THE COMMERCIAL VALUE OF IMPERIALISM

THE absorption of so large a proportion of public interest, energy, blood and money in seeking to procure colonial possessions and foreign markets would seem to indicate that Great Britain obtained her chief livelihood by external trade. Now this was not the case. Large as was our foreign and colonial trade in volume and in value, essential as was much of it to our national well-being, nevertheless it furnished a small proportion of the total industry of the nation.

According to the conjectural estimate of the Board of Trade “the proportion of the total labour of the British working classes which was concerned with the production of commodities for export (including the making of the instruments of this production and their transport to the ports) was between one-fifth and one-sixth of the whole.”1

If we suppose the profits, salaries, etc., in connexion with export trade to be at the same level with those derived from home trade, we may conclude that between one-fifth and one-sixth of the income of the nation comes from the production and carriage of goods for export trade.

Taking the higher estimate of the magnitude of foreign trade, we should conclude that it furnished employment to one-fifth of our industrial factors, the other four-fifths being employed in supplying home markets.

But this must not be taken as a measure of the net value of foreign trade to our nation, or of the amount of loss that would have been sustained by a diminution of our foreign markets. We are not entitled to assume that a tariff-policy or some other restrictive policy on the part of foreign nations which gradually reduced our export trade would imply an equivalent loss of national income, and of employment of capital and labour in Great Britain. The assumption, sometimes made, that home demand is a fixed amount, and that any commodities made in excess of this amount must find a foreign market, or remain unsold, is quite unwarranted. There is no necessary limit to the quantity of capital and labour that can be employed in supplying the home markets, provided the effective demand for the goods that are produced is so distributed that every increase of production stimulates a corresponding increase of consumption.

Under such conditions a gradual loss of foreign markets would drive more capital and labour into industries supplying home markets; the goods this capital and labour produced would be sold and consumed at home. Under such circumstances some loss would normally be sustained, because it could be reasonably assumed that the foreign market that was lost was a more profitable one than the new home market which took its place; but that loss would certainly be much smaller than the aggregate of the value of trade thus transferred; it would, in fact, be measured by the reduction in profit, and perhaps in wages, attending the substitution of a less remunerative home market for a more remunerative foreign market.

This argument, of course, does not imply that Great Britain could dispense with her external markets, and be no great sufferer in trade and income. Some considerable foreign markets, as we know, are an economic necessity to her, in order that by her exports she may purchase foods and materials which she cannot produce, or can only produce at a great disadvantage.

This fact makes a considerable external market a matter of vital importance to us. But outside the limit of this practical necessity the value of our foreign markets must rightly be considered to be measured, not by the aggregate value of the goods we sell abroad, but by the superior gain from selling them abroad as compared with selling them (or corresponding quantities of other goods) at home. To assume that if these goods are not sold abroad, neither they nor their substitutes could be sold, even at lower prices, in the home market, is quite unwarranted. There is no natural and necessary limit to the proportion of the national product which can be sold and consumed at home. It is, of course, preferable to sell goods abroad where higher profit can be got by doing so, but the net gain to national industry and income must be measured not by the value of the trade done, but by its more profitable nature.

These reflections are required to make us realize (1) that the importance of external trade is not rightly measured by the proportion its volume and value bear at any given time to those of home trade; and (2) that it is by no means essential to the industrial progress of a nation that her external trade should under all conditions keep pace with her home trade.

When a modern nation has attained a high level of development in those industrial arts which are engaged in supplying the first physical necessaries and conveniences of the population, an increasing proportion of her productive energies will begin to pass into higher kinds of industry, into the transport services, into distribution, and into professional, official and personal services, which produce goods and services less adapted on the whole for international trade than those simpler goods which go to build the lower stages of a civilization.1 If this is true, it would appear that, whereas up to a certain point in the development of national life foreign trade will grow rapidly, after that point a decline, not in absolute size or growth but in relative size and growth, will take place.

Figures for the years 1910–1934 are given in the Appendix, p. 370.

There is some reason to hold that Great Britain had, in 1905, reached an industrial level where external trade, though still important, will be relatively less important in her national economy.

Between 1870 and 1900, as the above table shows, the value of our foreign trade had not grown so fast as our population. Whereas upon the generally accepted estimate the growth of the income of the nation during these three decades was from about £1,200,000,000 to £1,750,000,000, yielding an increase of about 10 per cent, in the income per head of the population, the value of foreign trade per head had positively shrunk.

Although the real increase in volume of external trade was considerable when the general fall of prices after 1870 is taken into account, it remains quite evident that neither volume nor value of external trade had kept pace during this period with volume and value of internal trade.1

Next, let us inquire whether the vast outlay of energy and money upon imperial expansion was attended by a growing trade within the Empire as compared with foreign trade. In other words, does the policy tend to make us more and more an economically self-sufficing Empire? Does trade follow the flag?

The figures in the table facing represent the proportion which our trade with our colonies and possessions bears to our foreign trade during the last half of the nineteenth century.

A longer period is here taken as a basis of comparison in order to bring out clearly the central truth, viz., that Imperialism had no appreciable influence whatever on the determination of our external trade until the protective and preferential measures taken during and after the Great War. Setting aside the abnormal increase of exports to our colonies in 1900–1903 due to the Boer War, we perceive that the proportions of our external trade had changed very little during the half century; colonial imports slightly fell, colonial exports slightly rose, during the last decade, as compared with the beginning of the period. Although since 1870 such vast additions have been made to British possessions, involving a corresponding reduction of the area of “Foreign Countries,” this imperial expansion was attended by no increase in the proportions of intraimperial trade as represented in the imports and exports of Great Britain during the nineteenth century.

PERCENTAGES OF TOTAL VALUES.

Annual Averages. |

Imports into Great Britain from |

Exports from Great Britain to |

||

Foreign Countries. |

British Possessions. |

Foreign Countries. |

British Possessions. |

|

1855–1859 |

76.5 |

23.5 |

68–5 |

31.5 |

1860–1864 |

71.1 |

28.8 |

66.6 |

33.4 |

1865–1869 |

76.0 |

24.0 |

72.4 |

27.6 |

1870–1874 |

78.0 |

22.0 |

74.4 |

25.6 |

1875–1879 |

77.9 |

22.1 |

67.0 |

33.0 |

1880–1884 |

76.5 |

23.5 |

65.5 |

34.5 |

1885–1889 |

77.1 |

22.9 |

65.0 |

35.0 |

1890–1894 |

77.1 |

22.9 |

66.5 |

33.5 |

1895–1899 |

78.4 |

21.6 |

66.0 |

34.0 |

1900–1903 |

77.3 |

20.7 |

63.0 |

37.0 |

This table (Cd. 1761 p. 407) refers to merchandise only, excluding bullion. From the export trade, ships and boats (not recorded prior to 1897) are excluded. In exports British produce alone is included. Figures for the years up to 1934 are given in the Appendix, p. 371.

From the standpoint of the recent history of British trade there is no support for the dogma that “Trade follows the Flag.” So far we have examined the question from the point of view of Great Britain. But if we examine the commercial connexion between Great Britain and the colonies from the colonial standpoint, asking whether the external trade of our colonies tends to a closer union with the mother country what result do we reach?

The elaborate statistical investigation of Professor Alleyne Ireland into the trade of our colonial possessions strikes a still heavier blow at the notion that trade follows the flag. Taking the same period, he establishes the following two facts :—

“The total import trade of all the British colonies and possessions has increased at a much greater rate than the imports from the United Kingdom.” “The total exports of all the British colonies and possessions have increased at a much greater rate than the exports to the United Kingdom.”1

The following table2 shows the gradual decline in the importance to the colonies of the commercial connexion with Great Britain since 1872–75, as illustrated in the proportion borne in the value of their exports from and their imports to Great Britain as compared with the value of the total imports and exports of the British colonies and possessions :—1

Four-Yearly Averages. |

Percentages of Imports into Colonies, &c., from Great Britain. |

Percentages of Exports from Colonies, &c., into Great Britain. |

1856–1859 |

46.5 |

57.1 |

1860–1863 |

41.0 |

65.4 |

1864–1867 |

38.9 |

57.6 |

1868–1871 |

39.8 |

53.5 |

1872–1875 |

43.6 |

54.0 |

1876–1879 |

41.7 |

50.3 |

1880–1883 |

42.8 |

48.1 |

1884–1887 |

38.5 |

43.0 |

1888–1891 |

36.3 |

39.7 |

1892–1895 |

32.4 |

36.6 |

1896–1899 |

32.5 |

34.9 |

In other words, while Great Britain’s dependence on her Empire for trade was stationary, the dependence of her Empire upon her for trade was rapidly diminishing.

The actual condition of British trade with foreign countries and with the chief groups of the colonies respectively may be indicated by the following statement1 for the year ending December, 1901 :—

Imports from. |

Exports to. |

|||

Value. |

Percentage. |

Value. |

Percentage. |

|

£ |

£ |

|||

Foreign Countries |

417,615,000 |

80 |

178,450,000 |

|

British India |

38,001,000 |

7 |

39,753,000 |

14 |

Australasia |

34,682,000 |

7 |

26,932,000 |

|

Canada |

19,775,000 |

4 |

7,797,000 |

3 |

British South Africa |

5,155,000 |

1 |

17,006,000 |

6 |

Other British Possessions |

7,082,000 |

1 |

10,561,000 |

4 |

Total |

522,310,000 |

100 |

280,499,000 |

100 |

It is thus clearly seen that while imperial expansion was attended by no increase in the value of our trade with our colonies and dependencies, a considerable increase in the value of our trade with foreign nations had taken place. Did space permit, it could be shown that the greatest increase of our foreign trade was with that group of industrial nations whom we regard as our industrial enemies, and whose political enmity we were in danger of arousing by our policy of expansion—France, Germany, Russia, and the United States.

One more point of supreme significance in its bearing on the new Imperialism remains. We have already drawn attention to the radical distinction between genuine colonialism and Imperialism. This distinction is strongly marked in the statistics of the progress of our commerce with our foreign possessions.

The results of an elaborate investigation by Professor Flux1 into the size of our trade respectively with India, the self-governing colonies and the other colonies may be presented in the following simple table :—2

Percentages of imports from Great Britain. |

Percentage of Exports to Great Britain. |

|||

1867–71. |

1892–96. |

1867–71. |

1892–96. |

|

India |

69.2 |

71.9 |

52.6 |

33.2 |

Self-governing Colonies |

57.5 |

59.2 |

55.4 |

70.3 |

Other Colonies |

34.3 |

26.4 |

46.4 |

29.3 |

Professor Flux thus summarises the chief results of his comparisons : “The great source of growth of Britain’s colonial trade is very clearly shown to be the growth of trade with the colonies to which self-government has been granted. Their foreign trade has nearly doubled, and the proportion of it which is carried on with the mother country has increased from about  per cent, to 65 per cent.

per cent, to 65 per cent.

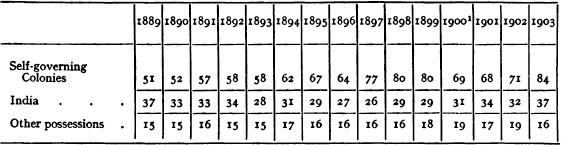

Later statistics3 distinguishing British trade with India, the self-governing colonies and other colonies and possessions impress the same lesson from the standpoint of Great Britain in an even more striking manner.

VALUE OF IMPORTS INTO GREAT BRITAIN FROM THE SEVERAL PARTS OF THE EMPIRE (000,000 OMITTED).

1 Fall-off in imports from self-governing colonies 1900–2 is due entirely to stoppage in gold imports from South Africa.

VALUE OF EXPORTS FROM GREAT BRITAIN INTO THE SEVERAL PARTS OF THE EMPIRE

These tables show that whereas the import and the export trade with our self-governing colonies exhibited a large advance, our import trade alike with India and the “other possessions” was virtually stagnant, while our export trade with these two parts shows a very slight and very irregular tendency to increase.

Now the significance of these results for the study of modern Imperialism consists in the fact that the whole trend of this movement was directed to the acquisition of lands and populations belonging not to the self-governing order but to the “other possessions.” Our expansion was almost wholly concerned with the acquisition of tropical and sub-tropical countries peopled by races to whom we have no serious intention of giving self-government. With the exception of the Transvaal and the Orange River Colony, none of our acquisitions since 1870 belonged, even prospectively, to the self-governing group, and even in the case of the two South African states, the prospective self-government was confined to a white minority of the population. The distinctive feature of modern Imperialism, from the commercial standpoint, is that it adds to our empire tropical and sub-tropical regions with which our trade is small, precarious and unprogressive.

The only considerable increase of our import trade since 1884 is from our genuine colonies in Australasia, North America, and Cape Colony; the trade with India has been stagnant, while that with our tropical colonies in Africa and the West Indies has been in most cases irregular and dwindling. Our export trade exhibits the same general character, save that Australia and Canada show a growing resolution to release themselves from dependence upon British manufactures; the trade with the tropical colonies, though exhibiting some increase, is very small and very fluctuating.

As for the territories acquired under the new Imperialism, except in one instance, no serious attempt to regard them as satisfactory business assets is possible.

The following table (page 39) gives the official figures of the value of our import and export trade with our tropical and sub-tropical possessions for the beginning of the present century. Bullion and specie are included in both accounts.

The entire volume of our export trade with our new protectorates in Africa, Asia and the Pacific amounted to not more than some nine millions sterling, of which more than six millions took place with the Malay Protected States, and was largely through traffic with the Far East. The entire volume of the import trade consisted of about eight millions sterling, half of which is with the same Malay States. At whatever figure we estimate the profits in this trade, it forms an utterly insignificant part of our national income, while the expenses connected directly and indirectly with the acquisition, administration and defence of these possessions must swallow an immeasurably larger sum.

British Trade with New Possessions.1 |

Imports from |

Exports to |

£ |

£ |

|

Cyprus |

83,842 |

132,445 |

Zanzibar Protectorate |

114,088 |

88,777 |

British East Africa Protectorate (including Uganda) |

123,006 |

17,274 |

Somaliland |

389,4242 |

333,8422 |

Southern Nigeria Protectorate |

1,228,959 |

922,657 |

Northern Nigeria Protectorate |

240,110 |

68,442 |

Lagos |

641,203 |

366,171 |

Gambia |

142,560 |

15,158 |

British North Borneo |

275,000 |

368,000 |

Malay Protected States |

4,100,000 |

6,211,000 |

Fiji |

30.567 |

10,161 |

British Solomon Islands Protectorate |

— |

32,203 |

Gilbert and Ellice Islands Protectorate |

20.359 |

21,502 |

British New Guinea |

— |

62,891 |

Leeward Islands |

168,700 |

67,178 |

Windward Islands |

739,095 |

305,224 |

Apart from its quantity, the quality of the new tropical export trade was of the lowest, consisting for the most part, as the analysis of the Colonial Office shows, of the cheapest textile goods of Lancashire, the cheapest metal goods of Birmingham and Sheffield, and large quantities of gunpowder, spirits, and tobacco.

Such evidence leads to the following conclusions bearing upon the economics of the new Imperialism. First, the external trade of Great Britain bore a small and diminishing proportion to its internal industry and trade. Secondly, of the external trade, that with British possessions bore a diminishing proportion to that with foreign countries. Thirdly, of the trade with British possessions the tropical trade, and in particular the trade with the new tropical possessions, was the smallest, least progressive, and most fluctuating in quantity, while it is lowest in the character of the goods which it embraces.

1 Cd. 1761, p. 361.

1 See Contemporary Review, August, 1905, in which the author illustrates this tendency by the statistics of occupations in various nations.

1 The four years subsequent to 1899 show a considerable increase in value of foreign trade, the average value per head for 1900–1903 working out at £21 2s. 5d. But this is abnormal, due partly to special colonial and foreign expenditure in connexion with the Boer War, partly to the general rise of prices as compared with the earlier level.

1 Tropical Colonization, Page 125.

2 Founded on the tables of Professor Ireland (Tropical Colonization, pp. 98–101), and revised up to date from figures in the Statistical Abstract of Colonial Possessions, Cd. 307.

1 Figures for the years 1913–4, 1924–9, 1933–4 are given in the Appendix, pp. 372–3.

1 “Cobden Club Leaflet,” 123, by Harold Cox. Figures for the year 1934–5 are given in the Appendix, p. 371

1 “The Flag and Trade,” Journal of Statistical Society, September, 1899. Vol. lxii, pp. 496–98.

2 Figures for the years 1913–4, 1924–9 and 1933–4 are given in the Appendix, p. 371.

3 Statistical Abstract for the British Empire from 1889 to 1903. (Cd. 2395 pp. 25–28). Full tables of the Export and Import trade of Great Britain with the several parts of the Empire for the years 1904 to 1934, are given in the Appendix, pp. 372–3.

1 Cd. 2395 and Cd. 2337.

2 Trade with British possessions as well as with Great Britain is here included.