“If I were able to produce money with my black magic, I wouldn’t be in the middle of the desert looking for gold, would I?”

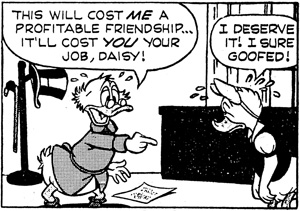

Magica de Spell (TR 111)

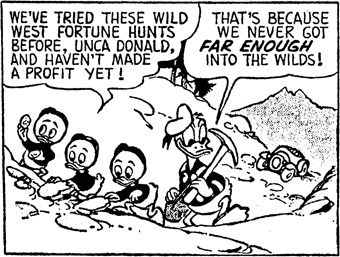

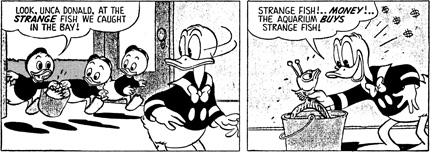

What are these adventurers escaping from their claustrophobic cities really after? What is the true motive of their flight from the urban center? Bluntly stated: in more than seventy-five percent of our sampling they are looking for gold, in the remaining twenty-five percent they are competing for fortune—in the form of money or fame—in the city.

Why should gold, criticized ever since the beginning of a monetary economy as a contamination of human relations and the corruption of human nature, mingle here with the innocence of the noble savage (child and people)? Why should gold, the fruit of urban commerce and industry, flow so freely from these rustic and natural environments?

The answer to these questions lies in the manner in which our earthly paradise generates all this raw wealth.

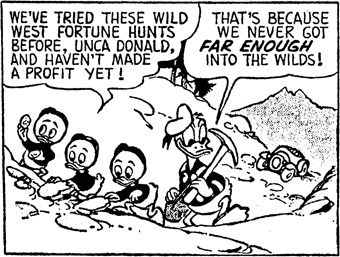

It comes, above all, in the form of hidden treasure. It is to be found in the Third World, and is magically pointed out by some ancient map, a parchment, an inheritance, an arrow, or a clue in a picture. After great adventures and obstacles, and after defeating some thief trying to get there first (disqualified from the prize because it wasn’t his idea, but filched from someone else’s map), the good Duckburgers appropriate the idols, figurines, jewels, crowns, pearls, necklaces, rubies, emeralds, precious daggers, golden helmets, etc.

First of all, we are struck by the antiquity of the coveted object. It has lain buried for thousands of years: within caverns, ruins, pyramids, coffers, sunken ships, Viking tombs, etc.—that is, any place with vestiges of civilized life in the past. Time separates the treasure from its original owners, who have bequeathed this unique heritage to the future. Furthermore, this wealth is left without heirs; despite their total poverty, the noble savages take no interest in the gold abounding so near them (in the sea, in the mountains, beneath the tree, etc.). These ancient civilizations are envisioned, by Disney, to have come to a somewhat catastrophic end. Whole families exterminated, armies in constant defeat, people forever hiding their treasure, for … for whom? Disney conveniently exploits the supposed total destruction of past civilizations in order to carve an abyss between the innocent present-day inhabitants and the previous, but non-ancestral inhabitants. The innocents are not heirs to the past, because that past is not father to the present. It is, at best, the uncle. There is an empty gap. Whoever arrives first with the brilliant idea and the excavating shovel has the right to take the booty back home. The noble savages have no history, and they have forgotten their past, which was never theirs to begin with. By depriving them of their past, Disney destroys their historical memory, in the same way he deprives a child of his parenthood and genealogy, with the same result: the destruction of their ability to see themselves as a product of history.

It would appear, moreover, that these forgotten peoples never actually produced this treasure. They are consistently described as warriors, conquerors, and explorers, as if they had seized it from someone else. In any event, there is no reference at any time—how could there be, with something that happened so long ago?—to the making of these objects, although they must have been handcrafted. The actual origin of the treasure is a mystery which is never even mentioned. The only legitimate owner of the treasure is the person who had the brilliant idea of tracking it down; he creates it the moment he thinks of setting off in search of it. It never really existed before, anywhere. The ancient civilization is the uncle of the object, and the father is the man who gets to keep it. Having discovered it, he rescued it from the oblivion of time.

But even then the object remains in some slight contact with the ancient civilization; it is the last vestige of vanishing faces. So the finder of the treasure has one more step to take. In the vast coffers of Scrooge there is never the slightest trace of the handcrafted object, in spite of the fact that, as we have seen, he brings treasure home from so many expeditions. Only banknotes and coins remain. As soon as the treasure leaves its country of origin for Duckburg, it loses shape, and is swallowed up by Scrooge’s dollars. It is stripped of the last vestige of that crafted form which might link it to persons, places, and time. It turns into gold without the odor of fatherland or history. Uncle Scrooge can bathe, cavort, and plunge in his coins and banknotes (in Disney these are no mere metaphors) more comfortably than in spiky idols and jeweled crowns. Everything is transmuted mechanically (but without machines) into a single monetary mold in which the last breath of human life is extinguished. And finally, the adventure which led to the relic fades away, together with the relic itself. As treasure buried in the earth, it pointed to a past, however remote it may be, and even as treasure in Duckburg (were it to survive in its original form) it would point to the adventure experienced, however remote that may be. Just as the historical memory of the original civilization is blotted out, so is Scrooge’s personal memory of his experience. Either way, history is melted down in the crucible of the dollar. The falsity of all the Disney publicity regarding the educational and aesthetic value of these comics, which are touted as journeys through time and space and aids to the learning of history and geography, etc., stands revealed. For Disney, history exists in order to be demolished, in order to be turned into the dollar which gave it birth and lays it to rest. Disney even kills archeology, the science of artifacts.

Disnification is Dollarfication: all objects (and, as we shall see, actions as well) are transformed into gold. Once this conversion is completed the adventure is over: one cannot go further, for gold, ingot, or dollar bill, cannot be reduced to a more symbolic level. The only prospect is to go hunting for more of the same, since once it is invested it becomes active, and it will start taking sides and enter contemporary history. Better cross it out and start afresh. Add more adventures which accumulate in aimless and sterile fashion.

So it is not surprising that the hoarder desires to skip these productive phases, and go off in search of pure gold.

But even in the treasure hunt the productive process is lacking. On your marks, ready, go, collect; like fruit picked from a tree. The problem lies not in the actual extraction of the treasure, but in discovering its geographical location. Once one has got there, the gold—always in nice fat nuggets—is already in the bag, without having raised a single callous on the hand which carries it off. Mining is like abundant agriculture, once one has had the genius to spot the mine. And agriculture is conceived like picking flowers in an infinite garden. There is no effort in the extraction, it is foreign to the material of which the object is made: bland, soft, and unresistant. The mineral only plays hide and seek. One only needs cunning to lift it from its sanctuary, not physical labor to shape its content and give it form, changing it from its natural physical-mineral state into something useful to human society. In the absence of this process of transformation, wealth is made to appear as if society creates it by means of the spirit, the idea, the little light bulbs flashing over the characters’ heads. Nature apparently delivers the material ready-to-use, as in primitive life, without the intervention of workman and tool. The Duckburgers have airplanes, submarines, radar, helicopters, rockets; but not so much as a stick to open up the earth. “Mother Earth” is prodigal, and taking in the gold is as innocent as breathing in fresh air. Nature feeds gold to these creatures: it is the only sustenance these aurivores desire.

Now we understand why it is that the gold is found yonder in the world of the noble savage. It cannot appear in the city, because the normal order of life is that of production (although we shall see later how Disney eliminates even this factor in the cities). The origin of this wealth has to appear natural and innocent. Let us place the Duckburgers in the great uterus of history: all comes from nature, nothing is produced by man. The child must be taught (and along the way, the adult convince himself) that the objects have no history; they arise by enchantment, and are untouched by human hand. The stork brought the gold. It is the immaculate conception of wealth.

The production process in Disney’s world is natural, not social. And it is magical. All objects arrive on parachutes, are conjured out of hats, are presented as gifts in a non-stop birthday party, and are spread out like mushrooms. Mother earth gives all: pick her fruits, and be rid of guilt. No one is getting hurt.

Gold is produced by some inexplicable, miraculous natural phenomenon. Like rain, wind, snow, waves, an avalanche, a volcano, or like another planet.

“What is that falling from the sky?”

“Hardened raindrops … Ouch! Or molten metal.”

“It can’t be. It’s gold coins. Gold!”

“Hurray! A rain of gold! Just look at that rainbow.”

“We must be having visions, Uncle Scrooge. It can’t be true.”

But it is.

Like bananas, like copper, like tin, like cattle. One sucks the milk of gold from the earth. Gold is claimed from the breast of nature without the mediation of work. The claimants have clearly acquired the rights of ownership thanks to their native genius, or else, thanks to their accumulated suffering (an abstracted form of work, as we explain below).

It is not superhuman magic, like that of the witch Magica de Spell, for example, which creates the gold. This kind of magic, distilled from the demon of technology, is merely a parasite upon nature. Man cannot counterfeit the wealth. He has to get it through some other charmed source, the natural one, in which he does not have to intervene, but only deserve.

Example. Donald and nephews, followed by Magica (TR 111, DD 1/66), search for the rainbow’s end, behind which, according to the legend, is hidden a golden pot, the direct fruit of nature (TR 111, US 38, 6-8/62). Our heroes do not exactly find the mythical treasure, but return with another kind of “pot of gold”: fat commercial profits. How did this happen? Uncle Scrooge’s airplane, loaded with lemon seeds, accidently inseminated the North African desert, and when Magica de Spell provoked a rainstorm, within minutes the whole area became an orchard of lemon trees. The seeds (i.e. ideas) come from abroad, magic or accident sows them, and the useless, underdeveloped desert soil makes them grow. “Come on, boys!” cries Donald, “let’s start picking lemons. And take them to the town to sell.” Work is minimal and a pleasure; the profit is tremendous.

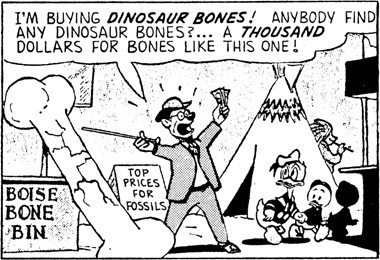

This does not happen only in distant places, but also in Duckburg, on its beaches, woods, and mountains. Donald and Gladstone, for example (D 381, CS 5/59), go on a beachcombing expedition, to see who comes up with the most valuable find to give to Daisy and win her company for lunch. The sea washes up successively, huge seashells, a giant snail, a “very valuable” ancient Indian seashell necklace, rubber boats (one each for Gladstone and Donald), a rubber elephant loaded with tropical fruits, papayas and mangoes, an Alaskan kayak, a mirror, and an ornamental comb. The sea is a cornucopia; generous nature showers abundance upon man, and in the Third World, nature does so in a particularly exotic form. In and beyond Duckburg, it is always nature that mediates between man and wealth.

It is surely undeniable nowadays that all man’s real and concrete achievements derive from his effort and his work. Although nature provides the raw materials, man must struggle to make a living from them. If this were not so, we would still be in Eden.

In the world of Disney, no one has to work in order to produce. There is a constant round of buying, selling, and consuming, but to all appearances, none of the products involved has required any effort whatsoever to make. Nature is the great labor force, producing objects of human and social utility as if they were natural.

The human origin of the product—be it table, house, car, clothing, gold, coffee, wheat, or maize (which, according to TR 96, comes from granaries, direct from warehouses, rather than from the fields)—has been suppressed. The process of production has been eliminated, as has all reference to its genesis; the actors, the objects, the circumstances of the process never existed. What, in fact, has been erased is the paternity of the object, and the possibility to link it to the process of production.

This brings us back to the curious Disney family structure with the absence of natural paternity. The simultaneous lack of direct biological production and direct economic production, is not coincidental. They both coincide and reinforce a dominant ideological structure which also seeks to eliminate the working class, the true producer of objects. And with it, the class struggle.

Disney exorcises history, magically expelling the socially (and biologically) reproductive element, leaving amorphous, rootless, and inoffensive products—without sweat, without blood, without effort, and without the misery which they inevitably sow in the life of the working class. The object produced is truly fantastic; it is purged of unpleasant associations which are relegated to an invisible background of dreary, sordid slumland living. Disney uses the imagination of the child to eradicate all reference to the real world. The products of history which “people” and pervade the world of Disney are incessantly bought and sold. But Disney has appropriated these products and the work which brought them into being, just as the bourgeoisie has appropriated the products and labor of the working class. The situation is an ideal one for the bourgeoisie: they get the product without the workers. Even to the point when on the rare occasion a factory does appear (e.g. a brewery in TR 120) there is never more than one workman who seems to be acting as caretaker. His role appears to be little more than that of a policeman protecting the autonomous and automated factory of his boss. This is the world the bourgeoisie have always dreamed of. One in which a man can amass great wealth, without facing its producer and product: the worker. Objects are cleansed of guilt. It is a world of pure surplus without the slightest suspicion of a worker demanding the slightest reward. The proletariat, born out of the contradictions of the bourgeois regime, sell their labor “freely” to the highest bidder, who transforms the labor into wealth for his own social class. In the Disney world, the proletariat are expelled from the society they created, thus ending all antagonisms, conflicts, class struggle and indeed, the very concept of social class. Disney’s is a world of bourgeois interests with the cracks in the structure repeatedly papered over. In the imaginary realm of Disney, the rosy publicity fantasy of the bourgeoisie is realized to perfection: wealth without wages, deodorant without sweat. Gold becomes a toy, and the characters who play with it are amusing children; after all, the way the world goes, they aren’t doing any harm to anyone … within that world. But in this world there is harm in dreaming and realizing the dream of a particular class, as if it were the dream of the whole of humanity.

There is a term which would be like dynamite to Disney, like a scapulary to a vampire, like electricity convulsing a frog: social class. That is why Disney must publicize his creations as universal, beyond frontiers; they reach all homes, they reach all countries. O immortal Disney, international patrimony, reaching all children everywhere, everywhere, everywhere.

Marx had a word—fetishism—for the process which separates the product (accumulated work) from its origin and expresses it as gold, abstracting it from the actual circumstances of production. It was Marx who discovered that behind his gold and silver, the capitalist conceals the whole process of accumulation which he achieves at the worker’s expense (surplus value). The words “precious metals,” “gold,” and “silver” are used to hide from the worker the fact that he is being robbed, and that the capitalist is no mere accumulator of wealth, but the appropriator of the product of social production. The transformation of the worker’s labor into gold, fools him into believing that it is gold which is the true generator of wealth and source of production.

Gold, in sum, is a fetish, the supreme fetish, and in order for the true origin of wealth to remain concealed, all social relations, all people are fetishized.

Since gold is the actor, director, and producer of this film, humanity is reduced to the level of a thing. Objects possess a life of their own, and humanity controls neither its products nor its own destiny. The Disney universe is proof of the internal coherence of the world ruled by gold, and an exact reflection of the political design it reproduces.

Nature, by taking over human production, makes it evaporate. But the products remain. What for? To be consumed. Of the capitalist process which goes from production to consumption, Disney knows only the second stage. This is consumption rid of the original sin of production, just as the son is rid of the original sin of sex represented by his father, and just as history is rid of the original sin of class and conflict.

Let us look at the social structure in the Disney comic. For example, the professions. In Duckburg, everyone seems to belong to the tertiary sector, that is, those who sell their services: hairdressers, real estate and tourist agencies, salespeople of all kinds (especially shop assistants selling sumptuary objects, and vendors going from door-to-door), nightwatchmen, waiters, delivery boys, and people attached to the entertainment business. These fill the world with objects and more objects, which are never produced, but always purchased. There is a constant repetition of the act of buying. But this mercantile relationship is not limited to the level of objects. Contractual language permeates the most commonplace forms of human intercourse. People see themselves as buying each other’s services, or selling themselves. It is as if the only security were to be found in the language of money. All human interchange is a form of commerce; people are like a purse, an object in a shop window, or coins constantly changing hands.

“It’s a deal,” “‘What the eye doesn’t see…you can take for free’—I should patent that saying.” “You must have spent a fortune on this party, Donald.” These are explicit examples, it is generally implicit that all activity revolves around money, status or the status-giving object, and the competition for them.

The world of Walt, in which every word advertises something or somebody, is under an intense compulsion to consume. The Disney vision can hardly transcend consumerism when it is fixated upon selling itself, along with other merchandise. Sales of the comic are fostered by the so-called “Disneyland Clubs,” which are heavily advertised in the comics, and are financed by commercial firms who offer cut prices to members. The absurd ascent from corporal to general, right up to chief-of-staff, is achieved exclusively through the purchase of Disneyland comics, and sending in the coupons. It offers no benefits, except the incentive to continue buying the magazine. The solidarity which it appears to promote among readers simply traps them in the buying habit.

Surely it is not good for children to be surreptitiously injected with a permanent compulsion to buy objects they don’t need. This is Disney’s sole ethical code: consumption for consumption’s sake. Buy to keep the system going, throw the things away (rarely are objects shown being enjoyed, even in the comic), and buy the same thing, only slightly different, the next day. Let money change hands, and if it ends up fattening the pockets of Disney and his class, so be it.

Disney creatures are engaged in a frantic chase for money. As we are in an amusement world, allow us to describe the land of Disney as a carrousel of consumerism. Money is the goal everyone strives for, because it manages to embody all the qualities of their world. To start with the obvious, its powers of acquisition are unlimited, encompassing the affection of others, security, influence, authority, prestige, travel, vacation, leisure, and to temper the boredom of living, entertainment. The only access to these things is through money, which comes to symbolize the good things of life, all of which can be bought.

But who decides the distribution of wealth in the world of Disney? By what criteria is one placed at the top or the bottom of the pile?

Let us examine some of the mechanisms involved. Geographical distance separates the potential owner, who takes the initiative, from the ready-to-use gold which passively awaits him. But this distance in itself is insufficient to create obstacles and suspense along the way. So a thief after the same treasure, appears on the scene. Chief of the criminal gangs are the Beagle Boys, but there are innumerable other professional crooks, luckless buccaneers, and decrepit eagles, along with the inevitable Black Pete. To these we may add Magica de Spell, Big Bad Wolf, and some lesser thieves of the forest, like Brer Bear and Brer Fox.

They are all oversized, dark, ugly, ill-educated, unshaven, stupid (they never have a good idea), clumsy, dissolute, greedy, conceited (always toadying each other), and unscrupulous. They are lumped together in groups and are individually indistinguishable. The professional crooks, like the Beagle Boys, are conspicuous for their prison identification number and burglar’s mask. Their criminality is innate: “Shut up,” says a cop seizing a Beagle Boy, “you weren’t born to be a guard. Your vocation is jailbird.” (F 57).

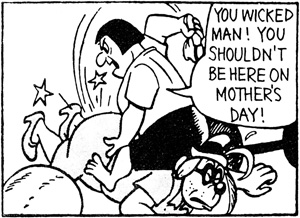

Crime is the only work they know; otherwise, they are slothful unto eternity. Big Bad Wolf (D 281) reads a book all about disguises (printed by Confusion Publishers): “At last I have found the perfect disguise: no one will believe that Big Bad Wolf is capable of working.” So he disguises himself as a worker. With his moustache, hat, overalls, barrow, and pick and shovel, he sees himself as quite the southern convict on a road gang.

As if their criminal record were not sufficient to impress upon us the illegitimacy of their ambitions, they are constantly pursuing the treasure already amassed or pre-empted by others. The Beagle Boys versus Scrooge McDuck are the best example, the others being mere variations on this central theme. In a world so rich in maps and badly kept secrets, it is a statistical improbability and seems unfair that the villains should not occasionally, at least, get hold of a parchment first. Their inability to deserve this good fortune is another indication that there is no question of them changing their status. Their fate is fruitless robbery or intent to rob, constant arrest or constant escape from jail (perhaps there are so many of them that jail can never hold them all?). They are a constant threat to those who had the idea of hunting for gold.

The only obstacle to the adventurer’s getting his treasure is not a very realistic one. The sole purpose of the presence of the villain is to legitimatize the right of the other to appropriate the treasure. Occasionally the adventurer is faced with a moral dilemma: his gold or someone else’s life. He always chooses in favor of the life, although he somehow never has to sacrifice the gold (the choice was not very real, the dice were loaded). But he can at least confront evil temptations, whereas the villains, with a few exceptions, never have a chance to search their conscience, and to rise above their condition.

Disney can conceive of no other threat to wealth than theft. His obsessive need to criminalize any person who infringes the laws of private property, invites us to look at these villains more closely. The darkness of their skin, their ugliness, the disorder of their dress, their stature, their reduction to numerical categories, their mob-like character, and the fact that they are “condemned” in perpetuity, all add up to a stereotypical stigmatization of the boss’s real enemy, the one who truly threatens his property.

But the real life enemy of the wealthy is not the thief. Were there only thieves about him, the man of property could convert history into a struggle between legitimate owners and criminals, who are to be judged according to the property laws he, the owner, has established. But reality is different. The element which truly challenges the legitimacy and necessity of the monopoly of wealth, and is capable of destroying it, is the working class, whose only means of liberation is to liquidate the economic base of the bourgeoisie and abolish private property. Since the moment the bourgeoisie began exploiting the proletariat, the former has tried to reduce the resistance of the latter, and indeed, the class struggle itself, to a battle between good and evil, as Marx showed in his analysis of Eugene Sue’s serial novels.1 The moral label is designed to conceal the root of the conflict, which is economic, and at the same time to censure the actions of the class enemy.

In Disney, the working class has therefore been split into two groups: criminals in the city, and noble savages in the countryside. Since the Disney worldview emasculates violence and social conflicts, even the urban rogues are conceived as naughty children (“boys”). As the anti-model, they are always losing, being spanked, and celebrating their stupid ideas by dancing in circles, hand in hand. They are expressions of the bourgeois desire to portray workers’ organizations as a motley mob of crazies.

Thus, when Scrooge is confronted by the possibility that Donald has taken to thieving (F 178), he says “My nephew, a robber? Before my own eyes? I must call the police and the lunatic asylum. He must have gone mad.” This statement reflects the reduction of criminal activity into a psychopathic disease, rather than the result of social conditioning. The bourgeoisie convert the defects of the working class which are the outcome of their exploitation into moral blemishes, objects of derision and censure, so as to weaken them and to conceal that exploitation. The bourgeoisie even impose their own values upon the ambitions of the enemy, who, incapable of originality, steal in order to become millionaires themselves and join the exploiting class. Never are they depicted as trying to improve society. This caricature of workers, which twists every characteristic capable of lending them dignity and respect, and thereby, identity as a social class, turns them into a spectacle of mockery and contempt. (And parenthetically, in the modern technological era, the daily mass culture diet of the bourgeoisie still consists of the same mythic caricatures which arose during the late nineteenth century machine age).

The criterion for dividing good from bad is honesty, that is, the respect for private property. Thus in “Honesty Rewarded” (D 393, CS 12/45), the nephews find a ten dollar bill and fight for it, calling each other “thief,” “crook,” and “villain.” But Donald intervenes: such a sum, found in the city, must have a legal owner, who must be traced. This is a titanic task, for all the big, ugly, violent, dark-skinned people try to steal the money for themselves. The worst is one who wants to steal the note in order to “buy a pistol to rob the orphanage.” Peace finally returns (significantly, Donald was reading War and Peace in the first scene), when the true owner of the money appears. She is a poor little girl, famished and ragged, the only case of social misery in our entire sample. “This is all my mom had left, and we haven’t eaten all day long.”

Just as the “good” foreigners defended the simple natives of the Third World, now they protect another little native, the underprivileged mite of the big city. The nephews have behaved like saints (they actually wear haloes in the last picture), because they have recognized the right of each and all to possess the money they already own. There is no question of an unjust distribution of wealth: if everyone were like the honest ducklings rather than the ugly cheats, the system would function perfectly. The little girl’s problem is not her poverty, it is having lost the only money her family had (which presumably will last forever, or else they will starve and the whole house of Disney will come tumbling down). To avoid war and preserve social peace, everyone should deliver unto others what is already theirs. The ducklings decline the monetary reward offered by Donald: “We already have our reward. Knowing that we have helped make someone happy.” But the act of charity underlines the moral superiority of the givers and justifies the mansion to which they return after their “good works” in the slums. If they hadn’t returned the banknote, they would have descended to the level of the Beagle Boys, and would not be worthy enough to win the treasure hunt. The path to wealth lies through charity which is a good moral investment. The number of lost children, injured lambs, old ladies needing help to cross the street, is an index of the requirements for entry into the “good guys club”—after one has been already nominated by another “good guy.” In the absence of active virtue, Good Works are the proof of moral superiority.

Prophetically, Alexis de Tocqueville wrote in his Democracy in America, “By this means, a kind of virtuous materialism may ultimately be established in the world, which would not corrupt, but enervate the soul, and noiselessly unbend its springs of action.” It is a pity that the Frenchman who wrote this in the mid-nineteenth century did not live to visit the land of Disney, where his words have been burlesqued in a great idealistic cock-a-doodle-doo.

Thus the winners are announced in advance. In this race for money where all the contestants are apparently in the same position, what is the factor which decides this one wins and the other one loses? If goodness-and-truth are on the side of the “legitimate” owner, how does someone else take ownership of the property?

Nothing could be more simple and more revealing: they can’t. The bad guys (who, remember, behave like children) are bigger, stronger, faster, and armed; the good guys have the advantage of superior intelligence, and use it mercilessly. The bad guys rack their brains desperately for ideas (in D 446, “I have a terrific plan in my head,” says one, scratching it like a half-wit, “Are you sure you have a head, 176–716?”). Their brainlessness is invariably what leads to their downfall. They are caught in a double bind: if they use only their legs, they won’t get there; if they use their heads as well, they won’t get there either. Non-intellectuals by definition, their ideas can never prosper. Thinking won’t do you bad guys any good, better rely on those arms and legs, eh? The little adventurers will always have a better and more brilliant idea, so there’s no point in competing with them. They hold a monopoly on thought, brains, words, and for that matter, on the meaning of the world at large. It’s their world, they have to know it better than you bad guys, right?

There can be only one conclusion: behind good and evil are hidden not only the social antagonists, but also a definition of them in terms of soul versus body, spirit versus matter, brain versus muscle, and intellectual versus manual work. A division of labor which cannot be questioned. The good guys have “cornered the knowledge market” in their competition against the muscle-bound brutes.

But there is more. Since the laboring classes are reduced to legs running for a goal they will never reach, the bearers of ideas are left as the legitimate owners of the treasure. They won in a fair fight. And not only that, it was the power of their ideas which created the wealth to begin with, and inspired the search, and proved, once again, the superiority of mind over matter. Exploitation has been justified, the profits of the past have been legitimized, and ownership is found to confer exclusive rights on the retention and increase of wealth. If the bourgeoisie now control the capital and the means of production, it is not because they exploited anyone or accumulated wealth unfairly.

Disney, throughout his comics, implies that capitalist wealth originated under the same circumstances as he makes it appear in his comics. It was always the ideas of the bourgeoisie which gave them the advantage in the race for success, and nothing else.

And their ideas shall rise up to defend them.