Our very mastery seems to escape our mastery.

—Michel Serres, Conversations on Science, Culture, and Time

In

parts 1 and

2 of this book, I investigated certain portions of the works of Freud, Loewald, and Lacan in order to fashion a drive theory hinted at by all but arrived at by none. In

part 3 that drive theory was both historically situated and further developed in dialogue with Adorno, Horkheimer, and Marcuse. I would like finally to drop the scaffolding and guide the reader along the contours of the new edifice.

With a great deal of help from Loewald, I have argued here that the death drive is best understood as a drive against self-individuation to recreate the kind of care structure characteristic of early life in which self/other boundaries are fluid. The aim of the death drive, put otherwise, is

not to be ourselves, to annul the fact that we are separate individuals. This separateness is made particularly harsh in early life by the total and terrifying dependence on the “other”—the other of what I have called the tension-within position, a position wherein infants feel themselves to be one component of a more global situation that includes the “other” in it. One might object that

death is not really the right word for that toward which the infant strives (Loewald himself calls it union), and this is no doubt true in the sense that the infant has not an inkling of what death really means for adults (but, then, the same goes for love and murder as well). It needs to be emphasized, nonetheless, that it is an

end of one’

s existence as a separate individual that is desired and thus that the death drive is, in this sense, a perfectly apposite phrase.

So if I am born as a creature that does not wish to be itself, how do I grow to become self-interested, to become someone who cares and strives for individuality? For Loewald, the first step in this direction lies with a peculiar manifestation of the death drive that comes to resist the death drive itself: the infant wants so immoderately to keep intact the primordial density that, even when the parent is absent, the child fabricates parental presence in fantasy—a process termed “identification.” “I may not share a world with this much-needed ‘other,’ but I can directly be the ‘other,’ and thus not be myself in fantasy when I am forced to reckon with myself in reality.”

While this imitation is, in itself, only an instantiation of the death drive, it also serves as the foundation of a process of mourning: the fantasy may shatter with little force, but it serves its purpose if it has mitigated even slightly the pain of absence, if it has provided a “presence in absence.” Over time, identifications are made and remade, only to fail and fail again, but the effort is not for nothing, as those identifications never really disappear but rather quietly morph into internalizations, into pieces of the infant’s own growing psychic structures. In other words, the fantasy “I am the ‘other’” is paradoxically the source of the subject that is posited within it; having been the “other,” the “other” comes to be one part of me. Which might also be to say: I will always be my parents, at least in part.

The “I” may only be a precipitate of various past identifications, but it nonetheless, in its emerging cohesiveness, comes to be a source of some pride. “I can do this. I prefer that. And, most importantly, I, unlike others, never leave myself.” This is not to say that the infant has yet achieved anything like independence, only that a tension has begun to grow between the demand to cultivate a growing independence and the still frequent need for union; in other words, between the ego and the id, between the drive to mastery and the death drive.

Caretakers must inevitably suffer under the weight of these contradictory imperatives, and in a very particular way. Their efforts come to be seen in a schizoid manner: on the one hand, they are the sources of nurture and care, the other half in the primordial bond. On the other, they threaten engulfment of the prized and fledgling ego. The pull of the tension-within position is too strong, and the “I” simultaneously wishes and fears to be swept away in it. This fundamental and inevitable conflict is what Freud gendered in naming the Oedipus complex: mother as bond, father as separation. While, at certain points in history, this gendering of the conflict resonated with familial reality, the conflict itself only seizes upon gender divisions and does not depend on them.

1It is tempting, with Loewald, to make sense of

aggression in terms of disappointment: by separating from my parents, I “kill” them—or at least their early psychic representatives. But there is another possibility implied within his model, which I developed with help from Jacques Lacan in

chapter 3: if parents are the objects of a schizoid projection—that is, seen by the child as both caring and engulfing—and they are

also the primary objects of identification, the projection must invariably feed back into the identification. In other words, children come to attempt to

engulf others, to express an

omnipotence over them, because they themselves have felt engulfed in the same way: “identification with the aggressor,” only with the twist that the aggressor need not be what we would consider a real aggressor. This is to deny neither that children often suffer under

actual aggression nor that that aggression shapes development. When children lash out, and they are met not with patience and a capacity for what Wilfred Bion calls “reverie” but rather with an equally or excessively strong and violent force, their belief that their parents threaten the ego is confirmed rather than disproven.

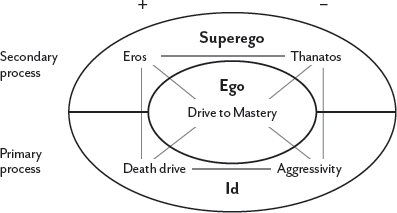

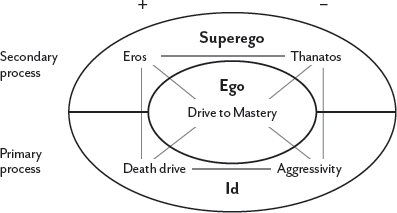

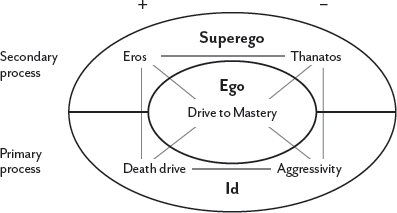

In sum, the death drive, the drive to mastery, and aggressivity are the three drives that govern preoedipal life, and their contradictory demands force the child to the oedipal breaking point. The great solution to this crisis, for both Loewald and Lacan, lies with language. In my capacity to speak and communicate, I find the possibility of partially satisfying the demand to break down my own ego boundaries—namely, by pushing beyond my present reality through a reconnection of “words” and “things”—in such a way that the conflict between this demand and those of the ego is transformed into the more manageable tension between ego and superego. Put differently, the ego reconciles with the id by finding a place for it within itself.

The death drive is not, however, the only preoedipal force that finds sublimated expression in the superego. Especially if it has not been skillfully managed with parental “reverie,” aggressivity—the drive to engulf the other into nothingness—imposes itself by joining the death drive in attaching itself to language. Whereas the sublimated expression of the latter (I have called this

Eros) pushes the ego beyond itself, having transformed a drive to ego destruction into one of ego transcendence, the sublimated expression of the former (

Thanatos) moves in the opposite direction, insulating the ego further and further from destabilizing otherness.

I have been unable to resist the temptation to depict the final stage of this developmental sequence as a figure. Like all visual representations, it veils as much as it reveals, but hopefully some light is shed on the relations between the different elements upon which I have been working.

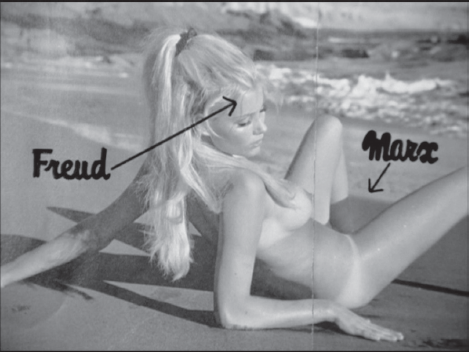

Though I have remained homed in on a psychoanalytic logic throughout, the concern driving this project—namely, how precisely we ought to understand the particular manner in which subjects in late capitalism are alienated—stems from critical social theory. One might say that, for this book, Freud is the secondary process, Marx the primary (an idea so strikingly depicted in the famous image from Jean-Luc Godard’s

Le Gai Savoir included here).

2 In

chapters 4 and

5 I turned to the Frankfurt school’s shared belief that they were witnessing a fundamental change in the psyche that somehow simultaneously weakened and strengthened the force of the superego. I have made sense of this theory of psychic transformation in claiming that a) Eros’s sway over the superego is weakened by the direct death drive gratification provided by the products of the culture industry and b) Thanatos’s claim on the superego is strengthened by the aggressive sublimation involved in technological advance.

3 Certainly the energetic sapping of Eros and emboldening of Thanatos makes for no rosy prospects, but it does, as I argued in

chapter 4, open a distinct possibility of resistance for late capitalist subjects: freed from the strict moral codes of bourgeois individualism, it becomes possible to assess the nature and the function of the superego and redeploy this function on our own terms. In a short paper published in the same year as

The Future of an Illusion, Freud admitted that “we have still a great deal to learn about the nature of the super-ego.”

4 I understand this claim in the imperative.

FIGURE C.1. Completed figure.

Where’s the Sex?

Like Freud’s metapsychology papers, the psychoanalytically focused chapters of this book have been dense and formal, and one might wonder what happened to that ethereal and unceremonious rudiment of psychoanalytic theory: sexuality. I have not, of course, managed completely to eliminate sexuality: orality is so closely tied to fantasies of engulfment and anality to the activity of mastery that this book could well be rewritten as The Mouth and the Anus. It is true, nonetheless, that I have somewhat methodically avoided the sexual, and it behooves me to offer some evidence that repression is not at work (or, at least, that repression is at work in an interesting way).

FIGURE C.2. From Jean-Luc Godard’s Le Gai Savoir.

In Freud, sexuality is a notoriously slippery term. For my present purposes, I take it to pertain to the variety of pleasures that one can experience with one’s body, and I take its importance to derive from the limitations imposed on those pleasures in the course of maturation.

5 In the introduction I argued that the kinds of bodies that we have play an important role in the formation of drives,

6 but I did not “flesh” out this claim a) because the book is focused on the developmental logic in which drives themselves are formed and transformed and b) because I understand the question of how that developmental logic is both informed by our bodily capacities and experienced at a bodily level to be one that deserves a book of its own, one that I hope to write as an unwieldy addendum to

Death and Mastery. Whereas the present book deals with the difficult journey from utter dependence to partial independence (and its implications for the historically specific people that we are), the next one will confront a different but related problem—namely, the kinds of bodies that we have and what we do with them. For better or worse, then, I have chosen to uphold Freud’s distinction between metapsychological theory, which exists at a level of abstraction from psychoanalytic experience, and the nonmetapsychological psychoanalytic theory rooted in close observation (though between these two levels there is undoubtedly some conceptual bleed).

Part of the reason I find it necessary to relegate the whole question of sexuality to a separate book is that I believe psychoanalytic theory since Freud has generally shied away from investigating the body as Freud himself did, for a variety of reasons: the swift reification of the “oral, anal, genital” triad, which immediately opened the question of erogenous zones to caricature; the desire of emigrant analysts for a scientific respectability naturally threatened by too much speculation about cloaca and the like; the focus on speech and language, rather than the body, as the locus of analytic knowledge. For a similarly strange confluence of altogether different reasons, including the twin influence of phenomenology and neuroscience and the realization that psychoanalytic theory has privileged the relational aspects of therapeutic work to the neglect of others, the body has increasingly become a topic of interest for contemporary psychoanalysts, but the body that has “returned” to analytic theory is not the body in which I am interested.

This body is not the body that reveals the affective attunements of the intersubjectivists, nor is it the body that is the seat of an expanded conception of sensation (as in Leo Bersani’s proposed “soma-analysis”).

7 It is rather the body that has feet, a neck, hair, blood, and, yes, a mouth, an anus, and genitals; it is the body composed of parts the pleasures, significances, and possibilities of which transcend their functions. It is this body that I hope to investigate in a future work.

Administration Today

In the conclusion of

One-Dimensional Man Marcuse poses a question that could very well serve as

the fundamental question of critical theory: “how can administered individuals who have made their mutilation into their own liberties and satisfactions, and thus reproduce it on an enlarged scale—liberate themselves

from themselves as well as from their masters?”

8 As Claus Offe rightly notes, Marcuse identifies here “a dilemma that he himself cannot overcome.”

9 I have attempted in

chapter 4 to make some advance in this regard by articulating a model of liberation from one’s own ego latent in Adorno and Horkheimer’s theorization of a crisis of internalization, though it would obviously be laughable to claim that any resolution on this matter has been achieved.

An even more basic question, however, confronts us today: where do we see the

need for this self-liberation? Marcuse thought signs of general discontent abounded, both “in the ‘catalyst groups’ of the counter-culture (the student movement, women’s movement, in grass roots democracy, etc.), but also in the working class itself: spontaneous sabotage, absenteeism, the demand to reduce the working day.”

10 Where today, by contrast, do we see evinced the need to overcome not simply the egregious dictators and profiteers of the world but the performance principle itself?

Contrary to those who would argue that the impetus for critical theory has disappeared with the adaptation of the individual to the structures and strictures of late capitalism, I believe this need is as evident as in Marcuse’s times, though the increasing strategic adroitness of administrative society has turned the evidence from positive to negative. One finds alienation today not only in protest but also in the great triad of industries devoted to subduing human explosiveness in late capitalist society: the culture industry, the technology industry, and the psychopharmaceutical industry (the last of these, though untreated in this book, has been lurking in the background throughout). What better evidence could there be of the general alienation of the vast majority of subjects than that, in order to devote most of their time to performing preestablished functions for apparatuses they do not control and to existing disconnectedly alongside positively displeasing people, they do not simply want but

need to lose themselves in flickering images, to possess the latest devices, and to adjust their neurochemical balances? In this, Marcuse was absolutely right that the absence of these industries “would plunge the individual into a traumatic void,” being far more psychically “unbearable” than the possibility of “radioactive fallout.”

11It is incorrect to conclude, however, that late capitalist society is therefore

incompatible with human drives, given that that society is constantly doing a great deal to pacify and manage our instinctual lives. Individual and society can actually be fairly well reconciled in late capitalist society, though not in the way we would like. Furthermore, dissatisfaction with that administered reconciliation is most certainly no source of resistance: I can perfectly well know that I am anesthetizing myself to a world that creates ego rigidity through direct death drive gratification or aggressive sublimation while quite happily enjoying my “heart-warmers in the commercial cold.”

12 As I argued in

chapter 4, there are historically specific

possibilities for resistance today, but they are only possibilities—and, furthermore, possibilities that are opened up by the same developments that threaten to close them off forever.

I thus cannot claim to have done anything here to ameliorate the pessimism of the first-generation critical theorists, but then I do not believe that it is something that needs to be ameliorated.

13 Whenever I hear mention of this common characterization of the Frankfurt school, I cannot help but feel that theories are not being faulted in such a way as to overcome pessimism, but rather that the need to overcome pessimism is fueling a desire to find faulty logics.

14 Indeed, this is the only way I can make sense of claims about the culture industry thesis or the theory of technological rationality being wrong or dated at a time when the commodification of culture and obedience to blind instrumentalism are so pervasive as to be invisible in their obviousness.

15Although I am certainly open to Shane Gunster’s claim that “deep pessimism offers a necessary first step in building a visceral awareness that culture need not be the way it is today,” I am not making a claim about the value of pessimism, only affirming Freud’s plea that we not confuse the disagreeable and the untrue.

16 The triumphant procession of Thanatos is indeed quite worrisome, but we should not cover over the problem with repressively confident assertions of theoretical progress. “Eternal Eros” still has a fighting chance “in the struggle with his equally immortal adversary,” but not if we blind ourselves to the power of that adversary.

17