12

KABUL BEFORE THE WINTER

Only 6 miles to go to Kabul. At last the few flickering lights of Afghanistan’s capital appeared across the dark plains. As midnight struck, Mehmed, Nigel and Tony drove slowly down the main street of Kabul. The engine’s roar echoed eerily as they hunted through the deserted streets for a place to stay. A solitary figure stood on a street corner swathed in blankets against the sharp night air. ‘Hotel koja?’ Nigel shouted in faltering Farsi. Half an hour later they were thankfully installed in the Maiwan Guest House for 15 Afghanis, the best doss-house in town.

Austere Kabul was a small town with an animated history at the centre of one of the world’s major platforms of contest – Afghanistan. Yet Afghanistan was never really a state, rather a collection of mutually suspicious fiefdoms. A first taste of this suspicion was evident the next morning when Mehmed, Nigel and Tony hotfooted it to the Afghan Tour office, the first tour operator in Afghanistan, licensed by the government. It operated a bit like Intourist in Moscow, in that all tourists had to have agreed itineraries.

The Turkish Embassy now turned up trumps with an offer of space in their compound. Once a royal palace, the embassy was quite old. It had an Ankara cat which, like all its breed, had eyes of different colours; a proper specimen, it seemed, had to be deaf as well. Mehmed and the Ambassador, Mr Talat Benler, hit it off very well. A little room round the back of the embassy provided a long overdue opportunity to unload and sort out crumpled and scruffy gear. Within an hour the empty room on the veranda was graced with a carpet, four chairs and a table, with a toilet and wash-basin next door. The ambassador and his wife, a charming couple, speaking faultless English, despite a five-year sojourn in the States, set extra places for lunch. In the middle of lunch in walked a long-lost first cousin of Mehmed’s – Lütfi Coşkun. A little later in came a member of the Turkish military junta that instigated the coup in Turkey in May 1960, but who fell out with the rest and was exiled – a certain Colonel Akkoyunlu. The junta had put all the Democratic Party members of parliament – including Mehmed’s father – on the prison island of Yassıada near Istanbul. Soon after the coup Akkoyunlu and 13 other renegades were sent away from Turkey to various embassies as ‘consultants’.

At the Ministry of Education the Head of the Secondary Schools Department, in a mixture of French and English, said he would be only too delighted to help the Expedition’s studies – ‘just write out a questionnaire’ – like a good bureaucrat anywhere.

Back to Afghan Tour for visa photos. A large collection of fellow travellers were hanging around, including two Dutch boys already met in Moscow, trying out the new Dutch car, the Daffodil, and the two English boys who had appeared out of the woodwork at Mukor. Outside was Colonel McLean, the cousin of one of the Expedition’s patrons, Sir Fitzroy Maclean, author of Eastern Approaches, to this day still the greatest travel book of the 1930s. He was to be very helpful.

The embassy of the British, who more than any other outside power had burnt their fingers in Afghanistan’s turbulent modern history, was in a very large compound some way out of town – that was probably a useful extra margin of security. It was a large, grand, white building, beautifully situated and furnished. Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India, had been responsible for all this splendour. Now that finally, he had said, the British were to have a permanent mission in Kabul, they should ensure that it be the most magnificently housed. This was in the 1920s, just prior to the Third Anglo-Afghan War, or the War of Independence as the Afghans call it. The Ambassador, Mr Gillette, had dwelt beyond the mountains, so to speak, as Representative in Sinkiang for many years, and several valuable maps and antiques of that area adorned his residence. David Hannay, the 3rd Secretary, was an old school friend of Nigel. Suave and sharp, he would in due course become one of Britain’s outstanding diplomats, including stints as ambassador to the EU and the UN and tasked with trying to sort out the intractable problem of Cyprus.

Tony and Mehmed were standing quite innocently outside the Kabul Hotel waiting for Nigel, when a rather attractive girl walked by with her escort. They paid her the due amount of admiring attention that she deserved. She quite rightly ignored them and just carried on walking. Her escort obviously hadn’t liked this unwanted attention as he came back and, swearing something in Farsi, pointed his fingers in a V-sign just short of Mehmed’s eye. Mehmed and Tony were too surprised to do anything for a moment. The lady dragged her escort away just before everyone became aggressive.

Colonel Akkoyunlu and his daughter set up a tour of Kabul’s highlights. The late Nadir Shah’s mausoleum, set on a hill, dominated the city. A soldier on guard kept beckoning rather slyly. He wanted money in return for letting anyone take photographs. At Babur Shah’s Gardens and in front of his tomb a national scout jamboree was just about to take place. Various hectic scout-type activities rampaged, from putting up tents and roping off fences, to making every manner of wooden structure, such as tables, chairs and cupboards. Scouting in Afghanistan was new, with about 600 boy scouts and 400 girl guides, and growing in popularity. Somehow it felt culturally out of context up here on the high Afghan plateau. The campsite was meticulous and tidy; whether it would stay the same way once the jamboree got going was another matter.

Western facilities abounded. An International Club, with a cosy little clubhouse, in Shehr-i-Nau, the new city of Kabul, swarmed with Germans plus a few spare French and Americans. Western-style houses were large and expensive; shops sold Western groceries and canned foods at prices that had become even more exorbitant since Pakistan had closed the border; coffee, washing powder, cornflakes; anything you wanted, at a price. By stark and gaudy contrast, in the bazaars the old city impinged on the new. Narrow, labyrinthine streets; tiny stalls, one tended by a cross-legged little boy who bargained like a fully fledged tycoon; noise, colour and squalor. Curious eyes followed the strangers here. Veils were lifted to allow a quick glance, and then hurriedly dropped again.

Mehmed, Nigel and Tony had deliberately forced the pace of their journey to Kabul in time for the celebration of the king’s birthday, at which the national game of bushkazi was normally played. Alas, it hadn’t taken place for at least two years, owing firstly to the large number of people killed, and also because of some alleged disease of the horses in 1961. Bushkazi is a game between two teams, which do battle on horseback to get the carcass of a goat over their opponent’s line. They each have a whip, partly to ‘stimulate’ their horses, and partly to attack their opponents – not a game for tender souls. It is in fact not an Afghan game as such, but came down from the Central Asian tribes, including, in Afghanistan, the Turkmen and Uzbeks. ‘How about a basketball match instead?’ asked some joker. There was an alternative – try and get permission to go up north and see a game at Mazar-i-Sharif, where the season was just beginning. This was to be the source of major headaches.

The generosity of the Turkish Ambassador and his wife in offering frequent lunches or dinners provided a welcome alternative to the repetitive Expedition diet of gruel, alternating with spaghetti and dehydrated meat. A good briefing was had over pre-lunch whisky and sodas on the lawn of the American Embassy with its 1st Secretary, a tough, pleasant ex-Marine, who walked with a permanent limp; he had been badly wounded in the leg in the Korean War. Mehmed earned his lunch one day through interpreting services rendered in a discussion about Turkish politics between Colonels McLean and Akkoyunlu. Mehmed’s cousin, Lütfi, not only offered dinner every evening at his house, but acted as chief salesman of the Expedition’s surplus coffee, chocolate, shoe-polish, spaghetti and porridge, as well as obtaining letters of introduction for the still evasive trip north.

A certain Dr Kardesh, the Turkish doctor in charge of the World Health Organization (WHO) anti-malarial campaign up in Kunduz, some 150 miles north of Kabul, happened to be in the capital. Mehmed dropped in on him and his wife: ‘Come and see us when you reach Kunduz.’ At the British Embassy the Military Attaché, a typical ex-RAF officer, but without the appropriate moustache, provided good tips about the road conditions up north, and what to look out for.

The police had said that visas to travel up north would be ready by early afternoon. Police headquarters were in a huddle of buildings in a large compound, the visa office in a little shack by the main gate, manned by a grumpy functionary. Only Mehmed’s visa was ready. The British, for political and historical reasons, were anyhow not at all popular in Afghanistan. It also turned out that our travellers’ by now much-thumbed general visas for Afghanistan had all expired a few days previously. The final decision concerning Nigel and Tony rested with the Foreign Minister or even the Prime Minister, who was the real stoker of anti-British feeling in the country. No one could get to see either of them anyway. Maybe the British Embassy could take the matter up? The Turks, however, who were pretty well in with the Afghans by comparison, were not so sure that it would come off at all. So nobody would get to Mazar and Balkh in the north, which, according to travellers from the past, was easily the most interesting part of Afghanistan.

Over early evening drinks or ‘sundowners’ the British Ambassador, with commendable frankness and lucidity, described how the reasons for anti-British feeling in Afghanistan were three-fold; firstly, for the historical reasons of the three Afghan Wars; secondly, for the fact that in the old days when Britain was in India, she gave aid to Afghanistan, but now she couldn’t afford it, or anyhow was quite prepared to let America give money instead; and thirdly, there was the Pakistan border problem. You could blame it all on the British – so perhaps Nigel and Tony were being made useful scapegoats. Mehmed now went off on his own to see the unhelpful, obnoxious character in the visa section. Armed with an Expedition prospectus and a copy of the local newspaper with everyone’s faces smudged in it, and suppressing bloody-minded instincts, he set off. Time dragged. Two hours later he was back. It was the same old story, neither a definite ‘no’ nor ‘yes’, but ‘come back this afternoon’. As a last resort David Hannay at the British Embassy was roped in to try and get an official diplomatic letter. It seemed Nigel and Tony were the first Brits to have suffered thus that year. It was frustrating – the great Hindu Kush right up in the north of the country beckoned. Mehmed subsequently returned empty-handed from another excursion to the police who now could not make up their minds whether everybody’s current visas had in fact run out or not. Mists of obscurity were closing in.

Kabul, up on the high plateau, ringed with mountain fastnesses, was so different from the rest of Afghanistan. Turbaned Pathans, a blanket swinging nonchalantly from one shoulder, clashed visually with their countrymen in Western dress. Large foreign cars, mainly American and Russian, hooted their way through clusters of gharies. Women, enfolded inside their chadors as in a chrysalis, shopping at fruit stalls, and schoolgirls in their black uniforms and white headscarves, exemplified the changing face of Afghanistan. The Kabul River, which flows through the whole city, was put to every possible use; camels, donkeys and humans drank from it; people washed themselves and their clothes in it; they urinated and defecated in it; they washed their lorries and plates in it; and they even swam in it when the melting snows and spring rains had filled it up.

There was a reason why women wore coats and headscarves, if not shrouded in a chador. Two years earlier when the liberation decree came out, women who took off their chadors were often attacked. So another decree was issued saying that they could not be touched if they wore a headscarf and a coat – that is, in public. Reports from Kandahar said that hundreds of people or more – the reported figures varied wildly – were killed in the ensuing riots. The girls’ school was burnt down and martial law proclaimed. In their own homes women could take everything off, if they wanted to. In public they wrapped up. Under the hem of the chador you could sometimes catch a furtive glimpse of the modern Western clothes of the wearer, short skirt, nylons and high heels.

In Kabul some school kids were educated in privileged surroundings. At the rather impressive Najat Lycée German was the lingua franca for the teenagers. The director, Hamidollah Enayat Seraj, happily showed off the classrooms, reading-rooms and library. The school had about 1,650 pupils and the student–master relationship and the standard of work were most impressive, even if everyone seemed to shake hands everywhere all the time, and classes stood up when visitors entered – just as they would do in Germany.

Another good example was the Malali Girls School, the largest girls’ school in the country, situated securely opposite the Ministry of Interior. The Directress, a strikingly good-looking woman, clearly in command, entertained Nigel and Tony in her spacious study. Everyone talked in French in their enthusiastic descriptions of the school, the subjects it taught and the general history of girls’ schools in Kabul. This was followed by a visit to various classrooms where lessons were in progress. Most impressive was the nursery and playroom for the teachers’ children, so that married women could return to their old profession. Tony could not help thinking that such supportive social practices could be profitably followed in England. Over coffee, cake and wonderful Afghan delicacies the Directress and some of her teachers almost palpably enthused about what they were doing.

Both these examples showed how, against many odds, education in Afghanistan could flourish. Some of the money might have been foreign: but Afghans were doing the job.

Not that education necessarily brought just rewards. Over tea and biscuits, Professor Mohammed Ali, one of the foremost Afghan historians and a lecturer at the university, provided some insight. His daughter was the first woman doctor in Afghanistan, having qualified in obstetrics and gynaecology in Pakistan and America. However, she had met a great deal of opposition before being able to finally set up practice. She earned only 1,500 Afghanis a month, while her father received 6,000 a month, and her brother, a newly qualified pilot, already got 5,000 a month. Such was the unimportance given to the qualified women doctors in Afghanistan, although there was an acute shortage of the medical profession in the country.

A nervous if rickety Afghan state toyed with vigilance. One day a Dr Dupree came to offer lunch at his house. He was an American archaeologist and anthropologist who had been in Afghanistan for the previous ten years with his wife. They related how in the Afghan police-state all servants of foreigners had to submit a report to the police about their employers’ movements, etc. The Duprees tried to treat this as a joke; Dr Dupree offered his waste-paper basket to his servants with all his old correspondence in it.

Meanwhile, Afghan people went about their everyday lives – including the business of getting themselves and their goods from A to Z. Throughout Afghanistan, even more so than in Iran or Turkey, the stranger paying his first visit to this country was forcibly struck by the gaudily painted buses and lorries. Mehmed was used to similar means of transport in his native Turkey. Nigel and Tony not only admired these ancient and colourful contraptions, but also marvelled at the enormous amount of goods and the number of passengers they carried at one time. Had they followed one for a while, they would probably soon have witnessed one of the numerous breakdowns that plagued these conveyances.

The police seemed little more, if at all, committed to their roles as guardians of public order than did those in Iran. While the Kombi was obediently stationary at some traffic lights which were still red, a local car shot by at speed. The policeman on duty vainly blew his whistle, the motorist not paying the slightest attention, so the policeman shrugged his shoulders and resigned himself to relieving himself behind his little red and white striped hut. Yet the Kombi was stopped a dozen times and its inmates quite rudely questioned about what on earth their strange German Zollnummer plates were all about.

It was time to take a broader look at this complex country. Drinks with the Turkish Ambassador provided deeper insight into Afghanistan in general, the political, economic, cultural and educational fields, as well as perhaps the most important sphere of all, religion, which still seemed to dominate so many questions in the country’s life. He had seen two looming developments in the north of Afghanistan: the discovery of oil by the Russians, and their plan of opening five or six experimental farms. He told the story of how the Afghan government had sabotaged a United Nations plan to improve water supplies to the people. Water was controlled by the government. If an uprising occurred it could easily cut the supply and the insurgents would be unable to resist for long. The UN was told to mind its own business.

The Ambassador talked of the heterogeneous character of Afghanistan. Understanding the tribal bedrock was the key to decoding the country. Out of a population of 8 million, 4–5 million were of Pashtu-Afghan origin and they ruled the roost most of the time. Constitutional lawyers were trying rather feebly to ‘fix’ tribal groups’ status by religious, social and other methods. The Turkmen, Hazaras and other Shi’a were in any case barred from high office. Most of the kings had come from a few tribes around the Kandahar area. The social structure and politics of Afghanistan, in spite of economic development, and with intellectuals studying abroad, brooked no communication of political ideas or sizeable opposition. It was an autocratic kingdom offering no alternative to this kind of rule. In 10 to 20 years’ time, said Mr Benler, with better communication, things might improve. They changed all right – but not for the better.

As for foreign policy, the government’s pro-Pashtu emphasis was not only dictated by the dominance of the 4–5 million Pashtu-speaking peoples in Afghanistan but by the existence of another 7 million Pashtu over the frontier in Pakistan. It was a ‘national’ problem; the only thing artificial about it was the porous Afghan-Pakistan frontier – the Durand line, named after the British official who in 1893 traced it straight through the heart of Pashtu country. The policy of balancing one power against another on the backs of the Pashtu harked back to the British ‘Great Game’ against Russia. Once the British left India, the Afghans felt quite alone, and tried to establish the foundations of their own foreign policy. In 1952, they asked the West for arms and economic aid. Russia, meanwhile, continued looking down from the north for an appropriate occasion to get in. With neighbours Iran and Pakistan developing, Afghanistan could not remain an island of poverty and ignorance. The West ignored the arms and aid request, despite initial US responses. Faced with no guarantee of Western aid, Premier Mohammed Daud Khan said Afghanistan would take aid from any quarter, even Russia, knowing full well the consequences. So the Russians moved in.

The Afghans still wanted Western aid. The government did not want to deal with just one power – they wanted both. When the Afghans launched their second Five-Year Plan, the Russians offered to foot the whole bill. The Afghan government refused and split it in two – half from the Russians and half from the Americans, the Germans and the West in general. The Afghans clearly wanted the presence of the West to guarantee their political independence and non-alignment.

Russia, said the Ambassador, had three advantages over the West: proximity; their sort of regime; and their way of giving aid through short- and long-term policies combined and adaptable to the conditions of the country. The Americans gave $40 million in aid, but spent $10 million on their ex-pat personnel; thus the Americans lived in relative luxury compared to the modest standards of ex-pat Russians. The Afghans noticed this and were not impressed.

The Russians had kept to their bargain, so far – an intelligent policy. At that time they sought not to impose, to avoid being overbearing. They bided their time and did not force the pace because everything was going their way. Afghanistan was a convenient shop-window of a benign Soviet Union. In time they would become more strident and risk upsetting this comfortable relationship only if they felt a threat from the Afghans themselves, or from others using Afghan territory and politics to upset their security interests, above in their sensitive Central Asian underbelly. For the time being the Russians perceived no such threat – only opportunity.

The big issue was Russian military aid, both the supply of arms and training. The Afghans would take such aid from anyone as long as the border problem with Pakistan remained unresolved (persistently both countries claim each other’s territory). Though much of their equipment was out of date, the Russians had supplied MIGs and were training the airforce. The Russians were also trying to get into education through the back door by military training. They had tried more straightforward methods, from offering to send teachers for an art school to actually building it (the Afghan government turned that offer down too). The Poles and Czechoslovakians also had teams on the ground. But Eastern Bloc teams clashed, as did the Western ones, through inadequate co-ordination of aid programmes. ‘The Helmand Valley scheme’ was a particular fiasco. The geological survey underestimated salty soil and bad drainage. The Russians made a quick impression with their kind of visible aid. American aid was longer-term but fewer people noticed.

Afghanistan, concluded the Ambassador, would not be lost to the West unless the West did something extremely stupid. And, he added, one had to bear in mind, both in internal and external affairs, the influence of the mullahs.

Subsequent events would bear out this analysis.

Autumn arrived very suddenly in Kabul, and when it did, it was breathtakingly beautiful. The reds, yellows and golds of the leaves stood out in sharp outline against the azure blue sky. Before long the first fingers of winter would stroke the city’s streets and hardened Afghan men would go nonchalantly in sock-less slippers through the snow in minus 15 degrees centigrade. But for the moment it was bliss.

The autumn sun warmed the stonework of the Kabul Museum, probably the best in Central Asia. The museum drew on a natural treasure ground of remarkable artefacts left by the civilizations that had dwelt in Afghanistan over the centuries. The upper storey had almost finished being redecorated and the various objets d’art were being recased with new lighting and were extremely well laid out. Much of the credit for this had to go to French archaeologists who were also digging, and had recently unearthed some wonderfully preserved old Buddhas, lots of pottery, urns and coins. Much of this wealth was to be plundered in the years ahead.

There was yet another frustrating visit to the police station; it now seemed highly improbable that Nigel and Tony would ever get visas. So Mehmed would go up on his own to Kunduz and Mazar. Hence at least one of the party would get there, and Mehmed could take plenty of photographs, and write his impressions when he returned.

Early on Monday, 23 October at the civil airport workmen were still hammering away at the new air terminal. In the background a new Russian cement factory blew out clouds of dust, which slowly rose into the clear blue sky above a semi-circle of mountains. While the companions were waiting in the chill morning air for Mehmed’s departure, five Russian planes touched down, presumably part of the daily airlift of grapes out of the country ... Soon afterwards Mehmed climbed aboard. With a roar of its twin engines the DC3 workhorse slowly lifted into the air and banked towards Kunduz and the north. With luck, Mehmed would be back a week later.

So to the police station for the umpteenth time. ‘No news – ring me up tomorrow.’

After the Kombi had been dumped at the garage for its 12,500-mile service, it was a good opportunity to stretch legs along the banks of the Kabul River, pausing at various shops to sample the merchandise, before turning down a narrow alley into the cotton and cloth market, where numerous small boys sidled up and whispered, ‘You want to change money, dollars?’ So on, past rows of shops where merchants were busy making hats and coats to measure, as far as the Russian Embassy. It appeared to be the only embassy in Kabul that kept its doors shut and barred; and certainly the only embassy with a woman doorkeeper, a big, well-proportioned, red-lipped Muscovite. Nigel wanted, eclectically and not without chutzpah, to read the unabridged version of the report of the much-vaunted ‘turning point’ 22nd Communist Party Congress held a month earlier in October in Moscow, after the Expedition had left. There, Khrushchev launched his plan to build ‘Communism in 20 years’, ditched the slogan of ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’, sealed the USSR’s break with China, and contrived the removal of Stalin’s corpse from the mausoleum in Red Square. Full reports of this controversial Congress were slow to emerge and a complete report on the proceedings of this Congress would not be made fully public until a decade later. Not everyone in Moscow was enchanted with the Congress results – Stalin’s spirit lingered on. No wonder that the red-lipped Muscovite was cautious about these unseemly visitors to the Soviet Embassy in Kabul. After a certain amount of questioning, Nigel and Tony were ushered into a dull little reading room and given copies of the two latest official papers on the subject. These sparse sheets set out the reasons that compelled Khrushchev to look after the peace-loving nations of the world by exploding his 22nd atomic bomb; and reading about the Berlin crisis. Maybe one day East and West, one thought, would see eye to eye, but it won’t be yet awhile.

On 26 October, while Nigel and Tony were busy cleaning the Kombi and clearing the veranda for an impending party, the Turkish Ambassador told them he had just received a telegram from Baghlan to the effect that Mehmed was being held in custody. There was nothing anyone could do. Mr Benler said he would find out what he could.

Meanwhile there were diversions.

Ron Stegall, the 23-year-old head of the administration for the Institute of Education, a big, balding fellow, full of ideas and with an immense appetite for hospitality, invited Nigel and Tony to an Institute picnic at a place called Istalif. Nigel would see a lot of Ron in later years in the USA. This was now a golden opportunity for getting out of the city for the first time in over two weeks. Istalif was a short way off the Bamiyan road, where Kuchi nomads were migrating towards Pakistan. Some were on the move towards Kabul with their camels and donkeys fully laden, while others were encamped in their black tents by the sides of the road. Estimates said there were as many as 2 million of them, but no one knew their exact numbers. Soon there was a glimpse in the distance of the whitewashed buildings of the ancient city of Istalif itself, set on a hillside overlooking the plateau below. The colours of the trees and bushes were breathtaking, binding in leafy wreaths all the possible hues of red to gold, orange, yellow and almond. At the hotel, set on a knoll overlooking Istalif, some ancient gardens were shaded by trees reputed to be 800 years old. From here, etched against the sky to the north, the distant view of the freshly snow-clad Hindu Kush range dominated the horizon. It was a surrealistically beautiful setting for lounging on carpets for a veritable feast of kebab, rice, pilao, fruit and tea.

Istalif boasted famous kilns for the delicate blue pottery of Afghanistan. At first sight this part of the town seemed like a ghost-village, virtually deserted except for the few people working in the potteries. The centuries-old industry was still carried on in its original crude form, hence possibly the terribly cheap cost of the products, priced at way below their true value for beauty, in the shops in the bazaar below narrow, twisting lanes, where booths and homes clung higgledy-piggledy and precariously to the hillside.

From here, too, the towering mountain wall of the wonderful Hindu Kush beckoned almost teasingly from its snow-covered peaks inaccessible to most human beings. Fingers of ice etched their artistry up the flanks in spears of white, silver, green and grey to where they touched sparse clouds vying for attention with the dazzling sun. Nigel and Tony gazed at those great mountains, almost as if in a trance. They were determined by hook or by crook (probably the latter …) to cross its snowy redoubt. The Hindu Kush turned out to be more powerful than them.

As they drove slowly away from this quaint old town, the sky turned almost blood-red, casting a reddish-tinged light over the whole valley and the surrounding mountains. This effect lasted only a few moments, but not before the red had diffused the pregnant snow-clouds, which were threatening to burst and shake out their white flakes.

Nigel and Tony decided to defy the powers that be, and set out next day for Bamiyan without permits. As they were leaving the town, a blue Mercedes overtook them and parked about 50 yards ahead. This rigmarole was repeated several more times, with more or less obvious excuses offered by the driver such as stopping to buy a melon. After an hour or so he disappeared. The automatic reaction was that he was a policeman sent to tail Nigel and Tony after their virtual ‘confinement’ in Kabul.

As far as Charikar, 40 miles north of Kabul, the country had been the dry and sandy landscape of the plain, with its great curtain-drop of mountains. Now the road turned westwards into a long valley with vineyards and poplars and wandering streams, awaiting their fill from the winter snows. Side valleys opened with terraced fields and almond orchards, herds of cattle and fat-tailed sheep. Some of the homes had trailing vines on their verandas. It could almost have been northern Italy. Narrow cultivated strips along the river valley gave way abruptly to steep, rocky mountains. The sun set over the Shibar Pass, yielding a glorious view over the lower mountains in the evening sun. It began to get cold – it was 10,000 feet after all. Bamiyan itself was reached in the pitch black and freezing cold. The hotel, once the governor’s palace, was a gaunt building perched on a spur over the valley.

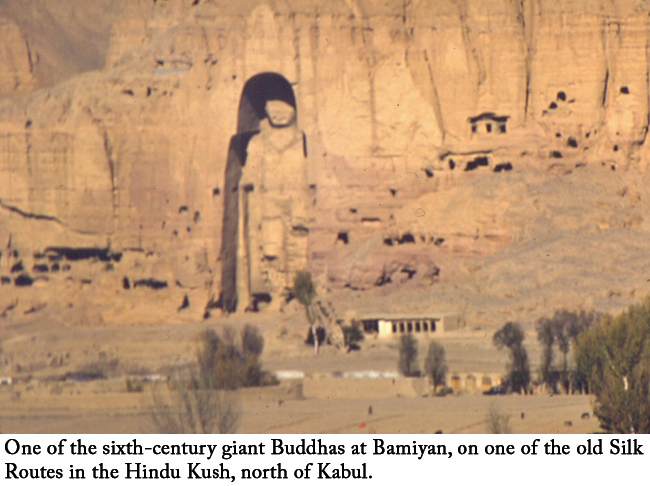

The next morning Nigel went to fetch water, and had a tough job breaking the ice from around the tap. The hotel window looked out on the two colossal Buddhas carved out of the sandstone cliffs across the valley. Almost 2,000 years ago merchants who travelled between China and India stopped there to rest before crossing the mountains. Monks lived and meditated there; they had left their traces in the caves that still honeycombed the area. It was they who built the great stone statues, the smaller one 120 feet high and the larger 175 feet. Bamiyan remained prosperous in spite of various wars until the time of Genghis Khan, 700 years before, when his grandson was killed in the valley. Thirsting for revenge, he ordered that every living being there, animal or human, should be killed.

In March 2001, more contemporary vandals would wreak their wanton violence as the Taliban, with their fervent, religious hatred of what to them was the ‘brazen image’ of offence to the Creator, fell upon this unique site and destroyed the Buddhas.

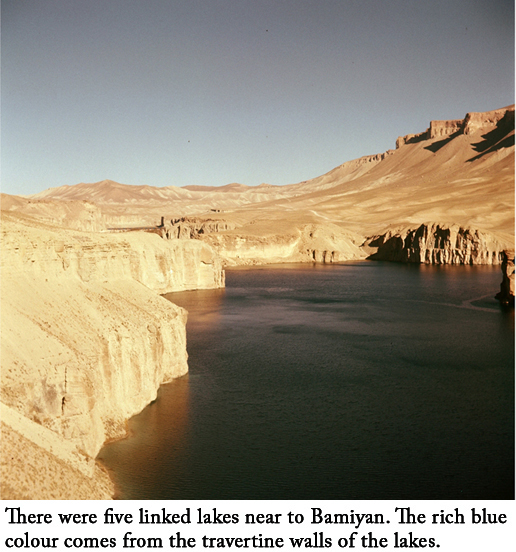

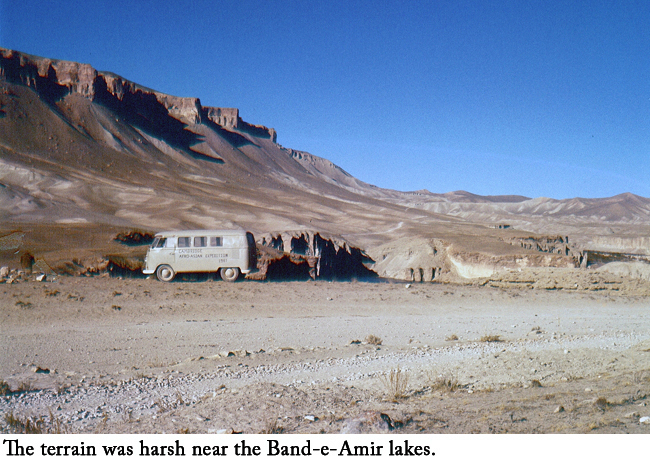

A few miles further the road dropped down through harsh terrain to the amazingly blue waters of Band-e-Amir. Its five lakes form a chain, separated from each other by natural dams. The water was so clear that one could see fish swimming 15 to 20 feet below the surface.

Two punctures punctuated the drive back to Kabul in the dark. Nigel and Tony pumped furiously every few miles to get to Kabul in the early hours of the morning. The engine ‘pinked’ badly from the low-grade Russian petrol, like little hammers knocking against the pistons. Before the Pakistan border was closed, high-grade American petrol was sold in Kabul. Now, with no tankers coming through Pakistan, the Russians were sending tankers down over the Hindu Kush.

The following day, lunchtime was drawing on, and heads were clearing after a wild party at Ron’s house. Suddenly, through the gateway of the Turkish Embassy appeared Mehmed, carrying his holdall and a basket full of grapes. After a much-needed shower and meal he told his story.