11

TESTING AFGHAN PATIENCE

Up to the border, the road had been little more than a cart track; inside Afghanistan it disintegrated into wandering sand ruts, bordered by patches of desert scrub. Nights in Afghanistan were bitingly cold and Tony’s fever persisted. These factors and the cheapness of Afghan hotels led to abandoning camping for most of the stay in the country.

Along the sandy roads only an occasional bus or lorry came the other way. Herat produced a doctor – trained in Paris. He prescribed more penicillin jabs, more tablets and pills, and plenty of water for the suffering patient. Tony was to spend most of the next few days in bed.

The only hotel in town was very pleasant, set at the end of a tree-lined avenue amid flowerbeds and tall pines. It was a fine reflection of Afghan contradictions; the beautiful gardens were obviously intended for a high-class hotel; but the building and rooms were dilapidated, and services were non-existent. But it was cheap and so it was an opportunity to be rash and book a room with beds at 3 shillings and 8 pence a night (a fiver in today’s money) each. Some New Zealanders, who had just driven over the southern route, had bashed up their car and were trying to sell it. An interesting Dutch-Australian had sold his motorbike in Kabul and flown across to Herat to escape the clutches of the police. They confirmed that one could get out via the Khyber Pass.

Russians were everywhere. About 320 families of them lived in Herat where they were mainly involved with building roads and bridges, but had not got very far. Some of the shops now had signs in Russian, as well as Farsi and Pushtu, and many in English also. It later emerged that many of these Russians were there for a very specific purpose – to buy up dried fruits, especially grapes, which were being flown out at the rate of 12–15 plane-loads a day. The only other Afghan exports were wool and skins. There would be more encounters with Afghanistan’s Russians in due course.

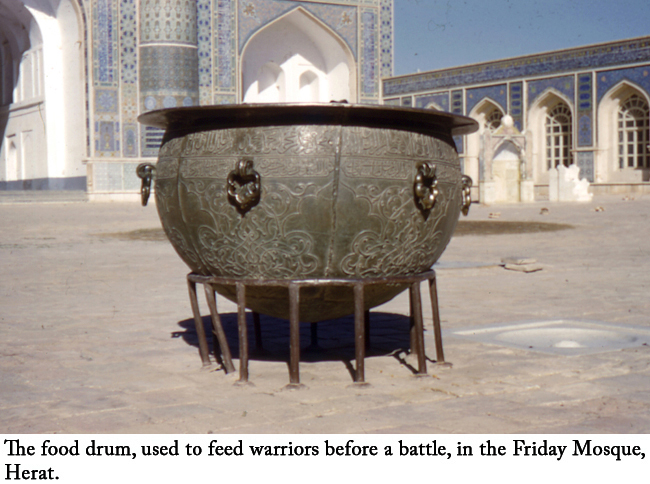

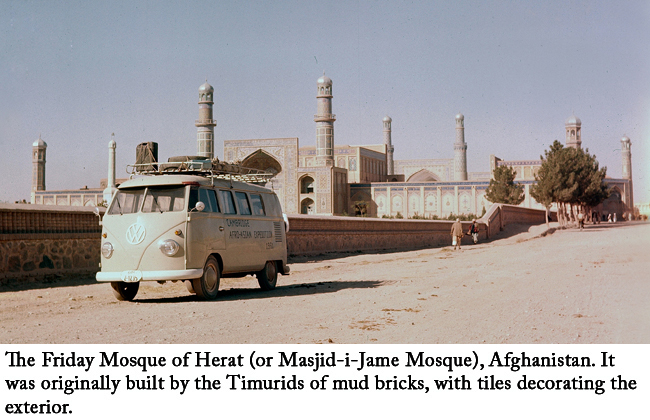

Herat was once the capital of the Timurid Empire and was a centre of learning, art and religion, but it had declined greatly during the past two centuries. The Friday Mosque of Herat (or Masjid-i-Jame) was originally built by the Timurids of mud bricks, with tiles decorating the exterior. A huge food drum, used to feed warriors before a battle, was among its prized possessions.

Sitting cross-legged next day in a chaikhane and drinking tea provided a good vantage point for watching the activities in the local market, with everyone shouting their wares. Occasionally someone lost their temper which was the sign for a few ‘fisticuffs’. Fruit was cheap. One kilo of grapes, two of tomatoes and some pomegranates (and plenty of bread) came to a total of seven Afghanis – just 1 shilling.

Afghan ponies pulled along the numerous, colourful and highly polished gharies, or carriages, at a tremendous pace. A curiosity trip to the Russian compound in the back seat of one of these gharies proved precarious in the extreme and one had to hold on for grim death. The Russians were not at all unfriendly, but no one paid any attention to their casual visitors, not even to ask them what they wanted.

Back at the hotel the manager was more than happy to buy 25 tins of coffee, from the Expedition’s original English supplies, at 30 Afghanis a tin, so providing enough petrol money for a while.

An Afghan aged about 22, Nasser Hanefi, who sat in the hotel foyer playing his portable radio – usually tuned to Radio Ceylon – seemed very hurt at not being spoken to more often. He seemed to think he would be taken in the Kombi to Kabul, his home town. The Kombi’s crew was equally certain he wouldn’t, owing to its overload and the rough roads ahead. He would soon make a pest of himself.

The Prime Minister had two years previously issued an edict to the effect that all women were to discard the chador, or rather at least the part that completely covers the face. But women still to a large extent wore this kind of visor, through which one could just glimpse the outline of their eyes. Iranian women were less inclined to wear this visor-piece. Few in Kabul itself did, but outside the capital it was common.

In Herat Mehmed and Nigel tried to persuade the police and the Governor to allow the Kombi to travel the northern route to Kabul, across 300 miles of desert. Apparently an American boy and a Swedish girl had been killed there a few years earlier so the answer was ‘no’ – even though some Oxford blokes had come through that way in a Land Rover a few weeks before.

On a drive out to the Mosalla (mosque) of Gandar Shah, Mehmed and Nigel climbed up the only surviving minaret of this once imposing building, claimed by many to be the finest edifice of the Muslim world. Eighty years earlier all the minarets partly stood, though in decay. In the face of a threatened Russian advance from the north, all buildings likely to afford cover to the enemy were demolished, under the advice, if not the direct order, of the British. So perished, but for its minarets, the Mosalla. Two of its four minarets were destroyed by an earthquake in 1932; a third had fallen down about five years earlier. Only one remained to illustrate the glory of the whole building. The dome of the shrine, still preserved, retained its beautiful form and some of its magical colour – a cross between deep blue and green. The young trainee mullahs from the Madreseh were terribly eager to help the visitors, and about ten people followed each other up the minaret like flies climbing a wall, some 250 feet high.

To Kandahar

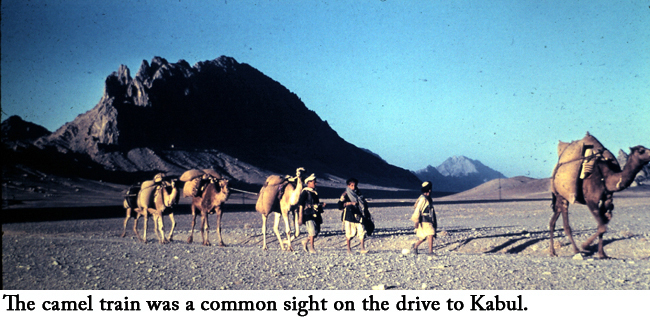

Along the Russian-built tarmac road, by-passing a new bridge the Russians were putting up, the Kombi suffered a puncture, and became almost stranded in the deep, soft sand on a ‘detour’ off the main road. Even in two years of roadworks the Russians hadn’t got very far, and soon the Kombi was twisting and turning and bumping along the narrow ‘road’, past occasional little villages of flat-roofed, mud houses clustering amid groves of green poplars on the bare hillside. There were no railways in Afghanistan, so it was just as well the roads were gradually being improved; road and air travel were the only two reasonably fast methods of transport, compared with donkeys and camel trains.

Two more arrivals after midnight stretched the patience of local hoteliers, first in Farah and then in Girishk, where the annoyed hotel proprietor needed much persuasion to open the door. The next morning was a good occasion to wash some clothes by boiling them up in a ‘Dixie’. Just then the needle in the stove broke, leaving everybody, so to speak, stoveless. Nigel gathered a collection of tools and set to fiddling around with the nozzle, all of which provided him with yet another worry for his already careworn brow.

Mehmed and Tony drove into town along the main street, which was lined on either side with small, often colourful open shops selling almost every imaginable commodity from grain and tea to Japanese teapots and Russian hats. There was a definite lack of fruit, especially grapes and tomatoes, which were becoming part of the companions’ basic diet now; they filled themselves up with naan bread instead. Most of the men were Afghans in their long, loose shirts coming down below the knees and sandals, plus individual variations like pullovers and old army jackets; all this crowned by a turban, frequently embroidered on top with brilliant silver and gold thread. Mehmed and Nigel intensely annoyed a camel-driver by driving up and down the main street four times while looking for some tomatoes, disturbing his beast so that each time they passed it ‘got up’ and the driver had to continually coax it back down onto its haunches, a procedure which became increasingly arduous as time went on.

Arriving at Kandahar in the cool of the evening of 8 October, the companions found a guard standing outside the hotel. There was room to be had and herded together in the lounge were eight Russians. They were buying dried fruits. Asked where one might eat, they had no idea. Finally, down a dark street emerged quite a clean place, a former barber’s shop, run by an Uzbek who had come out from Bokhara many years ago, travelling rough by mule and horse across the mountains out of the USSR. He had come via Kashgar and Sinkiang in Chinese Turkestan, taking 15 years to cover a distance of 1,000 miles. He, his son and a friend were very welcoming and everyone sat for hours talking, eating kebab off spits, with bread and chai. The proprietor provided addresses of his friends up in the north of the country for the trip that Mehmed, Nigel and Tony proposed from Kabul. After supper they bought a melon from an Afghan sitting cross-legged in the middle of his fruit, his face lit up by a swinging lamp and his birds twittering in their covered cages.

The Americans were in the middle of resurfacing the main road; the police were having great fun keeping the locals off the new tarmac. Tony wanted to cash a traveller’s cheque but the bank, it seemed, didn’t open until the afternoon. He and Mehmed went for a walk instead via some ruined buildings, which appeared to be one of the city’s public conveniences, up a narrow, foul-smelling road to the bazaar. In a sort of antiques shop Tony fell in love with an old Russian knife, reputedly from Bokhara, and 200 years old – but US$20. It looked genuine enough, so back they went to the bank to await the usual slow method of changing money. A fellow with a shabby uniform and a sleepy face showed them into the manager’s room. Portraits of Premier Daud and the king, a desk, two easy chairs, a map of Afghanistan and a short, fat manager were the total contents of the room. The ceiling was so low that Tony, all six foot plus of him, had to bend forward in order not to break his neck. Changing a $10 bill was a horrendous process. All sorts of papers had to be signed, passports shown several times and one’s name spoken loudly so that it could be written down in Farsi – as Anti Jan Tomson, Ingilizi.

The town had no set plan – buildings and streets ran haphazardly in all directions. Half-naked, barefoot children followed everywhere; noisy coppersmiths beat out their masterpieces; kebab sellers blew the smoke away from their grills, while fruit sellers nibbled their own grapes. Before getting to the hotel Mehmed was seized by a vital desire to relieve himself. The locals did not understand his agitated enquiries for a toilet, until one youngster led him through a narrow alley to a path by a stream where, quite undaunted by the local women passing by in their chadors and a running commentary kept up by some children, he did what was necessary.

Once back at the hotel, the dreaded Nasser – who had turned up from Herat – elected himself guide and everyone drove out to some rather pleasant gardens and small waterfalls outside the town. After an evening meal at the Uzbeki ‘barbershop’, on returning to the hotel, there was Nasser again, who proceeded to get well and truly drunk, insisting all the time that he was coming to Kabul with everyone in the Kombi. Again he was assured that he was utterly mistaken! Then he changed his mind and promised Mehmed any amount of money if he would go to his room. Mehmed went, for the hell of it, but soon returned without even one Afghani. Nasser admitted that many Afghans, himself included, much preferred boys to girls, mainly because you could ask a boy to your home but not a girl. At midnight, Nasser woke everyone up and threatened to kill Tony if he went to his room.

They paid the bill and sped away from the hotel and their drunken friend early in the morning. The road was good asphalt, and when they arrived at the airport, there was a road junction with a rather worn signpost. It did not look worth bothering about so they sped off down the asphalt road which the Americans were busy making, past the houses of the ICA (military Intelligence Corps Association) people. Living with their deep freezers, with their bourbon, especially compared with the more adaptable Russians, the Americans left unfavourable impressions on the Afghans. They isolated themselves socially and in Afghan eyes they lived pretentiously. Quite apart from the standards to which they were used, perhaps these were also sorts of defence mechanisms.

On out past the new International Airport and still the surface was excellent. That was odd – the New Zealanders met in Herat had said that only 15 miles or so was asphalted; surely even Americans could not do 15 miles of road in a week. Just over 60 miles later, a barrier suddenly appeared across the middle of the road. It emerged that instead of heading north-eastwards along the road to Kabul the Kombi had gaily sailed down to Spinbaldak at the Pakistan border. In addition, just to make it a really good day, they ran out of petrol, incurred two punctures, and had to toil through the midday heat to mend them. While Nigel struggled with the ‘help’ of some of the locals, Mehmed and Tony sat down in the chaikhane to fine tea flavoured with dry lemon leaves. At last both wheels were back on and appeared to have more air in their tyres, a little petrol was cadged, and so they drove all the way back to Kandahar.

On to Kabul

After a hearty meal and fill-up, they set off for Kabul, this time deliberately turning left at the signpost. It soon got dark. Every now and then the road would abruptly diverge to right or left and go down a short, steep incline, thus avoiding a bridge which had long since caved in. One needed to concentrate very hard in order not to carry on over the non-existent bridge. At Kalat two American boys and a Spanish girl in a Citroen 2 cv caught up with the Kombi – its inmates were maliciously pleased to hear that the deuche crew and two Germans and two Dutch boys had also gone down to Spinbaldak by mistake.

After getting into Mukur at 2 am, Mehmed and company were stretched out contentedly, if not exactly comfortably, in the four-storey national hotel, with still a bed spare in the room, when the local bus rolled into the yard below, and two English journalists from Teheran burst in, as well as an Afghan army officer. They were all looking for somewhere to sleep. The officer grabbed the spare bed.

They awoke next morning to a superb sunrise flooding the scene over Mukur with its backdrop of the Ghazni mountains. It is almost impossible to describe the morning beauty of the high Afghan plateau. The crisp blue air outlined every shade and detail, as if on an artist’s canvas, against the background of the cloudless sky, the brown hills, the yellow villages and the green trees. The bus left again at 6.30 am so the ‘friends’ didn’t get much sleep. Once awake, the Kombi seemed to be sulking and didn’t want to work. Nigel almost crawled into the engine in an attempt to diagnose the trouble. The solution was relatively simple; Mehmed suddenly decided it was lack of petrol, and, lo and behold, once the reserve was turned on, she worked. After they had filled up with petrol, the inside of a chaikhane revealed the American and Spanish friends of the previous evening who were eating. One of these ‘characters’ was Mathias Opersdorff II from Rhode Island, the smallest state in the USA. He strode along the road, all 6 feet 5 inches of him, a karakul hat perched on his head and two cameras hanging round his neck. He subsequently became a professional photographer. At one time later he left his London black cab at Tony’s house having spent three months on the road with the travelling people or ‘tinkers’ in Ireland, and subsequently wrote an article about the experience for the National Geographic. He was the son of an Austrian count, who could trace his family back to at least the thirteenth century, and a mother whose ancestors went to the USA on the Mayflower. His parents met in Paris and fled to America in the 1930s in revulsion over Hitler’s policies.

Trying to reach Kabul that night, Mehmed, Nigel and Tony were soon bumping their way on to Ghazni, too late to look round this particularly old, historical town. It got nippy at night, not surprising at 7,400 feet above sea level – 1,400 feet higher than Kabul. Dinner that evening was in what at first sight appeared to be a very ordinary restaurant, but which turned out to be the meeting place of just about all the possible racial mixtures in Afghanistan – Pashtuns, Uzbeks, Tadjiks and Hazaras being among the main ones. Good kebab and bread were brought, washed down with tea, and enormous platefuls of grapes. The locals here, as everywhere else in Afghanistan, repeatedly got out their little round tobacco tins and took a pinch of naswar – an extremely powerful stimulant. It was of a greenish colour, and was administered either as snuff up the nostrils or in a pad under the tongue. It smelt vile, but it was very cheap, and was the most popular and widely used drug in the country. On the way out of the town Afghan Radio was blaring out anti-Pakistan propaganda in English.