Chattanooga: The Battle above the Clouds

In the late afternoon of September 20, 1863, following the disaster at Chickamauga (see chapter on Chickamauga), Union troops streamed back in a near panic to their stronghold at Chattanooga. Many abandoned both arms and equipment in their haste to escape the Confederate force they thought would surely pounce at any moment. Amid them (and in front of a great number of them) rode their dispirited commander, Major General William Starke Rosecrans, no doubt wondering how to tell his bosses that earlier dispatches predicting victory in the north Georgia battle were premature at best.

Although his able lieutenant, Major General George Henry Thomas, the “Rock of Chickamauga,” still held his ground at the northern end of the battleground, Rosecrans was in near hysterics on hearing (untrue) rumors that 20,000 or more Confederate troops under Lieutenant General Richard S. Ewell were on their way from Virginia. In quick succession, Rosecrans telegraphed Washington begging for “all reinforcements you can send hurried up,” and he sent other telegrams stating he could stand and fight and others that claimed he would soon have to withdraw north. To complete his rushed and distracted set of actions, he ordered Thomas to retreat and join him in Chattanooga, and that small outposts atop Lookout Mountain be abandoned as “undefensible.”

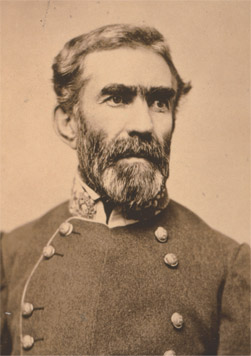

Major General George Henry Thomas, known as the “Rock of Chickamauga”

Chattanooga had first fallen into Union hands in early September 1863, the Confederate force under General Braxton Bragg pulling out without a shot being fired when Rosecrans’s three columns—including 60,000 men moving south—threatened to cut the rail line to Atlanta. At the same time, Major General Ambrose Burnside’s Union Army of the Ohio, divided into four columns including 24,000 men, swept down on the smaller Confederate garrison at Knoxville, also forcing it to abandon the city without a fight. The two Confederate forces combined under Bragg in northwest Georgia, just below the Tennessee line. For all practical purposes, Tennessee was then under complete Union control.

Strangely enough, at this time both forces were closely matched in both troop strength (56,359 Union to 65,165 Confederate) and the controversial nature of their sometimes simply incompetent commanders. Bragg was intensely despised by both officers and ordinary soldiers and kept his rank and position primarily by way of his personal friendship with President Jefferson Davis. Private Sam Watkins of the Maury Grays, 1st Tennessee Infantry, said, “None of General Bragg’s soldiers ever loved him. They had no faith in his ability as a general. He was looked upon as a merciless tyrant.”

Bragg also was noted for his personal vendettas against his “enemies,” those fellow Confederate officers who disagreed with him on one point or another. In the midst of renewed Union offenses in the summer of 1863, Bragg chose instead to pay more attention to his conspiracies against outstanding generals such as major generals Benjamin Frank Cheatham and John McCowan and Lieutenant General William J. Hardee.

General Braxton Bragg

Rosecrans, on the other hand, was considered a dangerous tactician by his Confederate foes, but while loved by his men and admired for his generalship in most battles, his own peers thought him unstable and prone to panic under stress. Lincoln later remarked that Rosecrans had acted “confused and stunned like a duck hit on the head.” In the midst of Rosecrans’s rushed preparations for the retreat to Chattanooga, one glaring problem escaped his notice—his own supply lines. Confederate forces had cut his northern rail access, steep and nearly impassable mountains surrounded him on three sides and were soon to be manned with Confederate artillery and infantry emplacements, and a low-water situation combined with adjacent Confederate outposts on the Tennessee River flowing past his command prevented resupply by riverboat. To add to his woes, most of a more than 800-hundred-wagon supply train coming in on the one inadequate road was captured on October 2 by Major General Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry raiders. Rations at this point were estimated at a mere 10 days’ worth, and ammunition existed for only about two days of fully involved combat. Instead of a fortified redoubt, Rosecrans’s muddled planning had placed them in an isolated prison.

Tell old Bragg for God’s sake not to let the Yanks whip him as he usually does when this army gains a victory … If the armies of the West were worth a goober we could soon have piece [sic] on our own terms.

—Private W. C. McClellan of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, in a letter to his father in northern Alabama, as quoted in Bell Irvin

Wiley’s Life of Johnny Reb

On the Confederate side, things were hardly better. At Chickamauga, to the outrage of his senior commanders, Bragg refused to allow them to press on after the rapidly retreating routed majority of Union forces, ordering instead a concentration of effort on Thomas’s sparse force holding fast to Horseshoe Ridge. Even after Thomas’s men slipped away after nightfall on September 20, Bragg refused to allow a pursuit, believing the noises the retreating Union forces were making indicated they were preparing for an assault the next morning. Not until two full days later did Bragg move forward to Missionary Ridge, only to see the Union forces already well entrenched within Chattanooga below.

After some patrol and light skirmishing action on September 22 showed the extent of the Union Army’s fortifications, Bragg settled down to try to starve out the besieged city garrison. Within a few days, Union rations were reduced by half, then to one-quarter. Even with some supplies coming in through a torturous 65-mile mountain route constantly under attack by Wheeler’s cavalry, it became nearly impossible to maintain even this inadequate ration. Guards were posted to prevent soldiers from stealing the feed of the most essential horses; another 15,000 horses and mules simply died of starvation.

After heavy rains washed out the only bridge on their own supply line, Confederate men were reduced to the same meager rations as their Union foe. With the infantry obviously dissatisfied with Bragg’s tactics and personal vendettas, as well as the bleak supply situation, President Davis decided to make a mid-October visit to the battlefield to shore up morale. It didn’t work as planned, as Sam Watkins describes:

And in the very acme of our privations and hunger, when the army was most dissatisfied and unhappy, we were ordered into line of battle to be reviewed by Honorable Jefferson Davis. When he passed by us, with his great retinue of staff officers and play-outs at full gallop, cheers greeted them, with the words, “Send us something to eat, Massa Jeff. Give us something to eat, Massa Jeff. I’m hungry! I’m hungry!”

Battle of Chattanooga

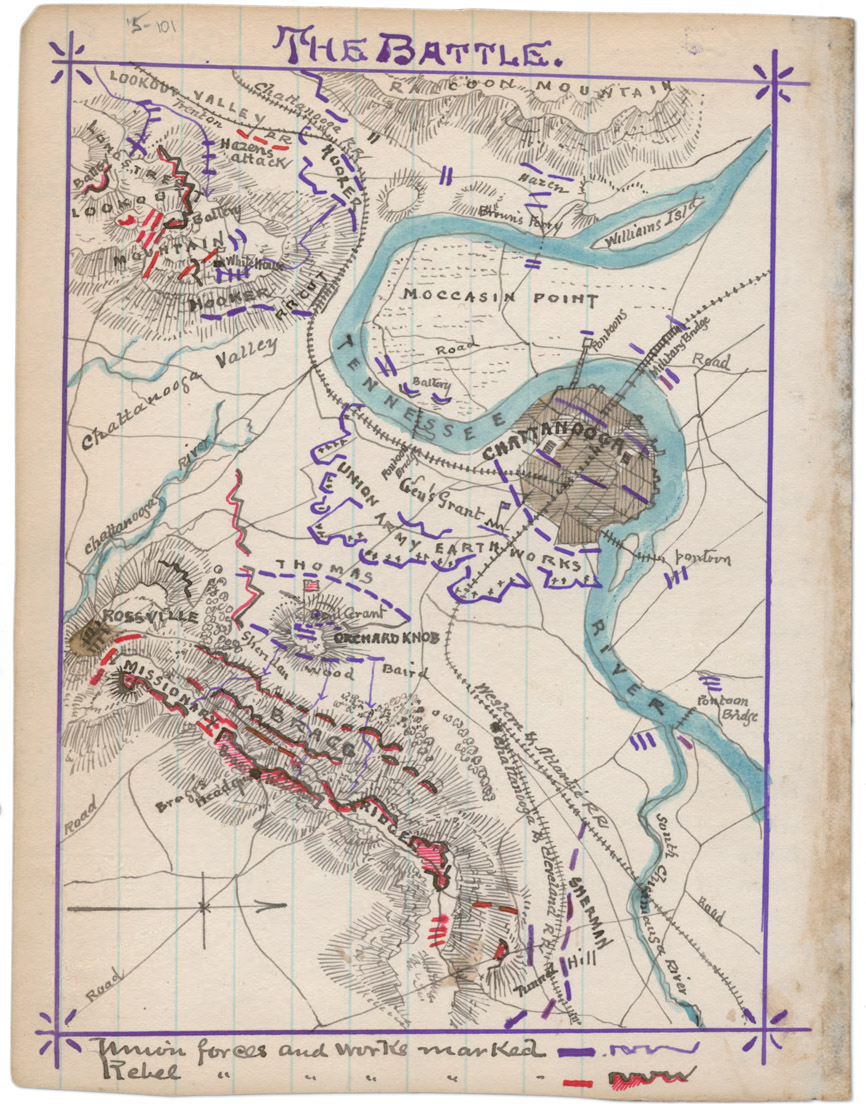

Unknown to either side at Chattanooga, at least at first, once word of the situation reached Washington, four divisions of General William T. Sherman’s Army of Tennessee set out from Vicksburg and two corps under Major General Joseph Hooker set out from Virginia. On October 30 the forward elements of Hooker’s corps reached Bridgeport, Tennessee, and Rosecrans made plans to assault and seize the closest ferry point, Brown’s Ferry, just west of Lookout Mountain itself. Before all could be made ready, Rosecrans was relieved of command and replaced by Thomas. Major General U. S. Grant himself arrived with reinforcements from Vicksburg on October 23, and both commanders agreed to continue with Rosecrans’s plans.

Lookout Mountain

Led by Lieutenant Colonel James C. Foy of the 23rd Kentucky Infantry, hastily gathered pontoons and other flatboats floated quietly downriver on the night of October 27 and captured Brown’s Ferry with hardly a shot being fired by the small Confederate outpost. While engineers and pioneers hastily assembled a pontoon bridge to bring reinforcements across, Foy had his men entrench for the attack that was sure to come.

The only Confederate troops nearby did soon mount an attack, but only about one-half of a regiment under Colonel William C. Oates could be summoned for the assault. In a 20-minute fight, Oates’s men were routed by both Foy’s men and other Union units hastily brought across the still-unfinished bridge. The key to Bragg’s entire strategy—Brown’s Ferry—had been guarded by a tiny, unsupported percentage of the men under his command.

On October 28, with Bragg and Lieutenant General James Longstreet personally observing from atop Lookout Mountain, Brigadier General John West Geary’s 2nd Division of Hooker’s 12th Corps crossed the newly finished pontoon bridge and entered Lookout Valley, stopping at the Wauhatchie rail junction. At midnight that same night, Brigadier General Micah Jenkins’s Division of Longstreet’s corps attacked Geary, now reinforced by two other brigades. The three-hour fight resulted in both Jenkins’s being thrown back and a complete Confederate withdrawal out of the valley and up onto the slopes of Lookout Mountain, leaving all the good supply lines into the city in Union hands. The Confederates still held all the high ground surrounding the city, and Bragg remained confident that this was the only advantage he would really need.

With the Union situation improving by the day with fresh men and supplies coming in, and the Confederate supply problems mounting, Bragg amazingly decided to concentrate on his own personal vendettas once again. Blaming Longstreet for the Union successes at Brown’s Ferry and Wauhatchie, Bragg ordered him and two other generals to prepare for an all-out assault on the strong Union positions in Lookout Valley. Longstreet duly reported for the three of them that such an attack would be “impracticable.”

Viewing this sensible report as a personal affront, Bragg decided Longstreet’s attitude was unacceptable. In a letter to Jefferson Davis, Bragg complained that Longstreet was “disrespectful and insubordinate” and reported that he planned to send him off with his corps to the renewed campaign around Knoxville. On November 4, Longstreet left by rail with nearly a third of Bragg’s entire force.

Sherman’s forces finally began arriving on November 21, and with this encouraging news, Grant ordered attacks to begin as soon as possible. His first target was a small, steep hill in front of Missionary Ridge called Orchard Knob. On the morning of November 23, three Union brigades led by brigadier generals William B. Hazen, August Willich, and Samuel Beatty stormed the lightly held outpost, capturing the knob in about five minutes of heavy fighting. The surviving Confederates fled back to the entrenchments at the base of Missionary Ridge, and almost before they knew it, the Union held one of the best strategic observation posts for the coming battle. The cost was very high, though, with Hazen alone losing 167 men.

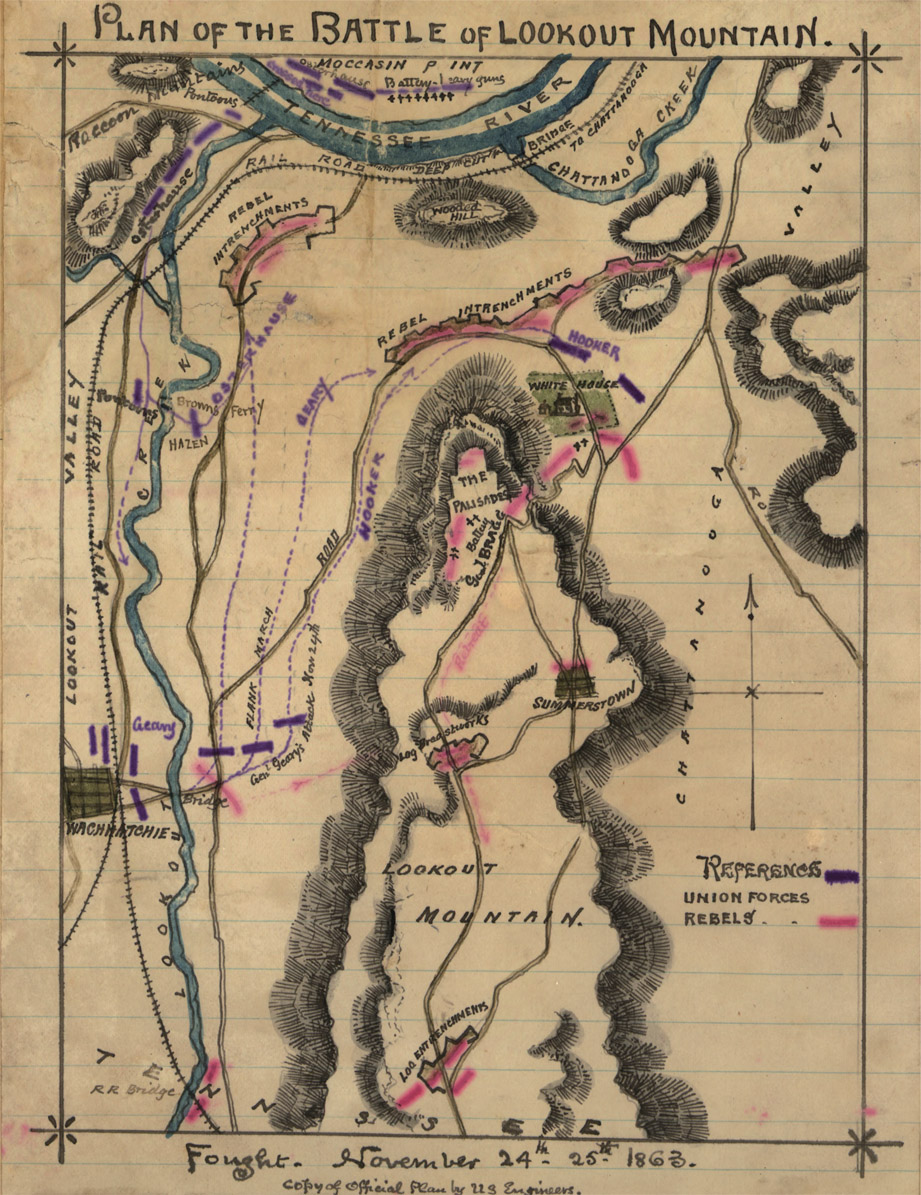

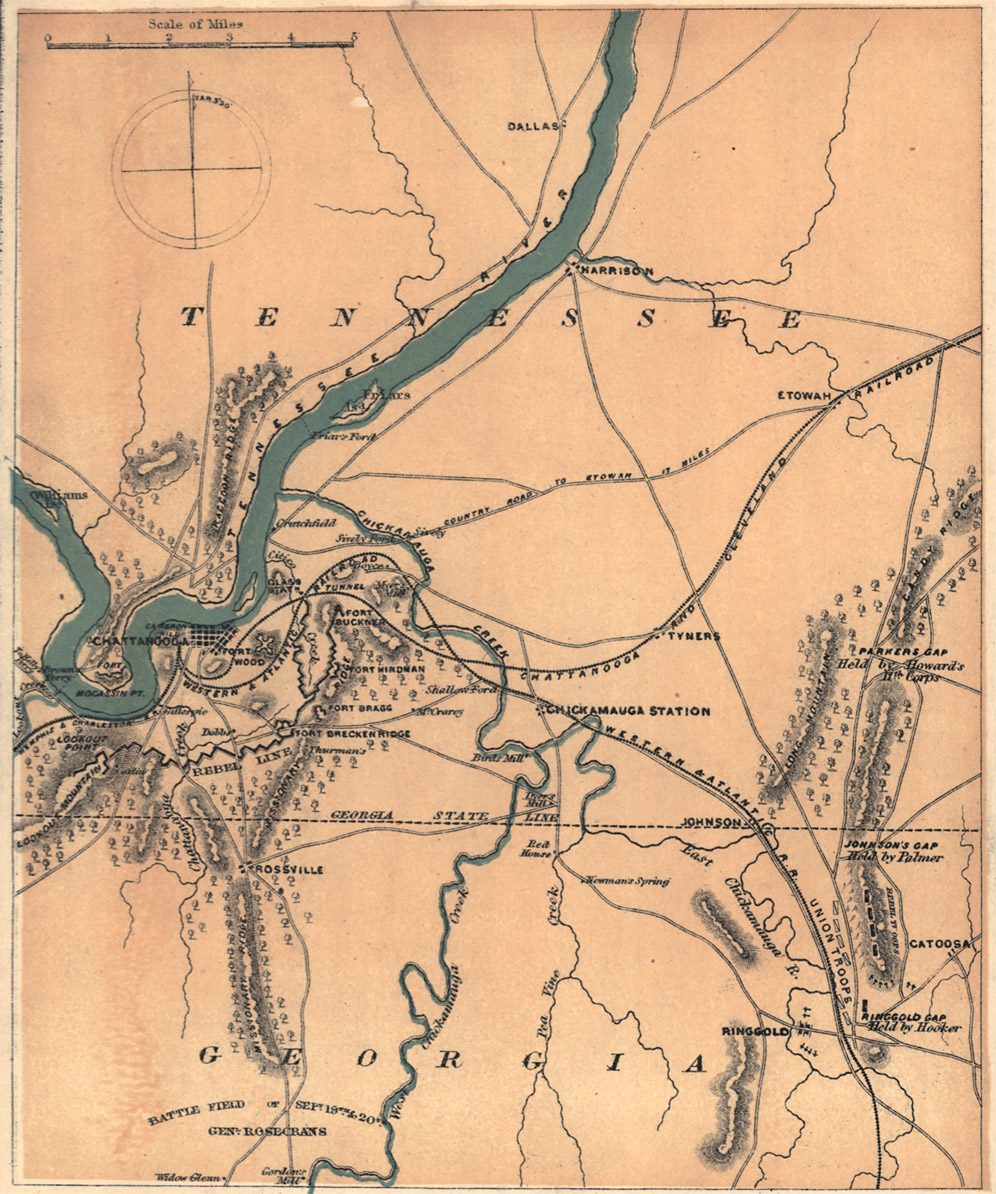

Map of the Battle of Lookout Mountain

Early the next morning, with Sherman’s forces fully across the river (but mistakenly out of position to strike at Missionary Ridge), Hooker was ordered to make a “demonstration” against Lookout Mountain, to draw attention away from the main assault on Missionary Ridge. With a low fog enveloping the mountain and obscuring the view of Confederate artillery and infantry outposts atop the mountain at Point Lookout, Geary’s division supported by Brigadier General Walter C. Whitaker’s brigade moved quietly up the flank of the rough, boulder-encrusted mountainside, aiming not to take the upper crest (which Hooker thought was completely immune to direct assault) but to capture the middle and lower reaches of the mountainside. When they at last encountered a line of Confederate entrenchments and emplacements manned by Brigadier General Edward C. Walthall’s brigade, they found to their joy that the Confederate force was positioned to repulse a direct assault up the slope, not from across the steep mountainside. In less than 15 minutes of furious fighting, the Confederate force was driven out and sent fleeing back to its main line of defense at the Cravens House.

The Cravens House

Storming around the mountain after the fleeing Confederates, the Union forces, led now by the 60th and 137th New York Regiments, advanced through a furious cannonade toward the white farmhouse, close behind Walthall’s retreating Confederates. They closed in so tight that a two-gun battery at the Cravens House itself was unable to fire upon them, for fear of hitting its own troops, and the house was soon overrun and captured. More Confederate forces arrive to shore up the trench lines of the tiny battleground, but they were soon routed and sent fleeing down the mountain by Whitaker’s reserve brigades coming onto the field.

Geary sent word to Hooker of their achievement and asked for resupply so that they could advance farther. Amazed and almost upset that this “demonstration” had gone so far, Hooker ordered Geary and Whitaker to entrench and stay put. With the Confederate forces above and around them in the woods keeping up a steady fire and even rolling large boulders down the mountainside at them, the Union forces manned their enemies’ previous breastworks and waited.

Bragg, alerted to his plight on Lookout Mountain by the sound of heavy Union artillery being placed atop it, made a fatal decision. Convinced that this action constituted a major assault on his commanding position, he ordered the withdrawal of all units from atop and on Lookout Mountain, and the valley below as well, to concentrate his forces on Missionary Ridge. By sunrise on November 25, Hooker had complete command of the entire mountain, at least by default. As a final act, men of the North’s 8th Kentucky and 96th Illinois Infantry Regiments climbed the nearly sheer rocky cliffs to plant their flags on the abandoned emplacements.

The oft-remarked “battle above the clouds” in fact never really occurred; at best, it could be accurately called the “battle within the fog.” Grant himself grumbled over the brief fight’s wide exposure and exaltation in the press, stating that it had hardly even constituted a skirmish. In his postwar memoirs he remarked, “The Battle of Lookout Mountain is one of the romances of the war. There was no such battle and no action even worthy to be called a battle on Lookout Mountain. It is all poetry.”

With reinforcements from the withdrawn positions around Chattanooga coming in line, Bragg had a strong position on Missionary Ridge. Aside from the natural defense of the steep mountain terrain, he had positioned his men in two main defensive bands. The first line of defense was a set of interlocking rifle pits at the mountain’s base and the second was a set of strongly reinforced breastworks nearly atop the ridgeline, reinforced by artillery emplacements.

Turning attention immediately toward his main objective, Grant ordered Sherman to attack the far right of the Confederate line on Missionary Ridge early on the morning of November 25. Moving forward on the afternoon of the 24th, Sherman discovered too late that the hill his men were already assaulting, Billy Goat Hill, was not continuous with the ridgeline but separated by a steep and wooded ravine. With his typical bullheadedness, Sherman attempted to push through the ravine and hit the far right of the Confederate line anyhow, only to be halted by Major General Patrick R. Cleburne’s still entrenching troops. Even with a near seven-to-one advantage, the Union forces could not push through the strong Confederate position. Even worse, a counterattacking downhill bayonet charge by Cleburne’s men at a part of the ridge called Tunnel Hill pushed the Union line back to the base of the hill and captured nearly a whole Union brigade’s worth of men after an incredibly fierce hand-to-hand fight.

With Sherman stuck on the Union left, Grant ordered Hooker to cross the valley and strike on the low ridges on the right, with Thomas’s men, to make a “demonstration” from Orchard Knob toward the middle of the Confederate line. As planned, this center attack would force the Confederates to shift their men away from the flanks, giving Sherman and Hooker the edge they needed to take the flanks.

Once more, the “demonstration” became the battle centerpiece. About 3:30 p.m., Thomas’s men moved forward with orders to engage the first set of rifle pits and halt. Charging across the nearly half-mile of open ground, under inaccurate and ineffective Confederate artillery fire all the while, the Union troops quickly took over the Confederate rifle pits, earlier ordered to be abandoned when attacked in a serious tactical blunder by Lieutenant General William J. Hardee. Under heavy and accurate fire from above, Thomas’s men realized that to stay in this exposed position was sheer suicide. Ignoring his orders, Lieutenant Colonel William P. Chandler of the 35th Illinois Infantry leapt to the top of the breastwork and, with a cry of “Forward!,” led his men up the steep hillside.

This was all the motivation that the rest of Thomas’s command needed, and company by company, roaring at the top of their lungs, soon all were in full assault uphill. Atop Orchard Knob, Grant was horrified at the sight. With the memory of Sherman’s men in full flight down Tunnel Hill still very fresh, he had a terrible vision of Thomas’s men being chewed to pieces and routed. Turning in anger, he demanded of his corps commanders who had ordered that charge. Thomas and Major General Gordon Granger both calmly answered, truthfully, that they had not. Grant turned back to watch the scene unfolding, muttering that if that attack failed, someone would pay dearly. One does get the impression that he was not referring to the infantrymen.

Sweeping like a wildfire up the mountainside, the uncoordinated attacks all along the center of the Confederate lines could not be stopped. About 5 p.m., the 32nd Indiana and 6th Ohio Infantry Regiments reached the crest at Sharp’s Spur, right in the center of Colonel William F. Tucker’s Mississippi Brigade. Quickly capturing one 12-pounder Napoleon of Captain James Garrity’s Alabama Battery, the Ohio men forced the Confederate gunners at bayonet point to fire on their own retreating men.

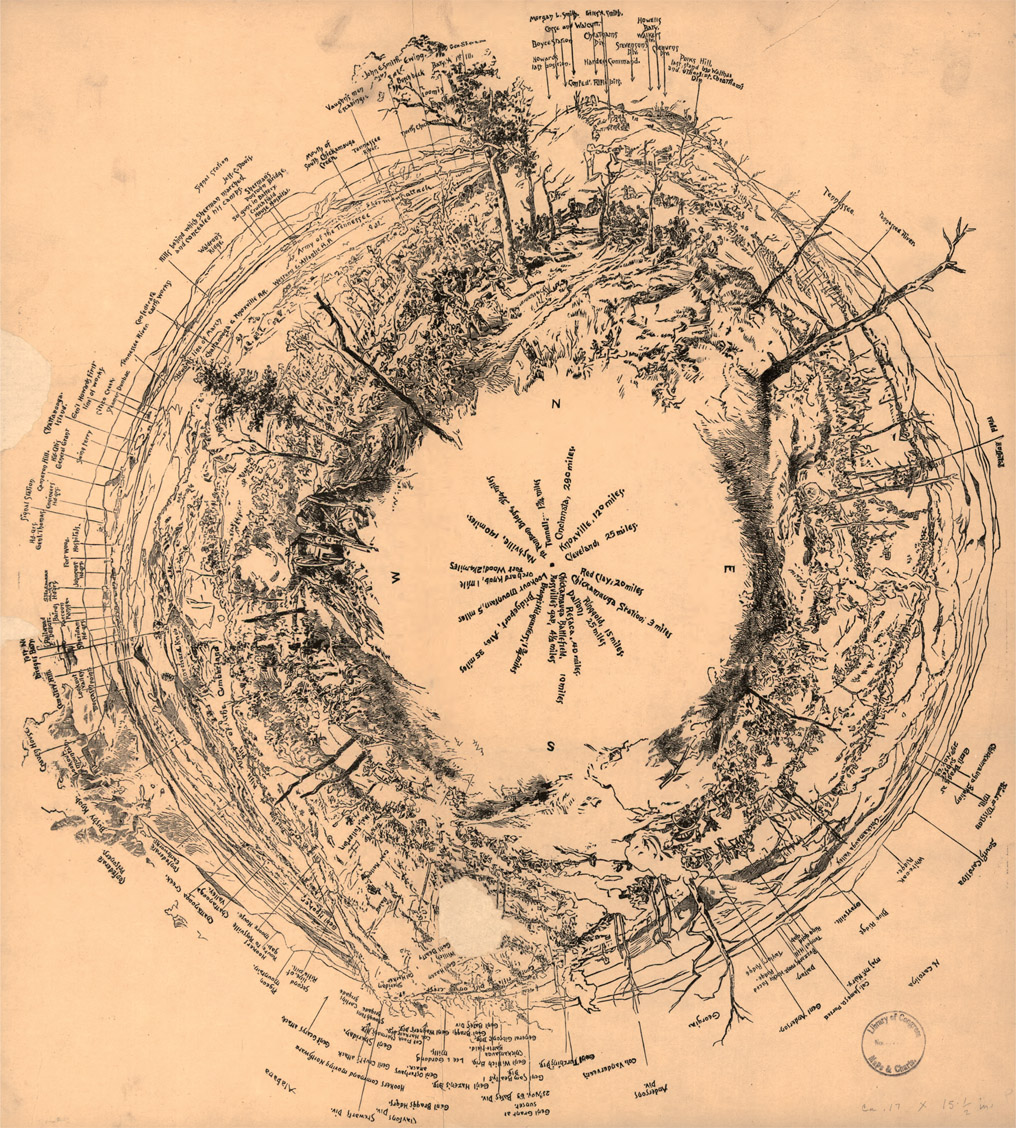

Map of the Battle of Missionary Ridge

Sam Watkins

Sam Watkins was born near Columbia, Tennessee, in 1839, and was attending college there when the war broke out. He immediately quit school and joined Company H, 1st Tennessee Infantry Regiment of the Confederate Army, afraid that the war would soon end and he would not see any action. Self-described “High-Private” Watkins served until the end of the war and amazingly survived in the midst of some of the fiercest fighting in the Western Theater. His unit, soon joined by the 27th Tennessee Infantry Regiment and another independent battalion, fought from just after the First Manassas (First Bull Run) until the surrender of General Joseph Eggleston Johnston’s Army of Tennessee at Greensboro, North Carolina, in April 1865. Although his combined regiments counted some 3,200 men in their ranks throughout the war (by his own estimation), Watkins was one of only 65 original members still standing after four years of fighting, and one of only seven survivors of the original 120 men of Company H.

Although Watkins was in the first line of battle in most of his unit’s engagements, he managed to survive nearly unscathed—seriously wounded only once. He lived to tell about his experiences in one of the greatest memoirs of the Civil War, Company Aytch Or, A Side Show of the Big Show, published in 1882. Originally written in serial form for the Columbia Herald, the book is an emotional and quite philosophical journey through the heart and mind of a combat infantryman separated from all he knows and loves and forced into brutal savagery simply to survive. Watkins took an ironic and somewhat humorous view of “what I saw as a humble private in the rear rank of an infantry regiment,” and his memoir is distinctly different from the legions of other, more self-aggrandizing memoirs and diaries published after the war.

Watkins’s view of the war was from the trenches, and throughout the book he commented that he was not aware of and did not care about the grander strategies; he just marched where he was led and fired when he was told. However, his observations of those mostly vain and self-serving men who led his regiment and army stand out as piercingly accurate. He saw General Braxton Bragg as a “merciless tyrant” that no one in the ranks “ever loved or respected.” About the best thing Watkins could say about Bragg was a simple postwar observation, “But he is dead now.” Watkins thought General John Bell Hood a “failure in every particular” as a general and leader, but “brave, good, noble and gallant,” although he stated that Hood was both mentally and physically incompetent for command.

Johnston was held in much higher regard by Watkins and most of his men and is also well thought of by most modern historians. Watkins said, “He was loved, respected, admired; yea, almost worshipped by his troops…. The veriest coward that was ever born became a brave man and a hero under his manipulation.” While Johnston did not have the support of the higher Confederate command and authorities, his men loved him because he “made us love ourselves,” and Watkins mentioned time and again how they would have followed the little general literally anywhere. Watkins’s own regimental commander, Colonel Hume R. Field, was equally admired; Watkins said that he was the “bravest man, I think, I ever knew” and that the War Department should have placed him in charge of whole armies instead of a mere regiment. Watkins’s view of officers in general, however, was more practical: “I always looked upon officers as harmless personages,” and on the battlefield, “I always shot at privates.”

Watkins went on after the war to marry his beloved Jennie, who was mentioned throughout his memoir, and to raise eight children. He died in Columbia in 1901.

Other Union regiments soon reached the crest and fanned out to both sides, with Confederates making only token resistance before pulling back. With strong attacks now coming from three points atop the ridge, Bragg gave hasty orders to retreat. Mostly in ragged groups and as individual soldiers, some in quickly organized defensive postures, the Confederates streamed back toward Georgia. Hooker was ordered to give chase. Cleburne was ordered to save what was left of the army and to protect their retreat at the north Georgia town of Ringgold.

Receiving these orders just before the Union advance elements arrived, Cleburne elected to set up his defensive position just south of the small town atop two small hills on either side of the rail line. With only a little more than 4,000 men and two small artillery pieces, he knew that he could not withstand a direct assault by Hooker’s 12,000 troops.

Hooker’s men passed through the small town nearly uncontested on the morning of November 27 and immediately set out along the south rail line, led by the 13th Illinois Infantry. Waiting until the Union men were less than 150 yards away, Cleburne ordered both cannon to open fire with both solid shot and canister.

The resulting carnage was extreme, with the 13th Illinois being shot to pieces within minutes, and the flanking regiments on either side of the gap suffering equally immense casualties.

Cleburne kept up his defensive position until shortly after noon, when Union artillery finally arrived on scene. Less than an hour later, he had his men and both artillery pieces safely off the hilltops and heading back toward Dalton. At a cost of 110 casualties, he had both stopped the Union advance and bloodied Hooker to the tune of at least 500 casualties. Many of Hooker’s own men grumbled that this official figure was far too low.

Grant arrived in town later that same day and ordered Hooker to stop the pursuit. Intending to sit out the winter in relative comfort in Chattanooga, he ordered Hooker to stay put for a few days, and then withdraw to the north. Hooker finally left on November 30, burning the small Georgia town in his wake. The bitter fight for control of the gateway city to the Deep South finally came to an end, ironically with a Confederate tactical victory.

Chattanooga Today

Chattanooga is a rapidly growing major city (only one Georgia county along the 100-plus-mile I-75 corridor is not within either metropolitan Chattanooga or Atlanta), and its Civil War heritage stands front and center in its images and advertisements. Curiously, there is relatively little remaining untouched of the most fought-over battleground, Missionary Ridge, and it and some of the other major landmarks are very poorly marked and somewhat hard to find. Due to the city’s growth alongside the meandering Tennessee River, streets are laid out in a confusing array, and it is a bit difficult to find your way around town at first.

Looming over the city like a great granite guardian angel is Lookout Mountain, the focal point for most Civil War–related activities. However, even this obvious landmark suffers from having its only real battleground (the Cravens House) barely marked and easily overlooked. On the positive side, the original Confederate artillery emplacements at the mountain’s crest are still in place, encompassed by a small but tidy park run by the National Park Service. Although no skirmish transpired here, one can get a magnificent view of the city and on clear days see all the major battle landmarks in the area.

Three major interstate highways meet in Chattanooga (I-24, I-59, and I-75), giving easy access to the area from all directions. The suggested route, if convenient, is I-75 north from Atlanta, turning onto I-24 northbound and exiting at exit 178 (Broad Street/Lookout Mountain). An abundance of signs at the end of the ramp will guide you to whichever site or area you wish to visit first.

Take the Battlefield Parkway exit off I-75 (GA 2, exit 141) and travel west about 5 miles, then head south on US 27 about 1 mile to the park. The visitor center is just inside the north entrance and is very well marked.

To follow closely the track that Rosecrans’s retreating army took from Chickamauga to Chattanooga, from Chickamauga stay on US 27 North about 3 miles to a large ridgeline bisecting the state line. This is the left flank of the Confederate Missionary Ridge line. A right turn onto Crest Road will take you across what was once the second and highest set of emplacements, nearly on top of the highest point of the mountain ridge, all the way to the far right flank where Crest Road meets Campbell Street. Please note that nearly all of this avenue is private property, even where historic markers and cannon monuments abound. Also note that this road is narrow and twisting, and parking is difficult to find in most places. A good choice if you are physically able is to park at the Sherman, DeLong, or Iowa Reservations (very few parking slots are at each) and walk along the route.

Today most of the area of operations of this short campaign has been altered or covered up by the rapidly growing city of Chattanooga. The most significant battlegrounds are now federal property, with the National Park Service preserving and operating several separate areas around the city. The largest continuous preserved area consists of Point Park and Lookout Mountain and includes the Cravens House, Point Lookout, and much of the northwest face of the large ridgeline. A very small, 1-city-block-square park encompasses the highest elevation of Orchard Knob, and several small “reservations” dot the top of Missionary Ridge.

We strongly suggest you visit at least the visitor center of Chickamauga Battlefield (see our chapter on Chickamauga for a complete description), which the National Park Service operates as the centerpiece of the two-state Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park.

Battle at Ringgold

| Chanticleer Inn Bed & Breakfast | $$$$ |

1300 Mockingbird Lane

Lookout Mountain, GA

(706) 820-2002

Th Chanticleer, which sits atop Lookout Mountain on a beautiful plateau that borders Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama, is merely minutes from downtown Chattanooga and mountain attractions such as Ruby Falls and the Incline Railway. A full home-made breakfast is included and desserts are offered in the afternoon.

| Chattanooga Choo Choo | $$$$ |

1400 Market St.

Chattanooga, TN 37402

(423) 266-5000

(800) 872-2529

At the Chattanooga Choo Choo hotel complex you can sleep onboard one of its 48 authentic and beautifully restored Victorian train cars or opt to bunk in a more standard-type room. There are restaurants and shopping nearby as well as soothing gardens, swimming pools, and one of the world’s largest working “HO” gauge model railroads.

| Niko’s Southside Grill | $$–$$$ |

1400 Cowart St.

Chattanooga, TN

(423) 266-6511

The fresh ingredients and flavors of the Mediterranean influence Southern-American cuisine at Niko’s Southside Grill, which offers grilled meats, fresh fish, and vegetarian fare.

| Sticky Fingers | $–$$ |

2031 Hamilton Place Blvd.

Chattanooga, TN

(423) 899-7427

Tuck into a rib platter or a combo plate and choose from pulled pork or chicken, hickory-smoked wings, grilled chicken breast, and more. Sticky signature sauces and rubs are also available online.