13

TO THE OXUS

How Mehmed Pushed His Luck

It was 23 October and Mehmed’s plane was soon climbing over the Salang Pass. With their primitive equipment, the old World War II DC3s always took this course, quite low near the peaks, giving the passengers an unrivalled view of the snow-covered tops of the Hindu Kush. Far below the Russians were building a phenomenal road with a three-mile tunnel right through the mountains. For nearly 15 minutes the plane plodded along, at times dangerously close to the icy tops. Then it descended gradually to land at Kunduz, a small town with a large cotton factory and an airport project. The Americans were going to build a control tower and a 2,000-foot-long tarmac runway. So far there was only a short, dusty patch with two Aryana – Afghanistan’s national airline – vehicles waiting at one end for the disembarking passengers. A barefoot child squatted, playing in the dust.

Dr Kardesh, the Turkish doctor in charge of the WHO anti-malarial campaign in Kunduz, was an old friend of Mehmed’s family, and his wife was an excellent cook. WHO headquarters were at the Cotton Company’s hospital, and their hostel served as a hotel for foreign travellers. Kunduz was important strategically. The road to the north led to the Soviet Union, only 40 miles away, and had only recently been completed with Russian financial and technical help. Once predominantly Uzbek, the population now seemed at least half-Afghan – that is, Pashtu-speaking people from the south, who had been resettled here. Kunduz was not exciting, but the Kardeshes seemed quite happy. ‘At least we have electricity and water,’ they said. ‘In many WHO malaria regions conditions are much worse.’

The Oxus, or as it is called locally, the Amu Darya, is the longest and by far the most important river in Central Asia. It stretches for 1,000 miles and constitutes a natural boundary between Afghanistan and the Soviet Union for about 400 miles. Foreigners were not even permitted to set eyes on it. Andrew Wilson (author of North From Kabul, which Expedition members had all read avidly before their departure) had written, ‘I watched for some sight of the Oxus – that elusive great river which gave its name to the country over which I travelled, but which every device of security had prevented me from seeing’. This presented Mehmed with a challenge, to which more flames were added when the Kardeshes told him of the strict security measures and the skill with which the Afghans kept all foreigners in their sight.

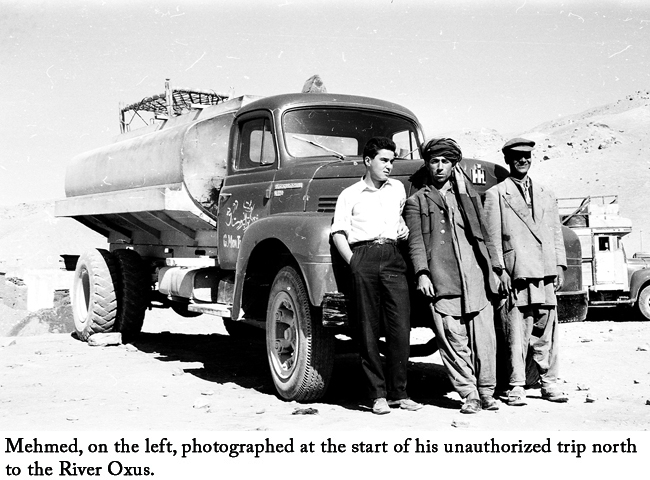

Mehmed learned that lorries to Kizil Kala, the border town in the Kataghan Province, left early in the mornings. So he told the hotel manager he would be getting up early to go to Khanabad, sister town of Kunduz, only 15 miles away, and home of the best bushkazi team. Dressing discreetly, he slipped out of the front door before dawn. The policeman who had been detailed to watch his every movement lay fast asleep on a chair in the foyer. The idea was that, as a Turk, and after all ‘Turks and Afghans are brothers’, the ‘mistake’ would be treated lightly, especially because of Dr Kardesh and the Turkish Ambassador in Kabul. About 100 yards up the road was an international licence-plated tanker with a non-Uzbek co-driver who was supervising the giriskar (‘grease monkey’), as a lowly mechanic was nicknamed. This was ideal, as Mehmed could thus speak in Farsi with an Afghan and so have a second ‘excuse’. Luckily, he spoke bad Farsi. ‘Bandar in half an hour!’ he shouted. ‘Bandar’ means frontier in Persian, and thus the fact that Kizil Kala was not mentioned was even more pleasing. Hoping that the giriskar would do his job quickly, Mehmed jumped into the lorry. Two policemen were standing around, so he looked the other way, quietly cursing under his breath. The giriskar and the co-driver then began to quarrel over new supplies of grease. The giriskar demanded more; the co-driver refused. Eventually the co-driver gave in, and 15 minutes later they were off. Fifteen minutes of wondering when they would catch up, for surely the officer in the hotel had woken up by now.

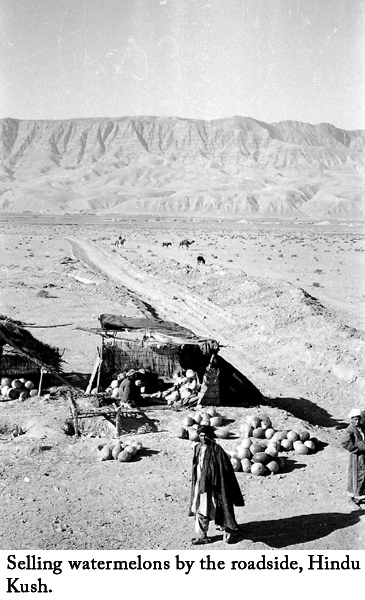

The road was good and looked fairly new. Suddenly, the fertile cotton fields stopped and gave way to a bleak, unrelieved wilderness which the Afghans call dasht. A vast, dead plain without skyline or horizon, in which nothing lived or moved but the smoking dust. After nearly two hours, the lorry topped a small hill and there below were the cotton-growing plains of the Oxus. In the background stood the big depots storing Russian petrol, and other buildings of Kizil Kala, and further still rows of hills. But where was that elusive river, the Oxus? The driver had not talked much the whole way, but alternated instead between bouts of song and pinches of naswar to keep himself going. The truck passed safely through the customs post.

Mehmed’s idea was just to look at the river and then give himself up to the chief of the frontier police. Everyone kept looking at him, so he hurried in the direction of the watchtower from where he hoped to see the Oxus. Two minutes later and there it was. There was no one around: absolute silence. All that could be heard was the gentle lapping of the water on the bank below. Across the snaking blue waters lay the USSR. Apart from a barbed-wire fence, and a site way over to the west where the Afghans were having a port built, there was nothing. A Russian ship steamed slowly upstream against the current as Mehmed unwillingly walked the ten yards into the compound of the frontier guards. The first part had been successful. What would happen now?

Mehmed, with one eye still on the river, asked to see the Komiser (chief). Bedlam broke loose in the camp as people woke up from their siestas. Finally the Komiser arrived, looking very puzzled. He was short and fat, looking more like a cook than a Komiser in his ill-fitting, dark brown uniform. After they had politely asked after each other’s health, Mehmed, smiling stupidly, explained in Farsi that he had got on the wrong lorry and arrived in Kizil Kala instead of Khanabad. Would the Komiser use his authority to get him away as soon as possible as he had no right to be there?

They began walking back together down the hill towards the shops and chaikhanes. There was a lorry pointing in the direction of Kunduz. The Komiser told the driver and his cleaner, both Uzbeks, to take Mehmed straight to the Komandan (chief of police) in Kunduz, and said farewell. But elation was to be short-lived. Just outside the city boundary at Kunduz the lorry was stopped by the pock-marked officer who had been left fast asleep in the hotel a few hours previously. He was furious, and said he had been waiting for two hours. The Komandan was run to earth in his shabby office, dressed in a smart uniform reminiscent of pre-war Italy. He was talking on the telephone to the Komandan of Baghlan, the provincial capital, about the captive upon whom it soon dawned that he was no longer the popular ‘Turkish brother’. They looked all prepared to take hell out on him, for it was quite a serious slip-up for a foreigner to have ‘lost’ his way to Kizil Kala.

The Komandan started questioning in Farsi. Mehmed pretended not to understand. The chief’s face became red with anger, and almost unable to speak, he sank back into his chair while an Uzbek translated what he had just said. The whole procedure was becoming a farce, everyone talking at once, and the Komandan talking on the telephone to Kizil Kala, haranguing the Komiser for his stupidity and demanding that the driver be found and locked up; then, more respectfully, to Baghlan, to keep the Komandan there informed of the latest happenings. Finally they decided to put some questions written in English which, in turn, would be translated by the hotel manager into Farsi.

Mehmed’s request to have Dr Kardesh as interpreter was granted, and the party moved across to the hotel. En route to see the Komandan he called on the governor, who said that if he had wanted to visit Kizil Kala he should have asked permission. As it was he had acted contrary to Afghan laws and so was subject to punishment. For the umpteenth time they asked, ‘Why didn’t you enquire from the police which road you should have taken for Khanabad?’ and ‘Why did you say you were going to Khanabad, and then go to Kizil Kala instead?’ Mehmed replied warily, ‘As soon as I found out my terrible mistake, I immediately gave myself up to the Komiser and urged him to get me transport out of town.’

This sort of procedure could have gone on for hours, but luckily Dr Kardesh arrived and told the police that his wife had prepared dinner for the three of them. The whole thing could be settled the following day. After a good night’s sleep, Mehmed woke to find that he had been ‘jailed’ in the hotel. Towards midday the pock-marked officer turned up with the chief clerk and the driver of the lorry to Kizil Kala who had spent the night in custody. ‘Why didn’t you ask the driver if he was going to Khanabad?’ the chief clerk asked. ‘I assumed that only buses and lorries for Khanabad would leave from that point,’ Mehmed replied. The chief clerk looked rather pleased with himself at this weak excuse and walked off.

After lunch Mehmed was packed off to Baghlan by the same lorry that had taken him to the Oxus. Accompanying him this time was a shoddily clad private acting as bodyguard, who kept a grip on Mehmed’s passport and a thick envelope containing all the questions and answers from the interrogation session in his grubby hand. A pistol, especially given him for the occasion, hung conspicuously down from his belt.

Three hours later they pulled up behind a Russian Jeep parked outside the Komandan’s office in Baghlan. ‘Is the Komandan in?’ shouted the private in an important manner. ‘No,’ said one of the sentries. An inquisitive crowd gathered to look at the ‘spy’. Seconds later the Komandan arrived. He smiled in a friendly fashion and read a letter from the Ministry of Education in Kabul that Mehmed handed him. ‘Where are you going?’ he asked. ‘Mazar,’ said Mehmed hopefully. ‘You can join the Komandan of Aibak who is going up there in the morning,’ he said and walked away. He paid no attention to the envelope which the bodyguard was hesitatingly pushing forward. Mehmed grabbed his passport from the puzzled private, picked up his holdall, and jumped in next to the Komandan of Aibak in his Russian Jeep.

None of the gauges worked. The water stood at 110 degrees centigrade, the petrol-tank read dry, and the current read 20 amperes. It was a miracle it kept going. The night was spent at the Baghlan sugar factory club. Dinner was a delicious plate of Afghan pilao and chicken, with fresh salad. Shir Mehmed, a friend of the Komandan, waited until everyone else had finished then grabbed the remaining plates and finished them off, washing it all down with a jug of water, followed by six apples and three very large slices of melon. It was still bitterly cold when they all left the next morning.

The narrow road twisted and turned back upon itself at times, and for the last few miles the Jeep crawled upwards in first gear. Ahead lay the plain of Aibak, dominated on one side by a solitary snow-covered peak, very reminiscent of Mount Ararat in eastern Turkey. After a fine lunch in Aibak, Mehmed left the Komandan and Shir Mehmed as he wanted to push on to Mazar. He had heard that there was to be a game of bushkazi the following afternoon.

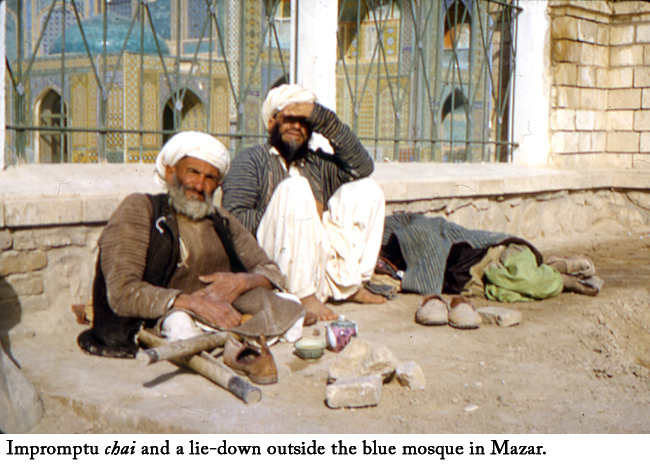

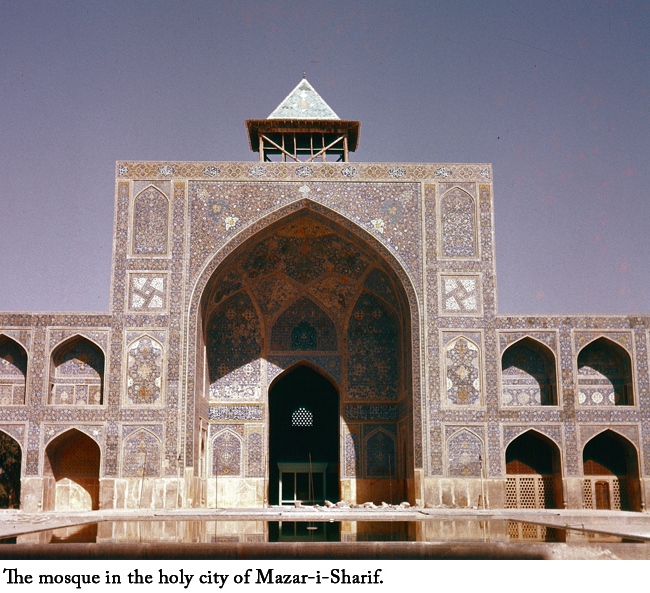

There was a tension and bleakness about Mazar which its proximity to the Soviet border did nothing to diminish. Its blue mosque and shrine, containing the relics of the Fourth Caliph of Islam, made it a holy city, which for generations had been a symbol of Muslim resistance to Russian encroachments from the north. Under the existing government it had become a centre of Russian technical and military aid operations. Three big highways came right down to the Afghan border on the Russian side, and the Russians were building roads in Afghanistan to link up with cities like Tashkent, Samarkand and Stalinabad (now reverted to Dushanbe, as part of Khrushchev’s de-Stalinization process late in 1961). How close Russia felt.

The game of bushkazi was cancelled as the ground was too hard. A game was going to be played with donkeys instead. It was hardly worth watching this prostituted version. A better option was to visit Balkh, the ‘Mother of Cities’ and birthplace of the Aryan civilization. Once it held the same status as Rome and rivalled Babylon in prominence.

Here he met a gentleman called Bahadur Khan, a name reminiscent of old Mogul lineage, a contact that Mehmed had been given in Kabul. Later in Mazar, Bahadur would tell how he and his family had got through the fence by the Oxus and crossed those icy waters on large pieces of wood back in the 1930s. They were some of the last refugees to escape from Soviet Turkestan. Now they hired a Russian Jeep and from the bazaar drove up a track into an enormous saucer of dust. These were not ‘ruins’ in the classical sense: no broken arches or towers or graves, just this great dust saucer surrounded by a continuous, jagged, crumbling wall. But Balkh was no disappointment. The Timurid mosque was covered with deep blue tiles, half on the dome, half scattered on the ground. All you had to do was pick yourself a specimen of these valuable tiles, dating back to the fifteenth century. Afghan restorers were hard at work with new and revolting colours, and slowly the dome was losing some of its shape.

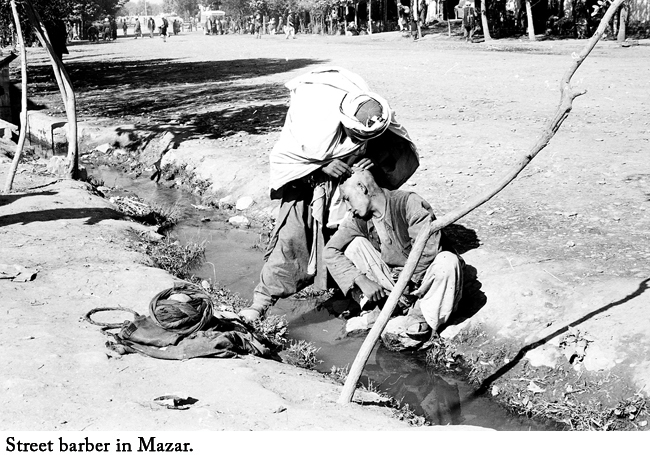

Back in Mazar, Bahadur Khan was a kind host. He was in the import-export business, and was the Pye Electrics agent in Afghanistan. His nephew, Lutfullah, a young Uzbek of 19, appointed himself guide and interpreter of Farsi. At a grand dinner, pilao was served. Two months earlier Mehmed and Nigel had had this delicious Uzbek national dish in Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan. There it was washed down with wine; here green tea had to suffice. In Tashkent talk ranged over world politics, nuclear physics, and economic ideologies; in Mazar, not so far away, the only topics of conversation were religion and the Expedition – even the street barber apparently had got to know about it. In Tashkent, everyone in the house had received higher education; in Mazar, none had gone beyond primary school.

Mehmed visited the new girls’ high school, and sat in on a lesson. ‘Do you speak English?’ he asked the young teacher from Kabul. ‘No,’ she said. Later she was introduced as the English teacher. She made the children read extracts from Aladdin’s Lamp. They paid scant respect to punctuation marks and had appalling pronunciation, a clear indication that they did not understand more than half of what they were reading. This the teacher later admitted. Asked if they understood the words, the teacher replied, ‘Not yet’.

Mehmed had reluctantly to leave Mazar sooner than expected. Instead of hiring a Jeep to Kabul, which would cost 300 Afghanis, he preferred the overloaded Chevrolet servis bus to Pul-i-Khumri. The only seat available on the bus was at the back by the door. You had to pull your feet right underneath the seat while people climbed in and out, otherwise they just trod on you. The seat was small; the door had no windows, so dust was blowing into his face. At the first petrol stop he decided to get up onto the roof and travel havakhurri (‘eating air’) as the Persians say. Clambering over people’s legs and shoulders, he pushed his way to the front to see better.

Afghan buses had sides built on the roof, about 50 centimetres high like a truck, to stop people from falling off, but at the front and back there was nothing. The seat was on top of the tool-box, a slightly precarious position, with nothing to hold on to. Sitting cross-legged, gripping the edges tightly with both hands, Mehmed prayed that the driver would not suddenly brake. From Mazar to Pul-i-Khumri his travelling companions were young Uzbeks and Turkmen on their way to do military training. They were a cheerful bunch, and welcomed Mehmed as a ‘brother’. Despite wearing three sweaters, two pairs of trousers, a pair of pyjamas and a sleeping bag, he nearly froze to death during that 17-hour drive. It was only the raucous singing of the friendly, ill-clad conscripts, and the occasional cup of tea and bowl of rice that enabled him to survive.

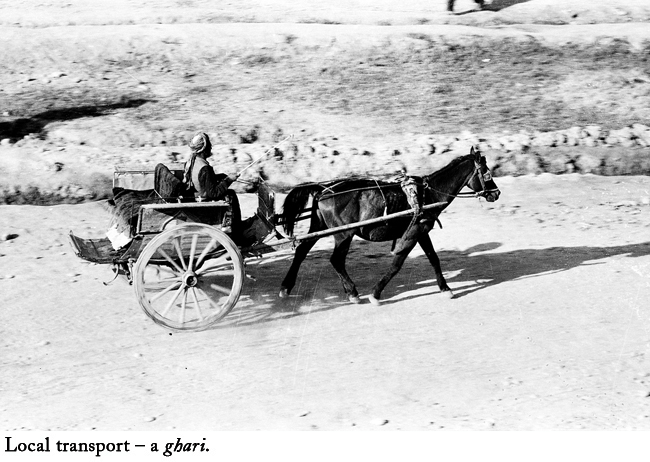

On reaching Pul-i-Khumri, Mehmed shook hands with his fellow passengers and caught a ghari to the Nassaji Club, the second-best hotel in Afghanistan. A sentry with a rifle and a tired-looking clerk made up the reception committee. Desperately tired, Mehmed ate all the eggs in stock, took a hot shower (ten Afghanis extra) and retired to bed to wake up 13 hours later. The club stood above the river, overlooking a terraced garden of roses and snap-dragons, illuminated at night by coloured lights. Pul-i-Khumri was decidedly the most pleasant place Mehmed had visited north of Kabul, excluding the architecturally interesting parts of Mazar and Balkh. The river ran through a narrow valley overlooked on both sides by mountains. The riverbanks were lined with trees in fine autumn colours.

The last few miles of the long journey back to Kabul were in relative luxury, on Russian paved roads, despite being on the top of a tanker. The smoothness of the surface helped Mehmed reflect on the last seven days. North of the Hindu Kush was an entirely different world, and an entirely different country – Turkestan. Everything was different, race, language, habits, culture. Artificial boundaries had been created and Turkestan was divided into four parts: Russian, Persian, Chinese and Afghan Turkic areas. Resettlement plans had changed the appearance of the parts. Just as Russian Turkestan was unmistakably Russian, Afghan Turkestan was so typically Afghan. With all the new road links with Russia, Mehmed wondered how much Russian influence would entrench itself in the northern provinces. The southern border with Pakistan was closed; the northern one was very active.

The noise of the traffic in Kabul rudely pulled Mehmed out of his reverie. Ambassador Benler was most relieved at Mehmed’s safe return, and he and his wife invited everyone in for drinks that evening to celebrate his release, and so Mehmed could tell his story.

Reunited, Tony, Nigel and Mehmed later drove into town for a last meal at the cafeteria, and were later joined by their student friend, Ali, who gave his views on the different ways different countries had of giving aid to Afghanistan. So much had been seen or heard of the American and Russian ‘approaches’ on this subject that it was good to hear an Afghan’s views. ‘It is true,’ he began, ‘that the total foreign currency value of Soviet aid is greater than that of the United States. It is also true that their projects have made a greater initial impact on our people than have those of the US.’ He paused. ‘But,’ he continued, ‘this is not necessarily going to be a long-term evaluation. In Russia itself, so I’m led to believe, they seem to stress quantity rather than quality in their work. But, I admit, the Russians score immediately on their kind of aid,’ he emphasized in a matter-of-fact tone of voice. ‘A silo, cement factories, arms, air-lifts, paved roads. While the Americans embark on more long-term policy projects which do not show so quickly: education, irrigation schemes such as in the Helmand Valley, and roads which are out of town! For Afghanistan neutrality is an attractive and well-paying way to draw economic and military aid from both “blocs”,’ he added with a quick grin.

Mehmed, meanwhile, wondered what had happened in Kabul so that, instead of having life made very unpleasant for him – apart from a few thumps – he had been given VIP treatment in Baghlan. Dr Kardesh, it appeared, had sent a cable in Turkish to Ambassador Benler; two words only: ‘Demirer nezarette’ (‘Demirer in custody’). At the very moment when he was being taken to Baghlan from Kunduz under arrest, four high-ranking Afghan Air Force officers were waiting for visas from the Turkish Embassy. Their plane was due to leave Kabul airport the same afternoon. Mr Benler, guessing that Mehmed must have done something stupid but nothing criminal, called the Afghan Foreign Ministry and told them, ‘Unless Demirer is released immediately and shown traditional Afghan hospitality, the visas will not be issued.’ That was how Mehmed’s luck had changed so dramatically in Baghlan.

Passing through Bamiyan on the last bit of his journey back, Mehmed had bought a basket full of beautiful grapes which he presented to Mrs Benler, who had a weak spot for him. Grapes or no grapes, Mr Benler first listened to Mehmed’s story and, after taking him aside to give him a telling-off, said, ‘Get out of Afghanistan as soon as possible ...’

They did.

The next day Mehmed, Nigel and Tony set off for the Khyber Pass. They had now completed the first stage of their Expedition, and had covered 13,000 miles.

*

During the afternoon of 13 January 1842, an exhausted man and horse rode up to the walls of Jalalabad. Dr William Brydon, ancestor of Bob’s wife, was the sole survivor of the British expeditionary column. Behind him lay 4,500 soldiers and 12,000 civilian camp followers who perished during seven days of non-stop ambush in the perilous defiles descending over the Khyber to the plains below.

Over a century had passed, and on 15 February 1989, General Boris Gromov, Soviet commander, was the last man to cross the Termez Bridge out of Afghanistan. Ten years of Soviet invasion were over at the cost of tens of thousands of Soviet and Afghan lives. Mujaheddin, clans and warlords, then the Taliban wreaked their own tolls on the country. Now a US-led coalition bitterly wonders how it was lured there in the first place and wriggles to get out. In 1961, a traveller could already sense the fragility of Afghanistan, caught up in the battle for influence between the West and Russia, pitched against the Pashtu people astride an artificial frontier line with a touchy Pakistan, beset with its own strains and contradictions. The failed non-state of Afghanistan remains a vital and volatile geopolitical turntable for regional security – or anarchy.

*

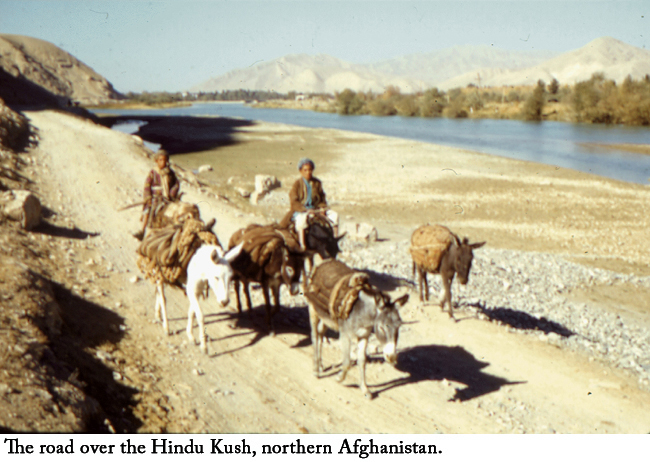

The number of Kuchis increased as the Kombi chugged closer to the border. Some of their womenfolk were striding barefoot down the road, weighed down with ornamental bands of silver coins around their gaily embroidered blouses, in brilliant flowing bloomers, and heavily braceleted on wrists and ankles. They were often beautiful and always unveiled. Donkeys and camels were loaded with pots and pans, children, squawking chickens, tent poles and the felt sides of tents. Dogs, like heavy, bristling wolves, loped alongside. The men in brightly coloured garments, all in tatters, rode gaily caparisoned horses, sat regally on camelback, or in less dignified fashion on the backs of donkeys, their legs outstretched so as not to touch the ground.

One hundred thousand or more Kuchis faced starvation along the border. As they had done each winter, these Kuchis were returning from their summer grazing grounds in Afghanistan towards the plains where they passed more than half the year. This time, however, they were stopped at the Pakistan border. They were asked for passports and visas and valid international health documents for themselves and their great herds of cattle – demands for things that meant nothing to them. So the bulk of them were now stranded on the border. There was nothing for them to return to, as their summer lands were under snow. In the high passes where they had been blocked, the nights were already freezing cold, and every day saw the snow line on the hills come lower, while their herds demolished the thin grass along the trail, and their own supplies for their interrupted march dwindled. The Kuchis were a warrior tribe, and when the choice became absolute they could not be expected to choose starvation rather than fight, although the fight had to be a losing one. Though the Kuchis migrated primarily for fodder for their herds, they turned their hands also to the hardest manual labour. Pakistan would feel their absence that year. Already in some districts the sugar cane stood late in the fields because the Kuchis were not there to cut it. Gunfire had broken out in one incident, and Kuchis had been killed. As the cold and their dying flocks made them increasingly desperate, many more such clashes threatened.

That night was spent at Jalalabad, a historic border town famous as a lush winter resort for royalty but often turbulent and contested by warring tribes. After a quick cold shower, punctuated by Nigel’s choice of oaths, the three left the modern, newly built Ningerhar Hotel and headed further out towards the border. Just before reaching the edge of the town, they visited the police station, having first gone to the Russian consulate by mistake. Their exit visas had expired the day before, so by rights they should have been out of the country by then. No one seemed to worry much. But it was better to drive through the Khyber Pass by daylight, hence the stop for the night at Jalalabad. The bazaar had an oriental atmosphere, heightened by the textile shops, rich with silk and imported rayon turban cloth, and owned by the Sikhs who for generations had made their homes there. The chaikhanes were vulgarly bright, with colour prints of saucy ladies from Delhi. The wireless blared music from Indian records. Beyond the last grocer’s shop, with its splash of red capsicums strung up to dry in the sun, the bazaar ended, and there was the inevitable open wasteland where houses had been demolished to make way for a projected New Town. The line of demolition hugged balconied mud houses, with lines of drying washing and an air of fiesta. Mehmed went off to see the Governor’s Secretary to see if he could be persuaded to help. Nigel and Tony sat drinking awful tea with the clean-shaven, stern-looking, but kindly chief-of-police.

Soon Mehmed returned – his visit to the big man had worked. Everything was apparently OK, everyone shook hands, piled into the Kombi and drove towards Pakistan as quickly as the Kombi would move, just in case anyone should change their mind; and this even after the chief-of-police had offered them lunch. A few kilometres before the actual border there was a passport check, but no one mentioned that the visas were out of date. The number of Kuchis encamped by the roadside had gradually increased as the border drew nearer, their black tents firmly dug into the ground, and their camels and donkeys cropping the sparse grass around the encampments. The Kuchis would certainly not have understood what all this trouble over visas and jabs was about. The Pakistanis were certainly going to miss their salt, timber and carpets, which the nomads normally sold before their long march back across the Hindu Kush.

The border was deserted and as silent as a graveyard, with empty lorries pulled up by the roadside. All the desks in the customs office were closed, except one. A thin layer of dust had formed on the woodwork, and an air of silence reigned throughout the whole building. No Afghan or Pakistani was allowed to cross, so all the bus services stopped here, ejecting their disgruntled passengers, who milled around the frontier-post, just to make sure the border really was closed. Only tourists and those people who travelled on diplomatic passports were allowed through. It took a while to persuade the customs officials that a carnet was not needed for the Kombi, before they dropped the heavy barrier chain. On 7 November, the Expedition slowly crossed the 100 yards of no man’s land into Pakistan.