LAT 48˚55´16˝ N, LONG 123˚32´28˝ W

ACCESSIBILITY [2] Still Easy

GETTING THERE Amphitrite Point Lighthouse is quite easy to get to, though it calls for a drive to Ucluelet on the west side of Vancouver Island. If you’re visiting the coast and want a trip with unending scenic rewards, this drive is just the ticket. The paved highway (No. 4) begins about ten kilometres north of Nanaimo. It’s well marked and heads west through Port Alberni to Ucluelet and Tofino. Ucluelet is much less touristy (and much cheaper) than Tofino, and you might consider staying on board the fully restored Canadian hydrographic survey vessel, the Canadian Princess (previously called the William J. Stewart), which is moored here. The Canadian Princess is a bit funky (no TV, and the “head” is down the hall), but it is marvellously authentic and has a great on-board restaurant and bar. Once you see the ocean, you might decide to stay an extra day and walk Long Beach at nearby Pacific Rim National Park Reserve.

There’s a trail in town to the Amphitrite Point Lighthouse from the middle of town. Drive south along Peninsula Road and turn right (west), on Coast Guard Drive. The trail at the end of the road is marked.

THE WEIRD

FROM THE DAILY COLONIST: Without benefit of clergy, with no priest or minister present to read the last rites over the bruised bodies, the remains of the seamen of the wrecked, steel barque, Pass of Melfort, whose bodies were recovered from the sea, were laid away in the little village graveyard at Ucluelet while the assembled knelt and offered a prayer for the dead.

In Memory of the Lost.

Harry Scougall, Capt.; W. Baldwin, Hans Meyer,

L.B. Brown, George Planders, Charles Hayes, E. Crawford,

J. Liva, L. Bruce, J. Kern, J.H. Jopling, E. Weijonen, F. Swenson,

G. Abraham, John Kirchman, D. McInnes, W. Wormell,

G. Hardwick, G. Phillips, R. Sharpie, John Seaton, D. G. Retrie,

A. Grant, F.G.G. Richer, A. Kipling, Dan Rosette,

Thom Kelly, and one unidentified woman.107

The Pass of Melfort was a big ship, a barque of 2,346 gross tons, over ninety-one metres long. It was built in Scotland in 1890 and one of the last “moonrakers” of her time. Its three high masts were square-rigged; its fourth, the mizzen, was rigged fore and aft, and, like its sister ships, it could really move, making Cardiff, Wales, from Lima, Peru, in fifty-eight days. The Pass of Melfort was last seen by Captain Olsen on the Brodick Castle off southern California. Flag-semaphore communication established she was twenty-three days out from Panama, bound for lumber in Puget Sound. Captain Olsen expected the ship would arrive before him, but secretly he feared the worst.108

It is thought that the squat reinforced-concrete tower could survive any tsunami.

The worst happened on December 23, 1905. A horrific southeast storm drove the Pass of Melfort onto a reef on the lee shore of Vancouver Island forty-five metres from Amphitrite Point. An old salt, Captain Olsen reported that he nearly lost his Brodick Castle in that same storm. “It was the toughest bit of sailing I’ve ever done,” he said. Local First Nations told of rockets being fired from the doomed ship at dawn, and villagers from Ucluelet found splintered wreckage in a rock-strewn bay at the point. Everyone on board perished.

Men stood in the still-boiling surf all day with long boat-hooks retrieving bodies as they rolled back and forth in the waves. One still bled from gashes to the skull. Another was that of a teenager, presumably an apprentice. A woman, still wearing a new grey-cloth coat with red trim, was presumed to be the captain’s wife.

Like the wreck of the Valencia, it took the tragedy of the Pass of Melfort to get a proper lighthouse at Amphitrite Point, and even then it didn’t come easily and it took many years.

THE NAME Ucluelet means “people of the safe harbour” in the Nuu-chah-nulth language. The village of Ucluelet stands at the southern end of a long peninsula bordering the northwest side of Barkley Sound on the west coast of Vancouver Island. For generations, First Nations set out from Hitacu, a village opposite Ucluelet, venturing far out into the open Pacific to hunt migrating whales from their revered and seaworthy canoes.

The British renamed the place Amphitrite Point after HMS Amphitrite, a three-masted Royal Navy gunboat that was stationed in Esquimalt from 1851 to 1857. In Greek mythology, Amphitrite was the wife of Poseidon and goddess of the sea. The Greeks clearly understood human frailty and the supremacy of Fate.

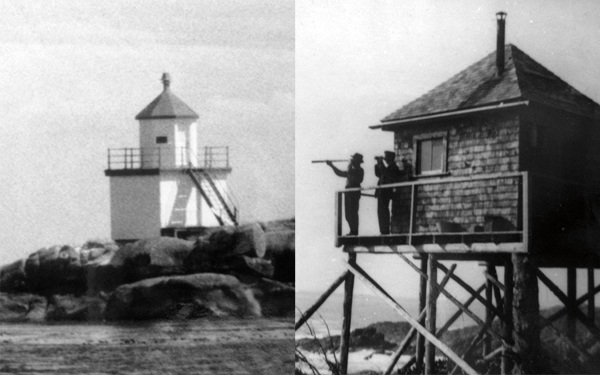

left Amphitrite’s first concrete tower (1916), and its predessesor, a temporary lookout tower (right) built after the original lighthouse was washed away in a tsunami on January 2, 1914.

CITY OF VANCOUVER ARCHIVES

DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION It was believed that the whistling buoy marking the reef in Carolina Channel had been ripped from its chains during the storm, so sailors naturally demanded a proper, shoreside light station. In response, the federal government spent a measly $140 to build a small square tower at the point housing a three-wick, thirty-one-day Wigham oil lamp. James Fraser, a coxswain from the coast guard station at Ucluelet, had the extra job of attending the lamp daily. That original tower lasted only until January 2, 1914, when a tsunami smashed it to pieces. Hastily the government built another cheap square wooden spotting tower a little farther back from the point, and it hung a smaller replacement lamp inside.

THE KEEPERS The public demanded more, and finally in January 1915, construction began on a six-metre-high squat, round concrete lighthouse, with a flashing (rotating) white light and foghorn. The whole stubby structure was firmly attached to a blasted-flat rock base at the point. Yet, even then, the tower had no dwelling for a keeper, and for three years the coast guard had to manage the light. By 1918, the coast guard was fed up with the extra work and the government took on the coxswain and made him Amphitrite’s keeper.

But James Fraser couldn’t live at the station, as there was no accommodation. So he was required to walk from town, each day—at dusk to light the lamp and again at midnight to rewind the rotating mechanism, walk home, and return twice again before the morning’s hike out at dawn to extinguish the wick. He did this for 365 days, sleet, hurricanes, and torrential rains be damned. For his trouble, he was paid $10 a month. He quit a year later, in 1919.

His replacement, Fred Routcliffe, squeezed a bed into the tower beside the noisy diaphone apparatus and resigned himself to such an existence for ten years. He complained finally, stoically, arguing that it was just the leaks and the damp during the rains that made the place unfit.109 Eventually, in 1929, the Department of Marine built a keeper’s house well behind the tower and, wonder of wonders, even equipped the place with a telephone.