4

HOW TO GET OUT OF RUSSIA

South-west by south from Moscow the road heads straight as a die through the great Russian plains to Orel (‘the Eagle’) into the Ukraine. Several lorries lay askew, broken down by the roadside, with their sweating drivers attempting major repairs – the engines being removed from their mountings, and being stripped and rebuilt by the roadside. Russian drivers were their own autonomous mechanics. One could not obtain a driving licence in Russia in those days without passing mechanical qualification tests.

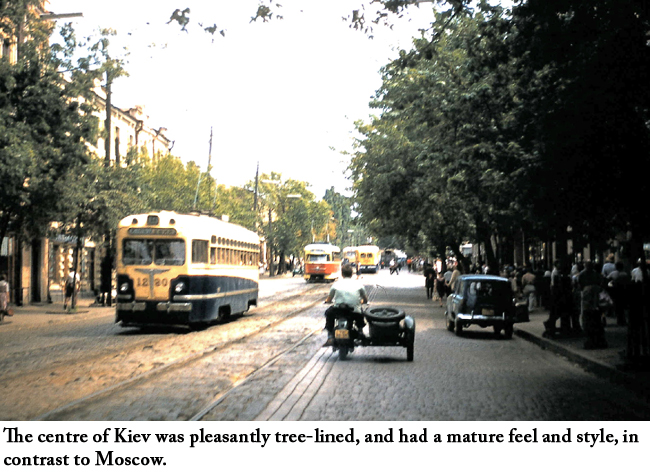

Further on to Kiev, the cradle of the Rus’ or Russian state, the wheat lands stretched to the horizon with the earth painted with patches of gaudy sunflowers. Farm machinery was replacing some horses. Houses were beginning to be quite trim after the drab blocks of Moscow. Kiev’s city centre was pleasantly tree-lined and had a mature feel and style, in contrast to Moscow. Intourist had issued vouchers for the Kiev campsite. For some reason – probably Traicho’s desire to negotiate everything – yet another debate was to break out with these friends of the tourist on the method and amount of payment. Already when leaving the Moscow campsite, for no good reason an argument about payment had flared up. There was a definite feeling of being told to move on and out.

The following day Traicho disappeared again for three hours. He had fixed an interview with the pro-rector of the Kiev Polytechnic Institute. A bright and friendly student called Viktor turned up to volunteer a quick tour of Kiev with non-stop commentary. Next on the agenda was a trip further up the Dnieper River to one of the youth camps that nearly all students go to for some part of their summer vacation. Viktor, and another student, Lyudmila, rode escort. At the camp everyone was allotted palotki (tented accommodation) before a Butlins holiday camp-type dinner, followed by dancing on a rickety wooden floor to tinny music until late, and by the light of a large harvest moon.

Peter judged later that the two days spent at the holiday camp of the Kiev Polytechnic Institute provided the best opportunity throughout the stay in the Soviet Union of getting a feel for the character of Russian students. No official guides were involved – simply an invitation from an ex-student of the Institute. The camp had a splendid location on the banks of the river. It had been built and run by the students themselves who thus got three weeks’ free holiday each summer, a regular practice in the USSR. The greatest hospitality was showered on these unofficial foreign guests – perhaps because they were ‘unofficial’. Talk went on throughout the day and long into the evening with the many of them who spoke English and they involved the visitors in their activities, including a trip down the river and an occasion for Tim to show his rowing skills. For an annual holiday these students followed a strict programme each week-day: up at 7 am; breakfast; meeting for the purpose of administration or official discussion; a morning’s work on neighbouring collective farms; lunch; two hours’ rest; sports training; dinner; free time till lights out at a rigid 12 midnight. During their few free hours there was nearly always something arranged such as a concert or a dance. They seemed to thrive on this organized existence, all the items being compulsory except for sports training which everyone did anyway. Some American schoolboys, who were official guests, had had quite enough after ten days. Tim, Peter, Roger and Traicho were relieved that the full day they spent there was Sunday, the ‘day off’, although activities still went on non-stop. These students were happy and active, nothing apathetic about them. But the camp provided little challenge to foreign 23-year-olds.

Roger, and an American friend, Dolores, met en route, wandered off to take photos in the old district of Kiev known as Podol. All went well for a while, until they noticed that there was one particular Russian citizen who popped up now and again saying, ‘you can’t take photos’. Roger and Dolores took no notice except to point the cameras up in the direction of the sky and pretend to take pictures of churches merely as a precaution. There was nothing apparently forbidden to take anyway. Just as they were meandering through the market place one miserable, dirty, scruffy, unshaven policeman came up and told them, by various gesticulations, to go along with him to the nearest police station as ‘they’ did not like ‘them’ taking photos. They were kept waiting for an hour in a grubby room, then a copper told Roger to open his cameras and expose the film. Roger refused and they were incapable of opening the cameras themselves. All the conversation was in their respective languages, neither party really understanding the other. Repeated demands for representatives from Intourist and respective embassies made the police so fed up with the sight and sound of the determined photographers that they finally let them go, with no more than a vague sort of promise not to come to that area again. Doggedness had paid off.

In a restaurant later that evening, by remarkable chance, up popped Vladimir, a 20-year-old engineering student with whom Peter had briefly talked outside the Moscow Film Festival. He was a typical eager young Russian, and insisted on organizing an animated evening at the Kiev flat of his grandparents. The grandparents were poor, and Vladimir himself spent every kopek he had, not only to entertain his guests, but to give each of them a little present. The flat was poor, but immaculately clean and comfortable. On the wall of his bedroom, converted into a dining room, stood an icon, put there at the express wish of his grandmother, an ardent Christian, ‘because English people like the God’. The religious trends of Russia were illustrated perfectly within the family when his aunt joined us, a middle-aged widow who had lost her husband and only love in the war and now lectured for a meagre salary in history, politics and economics. The grandmother was the devout Christian, the aunt somewhere between Christian and agnostic, and he, Vladimir, the complete atheist.

He was no leader of youth, just an ordinary young man, and in his good English rapidly proceeded to sing nearly every known English ‘pop’ song. He was desperately keen on jazz and asked to be sent English books. So here he was, a Russian, like millions of others. What did he think of the system that governed this country? Each time the conversation swung in that direction he was immediately guarded, if not fearful, and stuck to the party line.

On leaving Kiev the next day, Vladimir came to the outskirts of the city to say farewell. In that final conversation, out came the truth. He expressed dissatisfaction with the leadership, a yearning to be free and a desire for knowledge of the West. Yet, trapped by the system, he said, ‘Peter, I have no choice but to be a good Communist because it is by that means that I shall eventually be free!’ In other words, it was inevitable that Communism would slowly change as the country advanced and its standards improved, and he had little choice but to go along with it. For poor Vladimir, however, with whom Peter kept in contact over the years, it would not be at all easy. Peter learnt some 30 years later, when able at last to see him again, that he was picked up by the KGB as soon as the Kombi disappeared down the road to Romania. The fact that he was the son of a Red Army Colonel eventually saved him, but not before questioning, putting a book that we had given him down the lavatory and other unpleasantness. Because of his languages, he was later invited to join the KGB, but told that he would have to report all private conversations with, and about, foreigners on delegations. Vladimir refused and was then told that, if he did not join them, they would not support him for any job he went for in later life, i.e. he would go on the black list. He ended up working with his wife on Sakhalin Island, near Japan, to scratch a decent wage. An engineer, he was later sent into the Chernobyl site after the disaster to help clear up, but without sufficient protective clothing. Many of his colleagues have died since, and his own health was seriously affected. He now lives in Kiev on a small pension, his talents wasted. ‘How lucky,’ thought Peter, ‘we have been to be born where we were.’

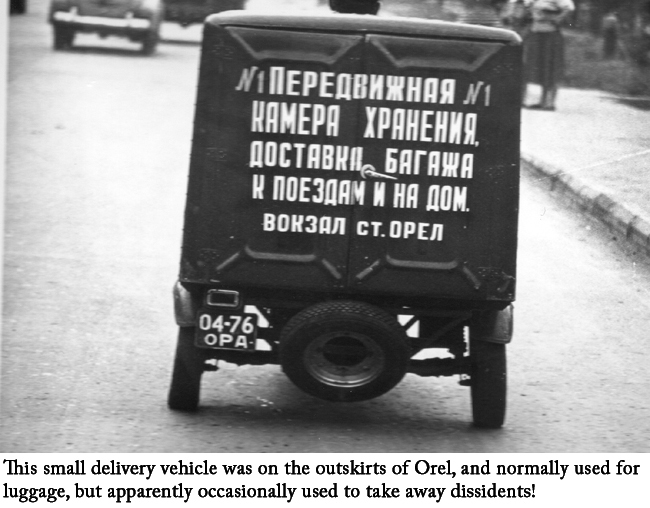

The Kombi ‘got lost’ in the early hours of the morning. Shortly, a fine water mill, which was working round the clock, hove into sight. Asked where we were, the miller did not seem to have any clear idea. Such men and places are untouched by change until the time comes when they are either superseded or abolished. Not until five o’clock in the morning did the campsite in Chernovtsy emerge through the early light. Later that morning, a policeman arrived at the tent, enquiring, very pedantically, ‘Where were you, last night?’ There had been an accident, said he, on a certain stretch of road. It all smelt as if the police really wanted to know what the occupants of the Kombi might have seen. It later turned out that the road had passed close to a military site. Traicho himself was thoroughly interrogated. Finally these people relaxed their clutches, opening the road to the Russian/Romanian border. Getting across was a lengthy business, on a hot and sultry day. The only real difficulty was when Tim fished out of his pocket a £1 note that he had not declared on entering Russia. He lost it. At least the Romanian border functionaries had had something to do that day – they packed up shop once formalities were complete.

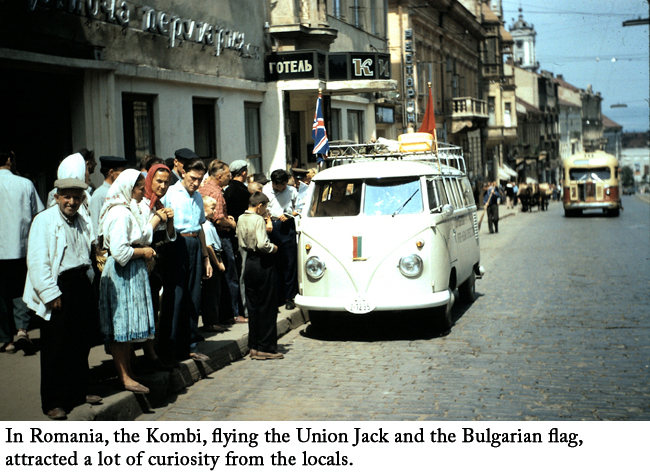

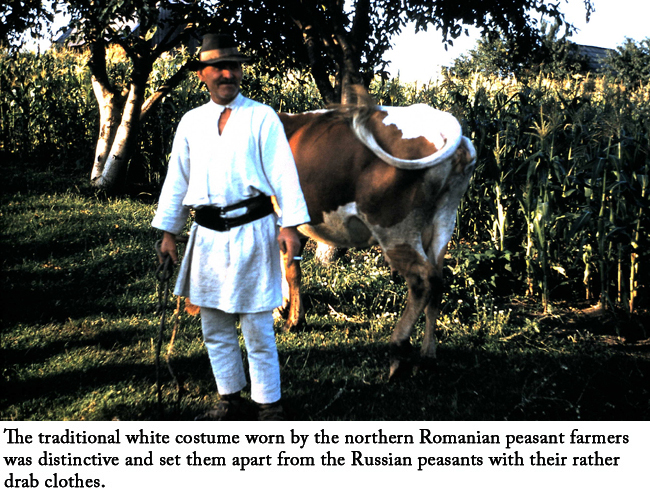

Once in Romania, the Kombi, flying the Union Jack and the Bulgarian flag, attracted a lot of curiosity from the locals. The traditional white costume worn by the northern Romanian peasant-farmers was quite distinctive and set them apart from the Russian peasants with their rather drab clothes. In Bucharest, after much hassle, one of the best hotels came up with a couple of rooms. Nowhere else was available to stay with official vouchers. Over dinner a dissatisfied Romanian doctor struck up conversation. He introduced some alarming if unlikely figures. He claimed there were 2 million political prisoners; that 30 out of his year in medical school were in jail for demonstrating against the invasion of Hungary (for which Romania had sent troops); he would have to work for a year as a doctor without eating in order to be able to buy a car. Perhaps with the benefit of hindsight his lamentation deserved more notice. And Ceausescu was not even in power yet.

Dusk fell on the rough road to the Romanian/Bulgarian border. Peter nearly mowed down one of the numerous and unlit carts drawn by oxen or bullocks. In the last town before the border it was too late to change any remaining cash. There was nothing for it but to blow the lot on local konyak and wine generously offered in a border boutique for purchase at inflated prices. It then emerged that everyone had differing points of entry marked in their visas for Bulgaria. Traicho again performed and soon fixed that little problem with the officials. Camp was set up by the roadside shortly beyond the frontier.

Over rolling hills some atrocious and some good roads led ultimately to Sofia, where Traicho squeezed everyone into the Hotel Grand. It lived up to its name. Traicho was host for the brief stay in Bulgaria. Too much slivova in too large glasses was washed down with dinner. The party just about managed to stagger to bed. A short tour the next day revealed a city that was not as beautiful as expected. Traicho, funnily enough, did not seem to know the more historical places of interest at all. The centre of Sofia was curiously soulless in the manner of Bucharest. Worse still, an important member of the government had just died and all day long small and large processions trouped past for all the world like so many sheep.

At last it was time to head down the road on the last stretch to Istanbul. Dinner en route was eaten expensively and in style in Plovdiv in a restaurant recommended by Traicho – the biggest and best in the area. ‘Some Communist state!’ muttered Tim. It also seemed, with the benefit of hindsight, that Traicho was happily offloading some spare cash before making a definitive exit from his native land. The Kombi swept through the Bulgarian side of the border in about five minutes, helped by some sweet-talking of the official by Dolores, our American passenger, who had been with us since her photo episode with Roger in Kiev. Peter, meanwhile, was following behind separately with her companion, Howard, in a Volvo. They came within inches of their lives when the Volvo’s back axle collapsed sending them spinning all over the road.

The Turkish side of the border was reached at 2 am. Four hours later customs were cleared – not bad given that this particular Kombi had no carnet and its papers were in Mehmed’s name. Everyone huddled by the roadside until the sun became too hot.

The Thracian countryside here was completely different from back across the border. It was arid, dotted with the poplars that Turks lovingly plant for baby sons so as to provide timber to build their houses when they mature and marry. Such grass as grew was yellowing and sparse. A first taste of genuine Turkish coffee was served in a kerb-side café in Edirne. Turkish military were very noticeable and abundant about this sensitive big city on the marches of Greece and Bulgaria. The shadow of the recent Turkish army coup lay long.

Arriving in Istanbul in late afternoon, the first call was at the house of Ridvan Mentes – an old family friend of Mehmed. Mehmed’s co-expeditionaries had been expected two days earlier so no one was at home. A policeman offered to show the way to Mr Mentes’ office. The poste restante arrangement, previously set up in Istanbul, revealed that Tony and Bob had both arrived, but they were nowhere to be found. An army cadet helped find a room for three in a small hotel.

It was a first taste of Istanbul. Part of the city, particularly on the Pera side, was markedly Western, with streets winding down to the Golden Horn waterfront, dating from Genoese and then Ottoman days. All around was an abundance of private enterprise, a refreshing change from the Soviet bloc. Hamal porters bore huge sacks of merchandise on their powerful backs; reputedly the strongest of them could carry a piano. From the Galata Bridge men coaxed fishing lines for supper. And everywhere was the bustle and liveliness of a thriving port at the foot of two continents.