7

A BIT TOO FAR EAST

Meanwhile, 1,250 miles away as the crow flies, still in the Soviet Union, Mehmed and Nigel were seeing life their way.

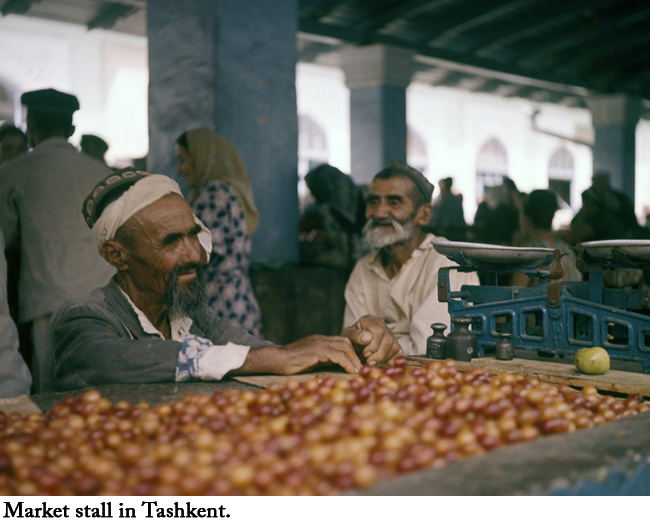

Tbilisi was the southernmost and cheapest jumping off-place for Tashkent in Central Asia. The expense was prohibitive, but having got there the cost, for once, could be considered last. A TU-104 aircraft rocketed Mehmed and Nigel through the night to Tashkent where they arrived before dawn. Here was at once a different world, but one becoming half-familiar. Russian architecture still disfigured what might once have been one of the most fascinating cities in the world. But Tashkent – the ‘stone city’ in Turkic – remained a place full of surprises.

In a restaurant for breakfast that morning, in a long, thin room with a narrow carpet down the middle, Mehmed and Nigel shared a table with a one-eyed writer called Ignatyev (an exile?) and his ethnic Korean companion (minder?). On discovering that these were foreigners, Ignatyev ordered what he called portveyn (a lethal concoction of red wine and probably methyl alcohol). As this concoction went down, his companion became more and more agitated as Ignatyev grew more and more vociferous and before long they were chucked out of the restaurant. Nor could Mehmed and Nigel stay – they had to meet their mandatory Intourist guide later – but how after such a breakfast does one walk straight down a restaurant on a very narrow carpet?

The Intourist guide was not your regular sort – he spoke fluent Turkish and knew more about English football teams than Nigel did. He was actually a Ukrainian. Being driven around Tashkent gave our travellers an opportunity gradually to sober up. In those days, Tashkent was typical of the old Russian colonial era with a ‘European’ and a ‘native’ quarter. Once the tour was officially over, the guide was persuaded to leave Mehmed and Nigel on their own. Thankfully there was a chaikhane in the ethnic quarter close by and severe dehydration was corrected with copious cups of tea.

A young Uzbek at the next table noticed the medallion hanging from a chain around Mehmed’s neck, and could actually read it. After some time in conversation, in Turkish, Russian, Uzbek and English, Kazym, for that was his name, invited Mehmed and Nigel to his house. This was a first introduction to a proper Central Asian family with all the formalities which apply and also very interesting company. The next day came a new invitation from the family to an ‘Uzbek Pilau’, a dish specially prepared in honour of guests. On returning to the hotel that evening, however, the guide was waiting. Kazym was grilled about why he was with these strangers, etc. On a subsequent visit to Tashkent, Nigel found the family again and discovered that this event had had consequences. Kazym’s elder brother lost his job, and the whole family were in difficult circumstances.

One cannot live indefinitely in a place at the rate of one pound sterling an hour, so the next night Mehmed and Nigel flew to Baku. Baku was a closed city. How they were able to go there in the first place is a bit of mystery. They were followed most of the time, sometimes more obviously than others. Capital of the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR) – another Turkic province – Baku was big and bourgeois, floating on oil. Economically the town was far ahead of the rest of the Republic. It claimed to have the best petro-chemical institute in the world and also had many other top-level higher educational establishments. Unlike the Georgians, the Azerbaijanis were more willing to travel to other parts of the Soviet Union, and many surplus graduates were sent to Kazakhstan and Kirghizia. An atmosphere of boom pervaded the oil-laden air. The town was also situated in a strategic zone. A special permit was required for photography. During lunch Mehmed and Nigel were closely observed by a rather unpleasant-looking couple and found, on return to the hotel, that Mehmed’s camera had been opened, and all the film which the intruders could find had been exposed.

The old quarter of Baku had its charms and was apparently a popular filming location. At the entrance of some old buildings there were still the sculpted medallions proclaiming the identity of early British insurance companies which had exploited the presence of oil and the wealth it created. At a jazz concert in Baku the most popular piece was The American Patrol. Chatting with a young man playing backgammon outside his house, Mehmed found that Azeri and Turkish are extremely similar. This led to an invitation to go to the beach, a few miles out of town, the following day. On arriving at the rendezvous, Aga Selim, the young man, showed up with a book under his arm and the excuse that he had to study for an urgent assignment so could not take them to the beach. It was worth trying to go out of town anyway and eventually a taxi drove Mehmed and Nigel north across a sandy plain covered with oil rigs. ‘Where do you come from?’ asked the taxi driver. ‘East Germany,’ said Mehmed, on the basis of his excellent German; ‘Czechoslovakia,’ said Nigel (apparently referring to his alleged accent in Russian). ‘Oh yes, I was in hospital in Prague for some months,’ said the driver. Abrupt end of conversation. The silence was broken when a policeman jumped out from behind a bush, yanked the door open and said (in Russian), ‘Who have you got in there, idiot?’ ‘One East German and one Czechoslovak,’ came the reply. ‘That’s what you think – turn around and go back to the hotel.’ With the policeman in the car, there began a seemingly interminable argument about who was going to pay for the return trip. Unaware that Mehmed and Nigel could understand him, the policeman told the taxi driver all the details as they rode back. ‘The signal went out from Headquarters,’ he said, ‘to stop this car wherever it might be.’ He was so excited. Mehmed hoped he got promoted.

Soon it became impossible to do anything. A row with the Komsomol resulted in such pressure being exerted that it was a pleasure to leave, as it was indeed, one suspected, what they hoped. With mixed relief Mehmed and Nigel caught the night train to Tbilisi on 6 August.

Tony had already gone to Istanbul with the Kombi. Mehmed and Nigel were left in Tbilisi on their own for a few days, before catching the train to Julfa and the border. They visited the mosque (under surveillance), while Mehmed got into conversation with other Turkish speakers in the bazaars, who were less than polite about their treatment at the hands of the Georgians.

Nigel found buying train tickets to Julfa quite eventful. The only currency he had left was in black market roubles – and, moreover, in large denominations of 100 roubles, an infrequent sight. On trying to pay with one of these notes, the woman in charge went downstairs and walked up and down chanting, ‘Who’s got change for a hundred rouble note ...?’ The local Intourist manager, called Edermann, caught Nigel’s eye; it was clear he knew or guessed where that banknote came from, but said nothing. (A year or two later, Nigel was in Tbilisi with a small tour group and it was also clear that Edermann had not forgotten.)

The charm of Tbilisi restored spirits and a few more days were spent dodging the escorts – to the intense amusement of the spectators – watching football matches, and thoroughly enjoying life. Attempts to study the educational establishments of Georgia failed after relations with the Komsomol broke down. There was no way of hanging on any longer in Tbilisi – visas had already been extended twice. A farewell supper, with Intourist minder Tengiz and his stunning girlfriend from Leningrad, gave Nigel food poisoning, which made the impending train journey a little difficult.

So began the two-day-long train journey, in a very comfortable compartment. Down the line to Yerevan, Nakhchivan, along the Turkish border, past Mount Ararat and then into Julfa, the border town with Iran. Nigel slept most of the time. Mehmed talked to curious renegades, quasi-dissidents, who were holed up in the restaurant car.

As a parting shot, the Soviet customs were particularly attentive. After seven weeks in the Soviet Union, they must have felt that it was no less than their duty. Personal papers, diaries, postcards, any scrap of paper were carefully scrutinized. Addresses were confiscated. Nigel had to translate handwritten notes, diary entries and scurrilous poetry dictated to Mehmed in the restaurant car. Worst of all, they discovered the last of the dollars (fortunately no roubles) for which, of course, there was no currency receipt. Forty dollars confiscated – ‘You can have it back if you come within the next three years,’ they said. ‘Thanks,’ murmured Mehmed and sighed with relief as the train rolled slowly over the bridge into Iran.

*

Thinking back to that time, as Julfa receded down the railway line, provokes thoughts as to how Russia is evidence that governance may change while underneath the people remain the same. The massive rape of state assets under Yeltsin yielded to the new state thuggery under Putin. The Cold War has given way to a more subtle regime of East–West mistrust. Russian pride and Slav emotions smart at being perceived, so they think, as some sort of Third World country. Mindful of its former power and glory, Russia wants to be respected in its own backyard or traditional spheres of influence. In the last analysis, in place of fear, ‘Europe should realise how much it has to gain from a sound relationship with what is a very remarkable country’, as Peter Temple-Morris learned over his years as a parliamentarian with active links to Russia. He hosted the celebrated visit to the United Kingdom of Mikhail Gorbachev in December 1984. Soviet Russia in 1961 was a ruthless dictatorship, with dreary Communism and all the rest of it. But the warmth of the Russian people shone through.

*

It was an abrupt shift to the amazing atmosphere of Julfa on the Iranian side. Music, a sense of freedom, and normality. It was then that the news broke that the Berlin wall had just been built. Once together again, Expedition members in their conversation instinctively turned to the subject; a new barrier, physical and psychological, and above all brutal, had sprung up across the Europe that in both their travel and imagination they had sought to cross.