2

INTO RUSSIA’S REALM

Over the centuries, soldiers’ boots have tramped back and forth over what many through the years have called the Heerweg – the military way across the flat plains of northern Europe from the Channel into the fastnesses of western Russia. Further south, the Fulda Gap, through which NATO planners expected a hypothetical Warsaw Pact armoured invasion, was the other way through. So were other gaps out of the Czech lands. The Expedition Kombis, in their baptismal ride, like a pair of Valkyries, took first the southernmost road through the Erzgebirge, before striking east down into the great northern plains and the long, boring and often desolate highway stretching as far as the eye could see. It was nearly 3,000 miles of historical road from Cambridge to Moscow.

Before finally escaping the clutches of Ostend, Tony reluctantly forked out $490 in greenbacks for a customs bond to repossess the container-load of equipment. Some seemingly arbitrary items were rebonded with a lead seal – presumably so that they could not be sold in Belgium. This bureaucracy, together with the need to divide all the stores into roughly equal portions and load the two apprehensive Kombis, delayed things further. At the Belgo-German border, the Germans refused entry because it was then half-past midnight. One forgets now just how closely in 1961 borders between European states were controlled. Cameras, for example, were taxed differently in different countries; one had to carry receipts of purchase. Lorries needed manifests which were checked at each customs post. The Expedition’s ‘cargo’ of camping equipment, food and sundry supplies, exposed it to inspection at all borders – and customs officials did not work a 24-hour shift in those days. Sleeping bags, it turned out, were part of the newly bonded equipment and so everyone spent a very cold night in the Kombis on the Belgian side of the border.

The next day dawned, and the little convoy went straight through German customs thanks to fast talking by Mehmed with his good Teutonic language skills gained from an in-service traineeship with Siemens. Tony, all six foot plus of him, hovered over the little Belgian customs man and got his $490 back – in Belgian francs.

More photo equipment was picked up in Bonn where it was much cheaper to buy than in England with its exorbitant taxes. Then on to the Turkish ambassador’s residence in Bad Godesberg for an excellent lunch to replace the sabotaged engagement dinner. While Mehmed stayed behind to sort out his ‘marital’ problems, the rest of the team crowded into ‘Tim’s’ Kombi to drive on a big detour to Adelsheim, east of Heidelberg in the hills of northern Baden-Württemberg, the home of a very distinguished patron of the Expedition, the Baron Ernst von Adelsheim.

Tony had been given a lift by the Baron whilst hitch-hiking in a kilt from London to Istanbul via Denmark a few years earlier. The Baron, intrigued by this phenomenon, had asked Tony to stay with him for a few days and explore the 5,000-acre estate at his sixteenth-century century Schloss.

The Kombi and its crew eventually arrived at 11 pm, to be offered chilled white wine served by white-gloved servants, and then given dinner in the hall by a blazing fire. All went off to bed a little the worse for wear. The next day, the Baron lavished grand hospitality on the team, followed by a drive around his estates and a walk to the Roman wall on one of the estate boundaries. It was at the limes – boundary – of Roman expansion into Germany. After dinner the Baron’s son Cornelius, due soon to go up to Cambridge, and a friend, gave an impromptu recital of flute and cembalo. It was a last touch of civilized living until an evening at the Bolshoi in Moscow.

Peasants going to work in their horse-drawn, wooden trailers gave some colour to an otherwise uneventful journey through Germany the next morning. In Nürnberg Tim, the ever-prudent engineer, had the Kombi given a last check-over by the local Volkswagen garage. Tony, meanwhile, was back in Bonn meeting Mehmed and Traicho, and collecting the other Kombi which had by then been repaired to an almost new condition after its abusive treatment in Mehmed’s nervous hands. A little later the duly repaired Kombi and its crew also reached Nürnberg, but this time with a punctured tyre. Mehmed and company called for a mechanic to do the job – after they had tried asking for help from the police who did not quite appreciate the joke. Or was it a joke? With the benefit of hindsight one can only goggle at why a Bulgarian, an Englishman and a Turk, destined for an expedition to faraway places, thought it wise to call for the German police just because their vehicle had a puncture. The learning process was well under way.

Arriving at about 9.30 pm at the German/Czech border, the first Kombi found another frontier that it was too late to cross. The German frontier officials suggested camping behind their station, with use of their washing facilities, and suggested a place to put up a tent. This was duly done – it was the first time. Nigel, Peter and Roger squeezed into the tent. All was calm until in the small hours it began to blow and rain, and the tent collapsed. Tim, sleeping in the Kombi, stirred briefly and just laughed. The doleful apprentice campers listened to sporadic bursts of gunfire during the night from the Czech side – never explained – and began to wonder what was in store for them.

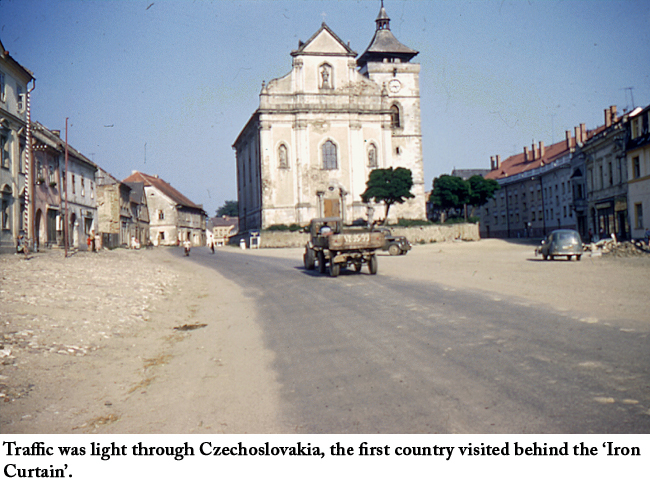

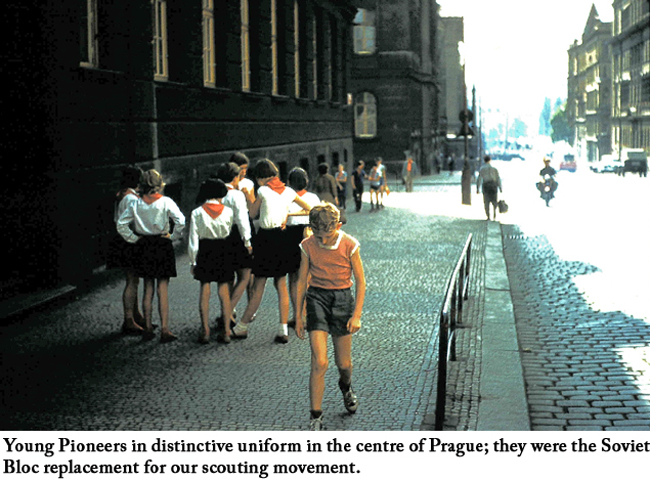

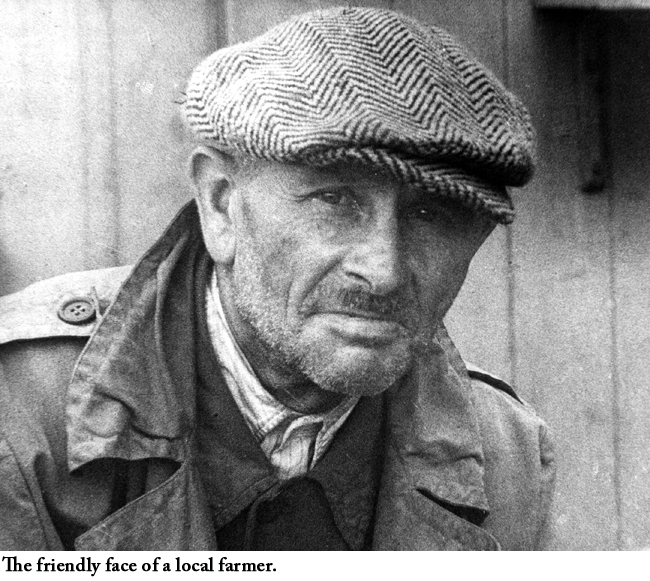

At the Czech border post the first Kombi to cross had to pay for a Czech carnet travel document – funnily enough the second Kombi did not. Now the Expedition was finally behind the Iron Curtain. In the morning, more peasants’ carts crowded the road. The surface was passable; a few six-wheeled lorries made up the industrial traffic. Driving straight through Pilsen – not even time for a glass of the celebrated beer – a brief stop was made in Prague, where the buildings still had many scars from World War II shelling, before pressing on over flat countryside to the Polish border. Another bureaucratic delay ensued, but with the help of a Polish couple returning from holiday who spoke English, a free carnet was obtained. Once over the border, the time came to cook a first big meal with ingredients from all those supplies cramming the Kombi space; a first experiment, too, with the state-of-the-art camping stove wheedled out of a supplier. Coming to terms with accelerated freeze-dried meat was another first – it tasted like chewed cardboard. Over the months ahead, experience would refine the basic recipe until a passable bolognese sauce of some kind was produced as a suitable accompaniment to the half hundredweight of spaghetti that each vehicle was carrying.

A rough and treacherous road brought the Expedition driving through the night to Wroclaw, the former Breslau. Every town or village passed through was paved with treacherous cobblestones. It rained non-stop – a miserable night’s driving. Stopping in the early morning by a café, with no local money, a tin of Nescafe and 40 cigarettes plonked on the counter was rewarded with a good hot Polish meal for four. Mehmed exchanged a sixpenny bar of chocolate for 40 litres of petrol.

On the road further east hundreds of people in the small town of Miedrzyrzec were crowded together in the market – a most extraordinary and colourful spectacle after the long drive through the dreary Polish plains. A weekly rural gathering, like anywhere in Europe, the roads thronged with typical farmers’ transport – a horse-drawn, rubber pneumatic-tyred cart, with people sitting on a pile of straw. Peter and Nigel bought potatoes, and talked in Anglo-Polish-broken-German with the locals. Then, direction Minsk, on to the border itself at Brest-Litovsk, where the Russians staged a thorough customs inspection. Fresh, unpeeled produce was not allowed through so Peter, impeccably groomed as ever, proceeded compulsorily to peel the newly purchased potatoes and carrots in full view of the Soviet officialdom. The underside of the vehicle was carefully examined by the frontier guards – something that happens routinely now, but was most unusual in 1961. It was also made clear that the death penalty for currency smuggling had just been introduced – no one had yet read the story of how that came about in Hustling on Gorky Street written by a Russian refugee in New York. Everyone had roubles: Mehmed looked at the sky and put at the back of his mind the fact that Traicho entered the Soviet Union with 2,000 roubles in his pocket.

Between Brest and Smolensk the top gear in Z1235, ‘Tim’s Kombi’, suddenly decided it was fed up, went on strike, and the gear lever jumped out. Nothing could persuade it to stay in other than jamming it in by hand and holding it there. Fiddling with the linkage achieved nothing. Tim finally fixed up an arrangement of his own making with string and a clamping wrench, which allowed third gear to be selected with reasonable ease. All that was missing was sealing wax. The Kombi complied.

After a breakfast of porridge – the first of many – it was time to soldier on along roads which, since Wroclaw, through Minsk, just went straight for mile after mile across the great plains. Their surface became progressively worse towards Moscow. As traffic became heavier, the Kombi again expressed its displeasure as its fourth gear gave more trouble. As the Soviet capital drew nigh, collective farms and wooden-hutted shanty towns of agricultural Russia dotted the landscape. The inevitable policemen took the Kombi’s number as it passed.

The two Kombis had been separated in Germany. Tim, Roger, Nigel and Peter were riding in the Kombi with the intransigent gearbox. Far to the west, and a few days behind, Kombi Z1060 with Mehmed, Tony and Traicho aboard, was suffering from neglect.

On the long, straight road between Minsk and Smolensk, on a hot morning, Mehmed noticed a red light blinking on the speedometer of the Kombi. All three of them, Tony the lawyer, Bulgarian philologist Traicho and Turkish Mehmed, himself a freshly graduated Cambridge engineer, assumed long faces and frowns. They stopped, opened the engine cover and watched the engine carefully. Tony watched from a distance. Traicho, more inquisitive, did so from a closer squatting position. Mehmed decided to take a photo and let the other two (non-engineers …) solve this intriguing engineering problem. Having examined all the different parts of the engine from his squatting position, Traicho turned to Mehmed and asked seriously: ‘Pasha, how do you say “oil” in German? Is the word perhaps “Oel”?’ When Mehmed said ‘Yes’, Traicho beamed with satisfaction. ‘Here, it says “OEL”. I suppose we open the cover and pour in some oil.’ Luckily there was a spare can of oil somewhere and all this went into the engine, no one being quite sure how much oil was necessary. Obviously – as it emerged later – it was not enough. Several hundred miles later on reaching Moscow on 4 July, the Expedition had effectively burnt out its first engine.