends, and neighbors hid in the cellar during the battle. Among the dead in the battle was Captain Tod Carter, the youngest son of the Carter family, who fought for the South and died at the home 48 hours after being wounded.

The Carter House is a registered National Historic Landmark. A video presentation, access to the visitor center museum featuring Confederate artifacts and photos of soldiers, and a guided tour of the house and grounds are included with admission to the attraction. Hours vary by season.

Oaklands Historic House Museum

900 N. Maney Ave.

Murfreesboro, TN

(615) 893-0022

www.oaklandsmuseum.org

One of the most elegant antebellum homes in Middle Tennessee, this house began around 1815 as a one-story brick home built by the Maney family. The family enlarged the house with a Federal-style addition in the early 1820s and made more changes in the 1830s. The last addition was the ornate Italianate facade, completed in the 1850s.

Oaklands was the center of a 1,500-acre plantation. Union and Confederate armies alternately occupied the house during the Civil War. On July 13, 1862, Confederate brigadier general Nathan Bedford Forrest led a raid here, surprising the Union commander at Oaklands. The surrender was negotiated here. In December 1862 President Jefferson Davis of the Confederacy boarded at Oaklands while visiting nearby troops. There is a gift shop on the property.

Sam Davis Home Historic Site

1399 Sam Davis Rd.

Smyrna, TN

(615) 459-2341

www.samdavishome.org

This Greek Revival home, built around 1820 and enlarged around 1850, sits on 169 acres of the original 1,000-acre farm that was the home of Sam Davis. Davis, called the “Boy Hero of the Confederacy,” enlisted in the Confederate Army at the age of 19. He served as a courier, and while transporting secret papers to General Braxton Bragg in Chattanooga, he was captured by Union forces, tried as a spy, and sentenced to hang. The trial officer was so impressed with Davis’s honesty and sense of honor that he offered him freedom if he would reveal the source of military information he was caught carrying. Davis is reported to have responded, “If I had a thousand lives I would give them all gladly rather than betray a friend.” He was hanged in Pulaski, Tennessee, on November 27, 1863. The home is a typical upper-middle-class farmhouse of the period. A tour of the property also includes outbuildings. Several annual events take place here. Hours vary by season.

Stones River National Battlefield

3501 Old Nashville Hwy.

Murfreesboro, TN

(615) 478-1035

www.nps.gov/stri

One of the bloodier Civil War battles took place at this site between December 31, 1862, and January 2, 1863. More than 83,000 men fought in the battle; nearly 28,000 were killed or wounded. Both the Union Army, led by Major General William S. Rosecrans, and the Confederate Army, led by General Braxton Bragg, claimed victory. However, on January 3, 1863, Bragg retreated 40 miles to Tullahoma, Tennessee, and Rosecrans took control of Murfreesboro.

The Union constructed a huge supply base within Fortress Rosecrans, the largest enclosed earthen fortification built during the war. The battlefield today appears much as it did during the Battle of Stones River. Most of the points of interest can be reached on the self-guided auto tour. Numbered markers identify the stops, and short trails and exhibits explain the events at each site. Plan to spend at least two hours to get the most out of your visit, and stop first at the visitor center. An audiovisual program and museum will introduce you to the battle. A captioned slide show is available, too. Pick up a brochure guide or recorded guide to use on the self-guided auto tour.

During summer, artillery and infantry demonstrations and talks about the battle are scheduled. The park is administered by the National Park Service. Admission is free. (See the Other Tennessee Battlefields chapter for a complete description of this battle.)

Tennessee State Capitol

Charlotte Ave. between Sixth and Seventh Aves.

Nashville, TN

(615) 741-0830

www.tnmuseum.org

The Greek Revival–style building was begun in 1859. Its architect, William Strickland of Philadelphia, began his career as an apprentice to Benjamin Latrobe, architect of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. Strickland died before the Tennessee State Capitol was completed and, per his wishes, was buried in the northeast wall of the building, near the north entrance. Strickland’s son, Francis Strickland, supervised construction until 1857, when Englishman Harvey Akeroyd designed the state library, the final portion of the building.

The capitol stands 170 feet above the highest hill in downtown Nashville. On the eastern slope of the grounds is the tomb of President and Mrs. James K. Polk and a bronze equestrian statue of President Andrew Jackson. During the Civil War the capitol was used as a Union fortress. In the 1930s the murals in the governor’s office were added. Various restoration projects have taken place over the years. In 1996 a bronze statue of Andrew Johnson was erected so that all three U.S. presidents from Tennessee are commemorated on the capitol grounds.

Guided tours are conducted and a brochure is available for self-guided tours. Admission is free.

As a major metropolitan area and convention destination, Nashville and the surrounding area are filled with chain motels and hotels, mostly clustered near the airport and around the interstate highway exits.

| The Old Marshall House Bed and Breakfast | $$–$$$ |

1030 John Williams Rd.

Franklin, TN

(615) 791-1455

This two-story farmhouse was built in 1867 by Joseph Kennedy Marshall, who was released in 1865 after 16 months as a Confederate prisoner in Rock Island Prison. The home is now a bed-and-breakfast, with rooms in the main house as well as the on-site log cabin (The Cat’s Meow) that served as the original owner’s home during the building process. The house is located near Carter House and Carnton Plantation.

| F. Scott’s Restaurant and Jazz Bar | $$–$$$ |

2210 Crestmoor Rd.

Nashville, TN

(615) 269-5861

Casually elegant, warm, and inviting, F. Scott’s is considered by many to be one of the best restaurants in Nashville. This is a place where the sophisticated feel comfortable, but it’s not necessary to dress up to the hilt; you’ll fit in, whether you’re in jeans or coat and tie. F. Scott’s serves American bistro-style food. The menu changes seasonally, but there is always plenty of pasta, chicken, duck, lamb, pork, and fresh fish. F. Scott’s has three dining rooms and a jazz bar with live entertainment six nights a week. In addition to a wonderful dining experience, this is a very pleasant place to stop for a drink. F. Scott’s is open only for dinner, and reservations are recommended.

| Hog Heaven | $ |

115 27th Ave. N.

Nashville, TN

(615) 329-1234

This is a good time to apply the “don’t judge a book by its cover” rule. Hog Heaven doesn’t look like much—it’s a tiny white cinder-block building tucked in a corner of Centennial Park behind McDonald’s—but once you taste their barbecue, you’ll know why they attached the word “heaven” to the name. This is some good eatin’. Hog Heaven’s hand-pulled pork, chicken, beef, and turkey barbecue is actually pretty famous among Nashville’s barbecue connoisseurs.

The menu is posted on a board beside the walk-up window. After you get your order, you might want to hop on over to Centennial Park and dig in, since the only seating at the restaurant is two picnic tables on a slab of concrete right in front of the window. You can order barbecue sandwiches, barbecue plates that come with two side orders, and barbecue by the pound. The white barbecue sauce is just right on top of the chicken, and the regular sauce comes in mild, hot, or extra hot. Quarter-chicken and half-chicken orders are available, and Hog Heaven has spareribs, too. Barbecue beans, potato salad, coleslaw, turnip greens, white beans, green beans, and black-eyed peas are among the side dishes. The homemade cobbler is a heavenly way to end a memorable Hog Heaven meal. Hog Heaven delivers to areas nearby.

| Sunset Grill | $$–$$$ |

2001-A Belcourt Ave.

Nashville, TN

(615) 386-3663

Sunset Grill is one of Nashville’s favorite restaurants. It serves new American cuisine in a casually elegant atmosphere. Any night of the week you’re apt to see customers in jeans dining next to a group in tuxedos.

The Voodoo Pasta is a menu staple. It has grilled chicken, bay shrimp, and andouille sausage in spicy Black Magic tomato sauce with fresh egg fettucini pasta. The Vegetarian Voodoo Pasta has eggplant, spinach, and mushrooms, in a spicy Black Magic tomato sauce with egg fettuccini pasta. Other menu favorites include blackberry duck and lamb dijonnaise. There is a good selection of vegetarian dishes. The desserts are beautiful and extensive in choice, but don’t worry, you can also order a large dessert trio or half-portions. If you want to go all out, order the dessert mirror, 10 full portions of various desserts served on a mirrored tray.

Sunset Grill has an excellent wine selection—one of the best in town—with more than 200 wines, 60 available by the glass. The Tuesday-afternoon wine-tasting classes have become quite popular; seating is limited for these, so make a reservation if you don’t want to miss out. Sunset Grill is one of the few places in town that has a late-night menu.