Atlanta to Savannah: The March to the Sea

Map of Sherman’s March to the Sea

Sherman’s Georgia campaign, another name given for his famed March to the Sea, can be viewed as simply an extension of his Atlanta campaign, which began in the northwestern mountains in May 1864. His original goal—cutting the critical transportation and manufacturing center of Atlanta off from the rest of the Confederacy—having been met by early September 1864, Sherman pondered what to do next. One of his earliest thoughts was to strike southwest toward LaGrange and West Point while Union forces stationed in Mobile and Pensacola marched north to meet him, opening the Chattahoochee and Appalachicola Rivers to Union control.

Another considered, then rejected, plan was to strike toward the state capital at Milledgeville, and then turn on Macon, Augusta, and “sweep the whole State of Georgia,” but concern over the still-undefeated Confederate Army of Tennessee just outside Atlanta gave him serious pause. His primary concern was that his supply line snaked through a relatively narrow corridor from Atlanta more than 100 miles to the north in Chattanooga and from there another 130 miles north to the main Union base at Nashville. Both the Confederate Army of Tennessee under Major General John Bell Hood and Major General Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry corps up in Tennessee threatened to cut off this supply route at any given time.

Researching population and agricultural records for every county in Georgia, Sherman finally concluded that his 60,000-plus men could live off the land for a short time if they set off cross-country to join a Union army somewhere along the Atlantic Coast. Under great pressure to send his army south to rescue Union prisoners at the notorious Camp Sumter prisoner-of-war camp near Andersonville, Georgia, Sherman admitted that going down the Flint River to accomplish this would probably be the safest course of action. However, he had objectives other than simple, safe military maneuvers.

Sherman’s grand army had simply walked into the contested city of Atlanta after Hood had abandoned it during the night of September 1, 1864. Hood, in one of his many rash decisions, had sent his entire cavalry force north to strike at the Union supply lines in Tennessee, leaving him without scouts to report on what his Union opposite was up to. Sherman, learning of the poor tactical decision, took advantage of the situation by shifting part of his forces to the south of Atlanta, near Jonesboro, and cut the single remaining railroad supply line into the city. Hood, left without means of supply or reinforcement and faced with the prospect of a protracted siege, took what opportunity was left and snuck his remaining combat forces out of the city under cover of dark.

Rather than face the small but combat-hardened group of veterans from Hood’s army at their new defense lines near Lovejoy Station, Sherman elected to march his army into the city and take over the strong belt of fortifications himself. Hood, faced with the prospect of bleeding his army dry against the very fortifications they had built, decided instead to take his army north, cut the Union supply line, and try to starve Sherman out.

Sherman had some interesting problems to deal with in Atlanta in addition to the roaming Confederate Army at his gate. The extensive line of fortifications built by Confederate engineers and slaves around Atlanta was simply too large for even his huge army to fully man, so he ordered his own engineers to tighten it down to a smaller ring of artillery emplacements defended by trenches for infantry. The nearly 30,000 civilians still within the city troubled him, for he did not wish to “waste” any of the mountains of supplies flowing down from Chattanooga on the noncombatants.

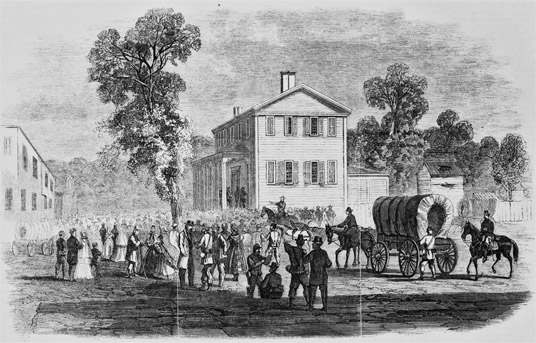

On September 8, Sherman gave one of his most controversial orders of the war: “The city of Atlanta, being exclusively required for wartime purposes, will at once be evacuated by all except the armies of the United States.” All civilians would be transported under flag of truce 10 miles south to Rough and Ready and then unceremoniously dumped in the unprepared area without provision for shelter or food.

Atlanta citizens wait to get passes from the provost’s office to leave the city on Sherman’s orders.

Needless to say, this act provoked a howl of protest from Confederate civilian and military authorities. Hood stated in a letter to Sherman, “Permit me to say that the unprecedented measure you propose transcends, in studied and ingenious cruelty, all acts ever brought to my attention in the dark history of war.” Mayor James M. Calhoun of Atlanta protested that the majority of citizens left (mostly women and children) could not stand up to the coming winter without shelter or food. In a letter to Sherman, he wrote that the act was “appalling and heartrending.”

Sherman was not impressed. In a lengthy reply to Hood’s letter, he reiterated his intentions and blasted Hood for suggesting it was anything truly unusual:

In the name of common sense, I ask you not to appeal to a just God in such a sacrilegious manner. You, who in the midst of peace and prosperity have plunged a nation into war, dark and cruel war, who dared and badgered us into battle, insulted our flag, seized our arsenals and forts that were left in the honorable custody of a peaceful ordnance sergeant, and seized and made prisoners of war the very garrisons sent to protect your people against negroes and Indians … Talk thus to the Marines, but not to me … if we must be enemies, let us be men, and fight it out as we propose to do, and not indulge in such hypocritical appeals to God and humanity.

Sherman had no intention of changing his orders, and on September 10 the first wagonloads of civilians left Atlanta. Hood was beside himself with the barbarity of Sherman’s actions and just couldn’t leave it be without a parting shot. “We will fight you to the death!” he wrote back to Sherman. “Better die a thousand deaths than submit to live under you….”

By October 1, Sherman finally made up his mind where to go next. Ordering Major General George H. Thomas back to Chattanooga with two corps to defend Tennessee, he stripped down his remaining army to a handpicked fighting force of 55,255 infantry, 4,588 cavalry, and 1,759 artillerymen, with 68 guns organized into four army corps. Writing a series of letters to his friend and commander, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, back in Washington, he outlined his planned offensive. “Until we can repopulate Georgia (with Unionists), it is useless for us to occupy it; but the utter destruction of its roads, houses, and people will cripple their military resources … can make this march and make Georgia howl.” He further advised that he was sending his wounded and unfit soldiers back up to Tennessee, “and with my effective army, move through Georgia, smashing things to the sea.”

Sherman’s only real worry was that the few good roads and frequent stream and river crossings in southern Georgia could allow the remains of Hood’s army and small bands of Georgia militia and home guards to delay his advance to an unhealthy degree. Unwittingly, Hood himself helped relieve some of this concern, with a renewed offensive against Sherman’s rear.

Realizing that there was no way his battered army could ever hope to take Atlanta back by force, Hood, with President Jefferson Davis’s blessings, marched his troops out of camp near Palmetto northward, hoping to cut Sherman’s supply lines north of Atlanta and force him to turn and fight him there. Crossing the Chattahoochee River near Campbellton on October 1, he continued north for two days, finally encamping near Hiram. Major General Alexander P. Stewart was ordered to move east to attack and cut the Western & Atlantic Railroad line at Big Shanty (now Kennesaw), Acworth, and Allatoona.

Like much in the war, this small but important battle had never been part of the Confederate war plan. Also like many other Confederate victories, it happened as the result of quick action, good luck, and stealth but, ultimately, led to disaster. After Stewart’s men surprised and captured about 170 Union troops at Big Shanty on October 4, he quickly moved north and grabbed a larger garrison at Acworth.

Excited over what he considered easy victories, Hood ordered Major General Samuel G. French to march his division up the tracks to Allatoona Pass, where they were to take and destroy the railroad bridge. French brought along three battalions commanded by brigadier generals Sears, Cockrell, and Young. Because the two prior rail stops had been lightly protected, Hood believed Allatoona would be a similar easy mark. Unknown to the Confederates, however, was the fact that Sherman had made the tiny settlement into a logistics base, heavily fortified it, and had ordered Brigadier General John M. Corse’s division forward to garrison it. On both sides of the deep rail cut, Union forces had built stout defensive reinforcements. On the west side of the cut was a defense called, for its shape, the Star Fort, which was surrounded by railroad ties.

Approaching Allatoona from north, west, and south, French sent a short message to his adversary Corse:

Sir: I have the forces under my command in such positions that you are now surrounded, and, to avoid a needless effusion of blood, I call upon you to surrender your forces at once, and unconditionally. Five minutes will be allowed for you to decide. Should you accede to this, you will be treated in the most honorable manner as prisoners of war.

Corse was not cowed: “Your communication demanding surrender of my command, I acknowledge receipt of, and respectfully reply, that we are prepared for the ‘needless effusion of blood’ whenever it is agreeable with you.”

From the west, French sent in Brigadier General Francis M. Cockrell’s Missouri Brigade and Brigadier General William H. Young’s (Ector’s) Brigade. Pushing through one defensive line after another, fighting hand to hand with clubbed rifles and bayonets, fighting advanced to within a few feet of the Star Fort. Fighting rapidly intensified, with the Confederate advance being stopped before it overran the fort. Soon came warnings that a Union force had been spotted moving rapidly toward the pass. French pulled back his troops and marched his to rejoin Hood in the west.

Throughout the all-day fight, a Union signal post at Kennesaw Mountain repeated to Corse: “General Sherman says hold fast; we are coming.” Popularizing the expression, “hold the fort,” the message was meant mainly for morale; no additional infantry arrived until two days later. It seems that forces spotted by the Confederate scouts were simply Union cavalry on a scouting mission.

Though barely remembered this century and a half later, casualties were exceptionally high, even for the Civil War. Corse reported 706 dead and wounded; French also reported 706 casualties (including 70 officers), about 30 percent of each side’s total force. Young was wounded and captured shortly afterward. In his report to Sherman, the battle-hardened Corse reported that he, too, had been wounded: “I am short a cheek bone and an ear but am able to lick all hell yet!” Later, when Sherman came up to inspect the aftermath, he was apparently unimpressed with Corse’s wounds: “Corse, they came damn near missing you, didn’t they?”

This morning the enemy attacked our pickets. They planted their artilry so they had good range of us. They drove us out of our rifel pits about 11 a.m. and we fell back in the fort and then we held them and fought them until nearly 4 p.m. The timber is laying full of dead and some wounded. The wounded in our company Henry Hockman in left leg, J Garman fnger shot off, E Kahley shot in back, J Humpfrey in the side, [unidentified words], H C Carl through the breast, J Stewart slight in leg, Danil Dauber slightly in arm. Killed Simon [last name unidentified].

—Private Thomas Jefferson Moses, 93rd Regiment, Illinois Volunteers, Union Army, description of battle of Allatoona Pass, October 5, 1864 (all spelling original, from his diary entry)

Following the decisive loss at Allatoona Pass, Hood elected to continue north, hitting the Union garrisons at Rome, Resaca, Dalton, and Tunnel Hill before turning west into Alabama. Sherman initially sent a force of some 40,000 men chasing after him but soon wearied of the endless pursuit. Hood’s strategy here is uncertain, but if it was to keep Sherman bottled up in northern Georgia, it both succeeded and failed. When Hood slipped away after the Union troops deployed for battle at LaFayette (just south of the Chickamauga battlefield) on October 17, Sherman remarked that Hood’s tactics were “inexplicable by any common-sense theory … I could not guess his movements as I could those of Johnston.” After a total of three weeks of chasing the fast-moving Army of Tennessee, Sherman ordered his forces to return to Atlanta and prepare for a march to the south.

Warned by Grant that Hood was taking his army north into Tennessee to threaten his supply lines, Sherman remarked, “No single force can catch Hood, and I am convinced that the best results will follow from our defeating Jeff Davis’s cherished plan of making me leave Georgia by maneuvering.”

At the same time, Davis was begging Hood “not to abandon Georgia to Sherman but defeat him in detail before marching into Tennessee.” Hood replied that it was his intent to “draw out Sherman where he can be dealt with north of Atlanta.” In his postwar memoirs, Hood clung to this unrealistic stance and his hopes of defeating both Sherman and Thomas’s powerful force in Tennessee:

I conceived the plan of marching into Tennessee … to move upon Thomas and Schofield and capture their army before it could reach Nashville and afterward march northeast, past the Cumberland River in that position I could threaten Cincinnati from Kentucky and Tennessee … if blessed with a victory (over Sherman coming north after him), to send reinforcements to Lee, in Virginia, or to march through gaps in the Cumberland Mountains and attack Grant in the rear.

It was whispered by not a few members of the Army of Tennessee that Hood was half-mad from his injuries, shot in the arm at Gettysburg and having a leg shot off at Chickamauga shortly thereafter. Widely viewed as a gallant fighter, his leadership did not impress those under him in the sense that his tactics killed a lot of his men. Private Sam Watkins said, “As a soldier, he was brave, good, noble and gallant, and fought with the ferociousness of the wounded tiger, and with the everlasting grit of the bull-dog; but as a general he was a failure in every particular.”

Hood continued his march north, and Sherman, upon hearing the news, couldn’t have been happier. “If he will go to the Ohio River, I will give him rations.” Just before Hood’s eastward-ranging cavalry cut the telegraph lines, Sherman sent one last message to Grant:

If I start before I hear from you, or before further developments turn my course, you may take it for granted that I have moved by way of Griffin to Barnesville; that I break up the road between Columbus and Macon good and if I feign on Columbus, I will move by way of Macon and Millen on Savannah; or if I feign on Macon, you may take it for granted I have shot toward Opelika, Montgomery and Mobile Bay. I will not attempt to send couriers back, but trust to the Richmond papers to keep you well advised. I will see that the road is completely broken between the Etowah and the Chattahoochee, and that Atlanta itself is utterly destroyed.

Content with his plans, happy about Hood being more than 100 miles to his rear, and with his army primed and ready for action, Sherman had but one task left before turning his attention on gaining the sea before winter set in.

Planning to begin his march out of Atlanta southward on November 16, Sherman issued orders that anything of military value in the city be destroyed before they departed. Giving the task over to his chief of engineers, Captain Orlando M. Poe, Sherman intended to render useless anything even remotely related to manufacturing, transportation, or communications. Poe took this order and applied it quite liberally, without any objection from Sherman. Starting on the afternoon of November 11, block after block was set afire, the contents being pillaged and looted beforehand by large gangs of drunken Union soldiers and sober Southern citizens alike.

North of Atlanta, Sherman gave orders that anything of “military value” be destroyed by his troops gathering for the march south. Rome, Acworth, and Marietta were all consigned to the torch, and soon little was visible of the once-pretty small towns but heaps of smoldering ruins and lonely chimneys standing like pickets.

An authentic [hardtack] cracker could not be soaked soft, but after a time took on the elasticity of gutta-percha.

—John D. Billings, in his book, Hardtack and Coffee

To conduct his destruction more efficiently, Poe had devised a new machine consisting of a 21-foot-long iron bar swinging on chains from a 10-foot-high wooden scaffold. With a gang of soldiers to move and swing it, it was a devilishly clever way to knock down whatever struck his fancy. The railroad roundhouse, factories, warehouses, residences, and masonry buildings of all description were soon reduced to piles of rubble. Under other buildings Union soldiers piled stacks of mattresses, oil-soaked wagon parts, broken fence rails, and just about anything else that would burn. Atop everything they piled artillery shot and shells abandoned by Hood’s retreating army. In a touch of irony, sentries were then posted to prevent “unauthorized” acts of arson.

Finally ready to move out of Atlanta, Sherman ordered Poe to start the fires late on the afternoon of November 15. Within a few minutes the “authorized” fires had been set, at first confined to factories and warehouses containing Hood’s abandoned supplies. An early evening wind soon built up the fires, and spraying sparks and burning cinders in every direction, the fires spread like, well, wildfire. Pleased by the sight of the soon out-of-control fires raging through the city, Sherman was moved to remark only that he supposed the flames could be visible from Griffin, about 45 miles to the south.

As a sort of explanation to his staff, who were starting to view the wanton destruction with unease, Sherman remarked,

This city has done more and contributed more to carry on and sustain the war than any other, save perhaps Richmond. We have been fighting Atlanta all the time, in the past; have been capturing guns, wagons, etc. etc., marked Atlanta and made here, all the time; and now since they have been doing so much to destroy us and our Government, we have to destroy them, at least enough to prevent any more of that.

As the huge fire built and built, block after block literally exploded into flame, the thick smoke choking the Union soldiers who clapped and danced with glee among the ruins, barely waiting until the flames died down to start their looting and drunken revelry once again. What initially escaped the “authorized” fires did not escape these undisciplined wretches, who helped spread the flames by burning homes and businesses to cover up their crimes. In the midst of the chaotic riot, the 33rd Massachusetts Regimental Band stood, calmly and righteously playing “John Brown’s Soul Goes Marching On.” Major George Ward Nichols, Sherman’s aide-de-camp, remarked without a hint of sarcasm that he had “never heard that noble anthem when it was so grand, so solemn, so inspiring.”

Other Union soldiers and officers viewed the destruction differently, remarking that the burning and looting of private property was not necessary and a “disgraceful piece of business.” Another summed up the view more widely held by their Confederate opponents: “We hardly deserve success.”

As the flames died down overnight, dawn on November 16 revealed that more than 4,100 of the 4,500 buildings in town, including every single business, had been leveled by the flames and rioting Union troops. Sherman mounted his horse, Sam, and slowly led his men out of the ruined city, bound for Savannah and the Atlantic Ocean.

With the “business” in Atlanta taken care of, his men up and ready, and prospects of an easy adventure before them, Sherman ordered the march out of the city to begin. The 60,598 Union soldiers were deployed in two huge columns, sometimes called “wings.” On the morning of November 15, Brigadier General Alpheus Williams’s XX Corps headed off due east through Decatur toward Augusta. General Peter Osterhaus’s XV Corps and General Frank Blair’s XVII Corps formed the right column under overall command of Major General Oliver O. Howard and moved southward toward Macon. Early on the morning of November 16, Major General Jefferson C. Davis’s XIV Corps moved out behind Williams’s corps. The two-pronged attack was designed to fool Confederate defenders into thinking that Augusta and Macon were the targets of the separate wings, forcing them to divide their already inadequate forces while the two columns swung south and east and converged on Milledgeville, which was then the capital of Georgia.

To oppose the Union juggernaut was a pitiful handful of mostly irregular troops: Major General Gustavus W. Smith’s (combined) Georgia Militia, the battered remnants of the Georgia State Line—freshly arrived after leaving the march north with Hood’s army; a few home guard and hastily organized local militia groups; and the remnants of Major General Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry corps. All told, fewer than 8,000 men were available to try to stop Sherman, most of whom had never fired a rifle in combat before.

About 7 a.m. on the morning of November 16, Sherman rode his horse slowly out of the bombarded, burned-out hulk of a once-thriving city along with the vanguard of his XIV Corps, down the dirt road leading toward Decatur and Stone Mountain. Stopping briefly, he turned to take another look at the scene of his greatest triumph and some of his greatest sorrows. From his vantage point he could barely make out the copse of trees where his beloved friend, Major General James Birdseye McPherson, had been shot and killed on July 22. Setting his battered hat back on his head and unwrapping another cigar to chew on along the way, he set his horse to a walk and left the city without uttering a word to anyone. In his memoirs, he remarked,

Then we turned our horses’ heads to the east; Atlanta was soon lost behind the screen of trees, and became a thing of the past. Around it clings many a thought of desperate battle of hope and fear, that now seem like the memory of a dream … There was a “devil-may-care” feeling pervading officers and men, that made me feel the full load of responsibility, for success would be expected as a matter of course, whereas, should we fail, this march would be adjudged the wild adventure of a crazy fool.

Both columns moved out of Atlanta, one proceeding initially almost due east and the other south, with almost no opposition. Following Sherman’s orders to the letter and spirit, nearly everything of any value that they encountered was confiscated or burned, and assigned work gangs destroyed most of the railroad tracks. The rails were lifted and the cross-ties pulled out from under them and piled high and set afire; then the rails were held over the burning ties until they glowed red hot and twisted and bent into unusable pretzel shapes called “Sherman’s bow-ties.”

The only Confederate opposition to the first part of the march was a series of small to moderate-size skirmishes between Rough and Ready (10 miles north of Jonesboro; now called Mountain View) and East Macon, with elements of Wheeler’s cavalry.

The skirmishers and foraging parties created a nearly 60-mile-wide path of destruction as they went across Georgia. Slocum’s left wing moved like a blue buzz saw through Stone Mountain, Lithonia, Conyers, Social Circle, and Madison before encountering any resistance to speak of. At Buckhead (a small town, not the Atlanta suburb), Confederate sharpshooters caused a handful of casualties before being driven off; Sherman ordered the town totally burned to the ground in reprisal.

Howard’s right wing had moved in a southeasterly direction, hoping to give the impression that Macon was their destination. Moving through McDonough and Locust Grove, Howard ordered a turn more to the east at Indian Springs, to close in tighter with the left wing and head more directly to Milledgeville. By November 20, the closest flanks of both wings were within 10 miles of each other and just a day’s march from the Georgia capital.

From the start of the march, Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick’s 3rd Cavalry Division had ridden to the far right of Howard’s massed columns. He had been ordered to travel south—as close to Macon as he dared—and to tear up the railroad tracks as he went. He was then to close up again near Milledgeville. On November 20, he had a brief skirmish with Wheeler’s cavalry just east of Macon, quickly driving the Confederates back into the line of entrenchments surrounding the city.

The next day, a single regiment, Captain Frederick S. Ladd’s 9th Michigan, was sent to assault the small industrial town of Griswoldville, 10 miles east of Macon. Moving in without resistance, the cavalrymen soon destroyed most of the buildings in town, including the railroad station, a pistol factory, and a candle and soap factory. As they mopped up, Colonel Eli H. Murray’s 1st Brigade settled in for the night about 2 miles to the east.

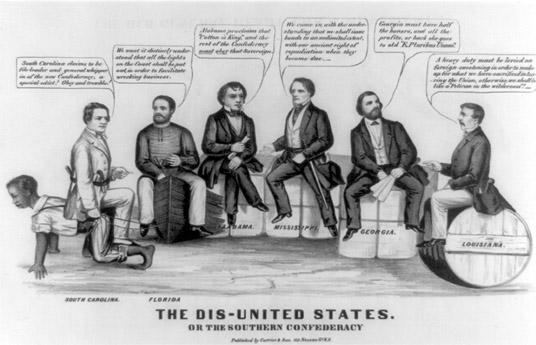

As the right wing set up just to their south, Slocum’s left wing made ready to enter Milledgeville, the Georgia capital. By November 19, it became obvious that the capital was Sherman’s real target, and pandemonium erupted. The Georgia legislature was then in session, and upon hearing of the danger promptly sprang into action. A law was quickly passed requiring every physically able male citizen to join in the armed resistance to the Union invasion, exempting only themselves and sitting judges from the noble sacrifice. Turning to issues of a more immediate nature, they then authorized expenditure of $3,000 in public funds to hire a train to carry themselves, their families, their furniture, and their baggage to safety.

Governor Joseph Emerson Brown, second from right, in a political cartoon of the period

Georgia’s governor, Joseph Emerson Brown, acted in an equally heroic manner. Stripping the governor’s mansion of everything that wasn’t nailed down (and a few things that were), he fled Milledgeville at a high rate of speed. Not far behind was the trainload of politicians from the legislature, who left with scarcely more dignity, actually pausing long enough to announce they were heading “for the front” before setting off in the opposite direction.

Civilians were equally panicked, but most lacked access to tax money to use to flee the city. A. C. Cooper, a local resident who had left Atlanta on Sherman’s approach in July, later wrote about the effect of Sherman on the horizon:

Reports varied; one would be that the enemy would be upon us ere long, as a few bluecoats had been seen in the distance, and we women were advised to pack up and flee, but there was blank silence when we asked, “Where shall we flee?” … Hurry, scurry, run here, run there, run everywhere. Women cried and prayed, babies yelled … dogs howled and yelped, mules brayed.

Late in the night of November 21, the first Union cavalry scouts entered the city, followed the next afternoon by the vanguard of the Union left wing, both without encountering the slightest act of resistance. Moving down Greene Street, officers of the XX Corps ordered the men into parade march, and with the bands playing selections of Northern patriotic tunes, made their way to the steps of the capitol building. With the bands sarcastically playing “Dixie,” a large U.S. flag was raised on the building’s tall flagpole.

As their men fanned out to see what they could steal in the city, officers amused themselves by occupying the recently deserted seats in the state legislature. In a high-spirited debate, the issue of secession was once again bandied about and promptly voted down. Sherman, who rode into town the next day, said that he “enjoyed the joke.”

As Sherman’s officers were amusing themselves playing politician in the legislative chambers, things were a bit more subdued just to the south. At dawn on November 22, Wheeler’s cavalry suddenly struck Murray’s encampment. A short but furious fight ensued, ending when reinforcements from Colonel Charles C. Walcutt’s 2nd Brigade (Union) rushed to Murray’s aid. Together they pushed the Confederate cavalrymen back through the burned-out town of Griswoldville before breaking contact and returning to their original positions, where they heavily entrenched atop a small, wooded ridge.

The previous day Lieutenant General William J. Hardee, commander of the Confederate forces facing Sherman, had become aware that the Union forces were bypassing his location at Macon and made the assumption that they were heading toward the critical supply and manufacturing depot at Augusta. A hastily assembled force was pieced together around Major General Gustavus Woodson Smith’s four regiments of the Georgia Militia and ordered to move out posthaste to protect the river city.

Besides the four brigades of Georgia Militia, the small task force contained Major Ferdinand W. C. Cook’s Athens and Augusta Local Defense Battalions; Captain Ruel W. Anderson’s four-gun Light Artillery Battery; and the decimated ranks of the combined two regiments of the Georgia State Line under Lieutenant Colonel Beverly D. Evans. With the exception of the State Line, which had been in nearly continuous combat since May 29, the overwhelming majority of the command were the archetypal “old men and boys,” this force representing the bottom of the barrel for reinforcements.

By Hardee’s direction, Colonel James N. Willis’s 1st Brigade, Georgia Militia, left early on the morning of November 22 along with Cook’s command, bound for Augusta via the road to Griswoldville, to be followed later that same day by the remaining commands. Hardee left at the same time for Savannah to help prepare its defenses, and Smith elected to remain in Macon to do administrative chores, leaving command of the task force to the senior officer present, Brigadier General Pleasant J. Philips. As the Confederates left Macon, quite a few in the ranks remarked about how much Philips had been seen drinking that morning.

As Philips’s command moved out, Howard’s entire right wing was also on the move, swinging a little more to the south and heading straight toward Griswoldville.

Philips left Macon with the main part of his command and marched steadily on, arriving at the outskirts of Griswoldville just after noon. There he found Cook’s defense battalions drawn up into a defensive perimeter, having spotted the well-entrenched Union lines just up the road.

Despite his explicit orders from both Hardee and Smith not to do so, Philips ordered preparations for an attack. Arranging his men perpendicular to the railroad tracks on the east side of town, Brigadier General Charles D. Anderson’s 3rd Brigade, Georgia Militia, was placed on the left, just north of the tracks. Brigadier General Henry K. McKay’s 4th Brigade was placed on Anderson’s right, just south of the tracks, and Philips’s own 2nd Brigade (now commanded by Colonel James N. Mann) moved in reserve to the rear of McKay. Evans’s State Line troopers moved forward in the very center as skirmishers, and Cook’s small battalions took the extreme right of the line. Anderson’s battery set up just north of the tracks near the center of the line.

Facing Philips’s small command was Walcutt’s strong 2nd Brigade, 1st Division, XV Corps, consisting of no fewer than seven reduced-strength infantry regiments (the 12th, 97th, and 100th Indiana; 40th and 103rd Illinois; 6th Iowa; and 46th Ohio), two cavalry regiments (5th Kentucky and 9th Pennsylvania), and Captain Albert Arndt’s Battery B, 1st Michigan Artillery. In all, about 4,000 mostly ill-trained and poorly equipped Georgia troops faced about 3,000 well-armed, well-entrenched, and combat-hardened veteran Union troops.

About 2:30 p.m. Philips ordered an all-out assault, and the ragged force began moving smartly across the open field toward the Union entrenchments. Major Asias Willison of the 103rd Illinois wrote in his after-action report what happened next:

As soon as they came within range of our muskets, a most terrific fire was poured into their ranks, doing fearful execution … still they moved forward, and came within 45 yards of our works. Here they attempted to reform their line, but so destructive was the fire that they were compelled to retire.

While most of Philips’s militiamen were being blown apart behind them, the State Line charged up the slope toward the Union position, only to be thrown back to the wooded base. The State Line charged several more times, meeting the same result, until Evans was seriously wounded and all retired from the field.

Most of the militiamen never got closer than 50 yards to the Union position but bravely held their ground and returned fire until dusk. Philips then ordered a retreat off the field, and the shattered ranks limped slowly back into Macon. Left behind were 51 killed, 422 wounded, and 9 missing. The Union lines were never in any real danger of being breached, but losses amounted to 13 killed, 79 wounded, and 2 missing in the brief fight. Walcutt himself was among the wounded and had to be carried off the field during the engagement, to be replaced by Colonel Robert F. Catterson.

With the pitiful remnants of Philips’s command safely back inside Macon’s defense by 2 a.m. on November 23, there was literally nothing standing between Sherman and any path he might choose to take next. That morning he issued new orders for all four corps to march east, the southern wing to head straight down the Georgia Central Railroad tracks toward Millen (near Buckhead Creek), while the northern wing and attached cavalry were to follow roads on the north side of the tracks. Their target was Camp Lawton, sometimes called Magnolia Springs, to rescue the estimated 11,000 Union prisoners recently brought there from Andersonville.

Early on the morning of November 24 the grand march resumed. Strangely, Milledgeville was left relatively intact, although all the government buildings, libraries, and some churches were ransacked and desecrated, and, once again, anything of value went along with the blue-suits.

Confederate resistance to this part of the march was nearly nonexistent, and those who did show up were grossly outnumbered. A good example is the defense of the Oconee River bridge near Oconee, where a force of exactly 186 men, the remnants of three separate commands, stood ready to keep Sherman from crossing. Even with nearly 1,000 cavalrymen from Wheeler’s command backing them up, more than 30,000 Union soldiers moved like a blue tidal wave down the road to crush them. Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed, and the tiny command was withdrawn before it made contact.

Sherman still today has a reputation as a thief and firebug in certain parts of Georgia, and this section of the grand march is where it was earned. All along, “authorized” foraging parties had scoured the countryside, collecting food for both soldiers and animals, and “jes’ a lil’ ” booty for themselves while they were at it. With military opposition nearly nonexistent, and no doubt with the blessings of many veteran officers, roving gangs of “bummers” roamed the countryside, casually stealing or destroying whatever caught their fancy. A 40-mile-wide path between Milledgeville and Millen was stripped down nearly to the roots; one traveler who crossed this area shortly after Sherman’s passing remarked that everything down to and including fence posts had either been taken or burned.

The destruction the Union troops were creating started to disturb many Union officers, although Sherman himself wasn’t among them. His attitude was that the Georgians had “forced” him to sponsor such actions by virtue of their secession and that he only regretted that he “had” to do such acts. The situation deteriorated so much at one point that even Sherman’s blindly admiring aide, Major Henry Hitchcock, noted in his memoirs that “I am bound to say I think Sherman lacking in enforcing discipline.”

Major General Blair’s XVII Corps arrived in Millen completely without resistance on December 1. Brigadier General Judson Kilpatrick’s 3rd Cavalry Division, moving rapidly to the north on Sherman’s personal order, arrived at the site of Camp Lawton on November 27, after a fierce resistance by Wheeler’s cavalry, only to discover that the Union prisoners had been moved again, this time to a rude camp near Blackshear, 10 miles northeast of Waycross and the Okefenokee Swamp in deep southeastern Georgia.

Sherman entered Millen on December 3 with the rest of his army. Deeply angered that he had been unable to rescue the POWs, he issued orders to march directly on Savannah beginning the next morning, and took out his wrath on the small town as they left. In a classic understatement, he mentioned in his memoirs, “I caused the fine depot of Millen to be destroyed, and other damage done … ”

Leaving Millen on the morning of December 4, all four corps marched directly toward Savannah and arrived nearly unmolested on the outskirts of the city between December 10 and 12. Along the way, two separate Confederate defenses were mounted with what remained of the Georgia Militia and the Georgia State Line supplemented by Wheeler’s cavalry and some local defense forces. On both occasions their commanders elected to withdraw in the face of such overwhelming Union opposition.

Map showing the investment and siege of Savannah, December 1864

Savannah’s defenses were formidable, stretching more than 13 miles from the Savannah River to the Little Ogeechee River and manned by just under 10,000 men—the bare remnants of every militia and state defense force that could be scraped together. In addition, more than 50 artillery pieces with a fair supply of ammunition sat in the ring of strong earthwork fortifications.

Sherman had a serious problem by this time; his supplies of food and clothing were running critically low, and there was nothing much in the surrounding salt marshes and swamps that he could send foraging parties out for. He desperately needed to make contact with the Union Navy, lying just off the coast, but the two possible river approaches were both guarded by powerful Confederate fortifications. Needing the supply line open and open fast, he personally ordered Brigadier General William Babcock Hazen to take his 2nd Division (XV Corps) down to the Ogeechee River 14 miles below Savannah, assault and take the Confederate fort there, and open the river to the Union Navy.

Fort McAllister, on Genesis Point guarding the entrance to the Ogeechee River, had been designed by Major John McCrady, chief engineer for the state of Georgia, in the late spring of 1861. Ordinarily, a massive masonry fort like Fort Pulaski or Jackson east of Savannah would be desirable, but these were time-, money-, and manpower-intensive projects, and McCrady had none of those resources.

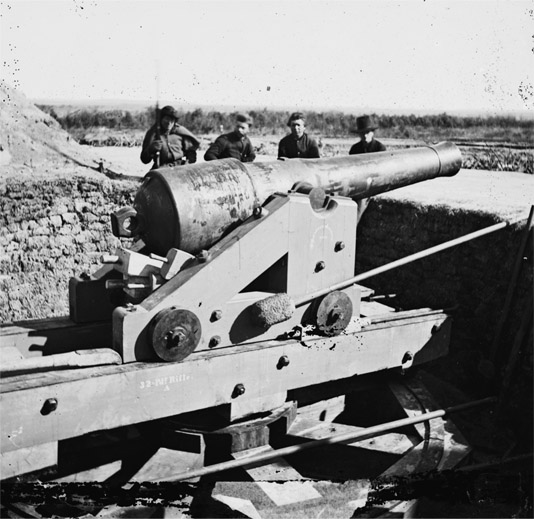

Instead he settled on a star-shaped, four-gun emplacement earthwork fort with walls 20 feet tall and 17 feet thick, originally intended to be equipped with four 32-pounder smoothbore cannons. The walls originally only faced the river, and a large earthen bombproof stood behind the gun emplacements to serve as a hospital. On June 7, 1861, the DeKalb Rifles, Company A, 1st Georgia Infantry Regiment under Lieutenant Alfred L. Hartridge was sent in to build and man the structure.

Fort McAllister on the Ogeechee River, photographed in 1864

Having an infantry company build and man an artillery post strikes one as an odd move, but the relatively few trained cannoneers were needed at posts where actual combat was expected. At backwater posts like Fort McAllister, infantry companies were customarily sent in to while away the war years.

Hartridge’s men did a very good job, clearing away the thick forest for a mile behind the fort site to provide clear lanes of fire and almost immediately setting about building up and improving the design.

By the time of Sherman’s arrival, the earthwork fort had been tripled in size and assaulted without success some seven separate times by Union gunboats. The DeKalb Rifles had long since departed for hotter action to the north, and a new commander had taken over, Major George W. Anderson. The garrison now consisted of about 230 men of the Emmet Rifles and the Georgia Reserves, along with real artillerymen of Captain Nicholas B. Clinch’s Georgia Light Artillery Battery.

The post by this time looked quite different, having been expanded into a five-sided fort 650 feet long and 750 feet wide, with a dry ditch studded with sharpened stake abatis surrounding it. More and heavier artillery had been brought in; two 32-pounder rifled guns, three 10-inch Columbiads, and three 8-inch Columbiads guarded the river approaches. To guard against expected infantry attacks, a rear wall slightly smaller than the front wall had been built and 12 field artillery pieces mounted atop it. To complete the armament, a 10-inch Tredegar Seacoast Mortar was mounted just outside the main defense walls.

The reluctant decision to make the post an earthwork arrangement proved most fortuitous. Fort Pulaski, a few miles to the north and long regarded as an impregnable guardian of the northern approaches to Savannah, had been breached by heavy rifled cannon fire on April 11, 1862, and surrendered after a mere 30 hours of shelling. The earth walls of Fort McAllister were nearly impervious to incoming fire, the walls either deflecting or swallowing up the Union artillery fire. Even if a shell buried deep in the earth before exploding, repairing the crater was a simple matter of shoveling a few wheelbarrow loads of dirt back in it. The thousand-year era of the heavy masonry fort had come to an end.

Sherman’s choice of the West Point graduate’s division to assault the Confederate fort was not a random one; not only had Hazen proven to be a capable and brave battlefield commander, but the 2nd Division was the same that Sherman had commanded at Vicksburg and Shiloh, one in which he “felt a special pride and confidence.” Hazen was ordered to take the fort as soon as possible, and he left the morning of December 13, marching rapidly down the old Hardwicke Road (now GA 144).

Shortly after noon, Hazen reached the causeway leading out to the fort and promptly captured the lone Confederate sentry posted there, Private Thomas Mills. After his capture, Mills revealed that his unit had placed “torpedoes,” or buried shells that exploded when stepped on, all along the soft sand causeway. Hazen ordered his men to immediately search for and dig up the land mines, delaying his approach to the fort.

By the time the road was made safe and the rest of his command came into line, it was after 4:30 p.m. Leaving nine regiments behind as reserves, Hazen moved the other nine regiments forward until they were arrayed in a semicircle around the isolated post, but no closer than 600 yards out. Confederate guns opened up, but with little effect. Union skirmishers ran forward, closing to within 200 yards of the fort, and began a damaging fire on the gunners. One of the fort’s major weaknesses was the fact that all the guns were mounted en barbette, or up on top of the ramparts, leaving the gunners exposed to rifle fire.

One of the “big guns” on the ramparts of Fort McAllister

Sherman, watching the action from atop a rice mill across the river, was nearly beside himself with impatience. As the afternoon wore on and dusk approached, he had a signal sent over to Hazen: “You must carry the fort by assault tonight, if possible.” A few minutes later a reply came back: “I am ready and will assault at once!” At 4:45 p.m. Hazen ordered a general assault to begin.

As the Union infantry sprang to their feet and began moving toward the fort at the double-quick, a furious rain of fire came from both sides. Moving up close to the ramparts, the Union men had almost entered the outer defense bands when huge explosions rocked the earth; more torpedoes had been buried all around the fort in the soft sand, making them nearly impossible to spot. Forcing their way forward despite the deadly mines and deafening cannon fire to their front, the 47th Ohio quickly gained the west wall and began running down it, looking for an opening to enter the fort. At the far northwestern corner, they discovered that the line of abatis stopped above the high-tide mark (it was then low tide), and they quickly ran through the opening and up onto the ramparts.

Almost at the same moment, the 70th Ohio and 111th Illinois Regiments pushed through the tangle of fixed defenses and appeared atop the ramparts nearby, and the fight quickly escalated into a vicious hand-to-hand brawl. The Confederate garrison refused to surrender, even in the face of such overwhelming odds. As each artillery position was overrun, the cannoneers continued to resist with ramrods swung as clubs and even just their fists, until bayoneted or beaten to the ground by the swarming blue masses. Each bombproof emplacement had to be taken individually, and the fight ended only when every last Confederate was killed, wounded, or beaten into submission. Hazen stated in his after-action report that “the line moved on without checking, over, under and through abatis, ditches, palisading and parapet, fighting the garrison through the fort to their bomb-proofs, from which they still fought and only succumbed as each man was individually overpowered.”

Although the whole action took only 15 minutes to complete, the fight was somewhat more than the Union soldiers had expected. The resistance of Captain Nicholas B. Clinch, commanding Clinch’s Light Battery, which was stationed on the landward side of the fort, was typical:

When [Clinch was] summoned to surrender by a Federal captain [Captain Stephen F. Grimes of the 48th Illinois], [he] responded by dealing a severe blow to the head with his sabre. (Captain Clinch had previously received two gunshot wounds in the arm.) Immediately a hand-to-hand fight ensued. Federal privates came to the assistance of their fellow officer, but the fearless Clinch continued the unequal contest until he fell bleeding from eleven wounds (three sabre wounds, six bayonet wounds, and two gunshot wounds), from which, after severe and protracted suffering, he has barely recovered. His conduct was so conspicuous, and his cool bravery so much admired, as to elicit the praise of the enemy and even of General Sherman himself.

Anderson had to know that his position had no hope of reinforcement from Hardee’s troops inside Savannah, nor did he have any real chance of stopping Hazen’s men from taking his post. However, in the archaic Southern fashion, he stood his ground and resisted until there was no one left standing. In his after-action report he noted, “The fort was never surrendered. It was captured by overwhelming numbers.”

With the fall of Fort McAllister, the March to the Sea for all practical purposes ended. By 5 p.m. Sherman was able to signal the route was clear to a navy steamer already coming up the river with badly needed supplies. Losses were high for such a short fight, with Hazen losing 24 killed and 110 wounded and Anderson losing 17 killed, 31 wounded, and all the rest made prisoner.

As soon as news reached Hardee of the fall of Fort McAllister, he knew that holding onto Savannah would be futile and began making preparations to evacuate his army into South Carolina. His engineers immediately set about making a series of pontoon bridges from the foot of West Broad Street, across the network of tidal rivers, to Hardeville on the South Carolina border. This escape route ran along the narrow top of Huger’s Causeway (roughly the route that US 17 follows today). A thick layer of rice straw was put over the wooden planks of the bridges to deaden the sound of wagon and gun carriage wheels. All was ready by December 19, and everyone impatiently awaited Hardee’s order to leave.

Meanwhile, back on the siege line, Union gunners had kept up a steady drumbeat of fire on the city since setting up on December 10. Sherman’s engineers built a series of large, well-fortified gun emplacements for the large siege cannon they expected to receive via the navy in short order, and most began settling in for what was expected to be another long stand. On December 17 Sherman sent a rather harsh note to Hardee demanding his immediate surrender, warning that he had plenty of large guns and ammunition and that unless quarter was given he would “make little effort to restrain my army burning to avenge the great national wrong they attach to Savannah and other large cities which have been so prominent in dragging our country into civil war.”

Hardee, obviously bidding for a little more time, replied the next morning that he refused to surrender, and indicated that if Sherman carried out his threats to ignore the conventions of war and carry out unrestrained rape and pillage, then Hardee would “deeply regret the adoption of any course by you that may force me to deviate from them in the future.” For the time, this was a rather crude and uncivilized exchange of threats. Both men knew it—and neither was fully prepared to back them up.

To cover up his planned movement, Hardee requested what help was available from the Confederate Navy and sent three regiments of infantry to reinforce Wheeler’s cavalry up on the line. Late on the afternoon of December 20, the Confederate ironclad Savannah steamed upriver a bit and began lobbing shells at the Union positions. As darkness fell, every heavy artillery position began shooting up what was left of their ammunition supply, heavy shells raining down with some accuracy on the Union positions for more than two hours.

While the shot, shell, and canister rounds kept the Union troops’ heads down, Hardee began his retreat out of the city. All the field guns that could be moved left first, while work gangs set the remaining boats afire at their moorings. When the big guns’ ammunition ran out, their crews spiked the barrels and watered down the remaining gunpowder in the magazines. Major General Ambrose R. Wright’s division was the first to leave at about 8 p.m., followed by Major General Lafayette McLaw’s division two hours later and Smith’s Georgia Militia at 11 p.m.

Acting as the rear guard, the Georgia State Line, now under command of Colonel James D. Wilson, stayed in their skirmish line and, along with Wheeler’s cavalry, kept up a steady fire toward the Union lines. When a signal rocket flared up about 1 a.m., both commands gradually ceased fire, and one company at a time left the trenches and quickly moved across the bridges into South Carolina. The bridges were then sunk in place or cut loose from their moorings by engineers, the last link setting adrift at 5:40 a.m. on December 21.

When all firing ceased about 3 a.m., forward skirmishers of a dozen different Union regiments cautiously moved forward and dropped into the newly abandoned Confederate positions. Sending word back of their discovery, a general advance was soon ordered, and Sherman’s “bummers” began moving east into the city itself. The advance was led by Brigadier General John W. Geary’s 2nd Division (XX Corps). About 4:30 a.m., as the last of Hardee’s men were filtering across the river to the north, Colonel Henry A. Barnum of the 3rd Brigade, Geary’s division, encountered Mayor Richard D. Arnold of Savannah near the intersection of Louisville and Augusta Roads. There the mayor handed the Union colonel a formal letter of surrender of the city, addressed to Sherman:

Savannah, Dec. 21, 1864

Maj. Gen. W. T. Sherman, Commanding U.S. Forces near Savannah:

Sir: The city of Savannah was last night evacuated by Confederate military and is now defenseless. As chief magistrate of the city I respectfully request your protection of the lives and private property of the citizens and of our women and children. Trusting that this appeal to your generosity and humanity may favorably influence your action, I have the honor to be, your obedient servant,

R. D. Arnold Mayor of Savannah

The last state to be rid of its military occupation by the Union Army was Georgia, in February 1870.

Barnum’s men continued into the city, where, as the rosy light of dawn appeared over the horizon, the Stars and Stripes were once again raised over the U.S. Customs house. Two brigades moved on east to take the newly abandoned post at old Fort Jackson. As they entered and raised the national banner on the ramparts, the Savannah, retreating downriver, lobbed a few shells their way. Union batteries returned fire, but these last shots of the campaign had no real effect on either side.

Sherman had been at nearby Hilton Head Island conferring with navy officers on the next plan of action and did not return to the city until late on the night of December 21. Making his headquarters in the large, comfortable Green-Meldrin House at Madison Square (still existent), he sent a telegram from the parlor to President Lincoln the next day:

Savannah, Ga., Dec. 22, 1864

His Excellency President Lincoln,

I beg to present to you, as a Christmas gift, the city of Savannah, with 150 heavy guns and plenty of ammunition, and also about 25,000 bales of cotton.

W. T. Sherman Major General

Sherman entering Savannah, December 21, 1864

For places to visit in and around Atlanta, see the recommendations in our chapter on Dalton to Jonesboro. We emphasize the near necessity for anyone even remotely interested in the war to visit the Atlanta History Center in Buckhead and the Atlanta Cyclorama at Grant Park.

Confederate Memorial

Located in Forsyth Park (on Bull Street between Gaston Street and Park Avenue) is the large, rather imposing monument honoring the area’s Civil War dead. This is claimed to be the largest such memorial in the South and was the most expensive by a long shot. When unveiled in 1875, the original monument showcased two statues: Judgment and Silence. The public reaction to the gaudy original was harshly negative, and the monument quickly underwent a multi-thousand-dollar renovation, unveiled again in 1879 with only a simple sculpture of a soldier on top. Used as a Union encampment during the occupation, today the park is the setting for quite a number of festivals and events.

Fort Jackson

1 Fort Jackson Rd.

Savannah, GA

(912) 232-3945

Located 2½ miles from the center of town on the (only) road out to Tybee Island, this is the oldest standing brick fortress in the United States, built in 1808. The 20-foot-high walls contained five 32-pounder smoothbore cannon, one 32-pounder rifled gun, two 8-inch Columbiads, and one 12-pounder mountain howitzer, all manned during the war by the 22nd Battalion of Heavy Artillery commanded by Major Edward Clifford Anderson (later the mayor of Savannah). A small museum inside houses displays centering on the Confederate naval history of the area, including several about the CSS Georgia, whose watery grave is marked by a red buoy about 300 yards away in the Savannah River.

The only action here during the war came in a brief 1862 skirmish with two Union gunboats and when it was fired upon by the CSS Savannah as Union troops raised their flag atop it in December 1864. E-mail for current prices before a visit, at oldfortjackson@dnsgeorgia.org.

Fort McAllister State Historic Park

3894 Fort McAllister Rd.

Richmond Hill, GA

(912) 727-2339

www.gastateparks.org/FtMcallister

This 1,700-acre park between the Ogeechee River and Red Bird Creek has two alluring identities: It’s the site of the earthen fort that guarded the southern approach to the Savannah area, and it’s a recreational area with amenities for campers and picnickers. These two attractions once existed as Fort McAllister State Historic Park and Richmond Hill State Park; in 1980 they were combined, and today the Georgia Department of Natural Resources operates the site.

Fort McAllister is one of the best-preserved earthwork fortifications built by the Confederacy during the Civil War. The site was once owned by Henry Ford, who began an extensive restoration in the late 1930s. The fort eventually fell into the hands of the state of Georgia, which restored it to near its 1863–64 appearance.

You can wander around the walls and through the interior of the fort and look inside its central bomb-proof, but be careful not to climb on these earthen structures, which are extremely susceptible to erosion from foot traffic. Take the self-guided tour of the fort and check out a 32-pounder smoothbore gun that fired red-hot cannonballs and the furnace where these projectiles were heated; the reconstructed service magazine, which held shells, powder, and fuses for the rebels’ 32-pounder rifled gun; and the fort’s northwest angle, where the 47th Ohio Infantry Regiment placed the first U.S. flag planted on the parapets.

The fort site also has a Civil War museum and gift shop containing Civil War shells and weapons; implements such as those used in the construction of the fort; artifacts from the Confederate blockade-runner Nashville, which was sunk in the Ogeechee by the Union ironclad Montauk; a diorama of the assault on the fort; and a display depicting life at the fort as experienced by its 230 defenders.

For day-trippers, the main attraction of the recreational area is the tree-filled picnic ground running along a high bluff overlooking the Ogeechee River. Tall pines and hard-woods make this a shady, serene spot for walking or sitting in a glider-type swing and watching the river flow by. You’ll find 50 sites with picnic tables and grills, a fishing pier that extends out over the river, and plenty of rustic-looking playground equipment for the kids in this area, which borders the main road leading to the fort.

If you plan on making your visit to Richmond Hill– Liberty County last longer than a day and you like roughing it, consider staying at the park’s Savage Island Campground, which has 65 campsites—50 for recreational vehicles and 15 with tent pads—all with water and electrical hookups, grills, and tables. Two comfort stations provide campers with toilets, heated showers, and washer/dryers, and the campground also has a playground, nature trail, and dock and boat ramp on Red Bird Creek.

Georgia’s Old Capital Museum

Statehouse Square, on campus of Georgia Military College

210 E. Greene St.

Milledgeville, GA

(478) 453-1803

This imposing Gothic-style building is considered to be the oldest public building in the nation built in such a style. Begun and first used in 1803, the building served as the State Capitol until 1863. The original structure was severely damaged in several post–Civil War fires and was restored to nearly original condition in 1943. Another restoration was completed in the fall of 2001.

The Gothic-style gates at the north and south entrances to the campus were constructed just after the war from bricks salvaged from the arsenal and powder magazine blown up by Sherman’s troops.

Green-Meldrim House

St. Johns Church

14 W. Macon St.

Savannah, GA

(912) 233-3845

Built in Gothic Revival style in 1853 for wealthy cotton grower Charles Green, the house was offered to Sherman for his headquarters by the owner. Green was concerned that if Sherman did not use the structure, another Union general would, and he would “suffer the indignity of such a situation.” The famous “Christmas gift” telegram was sent to Lincoln from the front parlor, where Sherman also learned of the death of his infant son Charles, born during the long Georgia Campaign. Sherman never saw his son alive.

Today the home is owned by its neighbor, St. Johns Church, and serves as the parish house. The home is open for tours. Prices are subject to change; call before visiting.

Milledgeville Visitor Center

200 W. Hancock St.

Milledgeville, GA

(478) 452-4687

(800) 653-1804

We suggest a visit here for a copy of the excellent map and guide for a walking tour of the old part of town. Trolley tours are available here, as well as information on the series of festivals held throughout the year.

Old Governor’s Mansion

120 S. Clark St.

Milledgeville, GA

(478) 445-4545

Built in the Greek Revival style in 1839, this was the home of 10 Georgia governors, including Joseph Emerson Brown, who was arrested here by Union authorities in May 1865. Sherman rolled out his bedroll on the bare wooden floor downstairs to spend the night on November 23, remarking good-naturedly how rude it was of Brown to have left before such a distinguished visitor had arrived! Group tours are available.

Savannah Visitor Center & History Museum

301 and 303 Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd.

Savannah, GA

(912) 944-0460

(912) 651-6825

Housed in the old Central Georgia Railroad Station, the visitor center is large and rather imposing, with a very helpful staff and a moderate selection of maps and brochures of local attractions. A large museum houses a nicely presented, small selection of artifacts from every phase of this city’s long history, including uniforms and equipment belonging to Savannah’s own regiments, as well as Forrest Gump’s park bench. A short film, Savannah the Survivor, gives a breathless overview of the area history but hardly touches on the Civil War period. A small bookstore and no fewer than two gift shops round out the offerings, and several tour companies load up just outside the side entrance.

Atlanta is a major tourist and convention destination, and the hospitality industry in Fulton County alone employs more than 115,000 workers and pays more than $215 million in taxes to local governments. Needless to say, just about any chain hotel or motel in every price range is readily available. The Downtown Connector, the merging of I-75 and I-85 through downtown Atlanta, is the major corridor to all the listed amenities, and a short drive out in any direction on the three highways (including I-20) is the best bet for lower-priced chain establishments at nearly any exit.

Savannah is a city of great diversity, and that characteristic holds true when it comes to the accommodations it offers its visitors. Savannah has several hotels that are large and contemporary and others that are medium-size and quaint. It has motels that are moderately priced but comfortable and others where, for a few dollars more, you’ll be awash in amenities. Many of the hotels and motels offer suites in addition to rooms with the standard two double beds or one king-size bed, and a couple of establishments have nothing but suites.

Each of the hotels and motels listed here accepts major credit cards and is wheelchair-accessible. Almost all have nonsmoking rooms, and most do not allow pets. All establishments have color cable TV; if you’re looking for premium channels, a phone call might be in order.

The in-season generally runs from mid-Mar through Oct. Some establishments decrease their rates during the hot summer months, and others jack them up on weekends, so call in advance to ascertain how much you’ll have to spend. If you’re planning to stay here on St. Patrick’s Day weekend, expect to fork out considerably more than you would at any other time of year, and make reservations months in advance.

| Best Western Promenade Hotel in the Historic District | $–$$ |

412 W. Bay St.

Savannah, GA

(912) 233-1011

This motel has been accommodating visitors to Savannah since the early 1970s. Once you arrive at the Best Western Historic District, you can park your car and leave it for the rest of your stay, according to the folks who run the 143-room motel. The Best Western fronts Bay Street, and the motel’s rear building is on the western end of River Street, placing the three-story establishment about a block from the shops and restaurants along the river and in City Market. It’s within walking distance of much of the historic district. If you want to do your sightseeing while riding, hop on a tour bus or trolley at the motel’s front door. There is a complimentary continental breakfast and a fenced-in pool for swimming and sunning on the River Street side of the property. Eighty-seven of the rooms have two full-size beds, and the rest have kings.

| The Confederate House | $$$ |

808 Drayton St.

Savannah, GA

(912) 234-9779

(800) 975-7457

One of the most romantic inns in Savannah, this 1854 Greek Revival home overlooks Forsythe Park.

| Courtyard Savannah Midtown | $$$$ |

6703 Abercorn St.

Savannah, GA

(912) 354-7878

(888) 832-0327

The Marriott’s Courtyard Savannah Midtown stands between two of the city’s busiest thoroughfares, Abercorn Street and White Bluff Road, but the three-story motel’s beautifully landscaped grounds will give you a feeling of being away from the madding crowd. The centerpiece of the motel is the tree-filled courtyard with its quaint gazebo and swimming pool. Just off the pool is an enclosed whirlpool surrounded by lots of space for lounging, and a recently renovated fitness room near the lobby sports all-new exercise equipment. The Courtyard’s large dining area, the Courtyard Café, is open for breakfast, with a full meal and continental servings available. There are 132 newly renovated rooms, including 12 suites, and all have sleeper sofas. Rooms on the upper floors open onto balconies. There are two meeting rooms, each of which can accommodate 24 persons seated at tables. Free parking is available.

| Hilton Savannah DeSoto | $$$$ |

15 E. Liberty St.

Savannah, GA

(912) 232-9000

(800) HILTONS

This 15-story hotel stands in the midst of the historic district, and the views from rooms on the upper floors, particularly those with balconies, are spectacular. The concierge floor—the 13th, numbered as such by hotel officials apparently unconcerned with superstition—offers what staff members call the “skyline view.” You’ll pay extra to stay there, but you’ll get the view, a room featuring deluxe amenities such as the Hilton’s trademark terry-cloth bathrobes, and the use of a private lounge serving continental breakfast in the morning and drinks and hors d’oeuvres in the evening. Step out on the balcony of the lounge and enjoy a panoramic look at the graceful Eugene Talmadge Memorial Bridge and Savannah’s riverfront. If you really want to stay in style, request a “corner king”—a room with a king-size bed, balcony, two large corner windows, and a bathroom equipped with a double vanity. You can dine on the premises at Beulah’s, which serves breakfast, lunch, and dinner Southern-style, and you can unwind at the DeSoto Grille, newly renovated and offering Southern cuisine. Beulah’s serves coffee, breakfast dishes, sandwiches, and salads.

The Hilton was built in 1968 on the site of the DeSoto Hotel, which was constructed in 1890 and was a Savannah landmark for decades. A sitting room off the lobby of the Hilton affords guests a glimpse of the old hotel—the walls are covered with memorabilia, including framed banquet programs from visits by several U.S. presidents. There is also a limousine shuttle service. Pets are allowed.

As a primary travel destination and a large, well-populated urban center all in one, Atlanta has more than its fair share of eating establishments. More than 7,500 exist in the 10-county metro area; with so many newly built restaurants opening nearly daily, the five major newspaper reviewers admit regularly that they can’t keep up. A fair warning, though: Nearly as many close just as quickly, which makes the eating-out scene here quite dynamic. Again, the following is a bare sample. For the best and most recently updated listings, look for a copy of the Fri or Sat edition of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, or (preferably) a copy of Creative Loafing (free), which shows up in green-colored newspaper racks on Wed. The price range in each restaurant listing gives the cost of dinner for two, excluding cocktails, beer or wine, appetizer, dessert, tax, and tip.

| Atkins Park | $–$$ |

794 N. Highland Ave.

Atlanta, GA

(404) 876-7249

With a liquor license first issued in 1927, Atkins Park has the distinction of being the oldest bar in Atlanta. It hearkens back to the age of dark, wood-paneled, beery neighborhood bars. A perennial favorite of the Virginia-Highlands neighborhood, Atkins Park offers a changing menu, including specialties such as Southern-fried chicken and Wild Georgia Shrimp and Grits, as well as pasta and burgers.

| The Varsity | $ |

61 North Ave.

Atlanta, GA

(404) 881-1706

The one and only, the Varsity is a long-beloved Atlanta institution. At the corner of Spring Street and North Avenue, the original Varsity (there are Junior Varsitys in the Cheshire Bridge Road area of Atlanta, in Norcross, and in Athens) is just across the North Avenue bridge from Georgia Tech. It opened in 1928 and claims the distinction of being the world’s largest drive-in. Every day, this single restaurant serves up to 2 miles of hot dogs, a ton of onion rings, and 5,000 fried pies. Friendly, sometimes eccentric carhops will bring your food out to your car, or you can eat inside in one of several “TV rooms.” The serving counters here are a beehive of activity; the slogan is “Have your money in your hand and your order in your mind.” The onion rings may just be the best on the planet. The Varsity does not serve alcohol.

Your taste buds will be glad they came to Savannah—but your waistline might not be. The city offers a quantity and variety of restaurants completely out of proportion to its size. The local specialties lean heavily toward seafood, naturally, with shrimp fresh off the boats a particular favorite.

| Crystal Beer Parlor | $ |

301 W. Jones St.

Savannah, GA

(912) 349-1000

We go to the Crystal for the onion rings and the burgers, which are made from fresh sirloin ground in the beer parlor’s kitchen, but there are many other selections on the menu—crab stew, shrimp-salad sandwiches, chili-dog platters, hot roast beef sandwiches, and baked stuffed flounder.

The Crystal is a local landmark, having been a favorite of Savannahians since it opened in 1933. With its high-back, padded booths and dark-wood paneling, the restaurant retains the feel of the 1930s. If you want to get an idea of what Savannah and its people were like 40 or 50 years ago, take a look at the Crystal’s walls, which bear enlarged photographs depicting those times.

Reservations aren’t required, but they’re taken and are recommended for groups of 10 or more.

| Spanky’s Pizza Gallery & Saloon | $ |

317 E. River St.

Savannah, GA

(912) 236-3009

308 Mall Way

Savannah, GA

(912) 355-3383

200 Governor Treutlen Rd.

Pooler, GA

(912) 748-8188

1605 Strand Ave.

Tybee Island, GA

(912) 786-5520

Ansley Williams, Alben Yarbrough, and Dusty Yarbrough opened the first Spanky’s on River Street in 1976, intending to bring pizza to the area. They also served burgers and chicken sandwiches at the restaurant, which is housed in what had been a cotton warehouse. According to Williams, the chicken breasts used for the sandwiches were too large for the buns on which they were served, so the restaurants sliced off the excess chicken. Not wanting to be wasteful, they battered and fried the strips of meat and sold them as “chicken fingers.” Their concoction was a hit with locals and has become a mainstay of eateries throughout southeast Georgia and the rest of the country.

The success of the River Street location led to the opening of Spanky’s restaurants in other parts of the state, and locally on the Southside near Oglethorpe Mall, in Pooler, and on Tybee Island (that one’s called Spanky’s Beachside). Williams and the Yarbroughs eventually went their separate ways, with Williams retaining ownership of the Spanky’s on River Street and the Yarbroughs remaining involved with the others.