Peter Kaminsky has written many books about food and cooking, including Pig Perfect: Encounters with Remarkable Swine and Some Great Ways to Cook Them and Seven Fires: Grilling the Argentine Way (with Francis Mallmann). He was the managing editor of National Lampoon in the late seventies. His forthcoming book, Culinary Intelligence, will be published by Knopf in 2011.

I did not come from a religious home, unless you count Mark Twain’s Letters from the Earth as a sacred text. The concept of sin—original or otherwise—was not part of my upbringing. The exception was any form of racial prejudice. Use of the N word (for African Americans), the W word (for those of Italian background), the M word (for Irishmen), or the C word, (for any Asian, Chinese or not) was the surest way to earn a parental rebuke, if not an outright smack.

We Kaminskys prided ourselves on being free of the taint of racism. It was only after the birth of our first daughter, Lucy, that there awakened a deep-seated and unshakable prejudice in my soul. Of all the kinds of people on the earth, it became clear to me, there was one group that I simply could not abide: two year olds.

Having but recently mastered the art of walking upright and the rudimentary use of language, they are the most uncontrollable, willful, demanding creatures imaginable. “No” is their favorite word; instant gratification, their inalienable right.

Such was the case with young Lucy Kaminsky one February morning in 1988. My wife, Melinda, is a woman of great patience (which you have to be if, like her, you are a second-grade teacher), but she was fed up with Lucy, who had just hurled her scrambled eggs on the floor and was wailing like a mourner at a Bedouin funeral.

“I will never have another child,” Mel vowed (this was two years before the birth of daughter number two, Lily).

Like generations of concerned fathers before me, my helpful response to this crisis was to grab my coat and leave.

“I’m going to see the Russians,” I said, referring to the Saturday market at the smoked-fish factory in Red Hook. Once a week, a local wholesaler, Gold Star Smoked Fish, opened its warehouse to the public and set out boxes of smoked salmon, whitefish, carp, mackerel, and the oily and redolent kapchanka. I never did get a positive ID on it, which probably doesn’t matter, since to my knowledge no non-Russian ever eats it more than once. Gold Star’s employees, mostly recent émigrés from Russia, had not yet adjusted to life in the land of plenty. According to the custom of Soviet-era peddlers, they took any selling opportunity as a chance to unload everything in their possession that might find a buyer. So in addition to smoked fish, you could also buy car batteries, wooden hangers, Polish chocolates, Hungarian jam, pocket calculators, and knockoffs of the polyester tracksuits worn by Russian Olympians.

But on that particular morning, what caught my eye was a hand-lettered sign. CAVIAR, it proclaimed, in an unsteady marriage of the Cyrillic and roman alphabets. Melinda loves caviar. I took the chance that here, on offer, was fine Caspian sevruga that some Russian sailor had waltzed off a cargo ship. I think twenty dollars got me four ounces.

I returned home as an unrepentant Lucy dumped all of her toys on the living room floor. I was relieved to find that the jackhammer I thought was tearing up my apartment was only Lucy beating an aluminum potlid with a wooden spoon.

“Ooh, look, Lucy, caviar!” I said, as if I had just presented her with a special birthday present, hoping that my tone of voice would change her mood.

Melinda, joyful at the prospect of her favorite food, tuned out our child’s cacophony and popped some thin slices of white bread in the toaster.

The demon-in-training must have wondered, What could possibly have distracted Mom and Dad from a well-orchestrated temper tantrum? She put down her potlid in midclang and approached the fish eggs.

“Here, Lucy,” her mom said, happy at the drop in decibels. Lucy tasted, tentatively at first, and then with such gusto that all thoughts of caviar on toast went by the boards as mother and daughter went spoon-to-spoon in a race to devour a whole generation of sturgeon.

And so, a gourmet was born: Lucy, an adventuresome eater from the get-go and a lifelong helper in the kitchen. She’d eat anything, like the risotto I made for her eleventh birthday, showered with a shaved white truffle as pungent as gym socks. Or the plump mopane worms—big as jumbo shrimp—that Matabele tribesmen offered us at a campfire in Zimbabwe, or the purloined ortolans that the chef at the Waldorf brought to our house one Sunday afternoon.

Some families have a mantelpiece crammed with framed photos of European vacations, horseback-riding exploits, graduations, beachy afternoons. My mantel is mental. My snapshots, like that of Lucy’s introduction to caviar, are often memories of family meals (or of fishing, but that, too, often ended in meals): shopping for them, preparing them, eating them. Next to Lucy in the family display is a photo of a picky eater, a pretty strawberry blonde child with a big smile, her younger sister, Lily.

Lucy may have been game to try everything, but the problem that presented itself with Lily was more often, would she eat anything? Or to make that question more accurate, would she eat anything apart from scrambled eggs, macaroni and cheese, and cheeseburgers? This wasn’t all bad. When I became a father, I rediscovered that macaroni and cheese—which I had not eaten for twenty years or more—is one of food-dom’s most satisfying pleasures, and a skillfully doled-out child’s helping of it always produces a few leftover bites for the cook-parent. As for burgers, had Lily not ordered one, I might never have tried the supernal one made at Union Square Cafe, where I ate at least three times a week all through the late eighties and early nineties.

The situation was not cut-and-dried; Lily would, on occasion, indulge in things besides the Holy Trinity of eggs, mac and cheese, and burgers. When we ate at restaurants, particularly ones with French words on the menu, she was intrepid. Daniel Boulud’s frog’s legs delighted her. Sottha Kuhn’s oysters with lemongrass cream at Le Cirque were slurped up with brio. Likewise, Francis Mallmann’s crispy sweet-breads (in this case we emphasized the descriptors “sweet” and “bread” rather than the more off-putting “grilled calf thymus”). Then there was all the weird and wonderful food in Oaxaca, Mexico, where we spent a month one summer. Although, come to think of it, Lily’s willingness to try new foods in Mexico may have been explained, in part, by the two sips of margarita that we offered her every evening as we sat on the zocalo listening to marimba bands. I think my former colleague at National Lampoon, the playwright John Weidman, had it right when he mused that many tests of will between mother and child could be resolved by serving the kid a stiff after-school martini.

I took Lily’s growing list of food dislikes as a personal challenge. Every parent wants his or her child to eat happily. When you are a food writer and a cook, this is doubly true. I treated every shopping trip as a game of chess, thinking five steps ahead to the finished meal. Relying mostly on hope and my recollections of Lily’s preferences, I could force a culinary checkmate—a plateful of things that she would have no choice but to polish off gratefully and with gusto. I knew she liked potatoes, so even though I have always been indifferent to them, I often bought a few as a way to soften her up. Then it was on to the main ingredient. For example, I once brought home some beautiful lamb chops. A no-brainer, I thought, because I recalled that on July 11, 1994, she wolfed down the rack of lamb at the first dinner ever served at Gramercy Tavern (the week that my eight-thousand-word making-of-the-restaurant story was the cover piece for New York magazine). I made the lamb, with a side of the aforementioned potatoes. Lily pushed it aside. “I’ll have scrambled eggs,” she advised.

“But Lily, you loved lamb at Gramercy Tavern,” I said.

“Yeah, but I don’t like it anymore. You know I haven’t liked it for six months,” she accused.

Then there was the Salmon Saga, Parts 1 and 2 (which bookended the I Won’t Eat Meat Because the Fat Makes Me Want to Throw Up Saga). It started when I made scrumptious oven-roasted wild salmon fillets, finished with olive oil, flaky salt, ground cardamom, and nutmeg with a chiffonade of basil, mint, and parsley. This was the first recipe in my first cookbook, The Elements of Taste (with Gray Kunz). The dish has never failed to please. Except this once.

“I don’t like salmon anymore,” Lily said, defaulting to, “I’ll scramble some eggs,” which was the one recipe she had mastered by age eight.

Did I mention that chicken was fine? It was, as long as it was crispy. Pan-roasted chicken breasts, finished in the oven and deglazed with vermouth, shallots, and honey passed muster with Lily. So that went into the rotation for a year or two until it began to bore me and I could no longer bring myself to make it ever again. The ability to fulfill an order even when you have lost all enthusiasm is what marks professional chefs from the home cook—even semifamous, cookbook-writing, stay-at-home dads.

Red meat did not become a viable option until we went to Argentina one Easter. At a remote cabin in Patagonia—in fact, the only structure on a lake at the end of a hundred miles of dirt road—the menu was meat, more meat, and the occasional wild brook trout. Lily was twelve, a time of many changes in a girl’s life. Her food rules evolved, and meat was back on the menu.

I could make steaks and smoked pork shoulder and spicy long-cooked spareribs: however, rather than capitulate completely, Lily advised that I hold off on the lamb for a bit. And the delicious pink-fleshed brook trout of Patagonia notwithstanding, Salmo salar was still verboten in Brooklyn. Then, last year, as part of a Bard College program, Lily took a road trip to New Orleans, where she worked as a volunteer at a day camp for inner-city kids. On the way there, she and her Bard posse stopped at Frank Stitt’s restaurant, Bottega, in Birmingham, Alabama. I knew Frank to be just about the most gentlemanly fellow on the face of the earth, and I had called ahead to tell him that my daughter and her schoolmates would be passing through.

As expected, he showered them with hospitality and made the road-weary young women feel special, so special that Lily ordered roast salmon with orzo and fresh herbs. Upon her return from New Orleans, she requested that I make Frank Stitt’s salmon.

Salmon? Lily? I could hardly believe my ears!

I grilled the salmon on our roof deck on the twenty-eighth of July. I would remember the date even if it were not Lily’s birthday: it’s the day she became an eater after my own heart. As the sun descended behind the Statue of Liberty, the reflection of its pale fire shimmered on the waters of the Upper Bay. For me it was surely a moment of warm contentment: Lily, her friends filling the air with the tinkling palaver of teenage girls, Lucy sitting on the lap of her boyfriend, lost in the moment, Melinda and I drinking rosé wine and feeling happily full of summer, sunset, and joy in our daughters.

Lily asked for seconds.

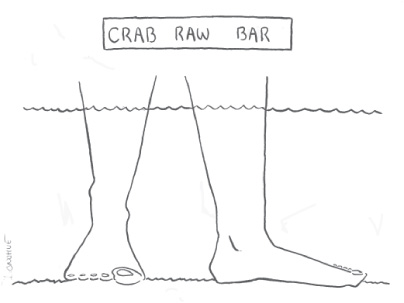

This is a recipe that we did for Seven Fires: Grilling the Argentine Way, which I wrote with South America’s greatest chef, Francis Mallmann. Every year I try to get Danny Meyer’s Big Apple Barbecue Block Party to let us do it on the streets of Manhattan with all the safety precautions FDNY could want. So far, no luck with the firemen, although Danny, as ever, is game. Please write the mayor and tell him, “We want our cow!” It gave me ineffable joy to write the list of ingredients and recipe as follows.

1 medium cow, about 1,400 pounds, skin removed and butterflied

1 gallon salmuera (salted water)

1 gallon chimichurri (see below)

Equipment and other supplies:

1 heavy-duty block and tackle attached to a steel stanchion, set in concrete

1 2-sided truss made of heavy-duty steel

16 square yards corrugated steel (4 × 4 feet)

1 heavy-duty pliers

2 cords hardwood logs

7:00 p.m.: Start fire, about twenty logs.

8:00 p.m.: With the aid of 8 strong helpers, put the cow in the truss, season with salmuera, and raise to a 45-degree angle with the bone side facing the fire.

Place corrugated steel over the skin side to reflect and contain the heat (just as you would tent a turkey).

Shovel coals from the fire under the cow so that the whole cow receives even, slow heat.

10:00 p.m.: Season the meat with salmuera. Continue to add logs to the bonfire and coals to the cooking fire all through the night.

Drink wine, sip maté, have coffee all night long. Take turns with other members of the crew, some sleeping and one tending the fire. You might roast a lamb to feed your crew all through the night.

10:00 a.m.: Remove the corrugated reflector, season the cow with salmuera, turn the cow and season that side with salmuera, too. Continue to cook, crisping the top of the cow.

2:00 p.m.: Begin to carve (some pieces may require longer cooking). Serve with chimichurri.

Yield: 2 cups

1 cup water

1 tablespoon coarse salt

1 head of garlic, peeled

1 cup packed flat-leaf parsley

1 cup fresh oregano leaves

2 teaspoons crushed red chili flakes

¼ cup red wine vinegar

½ cup extra-virgin olive oil

Bring the water to a boil in a small saucepan. Add the salt and stir until the salt dissolves. Remove from the heat and allow to cool.

Mince the garlic very fine and place in a bowl. Mince the parsley and oregano and add to the garlic with the chili flakes. Whisk in the red wine vinegar and then the olive oil. Whisk in the salted water and transfer to a jar with a tight lid. Keep in the refrigerator.

Note: Chimichurri is best prepared one or more days in advance so that the flavors have a chance to blend.

A Moveable Feast, Ernest Hemingway. Or almost anything by Hemingway. When he put food on a page, his words came alive. They jump out at you like your own name.

The Leopard, Giuseppe di Lampedusa. When the Prince cuts into the maccheroni at the Sunday dinner in the beginning of this novel, I can see the steam rise before me and I believe I can even smell the melted cheese.

Between Meals, A. J. Liebling. Liebling never wrote a bad word, and nothing ever made me want to be in Paris more than this book.

The Joy of Cooking, Irma Rombauer. I love the stories, especially the one under “About Lobsters,” in the original Bobbs-Merrill edition:

The uninitiated are sometimes balked by the intractable appearance of a lobster at table. They may take comfort from the little cannibal who, threading his way through the jungle one day at his mother’s side, saw a strange object flying overhead. “Ma, what’s that?” he quavered. “Don’t worry, sonny,” said Ma. “It’s an airplane. Airplanes are pretty much like lobsters. There’s an awful lot you have to throw away, but the insides are delicious.”

I have also always preferred Rombauer’s action method of recipe writing, but no editor I have ever worked for would go for it.

Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Julia Child. Not mentioning her is like talking about baseball and leaving out Babe Ruth. What Irma Rombauer started in me, Julia pushed across the finish line. The most bulletproof recipes ever written.

Le erbe aromatiche in cucina, Renzo Menesini. I can recite from it, but I’ll be damned if I can find it in the English translation; he once told me that the pomegranate seeds in chicken breast with bechamel looked “like drops of blood on the white belly of an odalisque.” Now that’s what I call a great headnote!

Henry Schenck, a professor of mathematics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, is the forty-seven-year-old father of three children under the age of ten. His wife, Maureen McMichael, is a veterinary specialist in small-animal emergency medicine and critical care at the university, and a vegetarian. Schenck, a meat eater, does more than 80 percent of the cooking for the family, which does not eat meat.

Once, when I was learning to make pesto, which I make with a mix of spinach and basil, I had trouble with the greens, which were sitting up above the blade of the blender. I hadn’t added the olive oil, and I thought I could tamp them down with a wooden spoon. I tried this, of course turning off the blender first. But then they immediately went back to the top. And then I tamped them down again, and they went back up to the top. I decided to tamp them down while the blender was running. It turns out, it’s rather hard to estimate how close the wooden spoon can get to those swirling blades. The wooden spoon hit the swirling blades, and I learned that pesto can become a projectile. It hit the ceiling, and the chunk of the wooden spoon that surrendered to the blades fragmented. The pesto had a bit of a woody taste. Usually you hear “woody” associated with a red wine, but this was woody pesto. I tried to pass it off as a “chunky, oaky” new version, but my wife soon put together the big green splotch on the ceiling of the kitchen with the woody taste in the pesto. My advice: turn off the blender before putting in the wooden spoon.

My kids are not very excited about cooking right now, which is interesting because usually kids like to be involved in activities that their parents model. This is OK for now because involving kids in anything makes it more time consuming. I’m often in a hurry. I move very, very, very fast. I drink a lot of caffeine. I’m currently working to see if it is possible to inject espresso directly into a vein. More often I just go for a triple espresso instead of a double. At some point, though, it will make sense for me to involve the kids in the cooking, just for their own growth.

Anytime that it’s warm enough to grill, which for us means April to November, I will marinate a whole salmon and grill it. Then I like to make a big garden salad, with a dressing of olive oil, lemon, and salt. I’ll serve it with a bowl of pasta with some sort of sauce, typically something easy like a pesto, and then a side of some kind of vegetables. One of my favorite things to do with the grill is to marinate some zucchini and grill it. If you slice them lengthwise, they grill up very nicely. This is an easy meal. Since I’m grilling, there’s not so much cleanup to do. It’s healthy and really quite good and it’s one of our standard dishes for guests because they always like it quite a bit.

In my youth, I encountered overcooked broccoli with some regularity, and it traumatized me so much that I could not eat broccoli for the next twenty years. I make a great broccoli rabe. You want to start with a nice, bushy green. When rabe is starting to go bad, the leaves start to get trimmed, and it becomes a tighter bunch. A nice, fresh rabe will have a bunch of leaves. As with any green, you should look for something that has good color and a nice appearance. Once you have your rabe, it’s really quite simple to prepare. Rinse it, chop off the bases of the stem, much as you would for regular broccoli. The bottoms tend to be tough. Some people like them, some people don’t. Take the big bunch in your hand and chop it into one-and-a-half-inch segments. One of my general rules is that anything with enough garlic is delicious. Sauté garlic in olive oil and then toss the rabe in. Add just a little bit of water to create a steaming effect. Stir it for maybe five to ten minutes, just like a stir-fry, then pull out a piece and test it. Don’t let it become soggy and mushy. Not many people like broccoli that is overcooked.

One of the best reasons to cook is that if you’re going to go out to dinner and spend a lot of money and a lot of time, and you have high culinary expectations, you’ll almost certainly be disappointed. Either the time or the money or the dish will not be worth it. So it makes a lot more sense to cook for yourself because then you won’t be disappointed. Anyone who enjoys cooking develops a sense of what will work. When there’s time, which oftentimes is not when you have kids, but sometimes, you can create your own fantasy meal. My fantasy meal is not about the ingredients. It’s about the prep and the cleanup. Having the prep and the cleanup done for me, that’s my fantasy.

1 medium-size head of basil

An equal amount of spinach

½ cup nuts (Pine nuts are popular, although walnuts work equally well. I’ve also used pecans or almonds, which result in a slightly sweeter pesto.)

½ cup olive oil

Rinse and wash the greens well.

Place them in a food processor or blender. (If the stems of the basil are tender, they can be tossed in also; late in the season, stems are often woody and should be discarded.)

Add the nuts and oil and blend for about twenty seconds.

Note: Most recipes call for adding ½ cup of Parmesan, but I think it works fine without it. This is also true for adding a clove of crushed garlic. Add salt to taste. Most important part: after blending, taste and add what you think it needs! For a creamier pesto, add more nuts and/or olive oil and blend longer.

Crusty bread, sliced

2 large tomatoes, diced

½ cup olive oil

1 to 2 cloves garlic, crushed

Salt to taste

Toast the bread in the oven until slightly browned.

Combine the tomatoes, oil, garlic, and salt.

Drizzle the mixture over the bread once it is toasted.

Olive oil

2 large heads of broccoli rabe, washed and diced

1 head of garlic, chopped

Lemon juice and salt to taste

Sauté the garlic in a little oil in a large pan.

Add the rabe and cook until the stems are tender (usually about 5 to 10 minutes—pull one out and take a bite to see how they are doing).

Add salt and lemon juice to taste.

Note: This is traditionally served as a side, but it is great over pasta (fettuccine works well). For an added twist, sauté a few diced porto-bello mushrooms and add them to the rabe.