Mario Batali and his business partner Joe Bastianich own fifteen restaurants across the country, including their flagship New York City restaurant, Babbo. He is the author of eight cookbooks and the host of television shows. He started the Mario Batali Foundation in May 2008 to feed, protect, educate, and empower children. Along with his wife and their two sons, he splits his time between New York City and northern Michigan.

If you ask my son Leo what his favorite thing to eat is, his flat-out response is, “Duck testicles.” He’s eleven, and in fact, I think he’s only eaten them maybe four times. But he was fascinated by the idea that we were eating duck testicles. Benno, my thirteen-year-old, says his favorite thing is pasta, but Leo says duck testicles. He may say it for the shock value and the provocation, but he knows how he likes them: in a dish called cibreo, which is made with all of what they call “the gifts of a chicken.” It has the cockscomb, the wattle, unborn eggs, gizzards, kidneys, and, of course, the testicles.

I have dinner with my family every night, no matter what I’m doing at work, unless I’m not in town. Maybe I won’t eat because I’m going out somewhere later on, but I sit down with my wife and sons, and I’ll have a little bit of salad or something. We always sit down and talk every night. And that is a crucial component. It’s not necessarily the food that’s the most important thing: it’s the family time, the undirected family time with no computer, no TV, no text messages, no phone. Nothing is allowed during dinner.

When I was growing up—I must have been about eleven—my mom went back to work and my ten-year-old brother, eight-year-old sister, and I started helping out around the kitchen. We each cooked dinner once a week for five people. We could do anything we wanted, but we had to do it. It could have been as easy as buying frozen Banquet fried chicken, or a TV dinner, and just heating it up. We got involved, making soup and interesting kinds of stews. It was our little job. We had dinner every night at six o’clock. There was no concept that we might not have dinner together. No matter how busy you were, you had to sit down. That was it.

When our kids were born, my wife and I didn’t really cook much. We took them to the restaurants. A common myth among young parents is that their babies are very breakable in the first two years. In fact, it’s the opposite. That’s when you have freedom. It’s almost the end of it. So take them with you. In three years it’s going to be a different thing. We took them to the restaurants all the time, because we wanted everyone to see them. We wanted the kids to feel comfortable in the restaurant environment.

When they reached five or six, we started to do a little more cooking. There were big issues. My kids would eat anything green, but nothing with flecks of green, like parsley or chives or scallions, or anything that I find delicious. I found that the easiest way to get kids to try something new is to have the child assist in the production. Because once they’re invested and have actually made it—even something that they don’t, or might not normally, eat—if you get them to make it with you, by the time you’re done, they feel like they have to eat it. Not because you’re telling them to do so, but because they’re interested. They’ve been playing all along. They’re not grossed out by it suddenly.

The first problem for our guys was pesto. I remember thinking that pesto was the greatest thing in the world, and they thought it was the most disgusting thing, until we cleaned a whole bunch of basil, put it in the blender with a little olive oil, garlic, pine nuts. We made it together, and we’ve been eating it ever since.

Another great way to keep children involved in food and keep it from becoming weird or a stigma is to watch how you introduce new things. Anytime you have a new ingredient, don’t talk it up. Just put it on the table. Here it is. “What is that?” “Those are cardoons.” “Oh, great, I love them.” Don’t make like, “Today we’re going to try cardoons, everybody. Let’s get worried.”

A cardoon, by the way, is a member of the thistle family, Cynara cardunculus, a vague cousin of the artichoke. It looks like a big, tall, silvery celery. And it kind of looks like an artichoke plant. You peel it and then you blanch it. And then you can sauté it. My grandpa used to bread them in crumbs and fry them. I really like them after you blanch them the first time, put them in a gratin dish with a little béchamel and a little fontina, and bake it. Man, they are good. Cardoon gratinato for supper on a Tuesday night.

My wife never makes anything, because when we come home from the grocery store, by the time the groceries are out of the bag, I’m halfway done making dinner.

When I’m cooking at home, I don’t deliberately turn it down or turn it up. If I’m making fish, I don’t generally put a sauce on it. I have a little extra really nice balsamic vinegar and we drizzle it on. So it’s tuned up, but only to the level that the ingredients require. It doesn’t take a lot of technique to extract that intensity. Like when you cook fish, if you cook it 80 percent on the first side and then just turn it over and then take it out of the pan, it gets that really nice caramelized crust—and it’s delicious. But most people don’t know that because they see it on TV, and they want to move it around. Like you put a scallop in a pan and you don’t move it, it gets perfect. But if you move it around, all the liquid comes out and it poaches it.

Both the boys love monkfish liver. We treat it like foie gras, just sauté it really quickly. We had tripe a couple of days ago. I did it two ways because it was a challenge. The smooshy part is challenging. If you blanch it twice with a little bit of vinegar and a touch of vanilla in the second blanching liquid, by the time it comes out it tastes a little less uric and a little bit more like clean meat. Then we slice it quite thin and serve it in a salad. In my family, if you dress something properly with really good extra-virgin olive oil and a nice, bright acidic vinegar, a little salt and pepper, and maybe some shaved onions or scallions, just about anything could taste good.

Every day I do breakfast. Often we’ll have what we call a Batali McMuffin, which is a whole wheat English muffin with a greenmarket egg, a slice of ham, and cheese. The other morning, because it was white truffle season, we had scrambled eggs, bacon, and white truffles. A lot of times we’ll do egg tacos. Once every seven or ten days we’ll have crepes. Generally I make them with chestnut flour. And we put ricotta or jam on, or both, or just cinnamon and sugar. Breakfast is pretty simple and straightforward.

For dinner, at least once a week I will always make just sautéed fish. I’ll go to Citarella and pick up the protein of choice that day, which is anything from grouper to wild salmon. It’s always sustainable. It’s generally line caught. It’s always at least twenty dollars a pound. It’s expensive over there, but it is remarkably good. We’ll just sauté it in a nonstick pan or put it under the broiler with a little glaze of some kind and serve it with our family’s chopped salad, which is romaine, shredded carrots, pitted olives, feta cheese, and red wine vinaigrette.

But when it comes to food, you don’t have to spend a lot to instill good values. Take pickling and canning. You go to the greenmarket, you pick up five or ten pounds of cucumbers. You come home, you talk about them, you prep them, you get all the brine ready. You follow the instructions in the book. You get the Mason or the Ball jar. You put it all together. And in six weeks you have something that says something about your point of view. And the kids love to get involved with that; they love to participate in it. It’s a project, but it’s an afternoon for a couple of hours.

Doing something like that once a month, whether making strawberry jam or pickles, or an antipasto, or any kind of little pickled acidic thing—that in itself speaks volumes about a family’s potential. When you can do that together with your kids as a project, that puts them in the kitchen during leisure time, which makes the kitchen less a weird place, or a sacred place, or an odd place. It makes it more of a social place. All of the places that I live, particularly my house in Michigan, our entire world is the kitchen. We do our homework on the kitchen counter. Everything is in the kitchen, so we’re always there—that’s where we live.

And when dads realize how quickly they can make their whole family really happy after an hour of work at the max, they’ll want to do it. The best reason to cook, besides its being delicious and good for you, is that it will automatically make you look good. You’ll look like a hero every day.

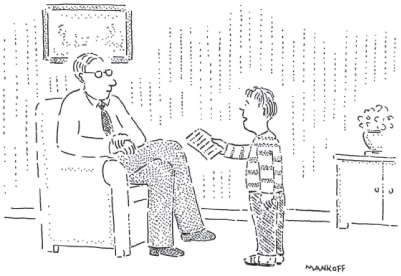

“Dad, here’s that update on my childhood you requested.”

Serves 6

This recipe is courtesy of Molto Gusto.

Kosher salt

¼ cup coarsely ground black pepper

6 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

6 tablespoons unsalted butter

1 pound dried linguine

¼ cup freshly grated Parmigiano-Reggiano, plus extra for serving

¼ cup grated Pecorino Romano

Bring 6 quarts of water to a boil in a large pot and add 3 tablespoons kosher salt.

Meanwhile, set another large pot over medium heat, add the pepper, and toast, stirring, until fragrant, about 20 seconds. Add the oil and butter and stir occasionally until the butter has melted. Remove from the heat.

Drop the pasta into boiling water and cook until just al dente. Drain, reserving about ½ cup of the pasta water.

Add ¼ cup of the reserved pasta water to the oil and butter mixture, then add the pasta and stir and toss over medium heat until the pasta is well coated. Stir in the cheeses (add a splash or two more of the reserved pasta water if necessary to loosen the sauce) and serve immediately, with additional grated Parmigiano on the side.

Serves 4

This recipe is from The Babbo Cookbook.

¾ pound guanciale or pancetta, thinly sliced

3 garlic cloves

1 red onion, halved and sliced ½ inch thick

1½ teaspoons hot red pepper flakes

Kosher salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste

1½ cups basic tomato sauce

1 pound bucatini

1 bunch of flat-leaf parsley, leaves only

Pecorino Romano, for grating

Bring 6 quarts of water to a boil and add 2 tablespoons of salt.

Place the guanciale slices in a 12- to 14-inch sauté pan in a single layer and cook over medium-low heat until most of the fat has been rendered from the meat, turning occasionally. Remove the meat to a plate lined with paper towels and discard half the fat, leaving enough to coat the garlic, onion, and red pepper flakes. Return the guanciale to the pan with the vegetables and cook over medium-high heat for 5 minutes, or until the onions, garlic, and guanciale are light golden brown. Season with salt and pepper, add the tomato sauce, reduce the heat, and simmer for 10 minutes.

Cook the bucatini in the boiling water according to the package directions, until al dente. Drain the pasta and add it to the simmering sauce. Add the parsley leaves, increase the heat to high, and toss to coat. Divide the pasta among four warmed pasta bowls. Top with freshly grated Pecorino cheese and serve immediately.

The Splendid Table, Lynne Rossetto Kasper.

Just Before Dark, Jim Harrison.

An Omelette and a Glass of Wine, Elizabeth David.

And anything and everything by Paula Wolfert.