3

SUMMER IN MOSCOW

A hill dropped behind and there lay the panorama of Moscow, glowing pink and gold in the setting sun. The university, the skyscrapers in the distance, all the landmarks stood out as if flood-lit against the darkening sky, the Moskva River a silver stripe at its feet. It was a breathtaking sight; one could have wished for no better welcome. The summer air was clean. The all-pervasive smell of lignite, so typical of much of Central and Eastern Europe, had taken a holiday together with the power stations that burned it.

Nigel had been to Moscow two years before and was supposed to navigate. Enormous changes had wrenched this great city further still from the grim destruction, dust and rubble of war. Within minutes the Kombi was lost. A lorry driver leaned out of his cab and shouted, ‘Follow me!’ After a hectic drive through the rush-hour traffic, signs to the camping site emerged on the roadside. Ten minutes later the Kombi thankfully pulled up outside the office.

These camping sites offered the best opportunities for seeing the Soviet Union. Open to all car travellers, Soviet and foreign, they were cheap, mostly clean, and spaced at convenient intervals over European Russia and the Caucasus. The Ostankino camping site was five miles from Red Square with a good bus service. The aims of the Expedition were to see some of the educational establishments for which the Soviet Union was justly famous, to meet professors and, of course, students. And there was sightseeing to do. No time was lost in getting down to business.

Moscow was big and bustling. The city council was building houses as fast as it could. New residential areas were springing up to boost the population of Greater Moscow to more than 9 million. Traditionally centred on ‘Red’, or more correctly the ‘beautiful’, Square, bordered on one side by the forbidding wall of the Kremlin and the largest state department store (GUM) on the other, streets radiated for miles, linked by so-called ring-roads.

Nigel realized that during the two years he had been away change had accelerated: the traffic had increased, the girls dressed better, the food in restaurants had improved – though not the service. He recalls the rather curious smell of Russians en masse, due to the soap they used – the only type available at the time. It was not necessarily unpleasant, just distinct. Across the city many trams and buses now operated without conductors, a prelude to the introduction of free transport. Traffic police were strict and could fine wrongdoers up to $5 on the spot for jumping a red light or taking the wrong lane. The foreigner often got away with it.

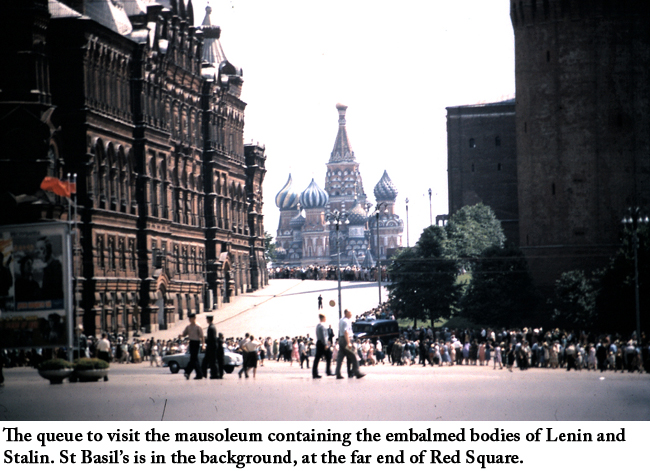

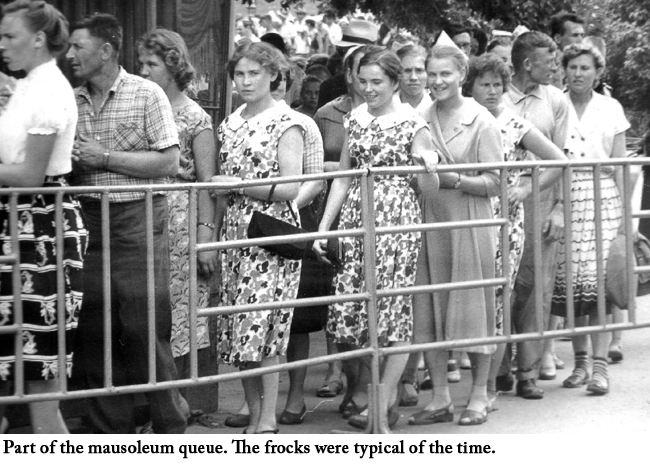

But Moscow in 1961 was still dowdy. Row upon row of vast blocks of flats created a great sameness. On first encounter the Expedition’s bushy-tailed young travellers looked at but scarcely admired the women. Clothes were drab floral prints lacking real colour in the flowers. Nobody was smartly dressed. The army and the police were among the worst – sloppy, often with a cigarette hanging out of their mouths whilst in uniform. There were virtually no advertisements; this was no Piccadilly Circus. Even St Basil’s Cathedral looked as though it needed a lick of paint. But the pavements were hosed down frequently at about 10.30 in the evening, and there was no litter. And it was compulsory to clean cars – such as there were – at least once a week. And the Moscow Metro, fantastically decorated, was fast, efficient at moving thousands of people daily – and all for the paltry price of 5 kopeks, or 5 British pennies of the time.

The British Embassy, in a splendid position overlooking the Moskva River, had superb views of the Kremlin. Christopher Mallaby, private secretary to the Ambassador, was a Cambridge friend of Nigel’s brother. Ambassador Sir Frank Roberts had been a Cambridge friend of Nigel’s father. All the right connections were nicely in place.

In Red Square, joining the mile-long queue to enter the mausoleum containing Stalin and Lenin, with women dressed in their summer frocks typical of the time, it quickly appeared that foreigners were allowed to push in only 50 yards or so from the entrance. The Cambridge visitors did just that. Both embalmed inmates looked very serene. Photography was strictly forbidden in the mausoleum. As it emerged later, the Russians enforced their restrictions on the use of cameras with grim vigour. Rumours whispered that both Lenin and Stalin’s uniforms were regularly renewed. Stalin was to be removed from the mausoleum several months later after the October 1961 22nd Communist Party Congress had rubbished his reputation for good.

This tourism highlighted the extreme contrast in architecture between the relatively colourful St Basil’s at one end of the square and the dull, monotonous apartment blocks elsewhere. It was a bit like East Berlin’s Alexanderplatz with its furbished facades and ill-kept lodgings tucked away out of sight behind. In Moscow the architect of St Basil’s had his eyes put out by the Czar so that nothing so beautiful could be built again.

The Tretyakov Gallery dazzled with its fine collection of Russian Art from the eleventh century to the present. It was most enjoyable up to the Revolution but then fell flat. The contemporary stuff could have been painted any time in the last 100 years. Peter and Roger went on to the Pushkin Fine Arts Museum with its collection of the world’s greatest art. Here Roger had a chance encounter with a blonde law student – both of them admiring Rodin’s ‘The Kiss’ at the time.

There was an abundance of attractive students in Moscow, who were very willing to meet and spend time with the Western adventurers. Peter tactfully withdrew. Somebody, however, had forgotten to tell Roger that there was little petrol in the Kombi. Roger and the young lady got less than a quarter of a mile from the Metropole hotel in the centre of Moscow before they ran out of petrol. Communication was difficult – their common language was German. They walked to the nearest filling station. Petrol pumps were usually hand-operated and the petrol was low grade, which frequently caused ‘pinking’. But Roger and Lyudmila had no petrol cans. So the petrol station lent Roger a bucket, which he filled, and duly walked through the main streets with the girl on one arm, the bucket in the other hand, hoping that nobody would think of dousing their cigarette in the bucket. Pouring the petrol into the car was the next problem. Fortunately Roger had various bits of equipment in the Kombi for developing photos – and, rummaging around, found a small funnel. Then the fun really started. They drove towards the outskirts of Moscow to a nightclub Lyudmila apparently knew. They got lost. They asked a policeman on point duty the way. Ten minutes later, appearing to have left the city behind them, they were flagged down by a police vehicle. Roger had been getting a mite concerned after earlier warnings by Intourist not to go outside the city boundaries without permission. It soon turned out that the first policeman had given them bum information; they now had new directions. Roger’s impression of Russian police went up a notch.

Eventually they arrived at this nightclub – more like a restaurant with dancing – where there was a queue. As at the tomb of Lenin and Stalin, they were taken straight to the front of the queue, as was the privilege for foreigners, and had an entertaining evening … Hours later, going back to the camp site, after taking the girl home, Roger ran out of petrol yet again. It was three in the morning. A man on a bicycle emerged out of the night; it turned out he was a bus driver on early shift. All this was conducted in sign language. Roger told him the problem. The man on the bike stood in the middle of the road and flagged down the next car to come along – a police car, as it happened. Roger spent the next ten minutes siphoning petrol out of the police car and topping up the Kombi. Roger swears that he has not run out of petrol since.

Back in Moscow, Tim asked the German Embassy what they thought of the condition of ‘his’ Kombi’s gearbox. ‘Don’t go on to Istanbul,’ they said. But no garages in Moscow could deal with the innards of a VW. Flying in spares, said the embassy trade section, would be expensive and a hassle. One idea was to nip up to Helsinki. This, however, meant having all the aggro of negotiating a new itinerary with the dreaded Intourist.

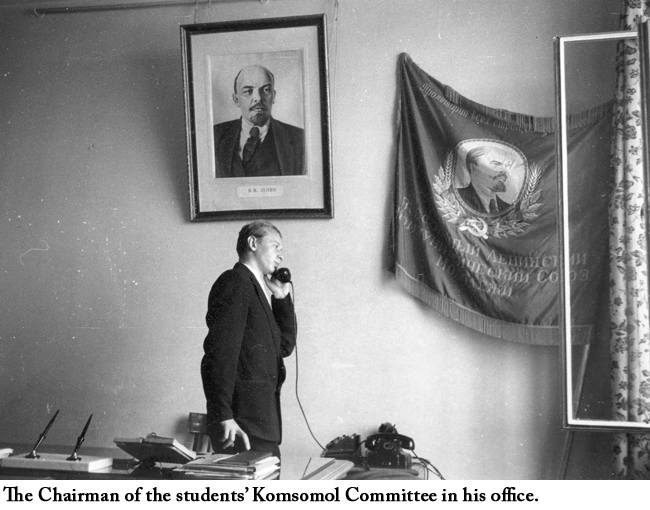

Meanwhile, more rewarding pastimes beckoned. The Komsomol was the Communist Union of Youth (ВЛKCM), for 14- to 28-year-olds. Its job was to introduce youth to politics. Some two-thirds of the then Soviet population were believed to have been members. Members received privileges and preference for promotion at work. One of the Soviet Union’s leading organizations, its control over students was near absolute, covering not only their political but their recreational activities as well. Among Komsomol officers the expedition members met were people with such varied tasks as running the institute choir and acting as representative on a final board of examiners who determined a graduate’s future work together with his or her moral fitness for the job.

The university was an extremely important institution, both politically and academically. It was the Expedition’s good fortune to meet some of the more senior students. A university student was very much regarded as a potential member of the government or of the Academy of Sciences – of the номенклатура (nomenklatura) – and as such enjoyed a high status. A meeting was set up with the Moscow Committee of the International Union of Students, actually in the bureau of the Young Communist League at the Lomonosov University, decorated with typical symbols of Communist Russia. This particular day coincided with the visit of President Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana to Moscow. The way out to the airport is the same as that to the university and the streets were thronged with crowds waiting for the signal to cheer. Police blocks were everywhere.

While in Moscow, Kombi Z1060 usually flew the Turkish flag and the Union Jack from the roof-rack. With flags aloft, therefore, the Kombi sailed through one police barrier after another, listening in vain for the resounding cheers. Evidently someone on the pavement knew his flags.>

The ‘Cambridge Capitalist Expedition’ was warmly greeted at the steps of the university by the members of the Komsomol Committee. Within minutes, all were sitting around a table dug into hard talking. The atmosphere was friendly, the opposition very sharp and the discussion never-ending. The Expedition invited them for dinner in more convivial surroundings the next evening on the sunroof at the Moskva Hotel, then thronged with Gina Lollobrigida, Elizabeth Taylor and other personalities attending the Moscow Film Festival. Somewhat flatteringly for him, Nigel, tall and with his debonair good looks waiting outside the Hotel for the Komsomol, was rushed at for his autograph by several eager Russians thinking him a Western film star. The evening was a success in that a lot of food and vodka was consumed, but the political results did not meet expectations. Many of the students, despite their privileged positions, were unwilling to commit themselves any further; only one of them turned up again. Their generous promises for dialogue of the day before had come to nothing. On the other hand, it would have been hard to find anywhere a group of such highly educated and well-informed young people. Nine out of ten were studying science, and the majority of these were on postgraduate research scholarships. All were extremely polite and friendly, and excellent speakers: a fair index of the cream of Soviet higher education.

For all the warmth, hospitality and even affection shown, official Russia in 1961 was all too ready to bully its way out of any political debate. There was an anti-capitalist argument for everything. Discussion of political subjects soon ran into a sort of dogmatic brick wall. Both sides parted from this meeting believing that the other was sincere about wanting peaceful co-existence. In itself there is nothing remarkable in this until one recalls that at the beginning of the evening Aleki, the very bright secretary of the Komsomol, was asked directly by Tony and Mehmed, ‘Do you believe in peaceful co-existence?’, and replied, ‘We do but you don’t!’ World War II still cast its long shadow. ‘Remember,’ said one Komsomolets, ‘we lost 20 million people in the war. We’re still fighting to make that up.’ It said volumes.

And yet after hours of vigorous exchanges and some tough accusations, things would return to easy conviviality. Vodka would be drunk, everyone would laugh and smoke, and then stroll together on a lovely summer evening in the university gardens in the Lenin Hills.

The university was not the only form of higher educational establishment. The majority of Soviet scientists had at one time or another passed through a single-faculty institute. One such institute was the Moscow Institute of Constructional Engineering, specializing in soil mechanics. In the laboratories the quality of the equipment and the range of the research projects was most impressive by any standards. Some ‘pure’ research projects were undertaken, but most were initiated at government demand and dealt with specific problems and bottlenecks in development. The tour of inspection was followed by tea and cakes while postgraduates delivered simplified mini-lectures on their own theses, all of which were extremely advanced. The atmosphere of goodwill, the spirit of free academic enquiry and the uproarious jokes of the host, the Chief Assistant, made this an unforgettable visit.

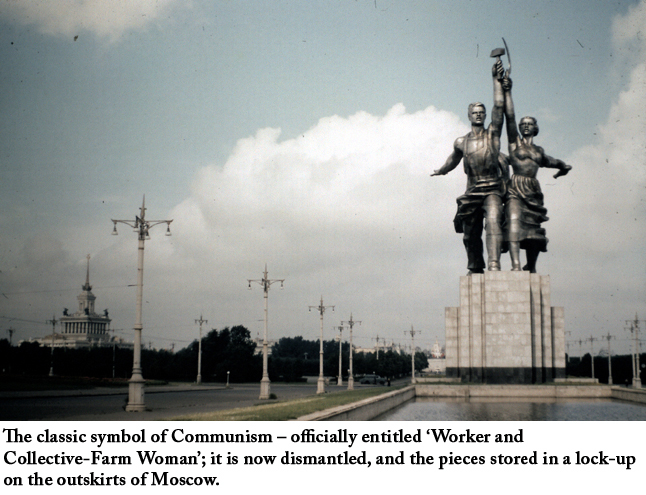

The material results of this high academic level were clearly translated into concrete terms in the so-called Exhibition of National Economic Achievement (вднх), not far from the camping site. A vast area had been set aside for experimental plant nurseries, pavilions of all the Republics, in which national produce was displayed, and pavilions of science, engineering and electronics. A colourful scene was marred only by the incessant blare of canned music from the ubiquitous loudspeakers. The exhibition was massive. Few of the goods on display were always available all over the Union, but one got an idea of the variety and extent of Soviet industry and agriculture.

For a young man life in Moscow was not at all dreary. Soviet young people were highly motivated and dedicated to the success of their country and, rightly or wrongly, their system. They enjoyed food and lots of drink, and they danced and sang as if the problems of the world hardly existed. They swam, played sport with gusto and enjoyed their many parks. A regular sight there, which signified the timelessness of a great country, was the chess area where old men with flowing white hair and beards matched their skills with young schoolboys. All this was way beyond politics and systems of government.

Tim was struck by how well prepared these students were in any political situation – how well drilled they were in familiar arguments. Perhaps, he felt, ‘I had the facts to argue in two or three but not six or seven’ cases as they did. It turned out that these students were Members of the Committee of Friendship.

At the Ministry of Higher Education Professor Bogomolov, head of the Pedagogical Institute, told us: ‘A professor earns 10% more than an engineer.’ ‘How much does an engineer earn?’ ‘Ten per cent less than a professor!’ It was typical of robust Russian humour.

The People’s Friendship University of Russia, founded in 1960 as the Patrice Lumumba Friendship University to provide higher education and professional training for third-world nations, was thought by Western intelligence agencies to be a training ground for KGB activities. Conversation threw up the usual rude remarks about NATO – nearly every Russian student or lecturer harped on about NATO being a threat to the Soviet Union. Nigel was wary of our contact, a somewhat sinister character with a Latvian name – Zhuravels. He felt distinctly uncomfortable in that building. On subsequent visits to the Soviet Union in the Central Asian republics Nigel would come across ‘graduates’ – actually drop-outs from the Lumumba University, who had been sent away to these far-flung outposts where perhaps the climate was less severe, but the racial discrimination intense.

Two of the most interesting types of young people in Moscow were the stilyagi or fartsovchiki (spivs) and the zolotaya molodyozh (gilded youth). The spivs were typical of their kind and the more professional of them offered anything from a good dinner to women to encourage a bargain. Their fascination with all things Western was plain to see: one young man introduced himself to Peter because he thought he looked like Marlon Brando and this fellow wanted to get to Hollywood. Western clothes at that time fetched exorbitant prices in an extensive black market. Peter talked to another who liked ‘money, clothes and girls’ and just would not believe that ‘I would refuse to sell my soul for a million roubles’. Talking his language, Peter said that if he wanted a million roubles he was smart enough to get them without having to sell his soul. The spiv and his companions liked that.

At the other end of the scale came the gilded or privileged youth whose parents held good positions making them members of Russia’s ‘new class’. There were many of them. The girlfriend of one, a minister’s son, explained: ‘Their antics will surpass even the revels of debutantes on a London tube-train.’ All Moscow streets had a VIP traffic lane in their middle. At the time of the famous May Day celebration, when Khrushchev and the government were busy taking their salute, when central Moscow streets were closed, the minister’s son, his girlfriend and some companions, were tearing around the VIP lane in the ministerial car, having a thoroughly mobile and alcoholic party.

Mehmed wanted to buy an icon. He had brought a small suitcase containing new cheap nylon shirts, socks and underwear for men, being told that one could exchange these for an icon. Traicho was in on this plan and introduced a new friend, Borya, who would bring an authentic icon (stolen from a church) and take the merchandise. The exchange would take place the next day. Mehmed was already getting nervous and having second thoughts about the whole thing. The next day in the middle of Red Square Borya quietly slipped into the Kombi through the rear door with the icon wrapped in a Herald Tribune. Mehmed was at the wheel with Traicho sitting next to him. Immediately after Borya got in, Traicho said ‘drive on’. Borya was giving the instructions. To Mehmed’s dislike they left central Moscow and drove to some obscure suburbs. It was getting dark. It then became clear that two police cars were following. After about three-quarters of an hour, with each trying to lose or overtake the other, the police cars won. Traicho said, ‘Don’t move. Stay in the Kombi and don’t say a word.’ He got out and produced his red Bulgarian passport together with his Communist Party membership card. Borya could not produce an identity card and was taken away. Mehmed and Traicho drove on. The icon stayed in the Kombi. Mehmed cursed himself. Traicho said, ‘Don’t worry. They won’t do anything to you. They are waiting for you to cross the line.’ He then explained his story about earlier visa manipulations. He had promised the Soviets that if they would give us the visas, Mehmed, son of a jailed Turkish ex-minister then on trial in Yassıada near Istanbul, would cross the line in Moscow and start working with the famous and dissident Turkish poet, Nazım Hikmet, who fled Turkey in 1952. This was going to be big news in the press both in Moscow but more so in Turkey. In the meantime, Mehmed was more worried about Borya on the one hand and what to do with the icon on the other. Later, before leaving Moscow, Mehmed learned from Traicho: ‘They are going to give a life sentence to Borya,’ he said, ‘and are very angry with you. But don’t worry. They will not do any harm to you.’ Mehmed would have reason to feel less sure about that on leaving the Soviet Union, some weeks later, at Julfa train station.

During the next two weeks two apparently related incidents happened, one after the other. First, Mehmed met a scholar of Turkish at the Foreign Languages Faculty in the University, an academician called Sergei Alexander Alexandrevich. He was a close friend of Hikmet, who at that time was in Castro’s Cuba giving lectures. Hikmet, said Alexandrevich, was inviting Mehmed to join him in the USSR and work with him as a young-blood Turkish Communist. Life would be very pleasant. Mehmed talked several evenings with Sergei in the restaurant of the Hotel National and told him this was not on.

Next came a meeting with Raya Alexandra Alexandrova at the Moscow circus. Mehmed was watching neither the circus nor Khrushchev, who happened to be in the audience, but the very attractive young woman sitting next to him – Raya. Her husband, an army officer, was out of Moscow. Mehmed saw Raya several evenings at her tiny flat. She went out of her way to explain how pleasant life in the Soviet system would be for a young Communist Turkish dissident.

Some members of the Expedition felt that Traicho had another agenda in Moscow. He often disappeared for a few hours, as he did the day before leaving Moscow. Years later – see the Epilogue – Nigel managed to decorticate bits of our colleague’s twisted path through life in a talk with Traicho’s granddaughter. There probably was an element of truth in Traicho’s visa story. Mehmed to this day is unsure of it but remains perplexed about the incoherent behaviour of different bits of the Russian bureaucracy towards him.

It was time to plan getting out of Russia – there had been no time to finalize this before leaving England. In retrospect it was surprising that the Expedition was allowed into the USSR in the first place.

Mehmed now suggested that ‘his’ Kombi should go by train from Tbilisi or by boat from Baku, while Tim and consorts would head through Romania and Bulgaria to Istanbul and then strike out eastwards. The two groups would thus not meet again until Iran. Traicho’s friends then came up with an introduction to the secretary of the Komsomol – and a channel for obtaining permission to drive out of Russia into Iran as well as visa manipulations, about which more would become clearer shortly. After days of bureaucratic fuss, including a premature celebration in vodka until the bottle ran dry, Traicho’s Iranian visa was refused, a trip to Leningrad was cancelled, and other hassles intervened. Finally, it was decided that Tim and crew would indeed take the Balkan route, while Mehmed, Nigel and Tony would head due south, the more direct route to Iran – but with what turned out to be interesting ‘excursions’ on the way. A German embassy engineer told Tim that the gearbox on Kombi Z1235 would get no worse – so carry on blissfully to Iran.

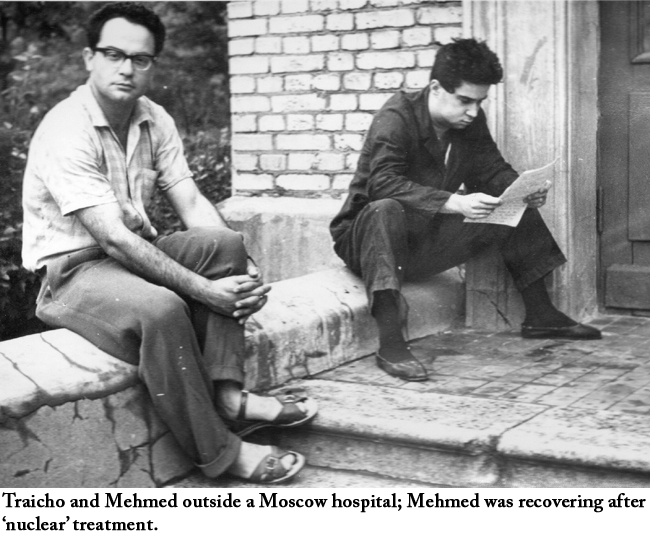

A new complication now erupted. Two weeks after the Borya incident, Mehmed’s right gland swelled up as big as an orange. He went into a coma and was taken to Gorky Hospital. The facilities were not impressive – nor the results. Yet this was the No. 2 City Hospital, considered suitable for treating foreigners. Despite misgivings, Mehmed received top-quality care in what the Gorky Hospital called in their medical jargon the ‘Nuclear Treatment’. Soon he had almost recovered. He would now fly to Sochi to meet up with Tony and Nigel who, in the meantime, with Intourist on their backs, had by now left Moscow to drive south in the second Kombi. The hospital gave Mehmed a free air ticket to Sochi.

Traicho, Tim, Roger and Peter came to wish Mehmed bon voyage. They were leaving for Istanbul via Kiev and Sofia. That was the last time Mehmed saw Traicho, who would leave the Expedition in Istanbul after, in all probability, deciding then that it was time to abscond to the West. And yet, as Bob recalls, during a subsequent last year in Cambridge, Traicho still seemed able to return from day trips to London equipped with bottles of slivova and pickled gherkins supplied, apparently, by the Bulgarian Embassy.

Shortly before leaving Moscow, the news percolated that a student friend had lost a holiday job due to being seen around Moscow with the ‘foreigners’. He had then found another job as interpreter to a foreign delegation at the dubious ‘World Youth Forum’ then happening in Moscow, only to leave that with some excuse as he rejected the odious task of having to make out reports on what the delegates said privately amongst themselves. He thus lost badly needed income to tide him over the academic year. He will pop up again soon in this tale.

The eve of departure from Moscow was a moment to reflect on experiences gained. Roger recalls impressions of Russian women: their old-fashioned clothes; their place in society. On the one hand, plenty of the younger female generation were going to university. On the other, women were employed on building sites, in road mending, painting white lines by hand, etc. Women were also bus and train drivers, before that was generally common in the UK. As Russians recalled again and again, these were scars inherited from the cull of their males during World War II. Women, as Nigel observed, did everything in the rearguard – and frequently at the front as well. The position of women would continue to improve in terms of careers and opportunities until perestroika, when their situation began to come under pressure from endemic Russian male chauvinism. Peter recalls how Western clothes at that time fetched exorbitant prices in an extensive black market. Some Expedition members supplemented meagre funds by selling Marks and Spencer pullovers literally on the streets. And they were snapped up by avid young Russians.

The most bizarre malcontent encountered was a middle-aged housewife who stormed up outside Moscow’s National Hotel, a favourite of Western journalists. Almost foaming at the mouth, she stood her ground for ten minutes while one of the Expedition’s Russian speakers was hastily extricated from the hotel barber’s shop. She was tired of the slum where she and her husband were living. She had been promised a new flat, but the promise had not been kept. She had seen or tried to see everyone from local Party Committees to President Brezhnev to no avail. That morning she had been told to ‘go to hell’ by a Moscow building organization and wanted to know whether ‘the Western Correspondents’ would come with her, take pictures of her flat and ‘put it in every newspaper in the West so they can see how we live’. It so happened that Expedition members had cards from the Sunday Times saying they were ‘accredited foreign correspondents’. The reactions of these ‘correspondents’ were guarded, as police traps were an occasional reality. But curiosity and the temptation got the better of them. The woman’s apartment block was very near central Moscow and was indeed a hovel of long, dark corridors, dirty ashbins outside each door and so on. No sooner had she opened the front door than a fast exit was needed. Her husband who ‘would kill me if he knew about you’ was calmly sleeping inside. If the incident had any value it was to prove that Moscow’s housing problem was not quite as solved as everyone would have had one believe, particularly as the woman concerned had done two years service as a tractor-driver on the Virgin lands and her husband was a Party Member.

Departure from Moscow was indeed long overdue; arrangements were finally completed with authorizations dragged out of the obstreperous Intourist. Nigel and Tony left in one Kombi for Kharkov and Tbilisi. Tim, Peter, Roger and Traicho headed for Kiev with the other Kombi. Mehmed was to catch up by plane. Bob was ‘lost’ somewhere in the Balkans. A first group would meet up in Istanbul. Everybody would reunite in Tabriz or Teheran.