Other Tennessee Battlefields

The 16th state to be admitted to the Union (1796), Tennessee was the last to secede and join the new Confederacy and did so, ironically, partly as a reaction to a request by President Lincoln for troops to put down the “insurrection” in other states. Parts of the state were heavily pro-Union, most notably the far-eastern, mountainous sections that were part of the one-time separate state of Franklin. Some of the largest battles in the Western Theater were fought here, although the Union controlled most of the state for most of the war. As a final irony, even Lincoln’s September 1862 Emancipation Proclamation did not apply to Tennessee; by that time it was fully under Union control and no longer “presently in rebellion.”

It is tempting to note that Tennessee was also the first state to be brought back under Union control, as is so often claimed, but the rather “fuzzy” situations in Maryland and Kentucky raise some doubts here. Kentucky was proclaimed by its legislature to be officially neutral, and several of Maryland’s most influential legislators were arrested by Federal authorities to prevent a vote of secession, but both were slaveholding states with very strong ties to the Confederacy. Both supplied combat troops and supplies to the South, even though both were ruled by what has been referred to as a “hostile foreign government,” i.e., the United States.

Battles, skirmishes, and raids occurred across the entire length and breadth of Tennessee, although the largest occurred in the central and southern portions of the state. Outside the major battles that are discussed in other chapters, these actions can be divided into three broad categories: the campaigns for Knoxville, the Battle of Stones River, and the struggle for control of the northwestern rivers. Smaller actions ranged all through the state largely as a result of Major General Nathan B. Forrest’s and Colonel John Hunt Morgan’s cavalry raids for the South.

Today the third-largest city in Tennessee, during the Civil War Knoxville was a strong Confederate outpost in an otherwise remote area that was heavily pro-Union. It also was the key communication and transportation point between the Confederate armies in Tennessee and Virginia.

President Abraham Lincoln had a personal interest in the Unionists in Knoxville; like him, they were small-plot farmers strongly opposed to slavery and secession and strong advocates of the Republican stance. For this, their pro-Confederacy neighbors persecuted them, sometimes to the point of torture and murder. Early in 1863 Lincoln directed his western armies to take Knoxville as soon as possible to “relieve” the Unionists in the area.

The combined Union armies in the west had had their fill of fighting since shortly after the war began, and for nearly two years had been unable to mount an offensive in force into the eastern reaches of the Confederate heartland. Major General Ulysses S. Grant, on siege outside Vicksburg in May and June of 1863, had been urging his fellow Union army generals to launch an offensive in central Tennessee in order to cut off General Joseph Eggleston Johnston’s attempts to relieve the embattled Confederate garrison there. Major General William Stake “Rosy” Rosecrans, comfortably encamped with his Union Army of the Cumberland in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, finally and reluctantly agreed to mount an offensive. On June 23 his army moved out and slogged southward through a cold rain toward the Confederate force at Tullahoma.

General Braxton Bragg had sent a good portion of his Confederate Army of Tennessee to Mississippi and was at that time in no shape to stand up to Rosecrans. During the nine days it took the Union force to arrive, Bragg withdrew all of his remaining men and most of his supplies south to Chattanooga, where he heavily entrenched. Rosecrans took Tullahoma without a shot being fired, and then he did nothing for the next eight weeks while Bragg reinforced both his army and his fortifications at Chattanooga.

With increasing pressure from Lincoln, Rosecrans finally moved out eastward to retake the strongly pro-Union east Tennessee from Confederate control. Rosecrans was to take the vital rail and manufacturing center at Chattanooga, while Major General Ambrose Everett Burnside’s Army of the Ohio was to march from their base in Cincinnati to take Knoxville.

Getting to Knoxville

Knoxville is in the eastern reaches of Tennessee, accessed by I-75 from the north and south and I-40 from the east and west. Nashville is 175 miles west on I-40, Chattanooga is 112 miles south on I-75, Asheville is 107 miles east on I-40, and Lexington, Kentucky, is 173 miles north on I-75. US 441 goes southeast about 30 miles to Pigeon Forge and Gatlinburg, directly adjacent to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, a nice addition to tours in the area.

All the defense works around Knoxville, including Fort Sanders, long ago disappeared. Most of the city then is on what is today the University of Tennessee at Knoxville campus, near the intersection of US 11/70 and US 129. A few of the older buildings on campus were used as barracks for both armies during their occupations.

The university has a marker commemorating Fort Sanders in front of Sophronia Strong Hall, unfortunately located 2 blocks south of the actual location. The United Daughters of the Confederacy have placed a monument at the actual location, the hill nearest the corner of 17th Street and Laurel Avenue.

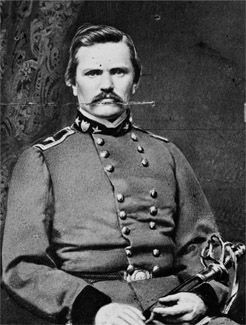

Major General Simon Bolivar Buckner

The Confederate Department of East Tennessee was commanded at the time by Major General Simon Bolivar Buckner, newly sent up from Mobile to prepare for Burnside’s threat to the region. In Knoxville was a single infantry brigade and two cavalry brigades—all told, only 2,500 men. The northern approach to the city, Cumberland Gap at the Kentucky state line, was guarded by only a single brigade under the command of Brigadier General John W. Frazer, with 2,000 men and 14 pieces of artillery in total.

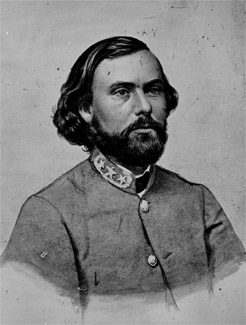

Brigadier General John W. Frazer

Before Burnside could even get a good start southward, Rosecrans was threatening Chattanooga, and Buckner was ordered to withdraw from Knoxville to help defend the river and rail center to the west. Leaving Frazer in place at Cumberland Gap and one infantry brigade just east of Knoxville, Buckner left town with all the rest of his infantry and cavalry on August 16.

Cumberland Gap had been taken and lost three previous times by Union forces, and Burnside knew better than to directly confront Frazer’s strong defensive position there. His Army of the Ohio then consisted of Brigadier General Robert Brown Potter’s IX and Major General George Lucas Hartsuff’s XXIII Corps, with about 24,000 men total. Sending one division of the advance brigade of the IX Corps to “demonstrate” against Frazer’s command, Burnside moved the rest of his force several miles to the west, crossing the Cumberland Mountains at Winter’s Gap and Big Creek Gap.

Burnside’s command entered Knoxville unopposed on September 3, welcomed by a large crowd of local Unionists. The single Confederate infantry brigade still present prudently declined to engage the overwhelmingly superior Union force and quietly slipped out of the area to join Buckner in Chattanooga. Burnside detached two brigades to confront Frazer’s entrenched Cumberland Gap position from the south; faced with strong Union forces on either side of the gap, Frazer surrendered his command without a fight on September 9.

Burnside, the Union general better known for his namesake facial hair than his military prowess, set up his headquarters in newly captured Knoxville with the intent of using it as a base to raid western Virginia. So intent was he on this task that he ignored a number of requests for help from Rosecrans, first as the fight at Chickamauga was going badly and again when Chattanooga was besieged.

As Bragg made his plans to break back into Union-held Chattanooga in late 1863, he committed a grievous tactical error and ordered Lieutenant General James “Old Pete” Longstreet to take his corps (nearly a third of Bragg’s entire army) to the east and retake Knoxville. Bragg, a personal friend of President Jefferson Davis but an erratic commander and occasionally poor judge on the battlefield, had a personal feud with the South Carolinian and sent him east mainly just to be rid of him.

Longstreet’s 10,000-man force consisted of Major General Lafayette McLaw’s and Brigadier General Micah Jenkins’s division (of Lieutenant General John Bell Hood’s corps) and Colonel Robert Porter Alexander’s and Major Alexander Leyden’s Artillery Battalions (35 guns total), along with Major General Joseph “Fighting Joe” Wheeler’s Cavalry Corps with 5,000 men. The Confederate task force moved out of the Chattanooga line on November 5, riding on trains so old and tracks so worn out that nearly everyone had to get off and walk up each hill. It took eight days to cover the first 60 miles and another three to finally reach the Tennessee River 30 miles west of Knoxville. Wheeler’s cavalry had been sent ahead to probe around the city and find an undefended high spot to set up artillery.

Burnside had not been idle in the intervening months, setting up a ring of strong earthwork forts and redoubts around the hilly city. Wheeler was soon forced to report back to Longstreet that there was no undefended high ground from which to launch an attack. While Longstreet made ready to cross the Tennessee River and pondered just how to launch his attack, Burnside decided to take the offensive.

Burnside was well known in the Union Army as being a poor battlefield commander, which he would be the first to admit, and the decision to leave the strong defenses of Knoxville and personally lead a 5,000-man force west to directly confront the oncoming Confederate troops was a poor one, indeed. The lead elements of both forces first encountered each other at the Tennessee River between Loudon and Lenoir City. All the bridges and ferries there had been burned in an effort to further slow down Longstreet’s advance.

Longstreet was delighted. With Burnside out of the city, all he needed to do was find a quick ford and race around him, cutting the Union force off from its home base. Wheeler reported in short order that a suitable crossing was only a-half-mile to the south, at Huff’s Ferry. Longstreet quickly rerouted his army there and crossed a still-under-construction pontoon bridge just after noon. Burnside was still unaware that Longstreet had drawn so close and was caught completely by surprise when the first elements of the Confederate force engaged his pickets in Lenoir City just at dusk.

Rapidly backpedaling, Burnside managed to hold off the ineffective assaults and withdrew his forces intact through Concord, heading for Campbell’s Station (today known as Farragut). The Union forces left Lenoir City at dawn on November 16, “temporarily abandoning the valley of the Tennessee south of Loudon,” according to Brigadier General Orlando M. Poe of the North, and making all speed back to the fortifications under construction in Knoxville. Longstreet realized that if he could reach the crossroads at Campbell’s Station first, he could cut off Burnside’s force from the main body in Knoxville and defeat both in turn. Almost a footrace ensued, with both armies racing up parallel roads toward the small crossroads settlement.

Burnside’s troops, led by Colonel John F. Hartranft’s 2nd Division, won the race, but just barely. Hartranft deployed his men facing west on the Kingston Road just before noon to cover the baggage train that continued east toward Knoxville without stopping. The rest of Burnside’s combat troops formed a second line about a half-mile behind Hartranft’s. About 15 minutes later, the vanguard of Longstreet’s force, McLaw’s division, arrived and immediately assaulted the Union line still forming up.

McLaw’s attack was at first successful, driving the left of the Union line back and forcing it to re-form to the rear. Jenkins had been ordered to simultaneously strike the Union right, but his maneuver was ineffective and the line held. With two more Union divisions now in place and ready just behind him, Hartranft broke contact just after noon and withdrew to the new Union line of battle.

Longstreet’s men stayed in close contact, assaulting the Union line on the right and center just as Hartranft fell into position, again without any gain. As the attacks continued, Burnside ordered his force to fall back under pressure to a ridgeline about three-fourths of a mile to their rear. The Union withdrawal was brilliantly executed, the troops keeping up a steady fire while slowly moving back to the higher ground. McLaw and Jenkins kept the pressure on, one attacking head-on while the other attempted maneuvers to turn the Union flank, all to no avail. As darkness fell, the Union line held and the Confederates ceased their assaults. Burnside ordered his troops to march through the night farther east, into the defenses of Knoxville, arriving there by dawn on November 17.

The running battle produced a surprisingly small number of casualties for so many hours of contact—approximately 400 Union and 570 Confederate.

While Burnside had gone west to confront Longstreet, his remaining force had not been idle. Ten hilltop fortifications and miles of trench lines now ringed three-fourths of the city, the fourth side protected by the Holston River (now called the Tennessee River). The most prominent fortification was Fort Sanders, on the northwest corner of the defense belt and manned by about 440 troops with 12 artillery pieces. This strong fortification was surrounded by a dry ditch 12 feet wide and 8 feet deep, and the walls rose almost vertically 15 feet above the ditch. Although the designer, Poe, was worried that the hilltop post stuck too far forward of the main defensive belt and thus presented an inviting target to the oncoming Confederates, he relocated his cannon to be able to fire straight down the ditch and added a new type of defense feature.

Fort Sanders

Poe had his engineers string telegraph wire about 1 foot off the ground between stumps and stakes just outside the ditch, weaving a densely knotted pattern several feet wide that would slow down and break up the line of any attacking force. This “trip foot” is now a common military defense feature, and Knoxville is the first place it is known to have been used in battle. Longstreet brought his forces up close to the Knoxville defenses and then halted. Although the weather was turning bitterly cold and some of his barefoot soldiers were literally freezing, he decided to wait until reinforcements arrived to make his move. Scouting the Union defense line while he waited, Longstreet determined that the only spot he had a real chance of taking was Fort Sanders, sited atop a low hill but just 200 yards away from a thick tree line that would cover and conceal his troops.

Brigadier General Bushrod R. Johnson arrived with 2,600 men in Colonel John S. Fulton’s and Brigadier General Archibald Gracie’s brigades on the night of November 25, along with Brigadier General Danville Ledbetter, Bragg’s chief engineer for the Army of Tennessee, who scouted the Union emplacements along with Longstreet. Based primarily on Ledbetter’s assessment of the situation, Longstreet modified his plans and ordered the assault to begin just before dawn on Sunday, November 29. With his newly arrived reinforcements, the Confederate commander had nearly 20,000 troops at his disposal to counter the estimated 12,000 of Burnside’s force.

Today, April 14, 1882, I say, and honestly say, that I sincerely believe the combined forces of the whole Yankee nation could never have broken General Joseph E. Johnston’s line of battle, beginning at Rocky Face Ridge, and ending on the banks of the Chattahoochee.

—Corporal Sam Watkins of the Confederacy, in Co. Aytch

The night of November 28 was freezing cold, with a misty rain turning to ice and sleet as the hours wore on. Longstreet assigned three brigades to make up the assault force: Brigadier General Benjamin G. Humphreys’s Mississippi, Brigadier General Goode Bryan’s Georgia, and Colonel S. Z. Ruff’s (Wofford’s) Georgia, all of McLaw’s division. Brigadier General G. T. Anderson’s Georgia Brigade of Jenkins’s division was ordered to “demonstrate” at their left flank against the northernmost wall of the fort.

About 11 p.m. skirmishers were ordered forward to capture the Union rifle pits before the fort; this action also alerted the Union defenders that action was imminent. For the rest of the night, small firefights broke out between pickets and skirmishers of both sides, joined in occasionally by canister rounds from the fort. Longstreet’s assault troops lay on the frozen ground atop their guns, trying to keep them dry and catch a little sleep. Fires had been forbidden, as they were too close to the Union line, and the freezing drizzle undoubtedly made everyone miserably cold.

At the first sign of light on the eastern horizon, three signal guns of Alexander’s artillery fired arcing red flares that exploded over the fort. With this the mass of Confederate infantry sprang to their feet and charged the ramparts of the earthwork redoubt. Twelve guns of Alexander’s artillery fired as rapidly as possible for a few minutes and then ceased firing so as not to strike the onrushing infantry.

Poe’s trip wire broke up the mass charge, but in quick order the assault troops gathered themselves and rushed onward, firing as they went. In the confused darkness, under rifle and artillery canister fire from the fort and stumbling through the outer defenses, all three brigades accidentally merged into one mass, meeting at the northwest bastion of the earthwork fort. Their massed fire at that point caused the Union guns to go silent, leading Longstreet and Alexander alike to believe the fort’s defenses had already been reduced. Casualties to this point had been extremely light, and a massive wave of butternut-clad troops pushed into the ditchwork defenses.

No scaling ladders had been constructed, as the walls were not thought to be unusually steep, but both the reality of the construction and the ice-covered ground brought the assault to a sudden halt. As Union defenders stayed down, occasionally raising an unaimed rifle over the rampart to fire at the massed infantry, men formed human ladders to gain the heights, standing on each other’s shoulders and passing their fellow soldiers on up. As dawn slowly brought light to the fort, officers and color bearers began planting the Georgia and Mississippi battle flags on the parapet.

Ditchwork defenses at Fort Sanders

As the first Confederates gained the top of the walls, the Union troops inside opened fire with every gun available. Nearly as soon as a color bearer planted a flag, he was shot down, and officers lifting their swords to urge on their troops were equally swiftly gunned down. One after another the fallen bloodred “damned flags of the rebellion” were lifted up by an infantrymen and then fell as he, too, was gunned down by the determined Union infantry and artillery gunners. As the Confederate troops came too close to the Union line to fire their cannon, Lieutenant Samuel N. Benjamin, commander of Company E, 2nd U.S. Artillery, within the fort, had his men light the fuses of cannon shells and throw them over the walls like hand grenades, exploding more than 50 of the lethal devices in the very faces of the Confederates in the ditch.

As the full light of dawn revealed the hopelessness of taking even one bastion of the fort, Longstreet reluctantly recalled his troops. As the first wave was withdrawing, Anderson ordered his men forward, unaware that his attack had also been canceled. The scene repeated itself, with the Georgians thrown back with heavy losses after a 40-minute pitched fight atop the ramparts.

As Jenkins was preparing for yet a third assault, word came to Longstreet that Bragg had been decisively defeated at Chattanooga and his help was urgently needed in Dalton. The attempt to regain Knoxville came to a sudden end as Longstreet immediately pulled out of the battle and marched south.

Longstreet quickly learned that Rosecrans had sent Sherman with two full corps to break his siege of Knoxville and now stood between him and Bragg. Reluctantly he abandoned his plans to march into Georgia and turned up toward northeastern Tennessee, hoping that Sherman would pursue him there and relieve the pressure on Bragg’s Army of Tennessee. Sherman probably saw right through that idea and shortly returned to Chattanooga, leaving two divisions behind to reinforce Burnside should Longstreet backtrack and try again. Longstreet spent a miserable winter with the remains of his command in Greenville, Tennessee, and returned to General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia in the spring.

Left behind, atop, and around Fort Sanders were the bodies of 129 killed and many of the 458 wounded from Longstreet’s ill-conceived assault. Ruff, Colonel H. P. Thomas, and Colonel Kennon McElroy all lay dead on the parapet next to a number of their color bearers. Confederate losses for this entire campaign were 198 dead, 850 wounded, and 248 missing, with Burnside losing 92 dead, 393 wounded, and 207 missing.

With the full knowledge that in order to hold on to their commands and perhaps even their commissions, they must win the coming day’s battle, both General Rosecrans, Union Army of the Cumberland commander, and General Braxton Bragg, Confederate Army of Tennessee commander, sat on either side of a line of battle just west of Murfreesboro, Tennessee, on the night of December 30, 1862. Studying their maps and consulting with their cavalry scouts, both commanders came up with identical plans: Strike the enemy’s right flank at daylight.

Bragg hoped to rout the Union force, cut it off from a retreat route back to Nashville, and then batter it to pieces against the riverbanks. Rosecrans equally hoped to rout the Confederate force, cut it off from a retreat through Murfreesboro, and then defeat the scattered force in detail.

As the two great armies lay just yards apart in the cold darkness, knowing that the morning might bring their own “great gettin’ up day,” regimental bands began playing patriotic tunes in the hopes of bucking up the morale. Confederate bands played “Dixie,” which would be defiantly replied to by Union bands playing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Finally, after much catcalling across the lines and general amusement, both sides’ bands joined together to play the heart-wrenching “Home Sweet Home.” Blue-coated and butternut-clad troops joined in singing together, a chorus of tens of thousands plaintively wishing for home and hearth in the windy, rainy night. As the last notes faded away, both sides grew silent, waiting in the dark for the morning’s scheduled carnage.

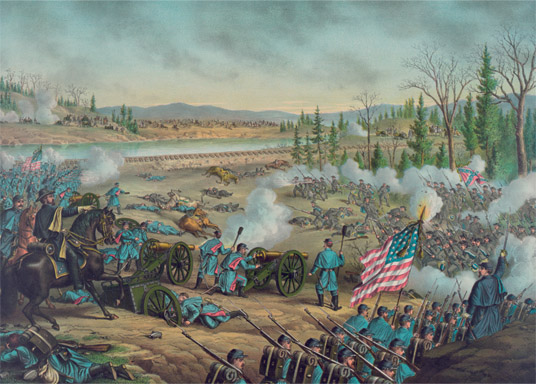

Battle of Stones River

Following his disastrous loss at Perryville during his aborted invasion of Kentucky in the fall of 1862, General Braxton Bragg retreated completely out of the state, falling back to Morristown in eastern Tennessee to try to resurrect his rebel army. Protecting the retreat was Brigadier General Joseph “Fighting Joe” Wheeler’s Cavalry Corps, who fought a running battle with the closely pursuing Union forces all the way to London, fighting no fewer than 26 engagements along the way. Bragg’s army moved into Knoxville on October 23, after a 200-plus-mile unbroken retreat march.

Bragg’s subordinates were outraged at his conduct during the campaign and considered him not only a poor commander but also a danger to the Confederate Army itself. One after another, Lieutenant General William Hardee, Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk, and Major General Edmund Kirby Smith all traveled to Richmond, Virginia, to demand Bragg’s removal, echoed by a host of politicians and influential civilians. After a short visit to the Confederate capital to prop up his status once again with his old friend, President Jefferson Davis, Bragg not only held on to his command but also received permission to move back into middle Tennessee and threaten Nashville.

Concentrating his forces near the small town of Murfreesboro, about 30 miles south of Union-held Nashville, Bragg allowed his great cavalry commanders, Morgan and Forrest, to roam throughout northern Tennessee and Kentucky. This disrupted Union commanders more than any concentration of infantry ever could hope to, with the Confederate cavaliers cutting supply lines, disrupting lines of communication, and destroying miles of rail lines and vital supply depots.

One such cavalry raid netted more than the usual: Morgan’s raid on Hartsville. In early December 1862, Colonel Absalom B. Moore’s 39th Brigade (Union Army of the Cumberland) was guarding the isolated river crossing at Hartsville, 40 miles northeast of Nashville. Under orders from Bragg to disrupt Rosecrans’s lines of supply and communication north of Nashville in the late fall of 1862, Morgan soon learned how isolated the small Union outpost was from any support and resolved to take it at once. Morgan’s force consisted of four regiments and one battalion of cavalry, two regiments of infantry, and one battery of artillery all told, with about 5,000 men. Moore’s force consisted of a single infantry brigade with about 2,000 men.

On the night of December 6–7, 1862, Morgan’s men crossed the Cumberland River near the Union encampments. Moore claimed in his report that they were wearing captured Union uniforms to fool the outer pickets. The inner line of picket guards sounded the alarm, and by 6:45 a.m. the fight was on. The outnumbered Union troops hastily formed a line of battle and briefly held their ground, while Morgan’s men surrounded the beleaguered command. Without hope of timely relief from other, much larger Union encampments only 9 miles away, Moore surrendered at 8:30 a.m.

Morgan immediately retreated south toward Bragg’s lines, taking with him some captured supplies, wagons, horses, mules, and about 1,800 prisoners. Union losses in the brief fight were 58 killed and 204 wounded, besides those taken prisoner. Morgan lost a total of 139 dead, wounded, and missing.

In response to the disaster in Kentucky, partly to quiet Bragg’s critics and partly to ease his own growing distrust of Bragg’s command strategies, Davis had ordered the reorganization of Bragg’s Army of Mississippi. His force was combined with Lieutenant General Edmund Kirby Smith’s Army of Kentucky and Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton’s Army of Mississippi (at Vicksburg), and Bragg was placed in charge of the new Army of Tennessee. Given overall command of the Department of the West was General Joseph Eggleston Johnston, technically then Bragg’s superior officer, but a man intensely despised by Davis and constantly overruled by him.

Johnston’s first act as the new theater commander was to recommend the abandonment of Vicksburg and the concentration of forces in Tennessee to overwhelm Rosecrans and cut off the flow of supplies to Grant’s army outside Vicksburg, which could be dealt with in a weakened condition later. The idea was to handle each Union army in turn with a united Confederate force, instead of trying to fight a two-, three-, or four-front war. Davis not only refused, but he also traveled to Bragg’s headquarters in Murfreesboro and personally ordered him to detach the 7,500 troops of Major General Carter Littlepage Stevenson’s division to reinforce Pemberton in Vicksburg. This cut nearly one-sixth of the fighting force out of Bragg’s command at a time and a place where action was imminent.

General Hood was in command of the Army of Tennessee at this time and if anything was ever out of all sorts it was the Army of Tennessee. Old Joseph E. Johnston looked after his men and did not run them into any unnecessary engagements. Hood would fight at the drop of the hat and drop it himself, so he thought he would show Sherman a few things out of the ordinary.

—Private Robert C. Carden, of the South’s

Company B, 16th Tennessee Infantry, about Lieutenant General John Bell Hood

Upon hearing of the action at Hartsville and other Confederate cavalry operations in west Tennessee and Kentucky, Rosecrans assumed that Bragg was now without scouts and therefore blind to any Union troop movements. From his own cavalry scouts, he had learned that the Confederates were at Murfreesboro preparing to go into camp for the winter, and he immediately issued orders for his army to march out and confront them. The North’s Army of the Cumberland moved southeast from Nashville on December 26 with roughly half the available troops, organized into three wings with a total of just over 44,000 men. Major General Thomas Leonidas Crittenden’s left wing moved straight down the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad tracks, while Major General Alexander McDowell McCook’s right and Major General George Henry Thomas’s center wings marched to his right down the McLensville Turnpike and part of the Franklin Turnpike.

Bragg had plenty of warning from both his scouts and Wheeler’s cavalry, still operating between his command and Nashville. He spread his forces out into a 32-mile-wide front from Triune through Murfreesboro itself to Readyville, covering any possible approach from the north. The ill-tempered Confederate commander had two corps at his disposal: Lieutenant General William J. Hardee’s corps on the left and Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk’s corps on the right. Wheeler’s cavalry both slowed down the Union advance and protected the army’s flanks; all told, about 32,000 men were available for combat.

Bragg’s scouts soon reported the exact approach route and composition of the Union force, and he pulled his troops into a tight semicircle just north and west of Murfreesboro, astride the West Fork of the Stones River. Ironically, Rosecrans himself was blind to the Confederate movements and strength, having sent his own cavalry north and west, chasing off after Forrest and Morgan. About 3 p.m. on December 29, without any warning, Crittenden’s corps made contact with the Confederate forces of Major General John Cabell Breckinridge’s 2nd Division (of Hardee’s corps) along the Stones River bank, northwest of Murfreesboro. A small skirmish erupted, ending shortly when both forces moved back a bit to await orders on how to proceed.

Troop positions on December 29, 1862

While Rosecrans hastily brought up the rest of his force to concentrate on what he believed, for some unknown reason, to be a Confederate force in full retreat, Wheeler sprang into action. Riding in a giant arc through the Union rear, he captured about 1,000 prisoners, burned more than a million dollars’ worth of ammunition and medical supplies, and caused a general panic that nearly turned into a rout back to Nashville.

Unprepared to immediately launch into battle against the strong Confederate position before him, Rosecrans hesitated through most of the day of December 30, finally meeting with his top lieutenants to hammer out a plan of action in the afternoon. Together they agreed that the Confederates’ weakest point was on the right of their line, where Breckinridge stood to the far north of the line of battle. While units were shifted north to prepare for an assault the next morning, McCook’s men were directed to light a large number of campfires on the far right of the Union line to fool their adversaries into thinking that units were being shifted for an attack coming from that angle, instead.

McCook’s wing was arrayed, from right to left, by Brigadier General Richard W. Johnson’s 2nd, Brigadier General Jefferson C. Davis’s 1st, and Brigadier General Philip H. Sheridan’s 3rd Divisions. In the center of the line was Brigadier General James S. Negley’s 2nd Division of Thomas’s wing, and on the left was Brigadier General John M. Palmer’s 2nd and Brigadier General Thomas J. Wood’s 1st Divisions of Crittenden’s wing, which extended the Union line all the way to the river. Two other divisions were in an assembly area behind the lines, readying for an assault scheduled for 7 a.m. on December 31. Rosecrans had passed orders down that his men were to finish their breakfast before the attack began.

All through the day of December 30, Bragg expected a Union assault on his lines and shifted his troops to better meet the Union formation. Late in the afternoon, noting the Union troop movements and fooled by the fake campfires, he was convinced that the main attack would come from that direction, onto his left flank. He ordered his troops to be shifted to meet the perceived threat and readied for his own attack on what he thought was the mass of enemy, on the Union right. The attack was to begin at first light, a little after 6 on the morning of December 31.

Corps Confusion

The Army of the Cumberland under Rosecrans was officially designated the XIV Corps (formerly Buell’s Army of the Ohio) on its creation on October 24, 1862. Although the army as a whole was far larger than the traditional corps, the true corps-level organizations under its command were designated “wings” instead. This confusing mess was finally rectified on January 9, 1863, when the wings were redesignated the XXI, XIV, and XX Corps.

Breckinridge stayed in position on the right, while the other two divisions of Hardee’s corps swung around to Polk’s left. The left of the Confederate line consisted of Major General John Porter McCown’s and Major General Patrick Ronayne Cleburne’s divisions of Hardee’s corps. The center consisted of Major General Jones Mitchell Wither’s division of Polk’s corps, with Major General Benjamin Franklin “Frank” Cheatham’s division just to the rear as a reserve. Brigadier General John A. Wharton’s Cavalry Brigade took up the far left flank of the Confederate line.

At 6:22 a.m. 4,400 butternut-clad and battle-hardened troops of McCown’s division stormed out of the gray, misty predawn twilight into the right of the Union line, catching totally by surprise the Northern soldiers leisurely eating breakfast, shaving, and getting dressed. Most of McCook’s regiments still had their weapons at stack arms and unloaded as they were routed or shot to pieces where they stood.

Cleburne’s division, advancing behind and in support of McCown’s, found itself alongside their fellow division in the front line, as the Union army hastily retreated to the north and west, dragging the Confederate assault behind them. As their assault slowed, mainly from the rough terrain and exhaustion, Cheatham’s division entered the attack and helped push the Union line farther north. Davis’s and Sheridan’s divisions managed to hastily assemble a sufficiently strong line of battle and put up a strong resistance that slowed the Confederate advance. About 9:30 a.m. Sheridan even managed to mount a limited counterattack, which pushed back Cheatham long enough to allow a more orderly retreat. By 10 a.m. the Union line was compacting into a strong position just west of and running parallel to the Nashville Pike.

Although the morning had gone very well for Bragg, casualties were appalling; Hardee and Polk had both lost about one-third of their men and were begging for reinforcements. Bragg had none to send.

The Union line had formed, “bending back their line, as one half-shuts a knife-blade,” according to Colonel David Urquhart of Bragg’s staff, with the sharp angle forming a salient in a four-acre patch of woods called the Round Forest, which the troops soon renamed “Hell’s Half-Acre.” Rosecrans ordered his remaining uncommitted units, originally tasked to assault the Confederate right, into this salient for a last-ditch defense. Brigadier General Horatio Philips Van Cleve’s 2nd and Brigadier General Thomas John Wood’s 1st Division got into position in the woods just in the nick of time.

Bragg ordered what he thought would be a final assault into the Union position in the small patch of woods, led by Brigadier General James Ronald Chalmers’s 2nd Mississippi Brigade. These men were some of the freshest available, having just spent the previous 48 hours lying in shallow trenches on the far right of the line, awaiting an attack that never came. One regiment, the 44th Mississippi, went into the assault with most of the men unarmed; their rifles had been collected up a few days earlier to distribute to units thought more in danger of attack, and just before going into the line of battle, they were reissued what the brigade ordnance officer declared as “refuse guns.” Most either could not be fired at all or had to be reassembled after each shot.

Chalmers’s brigade “moved forward in splendid style,” according to one of their opponents, Colonel Thomas Sedgewick of the 2nd (U.S.) Kentucky, but almost immediately began receiving murderous fire from the well-positioned 2nd Kentucky and 31st Indiana Regiments. The Confederates withered under the intense fire, but then recovered and closed to within 150 feet of the Union troops, where they exchanged fire for nearly 30 minutes before retreating with heavy losses. Chalmers himself was seriously wounded, and some regiments lost as many as eight color bearers in the brief assault.

As the last of Chalmers’s men retreated, at about 9:30 a.m., a brief lull fell over the fighting. Fresh Union regiments were brought into the salient, while another Confederate attack was organized. Brigadier General Daniel Smith Donelson led his Tennessee Brigade into the same sector about 10 a.m., this time successfully breaching the Union line to the right (west) of the Round Forest, taking prisoners and capturing some artillery pieces. As the Confederate attack successfully progressed, more and more units were fed into the line by commanders of both sides, both determined to take and hold this critical position.

The fierce battle for possession of the wooded salient raged on for more than two hours before the Confederates were forced to withdraw. “Appalling casualties” is hardly an apt description of what the Tennesseans endured; Colonel W. L. Moore’s 8th Tennessee Infantry Regiment, which had advanced far beyond any other unit, coming close to the turnpike itself, finally retreated, leaving behind 301 dead and wounded of the 440 troops it had advanced with, including Moore himself. This loss, 68 percent casualties, was the worst suffered by a Confederate regiment in any single battle of the entire war.

Getting to Stones River

Stones River Battlefield is in Murfreesboro, about 30 miles south of Nashville on I-24. Take exit 78B, which will connect you directly with US 96 East. Stay on this highway until the intersection with US 41/70, turn left (north) on US 41/70 to Thompson Lane (just a short distance north on the highway), and turn left (west) onto Thompson. Follow this road to the turnoff onto the Old Nashville Highway, and the plentiful signs in the area will take you into the battlefield proper.

After the battle, the Union troops stayed busy constructing one of the largest forts of the war, a 200-acre post surrounded by 14,000 feet of earthworks, soon named Fortress Rosecrans. Grateful men of Hazen’s brigade built a large memorial to him and their comrades lost in the vicious fight before leaving later in 1863; this is considered the oldest intact monument of the war.

Today most of the battlefield is taken up by the urban sprawl of rapidly growing Murfreesboro. A small portion of the original 4,000-acre battlefield is preserved and protected by the National Park Service, which also oversees the inclusive Stones River National Cemetery. Only Union soldiers (and veterans of subsequent wars) are buried here; more than 2,000 of the Confederate dead are buried in a mass grave at nearby Evergreen Cemetery. Only 159 of this number are known and so marked. The remainder of the Confederate dead were buried in unmarked, now-lost mass graves by Rosecrans’s men, who stayed in and around the battlefield for another five months.

With the failure of the morning assaults, the battlefield grew quiet for another few hours. At about 4 p.m. the last four Confederate brigades that had not yet seen action assaulted the Round Forest position once again. Brigadier General Daniel Weisiger Adams’s 1st and Brigadier General John K. Jackson’s brigades were repulsed with heavy losses. Colonel Joseph Benjamin Palmer’s and Brigadier General William Preston’s brigades were sent in for the same results.

With the attacks over for the day with the approaching darkness, the Confederates held most of the field, now covered with dead and wounded soldiers of both sides. Rosecrans considered withdrawing back to Nashville but decided to stay and attack again—that is, if his opponent Bragg did not. Bragg returned to his headquarters in Murfreesboro and, somehow convinced that his army had been totally successful in the assault, telegraphed Richmond that “God has granted us a happy New Year.”

Neither side attacked the next day, January 1, 1863, Rosecrans ordering his men to heavily entrench. Bragg took the quiet along the line, for some unknown reason, to indicate that the Union soldiers were on retreat back to Nashville. Wheeler’s and Wharton’s cavalry spent the day harassing the Union supply lines, with some moderate success. Bragg decided to assault the high ground to the left of the main Union line, hoping to find a place he could mount artillery and pour enfilading fire down on the rest of the Union line. Breckinridge was given the task of taking this position the next afternoon.

Breckinridge was horrified by his orders. Acting on his own, he had ordered a reconnaissance of the very area Bragg was proposing to attack. On his return from the dangerous scouting mission, Captain W. P. Bramblett of H Company, 4th Kentucky, the Orphan Brigade (so called because Kentucky was occupied by Union forces and the men could not go home until the war was over), had remarked that not only was this position already strongly held, but that more Union regiments were moving in, and it looked like “Rosecrans was … setting a trap” for Bragg to fall into.

Traveling to Bragg’s headquarters, the Kentuckian presented his findings and requested the attack be canceled or moved. Bragg, ever intractable when told his ideas were faulty, insisted that the attack go ahead as scheduled, and set the hour of assault for 4 p.m., one hour before the winter sun set. Breckinridge angrily returned to his command, proclaiming to some of Bragg’s staff officers that he was carrying out the attack under protest and fully expected it to fail.

As Breckinridge’s men moved slowly into position, word was passed to drop their packs (which infantrymen were loath to do, rightfully worried that a rapid retreat would mean the loss of their personal possessions) and prepare for a rapid assault. Hanson rode down his regiments forming up, stopping before each and ordering the regimental commander, “Colonel, the order is to load, fix bayonets and march through this brushwood. Then charge at double-quick to within a hundred yards of the enemy, deliver fire, and go at him with the bayonet.” As the men aligned themselves, a cold, wet sleet started coming down hard, numbing bare hands and feet and soaking what threadbare clothes they had left.

At exactly 4 p.m., a signal round went off from an artillery battery, and the assault force fixed bayonets and moved forward at the double-quick. Leading on the left was Brigadier General Roger Weightman Hanson’s 4th Brigade, with Brigadier General Gideon Johnson Pillow’s 2nd Brigade to his left, followed about 150 yards to the rear by Colonel Randall Lee Gibson’s 1st and Preston’s 3rd Brigades—all told, about 4,500 men.

The first 900 yards of the assault went well. Although almost immediately coming under fire from Union positions on the hilltop, Hanson’s and Pillow’s brigades advanced without seriously disturbing their formation, brushing aside the Union skirmishers in front of the main line of battle with hardly a casualty. Colonel Samuel Beatty Price’s 3rd Brigade of Van Cleve’s division, atop and just in front of the targeted hill, held their fire until the Confederates were nearly upon them.

With the onrushing Kentuckians only 60 yards away, Price ordered his command on their feet to fire a volley into the butternut-clad ranks. The men of the Orphan Brigade never slowed down. Returning their own volley, the men let out their weirdly high-pitched battle yell and charged the Union line, bayonets glistening in the late-afternoon rain and sleet. The Union troops fired one last ragged volley and then bugged out, leaving the hill to the assaulting Confederates. As Hanson’s men jumped over the abandoned Union breastworks, a Union artillery shell hit the general in his leg. Breckinridge, riding up to assess the success of his assaulting units, jumped off his horse and frantically tried to stop the bleeding, but to no avail. Although an ambulance soon arrived and Hanson was soon in the care of a surgeon, he died minutes later.

Storming over the hill and into the valley below, the Confederate assault continued unbroken to the east banks of Stones River itself. No doubt recalling how artillery had broken the Union ranks at Shiloh’s Hornets’ Nest a few months previous, Major John Mendenhall of the Union, Crittenden’s artillery officer, had hastily assembled every available artillery battery and positioned them on a rise overlooking the west bank of the river. Fifty-eight guns commanded the river approach with unobstructed fields of fire onto both banks. As the Confederates boiled out of the wood line and ran to the river, running over a small rise next to the riverbank, Mendenhall ordered his batteries to open fire.

The explosion of artillery shattered the Confederate assault. More than 100 shots per minute rained down on the assault force, blowing apart whole regiments in a matter of minutes. The attack almost instantly turned into a matter of holding what they had gained; within minutes it turned into just getting out alive. No order given, the Southern soldiers simply retreated as best they could, dragging behind them a counterattack that ended up regaining all the Union losses of the afternoon. Confederate losses amounted to more than 1,700 of the best men on the field, nearly half of what had started out.

His attacks muted, his offense stalled, and his ranks shattered, Bragg stayed on the field one more day without contact with the Union forces, and then quietly withdrew during the night of January 3 south of Murfreesboro to Shelbyville. Rosecrans’s force was too spent to pursue, staying in the area another five months before resuming any offensive operations. Neither side could really claim victory, both being mauled to the point where their armies were rendered nearly useless for many months, but Rosecrans’s army held the field at the end, and Bragg failed in his attempt to retake Nashville. Rosecrans lost a total of 12,906 dead, wounded, and missing; Bragg, a total of 11,740.

After Lincoln’s election and the parade of Southern states seceding from the Union, it was not at first thought that any grand scheme or strategy for defeating the strong Confederate armies would have to be devised. General Winfield Scott, aged commander in chief of all Union armies, suggested early on a plan that would cut off trade and supply to the South, effectively starving it into submission. This so-called Anaconda Plan was initially rejected by Northern politicians, who in the manner of politicians everywhere and throughout history, demanded a “quick ’n’ easy” solution to a complex and deadly problem. Their idea, which was unfortunately happily carried out by the army, was to simply march out and “show the grand old flag,” and the Southerners would run screaming from the field.

Southerners proved a bit more intractable than the Northern politicians had predicted. With the Union disaster at the First Manassas (First Bull Run to the Yankees), realization set in that this was not going to be any sort of “90-day war” and that a real, workable strategy would have to be adopted. Based on Scott’s plan, a three-part strategy was approved and adopted: first, a tight naval blockade of the entire Southern Atlantic and Gulf Coasts to cut off supplies and trade with foreign nations; second, an invasion of Virginia as soon as possible, with the goal of capturing the Confederate capital of Richmond; and third, the capture and control of the major river systems in the heartland of the Confederacy, the Mississippi, Cumberland, and Tennessee Rivers.

The naval blockade was effectively put into place on more than 3,500 miles of Southern coastline by July 1861, but Major General George Brinton McClellan’s feeble attempts to take Richmond proved much less successful. To carry out the third portion of the grand plan, Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant and Flag Officer Andrew Hull Foote (various sources list him as a captain, commodore, or admiral at this point in time) were given the mission of opening up the great Southern rivers to Union control. Together they decided to concentrate initially on taking control of the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers in northern Tennessee.

Joseph Eggleston Johnston

One of the most beloved of all Civil War generals, second only to Lee in this regard, Joseph Eggleston Johnston was born in Farmville, Virginia, in 1807 and was appointed to West Point in 1825. He graduated 13th in his class of 46 in 1829 and was initially assigned to the 4th Artillery, seeing service during the Blackhawk War, on the western frontier, and during the Seminole War in Florida. He resigned his commission in 1837 to work as a civil engineer in Florida, only to run into further combat situations with hostile Indians while working with John Wesley Powell’s expedition. Although seriously wounded in the head, Johnston rallied a defense and successfully moved the party to a safer area.

In 1838, partly in recognition of his exploits with Powell, Johnston was recommissioned in the engineering corps of the army and promoted to captain. He served under General Winfield Scott during the Mexican War, was wounded five times in combat, and led the final charge at Chapultepec.

Johnston resigned his U.S. Army commission on April 22, 1861, and was almost immediately commissioned as a major general of Virginia and brigadier general of the Confederacy (mixed commissions like this were common in the Confederacy). He commanded the combined Confederate forces at the opening major battle at Manassas and was subsequently one of four promoted to the highest rank of full general (along with Robert E. Lee, Albert Sydney Johnston, and Samuel Cooper). Johnston did have a personal fault of occasionally complaining about things of little consequence, and his comment that he should have been given seniority over Lee in this set of four, based on his rank and position in the prewar U.S. Army, served only to irritate President Jefferson Davis of the Confederacy, turning him into a lifelong enemy. Davis had several personal faults as well, and his thin skin and inability to stand criticism were his worst. Soon afterward, Johnston was seriously injured at the battle of Seven Pines and was relieved from duty. When he returned to service in November 1862, he was placed in charge of the newly formed Department of the West, theoretically in command over General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee and Lieutenant General John Clifford Pemberton’s Department of Mississippi, Tennessee, and East Louisiana, although he was given no support by Davis in having his orders and directives obeyed.

After Pemberton had lost Vicksburg and Bragg lost Tennessee, partly as a result of the conflicting orders given by Johnston and Davis, Bragg was relieved of command, promoted to military chief of staff, and replaced with Johnston in December 1863. There Johnston reversed a number of Bragg’s draconian rules and regulations, such as having men who stayed too long on leave shot for desertion, refusing to issue many leaves in the first place, issuing reduced rations when plenty were available, and requiring two and even three roll calls a day to catch anyone who might dare try to sneak away. Command of the Army of Tennessee was both Johnston’s finest hour and where his natural abilities flourished. He honestly loved and cared for his men, and they returned his love with a devotion that lasted to their own deathbeds. One of the privates in the ranks of his army, Sam Watkins of Columbia, Tennessee, had this to say about the day Johnston assumed command:

A new era had dawned; a new epoch had been dated. He passed through the ranks of the common soldier’s pride; he brought the manhood back to the private’s bosom; he changed the order of the roll-call, standing guard, drill, and such nonsense as that. The revolution was complete. He was loved, respected, admired; yea, almost worshipped by his troops. I do not believe there was a soldier in his army but would have gladly died for him. With him everything was his soldiers, and the newspapers, criticizing him at the time, said, “He would feed his soldiers if the country starved.”

We soon got proud; the blood of the old Cavaliers tingled in our veins. We did not feel that we were serfs and vagabonds. We felt that we had a home and a country worth fighting for, and, if need be, worth dying for. One regiment could whip an army, and did it, in every instance, before the command was taken from him in Atlanta.

Johnston rebuilt his army just in the nick of time to face an army twice his size under Sherman, invading northern Georgia in May of 1864. Johnston was a past master at the running defense, as Sherman was a master at maneuver warfare, and his first priority was maintaining his force. Starting with the battles around Dalton, Johnston slowly gave ground before Sherman’s juggernaut, making sure the Union armies bled heavily for every inch they gained. Whenever possible and prudent, the Confederate commander launched counterattacks, thinning the Union ranks at New Hope Church and Pickett’s Mill. In other places, he set up defenses so strong that the Union ranks bled nearly dry trying to take them, at Rocky Face Ridge, Resaca, and Kennesaw Mountain.

Although Johnston managed to keep his army intact and in fighting trim and lost not a single artillery piece in the long retreat from Dalton, criticism of him and his tactics reached a fever pitch after he pulled south of the Chattahoochee River, just outside Atlanta. Johnston’s plan all along had been to force a costly campaign on Sherman, then pull into the nearly impenetrable defenses of Atlanta and allow the Union force to batter itself to pieces there. However, President Davis’s enmity toward Johnston reached a breaking point as he pulled back to Atlanta, and Davis fired the beloved commander on July 17, replacing him with one of his own corps commanders, the fiery and ill-tempered Lieutenant General John Bell Hood. To paraphrase what Sam Watkins said so well, let us close the book on that sad chapter after Hood’s promotion; agonizing as it is to consider, suffice to say only that the once proud and able Army of Tennessee suffered the torture of misuse after misuse, before at last expiring on the ramparts around Nashville six months later. Sherman, incidentally, was delighted with the replacement, remarking that while Johnston was a dangerous foe, Hood was fairly predictable, and “I was never so nervous with him at my front.”

Johnston was reappointed command of the pitiful remnants of the Army of Tennessee on February 23, 1865, and ordered to resist Sherman’s march once again, this time in the Carolinas. Still more concerned about the lives of his men than the fate of the obviously doomed Confederacy, Johnston led them into only one more major battle, at Bentonville, North Carolina, on March 19. Reasonably successful in their first assault into the flanks of one of Sherman’s four columns, Johnston wisely retreated before his Union nemesis could gather his own forces and crush him. Johnston opened surrender talks with Sherman shortly thereafter, the talks becoming more urgent after word reached them of Lincoln’s assassination. Although Jefferson Davis, passing through the area on his flight from Richmond, rudely ordered Johnston to break contact with Sherman’s force and retreat south with him, the courtly general instead signed the surrender documents on April 26.

After the war, Johnston worked in the insurance business in Savannah and Richmond and then served two terms in Congress as a representative from Virginia. He and Sherman became close friends after the war, and Johnston served as one of his old Union nemesis’s pallbearers at his funeral. Going bareheaded during the ceremony, on a cold, misty day in 1891, Johnston developed pneumonia and died just weeks later. His aide had tried to get the aged general to at least wear a hat, but Johnston’s only reply was, “He [Sherman] would not wear one if he was in my place.”

Grant and Foote agreed to start their campaign on the Cumberland River at Fort Donelson, near the Tennessee-Kentucky border, which would open up a river corridor to Nashville. Foote had overseen the construction of a new class of navy craft specifically designed for such interservice operations, the ironclad riverboat. These boats were relatively small, 75 feet long and 50 feet wide on average, shallow-draft craft with protected midship paddle wheels for propulsion, ironclad either entirely or at least protecting the gun decks, with rectangular casements covered by sloping iron armor with a small opening for cannon.

Early on, most of these gunboats were simply modified civilian riverboats, with widely varying sizes and gun capacities. One carried only four 8-pounder guns, while others carried guns as heavy as 42 pounds and mounted as many as 12 guns. Foote commanded three unarmed boats and four ironclads in the opening battles, manned by a rather motley assortment of 500 sailors who were formerly riverboat crewmen, Maine lumber-boat sailors, New England whalers, New York ferrymen, and some only described as “Philadelphia sea-lawyers.”

On the army side, Grant had about 15,000 soldiers organized into two divisions with five brigades. Brigadier General Charles Ferguson Smith took charge of three brigades, while Brigadier General John Alexander McClernand had two brigades under his command.

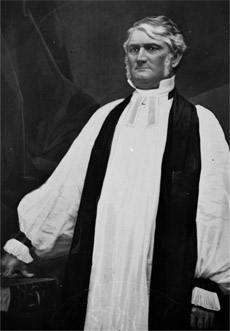

Major General Leonidas Polk, photographed in his bishop’s robes

In overall charge of the South’s defense of the Mississippi River and its approaches was Major General Leonidas Polk, an Episcopalian bishop who was quite frankly more at home in the ministry than the military. He was convinced that the main Union attack would move down the Mississippi and accordingly placed most of his men and material in the buildup of fortifications at Columbus, Kentucky, for the defense of Memphis. He refused several requests for manpower and supplies to build up defenses on the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, believing that these were “backwater accesses with no real strategic value.”

Cover of sheet music for a patriotic song dedicated to Lincoln’s secretary of the navy, Gideon Welles, in which Uncle Sam rides a “ram,” or ironclad steam vessel, down the Mississippi River.

Governor Isham G. Harris of Tennessee, more concerned about the loss of the middle of his state than Polk was, personally ordered General Daniel S. Donelson of the Confederate Army to construct fortifications on these two rivers at the Kentucky border, where they are only 12 miles apart. Donelson chose a very poor site for the post guarding the Tennessee River; later named Fort Henry, it was placed on a floodplain that frequently flooded and was commanded by high ground across the river. The Cumberland River post was much better; later named Fort Donelson in his honor, the earthwork fort consisted of 2½ miles of fortifications surrounding two heavily entrenched artillery emplacements atop a 70-foot bluff overlooking the river.

The right of revolution is an inherent one. When people are oppressed by their government, it is a natural right they enjoy to relieve themselves of this oppression, if they are strong enough, whether by withdrawal from it, or by overthrowing it and substituting a government more acceptable.

—Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, Union Army, from his memoirs

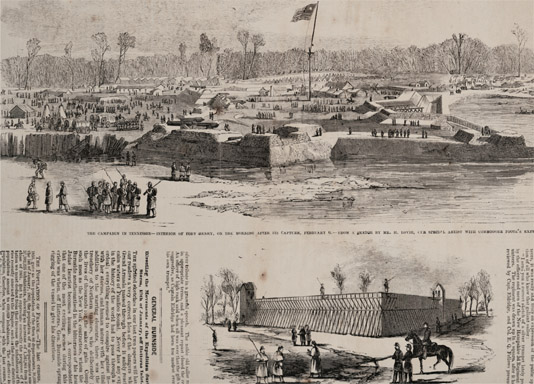

Interior of Fort Henry on the morning after its capture, from a sketch by H. Lovie, artist with Commodore Foote’s expedition

Grant and Foote agreed to start their campaign by capturing Fort Henry. Foote started up the Tennessee River with his seven gunboats closely followed by Grant’s force loaded on transport barges. Grant’s plan was to land his force on either side of the fort, to prevent escape of the garrison, and march overland toward an assault while Foote’s gunboats weakened the Confederate defenses by continuous bombardment.

Inside Fort Henry, things were getting soggy. The river was flooding again, and water was standing 2 feet deep in parts of the fort. Brigadier General Lloyd Tilghman, post commander, was disgusted; calling the fort’s condition “wretched,” he sent most of the 2,500-man garrison to nearby Fort Donelson and kept only a single 60-man artillery company to man the 17 guns.

On February 6, 1862, with Grant’s troops landed and on their way over muddy, flooded roads, Foote sailed his gunboats nearly to the ramparts of the fort and opened fire. With the fort continuing to flood, Tilghman’s gunners returned a telling fire, disabling two gunboats and killing or wounding nearly two score of their crew. The fort’s crew fared little better, with four guns flooded out or disabled by enemy fire and 20 men killed or wounded. After less than two hours of bombardment, Tilghman surrendered his post before Grant had a chance to close in. The fort was so flooded by that point that the Union officers accepting the surrender floated in the main gate by boat. Lost in the brief confrontation were 11 killed, 31 wounded, and 5 missing for the Union force; Tilghman reported his losses at 20 killed or wounded and the rest made prisoner.

The day after the fall of Fort Henry, the commander of the Western Theater, General Albert Sydney Johnston, ordered the abandonment of Columbus and Bowling Green, Kentucky, and the movement of most of his armies south of the Cumberland River. To facilitate this movement and make safe his new positions, he ordered that Fort Donelson be reinforced and held.

Battle of Fort Donelson

Fort Donelson originally held a garrison of 5,000 troops, soon reinforced to a total of 18,000 (as few as 12,000 by some accounts) but burdened with a weird command structure where three generals shared the responsibility: Brigadier General John Buchanan Floyd, Brigadier General Gideon Pillow, and Brigadier General Simon Bolivar Buckner. To add to the unworkable situation of having three commanders, Buckner and Pillow were bitter political enemies back home in Kentucky; Pillow was a lawyer with no formal military training and a bad case of arrogance; Buckner was the only professional soldier of the three; and Floyd was a weak-willed politician who had been Buchanan’s secretary of war. Floyd took over as senior commander strictly by virtue of his earlier date of commission.

While you were eating your good dinner we soldiers would have been glad to have the crumbs that fell from your table. I will tell you what our meals were this day: Breakfast, rice and beef. Dinner, rice. Supper, beef and rice. Rice is our favorite dish now.

—William Henry, 101st Illinois Infantry Regiment of the Union Army

Grant waited several days before marching on Fort Donelson, building up his forces to as many as 27,000, with about 15,000 ready for an immediate investment of the Confederate stronghold. On the afternoon of February 13, the Union troops were in position to the south and west of the fort, with Foote on the way upriver with his gunboats and more troops to land on the north side of the fort. The day was clear and sunny, with quite a warm temperature for a winter’s day, leading many of the Union soldiers to ditch their heavy overcoats by the side of the road as they marched in.

The night of February 13 a winter storm blew in, dropping the temperature down to 10 degrees and setting off a raging blizzard on the unprotected troops. Campfires had been forbidden, as any light brought a barrage from Fort Donelson’s guns. A brief skirmish earlier in the day had resulted in numerous Union wounded, many of whom froze to death during the long night.

Late in the afternoon of February 14, Foote arrived and swung into action. His four heavily armored gunboats closed to within 400 yards of the fort, exchanging heavy fire with the Confederate artillery crews until darkness set in. Foote was decisively defeated, his gunboats raked with heavy cannon fire until rendered useless, and most of his sailors aboard killed or wounded. Foote himself was seriously injured aboard his flagship, the St. Louis, ultimately dying 16 months later of complications caused by the wound.

Getting to Forts Henry and Donelson

Forts Henry and Donelson were located quite close to each other in an area of Tennessee now known as the Land Between the Lakes (or simply LBL to the locals). To get there from Clarksville, which is located just off I-24 northwest of Nashville, take US 79 for about 40 miles. Fort Donelson National Military Park, directly on US 79, is 3 miles west of the small town of Dover. The site of Fort Henry is on, appropriately, Fort Henry Road, about 6 miles farther west on US 79.

Time and river floods have rendered invisible the ramparts of Fort Henry, now indicated only by a single historic marker and a hiking trail around the riverbank area. There are no amenities, restaurants, motels, or basically anything else at this location. The nearest town of any size is Dover, roughly 10 miles east on US 79.

Some of Fort Donelson has been preserved and protected by the federal government, which also located a National Cemetery at the site. The Cumberland River is no longer recognizable from its Civil War days, having been dammed up to form Lake Barkley. Very little survives today from the Civil War period, the local attraction being the massive Land Between the Lakes recreation area, toward which most of the few local businesses are oriented.

Although the Confederate force had been quite successful resisting the waterborne assault, it was obvious that they would not be able to make much of a stand against Grant’s land-based assault, sure to come in the following days. The three generals agreed to break out toward the east and rejoin the rest of Johnston’s force in Nashville. Launching a strong attack on the Union lines across the Nashville Road at daybreak, Pillow and Buckner managed to force the road open by noon. Unbelievably, though, Pillow ordered a retreat back into the fort on hearing a report that the Union troops in the area might be receiving reinforcements. Floyd, still in the fort, supported Pillow, and all the Southern soldiers who had forced the breakout were smartly marched back into the besieged garrison.

Pillow later claimed that he ordered the return to the fort because of a “confusion over orders,” stating that he thought the men were to go back, pack their belongings, and presumably tidy up the place before leaving. Once back in the fort, he insisted that his men needed food and rest before embarking on such a long march, and Floyd timidly backed him up against the violently agitated Buckner, who rightfully insisted they had to leave immediately for any hope of escaping the Union envelopment. As they stood arguing, Grant launched his own attack.

Correctly assessing that as the attack had come from the Confederate left, their right must be weaker, he ordered an assault on that part of their line. General Charles Ferguson Smith led his division in a strong assault against the Confederate trench lines, now held only by a single regiment of infantry. Buckner immediately moved his men back to counterattack, but Smith was able to capture and hold the outer line of defenses on that side of the fort before darkness brought an end to the day’s fighting.

The three Confederate generals again conferred, Pillow and Floyd in a sheer panic at their own capture and Buckner disgusted with their amateurish attempts at command. Floyd passed command of the post to Pillow, who immediately passed it to Buckner, who had made it clear that the only choice available was surrender. As Buckner made ready to end his resistance, Floyd and Pillow commandeered a steamboat and got themselves to safety across the river, along with a few hundred soldiers of Floyd’s command. Newly appointed cavalry officer Lieutenant Colonel Nathan Bedford Forrest, disgusted with Buckner’s intention to surrender, received his permission to escape through the surrounding swamps with as many men as possible.

On the morning of February 16, Buckner sent a message across to Grant asking for his surrender terms. Grant replied in a famous message, “No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender” (from which his nickname “Unconditional Surrender” came). Meeting at the Dover Inn later that afternoon, Buckner surrendered his command and the post. Casually discussing the action later with his prewar friend Grant, Buckner mentioned that he must have been disappointed not to have captured Pillow and Floyd as well. Well aware of Pillow’s alleged “abilities” as a battlefield commander, Grant remarked that had he captured Pillow, he would have immediately released him, as Pillow was more a danger to the Confederacy than an asset!

Numbers of those engaged, casualties, and prisoners vary wildly from source to source, but somewhere in the neighborhood of 27,000 Union and 21,000 Confederate troops were involved in the action, with Grant losing about 2,800 dead, wounded, or missing. The Confederate force lost about 2,000 dead or wounded and had about 14,500 made prisoner, the rest escaping with Forrest or bugging out on their own.

Confederate soldiers searching for the wounded by torchlight after the capture of Fort Donelson

Confederate Memorial Hall

3148 Kingston Pike

Knoxville, TN

(865) 522-2371

Formerly known as Bleak House, for the Charles Dickens novel, this slave-built brick house was constructed in 1858 and was used as Longstreet’s and McLaw’s headquarters during the brief siege operation. The tower was used as a sniper post during the Confederate operations; Brigadier General William Price Sanders of the Union’s Army, the fort’s namesake, was killed by a shot from this tower while standing on the lawn of the still-existent Second Presbyterian Church on November 16, 1862. The house was damaged by Union artillery fire and reportedly still has bullets embedded in the walls.

The house is now owned by the United Daughters of the Confederacy and is preserved and open to the public as a museum, with many period furnishings and decorations. It is open Wed, Thurs, and Fri. The last tour begins at 3:15 p.m. Group rates are available. The house is closed the entire month of Jan. The house has a gift shop that contains books about the history of the house as well as other educational items.

Fort Donelson National Battlefield

US 79 West

Dover, TN

(931) 232-5348, ext. 0

This 90-acre park features a small museum with a small collection of artifacts, as well as a 15-minute film about Grant’s river campaign. Occasional ranger-led demonstrations of rifle and cannon firing are presented, mainly in the summer months, and brochures for a self-guided driving tour are available at the information desk. Several emplacements and river batteries are well preserved and give a good feel for what it was like here during the siege.

Don’t miss the Confederate monument, which is rumored to be placed over a mass grave of Southern dead. After the fight, hastily buried Union dead were reinterred in what became a National Cemetery on the property, while the mass graves of Confederates were left undisturbed. As they were never marked, these final resting places lie scattered about the property, forgotten and lost. The National Cemetery contains 655 Union dead, only 151 of which are known. Soldiers from later wars are laid here as well, swelling the population to about 1,500.

Admission is free, but donations are accepted and strongly encouraged.

The Museum of East Tennessee History

601 S. Gay St.

Knoxville, TN

(865) 215-8824

This nicely laid out museum in the 1870s-era U.S. Post Office building displays a collection concentrating on the general history of the Knoxville area. There is a new permanent exhibit, Voices of the Land: The People of East Tennessee, with a Civil War section that includes a well-presented collection of uniforms and weapons. Admission is free for all on Sun.

Oaklands Historic House Museum

900 North Maney Ave.

Murfreesboro, TN

(615) 893-0022

Once the center of a 1,500-acre plantation, Oaklands was built in 1815 and is the best preserved of several existing antebellum mansions in the area. The plantation was the site of both the surrender of Murfreesboro to Forrest on July 13, 1862, and where President Jefferson Davis stayed when he visited the troops in December of the same year.

The house has been restored to its early Civil War splendor, with a beautiful sweeping main staircase and intricate fleur-de-lis wallpaper.

Stones River National Battlefield

3501 Old Nashville Hwy.

Murfreesboro, TN

(615) 478-1035

The 450-acre park includes only the portion of the battlefield involved in the first Confederate assault on December 31 and a section to the east close to the Round Forest area. The visitor center has a small but nicely presented collection of battlefield artifacts and a nine-minute orientation film about the battle, as well as a very nicely stocked bookstore. A self-guided driving tour audiotape is available (and recommended), as well as limited information about portions of the battlefield not on the property. Admission is free, but please do leave a donation in the box at the visitor center entrance. During summer, ranger-led tours are offered, as well as occasional living-history exhibitions.

Knoxville has a good selection of both independent and chain hotels and motels, as well as a sprinkling of bed-and-breakfast inns. For a complete listing and current information on local festivals and events, contact the Knoxville Tourism and Sports Corporation, (865) 523-7263, www.knoxville.org.

| Maplehurst Inn Bed and Breakfast | $$–$$$ |

800 W. Hill Ave.

Knoxville, TN

(865) 523-7773

(800) 451-1562

This small inn has one big advantage: It is very close to the Civil War sites at the University of Tennessee campus. Eleven rooms and a penthouse are available. They all feature cable TV with movies, and some have Jacuzzis. The adjoining restaurant serves breakfast only.

Murfreesboro is a fair-size city, with plenty of food and lodging choices. For a complete listing, as well as information on local events, contact the Rutherford County Chamber of Commerce at (615) 893-6565 or (800) 716-7560; www.rutherfordchamber.org.

| Carriage Lane Inn Bed and Breakfast | $$–$$$ |

337 E. Burton St.

Murfreesboro, TN

(615) 890-3630

(800) 357-2827

This inn is a collection of properties, all with private bath and elegantly appointed furnishings. It sits on what used to be the carriage lane to the Maney family home, which is now Oakland Historic House Museum. Historic sites, antiques shopping, and restaurants are all within walking distance.

| Doubletree Murfreesboro | $$–$$$ |

1850 Old Fort Pkwy.

Murfreesboro, TN

(615) 895-5555

(800) 222-8733

www.murfreesboro.doubletree.com

A beautiful, open, and spacious hotel, with a nicely laid out and decorated atrium lobby and 168 rooms and suites. A fitness center, restaurant, bar, and pool are on the property.

| Copper Cellar Cumberland | $$–$$$ |

1807 Cumberland Ave.

Knoxville, TN

(865) 673-3411

Close to the university campus, this high-end establishment specializes in steak and prime rib plus fresh fish and seafood dishes. Portions are huge, as are the desserts, and the best thing is that you most decidedly will not go away hungry. No dress code is posted or apparently enforced, but this is not a blue jeans sort of place. Lunch is crowded, with a lot of corporate suits present; supper seems a bit more relaxed.

| Patrick Sullivan’s Steakhouse & Saloon | $$–$$$ |

100 N. Central Ave.

Knoxville, TN

(865) 637-4255

This well-appointed tavern, built in 1888, is an upscale eatery in the best sense of the word, serving chicken, pork, fish, and pasta dishes prepared in several unusual ways. Some of the current menu choices are pan-seared pepper steak, prime Colorado beef, jumbo shrimp, and a tasty pasta creation. The burgers and blue plate specials are widely acclaimed. Thanks to the wooden floors and bare brick walls, the noise level can be quite high; there is a balcony level usually available where the seating is a bit quieter. Hours can fluctuate, so call ahead.

| Demo’s Restaurant | $$ |

1115 N.W. Broad St.

Murfreesboro, TN

(615) 895-3701

A local favorite, Demo’s specializes in spaghetti dishes and offers several varieties of other pastas, steaks, and seafood and a few Mexican dishes. The dining room is nicely decorated in dark green, with period-style lighting fixtures.

There are no facilities worthy of mention in the immediate vicinity of Forts Henry or Donelson, as this is a rather rural section of the state that attracts very few tourists. The nearest town with adequate facilities is Clarksville to the east. There you will find the usual array of chain fast-food and mid-range restaurants, as well as a selection of chain motels, mostly clustered around US 41 on the north side of town. Nearby Fort Campbell drives the local economy here, which leans heavily toward the sort of businesses young soldiers support, especially north of town to the Kentucky border. (Fort Campbell is actually in both states, and the entrance gates sit on either side of the state line.)