Shiloh: The Bloodiest Days of 1862

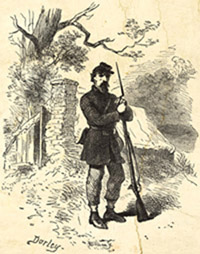

Johnston’s newly organized Army of Mississippi, based in the important rail center of Corinth, Mississippi, steadily built up strength through March 1862. Major General Leonidas Polk, Brigadier General (and former U.S. vice president) John C. Breckinridge, and Major General William J. Hardee brought the remnants of their corps down from Kentucky; Major General Braxton Bragg brought most of his corps north from Pensacola, Florida; and Brigadier General Daniel Ruggles’s division marched east from New Orleans. Other commands scattered around the Deep South detached individual regiments and brigades, which arrived in the northern Mississippi town all through the last two weeks of March. By April 1, Johnston had a roughly organized, ill-trained, and mostly inexperienced force of about 45,000 officers and men under his command.

After taking Fort Henry in the north-central region of Tennessee, Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote sailed his small gunboat fleet down the Tennessee River nearly unmolested all the way to Florence, Alabama, decisively demonstrating just how vulnerable the South was to invasion via the river systems. One of the very few attempts at a Confederate resistance to his mission was on March 1, when Gibson’s Battery of the 1st Louisiana Artillery Regiment, mounted on a bluff just downstream from Savannah, Tennessee, lobbed a few shells at the fleet as they passed. Colonel Alfred Mouton’s infantry from the adjacent 18th Louisiana Infantry joined in, ineffectively shooting up the side of the armored gunboats. Foote returned fire, and the shelling soon stopped.

Andrew Hull Foote

Two weeks later, Union forces started moving south under the overall command of Major General Henry Wager Halleck with two missions: Take control of and repair roads through middle Tennessee, and clear the area of any Confederate forces they encountered. Once all of his forces were concentrated at Savannah, Halleck intended to move farther south, into Mississippi, and destroy the rail junctions in Corinth, Jackson, Humbolt, and Iuka. To accomplish this mission, Halleck had two grand armies: Major General Ulysses S. Grant’s Army of Tennessee and Major General Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio, with a combined total of just under 63,000 men on the march south.

A heavy reconnaissance force under Brigadier General Charles Ferguson Smith (promoted one week later to Major General) arrived in Savannah on March 13, charged by Halleck to seize and hold or at least cut the Memphis & Charleston Railroad at Corinth without engaging the Confederate forces rumored to be gathering in the area. Brigadier General William Tecumseh Sherman arrived from Kentucky the next day, and Smith promptly sent him off toward Eastport, Mississippi, to see if he could cut the railroad there. As he sailed south on the Tennessee River aboard Lieutenant William Gwin’s gunboat, Tyler, Gwin pointed out the location of their earlier skirmish with the Confederate artillery battery. Alarmed at the close presence of the enemy to his intended target, Sherman sent word back to Smith that this location should be occupied in force as soon as possible. Smith agreed and immediately dispatched Brigadier General Stephen Hurlbut’s 4th Division to occupy the small bluff, Pittsburg Landing, about 3 miles northeast of a tiny settlement called Shiloh Church.

Plan of the Battle of Shiloh

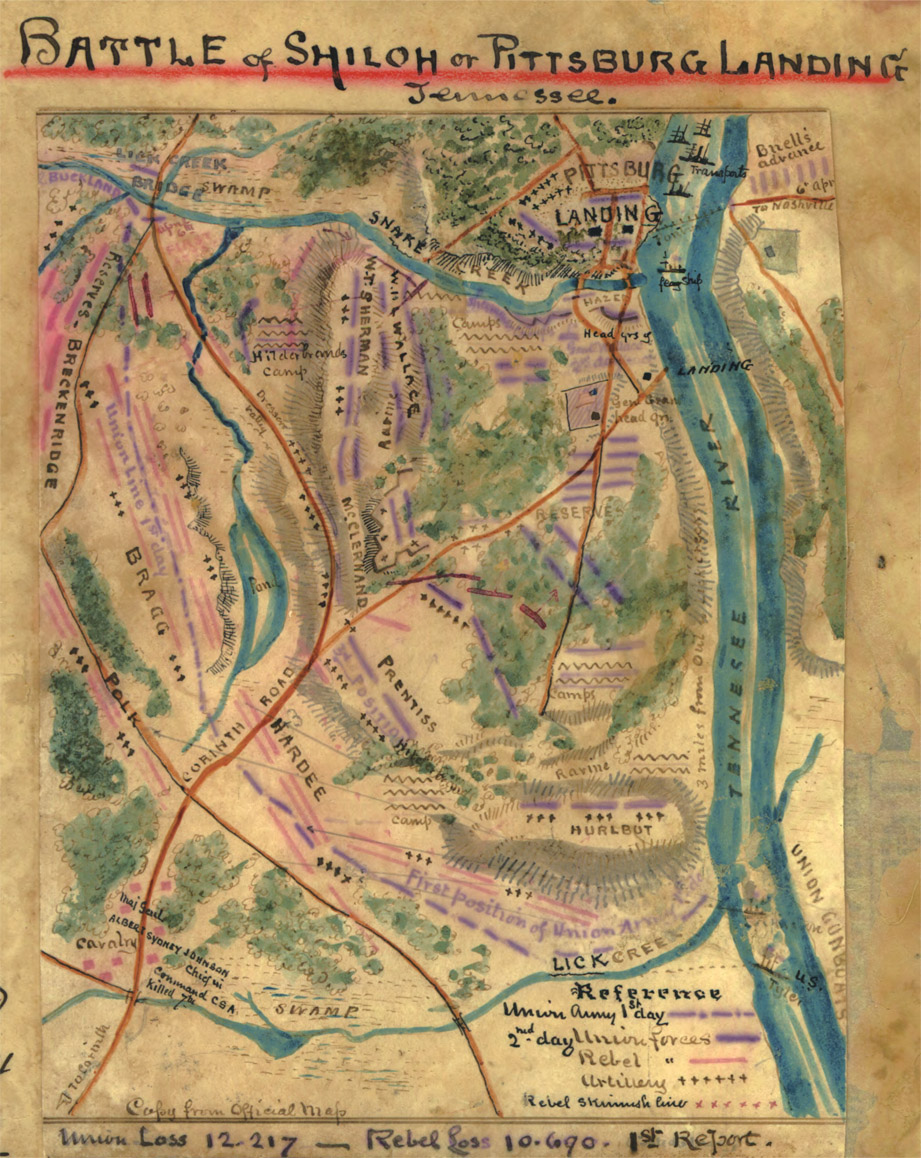

Sherman soon returned from his reconnaissance, after finding Confederates were present in force at his intended target, and joined Hurlbut at Pittsburg Landing. Scouting the area, he reported back to Smith that the area was “important” and easily defended by a relatively small force, although the ground provided a good encampment space for several thousand troops. The few settlers at the landing had fled with the arrival of Union gunboats, and the only “locals” remaining were small-plot farmers scattered about the county. The small Methodist meetinghouse, Shiloh Church, was described by one source as a “rude one-room log cabin, which would make a good corncrib for an Illinois farmer.” Sherman urged Smith to relocate the majority of forces to this small landing, the northernmost road link to their intended target of Corinth, Mississippi.

Shiloh Church

General Grant arrived in Savannah on March 17 to take over direct command of the Tennessee River operation from Smith, setting up his headquarters in the Cherry Mansion on Main Street. He soon ordered his (roughly) 35,000-man force to deploy on the west side of the river, save a small garrison in Savannah, with five divisions to join with Sherman at Pittsburg Landing, and Brigadier General Lewis “Lew” Wallace’s 2nd Division to occupy Crump’s Landing, 6 miles north of Sherman’s position.

Another major Union army, Major General Buell’s Army of the Ohio, was on the way south from Nashville with another 30,000 men (both this figure and Grant’s total command size are wildly disparate in differing accounts). Grant planned to rest his men and wait for Buell’s arrival before starting his operation against Corinth. Although he was aware that the Confederates were present in force just 20 miles away, he believed that they would simply entrench around Corinth and have to be forced out. An attack on Pittsburg Landing was, quite literally, the last thing he expected the Confederates to do.

It took well over a week to transport all the Union forces south to the new position, and the divisions moved inland and encamped in a loose semicircle south of the landing and across the Corinth Road as they arrived. Sherman’s own 5th Division headquarters was just to the west of the Corinth Road. Colonel John A. McDowell’s 1st, Colonel Ralph P. Buckland’s 4th, and Colonel Jesse Hildebrand’s 3rd Brigades deployed from Owl Creek left (east) to just south of Shiloh Church. Colonel David Stuart’s 2nd Brigade of Sherman’s division encamped separately about 2 miles farther east, at the far left and southernmost of the combined Union line, just above Locust Grove Branch at the Hamburg-Savannah Road. Hurlbut’s 4th Division encamped to the left (due east) of Sherman’s main line, with Colonel Nelson G. Williams’s 1st, Colonel James C. Veatch’s 2nd, and Colonel Jacob G. Lauman’s 3rd Brigades arrayed across the intersection of the Corinth and Hamburg-Savannah Roads.

Major General John A. McClernand’s 1st Division deployed behind (north of) Sherman’s. Colonel Abraham M. Hare’s 1st, Colonel C. Carroll Marsh’s 2nd, and Colonel Julius Raith’s 3rd Brigades encamped along the Corinth Road as it ran due west to the Hamburg-Purdy Road intersection. Smith’s division stayed close to Pittsburg Landing itself, Colonel James M. Tuttle’s 1st, Colonel Thomas West Sweeny’s 3rd, and Brigadier General John McArthur’s Brigades encamped just north of the end of the Corinth Road and west to Snake Creek. Brigadier General Benjamin M. Prentiss’s newly organized 6th Division landed and moved the south to the right (west) of Stuart’s Brigade. Colonel Madison Miller’s 2nd and Colonel Everett Peabody’s 1st Brigades made camp to Sherman’s southeast, in the woods across and to the west of the Eastern Corinth Road.

By March 19, all six divisions were in place and comfortably making camp. Smith had been injured while jumping from one boat to another during the landing and was soon forced to hand over command of his 2nd Division to Brigadier General William Harvey Lamb Wallace. Smith died on April 25 of an infection in his foot from the wound.

Johnston was well aware of Grant’s presence to the north of his headquarters and received a message on April 2 that Buell’s force was nearby as well. Still waiting in Corinth for the last of his assigned forces to arrive, Johnston decided that he would go ahead and attack the gathering Union force before Buell’s addition could make it stronger. The orders he issued were simple: March north and engage the enemy between his encampments and the river, turning their left flank and forcing them away from their line of retreat until they were forced to surrender.

Beauregard planned out the tactical details of the coming attack and issued orders to move out on the morning of April 3. Confederate units scattered across upper Mississippi and lower Tennessee were to converge by April 4 at Mickey’s farmhouse, 8 miles south of Pittsburg Landing, where final preparations for the attack would begin. Hardee’s and Bragg’s corps would march north from Corinth, along with one division of Polk’s corps, along the parallel Bark and Pittsburg Landing Roads. Breckinridge’s corps moved north from Burnsville and Polk’s other division (Major General Benjamin Franklin Cheatham’s) would move southeast from Purdy, Tennessee, to join at the rendezvous farm.

The march took much longer than Beauregard had planned due to poor preparation and a steady rain that turned the dirt roads into mud quagmires. It was late in the evening of April 5 before everyone was in position at the junction of Corinth and Bark Roads, with Hardee’s corps arrayed in the front only a half-mile from the Union picket line. Union cavalry patrols had engaged with forward elements of each column on both April 4 and 5, leading Beauregard to ask Johnston to call off the attack. He stated that his carefully scheduled attack plan was now “disrupted” and that with the cavalry attacks, surely all aspects of surprise were long gone. Johnston was adamant about continuing the attack, telling Beauregard, Polk, and Bragg, “Gentlemen, we shall attack at daylight tomorrow.” Moments later, he remarked to one of his staff officers, “I would fight them if they were a million. They can present no greater front between these two creeks than we can, and the more men they crowd in there, the worse we can make it for them.”

All through the dark, damp night, Confederate soldiers lay in the woods, listening to Union bands playing patriotic tunes just yards away. Union soldiers had listened to the Confederates advancing into position all evening and had sent a slew of frantic messages up the chain of command, warning of their presence. Amazingly, all these warnings were ignored by Grant’s staff, who believed they amounted to nothing more than reconnaissance patrols. Grant was still firmly convinced that Johnston’s men were continuing to entrench heavily at Corinth and was only concerned with how difficult it was going to be to “root them out.”

To top off the Union Army’s lack of combat preparedness, Halleck had ordered Grant not to be pulled into a fight that would distract him from his goal of taking Corinth, and Grant followed suit by ordering no patrolling of his own forces, for fear they might engage the enemy “patrols” and create a general battle. His brigade commanders farthest south were growing increasingly nervous, passing on report after report to headquarters that their men were spotting more and more Confederate cavalry, infantry, and even artillery. Their frantic requests for reinforcement, or even for permission to mount their own scouting missions, were denied; their division commanders only reiterated Grant’s orders.

Finally, as darkness fell on April 5, Peabody decided it would be better to beg forgiveness if he was wrong than to ask permission again and gave orders for a combat patrol to go out as early as possible the next morning. At 3 a.m. on April 6, Major James Powell led his 25th Missouri and the 12th Michigan Infantry Regiments, with a total of 250 men, out into the predawn blackness, heading south toward the Corinth Road. They marched southwesterly down a narrow farm lane only about a quarter-mile before running into Confederate cavalry vedettes. Both sides exchanged fire briefly before the Confederate cavalrymen suddenly broke contact and withdrew. Just before 5 a.m. Powell deployed his men into a line-abreast skirmish line and continued southeast, toward Fraley’s cotton field.

Powell’s men moved into the cotton field and soon came under fire. Major Aaron B. Hardcastle’s 3rd Mississippi Battalion had observed the Union troops entering the field and waited until they closed within 90 yards before opening fire. The Union soldiers hit the ground and returned a heavy volume of fire. The exchange lasted until 6:30 a.m., both sides suffering moderate casualties, until Powell observed Hardcastle’s men suddenly disengaging and moving back into the woods. Believing they were retreating, Powell ordered his men up and was preparing to move out again when, to his horror, a mile-wide mass of Confederate soldiers suddenly appeared at the wood line before him—9,000 men of Hardee’s corps on their way north.

The Confederate force was fully up and moving, their surprise attack only slightly tripped up by Powell’s tiny force. Behind Hardee was Bragg’s corps, also in a near-mile-wide line of battle, followed by Polk’s corps in route-march formation (columns of brigades) on the Corinth Road. In the rear, and also in columns of brigades, was Breckinridge’s reserve corps. The whole formation was T-shaped, almost a mile wide, and more than 2 miles long, all moving forward at a quick-time march toward the Union encampments.

Before he was killed and his small patrol force scattered, Powell managed to get word back to Peabody about the general attack. Peabody immediately moved his brigade south to try to aid Powell. Hardee was having a tough time moving his large force north—the Union patrol and skirmishers delayed his general movement, and the terrain was not conducive to moving such a large mass of troops and equipment very quickly. As the two forces moved toward each other, Prentiss rode up to Peabody and began berating him for sending out the patrol and “bringing this battle on.” After a few minutes of argument, Peabody set his men up in a line of battle near his original encampment, while Prentiss set his force up on the left, making ready to engage the oncoming Confederates.

The time was 7 a.m., and the sun was dawning on what looked like a beautiful, cloudless day.

Shiloh National Cemetery Wikipedia Kbh3rd

Hardee’s corps had broken up into the individual brigades, which spread out to engage the Union encampments in an almost 2-mile front. At Spain Field on the Eastern Corinth Road, Brigadier General Adley H. Gladden’s brigade burst out of the wood line directly across from Prentiss’s line, the field itself swept with heavy artillery fire from both sides. A galling fire came from the Union line that staggered the Confederates. Able to stand for only a few minutes, the brigade retreated to the wood line, dragging with them the mortally wounded Gladden, who died later that same day.

Over on the left, at about the same time, Brigadier General Sterling A. M. Wood’s brigade hit Peabody’s right flank, pushing the Union infantry out of their line and back. Johnston, no longer able to stand being out of the line of fire, turned over operations in the rear to Beauregard and rushed forward to lead the battle from the front. Arriving just in time to see Wood’s success and Gladden’s repulse, he ordered all four brigades now up on the line to fix bayonets and assault the Union line at the double-quick, and 9,800 men ran screaming forward into the Union lines.

As his command withered under the assault, Peabody rode forward to rally his men and was hit four times in a matter of minutes by rifle fire as he moved down the line. Finally, in front of his own tent, watching the butternut-clad ranks closing in on him from two sides, Peabody was shot from his saddle, dying instantly. His command completely crumbled, followed shortly by Prentiss’s own men. Even as William Wallace’s and Hurlbut’s brigades moved south to reinforce them, most of the Union infantry had had enough of this fight and retreated toward Pittsburg Landing.

As the Union men broke and ran, the victorious Confederate infantry raced into their just-abandoned encampment and fell over the piles of fresh food and good equipment. Exhortations from their officers to return to the fight did no good, as the brigades and regiments dissolved into a rabble, pillaging the camps. Beauregard and Johnston had to take several precious minutes getting the men back under control and reorganizing them to renew their attack, while the Union line stopped its headlong retreat and fell into new positions for defense.

Johnston ordered Bragg’s corps into the growing battle, splitting his five brigades between the left and right of Hardee’s men and ordering Bragg to take command of the assault on the right flank. On the right, Brigadier General John K. Jackson’s and Brigadier General James R. Chalmers’s brigades briefly joined the rout of Prentiss, while on the left Colonel Preston Pond’s and Brigadier General Patton Anderson’s brigades joined Brigadier General Patrick Ronayne Cleburne’s brigade, which was steadily advancing on Sherman’s position at Shiloh Church. Colonel Randall L. Gibson’s brigade continued straight northeast, in between the two ongoing major assaults, to try to break the Union center and turn Sherman’s left flank. In an attempt to bring the strongest force on his right flank and force the Ohio general’s division away from the river, Johnston brought up Polk’s corps and sent his four brigades into the line alongside Bragg. Hardee was instructed to take direct command of the left flank and to hammer hard on Sherman’s position.

By 9 a.m., 13 Confederate brigades were fully engaged along a nearly 3-mile front, steadily pushing back Union forces. Sherman was soon reinforced by McClernand’s division, while the newly arriving commands of Hurlbut, William Wallace, and McArthur joined in a hastily organized line along with what was left of Prentiss’s brigade to Sherman’s left over to the Hamburg-Savannah Road. Wallace was particularly well positioned along a narrow wagon trace, hardly even a road, that was concealed in an oak forest atop a low ridgeline with a good field of fire before him across the open Duncan field. This position in the center of Grant’s defense line was later referred to as the Sunken Road.

A little after 10:30 a.m., just after Grant finished his visit with Sherman, Polk initiated a gigantic attack on Sherman’s and McClernand’s positions with 10 reinforced brigades, more than two-thirds of the entire Confederate force on the field. The Union lines reeled under the massive attack and soon broke, falling back almost three-quarters of a mile to Jones Field before regrouping. Ironically, this attack produced the exact opposite of what Johnston wanted: It drove the Union line back, but the Union right flank rather than the left, and moved it toward Pittsburg Landing.

At the same time, a smaller attack on the Union left flank by Chalmers’s and Jackson’s brigades slammed into McArthur’s and Stuart’s brigades, wounding both Union commanders and forcing them to retreat. By 11 a.m. a strong Union line was forming, centered on William Wallace’s and Prentiss’s position, hidden along the Sunken Road. Several Confederate attacks on this position were thrown back with heavy losses before Bragg realized what a strong force was concentrated there. As Gibson’s brigade attacked through a dense thicket just east of Duncan Field toward the Sunken Road, Union artillery canister fire and infantry rifle fire raked through the brush. The bullets and canister balls ripping the leaves apart reminded the Confederate infantrymen of a swarm of angry hornets, and they named the place the Hornets’ Nest.

Gibson’s Brigade charging Hurlbut’s troops in the Hornets’ Nest

To the left (west) of the Hornets’ Nest, Bragg once again displayed his irritated impatience and ordered attack after attack around or across Duncan Field on the well-positioned Union line, each one being broken and thrown back in turn. (There is some controversy about the exact nature of this series of attacks; traditionally, the story holds that these attacks went straight across the wide-open field itself, while some more recent research seems to indicate that the attacks actually went down the relatively concealed roads on either side of the field.) To add to Bragg’s problems, Sherman and McClernand managed to regroup their scattered forces and counterattack Hardee’s and Polk’s forces, briefly regaining their own original camps. To reestablish his gains, Beauregard threw his last reserves in the lines, which stopped the Union counterattack. A fierce battle raged between the two armies in Woolf Field, near the Water Oaks Pond just north of the Corinth Road, for just under two hours before the Union troops were once again thrown back to Jones Field.

On the right of the Hornets’ Nest, multiple attacks against Hurlbut and McArthur had been repulsed with heavy losses, until at last some of the Confederate soldiers refused to mount another assault. Riding forward at about 2 p.m., Johnston announced that he would get them going and told the battered force that he would personally lead the next attack. Riding down the line of infantry, he tapped on their bayonets and said, “These must do the work. Men, they are stubborn; we’re going to have to use the bayonet.” He then turned, and with a shouted command for them to follow him, he headed toward the Union left flank. The line of infantry rose with a scream, and four brigades followed Johnston into battle.

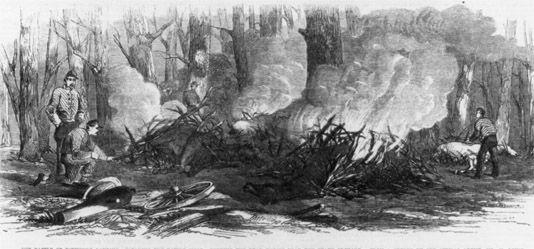

Clearing the battlefield: burning the dead horses in the Peach Orchard

At this same time, Stuart’s brigade, which was directly in front of where Johnston was headed, had nearly completely run out of ammunition, and Stuart ordered a retreat. With Johnston’s men sweeping forward, both Hurlbut’s and McArthur’s flanks were exposed and caved in. Both Union brigades retreated north to the upper end of Bell’s field, near a small peach orchard. Returning a heavy volume of fire on the advancing Confederate force, newly opened peach blossoms fell like snow on the ground as bullets and shot sprayed through the trees.

As Johnston watched the battle unfolding a little after 2:30 p.m. from across the Hamburg-Savannah Road at the southeast corner of Bell’s Field, a bullet ripped through his right leg just below the knee. It probably was fired by one of his own men (the ball came in from the rear); the wound, amazingly, went almost unnoticed by Johnston. Years earlier, Johnston had been struck in the same leg during a duel, which damaged the nerves and possibly numbed the leg to the point that he couldn’t feel a gunshot wound. Minutes later he nearly tumbled from his horse but was caught by his aide, Governor Isham Green Harris of Tennessee, and placed on the ground in a nearby ravine. No medical help was immediately available, as Johnston had sent his personal surgeon out a few minutes earlier to check on some wounded Union prisoners. Harris frantically tore open Johnston’s uniform looking for a significant wound, but dismissed the leg wound as minor. Unfortunately, the leg wound had opened up a major artery, dumping blood into the general’s knee-high boot, and Johnston bled to death within minutes. A tourniquet was later found in the general’s pocket, the quick application of which would have saved his life.

At about 3 p.m. Beauregard was informed that Johnston was dead and took over command of all the Confederate forces in the field. Responding to the growing sounds of battle around the Hornets’ Nest, he ordered most of his left flank to shift over to the right (east) to reinforce the attack there. By doing so he committed two major mistakes. First, his assault that threw back Sherman’s counterattack had been highly successful, pushing the Union right flank far back across the north end of Jones Field and on across the Tilghman Branch, seriously decimating the Union ranks. A follow-up attack could well have split the Union line of battle, sending Sherman and McClernand north and west away from Pittsburg Landing, precisely as Beauregard had originally planned.

Second, the growing battle on his right flank was due to a continued hammering at a relatively small Union force well positioned at the Sunken Road forest area, but which was isolated from retreat, resupply, or reinforcement. Bypassing this position would have undoubtedly resulted in a surrender of the entire command by nightfall and could possibly have led to a successful capture of the steamboat landing itself. Instead, not only did Beauregard order a continued hammering at the isolated Union position, but the shift of units from other isolated fights on the battlefield relieved pressure on other Union units, which were then able to withdraw and reestablish a line along the Hamburg-Savannah and Corinth-Pittsburg Roads, protecting Pittsburg Landing as a landing place for Buell’s rapidly approaching command.

The lack of control Beauregard, or any other high commander, had over the spread-out Confederate forces became painfully obvious in the fight around the Hornets’ Nest; even if Beauregard had not ordered a concentration of forces there, it most likely would have occurred anyway. Individual regiments and brigades that were not already engaged elsewhere and that had rookie or undisciplined commanders started following what Shiloh park ranger Stacy D. Allen called the “make yourself useful policy,” drifting over toward the sound of battle without specific orders to do (or even not to do) so.

With news of the death of Johnston, Bragg shifted over and took direct control of the Confederate right. Hurlbut had established a new line on the north end of the Peach Orchard (which was what Johnston was observing when shot), and despite having an unsupported left flank, he was making things hot for the assaulting Confederates. Just behind his position was a small, shallow pond that had the only fresh water available on this part of the battlefield. Wounded and parched infantrymen and horses alike crawled over to its shores to get a cool drink; many men were too badly wounded to raise their heads once in the pond and drowned in the foot-deep water. Dozens of blue-clad infantry were piled up in heaps of the dead and dying all around the water, their wounds dripping into the damp ground, staining the pond a deep crimson. When Confederates advanced past the ghastly scene, someone remarked what a “bloody pond” it was; the name stuck.

About 4 p.m., Hurlbut’s line finally caved in under the intense Confederate fire, and he retreated up the Hamburg-Savannah Road. Jackson’s and Chalmers’s brigades, now supported by Clanton’s Alabama Cavalry Regiment, rushed through the hole left by Stuart’s and McArthur’s collapse and began advancing north to the east flank of the Hornets’ Nest. About the same time, the seventh direct assault against the Hornets’ Nest was hurled back; bleeding and battered troops of Florida, Louisiana, and Texas pulled back to try to reestablish their ranks.

Brigadier General Ruggles had seen enough. Gathering up as many artillery batteries and individual gun crews as he and his staff could locate, by 4:30 p.m. he had 53 guns parked axle to axle on the west border of Duncan Field, 400 to 500 yards directly across open ground from Wallace’s and Prentiss’s position in the Hornets’ Nest. This was the largest assembly of artillery arrayed against a single target ever seen in the Western Hemisphere at that time. Given the order to fire, the entire line of artillery opened up with a thunderous roar. Ruggles had ordered a mixed load of shot, shell, and canister fired as rapidly as possible. For nearly a half-hour the artillery kept up a fire that averaged three shots per second going into the Union position.

When at last the murderous fire lifted, another Confederate assault charged the Union lines led by Wood, this time sweeping all around both flanks and meeting at the junction of the Hamburg-Savannah and Corinth Roads north of the Hornets’ Nest. As the assault came down upon them, both Wallace and Prentiss ordered a retreat, trying to break out of their position before being surrounded. While leading an Iowa brigade north to the Corinth Road, Wallace was struck on the head; he lived a few more days and died in his wife’s arms in nearby Savannah. With the death of Wallace and the impossibility of his situation painfully obvious, Prentiss finally surrendered what was left of the two brigades—himself and 2,250 men—a little after 5:30 p.m., the largest surrender to date in the war.

While the remainder of his forces were slowly dissolving away to the west and south, Grant hurriedly brought up as much artillery and as many men as he could scrape together to guard the critically important landing. By the time the last survivors of the Hornets’ Nest surrendered, Grant had about 70 cannon and 20,000 infantrymen in line for defense. His 1¼-mile-long last-ditch defense line started at Dill Branch on the left flank (east), where it entered the Tennessee River just south of the landing, ran due west to the Hamburg-Savannah Road, then turned north along the road to just north of Perry’s Field. The majority of artillery was placed just below the crest of the low, rolling hills above the landing, obviously intended to be used for point defense should an evacuation prove necessary.

As the last artillery batteries pulled into position, the vanguard of Buell’s Army of the Ohio finally appeared across the river from the landing. Hastily transported across the river, Nelson’s division had to force their way through several thousand Union soldiers desperately trying to flee the battlefield. As they fell into place, one last Confederate charge came up the hill at them.

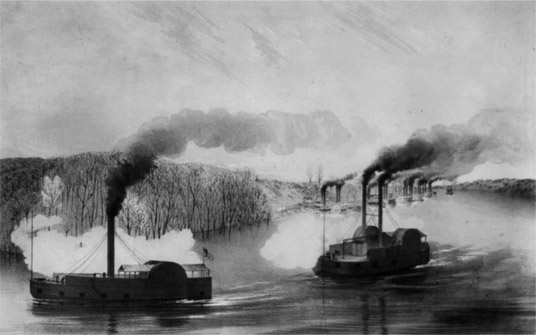

About 6 p.m., Jackson’s and Chalmers’s brigades moved through the Dill Branch ravine, aiming straight at the hill above Pittsburg Landing. The mass of Union artillery opened fire on them, joined by the Union gunboats Lexington and Tyler with their 8-inch guns. As these two brigades struggled through the flooded branch and rugged ravine, the remnants of Anderson’s, Stephens’s, and Wood’s brigades joined in the attack without overall coordination, a mere 8,000 Confederates attacking uphill and across rugged terrain without artillery support into a strongly fortified Union position manned by at least 10,000 infantry, studded with nearly 40 artillery pieces, and with reinforcements hustling down the road to join in.

Within minutes the Confederate assault petered out, the butternut-clad infantry slipping away in squads and companies to find shelter as the early spring sun set on the horizon. Only Chalmers’s and Jackson’s infantrymen managed to briefly get within rifle range of the Union line; most of them were out of ammunition by that point, intent on closing and using the bayonet.

Beauregard sent word to all his commanders to suspend the attack for the night and pull back to the captured Union encampments. One by one, guns fell silent as the Confederates moved out of range. Units were in serious disarray on both sides, and the long night would be needed just to restore some semblance of order. Some Confederate units had not slept more than naps in two days, and most had not eaten since the day before. Although warned that Buell was nearby, Beauregard disregarded the threat and decided along with Bragg, Polk, and Hardee that the best plan was to rest and wait until daylight to get the army back into proper organization and to renew the assault. All felt that the only task remaining was to sweep up Grant’s line and force him to retire north, a task that should not take more than a few hours.

The gunboats Tyler and Lexington support Federal troops at Shiloh.

Losses on both sides were very high in the day-long battle, with both sides suffering near-identical casualties—almost 8,500 dead, wounded, and missing. The critical factor in these losses, however, was that Grant had reinforcements on the way, while Beauregard was on his own, without hope of relief.

Just as fighting was ending for the day, Lew Wallace’s division finally arrived on the battlefield. It was only 6 miles away when sent for at 11 a.m.; a march that should have taken about two hours had taken more than seven. Grant was livid, but mistakes in navigation had simply tied up the men all day and left them wandering around muddy country roads north of the battlefield while Wallace tried to find the right one to lead him to Sherman’s support. Grant used Wallace’s tardiness later as an excuse to blame away some of the Union Army’s disaster of April 6, but if he had shown up on time where he was headed, his division would have entered the brunt of the fighting around Shiloh Church and most likely would have been routed as Sherman and McClernand had been. Wallace, the postwar author of Ben-Hur, lived with this series of mistakes the rest of his life, dying with the thought on his mind that his errors may have killed Union soldiers.

As the two battered armies settled down for a fitful rest, clouds gathered and a heavy, cold rain started to fall shortly after 10 p.m. Grant wandered around his headquarters, reluctant to go inside, as the building had been converted to a hospital, and the shrieking wounded and charnel-house atmosphere were simply unendurable. Sherman, wounded again in the shoulder during the afternoon, finally found him under a large oak tree, holding a lantern and smoking one of his ever-present cigars. “Well, Grant, we’ve had the devil’s own day, haven’t we?” remarked the fiery Ohioan. Grant, far from demoralized, replied simply, “Yes. Lick ‘em tomorrow, though.”

William Tecumseh Sherman

Just the mention of this Union general’s name is enough to raise the blood pressure of many a loyal Southerner. In 1998 a land transaction in South Carolina was completed under a number of rather unusual conditions, including that no one named Sherman or whose name could be unscrambled to spell out Sherman could ever be permitted to purchase that property.

Born in Lancaster, Ohio, in 1820, Sherman was sent from his home to live with the family of Senator Thomas Ewing after his own father died in 1829. Nicknamed “Cump” by his boyhood friends, Sherman was appointed to West Point by his foster father, graduating in 1840 ranked 6th out of 42. His first assignment as a brevet 2nd lieutenant was to the 3rd Artillery, and through the 1840s and early 1850s he was assigned to posts in Florida, South Carolina, Georgia, and California. During the Mexican War he saw very little action, assigned as an aide to Captain Philip Kearny and Colonel Richard B. Mason. Assigned to a post in California after the war, he resigned his commission as a captain and went to work in the banking industry there. In 1857 he moved to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and opened a law and real estate practice, moving on to become superintendent of the Louisiana State Seminary of Learning and Military Academy in 1859. He remained in that capacity until Louisiana seceded in 1861.

With the outbreak of war, Sherman was quickly recommissioned, this time at the rank of colonel, and placed in command of the 13th Infantry Regiment. Rapid promotions being the norm in the early, confused months of the war, he was soon promoted to command of a brigade in Brigadier General Irvin McDowell’s army, defeated in battle shortly thereafter at the First Manassas. Sherman was soon promoted to brigadier general and sent to Kentucky as second in command to Brigadier General Robert Anderson. When Anderson became too ill to lead a short time later, Sherman assumed command. Sherman was never what one would describe as a temperate or politic man, and when the press questioned him endlessly about his plans (similar to today’s braying mob at press conferences), his irritated, snappish responses caused the newspapers to start rumors that he was “off in the head,” a charge that would haunt him throughout the war. Various sources report that Sherman suffered a mild mental breakdown during this period.

The Union high command, affected by the news stories and showing a lack of leadership common throughout the war, reassigned Sherman, who was doubtlessly relieved to be out of such a bad situation. He was sent to command the 5th Infantry Division of Major General Henry West Halleck’s army in Missouri, which was building up to invade western Tennessee and northern Mississippi. In April 1862, as part of Major General Ulysses S. Grant’s corps, Sherman’s division was encamped near Shiloh Church, 23 miles north of their target of Corinth, Mississippi, when they were suddenly attacked by 25,000 men of General Albert Sydney Johnston’s combined Confederate Army of the West. Although wounded in the early phases of the battle, Sherman stayed in the field and helped organize a successful counterattack.

When Grant replaced Halleck in command of all the western armies, Sherman, now promoted to major general, stayed with him, commanding a corps. Sherman successfully fought guerrillas at Memphis and in the grand land-water campaign at Vicksburg, before being sent to relieve the besieged forces at Chattanooga. In March 1864 Grant was recalled east to take over as commander in chief of all Union armies, leaving his friend Sherman in command of the western armies. Building up his Army of Tennessee in Chattanooga over the winter and spring of 1863–64, Sherman unleashed the 100,000-man force on northern Georgia in May. Slowly pushing his Confederate opponent (and friend), General Joseph Eggleston Johnston, back toward the defenses of Atlanta, Sherman did not receive a real break until Johnston was replaced by Lieutenant General John Bell Hood at the end of July. Five weeks later, the campaign came to a close, with Sherman firmly in control of Atlanta and northern Georgia. With this, the war in the Western Theater was for all practical purposes over.

Sherman’s reputation today largely stems from his March to the Sea, the Georgia campaign where he brought 60,000 men from Atlanta to Savannah, but truthfully, this wasn’t much of a military campaign. Resistance was almost nonexistent, consisting of one small battle and a handful of skirmishes. Sherman’s biggest problem on the march was feeding his vast army off the depleted countryside. However, the behavior of his “bummers” through this march and the subsequent one through the Carolinas, encouraged by the “total war”–thinking commander, (continued on next page) gave him his reputation as a thief and firebug. He ordered that anything of military value be taken or burned, and his men applied this order very liberally. Leaving only 10 percent of the buildings standing in their wake in Atlanta, his army burned and looted their way across a 40- to 60-mile-wide swath through central and south Georgia and an equally wide, depleted path in South and North Carolina. The destruction was so complete that certain buildings in those areas today are celebrated for their survival.

After accepting Johnston’s surrender of the Western Theater armies in April 1865, Sherman turned to fighting and rounding up Indians in the far West. When his old friend Grant was elected president, he appointed Sherman a full general and placed him as commander in chief of the army. He finally retired from the service in 1886 and died in New York in 1891. One of the pallbearers at his funeral was none other than his friend and ancient nemesis, Joseph Johnston.

Grant ordered the gunboats stationed in the Tennessee River to keep up a steady bombardment all night, but their shells mainly burst among the Union wounded still left out in the killing fields. The Confederates had pulled back to the former Union encampments and were comfortably housed in their enemies’ tents while they feasted on the abundant supplies. Cleburne, sitting in a tent and watching the shells burst around the bodies of the Union dead and wounded, remarked, “History records few instances of more reckless inhumanity than this.”

As the night wore on, Buell’s Army of the Ohio traveled south from Savannah and crossed over into Grant’s line; by 8 a.m. on April 7 more than 13,000 fresh, well-equipped troops stood ready to renew the fight. Beauregard had no reinforcements to bring up but remained optimistic. Upon hearing a false report that Buell’s force was actually moving on Decatur, Alabama, he fired off a report to Richmond that he had “won a complete victory” that day and would finish off Grant’s force in the morning.

As morning approached, Grant had about 45,000 men ready for an assault on the Confederate positions, most of them well rested and spoiling for a fight, while Beauregard could field only about 28,000 (some accounts say 20,000) tired men not yet reformed into their brigades, or even completely resupplied.

Just before dawn on Monday morning, April 7, 1862, Grant ordered his combined armies to move out. Buell’s fresh troops moved nearly due south, toward Hardee’s and Breckinridge’s lines, while Grant’s resupplied and reinforced army moved southwest in two lines of battle toward Bragg’s and Polk’s lines. Led by heavy artillery fire from the massed Union guns, the sudden dawn attack caught their Confederate opponents completely by surprise, turning the tables from the day before.

No organization existed; the Confederate infantry had simply dropped in place the night before at whatever camp was handy, and few had bothered to resupply their depleted cartridge boxes from the piles of captured Union ammunition boxes scattered everywhere. Most likely believed that, if Grant were smart, he would leave the field during the night rather than suffer another “lickin’.”

To top off Beauregard’s problems, Polk had withdrawn his corps nearly 4 miles to the south, to the site of his previous night’s encampment, and it took nearly two hours after the Union’s initial attack to locate him and get his corps moving. Once in the line, none of the four corps commanders actually commanded his entire corps as the units intermingled and were confusingly arrayed in the haste to mount a defense.

With great effort, the four Confederate corps commanders managed to form a meandering defense line in the face of the Union attack, roughly running northwest to southeast from the Jones Field across Duncan Field south of the Hornets’ Nest to just about the place of Johnston’s death the day before, on the Hamburg-Savannah Road. They managed to hold this line under great pressure until about 11 a.m., when a general pull-back in order was called. The line moved back intact about a half-mile on the left and extended another half-mile on the right to counter increased pressure from Buell’s forces on its right flank.

By noon the Confederate line had again pulled back under pressure to a line centered on Shiloh Church. Union units all along the line kept up a steady artillery and infantry fire; Grant’s plan was to simply roll south using his fresh troops to grind up the tired Confederate infantry. The plan worked quite well; several counterattacks by Hardee, Breckinridge, and Bragg were absorbed and thrown back with heavy casualties.

By 1 p.m. it was obvious to Beauregard that not only were they not going to be able to win this battle, but he was also in danger of being swept in pieces from the field. He hesitated for nearly an hour, however, before finally passing orders down the line for his commands to break contact and retreat to Corinth. Several artillery batteries repositioned at Shiloh Church, along with Colonel Winfield S. Statham’s and Colonel Robert P. Trabue’s brigades of Breckinridge’s corps, to act as a heavy rear guard.

Getting to Shiloh

Shiloh is in a relatively remote part of Tennessee, very close to the common border of Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi. The nearest city with access to an interstate highway is Jackson (I-40 between Memphis and Nashville), 52 miles to the northwest via US 64 and US 45. The nearest large cities are Memphis, 113 miles west on US 64, and Chattanooga, 204 miles east via US 64 and I-24.

As we came in to Shiloh from the east, we took I-24 north out of Chattanooga to exit 134 (Monteagle), turning west on US 41 Alternate through Sewanee and turning west/south on US 64 just outside Winchester. US 64 is a pleasant but long journey through southern Tennessee about 140 miles to Savannah. This small town lies just 10 miles northeast of the national military park. Continue on US 64 until you cross the Tennessee River into Crump, and then take the first major road intersection to the left, TN 22, which runs straight through the park.

Shiloh today is a quiet, wooded, and serene place little changed overall from 1862. The surrounding towns are larger, and instead of steamboats on the adjoining Tennessee River, there are pontoon boats and fishermen. It is just as remote, though, and one can easily imagine the reaction of Grant’s inexperienced troops placed in such a “crude and hostile environment,” as one Ohio private wrote. The majority of the original battlefield has been preserved as a national military park and is operated by the National Park Service.

The original little wooden Shiloh Church is long gone, but the congregation is still present and meets every Sunday in a brick-and-stone sanctuary built on the same spot in 1949. A replica of the original church has recently been constructed near this site. The surrounding graveyard has some gravestones that were present when Sherman made his stand here, and most of the roads both armies walked down are still in existence, albeit now paved and improved.

Be aware that the weather in this area tends to be extremely hot during summer; snow and ice are not unknown during the winter, and violent weather (including tornadoes) is often a feature of springtime. Visits to some of the battlefield areas involve quite a bit of walking, so make sure to dress appropriately and carry sufficient water with you during hot weather.

Cavalrymen were ordered to hastily destroy all the Union equipment and supplies that the retreating infantry weren’t able to carry off with them. As the piles of broken tents and wagons blazed into the stormy afternoon, Breckinridge broke off contact and withdrew in good order at the rear of the long Confederate column. As the Confederate line moved south about 5 p.m., Grant’s exhausted infantry was simply too tired to follow. Breckinridge stopped for the night and redeployed at the intersection of Bark and Corinth Roads. No Union force challenged their rest, and at dawn he moved south into Corinth.

Grant had won a magnificent victory, but at a heavy price. Of his 65,000-man combined army (with Buell’s), 1,754 were killed, 8,408 wounded, and 2,885 captured or missing in action—a fifth of his whole command. The tattered remnants of his proud regiments were too shot up and exhausted after two solid days of combat to pursue the retreating Confederates, who made it back into Mississippi without resistance.

Beauregard suffered worse; in addition to losing the beloved army commander Albert Sidney Johnston, he had to report losses of 1,728 killed, 8,012 wounded, and 959 missing or captured. This loss of 10,699 soldiers constituted nearly a fourth of all the men he had helped bring into the campaign. Once back in Corinth, he ordered the town prepared for defense against an attack by Grant and set about turning nearly the entire small community into one vast hospital for his thousands of wounded.

Cherry Mansion

265 Main St.

Savannah, TN

(731) 925-8181 (Hardin County Tourism)

This 1830 two-story house was used by Grant as his headquarters immediately before and after the battle. Tours are offered by appointment only. The grounds are open for strolling, and a nearby monument commemorates Grant’s stay here.

Shiloh National Military Park

1055 Pittsburgh Landing Rd.

Shiloh, TN

(731) 689-5696

This 3,960-acre park covers all but a small fraction of the original battlefield and contains all the significant sites. A very nicely appointed visitor center graces the hill just above Grant’s last line of defense, containing a small but well-presented set of artifacts, a friendly and quite knowledgeable staff, and a 25-minute film, Shiloh—Portrait of a Battle, shown every 90 minutes. We recommend it for its good description of both the battle and events that led up to it.

Just across the parking lot is the bookstore, run by a private concessionaire, Eastern National, which has made a great effort to provide a well-stocked and well-selected choice of books, maps, and some nice souvenirs. An unusual item we noticed was small ceramic replicas of some of the state monuments scattered around the park. Eastern National has earned our gratitude for resisting promotion of the “anything with a rebel flag on it” school of souvenir shop. Behind the bookstore is a selection of soft drink and snack machines, restrooms, and a pay phone.

Make sure you pick up a copy of the driving tour brochure in the visitor center, and we recommend arming yourself with a copy of Trailhead Graphics’ “Shiloh National Military Park” battlefield map, available in the bookstore. The driving tour will get you around the major sites in a reasonable amount of time, while Trailhead’s map lists the exact location of every one of the 151 monuments, 600 or so unit position markers, and 200 artillery pieces. A very nice adjunct to these maps is the Guide to the Battle of Shiloh by Jay Luvass, Stephen Bowman, and Leonard Fullenkamp, part of the excellent U.S. Army War College “Guides to Civil War Battles” series. This battle was a very large, confusing, and widespread campaign, and this book was our constant companion when trying to understand certain movements and actions—although as it is meant for professional historians and military officers, it, too, tends to be confusing and hard to understand in places! It is available in the park’s bookstore.

Directly adjacent to the bookstore is the Shiloh National Cemetery, the final resting place of 1,227 known and 2,416 unknown Union dead from this battle and others nearby. A unit of the national cemetery system, it also contains remains of veterans from later wars. Grant’s headquarters was located in the middle of this field and is marked by a vertical cannon barrel.

All across the battlefield are mass graves of the Confederate dead, hastily buried and mostly unmarked by the Union troops, who stayed on the field for another six weeks. Five of the mass graves have been located and marked; one is on the driving tour. Admission to the park gets you a dashboard card for your car at the visitor center, which is valid for seven days. Closed Christmas.

Tennessee River Museum

495 Main St.

Savannah, TN

(731) 925-2364

(800) 552-FUNN (3866)

Housed in the chamber of commerce building next to the county courthouse, this small museum has set a daunting task for itself, which has partially been fulfilled: to chronicle the life and times of the Tennessee River Valley from prehistoric times to today. Still obviously under development, several exhibits tell the story of the Native American mound builders, the Trail of Tears, the Golden Age of Steamboats, and the river gunboats used during the battle here.

The closest cities with a selection of services are Savannah, about 10 miles north of the park via TN 22 and US 64, and Corinth, Mississippi, about 23 miles south via TN 22 and US 45.

The small settlement of Shiloh, just outside the south park boundary at the intersection of TN 22 and TN 142, has exactly one service station/convenience store, one restaurant, and one souvenir shop.

There are very few accommodations in the immediate area of the battlefield park, but the usual array of chain establishments are in Savannah to the northeast and Corinth to the south; of the two, Corinth is farther away but has a larger selection.

There is nothing available in the park besides soft drink and candy machines, so you will have to drive either north or south on TN 22 for anything more substantial. As with the accommodation situation, the usual array of fast-food and lower-end sit-down chains are available either way, but a wider array of offerings is in Corinth.

| The Catfish Hotel | $–$$ |

1140 Hagy Lane

Shiloh, TN

(731) 689-3327

The Catfish Hotel was once just a little shack built in 1825 by a family who farmed and fished the surrounding land. It was later occupied by Union soldiers during the Battle of Shiloh. It is located just north of the Shiloh Battlefield Visitor Center and offers great meals as well as fantastic views of the Tennessee River while dining.