10

TURKISH CONNECTIONS

Eastwards from the Caspian lies the Turkmen Sahra spilling over into Soviet Turkmenistan. Half a million Turkmen lived in the Iranian part of the old Turkistan when it was divided between Iran, Russia, China and Afghanistan. With their telfeke Turkmen hats made from karakul, the Turkmen had always fascinated Mehmed: they are racially most akin to the Turks of Turkey and speak more or less the same language. They were thought hostile towards foreigners. A while before, some tourists wandering in Turkmen lands were mysteriously lost for good. Well-wishers back home advised Mehmed against going there.

Armed with letters of introduction – Iranians prized them – Kombi Z1235, with Mehmed, Nigel and Tony aboard, left Teheran for the Turkmen Sahra, and ultimately to Meshed and Afghanistan. After the Elburz Mountains the road dropped dizzily to sea level before heading to Gorgan, the door to the Turkmen Sahra and its main town. The land was green and fertile, studded with palm trees, smiling peasants, among the richest in the country. There was enough to eat, and work for all. Not all of Iran could boast such wealth.

A beautiful, clear morning shone on Bandar Shah where the Turkmen tribes start. It was a military zone, calling for redoubled prudence – not always the Expedition’s greatest strength. At midday, in scorching heat, the place was almost deserted. It was siesta time.

The first letter of introduction was to Murad Shomali, a young, energetic businessman who owned much of Bandar Shah’s industry which he had built almost single-handedly after the war using British, German and American equipment. His friend, a Mr Iranpour, had at one time been a member of the Iranian Communist Tudeh party and suffered five years in jail for his sympathies. He was still the political big shot for the area as the elected member to the Majlis – the Iranian parliament.

The Expedition members’ ‘circulation cards’, were now a month out of date. Where should they be renewed – in Teheran? ‘What the hell can I do?’ Iranpour asked, frowning, when Murad Shomali suggested he take these ‘illegals’ to Gorgan to get new cards. Then discreetly in Persian, Shomali told Iranpour that Mehmed was Turkish. … Before long everyone was bowling down the road to Gorgan, Mehmed at the wheel, Iranpour beside him, already old friends. During an obligatory stop at a police station the chief said everyone should have checked out of the police station in Bandar Shah. This was a frontier zone with the Soviet Union and checks were pernickety. A fugitive who had just crossed the border that night was huddled under the stairs. Nigel started negotiations in French and got nowhere. Iranpour just sat still. Then Nigel had a brainwave and in ‘his best’ Turkish asked – ‘Do you speak Turkish?’ ‘Evet, efendim,’ said the chief enthusiastically and Nigel promptly passed the buck to Mehmed. Now with Mehmed in the driving seat (metaphorically and physically) everything got straightened out. A Turkish colleague up in the frontier area had once given the chief a very good dinner. New cards were issued at once.

Gorgan was the centre of this fertile farming area. Modern agricultural methods were boosting its importance and wealth. Iranpour, a movie fanatic, suggested seeing Perfect Furlough at a new cinema. This was followed by kebab washed down with beer and vodka. Talk over the table ranged eclectically from such things as the Turkmen marriage system, their 95 per cent illiteracy rate, how there were 300,000 of them but their numbers were static due to tuberculosis, how they kept to themselves, how the elders were the ‘police force’, and how they had no doctors or hospitals for the whole area – ‘people just die!’ They were a proud, tough, strong race of fine-looking people – but you could get killed just for looking at their womenfolk.

Iranpour had a new idea. The next day was the bazaar in Akkale. Why not go there this evening and stay with Mehmed Dürdü (yet another letter of introduction)? They arrived in the darkness in front of Mehmed Dürdü’s house at about 10.30. The small town of Akkale slept soundly. Iranpour rang the bell. To someone upstairs who asked what the hell he wanted at this time of night, he said importantly, ‘Tell Dürdü Iranpour has come.’ Iranpour had indeed come, bringing with him three foreigners, one of them a Turk from Istanbul. Mehmed Dürdü, a short man of about 40, opened the door, wiping the sleep from his eyes.

Dürdü looked well off, judging from the collection of beautiful, dark red Turkmen carpets that adorned his house. Respectfully leaving shoes at the door, everyone sat down to tea in the true Central Asian manner, despite the hour. The cups were made in Japan, with no handles. There was no sugar. You sucked sweets while downing pots of tea, black or green. Morad Shomali had seen almost every capital of Europe and its nightclubs. Iranpour had seen Teheran many times. Mehmed Dürdü was a local Turkmen grown rich with his small cotton trade. These unexpected guests clearly amused him. He could understand Mehmed’s Turkish, or newly acquired Türkmence, but insisted on talking via Iranpour, and referred to Mehmed, Nigel and Tony as bunlar (these).

Dürdü originated from Uzbekistan. He had trudged over the high Pamirs away from Soviet oppression. He had walked for over a year. He proudly showed a full-length fur and sheepskin coat which the Kyrgyz wear as protection from the bitter cold. The samovar bubbled as everyone sat round talking. The women floated around in the background. The girls were really beautiful – as the sly and furtive glances of the young Cambridge-men betrayed. These women had clear Mongol features. Turks, Turkmen, Mongols, etc. all originate from the same Central Asian stock. The host had a wonderfully expressive face, a slight beard, a bald head and an amazing wit. The local schoolteacher came in and joined the cross-legged throng talking till well after midnight. Could ‘these men’, asked Dürdü, sleep on the floor? He then made the most comfortable beds the guests had slept in for a long time. They slept like sultans, covered by thick quilts to keep out the early morning chill.

The next morning there was the richest breakfast to be had anywhere in the world. There was butter (a rarity since leaving Cambridge), jam, eggs, fresh bread, pots of tea and, finally, about one pound of the best caviar in the world.

The dusty, uneven streets around the bazaar were already crowded. Turkmen men wore a papak or cap. They had come, each from his nearby oba, or summer village, bringing carpets to sell and to buy food for the week ahead. They rode in on horseback, tall, stately men, some with straggling beards, proud, in rich clothes, with their black or grey telfek or papak headgear. Their even prouder women, in rich red, also rode in on horseback. The odd horse misbehaved and jumped; the young Turkmen controlled them with masterly, nonchalant efficiency.

Tractors, lorries and carts jostled for position along the street. Herds of bleating sheep and goats waited to be sold. Clusters of chickens lay tied up on the sidewalk awaiting bidders. The women and children wore fantastically colourful robes with reds, yellows, mauves and blacks predominating. A large pushing and shoving crowd of people offered their various wares: carpets, rugs, hats, chickens, fruit, etc.

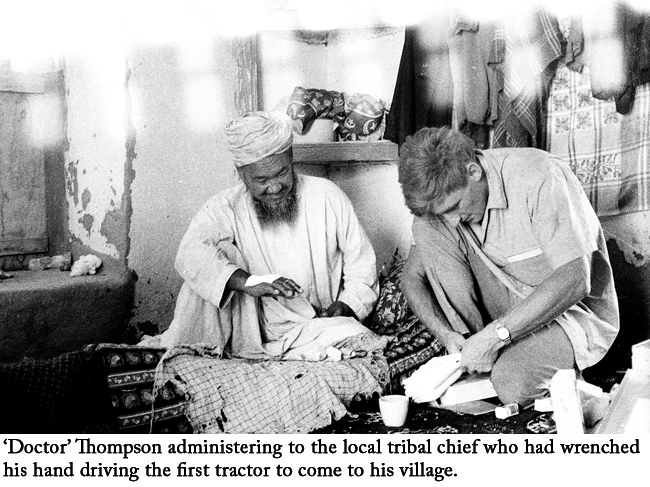

From Akkale the road ran north through the desert. The Elburz mountains rose through the bluish haze to the south. Alexander had marched along this road with his armies. The emptiness was broken by the occasional small oba with its typical Turkmen tents, noted by a former traveller as the ‘most ingenious ever designed, cool in the summer and warm in winter’. Refreshment at a Tomach tribal village, squatting on the floor of the headman’s hut, was pure yoghurt made from camel’s milk. Water is scarce in an oba. ‘Doctor’ Thompson administered to the headman’s swollen hand – he had wrenched a joint overturning on his new tractor. This was much appreciated. These were real nomads. They had no problem about their women being photographed at work making carpets. Two women took a month to make one 3 feet x 5 feet carpet.

Education had brought big social change to the lives of the Iranian Turkmen. Reza Shah had brought it to these lands 30 years before, although with brutality. Once completely tribal, many people now lived in towns with their primary and even secondary schools. Fewer now came out to the plains with their animals in the summer. Even girls were educated to prove that the Turkmen, like his brother, the Turk, could become quite secular and even reformative about religious matters. Mehmed had been to several Muslim countries, but only with the Turkic people did he sense the existence of a pondered balance between religion and a more secular appreciation of society’s priorities. Here he could feel relaxed about the atheism that was at the core of his philosophy of life.

In Gomishan chai was drunk in the local headman’s cloth shop, followed by an invitation to lunch at his house. The house was built vaguely in the Swiss chalet style, with wooden verandas going two-thirds of the way round its girth. The tin roofs drained the scarce rain off into storage tanks. That was the only water supply; ever deeper wells only brought up salt water owing to the closeness of the Caspian Sea. Many people owned no water supply of their own and bought it. No wonder they rarely washed! Their sanitary conditions were primitive in the extreme; they just defecated on the ground, so collecting hundreds of flies, which in their turn carried the dirt and germs and deposited them on the food and the people themselves.

While everyone reclined barefoot after lunch on cushions spread out on a superb Turkmen carpet, the local frontier-guard officer turned up with his notebook. Foreigners being here at all, it seemed, was a privilege. This was a military zone, normally forbidden to anyone but local inhabitants. These were the first Europeans seen here for a long time and they were a natural object of curiosity. The proximity to the Soviet border was intriguing. One small boy, in one of the groups of boys who sprung as if from nowhere to surround the Kombi wherever it went, proudly announced in Russian – ‘Yuri Gagarin is a Soviet sailor!’

After rice and sturgeon, fried eggs and camel’s milk, Iranpour talked about the problems of the area – especially insufficient educational facilities. Decades earlier, Reza Shah had killed many recalcitrant Turkmen while introducing education. Now the Turkmen thought they deserved more. They wanted to send more students to Turkey, to Germany, but passports were hard to get. Doctors were very scarce and this, together with lack of hygiene and water, accounted for the high death rate. Tony, as Expedition ‘medic’, noted that Gomishan, with a population of 8,000, had only two semi-doctors who were about his standard.

In Bandar Shah the security police gave permission to cross the military zone to an island for a swim. It was nearing sunset, with the sun’s dying rays a burning red, flashing across the still waters. The deliciously warm water washed away the dust of the day’s driving. A visit to the caviar factory followed. The next morning the best caviar in the world would make for a sublime breakfast. One pound cost £4. Mehmed, Nigel, Tony and Iranpour got through at least one pound between them.

After dinner Iranpour coaxed everyone to go to his beloved cinema again. This time it was The Fall of Rome with Sophia Loren. The cinema had a sheet, patched in many places, for a screen. The audience became part of the film itself, clapping, shouting, and screaming gently when excited. The night was spent at the house of Mr Sheri, the first Turkmen representative in the Iranian parliament – when it sat.

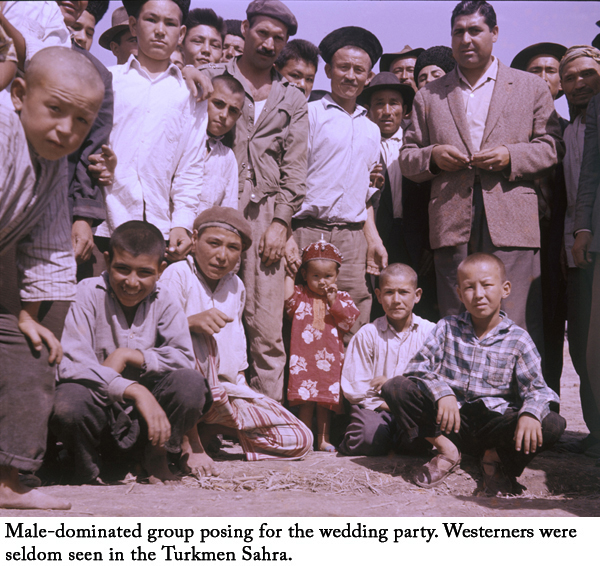

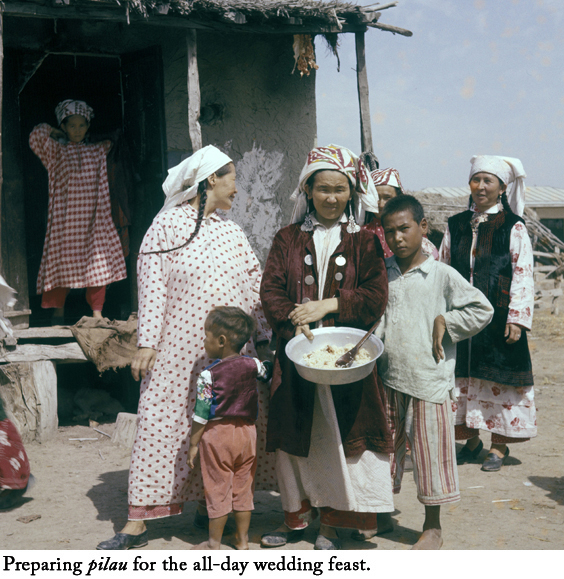

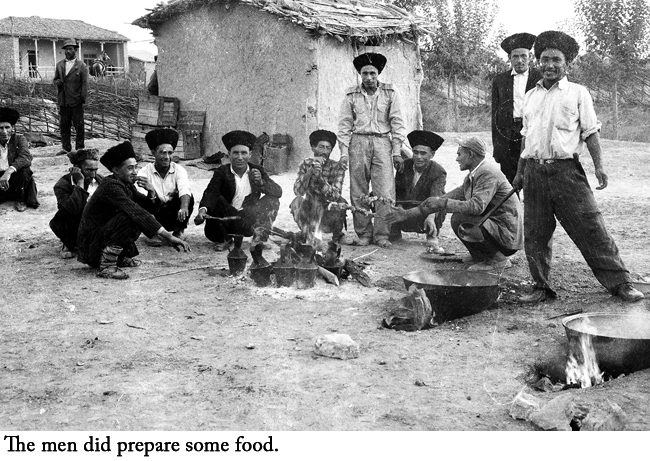

Next morning a motley, gloriously colourful crowd milled round a Kazakh house for a tribal wedding. The women were in their finery – the bride’s family womenfolk wore a white turban hanging down at the back of the head, and other regalia. There was positive encouragement to take the women’s photos, followed by an invitation to the bride’s house for chai with all the men. The men sat in one room, ranged around the four walls, the women in another – drinking their chai and eating bonbons. Suddenly the bride was approaching, so everyone hurriedly put their shoes on and dashed outside. Small ‘bridesmaids’ held banners. Close behind them came the older women, with the bride firmly settled in their midst, her head and whole body covered by a long, white shawl. Only the bride wore the ‘chador’. The other women left their fine faces uncovered. The bride disappeared into her house and large cauldrons of rice and meat were given a few more stirs ready for the big feast.

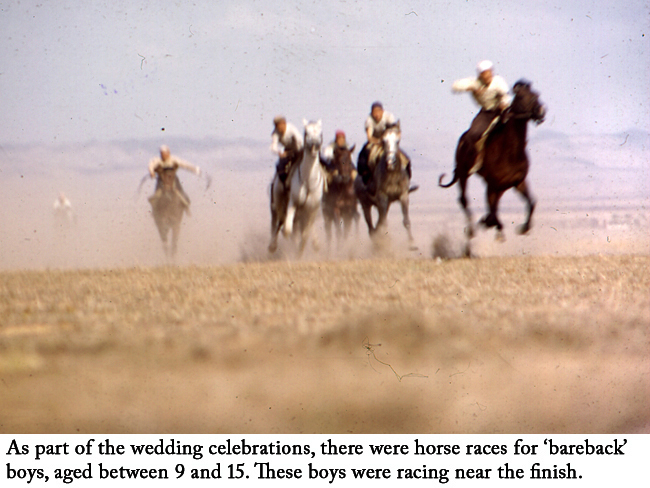

Now came a customary throwing away of money. The bride’s family threw away about 1,000 tomans (some £50) into the assembled crowd of friends, neighbours, beggars and children. They threw not only actual money, but also shoes, bits of tin, etc. The agile retriever got a toman. As part of the wedding celebrations, there were horse races for ‘bareback’ boy riders, aged between 9 and 15. The celebrations went on all day and in the evening music blared out.

About 2,000 Kazakhs lived in Bandar Shah. They had fled from the Central Asian steppes of Soviet Kazakhstan in 1934 because, as comparatively rich people, their belongings were forcibly taken from them by the Russians in their anti-kulak drive. Kazakh men were taller and thinner than the Turkmen, usually with impressive moustaches. Their language, Kazakh, belongs to a different Turkic group. They had come far from Uzbekistan to settle on the last piece of Turkic land to the west.

It was time to move on. After a superb lunch of rice with tender meat and salad, which the Turkmen call Istanbul Pilavi, Iranpour bade farewell. The Expedition had yet another letter of introduction to a Mr Nejjari. This was to be the start of a hilarious wild-goose-chase around the Turkmen Sahra.

Behind Mr Nejjari’s front door his young servant was obstinate, and his wife was having none of these strange men crossing the threshold without her husband’s permission. A student who was cycling by came to the rescue and an ‘acquaintance’ of his kindly let the party sleep in his new house. Erhan, 23 years old, still in the local high school, was already married; he had paid the princely sum of 10,000 tomans (£500) to the bride’s father for the privilege.

Erhan tagged along next morning as guide and interpreter in the search for Mr Nejjari and everyone headed further into the desert, along rough, bumpy cart tracks. The Kombi was on test to prove its versatility. It was extremely hot. Only later did it become evident that the engine had been driven too hot, thereby melting the piston rings and consequently the cylinders. That was going to cost a lot of hard cash later on in Meshed. No tourist ever ventured along these routes and the few tribesmen on their horses had difficulty in controlling their steeds which got bouts of nerves at the unusual sound of a mechanized vehicle.

At every village the question was: ‘Has Mr Nejjari been by?’ – to little avail. Just then a Jeep drove up. At the wheel was a certain Ahmedi who had learned that foreigners had been looking for Nejjari. His Jeep was old, its steering wheel was loose and the tyres were in an awful condition. He looked much older than his 30 years; an impetuous person who acted on the spur of the moment and took life easily. He piled everyone into his Jeep. Ahmedi was a good driver but you sat bolt upright and said your last prayers. His Jeep took corners at greater degrees of inclination than you would think possible. Then he would barge off the road into the desert, drive after terrified Turkmen riders whose horses were trying to throw them off their backs, and laugh loudly while the poor Turkmen would swear and get into contortions.

There was going to be a big wedding, said Ahmedi, and horse-racing too. A rear tyre got a great big hole in it, and the spare did not look very healthy. Outside a village a slim Turkmen woman in red stood in the middle of a field. Ahmedi in a joking voice asked her if she had seen a Jeep, obviously more interested in her than in the answer that was not forthcoming anyway. He shouted back to her that she was very nice and he wished he could … The word he used was the same in Turkish. When Mehmed showed signs of understanding, he looked up and said, ‘Be careful otherwise the men will cut your throat’. Mehmed believed him.

Another Jeep now arrived – it was Nejjari. He was a quiet man, with short grey hair, and, with his rifle, he looked like a typical traditional landlord. He spoke little but knew when to laugh and joke. He was a good shot, a good driver, much saner than Ahmedi, but even more courageous when it came to shouting at women in the fields that ‘he would die for them’.

At Pishkemer he told people to kill chickens and grill them, and sent Ahmedi to fetch vodka. Everyone sat down to eat and drink, and afterwards, with almost childish pride, Nejjari wanted Mehmed to watch him shooting perfectly, and laughed for minutes when a small girl started crying when Mehmed wanted to take her picture. Afterwards he jumped into the Kombi and showed his guests a school that was being built for a village at his expense.

Next day the poor Kombi was moaning and groaning. A trip to what passed for the local Volkswagen dealers to try and locate the ‘strange’ noise in the engine came up with the same old story – the piston rings and the cylinders were kaputt! There was nothing anyone could do but pour in litres of oil as had happened in Russia and press on in hope.

In the small Turkmen village of Sulfiyan the new arrivals and their long-suffering vehicle were greeted by the sound of the pipe and drums of wandering musicians. An acrobat did cartwheels, and then went around the onlookers with his cap, telling them how good he was. People sat ranged round the room with a solitary oil lamp in the middle. Two musicians perched on cushions played traditional Turkmen folk songs. Shadows flickered on the walls. Smoke fumes gradually filled the room. Villagers peered through the closed windows. This entertainment had been laid on especially – no other Europeans could have been so privileged. Nigel taped the whole proceedings, and the villagers were thrilled to hear it played back and asked again and again for a replay. Crowds of boys pushed each other through the door in their eagerness to listen to this weird machine. Nigel tried to change the tune and played them the ‘American Patrol’ from the Glenn Miller Story. ‘Did you like that?’ ‘Yok, Baba,’ was the dismissive reply.

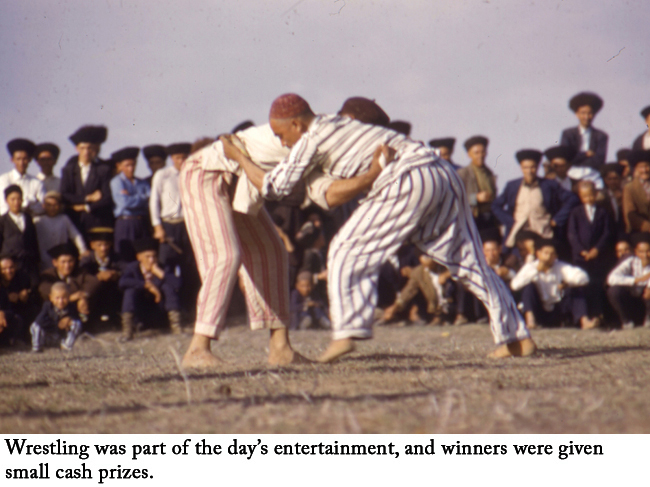

Suddenly a man’s raucous cry called everyone to come and watch the wrestling. Everyone joined the throng in an open space. It was now pitch black and only the rays from the moon gave light to the scene. The contestants looked ghoulish as they waltzed round, kicking up dust and sand onto the spectators. They grimaced as they strained for supremacy. Three or four of the elders wielded sticks and whips to keep the crowds from closing in too much. Shouts and cries greeted the sweating wrestlers as they pirouetted in the dust. Often the apparent loser jerked his feet to bring his opponent down with a thud.

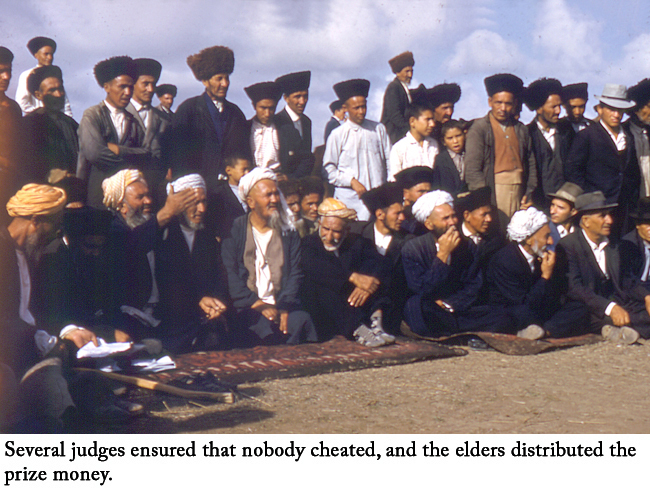

At six in the morning a wake-up call of drums throbbed throughout the village. The sun pierced the early morning mist. The horses were being loosened up and already men were dancing to the pipes and drums. ‘The Big Day’ had come, with horse-riding, wrestling, dancing and – a wedding. Small groups of men stood around the beautifully groomed horses with cloaks over them to keep out both cold and heat. A large circle formed and the wrestlers started the morning’s entertainment. Then came the horse-riding around a one-kilometre circuit. The winner of each race got 50 toman for each circuit completed; the last race of the morning was eight times round the course and the winner got 400 toman (then £18). The whole day’s entertainment, including the wedding itself, cost the bride’s family about £800. The setting was perfect – an endless plain with a few low sand hills seen through the horizon’s haze. At the finishing posts a crowd of about 2,500 people had gathered, most of them standing, some sitting astride superb horses. A group of elders sat with the prize money in envelopes in front of them on the carpet making sure no one cheated.

Excitement mounted at the first race. Several riders were disqualified for cutting the staked-out corners. Once or twice a rider-less horse would come thundering in, having thrown his young rider at a corner. The inevitable happened when a rider, unable to turn his steed in time, galloped straight into a cluster of men sitting on the ground, badly cutting one man’s head, wetting the sand blood-red. No women were to be seen. No human description could adequately portray this superb panorama of men and horses sharply outlined against the desert and the clear Persian sky. When the races ended, Mehmed, Nigel and Tony climbed onto sweaty horses to have their photos taken.

Back at the village more innumerable cups of tea were drunk before a rice and kebab lunch, followed by bowls full of grapes. This oppressed Turkmen minority could not have been more hospitable. The foreign guests ate first, and the remains were for the other guests, who sat round the bowls swooping up the rice and meat with their fingers. After lunch an animated general request brought the tape-recorder out for a new concert of the previous night’s music. Then everything subsided into a quiet hour. Later came the opportunity to give the locals another surprise as three young men got out their stove and started boiling up some washing. The women looked up from their wooden fires on the ground, amazed. Given the Kombi’s sickly state it made sense to leave later when it was cooler for the engine. As it drove eastwards into the gathering gloom, mountains closed in all around with fertile land covering their slopes. At a babbling brook in the shade of the trees water containers were filled. The full moon rose above the mountains. Minor oil troubles punctuated the journey as the Kombi was nursed along. The sleeping town of Bojnurd emerged out of the gloom just before midnight and the darkness made finding the address for a promised night’s stay at Reza’s house a hit-and-miss affair. By then midnight was past but the door was opened. Such was the sense of hospitality.

Next morning Reza, the 18-year-old host, was mustard keen to show his guests around the town and countryside. Everybody embarked in his Jeep, with three of his young friends, to drive to his country house, outside the town in an orchard of apple trees, grape vines and tall poplars. Grapes, apples and fresh walnuts garnished the table and at a local flour mill, where a stream drove the wheel, an old Kurd and his wife poured in the wheat grain and collected the flour in dirty sacks. Flour covered them from top to toe as they worked in almost complete darkness.

‘Would you like to swim?’ Further south appeared a veritable haven of an oasis in the desert. There was a tomb of an old ‘lord’ of Bojnurd, in the form of a mosque, surrounded by large, shady trees. At the foot of its steps was a pool of deep, clear water, full of enormous trout. A wonderful opportunity to strip off, dive in and swim across to the rocks and the source, a spring. It was paradise. In the shade, under the leafy trees, the local Kurdish women in long, black pantaloon-trousers under their dresses, hid behind chadors and did their weekly washing. Then back to the orchards to lie under the trees on an enormous carpet, drinking tea from a samovar and listening to recordings of Moscow jazz and Turkmen wedding music. Another recording was added of one of the boys singing and talking. They loved hearing their own voices.

It was a black night on a bad road and eventually a makeshift campsite was set up in the middle of a cold, windswept plain. Nigel and Tony shivered all night despite layers and layers of clothing. By the morning Tony felt feverish, glad when dawn broke and he could sleep fitfully for an hour or two. Mehmed, typically, had slept perfectly.

Arriving in Meshed at noon, they cruised around in search of the power station, where the department boss, Mr Harari, would, hopefully, be their host for a few days. Sure enough, he invited them to stay and dump their kit while the Kombi was being mended. He was head of the electrical department. He and his Armenian wife, who spoke the worst Russian Nigel had ever heard, and three children had a bungalow on an estate nearby. After a good lunch, Tony, a little ‘off’, lay down while his temperature climbed to 103. Mehmed sat with him while he sweated it out.

Meshed, Iran’s holiest city, once its second biggest, had sunk to fourth place in 1961. Mehmed and Nigel got the Kombi mended – £28-worth of damage – with a new shock absorber, piston, piston rings, etc. Tony, meanwhile, meandered across to the estate’s dispensary where he almost fainted, and they laid him down and gave him three penicillin jabs and various tablets and pills. He went back to bed for another sweat. Tony rose from his sick bed the following afternoon and helped, or possibly hindered, the packing up of the Kombi. The whole family had been very kind, especially the wife of Johnny, our host’s best friend. There was a terrific mixture of nationalities – Scottish, Armenian, Iranian and others. She was part-Armenian, part-Syrian. She wanted Tony to stay in Meshed where she would find him a nice girl for a wife. Tony asked her just to find him a nice girl, and not get carried away by such complicated things as marriage. The next day they wanted to make an early start from Meshed, anxious not to miss the bushkazi in Kabul – the national game of Afghanistan due to be played in honour of the king’s birthday.

But Tony still wanted to see Meshed, so off the three went to the centre of town, to the famous mosque and shrine of Gauhur Shad. On trying to walk straight into the mosque they were stopped by the faithful. After much talking and Mehmed swearing madly that he was an extremely devout Muslim, he was allowed in, in the afternoon, when there were no prayers being said. Nigel and Tony were jealous, but had to make do with Mehmed’s description of the holy place.

They left Meshed soon after noon, Tony lying in the back all the time, feeling acutely aware of every bump encountered on the terrible road. They missed their turn-off and were racing down the road to Teheran until some lorry drivers put them straight. Midnight came, and time to camp. It was cold in the night and someone had a revolutionary idea of how to use the tent to its best advantage. Instead of sleeping in it, they put it on their camp beds, and then folded the other half back on top of them. Not the brightest idea as it turned out.

On 1 October in Yussofabad, on the Iranian-Aghan border, they met a German student who had just driven from Kabul. He brought good news – the Khyber Pass was closed to all normal traffic but was still open for tourists. What a relief, both as regards money and time – Delhi could now be reached by 12 November as originally planned. The Iranian police and the customs took their passports, and all looked straightforward. The police chief, however, was in the middle of his afternoon siesta, so they had to wait a few hours till he shook off his sleep and was ready to sign their papers.

Off into the 10 miles of no man’s land with, for company, the occasional long camel-train. A solitary white stone with ‘Afghanistan’ written on it in English proclaimed that at last it was there. A few more miles later over the dasht (desert) was the Afghan customs post. It was already 5 pm. Private vehicles had to stay the night at the border ‘hotel’ as this was a military zone open only from dawn to dusk. The customs officer seemed to have no problem with the story of the stolen carnet but extracted a solemnly worded letter promising that the Kombi would not be sold in Afghanistan. The camp-beds were spread out on the floor of the hotel, and it was time to cook up one of the Expedition’s famous ‘gruels’ – a packet soup, two handfuls of dehydrated meat, an Oxo cube, salt, pepper, some spaghetti and water. Tony was now succumbing to the dreaded fever again.