Vicksburg: Sealing the Confederacy’s Fate

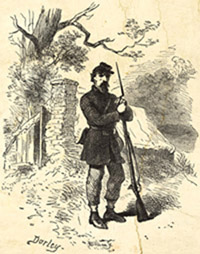

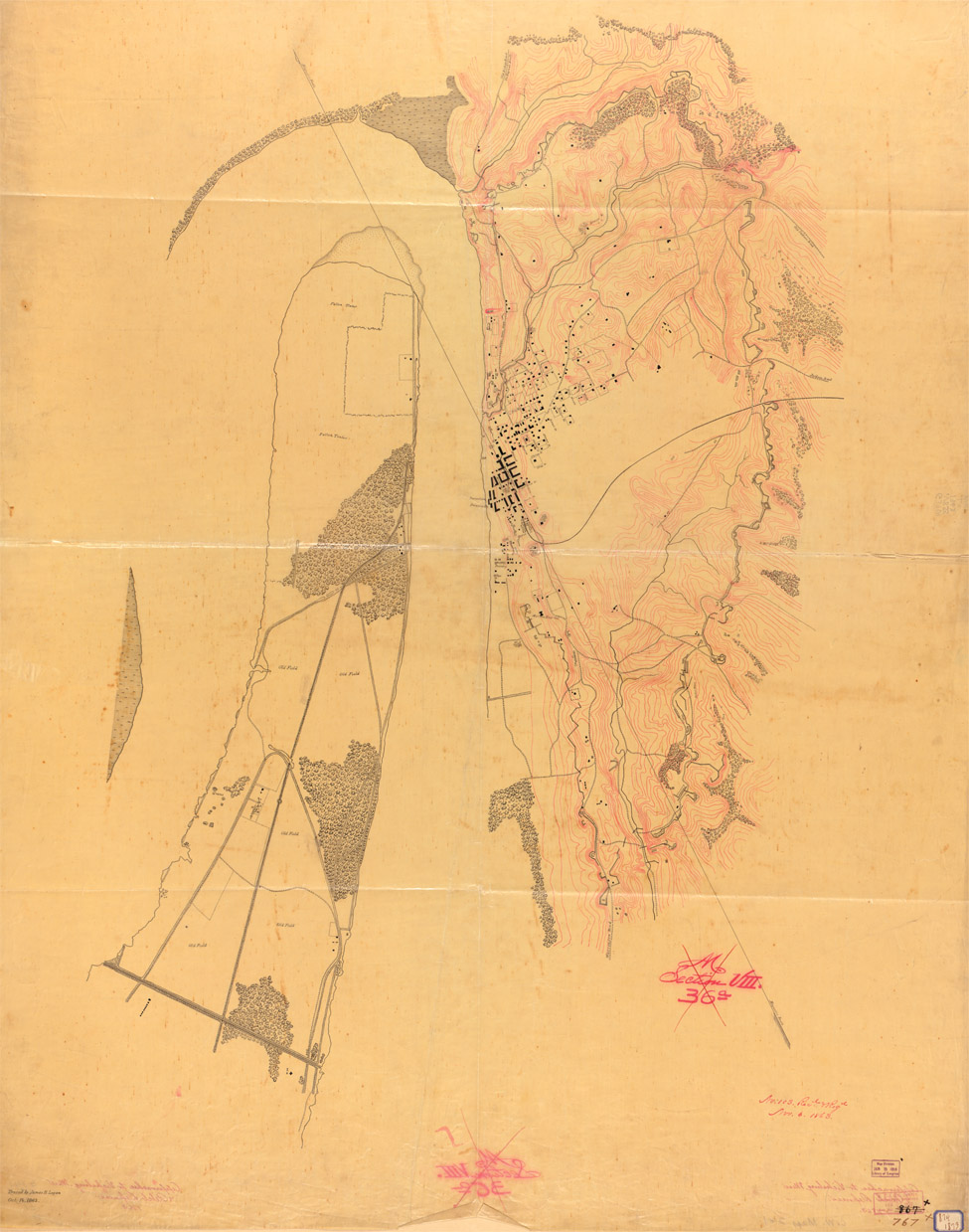

Map of the Union forces arrayed against the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg

Nearly before the first shots on Fort Sumter ended, visionary general officers of the Union Army foresaw that this would not be any “90-day struggle,” as the Washington bureaucrats and woefully inadequate top army brass claimed. Not only were the very cream of the prewar U.S. Army officer corps resigning their commissions in order to serve their Southern home states, but the level of rhetoric coming from the near-fanatical secessionist politicians ensured that once separate, it would be a long, hard climb to reconstruct the whole nation.

The de facto leader of this visionary group was none other than General Winfield Scott, the aged veteran of the War of 1812 and the Mexican-American War (not to mention his less heroic involvement in the southeastern Native American removals of the 1820s and 1830s). Despite his ill health and dated military strategies, he insisted that not only was the nation headed for a long war, but that the South could only be defeated by a long, grinding campaign aimed at cutting its lines of supply and communication. His grand scheme, dubbed the Anaconda Plan, called for an absolute blockade of the entire Southern coastline by the U.S. Navy to prevent resupply from friendly foreign countries and stop waterborne reinforcement of the Confederate armies, followed by the capture and use of the Mississippi River from Illinois to the Gulf of Mexico to cut the Southern Confederacy in half and allow it to die from lack of supplies.

“Old Fuss and Feathers” Scott’s plan was seriously derided at first, as few Union politicians or generals saw the need to do anything so drastic. The widely held belief on both sides was that one big battle would be all that was needed to send the opposing army fleeing from the field and resolve the conflict instantly. The laughter stopped, however, after the shocking Union defeat at the First Manassas (First Bull Run) battle in Virginia; and even as Scott was being replaced as general in chief by Major General George Brinton “Little Mac” McClellan, essential elements of the Anaconda Plan were being expanded into the overall Union strategy for the war.

The Union strategy during the war had three parts: first, the total naval blockade of the Southern coastline, envisioned by Scott; second, an overland campaign to capture the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia; and third, control of the Mississippi River and all the port towns along it. Brigadier General (later General in Chief ) Ulysses S. Grant opened the third part of this grand strategy in early February 1862 with the assault on and capture of Forts Henry and Donelson on the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers in northern Tennessee. With the way cleared toward Nashville and other points south in Tennessee, Grant then turned west along the Ohio River toward the Mississippi, swung around and isolated a strong Confederate garrison at Columbus, Kentucky, and then turned inland to move toward Corinth, Mississippi. Memphis fell soon afterward, after another short, fierce naval battle, completely opening the northern stretches of the Mississippi to Union control.

Major General John Pope successfully moved his Union Army of the Mississippi against fortified Confederate positions at Island Number 10 and New Madrid on the Mississippi, well supported by Union gunboats, and opened the northern stretches of the great river to Union control by early April 1862. Later that same month Flag Officer (later Admiral) David Glasgow Farragut and Major General Benjamin Franklin Butler captured New Orleans after a short naval battle, opening up the southern stretches of the river. By early spring 1862, only Port Hudson, Louisiana, and Vicksburg, Mississippi, remained in Confederate hands and prevented a complete Union domination of the river.

The Vicksburg Campaign was an unusually long and costly operation for both sides. From the earliest assault attempts in December 1862 to the final surrender on July 4, 1863, only the horrible siege at Petersburg, Virginia, from June 1864 to May 1865, was longer or more destructive in lives to both soldiers and civilians. As the best defensive ground of any port between Memphis and the Gulf Coast, Vicksburg was an obvious target that the Union commanders wasted little time in attacking.

Most histories of the Vicksburg Campaign concentrate on the famous siege of the small town, which lasted from April 29 to July 4, 1863, but in fact the battle for this critical river port started many months earlier.

Grant had been given the task of completely clearing the Mississippi of any Confederate threat when he assumed command of the newly formed Department of Tennessee on October 16, 1862. Under his command were some 43,000 men, reinforced to about 75,000 as the campaign wore on. Two days earlier Lieutenant General John Clifford Pemberton had assumed command of the Confederate Department of Mississippi and East Louisiana, which for all practical purposes simply meant the area immediately surrounding Vicksburg. The number of men he commanded has been the subject of countless debates since the war: While the force probably numbered in the 40,000 range, Grant claimed he faced well over 60,000, while Pemberton himself stated he had only 28,000.

With his victory at the Battle of Shiloh and the fall of Corinth, Mississippi, assuring his dominance over western Confederate armies, Grant immediately set about moving against Vicksburg, which he considered one of the most vital targets in the entire Western Theater. He split his command into two great columns; led by Major General William Tecumseh Sherman, the westernmost column was to move south with 32,000 men on transport barges down the Mississippi River from Memphis to directly attack Vicksburg. To keep Confederate forces divided and unable to concentrate on the city’s defense, Grant personally led 40,000 men overland south along the Mississippi Central Railroad tracks from Grand Junction, Tennessee, 35 miles west of Corinth.

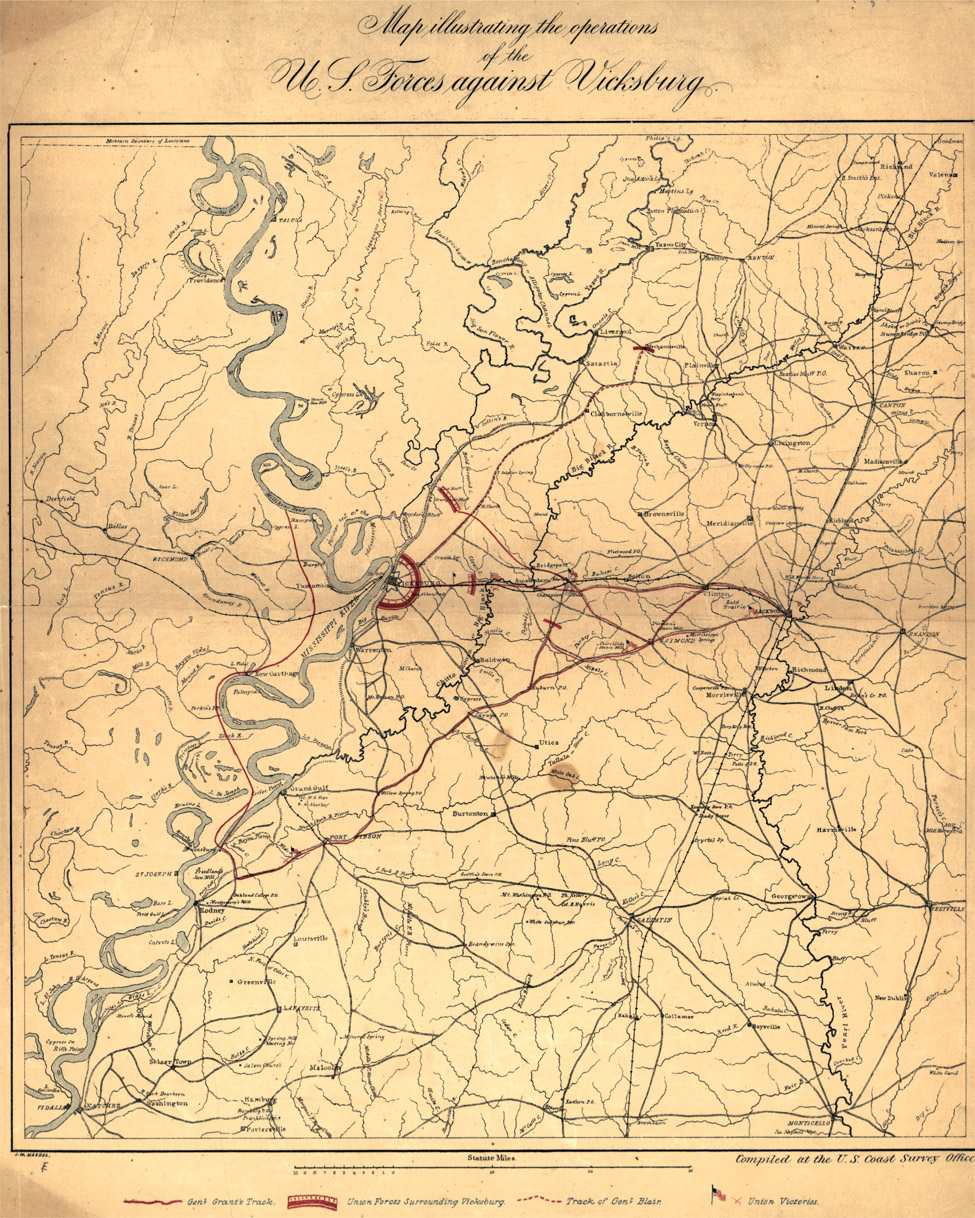

Grant moved south on November 26, 1862, slowly moving his large force through northern Mississippi. Passing through Holly Springs and Oxford, he established forward supply bases in both towns and left small garrisons to guard against expected Confederate raids. His major problem during the march south was that his supply lines back to Columbus, Kentucky, were growing longer and more vulnerable. On December 20, just as the vanguard of Grant’s column was approaching the small town of Granada, a 3,500-man Confederate cavalry force under Major General Earl Van Dorn captured and destroyed his supply base at Holly Springs. At about the same time, another cavalry force under Brigadier General Nathan Bedford Forrest stormed through western Tennessee and southern Kentucky, destroying more than 60 miles of the critical railroad lines supplying the Union overland campaign. Grant was forced to call off his part of the attack and move northwest into Memphis.

Murfreesboro, Tennessee, vicinity; men repairing single-track railroad after Battle of Stones River

The same day Grant lost his base at Holly Springs, Sherman and his men boarded a naval flotilla in Memphis and cast off toward Vicksburg. The infantrymen were loaded onto 59 transport ships and barges, escorted by 7 gunboats. A message about Grant’s defeat reached Sherman the next day, but he decided to continue on, risking that his strong surprise assault might be enough to carry the coming battle. On Christmas Eve the Union flotilla arrived at Milliken’s Bend, Louisiana, just north of Vicksburg, and prepared to start disembarking the troops.

Vicksburg had been an island of relative calm at this point, a safe harbor from the vicious naval battles that ranged north and south along the Mississippi. Social life went on, little changed from antebellum times, with frequent parties, cotillions, and afternoon barbecues—the major difference being that the men wore Confederate gray dress uniforms instead of their civilian garb. Dr. William Balfour and his wife, Emma, had prepared a grand Christmas Eve ball in their house on Crawford Street, inviting the local garrison’s officers to join the society elite in an elaborate party. As the band played and couples danced, mud-splattered Private Philip Fall burst through the door searching for the ranking officer present, Major General Martin Luther Smith, carrying the startling news that Sherman and his force were nearly upon them at that very moment. Signaling for the band to stop playing, Smith addressed the crowd, “This ball is at an end—the enemy are coming down the river, all noncombatants must leave the city.” With that, Smith and his officers immediately departed, calling out the garrison to man the defenses while still in their dress uniforms.

Aware that Sherman was coming from the north, area commander Pemberton (who arrived on December 26 from his position at Grenada) placed the majority of his men in a northeast-to-southwest line at the foot of the Walnut Hills on the north side of town (nearly directly atop present-day US Business 61 on the north side of the military park), facing northwest toward where Sherman’s troops were expected to approach. Pemberton had about 25,000 men total (including reinforcements brought in during the battle) divided into two divisions to stand against Sherman’s four divisions with 30,000 men (some sources state 33,000). The Confederate lines were formidable, with several lines of entrenchments well supported by artillery emplacements and fronted by a thick tangle of abatis made of felled trees that also gave the infantry a well-cleared field of fire.

The Union troops disembarked starting in late afternoon on December 26 and by the next day were pushing inland toward Vicksburg, led by Colonel John F. DeCourcy’s 3rd Brigade (3rd Division). As the infantry advanced slowly on the road past Mrs. Anne E. Lake’s house, they came under heavy fire from advance Confederate pickets in the nearby woods. This advance to contact ended after a brief but heavy firefight; DeCourcy pulled his men back to camp and the pickets retired within the Confederate line. Other actions took place over the next two days, while Sherman tried to figure out where Pemberton’s weakest spot was.

Finding no part of the Confederate line notably weaker than any other, Sherman decided to try a massive head-on assault. At 7:30 a.m. on December 29, his artillery opened a heavy fire on Pemberton’s line, answered quickly by counter-battery fire from massed Confederate guns on the bluff above them. About 11 a.m., Union infantry officers ordered their men into line of battle—Brigadier General Frank Blair’s brigade on the left, DeCourcy’s and Brigadier General John M. Thayer’s brigades in the center, and Brigadier General Andrew Jackson Smith leading both the 1st and 2nd Divisions on the right, all arrayed to strike the Confederate line at about the same time.

Under heavy and accurate rifle fire as soon as they exited the woods, DeCourcy’s and Blair’s brigades stormed across the bayou and managed to push through the entangling defenses and take the first line of rifle pits. Soon joined by the 4th Iowa Regiment of Thayer’s brigade (the only one to make it across the open fields), the Union infantrymen attempted to keep their assault moving and push back through the layers of defensive entrenchments, but they were soon stopped by murderous rifle and artillery fire. As they started to pull back and retreat to their encampment, General Stephen Dill Lee ordered his rebels forward in a counterattack. The 17th and 26th Louisiana Infantry Regiments surged forward, overrunning the hapless Union infantry, and soon returned with their prize: 21 officers, 311 enlisted men, and four regimental battle flags.

This scene was repeated all down the line. Although Smith’s two divisions managed to make it literally within spitting distance of the Confederate lines on the right, they were not able to carry the works even after five assault attempts. As darkness fell, the Union troops abandoned what little gains they had made and returned to their encampments. That night, during a drenching and chilling rainstorm, Sherman made plans to assault again the next day, this time aimed at taking the artillery emplacements atop the bluff, but finally he canceled the attack after deciding that it would be too costly an attempt. Another planned attack, this time against Confederate fortifications on nearby Snyder’s Bluff on New Year’s Day, was canceled when a thick fog prevented easy movement.

For twenty months now I have been a sojourner in camps, a dweller in tents, going hither and yon, at all hours of the day and night, in all sorts of weather, sleeping for weeks at a stretch without shelter, and yet I have been strong and healthy. How very thankful I should feel on this Christmas night! There goes the boom from a cannon at the front.

—John Beatty, 3rd Ohio Infantry Regiment, Union Army

Late on the afternoon of January 1, 1863, Sherman ordered his men back aboard the transport ships and barges and set sail down the Yazoo River to its mouth on the Mississippi. The next day he was placed under the command of Major General John A. McClernand, who decided to carry the battle away from Vicksburg for the time being. Sherman’s report of the battle, and his failure, is a model of terseness: “I reached Vicksburg at the time appointed, landed, assaulted and failed.” His failure cost 208 dead, 1,005 wounded, and 563 captured or missing. Despite the personal responsibility he seemed to take in his report for the failed assault, in letters and his postwar memoirs he blamed a lack of fighting spirit in his own infantry for the failure, most notably DeCourcy’s brigade, which had ironically advanced the farthest into the Confederate entrenchments. Pemberton reported a loss of 63 killed, 134 wounded, and 10 missing after the battle.

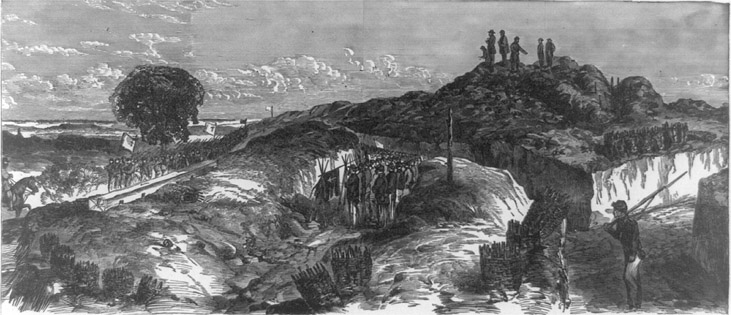

The landing at Vicksburg in 1863

Grant waited a few weeks, building up his army before attempting to reduce Vicksburg again. His major tactical problem, underscored by Sherman’s failure, was that the town was built on a steep bluff footed by swamps and the Yazoo and Mississippi Rivers, making any assault from the east, north, or south a near-suicidal venture. The only approach that might have worked was from the east, along the spine of ridges that arced nearly 200 miles above and below the town. This favorable approach had its own set of problems, most notably, how to get his troops in position atop the eastern bluffs. To add to all these problems, the winter rains that year had been unusually heavy, increasing the flooding problems and widening the rivers.

Grant’s problems can be illustrated by the near-desperate attempt he had his engineers make, digging a 1½-mile-long canal across one of the peninsulas below Vicksburg, known locally as De Soto Point, which would hopefully allow his troop and supply ships to bypass the powerful artillery batteries and land unmolested south of the city. Now known as Grant’s Canal, work continued through March of 1863, when early spring flooding destroyed some of the works and covered the peninsula and the Confederate defenders moved some of their artillery batteries to cover both ends of the canal.

Meanwhile, Major General James Birdseye McPherson was attempting to bring his XVII Corps in to reinforce Grant and hit the city from the south by cutting and blasting a passage through the labyrinth of swamps and small rivers from Lake Providence, 75 miles north of Vicksburg, to a point in the Mississippi River some 200 miles south of the city. A 400-mile-long route was mapped and partially prepared before the entire project was scrapped as unworkable.

A third attempt to gain the eastern bluffs was mounted by blasting through a natural levee at Yazoo Pass, 320 miles north of Vicksburg, and plotting a waterborne route south to the city. Before they could make much progress, Major General William W. Loring’s division rushed north to stop the Union raid. About 90 miles north of Vicksburg, the Confederate troops hastily built an earthwork and cotton bale post (dubbed “Fort Pemberton”) and engaged the onrushing Union gunboats on March 11. The Union infantry could find no way to assault the fort in the swampy terrain, and this expedition soon turned away in defeat. Less than a week later a fourth and last attempt to sail through the bayous north of the city, known as Steele’s Bayou Expedition, ended in both defeat and the near capture of all the Union gunboats.

With every attempt to bypass the Vicksburg defenses proving unsuccessful, Grant decided to take the head-on approach. McClernand had just been placed under Grant’s overall command, and he was ordered to have his command build a road to move down the western bank of the Mississippi River to a forward base directly across from the Confederate outpost at Grand Gulf, 60 miles south of Vicksburg. Planning to try an amphibious assault under fire against the Confederate fortifications, Grant also directed McClernand to have his gunboats and troop transports run past the Vicksburg Mississippi River batteries and meet up with his Army of Tennessee at a point ironically named Hard Times. On the night of April 16, 1863, eight gunboats and three transports set sail downriver under the direct command of Commodore William David Porter, each specially prepared to meet the expected hot Confederate fire. The port (left) side of each ship, which would face the Confederate batteries, was piled high with cotton and hay bales, and small coal scows and supply barges were lashed to each side of the ships.

Just before midnight the small flotilla approached Confederate outposts just north of Vicksburg, which promptly raised the alarm. Artillery crews raced in to man their guns, and within minutes a furious firefight broke out along the river. Porter reported later that every one of his ships was hit in the exchange, some multiple times, but he also stated that his own broadsides into the town could not help but do great damage to the city, as they were firing at near point-blank range. One sailor reported that they were so close that falling bricks from buildings struck by the Union cannon could clearly be heard.

Despite the heavy and accurate Confederate fire, only one transport was sunk, and the other ships limped down to join the infantry at Hard Times. Another flotilla ran the same gauntlet on the night of April 22—six transports towing 12 supply barges—but this time Confederate gunners managed to sink one transport and six of the barges.

Grant had planned to use the transports and barges to bring 10,000 infantrymen across the Mississippi to a landing point at Grand Gulf, at the mouth of the Big Black River. Porter’s gunboats opened fire on the Confederate fortifications at Grand Gulf on April 29 but failed to inflict any serious damage or silence their guns after nearly six hours of continuous bombardment. To add to Grant’s problems, return fire from Confederate gunners inflicted serious damage to the Union gunboat fleet. Grant reconsidered his plan and decided to move his men downriver to a “cooler” landing zone. The next day, in the largest amphibious operation mounted by an American army until World War II, Grant crossed the river and landed at Bruinsburg with 24,000 troops and 60 cannon. After months of campaigning, Grant at last had a toehold on the east side of the river close to Vicksburg.

While Grant was crossing the river downstream, Sherman had mounted a strong demonstration against Haine’s Bluff, while Colonel Benjamin Henry Grierson moved his Union cavalry south out of Tennessee and mounted another demonstration against the railroad lines between Meridian and Jackson before turning south toward Baton Rouge. Grant’s men began moving north almost as soon as they reached dry land, aiming for the town of Port Gibson. By late in the afternoon of April 30, more than 17,000 Union troops were ashore and moving out rapidly, with several thousand more still en route across the river.

Two Confederate brigades had already marched south from Grand Gulf to oppose the Union assault: Brigadier General Edward D. Tracy’s and Brigadier General Martin E. Green’s, which by nightfall were astride the Bruinsburg and Rodney Roads directly in the path of the Union advance. Starting about midnight the advance skirmishers of the Union column met up with the Confederate pickets, and a lively firefight broke out. The firing died down about 3 a.m. but picked up again with vigor about the first light of dawn (about 5:30 a.m.).

The Confederate lines held well until about 10 a.m., when Green’s brigade was pushed back up the road about 1½ miles by a heavy Union assault. There they were reinforced by two other brigades hastily dispatched from Grand Gulf: Brigadier General William E. Baldwin’s and Brigadier General Francis M. Cockrell’s, which helped shore up a strong line along the Rodney Road. Tracy’s men managed to hold up well in their position on the right, despite losing Tracy himself, who was killed early in the fighting. Although several vicious counterattacks were mounted that managed some limited success, the Union assault was simply overwhelming, and all the Confederate commanders began retiring from the field about 5:30 p.m.

J. C. Pemberton

The daylong battle cost Grant 131 killed, 719 wounded, and 25 missing or captured, while the Confederate commanders reported a loss of 60 killed, 340 wounded, and 387 missing or captured. Accounts vary, but the total Confederate force in the field amounted to about 8,000, while Grant had an estimated 23,000 engaged in the fight by late afternoon. Confused by the Union attacks toward Vicksburg seemingly coming from all directions, Pemberton ordered Grand Gulf evacuated and all the troops to move within the defenses of Vicksburg, instead of confronting and attacking Grant’s bridgehead.

Rather than directly move in and seize Grand Gulf, Grant decided to move northeast and cut the Southern Railroad lines between Jackson and Vicksburg, Pemberton’s only remaining line of communications, supply, and retreat. Similar to Sherman’s later march through Georgia, Grant set his forces in a three-corps-abreast formation, with McClernand’s XIII Corps on the left, Sherman’s XV Corps in the middle, and McPherson’s XVII Corps on the right. Grant planned to move nearly directly northeast toward Jackson, then turn right and cut the rail line somewhere east of the small settlement of Edwards. On May 7 the three corps moved out, a total of 45,000 Union soldiers moving deep into the very heart of the Confederacy and dangerously far from their own base of supplies.

Pemberton guessed correctly what Grant was up to and sent word to his garrison in Jackson to move out and confront the Union advance, while he moved part of his own force in Vicksburg out to strike the Union line from the west. Brigadier General John Gregg moved his 3,000-man brigade out of Jackson promptly, arriving in Raymond on May 11 and setting up pickets along the west and south roads into the town. For artillery support Gregg could boast a single battery, the three guns of Captain Hiram Bledsoe’s Missouri Battery.

At dawn on May 12, Gregg’s pickets sent word that the Union vanguard was approaching their position along the Utica Road (today known as MS 18). The Confederate commander hastily deployed his men to strike what he thought would be the right flank of a small Union force, along both the Utica and Gallatin Roads, and placed the Missouri Battery atop a small hill commanding the bridge crossing Fourteenmile Creek. As the first regiments of McPherson’s column moved into the small valley of Fourteenmile Creek, Gregg ordered volley fire into their flank.

The sudden burst of fire shattered the front Union ranks, and Gregg ordered his men to keep up a hot fire. After about two hours of volleys, Gregg ordered up his Tennesseeans and Texans in line of assault, planning to roll up the Union line and finish up the day. As the Confederates advanced into the dry creekbed and through the easternmost Union formations, they ran smack into the newly reorganized division led by Major General John A. Logan, who was leading his men into battle with “the shriek of an eagle.” By 1:30 p.m., with Union regiments and brigades piling onto the field, Gregg finally realized that he was facing a full Union corps and started ordering his units to pull back. The battle had become a confused swirling of Union and Confederate units nearly invisible to their commanders in the thick, choking dust, and it took most of the rest of the afternoon for both commanders to get a complete grasp of their own positions and issue appropriate orders.

Gregg attempted to break contact and retreat, but McPherson’s troops kept a running battle going until they reached Raymond itself. The Confederates hurried past townspeople who were preparing a “victory” picnic for them, before stopping for the night at Snake Creek. McPherson’s men broke off the pursuit in Raymond, where the Union troops helped themselves to the picnic dinner. The next morning Gregg moved his brigade back into Jackson, reporting a loss of 73 killed, 252 wounded, and 190 missing or captured. McPherson reported to Grant that he had faced a force “about 6,000 strong” but emerged victorious, at the cost of 68 killed, 341 wounded, and 37 missing or captured.

Surprised at the strong show of force so far east of Vicksburg, Grant decided that he would have to take Jackson before he could safely turn back west toward “Fortress Vicksburg.” On May 13 he ordered his army forward once again—McPherson north from Raymond along the Clinton Road, Sherman northeast through Raymond toward Mississippi Springs, and McClernand’s corps arrayed in a defensive line from Raymond to Clinton to guard against any more unpleasant surprises. The same day, General Joseph Eggleston Johnston (commander, Department of Tennessee and Mississippi) arrived in Jackson by train to assume overall command of Vicksburg’s defense. With Grant’s army nearly knocking on Jackson’s door, Johnston ordered an immediate evacuation of the city toward the north, with Gregg’s brigade and parts of two other brigades remaining as long as possible to mount a rearguard action. After a heavy rainfall in the morning of May 14 briefly delayed their attack, Sherman’s and McPherson’s corps charged the weak Confederate defenses with bayonets fixed starting about 11 a.m., driving the Confederate defenders back after a bitter hand-to-hand struggle and capturing the outer defenses of the city without much loss.

Although strong Confederate artillery emplacements delayed the Union advance in the center, Sherman sent part of his command around the right flank and north along the railroad line into the heart of the city. With his left flank breached, Gregg ordered his brigades to move out of the city along the Canton Road to the north, while Union troops invested the city right behind them. By 3 p.m. the Stars and Stripes was being hoisted again over the State Capitol building. The few hours of combat resulted in about 300 Union soldiers killed, wounded, and missing and an estimated 850 Confederate casualties.

With Grant’s army between him and Vicksburg, Johnston believed that he had arrived too late to do any real good, but he sent a series of messages to Pemberton urging him to march out of Vicksburg and join the 6,000 troops he had moved north out of Jackson in a battle to destroy Grant’s force. Pemberton, a great believer in the use of fixed fortifications, was extremely reluctant to enter a campaign of movement and maneuver. He made it very clear that he wished to remain in his line along the Big Black River, but finally he agreed to move out. In a clear act of disobedience of orders, instead of moving to join Johnston, Pemberton decided on his own to strike against Grant’s line of communication back to Grand Gulf, now occupied and a major supply center for the Union army.

On May 15 Pemberton initially moved his 23,000 men southeast to near Edward’s Station, effectively moving farther away from Johnston and placing Grant’s army between the two commands. Unknown to either Confederate commander, Grant’s men had intercepted the series of orders and communications between them, and the Union commander was maneuvering his own forces to exploit the confusion. Johnston issued another order on May 16 to Pemberton to move northeast and join him, which for some reason he decided to obey, but by this time Grant was ready to strike.

As Pemberton moved northeast early on the morning of May 16 along the Ratliff road just south of Champion Hill, his three divisions strung out along the road for nearly 3 miles, a courier brought word that a large Union contingent was bearing down upon him from the Jackson road to the northeast. Pemberton immediately halted his march and arrayed in line of battle to protect the high ground of Champion Hill itself, as well as the crossroads leading to Edwards and Vicksburg. Major General William Wing Loring’s division covered the Raymond road to the south, the right flank of Pemberton’s line; Brigadier (soon after Major) General John S. Bowen’s division deployed along the Ratliff road to Loring’s left; and Major General Carter Littlepage Stevenson’s division covered the left flank and the crest of the small knob of Champion Hill.

Just before noon Brigadier General Alvin P. Hovey’s and Logan’s divisions of McPherson’s corps attacked along the Jackson road against Stevenson’s positions atop Champion Hill. Stevenson’s men were soon forced off the crest under heavy fire, but Bowen’s division shifted north and succeeded in regaining the hill. Grant ordered his artillery massed and directed all fire on the hilltop Confederate positions, quickly followed by renewed infantry assaults. About 1 p.m. Stevenson’s and Bowen’s men were forced to retreat under the crushing Union assault, escaping south along Baker’s Creek to the Raymond road before turning west toward Vicksburg.

Brigadier General Lloyd Tilghman’s brigade was ordered to act as a rear guard, to cover the escape “at all costs.” Joined by Loring’s men, they put up a fierce resistance but were cut off by massive artillery fire and forced to move farther south and east, eventually circling around north and meeting up with Johnston near Jackson. Tilghman himself was killed during the rear-guard action.

Pemberton led his army’s retreat west through Edwards before taking up a defensive position at the Big Black River for the night, while McClernand’s corps moving in from the south entered and occupied Edwards about 8 p.m. Grant reported losses of 410 killed, 1,844 wounded, and 187 missing or captured, while Pemberton suffered 381 killed, 1,018 wounded, and 2,441 missing or captured, but the real damage was the decisive defeat of the Confederate forces. Pemberton would eventually limp back into Vicksburg minus Loring’s division, which never returned to his command, but Grant had succeeded in isolating Vicksburg to an island outpost completely cut off from any hope of resupply or reinforcement.

Big Black River battlefield

Pemberton was unaware that Loring, who had circled around to the south and east to join up with Johnston at Jackson, was not following him back into Vicksburg. Instead of immediately moving all his forces back within Vicksburg’s formidable defense, Pemberton ordered Bowen’s division reinforced by Brigadier General John Vaughn’s brigade to hold a defensive perimeter around the bridges over the Big Black River, in the hopes that Loring would soon show up and have a safe passage over the river. On the morning of May 17, with the rest of Pemberton’s troops marching the 12 miles west to Vicksburg, McClernand’s XIII Corps rapidly swept forward and engaged Bowen’s small command.

Bowen had established a seemingly tight line of battle, well anchored on the river on the left and a waist-deep swampy area on the right, with 18 artillery pieces arrayed along the line to sweep a wide area of fire that any Union assault would have to march through. Even before McClernand’s corps was fully arrayed for battle, Brigadier General Michael Lawler saw an opportunity to gain a quick Union victory and ordered his brigade to fix bayonets and hit the center of the Confederate line. In a hand-to-hand combat that lasted less than three minutes, Vaughn’s brigade broke under the fierce assault and ran for the bridges, followed quickly by the rest of Bowen’s command, as more and more Union infantry brigades fixed bayonets and followed Lawler’s lead.

Many of the retreating Confederates drowned while attempting to cross the river, forced into the water by Pemberton’s chief engineer, Major Sam Lockett, who had set fire to the bridges to keep them out of Grant’s hands. There is no known surviving record of Confederate dead and wounded in the brief battle, but Grant reported capturing more than 1,700 prisoners and all 18 artillery pieces, while suffering a total of 279 dead, wounded, and missing out of his own commands.

Burning the bridges slowed Grant’s advance less than a single day. His engineer threw up three bridges across the river by the morning of May 18, and the great Union Army quickly crossed and moved out toward Vicksburg.

Shortly after the fall of New Orleans in the spring of 1862, Flag Officer (soon afterward Rear Admiral) David Glasgow Farragut sailed his West Gulf Blockading Squadron north along the Mississippi River and captured Baton Rouge and Natchez without resistance. Joined just outside Vicksburg on July 1, 1862, by Flag Officer Charles Henry Davis’s Western Flotilla, sailing south along the Mississippi after capturing Memphis and reducing the Confederate river fleet to a shattered remnant, the two powerful gunboat fleets had managed to take control of nearly the entire river for the Union after only a few months of campaigning. Now the only thing that stood in the way of complete and free Union transit of the river, other than the weaker Confederate bastion at Port Hudson across the river in Louisiana, was a few artillery batteries stationed high on a bluff next to the river in the small but very important port town of Vicksburg.

Farragut’s fleet had passed Vicksburg several times, starting in late May, and had exchanged fire with the rapidly growing city defenses to no real effect. Before Davis’s arrival, his own mortarboats and sloops had kept a steady bombardment of the town, irregularly at first, but growing in intensity as both sides brought more guns into action. After three weeks of numbing and near-continuous fire, and after the intense heat and disease had rendered all but 800 of his 3,000 sailors unfit for duty, Farragut called off the operation and sailed south, while Davis returned his fleet to Memphis. Farragut reported that Vicksburg could only be successfully reduced by a combined army and naval force attacking from land and water simultaneously.

Confederate independence with centralized power without State sovereignty … would be very little better than subjugation, as it matters little who our master is, if we are to have one.

—Governor Joseph Brown of Georgia, in a November 1864 speech to the Georgia General Assembly

Even before the first Union assaults on the town, General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard (commander, Department of the West) had prepared a plan of defense for the town after the defeat at Shiloh and sent engineer Captain D. B. Harris south from Fort Pillow to oversee the initial construction of a series of fortifications. Major (later Major General) Martin Luther Smith soon arrived from constructing the defenses of New Orleans to take over building the Vicksburg defenses and ended up commanding troops during the siege from behind his own line of fortifications.

In September 1862, following Farragut’s failed attempts, this line of fortifications was extended to the inland side of Vicksburg, neatly surrounding the town with a powerful, near-unassailable, and continuous line of forts, infantry positions, and artillery emplacements. Within a few months the defense line ran from Fort Hill on the north side of town along the curving ridges some 9 miles south to South Fort, then back north along the river for some 4½ additional miles. The defensive line mounted about 115 heavy guns, with another 31 mounted in batteries alongside the river.

The only approaches into the city through the surrounding ridges were six roads and one railroad track that ran across natural bridges over rather steep ravines. To guard these natural avenues of attack, Harris’s engineers had built nine well-constructed and powerful forts, some with walls nearly 20 feet thick. Each one of these forts was surrounded by a maze of interconnected and interlocking rifle pits, artillery batteries, and communications trenches. In front of this line was a deep and wide ditch, and all the trees were cut down for quite some distance in front of the line to provide a clear field of fire, making any direct assault a suicidal venture at best. The town was now a massive fortified redoubt, nearly impregnable to reduction by weapons of the day, that could either prove a safe haven for its Confederate defenders or a deadly trap, depending entirely on what Grant chose to do.

A map showing the Rebel defenses of Vicksburg

Grant believed he had Pemberton’s 31,000 men demoralized and not fully prepared to make much of a fight after his two-week-long running battle from Port Gibson to the Big Black River, and he wanted to storm the Vicksburg defenses before they could recover. On May 19, with 50,000 men under his command but only 20,000 in position to strike, he ordered an immediate assault on the town.

Sherman’s XV Corps was the only command in position to strike, and about 2 p.m. he ordered a general attack. Moving against the northeastern corner of the Vicksburg line, his men attempted to storm and reduce the powerful fort called Stockade Redan. Advancing under heavy and accurate Confederate fire, part of one regiment (the 13th U.S. Infantry) got close in enough to place their colors on the exterior sloping wall before being thrown back with heavy losses. This was the only “gain” Sherman managed before withdrawing; McPherson’s XVII and McClernand’s XIII Corps made some demonstrations against other parts of the line, but neither did any better than Sherman, who lost nearly 1,000 casualties to no gain.

Three days later Grant ordered another assault attempt, this time preceded by a four-hour-long artillery barrage against the Confederate line followed by a 45,000-man attack against a 3-mile front. Portions of all three corps managed to make it to the base of the Confederate defenses, but only one regiment penetrated the line. An Iowa regiment of McClernand’s corps led by two sergeants shot their way into the Railroad Redoubt through a hole made by their artillery and in a fierce firefight managed to kill or drive out the Confederate defenders. Before this regiment could be reinforced and the breach in the wall exploited, men of Colonel Thomas N. Waul’s Texas Legion counterattacked and regained the fort. No other Union gain was made before the entire assault line was once against thrown back with heavy losses.

Pemberton had managed to rest many of his combat troops even during these assaults, using only about 18,000 of his men in the defense while inflicting a total of 3,200 Union casualties. Pemberton’s casualties in these assaults are not recorded but were undoubtedly much less severe than Grant’s. With his powerful assault forces turned aside without much difficulty, Grant changed his plans and settled in for a long siege of the fortified town, something Johnston had already warned Pemberton would be inevitable and disastrous if he pulled his forces back into the city as planned.

Grant officially began his siege operation on May 25 and, with the exception of two isolated events, made no further attempts to take Vicksburg by force. With all lines of supply, communications, or reinforcement successfully cut, Grant directed his engineers and infantry to begin construction of a series of siege trenches, designed to gradually grow nearer and nearer the Confederate positions. He had no intention of simply allowing Vicksburg to starve itself out, at least initially, but planned to try digging a series of mines (or tunnels) under the massive fortifications, pack them full of explosives, and literally blast his way through the walls into the city.

While the infantry was busy digging their way through Mississippi, Grant’s artillery and Porter’s naval flotilla set about making life miserable within the town. While the city had suffered sporadic shelling from Union gunboats on the river ever since the first days of the campaign, nearly constant incoming fire began soon after Pemberton brought his army inside the defenses and did not cease until the final surrender some 47 days later. It did not take long for Vicksburg’s citizens to move out of their homes and into caves dug deep into the sides of the hills. It also did not take long to figure out when they could safely venture out to try to find food and water: 8 a.m., noon, and 8 p.m., when the artillerymen would cease firing to eat their meals. Grant continuously built up his siege artillery force, and by the end of June he had 220 guns of various sizes engaged around the city.

Within a relatively short time, the siege made life nearly untenable for civilians and soldiers alike within the city. Food supplies had not been abundant when the campaign began, and when all supply routes were cut, what few items were still available commanded premium prices. Flour sold for as high as $1,000 per barrel, molasses for $10 per gallon, spoiled bacon for $5 a pound, and what little cornmeal remained went for $140 per bushel. Beef, coffee, sugar, bread, and even horse or mule meat was nearly nonexistent. For a while a bread made of ground peas was available, for a price, but soon even this disgusting fare was gone. Some accounts even claim that the rat population of the city nearly disappeared by the middle of June, but this is undoubtedly an apocryphal tale. The truth, however, is just as stark: By late June the average soldier ration consisted of one biscuit, four ounces of usually rotted bacon, peas, and sometimes a little rice each day—less than half the normal combat ration.

One odd shortage that reared its head in June was that of cartridge bags for Pemberton’s remaining heavy guns. These bags were made of flannel and held a measured charge of gunpowder, and not a single bolt of the cloth could be found anywhere in town. The soldiers were being asked to give up their outer shirts for the cause, and when the ladies of the town found out, they immediately volunteered their petticoats. A newspaper-man in town later remarked that every outgoing shell from the city’s 10-inch Columbiads was powered by these women’s underwear.

Only two days after the siege operation began, Sherman displayed his usual impatience and requested help from Porter’s naval flotilla to reduce the fortifications before him. The gunboat Cincinnati was reinforced with heavy logs and bales of cotton along her ironclad sides and then moved downriver to directly confront the river batteries below Fort Hill, clearing the way for the infantry to move in.

The Cincinnati’s captain, Lieutenant George M. Bache, brought her downriver on May 27 and turned close to shore on the north end of town to prepare to open a broadside fire on the Confederate batteries. However, before his guns could open fire, the swift river current caught his boat and spun it around, forcing Bache to unmask his stern batteries in order to maintain control. This was the weakest and least-armored section of the ironclad, and the Confederate gunners took full advantage. From atop Fort Hill and from the multiple batteries along the river, rains of 8- and 10-inch fire raked the Union gunboat, soon smashing through her stern and shooting away her steering gear. Within minutes the huge gunboat was an uncontrollable mess of smashed gun decks and wounded and dying men.

Bache attempted to run his boat aground on the far side of the river to allow his crew to escape safely, but the boat was too badly damaged to stay afloat that long. The Cincinnati went down in 3 fathoms of water, taking 40 of her men with her, her colors still flying from the blasted stump of a flagpole where they had been nailed during the brief but vicious battle.

From the very start of the siege, Grant had planned to try to blast his way through the Confederate defenses by using mines, and by late June the first were ready to go. A tunnel had been dug under the 3rd Louisiana Redoubt, near the center of the arcing Confederate line, and filled with more than a ton of gunpowder. On June 25 the mine was ready, and Grant ordered every gun he had to open fire all along the Vicksburg line to prevent Pemberton from shifting his forces around. At 3 p.m. the powder was fired, and with a deafening roar the entire top of the hill was blown off, opening a crater 50 feet in diameter and 12 feet deep. With nearly 150 heavy guns and every infantry unit along the line supporting, two regiments led by Brigadier General Mortimer D. Leggett charged into the breach, only to discover that the Confederates had discovered their mining attempt and moved back to a second fortified position.

From there, the Louisiana troops directed near-point-blank volleys of shot and canister into the Union infantry ranks, whose survivors were then soon joined in hand-to-hand combat by the 6th Missouri Infantry Regiment. The Illinois infantrymen attempted to stay in the crater, throwing up a hasty wall in front of them and forming in a double line of battle to keep up a continuous volley fire of their own. The Louisiana defenders responded by throwing hand grenades down into the crater, which Leggett later said did fearful damage to his surviving infantry. The firing died down after the Union infantry managed to pull back slightly and build a parapet across the crater for their own protection. Grant reported a loss of 30 men, but this is not thought to be accurate; his true loss in the short action was most likely between 300 and 400 killed or wounded. Pemberton reported a loss of 90 dead and wounded.

The next morning Pemberton’s men exploded two mines of their own on the north side of the line, near where Sherman’s troops were working on a mine near the Stockade Redoubt. No one was killed, but the Union mining operation there was destroyed. Another mine was started that day under the new position of the 3rd Louisiana Redan and fired off on July 1. This time a large number of Confederate defenders were killed or wounded in the explosion, which completely destroyed the large redoubt and blasted a hole 50 feet wide and 20 feet deep in the parapet walls. Colonel Francis Marion Cockrell led his Missouri regiment immediately forward to seal the breach, even though he was wounded by the explosion. Under extremely heavy artillery and rifle fire, the breach was gradually filled in and reinforced, although at a cost of more than 100 infantrymen during the six-hour-long operation. Grant never ordered an infantry attack forward to exploit this breach.

With mining operations continuing all along the Vicksburg line, Grant decided to hold his forces in place until all was ready, then fire all at once and assault in one huge wave over the line. By July 2 the siege trenches were so close to the Confederate positions that the defenders would only have time for one volley before the Union infantry would be on top of them. The only crimp in this plan was a possible attempt to relieve Vicksburg from Grant’s rear.

Johnston had returned to Jackson after Grant’s departure and had spent the intervening weeks building up his forces. In addition to the men he had pulled out of the capital in the face of the Union assault, he now commanded Loring’s division, joining him after being cut off from Pemberton after the Battle of Champion Hill, as well as every militia unit, local defense command, home guard, or individual able man that could be scraped together from all around Mississippi. Johnston had appealed to both Bragg in Georgia and Davis in Richmond for more troops and supplies, but the building Chickamauga Campaign in north Georgia had taken up every spare man and all the available supplies. In Jackson he had nearly 30,000 troops, but the vast majority were green troops, totally untrained and ignorant of battle, with a curious collection of shotguns, muskets, and old rifles.

Despite the odds, Johnston was determined to do what he could and sent a message to Pemberton that he was on the way and would attempt to break through Grant’s siege line, probably on July 7. Grant had intercepted this message and promptly shifted his forces around to face Johnston, who he feared far more than Pemberton, and requested immediate reinforcements from any command in the west. Several thousand men arrived from the Trans-Mississippi Theater and from Union armies in Tennessee later in June, and Grant sent Sherman to take control of the growing threat from the east.

In the end Johnston never did anything with the army he had raised, remaining in Jackson until June 28 and then hesitantly moving west. On July 4, still not in contact with Sherman’s line at the Big Black River, he learned of Pemberton’s surrender and immediately returned his army to Jackson.

By early July nearly half of Pemberton’s men were unfit to fight, suffering from malaria, dysentery, gangrene, and a host of other illnesses, and the rest capable of holding on but weakened by the severe food shortage. Nearly every building in the city had been hit by the ceaseless artillery fire, and most were reduced to blasted hulks. Snipers fired at any man who dared poke his head out of his trench or above the parapet of his redoubt; civilians were now living full-time in dug-out caves, many with ventilation so poor that candles wouldn’t stay lit. The stench from blasted-apart horses and mules filled the air, and everyone was approaching complete exhaustion from the strain of the prolonged siege.

Pemberton knew that Grant was about to make a move against him and that his men probably wouldn’t be able to stop it. Multiple communications begging Johnston to attack went unanswered or came back with replies saying the Jackson garrison needed more time to organize. In answer to Pemberton’s predicament, a letter appeared in his headquarters on June 28, signed “Many Soldiers,” praising his own inspired leadership but asking that he surrender. The letter went on to threaten a general mutiny if he did not. On July 1 Pemberton circulated a letter among his top commanders asking if their troops would be able to fight their way out of the siege, which came back with a decidedly negative answer. On July 2 he called a conference of all his officers and point-blank asked if they thought he should surrender the city. Only two disagreed but could offer no other feasible plan.

At 10 a.m. on July 3, 1863, white flags of truce were raised all along the Vicksburg line, and for the first time in weeks the guns fell silent. After some difficulty in discussing the terms of surrender, with Pemberton showing some late-stage theatrics and Grant calmly insisting upon unconditional surrender, a deal was finally struck late in the day. Confederate soldiers would surrender their weapons but would not enter prison camps, instead being paroled as soon as rolls could be made out. Grant wanted to avoid the expense and logistical nightmare of feeding and transporting 30,000 prisoners, and Pemberton found the offer quite acceptable, undoubtedly knowing that most of the men would soon return to the army anyway.

At 10 a.m. on July 4, 1863, the day after the great Union victory at Gettysburg, Pemberton ordered each of his divisions in turn to get out of their trenches, form up, and march under their own colors to the surrender point. Union regiments stood alongside the road watching silently as their beaten opponents passed, offering in a soldier’s way a salute to the gallant defenders of Vicksburg.

With the Confederates stacking arms and tenderly laying down their colors, Major General John Alexander Logan led his 3rd Division into the town to occupy it, and soon one of his regimental flags and the Stars and Stripes were raised over the courthouse. The long campaign was at last over, and the end of the Confederacy in the West had begun.

Soldiering is a rough coarse life, calculated to corrupt good morals and harden a man’s heart.

—Private Henry W. Prince, 127th New York Infantry, Union Army

Siege of Vicksburg, Surrender, July 4, 1863

Both sides suffered terribly in the long campaign to capture Vicksburg, and, ultimately, the Mississippi River. There are fairly complete records for Grant’s losses: 1,514 killed, 7,395 wounded, and 453 captured or missing. Confederate records are very spotty on this period, but during the siege operation alone Pemberton lost a reported 1,260 killed, 3,572 wounded, and 4,227 missing or captured. Union records indicate that a total of 29,491 surrendered on July 4, but this figure includes all the civilians left in town as well as the remnants of the Confederate defenders.

Vicksburg lies 45 miles due west of Jackson, Mississippi, easily accessible on I-20. The battlefield park lies just off I-20, exit 4; turn right at the bottom of the exit ramp (approaching from Jackson) onto Clay Street, and the well-marked entrance to the park is just ahead on your right. The main business district of Vicksburg is farther west along Clay Street, which is dotted with directional signs to guide you to all the prominent and most of the obscure sites and attractions. The Vicksburg Convention & Visitors Bureau Welcome Center is across the street on the left from the battlefield park entrance and is a must-stop for detailed directions, as well as the vast selection of brochures, discount coupons, maps, and other information on the local establishments and attractions. The staff is quite friendly and has demonstrated an outstanding willingness to go far out of their way to help meet visitors’ needs.

Almost all of the Chickasaw Bayou battlefield is now private property and not open to touring, but you can get a good view of the area from a highway that runs through the area and from certain points in the battlefield park. US 61 Business, also known in town as Washington Street, runs northeast out of town, and just past the boundaries of the battlefield park it passes over the remains of the Confederate line of defense. About 1½ miles north on US 61 Business is a turnoff to the left leading to an old Indian mound; this was the position held by the 31st Louisiana and 52nd Georgia Infantry Regiments, supported by a battery from the 1st Mississippi Light Artillery, which successfully held off five strong assaults by Union troops.

One of the best views of the general area can be had from Fort Hill, within the battlefield park (Stop 9 on the tour map). From the north ramparts, look straight ahead and a bit to your right: The bluffs you can see about 2 miles away are the positions of Confederate artillery during the battle. The Confederate infantry was in emplacements at the base of the bluffs, and the swampy area you can see a little to your left is where the Union troops assaulted through.

Today Vicksburg is a bustling small town, driven in about equal parts by Civil War–related tourism and the new boom in riverboat gambling. As you drive down the “main drag,” Clay Street, you can’t help but notice the extreme frequency of markers and monuments scattered among the fast-food restaurants and small businesses. Even many of the businesses completely unrelated to the Civil War make some reference to the long siege and battle in their names: the Battlefield Inn, Vicksburg Battle Campground, the Pemberton Square Mall, and so on. Although obviously the destination at the end of a well-worn path leading hordes of tourists from Jackson and other points east (and west and north and south), it is a surprisingly pleasant place to visit. Unlike our stops at a great number of other tourist and Civil War–related destinations, we did not have a single unpleasant encounter during our visits, and aside from a few government employees in the national park, we experienced nothing but the warmest and most gracious of welcomes wherever we went.

This no doubt was the result of Vicksburg’s “other” and perhaps least obvious face: that it is ground zero for that most revered of all surviving Southern traditions, the Southern belle. Scarlett O’Hara of Gone With the Wind fame is the idea that most people not of the South have of belles, and in some ways it is an accurate portrayal. Belles are known here (and across the Old South) as an effective combination of sugar-sweet politeness covering the tenacity and effectiveness of a tank, women who would never think of being rude to a stranger any more than they would wear white shoes before Easter (or after Labor Day, for that matter). While some of their traditions seem a bit dated, such as never putting dark meat in a chicken salad or avoiding Miracle Whip like the plague (“real” Southern belles make their own, or at least buy Hellman’s and add a little lemon), it is an absolute delight to be in the presence of people who would never dream of making you feel uncomfortable or unwelcome. As opposed to the standards set by certain television talk shows and the average rush-hour commute, these ladies can think of no word stronger than “tacky” to describe the worst possible aspect of someone’s behavior. And they would never, ever say that to their faces.

Old times are indeed not forgotten here, as the annual Spring and Fall Pilgrimages open the many antebellum homes for tours, the fees from which help keep many of them open and in the same family. Many of these homes claim rightfully to have survived the vicious fighting here, and several have visible damage to the structure as proof. While the main visitor center on Clay Street can give you maps and brochures of the even-dozen homes open year-round for tours, some of which are listed below, a casual drive around the small city takes you past many others that wear their scars from the war as badges of honor.

One last word about touring Vicksburg before we recommend some specific sites and attractions: When you go (and you must!), prepare to stay awhile and let the charm of this Confederate mecca embrace you. This is not the sort of historic site that treats its history as a sideshow to help get you to empty out your wallet; these folks rightfully treat their town as hallowed ground, where the sacrifices of both sides are respectfully preserved and, for the most part, tastefully presented.

Anchuca

1010 First East St.

Vicksburg, MS

(601) 661-0111

(888) 686-0111

www.anchucamansion.com

Take a 30-minute tour through this grand mansion filled with magnificent period antiques and gas-burning chandeliers. Built in 1830, Anchuca was one of the city’s first mansion-type homes. Additions were made from 1840 to 1845. After his release from serving 2½ years in prison, President Jefferson Davis went to Anchuca to visit his oldest brother, Joe, who was living in the mansion, and made a speech from Anchuca’s balcony. In addition to the two-story main house, Anchuca visitors can see the original slave quarters, also built in 1830, and the turn-of-the-20th-century guesthouse. There is a five-minute video before the self-guided tour begins.

The Duff Green Mansion

1114 First East St.

Vicksburg, MS

(601) 636-6968

(800) 992-0037

www.duffgreenmansion.com

A former hospital for Confederate and Union soldiers, this three-story mansion, built circa 1856, offers 30-minute tours daily on the hour. Visitors will see what is considered to be one of the finest examples of Palladian architecture in the state. The mansion was built by Duff Green, a wealthy merchant, for his bride, Mary Lake, whose parents donated the property as a wedding gift. In a cave near the mansion, she gave birth to a son during the siege of the city and named him, appropriately, Siege Green. Before the war, the 12,000-square-foot home was the site of many lavish parties. Now it offers bed-and-breakfast accommodations. Open daily for tours, except during private functions.

Vicksburg National Military Park and Cemetery

3201 Clay St.

Vicksburg, MS

(601) 636-0583

www.nps.gov/vick

This 1,858-acre park is called the best-preserved Civil War battlefield in the nation. A trail more than 16 miles long carries one through the major sites of the long campaign here. We suggest you start out in the visitor center in order to view the 18-minute film, Vanishing Glory, and see the life-size exhibits and artifacts telling the story of the campaign. This will give you a much better bearing over the complex actions than if you simply try to drive through the park and get a feel for it yourself. After your visit to the visitor center (and be sure to walk over and see the replica artillery emplacements next to the parking lot), drive through the park’s rolling hills, past markers and monuments recounting the military campaign. The driving tour goes through the Vicksburg National Cemetery, where nearly 17,000 Union soldiers are buried. Also in the north section of the park are the remains of the Union gunboat USS Cairo and its adjacent museum. Hours vary by season.

The main road through town and its intersection with I-20 has just about every major national chain restaurant, but for a real Vicksburg experience, we recommend you try one of the numerous local establishments dotted around town; check at the city visitor center for an up-to-date listing.

| Gregory’s Kitchen | $ |

815 US 61 N. Bypass

Vicksburg, MS

(601) 634-0208

(877) 634-0208

This family-owned restaurant features all-you-can-eat Mississippi pond-raised catfish and rib-eye steaks. The menu is handwritten, and the atmosphere is homey. You haven’t lived until you’ve tried their fried dill pickles. The restaurant is open only on Thurs, Fri, Sat, and Sun.

| Rusty’s Riverfront Grill | $–$$ |

901 Washington St.

Vicksburg, MS

(601) 638-2030

You may have to get here early, as people stand in line to try the fried green tomatoes topped with lump crabmeat at this locally run establishment. The restaurant is considered one of Vicksburg’s best-kept secrets (until now).

| Walnut Hills | $–$$ |

1214 Adams St.

Vicksburg, MS

(601) 638-4910

Walnut Hills’s round tables filled with down-home cooking are well known and for good reason. A typical menu features some of the best fried chicken found anywhere, plus country-fried steak, fried corn, snap beans, okra and tomatoes, corn bread, and blackberry cobbler.

Grand Gulf Military Monument Park

12006 Grand Gulf Rd.

Port Gibson, MS

(601) 437-5911

Grand Gulf Military Park is dedicated to the former town of Grand Gulf and to the Civil War battle that took place there. The park is 8 miles northwest of Port Gibson, off US 61, and consists of approximately 400 acres that incorporate Fort Cobun, Fort Wade, the Grand Gulf Cemetery, a museum, campgrounds, picnic sites, hiking trails, an observation tower, and a number of restored buildings. The museum contains Civil War memorabilia plus antique machinery and an assortment of horse-drawn vehicles. Day visitors to the park must come into the museum to pay the admissions fee.

The Manship Museum

420 E. Fortification St.

Jackson, MS

(601) 961-4724

The Gothic Revival house built in 1857 and called a “cottage villa” will be forever known as the home of the Jackson mayor who surrendered the town to Union Army general W. T. Sherman during the Civil War in 1863. Not that the mayor had much choice, since Sherman was wont to ride his fiery trail through the South, wreaking havoc in his wake. Mayor Manship’s house-museum uses photos, diaries, and letters to interpret family activities and events of the 1800s. The Manship Museum is administered by the Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Admission is free.

Old Capitol Museum

100 S. State St.

Jackson, MS

(601) 576-6920

Mississippians are very proud of this museum. Called the Old Capitol Museum, it was built in the late 1830s and restored in 1961, and what a grand Greek Revival structure it is. It houses award-winning exhibits spanning the early days of the state’s colorful history through the civil rights movement and beyond. Plan to spend awhile here for there’s much to see and do, including a free guided tour. There’s also a bookstore and gift shop.

Ruins of Windsor

MS 552

Port Gibson, MS

All that remains today of this gracious mansion 10 miles southwest of Port Gibson is 23 columns. A flight of metal stairs found intact here is now at the Oakland Chapel at Alcorn State University. The mansion, completed in 1861, was a Confederate observation post. After the Battle of Port Gibson, it was turned into a hospital to treat Union soldiers. The grounds are generally open year-round during daylight hours. If the gate is locked, you can walk the 150 yards from the road to the ruins, but keep an eye out for hunters during deer-hunting season (late Nov through late Jan). There have been a few isolated instances of illegal hunting near the ruins, and illegal hunters aren’t mindful of tourists. Admission is free.