The names of the Presidents change; that of Disney remains. Forty-six years after the birth of Mickey Mouse, eight years after the death of his master, Disney’s may be the most widely known North American name in the world. He is, arguably, the century’s most important figure in bourgeois popular culture. He has done more than any single person to disseminate around the world certain myths upon which that culture has thrived, notably that of an “innocence” supposedly universal, beyond place, beyond time—and beyond criticism.

The myth of U.S. political “innocence” is at last being dismantled, and the reality which it masks lies in significant areas exposed to public view. But the Great American Dream of cultural innocence still holds a global imagination in thrall. The first major breach into the Disney of this dream was made by Richard Schickel’s The Disney Version: The Life, Times, and Commerce of Walt Disney (1968). But even this analysis, penetrating and caustic as it is, in many respects remains prey to the illusion that Disney productions, even at their worst, are somehow redeemed by the fact that, made in “innocent fun,” they are socially harmless.

Disney is no mean conjuror, and it has taken the eye of a Dorfman and Mattelart to expose the magician’s sleight of hand, to reveal the scowl of capitalist ideology behind the laughing mask, the iron fist beneath the Mouse’s glove. The value of their work lies in the light it throws not so much upon a particular group of comics, or even a particular cultural entrepreneur, but on the way in which capitalist and imperialist values are supported by its culture. And the very simplicity of the comic has enabled the authors to make simply visible a very complicated process.

While many cultural critics in the United States bridle at the magician’s unctuous patter, and shrink from his bland fakery, they fail to recognize just what he is faking, and the extent to which it is not just things, but people he manipulates. It is not merely animatronic robots that he molds, but human beings as well. Unfortunately, the army of media critics have focused over the past decades principally on the “sex-and-violence” films, “horror comics” and the peculiar inanities of the TV comedy, as the great bludgeons of the popular sensibility. If important sectors of the intelligentsia in the U.S. have been lulled into silent complicity with Disney, it can only be because they share his basic values and see the broad public as enjoying the same cultural privileges; but this complicity becomes positively criminal when their common ideology is imposed upon non-capitalist, underdeveloped countries, ignoring the grotesque disparity between the Disney dream of wealth and leisure, and the real needs in the Third World.

It is no accident that the first thoroughgoing analysis of the Disney ideology should come from one of the most economically and culturally dependent colonies of the U.S. empire. How to Read Donald Duck was born in the heat of the struggle to free Chile from that dependency; and it has since become, with its eleven Latin American editions, a most potent instrument for the interpretation of bourgeois media in the Third World.

Until 1970, Chile was completely in pawn to U.S. corporate interests; its foreign debt was the second highest per capita in the world. And even under the Popular Unity government (1970–1973), which initiated the peaceful road to socialism, it proved easier to nationalize copper than to free the mass media from U.S. influence. The most popular TV channel in Chile imported about half its material from the U.S. (including FBI, Mission Impossible, Disneyland, etc.), and until June 1972, eighty percent of the films shown in the cinemas (Chile had virtually no native film industry) came from the U.S. The major chain of newspapers and magazines, including El Mercurio, was owned by Agustin Edwards, a Vice-President of Pepsi Cola, who also controlled many of the largest industrial corporations in Chile, while he was a resident in Miami. With so much of the mass media serving conservative interests, the government of the Popular Unity tried to reach the people through certain alternative media, such as the poster, the mural, and a new kind of comic book.1

The ubiquitous magazine and newspaper kiosks of Chile were emblazoned with the garish covers of U.S. and U.S.-style comics (including some no longer known in the metropolitan country): Superman, The Lone Ranger, Red Ryder, Flash Gordon, etc.—and, of course, the various Disney magazines. In few countries of the world did Disney so completely dominate the so-called “children’s comic” market, a term which in Chile (as in much of the Third World) includes magazines also read by adults. But under the aegis of the Popular Unity government publishing house Quimantú, there developed a forceful resistance to the Disney hegemony.

As part of this cultural offensive, How to Read Donald Duck became a bestseller on publication in late 1971, and subsequently in other Latin American editions; and, as a practical alternative there was created, in Cabro Chico (Little Kid, upon which Dorfman and Mattelart also collaborated), a delightful children’s comic designed to drive a wedge of new values into the U.S.–disnified cultural climate of old. Both ventures had to compete in a market where the bourgeois media were long entrenched and had established their own strictly commercial criteria for the struggle, and both were too successful not to have aroused the hostility of the bourgeois press. El Mercurio, the leading reactionary mass daily in Chile, under the headline “Warning to Parents,”2 denounced them as part of a government “plot” to seize control of education and the media, “brainwash” the young, inject them with “subtle ideological contraband,” and “poison” their minds against Disney characters. The article referred repeatedly to “mentors both Chilean and foreign” (i.e. the authors of the present work, whose names are of German-Jewish and Belgian origin) in an appeal to the crudest kind of xenophobia.

The Chilean bourgeois press resorted to the grossest lies, distortions, and scare campaigns in order to undermine confidence in the Popular Unity government, accusing the government of doing what they aspired to do themselves: censor and silence the voice of their opponents. And seeing that, despite their machinations, popular support for the government grew louder every day, they called upon the military to intervene by force of arms.

On September 11, 1973 the Chilean armed forces executed, with U.S. aid, the bloodiest counterrevolution in the history of the continent. Tens of thousands of workers and government supporters were killed. All art and literature favorable to the Popular Unity was immediately suppressed. Murals were destroyed. There were public bonfires of books, posters, and comics.3 Intellectuals of the Left were hunted down, jailed, tortured, and killed. Among those persecuted, the authors of this book.

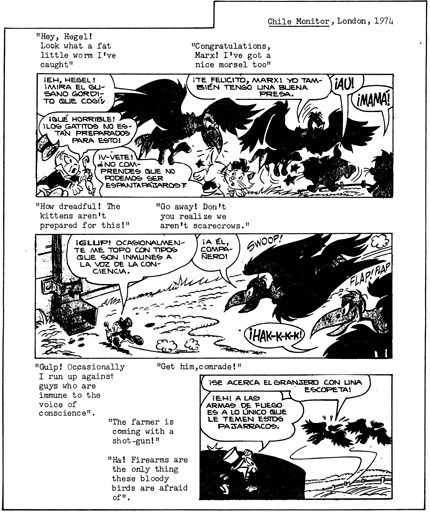

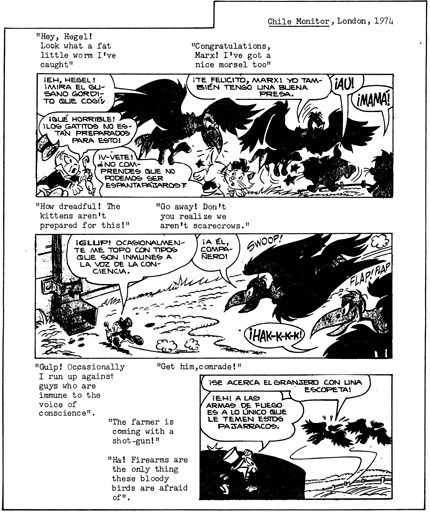

The “state of war” declared by the Junta to exist in Chile, has been openly declared by the Disney comic too. In a recent issue, the Allende government, symbolized by murderous vultures called Marx and Hegel (meaning perhaps, Engels), is being driven off by naked force: “Ha! Firearms are the only things these lousy birds are afraid of.”

How to Read Donald Duck, is now, of course, banned in Chile. To be found in possession of a copy is to risk one’s life. By “cleansing” Chile of every trace of Marxist or popular art and literature, the Junta are protecting the cultural envoys of their imperial masters. They know what kind of culture best serves their interests, that Mickey and Donald will help keep them in power, hold socialism at bay, restore “virtue and innocence” to a “corrupted” Chile.

How to Read Donald Duck is an enraged, satirical, and politically impassioned book. The authors’ passion also derives from a sense of personal victimization, for they themselves, brought up on Disney comics and films, were injected with the Disney ideology which they now reject. But this book is much more than that: it is not just Latin American water off a duck’s back. The system of domination which the U.S. culture imposes so disastrously abroad, also has deleterious effects at home, not least among those who work for Disney, that is, those who produce his ideology. The circumstances in which Disney products are made ensure that his employees reproduce in their lives and work relations the same system of exploitation to which they, as well as the consumer, are subject.

To locate Disney correctly in the capitalist system would require a detailed analysis of the working conditions at Disney Productions and Walt Disney World. Such a study (which would, necessarily, break through the wall of secrecy behind which Disney operates4), does not yet exist, but we may begin to piece together such information as may be gleaned about the circumstances in which the comics are created, and the people who create them; their relationship to their work, and to Disney.

Disney does not take the comics seriously. He hardly even admits publicly of their existence.5 He is far too concerned with the promotion of films and the amusement parks, his two most profitable enterprises. The comics tag along as an “ancillary activity” of interest only insofar as a new comic title (currently Robin Hood) can be used to help keep the name of a new film in the limelight. Royalties from comics constitute a small declining fraction of the revenue from Publications, which constitute a small fraction of the revenue from Ancillary Activities, which constitute a small fraction of the total corporate revenue. While Disney’s share of the market in “educational” and children’s books in other formats has increased dramatically, his cut of the total U.S. comics cake has surely shrunk.

But in foreign lands the Disney comics trade is still a mouse that roars. Many parts of the world, without access to Disney’s films or television shows, know the Disney characters from the comics alone. Those too poor to buy a ticket to the cinema, can always get hold of a comic, if not by purchase, then by borrowing it from a friend. In the U.S. moreover, comic book circulation figures are an inadequate index of the cultural influence of comic book characters. Since no new comedy cartoon shorts have been made of Mickey Mouse since 1948, and of Donald Duck since 1955 (the TV shows carry reruns), it is only in the comic that one finds original stories with the classic characters devised over the last two decades. It is thus the comic books and strips which sustain old favorites in the public consciousness (in the U.S. and abroad) and keep it receptive to the massive merchandizing operations which exploit the popularity of those characters.

Disney, like the missionary Peace Corpsman or “good-will ambassador” of his Public Relations men, has learned the native lingoes—he is fluent in eighteen of them at the moment. In Latin America he speaks Spanish and Portuguese; and he speaks it from magazines which are slightly different, in other ways, from those produced elsewhere and at home. There are, indeed, at least four different Spanish language editions of the Disney comic. The differences between them do not affect the basic content, and to determine the precise significance of such differences would require an excessive amount of research; but the fact of their existence points up some structural peculiarities in this little corner of Disney’s empire. For the Disney comic, more than his other media, systematically relies on foreign labor in all stages of the production process. The native contributes directly to his own colonization.6

Like other multinational corporations, Disney’s has found it profitable to decentralize operations, allowing considerable organizational and production leeway to its foreign subsidiaries or “franchises,” which are usually locked into the giant popular press conglomerates of their respective countries, like Mondadori in Italy or International Press Corporation in Britain. The Chilean edition, like other foreign editions, draws its material from several outside sources apart from the U.S. Clearly, it is in the interests of the metropolis that the various foreign subsidiaries should render mutual assistance to each other, exchanging stories they have imported or produced themselves. Even when foreign editors do not find it convenient to commission stories locally, they can select the type of story, and combination of stories (“story mix”) which they consider suited to particular public taste and particular marketing conditions, in the country or countries they are serving. They also edit (for instance, delete scenes considered offensive or inappropriate to the national sensibility7), have dialogues more or less accurately translated, more or less freely adapted, and add local color (in the literal sense: the pages arrive at the foreign press ready photographed onto black and white transparencies (“mats”), requiring the addition of color as well as dialogue in the local idiom. Some characters like Rockerduck, a freespending millionaire rival of Scrooge; Fethry Duck, a “beatnik” type; and 0.0. Duck, a silly spy; are known only, or chiefly, from the foreign editions, and never caught on at home. The Italians in particular have proven adept in the creation of indigenous characters.

Expressed preferences of foreign editors reveal certain broad differences in taste. Brazil and Italy tend towards more physical violence, more blood and guts; Chile evidently intends (like Scandinavia, Germany, and Holland), to more quiet adventures, aimed (apparently) at a younger age group. Since the military are now in control of education and the mass media in Chile, and are known to be importing Brazilian techniques of repression, one may expect them to also introduce the more violent, Brazilian style of Disney comic.

The tremendous and increasing popularity of Disney abroad is not matched, proportionately, in the home market, where sales have been dropping, to a degree probably exceeding that of other comic classics, ever since the peak reached in the early ’50s. Competition from television is usually cited as a major cause of the slump in the comics market; logistical difficulties of distribution are another; and a third factor, affecting Disney in particular, may be sought in the whole cultural shift of the last two decades, which has transformed the taste of so many of the younger children as well as teenagers in the U.S., and which Disney media appear in many respects to have ignored. If the Disney formula has been successfully preserved in the films and amusement parks even within this changing climate, it is by virtue of an increasingly heavy cloak of technical gimmickry which has been thrown over the old content. Thus the comics, bound today to the same production technology (coloring, printing, etc.) as when they started thirty-five years ago, have been unable to keep up with the new entertainment tricks.

The factors which sent the comics trade into its commercial decline in the U.S. have not weighed to anything like the same extent in the less developed nations of the world. The “cultural lag,” an expression of dominance of the metropolitan center over its colonized areas, is a familiar phenomenon; even in the U.S., Disney comics sell proportionately better in the Midwest and South.

Fueling the foreign market from within the U.S. has in recent years run into some difficulties. The less profitable domestic market, which Disney does not directly control and which now relies heavily on reprints, might conceivably be allowed to wind down altogether. As the domestic market shrinks, Disney pushes harder abroad, in the familiar mechanism of imperialist capitalism. As the foreign market expands, he is under increasing pressure to keep it dependent upon supply from the U.S. (despite or because of the fact that the colonies show, as we have seen, signs of independent productive capacity). But Disney is faced with a recruitment problem, as old workhorses of the profession, like Carl Barks, retire, and others become disillusioned with the low pay and restrictive conditions.

Disney has responded to the need to revitalize domestic production on behalf of the foreign market in a characteristic way: by tightening the rein on worker and product, to ensure that they adhere rigidly to established criteria. Where Disney can exercise direct control, the control must be total.

Prospective freelancers for Disney receive from the Publications Division a sheaf of Comic Book Art Specifications, designed in the first instance for the Comic Book Overseas Program (Western Publishing, which is not primarily beholden to the foreign market, and which is also trying to attract new talent, although perhaps less strenuously, operates by unwritten and less inflexible rules). Instead of inviting the invention of new characters and new locales, the Comic Book Art Specifications do exactly the opposite: they insist that only the established characters be used, and moreover, that there be “no upward mobility. The subsidiary figures should never become stars in our stories, they are just extras.” This severe injunction seems calculated to repress exactly what in the past gave a certain growth potential and flexibility to the Duckburg cast, whereby a minor character was upgraded into a major one, and might even aspire to a comic book of his own. Nor do these established characters have any room to maneuver even within the hierarchical structure where they are immutably fixed; for they are restricted to “a set pattern of behavior which must be complied with.” The authoritarian tone of this instruction to the story writer seems expressly designed to crush any kind of creative manipulation on his part. He is also discouraged from localizing the action in any way, for Duckburg is explicitly stated to be not in the U.S., but “everywhere and nowhere.” All taint of specific geographical location must be expunged, as must all taint of dialect in the language.

Not only sex, but love is prohibited (the relationship between Mickey and Minnie, or Donald and Daisy, is “platonic”—but not a platonic form of love). The gun laws outlaw all firearms but “antique cannons and blunder-busses;” (other) firearms may, under certain circumstances, be waved as a threat, but never used. There are to be no “dirty, realistic business tricks,” no “social differences,”8 or “political ideas.” Above all, race and racial stereotyping is abolished: “Natives should never be depicted as negroes, Malayans, or singled out as belonging to any particular human race, and under no circumstances should they be characterized as dumb, ugly, inferior, or criminal.”

As is evident from the analysis in this book, and as is obvious to anyone at all familiar with the comics, none of these rules (with the exception of the sexual prohibition) have been observed in the past, in either Duck or Mouse stories. Indeed, they have been flouted, time and again. Duckburg is identifiable as a typical small Californian or Midwestern town, within easy reach of forest and desert (like Hemet, California, where Carl Barks, the creator of the best Donald Duck stories lived); the comics are full of Americanisms, in custom and language. Detective Mickey carries a revolver when on assignment, and often gets shot at. Uncle Scrooge is often guilty of blatantly dirty business tricks, and although defined by the Specifications as “not a bad man,” he constantly behaves in the most reprehensible manner (for which he is properly reprehended by the younger ducks). The stories are replete with the “social differences” between rich and penniless (Scrooge and Donald), between virtuous Ducks and unshaven thieves; political ideas frequently come to the fore; and, of course, natives are often characterized as dumb, ugly, inferior, and criminal.

The Specifications seem to represent a fantasy on the studios’ part, a fantasy of control, of a purity which was never really present. The public is supposed to think of the comics, as of Disney in general, in this way; yet the past success of the comics with the public, and their unique character vis-a-vis other comics, has indubitably depended on the prominence given to certain capitalist socio-political realities, like financial greed, dirty business tricks, and the denigration of foreign peoples.

Since a large proportion of the comic stories were always largely produced and published outside the Studios, their content has never, in fact, been under as tight control as the other Disney media. They have clearly benefitted from this. It could be argued that some of the best “non-Disney Disney” stories, those by the creator of Uncle Scrooge, Carl Barks, reveal more than a simplistic, wholly reactionary Disney ideology. There are elements of satire in Barks’ work which one seeks in vain in any other corner of the world of Disney, just as Barks has elements of social realism which one seeks in vain in any other corner of the world of comics. One of the most intelligent students of Barks, Dave Wagner, goes so far as to say that “Barks is the only exception to the uniform reactionary tendencies of the (postwar) Disney empire.”9 But the relationship of Barks to the Disney comics as a whole is a problematical one; if he is responsible for the best of the Duck stories, he is not responsible for all of them, any more than he is responsible for the non-Duck stories; and even those of his stories selected for the foreign editions are sometimes subjected to subtle but significant changes of content. It could be proven that Disney’s bite is worse than his Barks. The handful of U.S. critics who have addressed themselves to the Disney comics have singled out the work of Barks as the superior artist. But the picture which emerges from the U.S. perspective (whether that of a liberal, such as Mike Barrier, or a Marxist, such as Wagner) is that Barks, while in the main clearly conservative in his political philosophy, also reveals himself at times as a liberal, and represents with clarity and considerable wit, the contradictions and perhaps, even some of the anguish, from which U.S. society is suffering. Barks is thus elevated to the ranks of elite bourgeois writing and art, and it is at this level, rather than that of the mass media hack, that criticism in the U.S. addresses itself. At his best, Barks represents a self-conscious guilty bourgeois ideology, from which the mask of innocence occasionally drops (this is especially true of his later works, when he deals increasingly with certain social realities, such as foreign wars, and pollution, etc.).

This outline analysis of the problem of the Disney comic and its relationship to a comparatively sophisticated U.S. audience, demands treatment in depth which I hope to undertake elsewhere. It is strictly irrelevant to the position of Dorfman and Mattelart, and to the Third World struggle for cultural independence.

Dorfman and Mattelart’s book studies the Disney productions and their effects on the world. It cannot be a coincidence that much of what they observe in the relationships between the Disney characters can also be found, and maybe, even explained, in the organization of work within the Disney industry.

The system at Disney Productions seems to be designed to prevent the artist from feeling any pride, or gaining any recognition, other than corporate, for his work. Once the contract is signed, the artist’s idea becomes Disney’s idea. He is its owner, therefore its creator, for all purposes. It says so, in black and white, in the contract: “all art work prepared for our comics magazines is considered work done for hire, and we are the creators thereof for all purposes” (stress added). There could hardly be a clearer statement of the manner in which the capitalist engrosses the labor of his workers. In return for a small fee or wage, he takes from them both the profit and the glory.

Walt Disney, the man who never by his own admission learned to draw, and never even tried to put pencil to paper after around 1926, who could not even sign his name as it appeared on his products, acquired the reputation of being (in the words of a justly famous and otherwise most perceptive political cartoonist) “the most significant figure in graphic art since Leonardo.”10 The man who ruthlessly pillaged and distorted the children’s literature of the world, is hailed (in the citation for the President’s Medal of Freedom, awarded to Disney in 1964) as the “creator of an American folklore.” Throughout his career, Disney systematically suppressed or diminished the credit due to his artists and writers. Even when obliged by Union regulations to list them in the titles, Disney made sure his was the only name to receive real prominence. When a top animator was individually awarded an Oscar for a short, it was Disney who stepped forward to receive it.

While the world applauds Disney, it is left in ignorance of those whose work is the cornerstone of his empire: of the immensely industrious, prolific, and inventive Ub Iwerks, whose technical and artistic innovations run from the multi-plane camera to the character of Mickey himself; of Ward Kimball, whose genius was admitted by Disney himself and who somehow survive Disney’s stated policy of ridding the studios of “anyone showing signs of genius.”11 And of course, Carl Barks, creator of Uncle Scrooge and many other favorite “Disney” characters, of over 300 of the best “Disney” comics stories, of 7,000 pages of “Disney” artwork paid at an average $11.50 per page, not one signed with his name, and selling at their peak from 3–5 million copies; while his employers, trying carefully to keep him ignorant of the true extent of this astonishing commercial success, preserved him from individual fame and from his numerous fans who enquired in vain after his name.

Disney thought of himself as a “pollinator” of people. He was indisputably a fine story editor. He knew how to coordinate labor; above all, he knew how to market ideas. In capitalist economics, both labor and ideas become his property. From the humble inker to the full-fledged animator, from the poor student working as a Disneyland trash-picker to the highly skilled “animatronics” technician, all surrender their labor to the great impresario.

Like the natives and the nephews in the comics, Disney workers must surrender to the millionaire Uncle Scrooge McDisney their treasures—the surplus value of their physical and mental resources. To judge from the anecdotes abounding from the last years of his life, which testify to a pathological parsimony, Uncle Walt was identifying in small as well as big ways less and less with the unmaterialistic Mickey (always used as the personal and corporate symbol), and more and more with Barks’ miser, McDuck.

Literature, too, has been obliged to pour its treasures into the great Disney moneybin. Disney was, as Gilbert Seldes put it many years ago, the “rapacious strip-miner” in the “goldmine of legend and myth.” He ensured that the famous fairy tales became his: his Peter Pan, not Barrie’s, his Pinocchio, not Collodi’s. Authors no longer living, on whose works copyright has elapsed, are of course totally at the mercy of such a predator; but living authors also, confronted by a Disney contract, find that the law is of little avail. Even those favorable to Disney have expressed shock at the manner in which he rides roughshod over the writers of material he plans to turn into a film. The writer of at least one book original has publicly denounced Disney’s brutality.12 The rape is both artistic and financial, psychological and material. A typical contract with an author excludes him or her from any cut in the gross, from royalties, from any share in the “merchandizing bonanza” opened up by the successful Disney film. Disney sews up all the rights for all purposes, and usually for a paltry sum.13

In contrast, to defend the properties he amassed, Disney has always employed what his daughter termed a “regular corps of attorneys”14 whose business it is to pursue and punish any person or organization, however small, which dares to borrow a character, a technique, an idea patented by Disney. The man who expropriated so much from others will not countenance any kind of petty theft against himself. The law has successfully protected Disney against such pilfering, but in recent years, it has had a more heinous crime to deal with: theft compounded by sacrilege. Outsiders who transpose Disney characters, Disney footage, or Disney comic books into unflattering contexts, are pursued by the full rigor of the law. The publisher of an “underground” poster satirizing Disney puritanism by showing his cartoon characters engaged in various kinds of sexual enterprise,15 was sued, successfully, for tens of thousands of dollars worth of damages; and an “underground” comic book artist who dared to show Mickey Mouse taking drugs, is being prosecuted in similar fashion.

Film is a collective process, essentially teamwork. A good animated cartoon requires the conjunction of many talents. Disney’s longstanding public relations image of his studio as one great, happy, democratic family, is no more than a smoke screen to conceal the rigidly hierarchical structure, with very poorly paid inkers and colorers (mostly women) at the bottom of the scale, and top animators (male, of course) earning five times as much as their assistants. In one instance where a top animator objected, on behalf of his assistant, to this gross wage differential, he was fired forthwith.

People were a commodity over which Disney needed absolute control. If a good artist left the studio for another job, he was considered by Disney, if not actually as a thief who had robbed him, then as an accomplice to theft; and he was never forgiven. Disney was the authoritarian father figure, quick to punish youthful rebellion. In post-war years, however, as he grew in fame, wealth, power, and distance, he was no longer regarded by even the most innocent employee as a father figure, but as an uncle—the rich uncle. Always “Walt” to everyone, he had everyone “walt” in.16 “There’s only one S.O.B. in the studio,” he said, “and that’s me.”

For his workers to express solidarity against him was a subversion of his legitimate authority. When members of the Disney studio acted to join an AFL-CIO affiliated union, he fired them and accused them of being Communist or Communist sympathizers. Later, in the McCarthy period, he cooperated with the FBI and HUAC (House Un-American Activities Committee) in the prosecution of an ex-employee for “Communism.”

Ever since 1935, when the League of Nations recognized Mickey Mouse as an “International Symbol of Good Will,” Disney has been an outspoken political figure, and one who has always been able to count upon government help. When the Second World War cut off the extremely lucrative European market, which contributed a good half of the corporate income, the U.S. government helped him turn to Latin America. Washington hastened the solution of the strike which was crippling his studio, and at a time when Disney was literally on the verge of bankruptcy, began to commission propaganda films, which became his mainstay for the duration of the war. Nelson Rockefeller, then Coordinator of Latin American Affairs, arranged for Disney to go as a “good-will ambassador” to the hemisphere, and make a film in order to win over hearts and minds vulnerable to Nazi propaganda. The film, called Saludos Amigos, quite apart from its function as a commercial for Disney, was a diplomatic lesson served upon Latin America, and one which is still considered valid today. The live-action travelogue footage of “ambassador” Disney and his artists touring the continent, is interspersed with animated sections on “life” in Brazil, Argentina, Peru, and Chile, which define Latin America as the U.S. wishes to see it, and as the local peoples are supposed to see it themselves. They are symbolized by comic parrots, merry sambas, luxury beaches, and goofy gauchos, and (to show that even the primitives can be modern) a little Chilean plane which braves the terrors of the Andes in order to deliver a single tourist’s greeting card. The reduction of Latin America to a series of picture postcards was taken further in a later film, The Three Caballeros, and also permeates the comic book stories set in that part of the world.

During the Depression, Disney favorites such as Mickey Mouse and the Three Little Pigs were gratefully received by critics as fitting symbols of courageous optimism in the face of great difficulties. Disney always pooh-poohed the idea that his work contained any particular kind of political message, and proudly pointed (as proof of his innocence) to the diversity of political ideologies sympathetic to him. Mickey, noted the proud parent, was “one matter upon which the Chinese and Japanese agree.” “Mr. Mussolini, Mr. King George and Mr. President Roosevelt” all loved the Mouse; and if Hitler disapproved (Nazi propaganda considered all kinds of mice, even Disney’s, to be dirty creatures)—“Well,” scolded Walt, “Mickey is going to save Mr. A. Hitler from drowning or something one day. Just wait and see if he doesn’t. Then won’t Mr. A. Hitler be ashamed!”17 Come the war, however, Disney was using the Mouse not to save Hitler, but to damn him. Mickey became a favorite armed forces mascot; fittingly, the climactic event of the European war, the Normandy landings, were code-named Mickey Mouse.

Among Disney’s numerous wartime propaganda films, the most controversial and in many ways the most important was Victory through Air Power. Undertaken on Disney’s own initiative, this was designed to support Major Alexander Seversky’s theory of the “effectiveness” (i.e. damage-to-cost ratio) of strategic bombing, including that of population centers. It would be unfair to project back onto Disney our own guilt over Dresden and Hiroshima, but it is noteworthy that even at the time a film critic was shocked by Disney’s “gay dreams of holocaust.”18 And it is consistent that the maker of such a film should later give active and financial support to some noted proponents of massive strategic and terror bombing of Vietnam, such as Goldwater and Reagan. Disney’s support for Goldwater in 1964 was more than the public gesture of a wealthy conservative; he went so far as to wear a Goldwater button while being invested by Johnson with the President’s Medal of Freedom. In the 1959 presidential campaign, he was arrogant enough to bully his employees to give money to the Nixon campaign fund, whether they were Republicans or not.

Disney knew how to adapt to changing cultural climates. His postwar Mouse went “straight;” like the U.S., he became policeman to the world. As a comic he was supplanted by the Duck. Donald Duck represented a new kind of comedy, suited to a new age: a symbol not of courage and wit, as Mickey had been to the ’30s, but an example of heroic failure, the guy whose constant efforts towards gold and glory are doomed to eternal defeat. Such a character was appropriate to the age of capitalism at its apogee, an age presented (by the media) as one of opportunity and plenty, with fabulous wealth awarded to the fortunate and the ruthless competitor, like Uncle Scrooge, and dangled as a bait before the eyes of the unfortunate and the losers in the game.

The ascendancy of the Duck family did not however mean that Mickey had lost his magic. From darkest Africa, Time magazine reported the story of a district officer in the Belgian Congo, coming upon a group of terrified natives screaming “Mikimus.” They were fleeing from a local witchdoctor, whose “usual voo had lost its do, and in the emergency, he had invoked, by making a few passes with needle and thread, the familiar spirit of that infinitely greater magician who has cast his spell upon the entire world—Walt Disney.”19 The natives are here cast, by Time, in the same degraded role assigned to them by the comics themselves.

Back home, meanwhile, the white magic of Disney seemed to be threatened by the virulent black magic of a very different kind of comic. The excesses of the “horror comic” brought a major part of the comic book industry into disrepute, and under the fierce scrutiny of moralists, educators, and child psychologists all over the U.S. and Europe, who saw it as an arena for the horrors of sexual vice, sadism, and extreme physical violence of all kinds.20

Disney, of course, emerged not just morally unscathed, but positively victorious. He became a model for the harmless comic demanded by the new Comics Code Authority. He was now Mr. Clean, Mr. Decency, Mr. Innocent Middle America, in an otherwise rapidly degenerating culture. He was championed by the most reactionary educational officials, such as California State Superintendant of Public Instruction, Dr. Max Rafferty, as “the greatest educator of this century—greater than John Dewey or James Conant or all the rest of us put together.”21 Disney meanwhile (for all his honorary degrees from Harvard, Yale, etc.) continued, as he had always done, to express public contempt for the concepts of “Education,” “Intellect,” “Art,” and the very idea that he was “teaching” anybody anything.

The public Disney myth has been fabricated not only from the man’s works but also from autobiographical data and personal pronouncements. Disney never separated himself from his work; and there are certain formative circumstances of his life upon which he himself liked to enlarge, and which through biographies and interviews, have contributed to the public image of both Disney and Disney Productions. This public image was also the man’s self-image; and both fed into and upon a dominant North American self-image. A major part of his vast audience interpret their lives as he interpreted his. His innocence is their innocence, and vice-versa; his rejection of reality is theirs; his yearning for purity is theirs too. Their aspirations are the same as his; they, like he, started out in life poor, and worked hard in order to become rich; and if he became rich and they didn’t, well, maybe luck just wasn’t on their side.

Walter Elias Disney was born in Chicago in 1901. When he was four, his father, who had been unable to make a decent living in that city as a carpenter and small building contractor, moved to a farm near Marceline, Missouri. Later, Walt was to idealize life there, and remember it as a kind of Eden (although he had to help in the work), as a necessary refuge from the evil world, for he agreed with his father that “after boys reached a certain age they are best removed from the corruptive influences of the big city and subjected to the wholesome atmosphere of the country.22

But after four years of unsuccessful farming, Elias Disney sold his property, and the family returned to the city—this time, Kansas City. There, in addition to his schooling, the eight year old Walt was forced by his father into brutally hard, unpaid work23 as a newspaper delivery boy, getting up at 3:30 every morning and walking for hours in dark, snowbound streets. The memory haunted him all his life. His father was also in the habit of giving him, for no good reason, beatings with a leather strap, to which Walt submitted “to humor him and keep him happy.” This phrase in itself suggests a conscious attempt, on the part of the adult, to avoid confronting the oppressive reality of his childhood.

Walt’s mother, meanwhile, is conspicuously absent from his memories, as is his younger sister. All his three elder brothers ran away from home, and it is a remarkable fact that after he became famous, Walt Disney had nothing to do with either of his parents, or, indeed, any of his family except Roy. His brother Roy, eight years older than himself and throughout his career his financial manager, was from the very beginning a kind of parent substitute, an uncle father-figure. The elimination of true parents, especially the mother, from the comics, and the incidence in the films of mothers dead at the start, or dying in the course of events, or cast as wicked step-mothers (Bambi, Snow White, and especially Dumbo),24 must have held great personal meaning for Disney. The theme has of course long been a constant of world folk-literature, but the manner in which it is handled by Disney may tell us a great deal about 20th century bourgeois culture. Peculiar to Disney comics, surely, is the fact that the mother is not even, technically, missing; she is simply non-existent as a concept. It is possible that Disney truly hated his childhood, and feared and resented his parents, but could never admit it, seeking through his works to escape from the bitter social realities associated with his upbringing. If he hated being a child, one can also understand why he always insisted that his films and amusement parks were designed in the first place for adults, not children, why he was pleased at the statistics which showed that for every one child visitor to Disneyland, there were four adults, and why he always complained at getting the awards for Best Children’s Film.

As Dorfman and Mattelart show, the child in the Disney comic is really a mask for adult anxieties; he is an adult self-image. Most critics are agreed that Disney shows little or no understanding of the “real child,” or real childhood psychology and problems.

Disney has also, necessarily, eliminated the biological link between the parent and child—sexuality. The raunchy touch, the barnyard humor of his early films, has long since been sanitized. Disney was the only man in Hollywood to whom you could not tell a dirty joke. His sense of humor, if it existed at all (and many writers on the man have expressed doubts on this score) was always of a markedly “bathroom” or anal kind. Coy anality is the Disney substitute for sexuality; this is notorious in the films, and observable in the comics also. The world of Disney, inside and outside the comics, is a male one. The Disney organization excludes women from positions of importance. Disney freely admitted “Girls bored me. They still do.”25 He had very few intimate relationships with women; his daughter’s biography contains no hint that there was any real intimacy even within the family circle. Walt’s account of his courtship of his wife establishes it as a purely commercial transaction.26 Walt had hired Lillian Bounds as an inker because she would work for less money than anyone else; he married her (when his brother Roy married, and moved out) because he needed a new roommate, and a cook.

But just as Disney avoided the reality of sex and children, so he avoided that of nature. The man who made the world’s most publicized nature films, whose work expresses a yearning to return to the purity of natural, rustic living, avoided the countryside. He hardly ever left Los Angeles. His own garden at home was filled with railroad tracks and stock (this was his big hobby). He was interested in nature only in order to tame it, control it, cleanse it. Disneyland and Walt Disney World are monuments to his desire for total control of his environment, and at the end of his life he was planning to turn vast areas of California’s loveliest “unspoiled” mountains, at Mineral King, into a 35 million dollar playground. He had no sense of the special non-human character of animals, or of the wilderness; his concern with nature was to anthropomorphize it.

Disney liked to claim that his genius, his creativity “sprouted from mother earth.”27 Nature was the source of his genius, his genius was the source of his wealth, and his wealth grew like a product of nature, like corn. What made his golden cornfield grow? Dollars. “Dollars,” said Disney, in a remark worthy of Uncle Scrooge McDuck, “are like fertilizer—they make things grow.”28

As Dorfman and Mattelart observe, it is Disney’s ambition to render the past like the present, and the present like the past, and project both onto the future. Disney has patented—“sewn up all the rights on”—tomorrow as well as today. For, in the jargon of the media, “he has made tomorrow come true today,” and “enables one to actually experience the future.” His future is currently taking shape in Walt Disney World in Orlando, Florida; an amusement park which covers an area of once virgin land twice the size of Manhattan, which in its first year attracted 10.7 million visitors (about the number who visit Washington, DC annually). With its own laws, it is a state within a state. It boasts of the fifth largest submarine fleet in the world. Distinguished bourgeois architects, town planners, critics, and land speculators have hailed Walt Disney World as the solution to the problems of our cities, a prototype for living in the future. EPCOT (Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow), now in the course of construction, will be, in the words of a well-known critic “a working community, a vast, living, ever-changing laboratory of urban design … (which) understandably … evades a good many problems—housing, schools, employment, politics and so on … They are in the fun business.”29 Of course.

The Disney parks have brought the fantasies of the “future” and the “fun” of the comics one step nearer to capitalist “reality.” “In Disneyland (the happiest place on earth),” says Public Relations, “you can encounter ‘wild’ animals and native ‘savages’ who often display their hostility to your invasion of their jungle privacy … From stockades in Adventureland, you can actually shoot at Indians.”

Meanwhile, out there in the real real world, the “savages” are fighting back.

1975