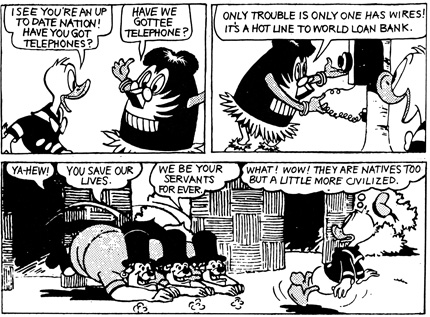

Donald (talking to a witch doctor in Africa): “I see you’re an up to date nation! Have you got telephones?”

Witch doctor: “Have we gottee telephones! … All colors, all shapes … only trouble is only one has wires. It’s a hot line to the world loan bank.”

(TR 106, US 9/64)

Where is Aztecland? Where is Inca-Blinca? Where is Unsteadystan?

There can be no doubt that Aztecland is Mexico, embracing as it does all the prototypes of the picture-postcard Mexico: mules, siestas, volcanoes, cactuses, huge sombreros, ponchos, serenades, machismo, and Indians from ancient civilizations. The country is defined primarily in terms of this grotesque folklorism. Petrified in an archetypical embryo, exploited for all the superficial and stereotyped prejudices which surround it, “Aztecland,” under its pseudo-imaginary name becomes that much easier to Disnify. This is Mexico recognizable by its commonplace exotic identity labels, not the real Mexico with all its problems.

Walt took virgin territories of the U.S. and built upon them his Disneyland palaces, his magic kingdoms. His view of the world at large is framed by the same perspective; it is a world already colonized, with phantom inhabitants who have to conform to Disney’s notions of it. Each foreign country is used as a kind of model within the process of invasion by Disney-nature. And even if some foreign country like Cuba or Vietnam should dare to enter into open conflict with the United States, the Disney Comics brand-mark is immediately stamped upon it, in order to make the revolutionary struggle appear banal. While the Marines make revolutionaries run the gauntlet of bullets, Disney makes them run a gauntlet of magazines. There are two forms of killing: by machine guns and saccharine.

Disney did not, of course, invent the inhabitants of these lands; he merely forced them into the proper mold. Casting them as stars in his hit-parade, he made them into decals and puppets for his fantasy palaces, good and inoffensive savages unto eternity.

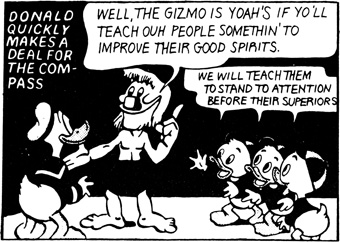

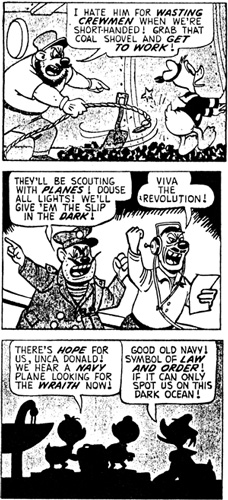

According to Disney, underdeveloped peoples are like children, to be treated as such, and if they don’t accept this definition of themselves, they should have their pants taken down and be given a good spanking. That’ll teach them! When something is said about the child/noble savage, it is really the Third World one is thinking about. The hegemony which we have detected between the child-adults who arrive with their civilization and technology, and the child-noble savages who accept this alien authority and surrender their riches, stands revealed as an exact replica of the relations between metropolis and satellite, between empire and colony, between master and slave. Thus we find the metropolitans not only searching for treasures, but also selling the native comics (like those of Disney), to teach them the role assigned to them by the dominant urban press. Under the suggestive title “Better Guile Than Force,” Donald departs for a Pacific atoll in order to try to survive for a month, and returns loaded with dollars, like a modern business tycoon. The entrepreneur can do better than the missionary or the army. The world of the Disney comic is self-publicizing, ensuring a process of enthusiastic buying and selling even within its very pages.

Enough of generalities. Examples and proofs. Among all the child-noble savages, none is more exaggerated in his infantilism than Gu, the Abominable Snow Man (TR 113, US 6-8/56, “The Lost Crown of Genghis Khan”): a brainless, feeble-minded Mongolian type (living by a strange coincidence, in the Himalayan Hindu Kush mountains among yellow peoples). He is treated like a child. He is an “abominable housekeeper,” living in a messy cave, “the worst of taste,” littered with “cheap trinkets and waste.” Hats etc., lying around which he has no use for. Vulgar, uncivilized, he speaks in a babble of inarticulate baby-noises: “Gu.” But he is also witless, having stolen the golden jewelled crown of Genghis Khan (which belongs to Scrooge by virtue of certain secret operations of his agents), without having any idea of its value. He has tossed the crown in a corner like a coal bucket, and prefers Uncle Scrooge’s watch: value, one dollar (“It is his favorite toy”). Never mind, for “his stupidity makes it easy for us to get away!” Uncle Scrooge does indeed manage, magically, to exchange the cheap artifact of civilization which goes tick-tock, for the crown. Obstacles are overcome once Gu (innocent child-monstrous animal—underdeveloped Third Worldling) realizes that they only want to take something that is of no use to him, and that in exchange he will be given a fantastic and mysterious piece of technology (a watch) which he can use as a plaything. What is extracted is gold, a raw material; he who surrenders it is mentally underdeveloped and physically overdeveloped. The gigantic physique of Gu, and of all the other marginal savages, is the model of a physical strength suited only for physical labor.1

Such an episode reflects the barter relationship established with the natives by the first conquistadors and colonizers (in Africa, Asia, America, and Oceania): some trinket, the product of technological superiority (European or North American) is exchanged for gold (spices, ivory, tea, etc.). The native is relieved of something he would never have thought of using for himself or as a means of exchange. This is an extreme and almost anecdotal example. The common stuff of other types of comic book (e.g. in the internationally famous Tintin in Tibet by the Belgian Hergé) leaves the abominable creature in his bestial condition, and thus unable to enter into any kind of economy.

But this particular victim of infantile regression stands at the borderline of Disney’s noble savage cliché. Beyond it lies the foetus-savage, which for reasons of sexual prudery Disney cannot use.

Lest the reader feel that we are spinning too fine a thread in establishing a parallel between someone who carries off gold in exchange for a mechanical trinket, and imperialism extracting raw material from a mono-productive country, or between typical dominators and dominated, let us now adduce a more explicit example of Disney’s strategy in respect to the countries he caricatures as “backward” (needless to say, he never hints at the causes of their backwardness).

The following dialogue (taken from the same comic which provided the quotation at the beginning of this chapter) is a typical example of Disney’s colonial attitudes, in this case directed against the African independence movements. Donald has parachuted into a country in the African jungle. “Where am I,” he cries. A witch doctor (with spectacles perched over his gigantic primitive mask) replies: “In the new nation of Kooko Coco, fly boy. This is our capital city.” It consists of three straw huts and some moving haystacks. When Donald enquires after this strange phenomenon, the witch doctor explains: “Wigs! This be hairy idea our ambassador bring back from United Nations.” When a pig pursuing Donald lands and has the wigs removed disclosing the whereabouts of the enemy ducks, the following dialogue ensues:

Pig: “Hear ye! hear ye! I’ll pay you kooks some hairy prices for your wigs! Sell me all you have!”

Native: “Whee! Rich trader buyee our old head hangers!”

Another native: “He payee me six trading stamps for my beehive hairdo!”

Third native (overjoyed): “He payee me two Chicago streetcar tokens for my Beatle job.”

To effect his escape, the pig decides to scatter a few coins as a decoy. The natives are happy to stop, crouch, and cravenly gather up the money. Elsewhere, when the Beagle Boys dress up as Polynesian natives to deceive Donald, they mimic the same kind of behavior; “You save our lives … We be your servants forever.” And as they prostrate themselves, Donald observes: “They are natives too. But a little more civilized.”

Another example (Special Number D 423): Donald leaves for “Outer Congolia,” because Scrooge’s business there has been doing badly. The reason is that “the King ordered his subjects not to give Christmas presents this year. He wants everyone to hand over this money to him.” Donald comments: “What selfishness!” And so to work. Donald makes himself king, being taken for a great magician who flies through the skies. The old monarch is dethroned because “he is not a wise man like you [Donald]. He does not permit us to buy presents.” Donald accepts the crown, intending to decamp as soon as the stock is sold out: “My first command as king is … buy presents for your families and don’t give your king a cent!” The old king had wanted the money to leave the country and eat what he fancied, instead of the fish heads which were traditionally his sole diet. Repentant, he promises that given another chance, he will govern better, “and I will find a way somehow to avoid eating that ghastly stew.”

Donald (to the people): “And I assure you that I leave the throne in good hands. Your old king is a good king … and wiser than before.” The people: “Hurray! Long live the King!”

The king has learned that he must ally himself with foreigners if he wishes to stay in power, and he cannot even impose taxes on the people, because this wealth must pass wholly out of the country to Duckburg through the agent of McDuck. Furthermore, the strangers find a solution to the problem of the king’s boredom. To alleviate his sense of alienation within his own country, and his consequent desire to travel to the metropolis, they arrange for the massive importation of consumer goods: “Don’t worry about that food,” says Donald, “I will send you some sauces which will make even fish heads palatable.” The king stamps gleefully up and down.

The same formula is repeated over and over again. Scrooge exchanges with the Canadian Indians gates of rustless steel for gates of pure gold (TR 117). Moby Duck and Donald (D 453), captured by the Aridians (Arabs), start to blow soap bubbles, with which the natives are enchanted. “Ha, ha. They break when you catch them. Hee, hee.” Ali-Ben-Goli, the chief says. It’s real magic. My people are laughing like children. They cannot imagine how it works.” “It’s only a secret passed from generation to generation,” says Moby, “I will reveal it if you give us our freedom.” (Civilization is presented as something incomprehensible, to be administered by foreigners). The chief, in amazement, exclaims “Freedom? That’s not all I’ll give you. Gold, Jewels. My treasure is yours, if you reveal the secret.” The Arabs consent to their own despoliation. “We have jewels, but they are of no use to us. They don’t make you laugh like magic bubbles.” While Donald sneers “poor simpleton,” Moby hands over the Flip Flop detergent. “You are right, my friend. Whenever you want a little pleasure, just pour out some magic powder and recite the magic words.” The story ends on the note that it is not necessary for Donald to excavate the Pyramids (or earth) personally, because, as Donald says, “What do we need a pyramid for, having Ali-Ben-Goli?”

Each time this situation recurs, the natives’ joy increases. As each object of their own manufacture is taken away from them, their satisfaction grows. As each artifact from civilization is given to them, and interpreted by them as a manifestation of magic rather than technology, they are filled with delight. Even our fiercest enemies could hardly justify the inequity of such an exchange; how can a fistful of jewels be regarded as equivalent to a box of soap, or a golden crown equal to a cheap watch? Some will object that this kind of barter is all imaginary, but it is unfortunate that these laws of the imagination are tilted unilaterally in favor of those who come from outside, and those who write and publish the magazines.

But how can this flagrant despoliation pass unperceived, or in other words, how can this inequity be disguised as equity? Why is it that imperialist plunder and colonial subjection, to call them by their proper names, do not appear as such?

“We have jewels, but they are of no use to us.”

There they are in their desert tents, their caves, their once flourishing cities, their lonely islands, their forbidden fortresses, and they can never leave them. Congealed in their past-historic, their needs defined in function of this past, these underdeveloped peoples are denied the right to build their own future. Their crowns, their raw materials, their soil, their energy, their jade elephants, their fruit, but above all, their gold, can never be turned to any use. For them the progress which comes from abroad in the form of multiplicity of technological artifacts, is a mere toy. It will never penetrate the crystallized defense of the noble savage, who is forbidden to become civilized. He will never be able to join the Club of the Producers, because he does not even understand that these objects have been produced. He sees them as magic elements, arising from the foreigner’s mind, from his word, his magic wand.

Since the noble savage is denied the prospect of future development, plunder never appears as such, for it only eliminates that which is trifling, superfluous, and dispensable. Unbridled capitalist despoliation is programmed with smiles and coquetry. Poor native. How naïve they are. And since they cannot use their gold, it is better to remove it. It can be used elsewhere.

Scrooge McDuck gets hold of a twenty-four carat moon in which “the gold is so pure that it can be molded like butter.” (TR 48, US 12-2/59). But the legitimate owner appears, a Venusian called Muchkale, who is prepared to sell it to Scrooge for a fistful of earth. “Man! That’s the biggest bargain I ever heard of in all history,” cries the miser as he closes the deal. But Muchkale, who is a “good native,” magically transforms the fistful of earth into a planet, with continents, oceans, trees, and a whole environment of nature, “Yessir! I was quite impoverished here, with only atoms of gold to work with!” he says. Exiled from his state of primitive innocence, longing for some rain and volcanoes, Muchkale rejects his gold in order to return to the land of his origin and content himself with life at subsistence level. “Skunk Cabbage! [his favorite dish on Venus] I live again … Now I have a world of my own, with food and drink and life!” Far from robbing him, Scrooge has done Muchkale a favor by removing all that corrupt metal and facilitating his return to primitive innocence. “He got the dirt he wanted, and I got this fabulous twenty-four carat moon. Five hundred miles thick! Of solid gold! But doggoned if I don’t think he got the best of the bargain!” Poor, but happy, the Venusian is left devoting himself to the celebration of the simple life. It’s the old aphorism, the poor have no worries, it is the rich who have all the problems. So let’s have no qualms about plundering the poor and underdeveloped.

Conquest has been purged. Foreigners do no harm, they are building the future, on the basis of a society which cannot and will not leave the past.

But there is another way of infantilizing others and exonerating one’s own larcenous behavior. Imperialism likes to promote an image of itself as being the impartial judge of the interests of the people, and their liberating angel.

The only thing which cannot be taken from the noble savage is his subsistence living, because losing this would destroy his natural economy, forcing him to abandon Paradise for Mammon and a production economy.

Donald travels to the “Plateau of Abandon” to look for a silver goat, which his Problem Solving Agency has contracted to find for a rich customer. He finds the goat, but breaks it while trying to ride it, and then discovers that this animal—and nothing else—stands between life and death by starvation (forbidden word) for the primitive people who live near the plateau. What had brought this to pass? Some time ago, an earthquake cut off the people and their flocks from their ancient pasturelands. “We would have died of hunger in this patch of earth if a generous white man had not arrived here in that mysterious bird over there [i.e. an aircraft] … and made a white goat with the metal from our mine.” It is this mechanical goat which leads the flocks of sheep through the dangerous ravine to pasture in the outlying plains, and without it, the sheep get lost. The natives admire the way Donald & Co. decide to venture back through perilous precipices “which only you and the sheep have the courage to cross. Our people have never had a head for heights.” Once through the ravine, Donald and nephews mend the goat and bring the sheep safely back to their owners.

Enter at this point the villains: the rich Mr. Leech and his spoiled son who had contracted and sent Donald off in search of the goat. “You signed the contract and must hand over the goods.” But the evil party is defeated and the ducks reveal themselves as disinterested friends of the natives. Trusting the ducks as they did their Duckburg predecessor, the natives enter into an alliance with the good foreigners against the bad foreigners. The moral Manichaeism serves to affirm foreign sovereignty in its authoritarian and paternalist role. Big Stick and Charity.2 The good foreigners, under their ethical cloak, win with the native’s confidence, the right to decide the proper distribution of wealth in the land. The villains; course, vulgar, repulsive, out-and-out thieves, are there purely and simply to reveal the ducks as defenders of justice, law, and food for the hungry, and to serve as a whitewash for any further action. Defending the only thing that the noble savage can use (their food), the lack of which would result in their death (or rebellion, either of which would violate their image of infantile innocence), the big city folk establish themselves as the spokesman of these submerged and voiceless peoples.

The ethical division between the two classes of predators, the would-be robbers working openly, and the actual ones working surreptitiously, is constantly repeated. In one episode (TB 62), Mickey and company search for a silver mine and unmask two crooks. The crooks, disguised as Spanish conquistadors, who had originally stolen the mineral, are terrorizing the Indians, and are now making great profits from tourists by selling them “Indian ornaments.” The constant characteristic of the natives—irrational fear and panic when faced with any phenomenon which disrupts their natural rhythm of life—serves to emphasize their cowardice (rather like children afraid of the dark), and to justify the necessity that some superior being come to their rescue and bring daylight. As reward for catching the crooks, the heroes are given ranks within the tribe; Minnie, princess; Mickey and Goofy, warriors; and Pluto gets a feather. And, of course, Duckburg gets the “Indian ornaments.” The Indians have been given the “freedom to sell their goods on the foreign market.” It is only direct and open robbery without offering a share in the profits, which is to be condemned. Mickey’s imperialist despoliation is a foil for that of the Spaniards and those who, in the past, undeniably robbed and enslaved the natives more openly.

Things are different nowadays. To rob without payment is robbery undisguised. Taking with payment is no robbery, but a favor. Thus the conditions for the sale of the ornaments and their importation into Duckburg are never in question, for they are based on the supposition of equality between the two negotiating partners.

An isolated tribe of Indians find themselves in a similar situation (D 430, DD 3/66, “Ambush at Thunder Mountain”). They “have declared war on all Ducks” on the basis of a previous historical experience. Buck Duck, fifty years before (and nothing has changed since then) cheated them doubly: first stealing the natives’ land, and then, selling it back to them in a useless condition. So it is a matter of convincing them that not all ducks (white men) are evil, that the frauds of the past can be made good. Any history book—even Hollywood, even television—admits that the natives were violated. The history of fraud and exploitation of the past is public knowledge and cannot be buried any longer, and so it appears over and done with. But the present is another matter.

In order to assure the redemptive powers of present-day imperialism, it is only necessary to measure it against old-style colonialism and robbery. Example: Enter a pair of crooks determined to cheat the natives of their natural gas resources. They are unmasked by the ducks, who are henceforth regarded as friends.

“Let’s bury the hatchet, let’s collaborate, the races can get along together.” What a fine message! It couldn’t have been said better by the Bank of America, who, in sponsoring the mini-city of Disneyland in California, calls it a world of peace where all peoples can get along together.

But what happens to the lands?

“A big gas company will do all the work, and pay your tribe well for it.” This is the most shameless imperialist politics. Facing the relatively crude crooks of the past and present (handicapped, moreover, by their primitive techniques), stands the sophisticated Great Uncle Company, which will resolve all problems equitably. The guy who comes in from the outside is not necessarily a bad ’un, only if he fails to pay the “fair and proper price.” The Company, by contrast, is benevolence incarnate.

This form of exploitation is not all. A Wigwam Motel and a souvenir shop are opened, and excursions are arranged. The Indians are immobilized against their national background and served up for tourist consumption.

The last two examples suggest certain differences from the classic politics of bare-faced colonialism. The benevolent collaboration figuring in the Disney comics suggests a form of neocolonialism which rejects the naked pillage of the past, and permits the native a minimal participation in his own exploitation.

Perhaps the clearest manifestation of this phenomenon is a comic (D 432, DD 9/65, “Treasure of Aztecland”) written at the height of the Alliance for Progress program about the Indians of Aztecland who at the time of the Conquest had hidden their treasure in the jungle. Now they are saved by the Ducks from the new conquistadors, the Beagle Boys. “This is absurd! Conquistadors don’t exist any more!” The pillage of the past was a crime. As the past is criminalized, and the present purified, its real traces are effaced from memory. There is no need to keep the treasure hidden: the Duckburgers (who have already demonstrated their kindness of heart by charitably caring for a stray lamb) will be able to defend the Mexicans. Geography becomes a picture postcard, and is sold as such. The days of yore cannot advance or change, because this would damage the tourist trade. “Visit Aztecland. Entrance: One Dollar.” The vacations of the big city people are transformed into a modern vehicle of supremacy, and we shall see later how the natural and physical virtues of the noble savage are preserved intact. A holiday in these places is like a loan, or a blank check on purification and regeneration through communion with nature.

All these examples are based upon common international stereotypes. Who can deny that the Peruvian (in Inca-Blinca, TB 104) is somnolent, sells pottery, sits on his haunches, eats hot peppers, has a thousand-year-old culture—all the dislocated prejudices proclaimed by the tourist posters themselves? Disney does not invent these caricatures, he only exploits them to the utmost. By forcing all peoples of the world into a vision of the dominant (national and international) classes, he gives this vision coherency and justifies the social system on which it is based. These clichés are also used by the mass culture media to dilute the realities common to these people. The only means that the Mexican has of knowing Peru is through caricature, which also implies that Peru is incapable of being anything else, and is unable to rise above this prototypical situation, imprisoned as it is made to seem, within its own exoticism. For Mexican and Peruvian alike, these stereotypes of Latin American peoples become a channel of distorted self-knowledge, a form of self-consumption, and finally, self-mockery. By selecting the most superficial and singular traits of each people in order to differentiate them, and using folklore as a means to “divide and conquer” nations occupying the same dependent position, the comic, like all mass media, exploits the principle of sensationalism. That is, it conceals reality by means of novelty, which not incidentally, also serves to promote sales. Our Latin American countries become trash cans being constantly repainted for the voyeuristic and orgiastic pleasures of the metropolitan nations. Every day, this very minute, television, radio, magazines, newspapers, cartoons, newscasts, films, clothing, and records, from the dignified gab of history textbooks to the trivia of daily conversation, all contribute to weakening the international solidarity of the oppressed. We Latin Americans are separated from each other by the vision we have acquired of each other via the comics and the other mass culture media. This vision is nothing less than our own reduced and distorted image.

This great tacit pool overflowing with the riches of stereotype is based upon common clichés, so that no one needs to go directly to sources of information gathered from reality itself. Each of us carries within a Boy Scout Handbook packed with the commonplace wisdom of Everyman.

Contradictions flourish, however, and this is fortunate. When they become so blatant as to constitute, in spite of metropolitan press, news, it is impossible to maintain the same old unruffled storyline. The open conflict can no longer be concealed by the same formulas as the situation which, although inherently conflictive, is not yet explosive enough to be considered newsworthy.

The diseases of the system are manifest on many levels. The artist who shatters the habits of vision imposed by the mass media, who attacks the spectator and undermines his stability, is dismissed as a mere eccentric, who happens to cast colors or words in the wind. The genius is isolated from real life, and all his attempts to reconcile reality with its aesthetic representation, are neutralized. He is caricatured in Goofy, who wins the first prize in the “pop” art contest, by sliding crazily through a parking lot overturning paint cans and creating chaos (TB 99, DD 11/67). Amidst the artistic trash that he has generated, Goofy cries: “Me [the winner]! Gawrsh! I wasn’t even trying!” And art loses its offensive character: “This sure is easy work. At last I can earn money and have fun at the same time, and no one gets mad at me.” The public has no reason to be disconcerted by these “masterpieces”: they bear no relation to their lives, only the weak and stupid devote themselves to that kind of sport. The same thing happens with the “hippies,” “love-ins,” and peace marches. In one episode (TR 40, US 12/63) a gang of irate people (observe the way they are lumped together) march fanatically by, only to be decoyed by Donald towards his lemonade stand, with the shout “There’s a thirsty-looking group. Hey people, throw down your banners and have free lemonades!” Setting peace aside, they descend upon Donald like a herd of buffaloes, snatching his money, and slurping noisily. Moral: see what hypocrites these rioters are; they sell their ideals for a glass of lemonade.

In contrast, there stands another group also drinking lemonade, but in orderly fashion—little cadets, disciplined, obedient, clean, good-looking, and truly pacific; no dirty, anarchic “rebels” they.

This strategy, by which protest is converted into imposture, is called dilution: banalize an unusual phenomenon of the social body and symptom of a cancer, in such a way that it appears as an isolated incident removed from its social context, so that it then can be automatically rejected by “public opinion” as a passing itch. Just give yourself a scratch, and be done with it. Disney did not, of course, get this little light bulb all on his own. It is part of the metabolism of the system, which reacts to the facts of a situation by trying to absorb and eliminate them. It is part of a strategy, consciously or unconsciously orchestrated.

For example, the adoption by the fashion industry of the primitive dynamite of the hippie is designed to neutralize its power of denunciation. Or, the attempts of advertising, in the U.S., to liquify the concept of the women’s liberation movements. “Liberate” yourself by buying a new mixer or dishwasher. This is the real revolution: new styles, low prices. Airplane hijacking (TR 113) is emptied of its social-political significance and is presented as the work of crazy bandits, “From what we read in the papers, hijacking has become very fashionable.” Thus, the media minimize the matter and its implications, and reassure the public that nothing is really going on.

But all these phenomena are merely potentially subversive, mere straws in the wind. Should there emerge any phenomenon truly flouting the Disney laws of creation which govern the exemplary and submissive behavior of the noble savage, this cannot remain concealed. It is brought out garnished, prettified, and reinterpreted for the reader, who being young, must be protected. This second strategy is called recuperation: the utilization of a potentially dangerous phenomenon of the social body in such a way that it serves to justify the continued need of the social system and its values, and very often justifies the violence and repression which are part of that system.

Such is the case of the Vietnam War, where protest was manipulated to justify the vitality and values of the system which produced the war, not to end the injustice and violence of the war itself. The “ending” of the war was only a problem of “public opinion.”

The realm of Disney is not one of fantasy, for it does react to world events. Its vision of Tibet is not identical to its vision of Indochina. Fifteen years ago the Caribbean was a sea of pirates. Disney has had to adjust to the fact of Cuba and the invasion of the Dominican Republic. The buccaneer now cries “Viva the Revolution,” and has to be defeated. It will be Chile’s turn yet.

Searching for a jade elephant, Scrooge and his family arrive in Unsteadystan, “where every thug wants to be ruler,” and “where there is always someone shooting at someone else.” (TR 99, US 7/66, “Treasure of Marco Polo”). A state of civil war is immediately turned into an incomprehensible game of someone-or-other against someone-or-other, a stupid fratricide lacking in any ethical direction or socio-economic raison d’etre. The war in Vietnam becomes a mere interchange of unconnected and senseless bullets, and a truce becomes a siesta. “Wahn Beeg Rhat, yes, Duckburg, no!” cries a guerilla in support of an ambitious (communist) dictator, as he dynamites the Duckburg embassy. Noticing that his watch is not working properly, the Vietcong (no less) mutters “Shows you can’t trust these watches from the ‘worker’s paradise.’” The struggle for power is purely personal, the eccentricity of ambition: “Hail to Wahn Beeg Rhat, dictator of all the happy people,” goes the cry and sotto voce “happy or not.” Defending his conquest, the dictator gives orders to kill. “Shoot him, don’t let him spoil my revolution.” The savior in this chaotic situation is Prince Char Ming, also known [in the Spanish version] as Yho Soy [“I am”—the English is Soy Bheen], names expressive of his magical egocentricity. He comes to reunify the country and “pacify” the people. He is destined to triumph, because the soldiers refuse to obey the orders of a leader who has lost his charisma, who is not “Char Ming.” So one guerrilla wonders why they “keep these silly revolutions going forever.” Another denounces them, demanding a return to the King, “like in the good old days.”

In order to close the circuit and the alliance between Duckburg and Prince Char Ming, Scrooge McDuck presents to Unsteadystan the treasure and the jade elephant which once had belonged to the people of that country. One of the nephews observes: “They will be of use to the poor.” And finally, Scrooge, in his haste to get out of this parody of Vietnam, promises “When I return to Duckburg, I will do even more for you. I will return the million dollar tail of the jade elephant.”

But we can bet that Scrooge will forget his promises as soon as he gets back. As proof we find in another comic book (D 445) the following dialogue which takes place in Duckburg:

Nephew: “They got the Asiatic flu as well.”

Donald: “I’ve always said that nothing good could come out of Asia.”

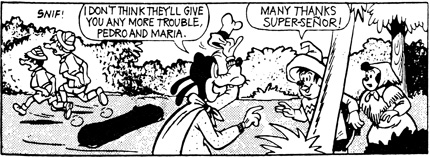

A similar reduction of a historical situation takes place in the Republic of San Bananador, obviously in the Caribbean or Central America (D 364, CS 4/64, “Captain Blight’s Mystery Ship”). Waiting in a port, Donald makes fun of the children playing at being shanghaied: These things just don’t happen anymore; shanghai-ing, weevly beans, walking the plank, pirate-invested seas—these are all things of the past. But it turns out that there are places where such horrors still survive, and the nephew’s game is soon interrupted by a man trying to escape from a ship carrying a dangerous cargo and commanded by a captain who is a living menace. Terror reigns on board. When the man is forcibly brought back to the ship, he invokes the name of liberty (“I’m a free man! Let me go!”), while his kidnappers treat him as a slave. Although Donald, typically, makes light of the incident (“probably only a little rhubarb about wages,” or “actors making a film”), he and his nephews are also captured. Life on board is a nightmare; the food is weevly beans, even the rats are prevented from leaving the ship, and there is forced labor, with slaves, slaves, and more slaves. All is subject to the unjust, arbitrary, and crazy rule of Captain Blight and his bearded followers.

Surely these must be pirates from olden days. Absolutely not. They are revolutionaries (Cuban, no less) fighting against the government of San Bananador, and pursued by the navy for trying to supply rebels with a shipment of arms. “They’ll be scouting with planes! Douse all lights! We’ll give ’em the slip in the dark!” And the radio operator, fist raised on high, shouts: “Viva the Revolution!” The only hope, according to Donald, is “the good old navy, symbol of law and order.” The rebel opposition is thus automatically cast in the role of tyranny, dictatorship, totalitarianism. The slave society reigning on board ship is the replica of the society which they propose to install in place of the legitimately established regime. Apparently, in modern times it is the champions of popular insurgency who will bring back human slavery.

The political drift of Disney is blatant in these few comics where he is impelled to reveal his intentions openly. It is also inescapable in the bulk of them, where he uses animal symbolism, infantilism, and “noble savagery” to cover over the network of interests arising from a concrete and historically determined social system: U.S. imperialism.

The problem is not only Disney’s equation of the child with the noble savage, and the noble savage with the underdeveloped peoples. It is also—and here is the crux of the matter—that what is said, referred to, revealed, and disguised about all of them, has, in fact, only one true object: the working class.

The imaginative world of the child has become the political utopia of a social class. In the Disney comics, one never meets a member of the working or proletarian classes, and nothing is the product of an industrial process. But this does not mean that the worker is absent. On the contrary: he is present under two masks, that of the noble savage and that of the criminal-lumpen. Both groups serve to destroy the worker as a class reality, and preserve certain myths which the bourgeoisie have from the very beginning been fabricating and adding to in order to conceal and domesticate the enemy, impede his solidarity, and make him function smoothly within the system and cooperate in his own ideological enslavement.

In order to rationalize their dominance and justify their privileged position, the bourgeoisie divided the world of the dominated as follows: first, the peasant sector, which is harmless, natural, truthful, ingenuous, spontaneous, infantile, and static; second, the urban sector, which is threatening, teeming, dirty, suspicious, calculating, embittered, vicious, and essentially mobile. The peasant acquires in this process of mythification the exclusive property of being “popular,” and becomes installed as a folk-guardian of everything produced and preserved by the people. Far from the influence of the steaming urban centers, he is purified through a cyclical return to the primitive virtues of the earth. The myth of the people as noble savage—the people as a child who must be protected for its own good—arose in order to justify the domination of a class. The peasants were the only ones capable of becoming incontrovertible vehicles for the permanent validity of bourgeois ideals. Juvenile literature fed on these “popular” myths and served as a constant allegorical testimony to what the people were supposed to be.

Each great urban civilization (Alexandria for Theocritus, Rome for Virgil, the modern era for Sannazaro, Montemayor, Shakespeare, Cervantes, d’Urfé) created its pastoral myth: an extra-social Eden chaste and pure. Together with this evangelical bucolism, there emerged a picturesque literature teeming with ruffians, vagabonds, gamblers, gluttons, etc., who reveal the true nature of urban man; mobile, degenerate, irredeemable. The world was divided between the lay heaven of the shepherds, and the terrestrial inferno of the unemployed. At the same time, a utopian literature flourished (Thomas More, Tommaso Campanella), projecting into the future on the basis of an optimism fostered by technology, and a pessimism resulting from the breakdown of medieval unity, the ecstatic realm of social perfection. The rising bourgeoisie, which gave the necessary momentum to the voyages of discovery, found innumerable peoples who theoretically corresponded to their pastoral-utopian schemata; their ideal of universal Christian reason proclaimed by Erasmian humanism. Thus the division between positive-popular-rustic and negative-popular-proletarian was overwhelmingly reinforced. The new continents were colonized in the name of this division; to prove that removed from original sin and mercantilist taint, these continents might be the site for the ideal history which the bourgeoisie had once imagined for themselves at home. An ideal history which was ruined and threatened by the constant opposition of the idle, filthy, teeming, promiscuous, and extortionary proletarians.

In spite of the failure in Latin America, in spite of the failure in Africa, Oceania, and in Asia, the myth never lost its vitality. On the contrary, it served as a constant spur in the only country which was able to develop it still further. By opening the frontier further and further, the United States elaborated the myth and eventually gave birth to a “Way of Life” and ideology shared by the infernal Disney. A man, who in trying to open and close the frontier of the child’s imagination, based himself precisely on those now-antiquated myths which gave rise to his own country.

The historical nostalgia of the bourgeoisie, so much the product of its objective contradictions—its conflicts with the proletariat, the difficulties arising from the industrial revolution, as the myth was always belied and always renewed—this nostalgia took upon itself a twofold disguise, one geographical: the lost paradise which it could not enjoy, and the other biological: the child who would serve to legitimize its plans for human emancipation. There was no other place to flee, unless it was to that other nature, technology.

The yearning of a McLuhan, the prophet of the technological era, to use mass communications as a means of returning to the “planetary village” (modelled upon the “primitive tribal communism” of the underdeveloped world), is nothing but a utopia of the future which revives a nostalgia of the past. Although the bourgeoisie were unable, during the centuries of their existence, to realize their imaginary historical design, they kept it nice and warm in every one of their expeditions and justifications. Disney characters are afraid of technology and its social implications; they never fully accept it; they prefer the past. McLuhan is more farsighted: he understands that to interpret technology as a return to the values of the past is the solution which imperialism must offer in the next stage of its strategy.

But our next stage is to ask a question which McLuhan never poses: if the proletariat is eliminated, who is producing all that gold, all those riches?