Chickamauga: The Rock and the Angel of Death

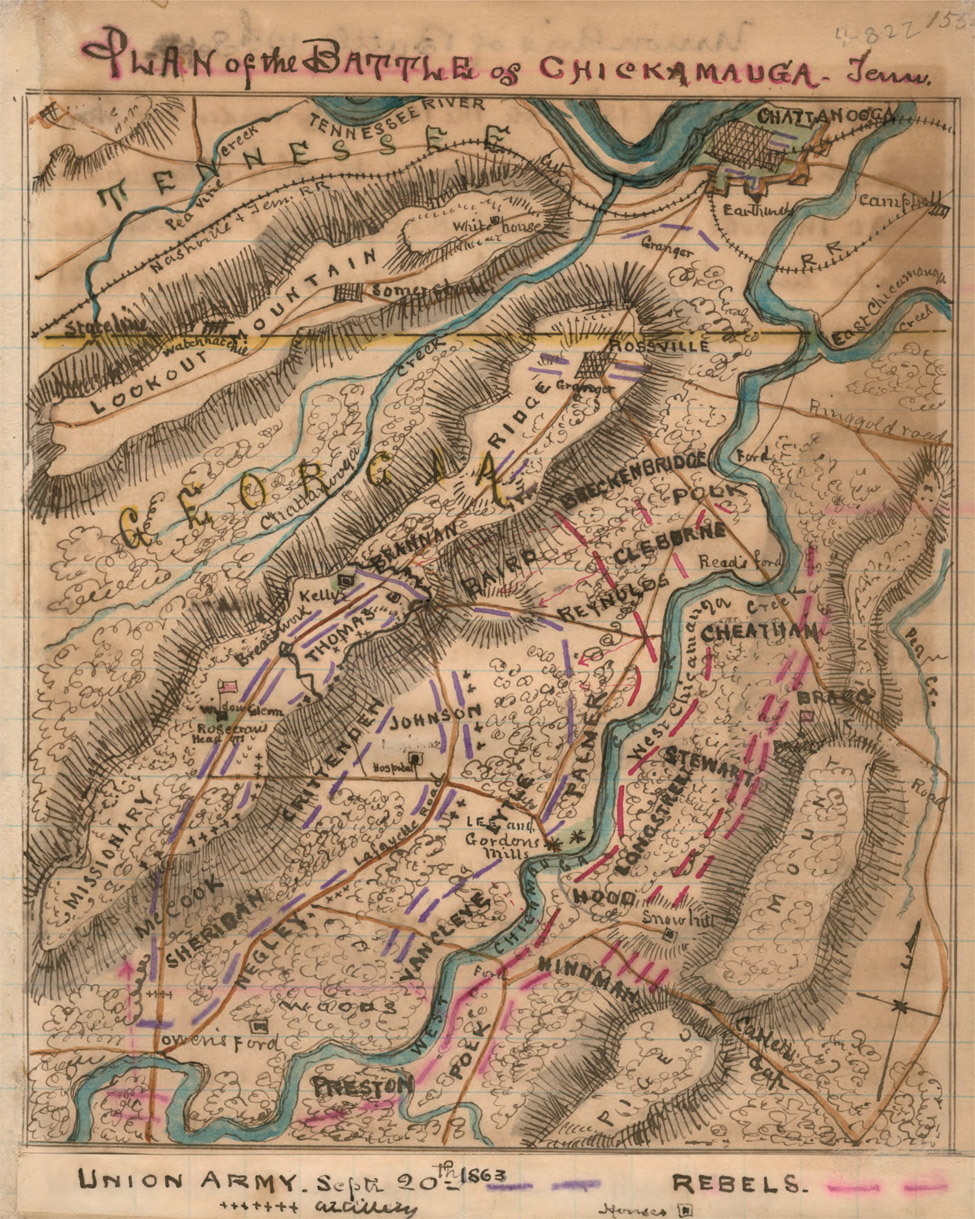

Map of the Battle of Chickamauga

Following an unsuccessful campaign in Kentucky and failure to push back Major General William Starke Rosecrans’s Union Army of the Cumberland at Stones River, Tennessee, in January 1863, General Braxton Bragg withdrew his still-intact Army of Tennessee back to Tullahoma to attempt a stand. Charged with protecting the vital transportation center of Chattanooga, Bragg intended to let Rosecrans bleed his army to death in frontal assaults on the Confederate position along the Duck River rather than trying another offensive himself.

Months went by without action. Rosecrans had nearly wrecked his own army at Stones River and needed time to refit. Finally, under pressure from President Abraham Lincoln, the Army of the Cumberland moved south, bursting through multiple gaps south of Tullahoma on June 24 and taking Bragg completely by surprise. His own line of retreat in danger of being cut off, Bragg hastily withdrew his entire force into Chattanooga with barely a shot being fired.

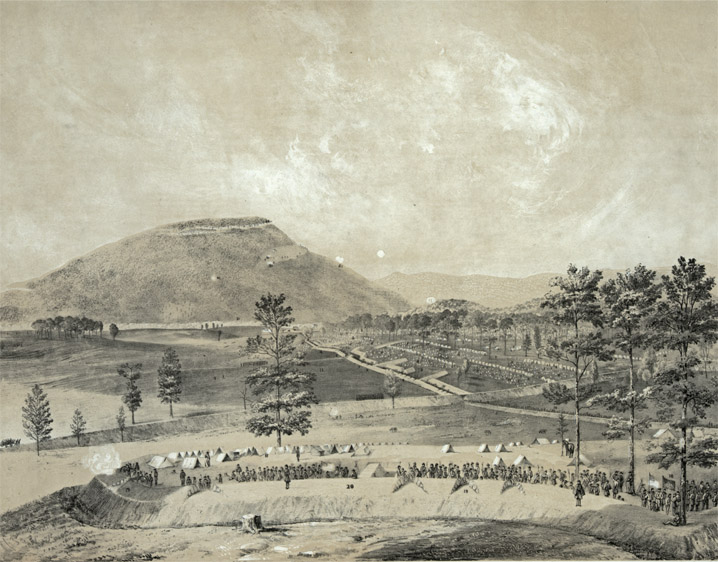

Army of the Cumberland in front of Chattanooga

Bragg had no idea of the actual position of the advancing Union columns. Believing that they still intended to envelop Chattanooga somewhere to the east from Knoxville, he spent several days fretting and giving conflicting orders. The Confederates reestablished their lines in the small mountain town by the Tennessee River, but when Union forces crossed unopposed at three points below the city, the Confederates again were ordered to withdraw south without a fight—this time completely out of Tennessee and on to the northwest Georgia town of LaFayette. Without a firm grasp of the situation and in a nervous frustration over what to do about it, Bragg missed several excellent opportunities to strike the separate Union columns as they exited the Lookout Mountain passes. On September 9, as the last of Bragg’s army left, the vanguard of Rosecrans’s entered the city from the north.

At about the same time, Major General Ambrose Burnside’s Army of the Ohio divided into four columns with 24,000 men and forced the Confederate garrison at Knoxville to abandon the city, again without a major fight. These forces joined Bragg’s column in the general retreat south into Georgia. The Confederate commander was determined to protect the vital industrial center of Atlanta and to regain control of Chattanooga if possible, so he tried an interesting tactic to draw Rosecrans’s forces into battle on his own terms.

Paying too much attention to planted “deserters,” who convinced Rosecrans that Bragg was in full, panicked retreat, the Union commander placed his 60,000-man force in three widely separated columns in order to cut him off and force the Confederate Army into battle, where it could be destroyed once and for all. One column led by Major General Thomas L. Crittenden passed through Chattanooga and went on to Ringgold, Georgia. Another, led by Major General George H. Thomas, passed through Bridgeport, Alabama, and with some difficulty crossed Sand Mountain to approach LaFayette. The third column, led by Major General Alexander McDowell McCook, went another 40 miles to the southwest of Chattanooga through northern Alabama toward Summerville, Georgia.

As the Union forces moved to his north and west, Bragg sent urgent requests for reinforcements and gathered his forces for battle.

Bragg knew that to protect Atlanta, retake Chattanooga, or even hold on for long in the north Georgia mountains, he would need reinforcements, plentiful and soon. In addition to the men from the Knoxville garrison, two divisions were sent from Major General Joseph Eggleston Johnston’s army in Mississippi. General Robert E. Lee agreed, reluctantly, to allow Lieutenant General James Longstreet to go to Bragg’s aid with two divisions of his corps (the third, Major General George E. Pickett’s division, was still combat ineffective after Gettysburg). All these reinforcements would bring the Confederate force to a higher available manpower than the Union’s, an exceedingly rare event at any point during the war.

With help on the way, Bragg became impatient to go into offensive action. Between September 10 and 13, with Rosecrans’s forces widely separated and cut off from mutual support, Bragg grabbed the tactical advantage and ordered divisional-size attacks at several points. Mysteriously, not a single attack was carried out; each divisional commander found one reason or another not to assault. Rosecrans shortly received word from spies and scouts about both the fizzled attacks and the incoming reinforcements and ordered his columns to pull together just west of Chickamauga Creek. By September 17 the columns were in close proximity, and Rosecrans ordered them forward to concentrate in the vicinity of Lee and Gordon’s Mill on Chickamauga Creek.

On that same day, Bragg’s forces were in place from near Reed’s Bridge over Chickamauga Creek in the north to opposite Lee and Gordon’s Mill in the south. With the leading elements of Longstreet’s corps just arriving by train and still a few hours’ march away, the order for attack was given. Bragg’s strategy was to sweep forward and take control of the LaFayette road, hitting the Union forces from the east, cutting them off from a line of retreat back into Chattanooga, and hopefully driving them back toward Alabama. Brigadier General Bushrod R. Johnson’s brigade was ordered to start the offensive by seizing and crossing Reed’s Bridge, followed by movement forward all along the nearly 5-mile line.

Confederate artillery opens fire on Union calvary on September 18, 1863, near Reeds Bridge.

Johnson moved forward early on the morning of September 18, but his and the other brigades’ advances were slowed by a combination of bad roads and miscommunication. Colonel Robert Minty’s 1st Brigade (2nd Cavalry Division) made the first contact with the advancing Confederate force, skirmishing about a mile east of Reed’s Bridge before being pushed back to the creek itself. Before withdrawing, Minty ordered the bridge burned, further delaying the Confederate assault. Johnson’s men did not actually cross the creek until late in the afternoon. By that time the leading element of Longstreet’s corps, Major General John Bell Hood’s division, arrived and took command of the column.

Just to the south at Alexander’s Bridge, another contact was made at about 10 a.m. between Colonel John T. Wilder’s 1st Brigade (Mounted Infantry, 4th Division, XIV Corps), supported by the 18th Indiana Artillery, and Brigadier General St. John R. Liddell’s Confederate division. Holding the line for most of the day, Wilder was forced to withdraw at about 5 p.m. when his right flank was turned by newly arriving elements of Major General William H. T. Walker’s corps, who had crossed the creek farther downstream. Pulling back toward Lee and Gordon’s Mill, Wilder was soon reinforced and managed to halt the sputtering Confederate advance after a fierce night attack.

On Saturday morning, after a long night of shifting his forces about to meet the developing Confederate threat, Thomas’s XIV Corps arrived at Kelley’s field on the LaFayette road, and he ordered Brigadier General John M. Brannon’s 3rd Division eastward to make contact with the Confederate force. About 7:30 a.m. they suddenly encountered dismounted troops in the vicinity of Jay’s Mill and both sides opened fire. There was no opportunity for either side to get organized, and the fight rapidly turned into a confused melee, with men firing every which way and seeking whatever cover they could in the surrounding forest. A few minutes into the fight, none other than Brigadier General Nathan Bedford Forrest himself came charging up, pistol in one hand, saber in the other, and began bellowing orders. The dismounted troops were part of his cavalry corps, detailed to protect the northern flank of the Confederate lines. Quickly, his men got into line, lying down in the damp grass side by side and returning a disciplined fire into the Union ranks. Casualties were high, nonetheless, for the legendary cavalry commander, who lost almost 25 percent of his men in the first hour alone.

Both Forrest and Brannon quickly called for reinforcements, and shortly Colonel John M. Connell’s 1st and Colonel Ferdinand Van Derveer’s 3rd Brigades (of Brannon’s 3rd Division) arrived to shore up the Union line, while Walker and Liddell brought their divisions to Forrest’s aid. The fight grew almost by itself; very soon additional units began pouring into the rapidly growing battle, extending the lines a few hundred yards to each side, then a half-mile, a mile, and then finally a nearly 4-mile-wide solid front of combat existed over the fields and forest from near Lee and Gordon’s Mill all the way up to well north of Jay’s Mill. Throughout the early afternoon, assault after assault pushed one side back a bit, then the other, neither side gaining any real ground or advantage. Both lines were in close contact the entire time, with appallingly high casualties piling up by the minute.

From that point on through the end of the day the battle was a “soldier’s fight,” as the thick woods and disordered array of combat units made it nearly impossible for commanders on either side to make informed tactical decisions. Both lines overlapped at several points, and hand-to-hand combat was commonplace across the fields.

Starting a little after noon, Thomas began shifting his forces north to oppose Confederate forces coming on line against his left flank. This opened up a hole in the main Union line that was quickly exploited by three brigades of Major General Alexander Stewart’s division. Attacking straight across the LaFayette road at the Brotherton farm, they succeeded in breaking the thin Union line. Following his lead, just to the left at the nearby Viniard Field, brigadier generals Jerome B. Roberton’s and Henry L. Benning’s brigades (of Hood’s division) stormed across the LaFayette road and pushed the Union forces out of their entrenchments and back about 200 yards.

Ghost Stories

It doesn’t take much traveling about in Civil War history circles until you start encountering ghost stories. Nearly as ubiquitous as tinny renditions of “Dixie,” rebel flags, and poorly made “authentic” kepis, ghost stories are sort of a peripheral industry in and of themselves, with pricey ghost tours, books, and hallowed traditions of sightings, usually in places that were peripheral to the war itself. The litany of the tour guide is often the giveaway that a “real” story from somewhere else has been borrowed to spice things up: “… and here in the window of this upstairs bedroom, the ghostly image of Sally Jane Beauregard is often seen at midnight on the third of the month during a full moon, staring out down the lane as if pining away for her lover who left, never to return …” We have often wondered what would happen if Sally Jane Beauregard really did show up one night.

Despite all the crass commercialization of the supernatural in certain areas, there seems to be a widespread and firmly held belief that something not of the flesh is present in any number of places—throughout our travels over the years, we have had all sorts of sober, serious historians, park rangers, and reenactors broach the subject with us without prompting, telling us of sights, sounds, and even smells they have experienced in the places blood was shed. Author John McKay admitted to a rather eerie encounter while a young soldier at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, in the 1970s. He saw what appeared to be a group of horsemen carrying a battle flag and crossing the road about a quarter-mile ahead of his jeep; they disappeared from sight in a large empty field on the other side.

A few places seem obvious to have encounters of this sort—the battlefield at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, has produced enough sightings to fill two books on that subject alone, and nearly the entire ranger staff at Andersonville National Historic Site had at least one or two stories of encounters to relate. Rangers and even some visitors at Shiloh had some stories, most of which seemed to circulate around the Bloody Pond section of the battlefield. One volunteer at the Castillo de San Marcos National Monument in St. Augustine (known as Fort Marion during the war) told a hilarious tale about the layers of “haints” around the 17th-century castle, where one is not certain if the ghost one encounters is Spanish, English, Native American, Confederate, or Union!

One story that has circulated around the reenactment community for years (and has been told to us as happening to “a friend of a friend” by no less than two dozen people) involves an incident one night at the Pickett’s Mill battlefield, just west of Kennesaw Mountain near Marietta, Georgia. The details in the various retellings vary somewhat, but the gist is that two reenactors showed up after dark one night before the annual living-history exhibition on the battlefield (this is not unusual, for reenactors sometime travel hundreds of miles to events, not leaving until the workweek is done). Rather than go crashing through the thick, dark woods to the encampment site, they decided to sleep in their car in the visitor center parking lot, which is only feet from the Confederate lines during the battle. During the night they were awakened by the sound of masses of people moving around on the other side of the center, followed by “rebel yells” and (in some retellings of the story) the sounds of muskets discharging. Deciding that some of the other reenactors supposedly on the site were just out having a little moonlit fun, they stayed in their car and went back to sleep. The next morning upon rising and looking around for their compatriots, they discovered that the encampment area had been changed to one off-site and that no one except themselves had been on the battlefield all night.

Another story was related to us about an adjoining battlefield, New Hope Church, where an eminent artifact collector and historian from Atlanta was out with a companion walking the old battleground on the afternoon of May 27, 1964. A sudden spring thunderstorm blew in over the field, causing the two men to seek shelter in a nearby toolshed. Our source did not know what they encountered next, but the historian and his friend soon departed the field quickly, through the midst of the driving rain. Coming up to a nearby farmhouse, they sought shelter with the old farmer, who berated them for being out on the battlefield that day. “Don’t you know that nobody goes down in there on this day?” he asked. It was 100 years to the day after that terrible battle was fought, also during the midst of a driving thunderstorm.

These are the sort of stories that are delicious to read about, but the real rising-hair-on-the-neck feeling can only come from hearing them firsthand in the places they happened. Don’t hesitate to ask your guide or available rangers about what they may have seen, heard, or felt—it does give an exquisite flavor to the experience.

In all seriousness, there is something very different about the places we write about in this book. We have found the battlefields, ironically, to be some of the most peaceful places we’ve ever visited, as if all the energy has been sucked out of the area by the enormity of what happened there so long ago. As we have stood by the Peach Orchard at Shiloh, atop Snodgrass Hill at Chickamauga, on the ramparts of Fort McAllister near Savannah, on the porch at the Carter House in Franklin, in front of the row upon row of stark white tombstones at Andersonville, and in the open fields of Bentonville, there is an almost perceptible hush, as if the wind itself is reluctant to disturb the rest of those who are buried there. As we clambered through the overgrown trenches at Nickajack Ridge outside Atlanta and the thick woods near Griswoldville, we had the feeling that those who fell there have waited patiently for someone to tell of their sacrifice. These may not be ghosts in the proper sense, but the spirits of those who fought in those places are there all the same, and in some very real ways their bones are as well, given the “plant them where they fall” burial practices of the day. Tread lightly and allow them their well-deserved peaceful slumber.

At that point the Confederates had nearly split the Union forces in half and controlled their main line of communication to Chattanooga. Worse for Rosecrans, the momentum of their attack was carrying them straight toward his headquarters, across Brotherton Field at Widow Glenn’s cabin.

With the breach made, reinforcements would be all that was needed to completely break the Union lines and carry the day. Resistance in the retreating Union units was stiffening, and the breakthrough was bogging down after a few hundred yards’ advance. Benning requested not only infantry reinforcements but artillery as well, to counter the batteries directly in front that were shattering his ranks. Stewart’s division fared a little better, with Union batteries exhausting their loads of canister before his own attack drew too close.

Rosecrans sent word to his units to hold “at all costs,” and they responded well, putting up a solid wall of resistance even while their own ranks were blown apart. Several witnesses mentioned that whole companies simply ceased to exist in the rain of lead balls and iron shot. In typical Bragg fashion, however, no reserves were ordered in to exploit the situation. Without fresh men and ammunition, the breakthrough halted before any serious gain was made. As darkness fell, Hood’s brigades held their line, to be relieved later in the night, while Stewart’s men stayed put and hastily dug in just west of the LaFayette road.

Rosecrans and Bragg at the Battle of Chickamauga

Just after sunset, Major General Patrick R. Cleburne’s division (Lieutenant General Daniel H. Hill’s corps) was sent in from its reserve position up to the right of the rebel line and immediately swung into battle with its three brigades. Hitting Thomas’s units in the process of shifting positions, another fierce hand-to-hand combat ensued across nearly a mile-wide front, pushing the Union line back nearly three-quarters of a mile. Within an hour, however, it was too dark to see anything except the brilliant muzzle flashes seemingly coming from all directions, and both sides broke contact and pulled back after again suffering high casualties. The long day of fighting finally drew to a close without either side having gained any significant advantage.

The Union lines were now compacted into a 3-mile-wide continuous front, and all night long the men dug in and waited for the coming onslaught. Thomas’s men constructed a mile-long series of heavily reinforced, aboveground log emplacements, rather than entrenchments, during the night, along and just to the west of Alexander’s Bridge Road. Longstreet himself finally arrived at Bragg’s headquarters with the rest of his men about 11 p.m. Bragg divided his forces into two corps, giving Longstreet command of the left and Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk (an Episcopalian bishop in civilian life) command of the right.

All through the night both sides shifted their positions in preparation for the next day’s action. The Union right moved back away from the Viniard Field to the Glenn Field at Crawfish Springs Road, “refusing” the Confederate line, which stayed near the LaFayette road all night. On the north end of the line, Cleburne’s division was reorganized and reinforced by Breckinridge’s division to the right, extending the line to Reed’s Bridge Road and facing due west. Forrest’s cavalry had confirmed that the line outflanked the Union defenses and stayed to the right to guard their own flank.

Bragg gave orders that night for Polk’s corps to attack at daybreak in force on the extreme right, to be followed by attacks all down his line, and then followed in the same manner by Longstreet’s on the left. Both corps were to hit the Union line with every man they had, no reserves were to be kept back, and the attack was to be maintained until the Union line broke.

A reckless and unprincipled tyrant has invaded your soil. Abraham Lincoln, regardless of all moral, legal and constitutional restraints, has thrown his abolition hosts among you, who are murdering and imprisoning your citizens, confiscating and destroying your property, and committing other acts of violence and outrage too shocking and revolting to humanity to be enumerated.

—General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard

of the Confederacy, in a proclamation to the people of Virginia

Sunday morning dawned with a bloodred sun through the fog and battle haze, but no sounds of gunfire reached Bragg’s headquarters. Riding forward to reconnoiter the ground personally, the only sounds he heard were axes chopping and trees falling within the Union lines a few hundred yards away as they continued to strengthen their positions. Continuing on, he found the troops on the right flank drawing their rations and not even close to being ready for battle. No doubt throwing one of his famous temper tantrums, Bragg sent for Polk and his corps and divisional commanders.

Reading the naturally self-serving after-action reports of “who said what” and “when I received my orders,” it was nearly impossible to ascertain with any degree of accuracy exactly what had caused the delay. The divisional commanders all stated that they had received their final orders at 7:25 a.m., but Hill claimed this was the first he had heard of any attack order. It is known that there was some serious infighting among the Confederate high command, and that a rift over who was senior to whom had developed between Polk and Hill. Bragg himself was one of the most widely despised officers in the entire Confederate Army, hated and distrusted by officer and enlisted man alike, which only increased the communication problems. The only certainty was that no attack went off at dawn, and the Union line gained in strength by the hour.

At about 9:30 a.m. the attack finally got under way (this time and subsequent ones are also disputed in different reports). Breckinridge’s division led off with a three-brigade front. Moving forward about 700 yards, Brigadier General Benjamin H. Helm’s rebel brigade was the first to make contact, with the 2nd and 9th Kentucky and 41st Alabama Infantry Regiments storming the barricades held by Brigadier General John H. King’s 3rd Brigade (Brigadier General Absalom Baird’s 1st Division, Thomas’s XIV Corps). As each brigade advanced, the next in the line should have moved into position for support, but for some unknown reason, no brigade came up on Helm’s left to support him, allowing enfilade fire to hit him from the Union forces now to his left.

The assaulting regiments were nearly torn to pieces, and the Union lines held fast. Helm, Mary Todd Lincoln’s brother-in-law, was mortally wounded and died later that day. What was left of his brigade, along with brigadier generals Daniel W. Adams’s and Marcellus A. Stovall’s brigades, moved farther to the right and around the long line of fortifications, where they ran headlong into and captured a two-gun artillery battery and pushed back the extreme left of Baird’s division. Stovall’s brigade finally halted just to the Union left and rear at the LaFayette road (near the present-day visitor center), and Adams’s moved up to his right in the Kelly Field.

Acting against specific orders, Polk had sent in his units one at a time rather than as a united front and had held back Walker’s corps in reserve. To try to shore up this failed attack, Walker was sent in at about 11 a.m. with orders to attack the same set of fortifications. Once again each brigade was thrown into the battle as it came into line, rather than as divisional- or corps-size assaults, and once again the attack was halted and repulsed. Another brigade commander was killed during the action, Colonel Peyton H. Colquitt.

A little to the south and the left, at about 10 a.m., Cleburne’s division was ordered into the fight. Ordered to “dress” on Breckinridge, who was already heavily engaged, he instead moved too far to the left, and his units milled about getting organized for some time before committing to battle. Rather than pushing back Breckinridge’s command, his three divisions stormed the heavily defended ramparts held by Major General John M. Palmer’s 2nd Division (Major General Thomas L. Crittenden’s XXI Corps), but they were thrown back with very heavy losses.

This piecemeal advance of regiments and brigades continued on down to the left of Polk’s command, but while inflicting heavy casualties on the Union defenders, it proved unable to bring enough force at any one point to break the strong line of emplacements. Throughout the morning, Thomas shifted his units around to meet each newly developing threat, and so far Polk’s tactics had not been able to counter this.

At about 10 a.m. Captain Kellogg of Thomas’s staff was riding from his location to Rosecrans’s headquarters. As he passed by Brannon’s assigned position just north of the Brotherton farm, for some reason he failed to see the men in their entrenched position. Kellogg reported this to Rosecrans a few minutes later, who believed without confirmation that this meant that a hole existed in his lines and promptly issued orders for Brigadier General Thomas J. Wood to move his 1st Division from in front of the Brotherton cabin north to link up with Major General Joseph J. Reynold’s 4th Division and close this supposed gap.

Rosecrans had been having just as many infighting problems with his top commanders as Bragg, and Wood happened to have been personally and profanely berated by Rosecrans for failure to promptly obey orders only an hour previous. Wood knew full well that Brannon was exactly where he was supposed to be, and despite the warnings of his own staff officer that such a move would be disastrous, he decided to follow his orders to the letter. Wood’s division moved out at 11:15 a.m., opening up a nearly 1,500-foot-wide undefended gap in the lines in the process.

Brotherton cabin

Just on the other side of the LaFayette road at the Brotherton cabin, the spot Wood’s men had just left, stood 16,000 men of Longstreet’s corps drawn up in line of battle.

Longstreet’s men had moved up into position during the night, and it took several hours to get them fed and resupplied for the coming assault. It was not until just before 11 a.m. that he was able to advise Bragg that he was fully in position and ready to step off. Bragg then gave the go-ahead, and Longstreet moved forward into one of the luckiest accidents in military history.

Fully expecting to run headlong into the same strongly defended line of emplacements that had tied up Polk all morning, Longstreet had arrayed his main assault force into a powerful, compact formation. Surviving elements of three divisions had been rearranged into three divisions of eight brigades total, commanded as a corps by Hood. Directly adjacent to the south stood another division commanded by Major General Thomas C. Hindman, with three brigades arrayed two forward, one in reserve. Another division (Brigadier General William Preston’s) stood in reserve to Hindman’s left and rear.

No more than five minutes after Wood’s division moved out of its position, four brigades assaulted side by side in a 3,500-foot-wide front (from left to right, those of brigadier generals Arthur M. Manigault, Zach C. Deas, John S. Fulton [Johnson], and Evander McNair) across the LaFayette road, the right two brigades smashing immediately through the just-abandoned breastworks. Raising their rebel yells, the leading regiments brushed aside what little resistance was left in the Union trenches and plunged ahead, passing on either side of the Brotherton cabin and heading for the tree line several hundred yards ahead at the double-quick.

The left two front brigades (Hindman’s division) moved forward at the same time but ran into well-defended log breastworks after about 300 yards. Moving at the double-quick, Deas’s and Manigault’s brigades assaulted the works without faltering, driving Brigadier General William P. Carlin’s 2nd Brigade (Davis’s 1st Division, XX Corps) out of their trenches and back in wild disorder. For the Union, Major General Philip H. Sheridan’s 3rd Division had also been shifting north just behind Carlin’s position, but it was also driven off the field by the fury of Hindman’s attack.

Brannon’s men soon found themselves under attack from three sides and pulled back to the north. Wood’s division, turning to go back to its original position, was pushed back also from the brunt of McNair’s men advancing up the Dyer Road. One after another, Union regiments on line abandoned their positions under pressure from the massive Confederate attack until the right side of the line completely collapsed.

The rout of most units in this part of the field became complete. With his headquarters under threat of capture and a wild confusion of men and horses swirling around him running to the rear, Rosecrans himself joined the flight of roughly half his army (his headquarters was only about a half-mile directly behind the Brotherton cabin). Abandoning the field with him was his aid, Brigadier General, and later President, James A. Garfield. Rosecrans headed dejectedly back to Chattanooga, believing that Thomas’s men had been routed as well and the field already lost. Garfield accompanied his commander north to the outskirts of Chattanooga and then he turned back to try to help save the rest of his army.

Thomas realized that with Rosecrans abandoning the field, all hope for victory was gone and the best he could do was fight a rear-guard action to save as much of the army as possible. Leaving his men still successfully holding off Polk in the entrenchments along the LaFayette road, he moved his headquarters and what was left of units from the right flank back to Snodgrass Hill. With the broken and shattered remains of 19 regiments and 2 artillery batteries, he set up a line of defense around the top of Snodgrass Hill and the adjoining Horseshoe Ridge under the direct command of Wood and Brannon. All were terribly low on ammunition, and no resupply or reinforcement was thought possible.

Fast on Thomas’s heels, Longstreet knew if he could throw him off the small hill then he could cut up the Army of the Cumberland piecemeal as it fled back to Chattanooga. He sent Bragg an urgent request for all available reserves, so to finish the battle as quickly as possible. Bragg replied that there were no available reserves, as everyone on the field was now committed with either his corps or Polk’s, and Polk’s men were “too badly beaten” to be shifted to Longstreet.

About 1:30 p.m., Longstreet’s attack opened up again with Brigadier General Joseph B. Kershaw’s division (McLaw’s) attacking up the slope of Snodgrass Hill from the southeast. His force nearly gained the crest of the hill before being violently thrown back. Kershaw was followed in rapid succession by a continuous series of assaults all along Snodgrass Hill and Horseshoe Ridge, each one being beaten back with increasingly heavy casualties on both sides.

About 3:30 p.m., with Longstreet’s assaults nearly piercing his lines at several points and his line of men becoming dangerously low, Thomas turned to look to the north and his line of retreat, wondering if the time had come to leave. Just then he spotted a column of infantry heading his way. Knowing that there were no reserves that could be sent his way, he prepared what defense against them that he could hastily muster, when their colors finally caught the breeze. It was Major General Gordon Granger with two brigades of his reserve corps, coming up from their position at Rossville, Georgia. Granger had observed Longstreet’s men piling into Thomas, and in a great fury he violated his specific orders from Rosecrans and moved some of his reserves up to relieve Thomas’s beleaguered post.

Going immediately into action, they shared the ammunition they had brought with Wood’s and Brannon’s men and jumped into the line of entrenchments just in time to meet another Confederate assault. It, too, was beaten back, along with the next, and the next. As sunset approached, almost everyone along the Union line had completely run out of ammunition, and the Confederates were massing for another assault. Granger gave the order to fix bayonets.

Three more assaults were thrown back at the very crest of the hill in fierce hand-to-hand combat. At 5:15 p.m., in the midst of yet another Confederate attack, Thomas received word from his absent commander Rosecrans, now safely in Chattanooga, for him to take charge of remaining forces and move them in a “threatening” manner to Rossville. He immediately passed the word along to the other commanders and made preparations to pull out at sunset.

Just as the sun was setting and Thomas’s men started to pull out of their positions, another strong Confederate charge sent Longstreet’s men up over the crest of both Snodgrass Hill and Horseshoe Ridge, into the midst of the retreating regiments. Massive confusion erupted, with many whole Union companies and regiments being made prisoner and others managing to slip away without harm. Their men exhausted but with “their dander up,” Longstreet and Polk both begged permission to chase after the retreating Union Army, but Bragg refused.

Terribly shaken by his own severe casualties and typically fretting over what he should do next, Bragg instead did nothing. Thomas slipped away unmolested back to Rossville with the remnants of his command, and Rosecrans began organizing his shattered army within the strong fortifications of Chattanooga. Not until September 22 did Bragg finally move the Army of Tennessee up to Missionary Ridge overlooking Chattanooga, only to find it was far too late to finish what had started off so well.

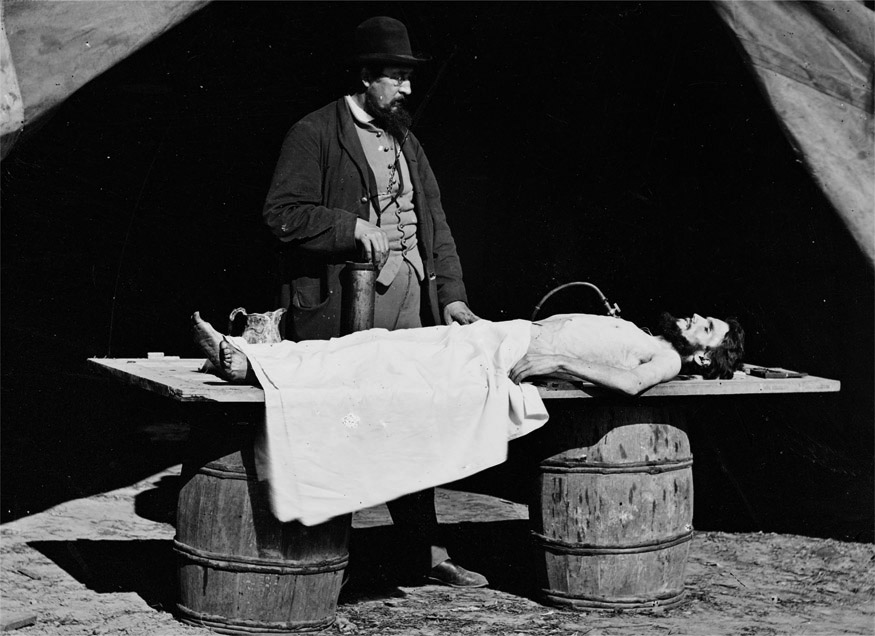

The Angel of Death was ever present during the two days of vicious fighting. Chickamauga was one of the bloodiest battles of the entire war, with more than 16,000 casualties among the 58,000 Union soldiers and 18,000 casualties among the 66,000 Confederate troops. Only the three days at Gettysburg produced a higher casualty figure. Dozens of officers on both sides were killed in the close fighting, including one Union and three Confederate generals.

Most of the dead were buried in unmarked trenches dotted around the battle areas, but one private lies today in the only marked grave on the battlefield. John Ingram, who had lived with his family in this area before the war, was a close friend of the Reed family, whose house stood nearby. Finding his body among his fellow slain of the 1st Georgia Infantry Battalion, they buried him near where he fell and maintained his grave for many years.

The Union Army was terribly affected by their defeat here, but in their despair they found a true hero. Thomas’s efforts were widely publicized by Northern newspapers desperate for some good news from Chickamauga; they dubbed him the “Rock of Chickamauga” for his stand at Snodgrass Hill. Rosecrans fared less well, relieved of his command soon after for his continued displays of sheer incompetence in favor of Thomas.

Embalming surgeon at work on soldier’s body

The Chickamauga and Chattanooga

National Military Park

Fort Oglethorpe, GA

(706) 866-9241

Today the Chickamauga portion of the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park is one of the best-preserved and -marked battlefields of the war. Operated by the National Park Service, this was the first and largest of four parks established between 1890 and 1899 by Congress (the others being Shiloh, Gettysburg, and Vicksburg), largely as a result of efforts by brigadier generals Henry Van Ness Boynton and Ferdinand Van Derveer, veterans of the Union Army of the Cumberland. This park was officially dedicated in a three-day ceremony starting on September 18, 1895, the 32nd anniversary of the battle. Nearly all the 1,400-plus signs and monuments on the 5,500-acre park were personally located by Boynton and other veterans of the battle.

At the time of the dedication, very little had changed in these fields since the great battle, so little restoration work was required outside of clearing undergrowth and new forests. The National Park Service has done a superb job in maintaining the area, with improvements added to accommodate increasing numbers of tourists and to better interpret the action, while not detracting from the original look and feel of the grounds.

Just inside the north main gate is a large and well-appointed visitor center that houses a small collection of paintings and general artifacts, an excellent bookstore, and very informative displays on the battle. A special feature is one wing devoted to the Fuller Collection of American Military Shoulder Arms, a donated 335-piece collection of infantry small arms centering on Civil War pieces. A 150-seat multimedia theater presents a dramatic 23-minute film about the battle at Chickamauga and the subsequent establishment of Chattanooga National Military Park. There is no admission charge for the film, and it is shown at the top of the hour year-round. Outside the newer portion of the restored and renovated 1935 building is a well-presented collection of the major types of artillery used during the battle.

The park is quite large, and it will take several visits to study the battle in real detail, but a well-marked, eight-stop, 7-mile auto tour will take you to most of the significant areas in two to three hours—depending, of course, on how often you pop out to read markers and view the monuments! A two-hour audiotape-guided tour is also available from the bookstore. Be sure to stop by the information desk and ask for a map of the tour.

For the serious student of military history, this place is absolute nirvana. There are about 700 cast-iron markers dotting the fields and woods, detailing exactly who fought at that point and what they did. Blue-lettered signs detail Union movements; the red-lettered ones detail Confederate movements. Small cast-iron signs mark houses that stood during the battle, small piles of cannonballs mark army and corps headquarters sites, and eight large pyramids of cannonballs mark the deaths of brigade commanders. In addition, more than 600 monuments and 250 cannon mark other significant sites. Quite a few sites throughout the battlefield feature modern maps, photos, and even audio descriptions of the events that transpired. Miles of hiking trails wind all through the woods; maps and guides are available from the information desk in the visitor center.

An interesting note is the number of monuments with acorns as part of their design. These indicate units and positions of Thomas’s XIV Corps, which “stood like an oak tree” atop Snodgrass Hill.

Be aware that a great deal of action occurred on either side of the LaFayette road, which is the old US 27 today. A modern “bypass” highway has reduced traffic levels inside the park. Please also be aware that the entire battlefield is for all practical purposes a graveyard. The standard practice throughout the Civil War was to bury the dead either where they fell or very close by, and here they were buried in shallow mass trenches that were never marked. No one knows where these graves are located, so please tread lightly.

Admission to the Chickamauga battlefield and Cravens House is free. There is a small entrance fee to Lookout Mountain Battlefield at the Point Park unit. The park is open between sunrise and sunset.

Hotels and motels are available in limited quantity in Fort Oglethorpe, in Chattanooga to the north, and scattered all along I-75. For a central spot to tour both the Chattanooga and Atlanta campaigns, we suggest you stay in or near Dalton, east off I-75 at exits 333 and 336. For more information on Dalton, visit www.daltoncvb.com.

There is one very interesting hostelry we can highly recommend here—a former headquarters and hospital now open as a bed-and-breakfast.

| Gordon-Lee Mansion B&B | $$–$$$ |

217 Cove Rd.

Chickamauga, GA

(706) 375-4728

(800) 487-4728

One of the very few period structures on the battlefield itself that survived the war is in the adjacent Chickamauga Village. Used as Rosecrans’s headquarters just before the battle, it became the center of seven large Union hospitals on its grounds during the battle. Some of the downstairs rooms were used for surgery, with wagons placed just under the windows for amputated limbs to be thrown onto. Originally built in 1847 by James Gordon, it is open now as a bed-and-breakfast.

Both US 27 and GA 2 immediately outside the north gate of the park have just about any type of fast food you may care for; for finer dining, travel US 27 to Chattanooga 20 miles north. Check at the Chattanooga Visitor Center at 2 Broad St. (follow the signs to the Tennessee Aquarium; it is directly adjacent; www.chattanoogafun.com) for suggestions and directions.

We strongly recommend that you follow your visit to Chickamauga with one to Chattanooga to see where these actions finally ended. See the chapter on Chattanooga for a full description of sites and directions.

Close by to the east is where the Atlanta Campaign of 1864 started, and we recommend a visit to Dalton, Rocky Face Ridge, and Resaca, all well within an hour’s drive. Please see the next chapter for details and directions.