CHAPTER ELEVEN FILM MUSIC FOR AN AUTUMN NIGHT

Later that afternoon, Malarkey sits on one of the many Citrus City College benches, trying to grade papers. Malarkey often does that. Finds an empty bench and grades papers since it relieves him of the iteration of climbing the stairs to his office, unlocking the door, opening the door, closing the door, sitting at his desk, turning on the computer, waiting for the computer to upload, logging in, accepting the contract that under penalty of death he will not use the computer for nefarious or pornographic purposes, pledging his allegiance to Citrus City College for the rest of his life, agreeing to never protest for union representation, swearing that he is a citizen (naturalized or otherwise) of the United States, promising to say the Pledge of Allegiance before every class, and to read the US Constitution every night ad absurdum. The Reader gets the idea. The habit of securing a secluded bench on which to work goes back to Malarkey’s Oxford days when he’d walk to a park near Picked Mead off the High Bridge and work on his dissertation with the only distraction being the gurgling of the River Cherwell or, perhaps, the splashing of some wayward punter. Other than that, relative peace and quiet.

But today, the bench he ordinarily prefers to sit on, which is a place of peace and little distraction is not, because on this particular day it is sorority rush day and the gaggle of gurgling young gals are frenetically dancing and posturing in their designer best in order to impress the colloquy of birds that are the sorority actives. Or so he was told. Potential Pi Phis, comely Kappas, delectable DGs all abound and that cacophony of giggling chaos makes grading papers impossible for Malarkey.

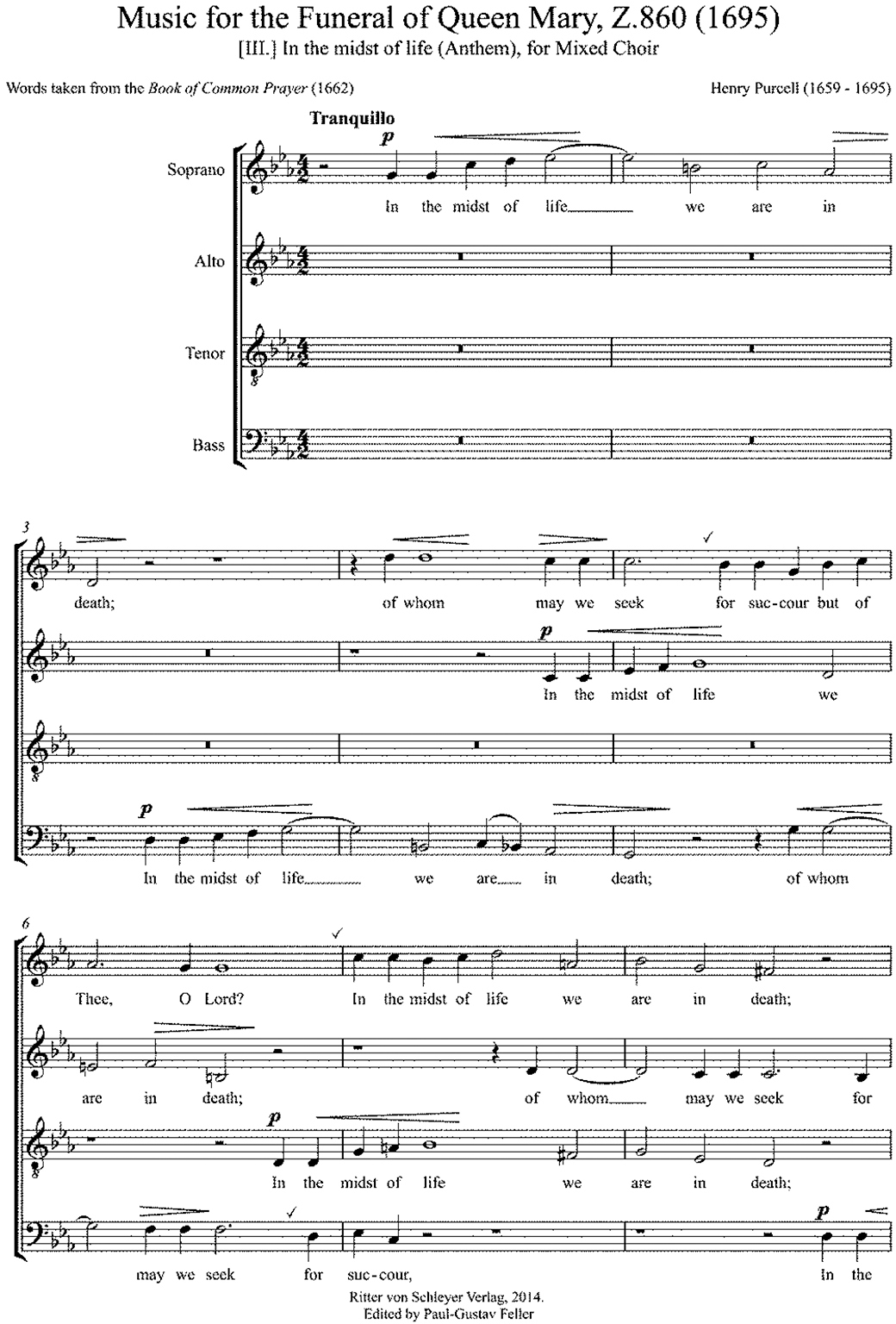

Fortunately, at that precise moment, when he is about to give up, his mobile phone tantalizes him with the sound of Henry Purcell’s “Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary” indicating he has a text message. Just why and when Malarkey chose Purcell’s “Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary” to be his ring tone even Malarkey doesn’t remember, but somehow it has remained in his psyche for years and years. Malarkey tries to trace it back to some incident in his life (a funeral, perhaps), but his best guess is something happened around 1971 that remains in the recesses of his amygdala or hippocampus, but he can’t remember which. If the Reader is not familiar with Purcell’s “Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary” you can Google it and listen to it online as you read this chapter or you can read the sheet music and try to reproduce the music yourself or you can do both. Either way, Malarkey’s cell phone sounds off with something like the following from Purcell’s “Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary.”

Malarkey gazes at the text message which is from Liliana and which reads:

Concert at Disney Hall tonight. You wanna go?

Malarkey being Malarkey responds the only way Malarkey knows how to respond:

WHO’S PAYING?

Apparently, Liliana knows Malarkey even better than Malarkey knows himself and responds:

I am.

To which Malarkey responds the only way Malarkey knows how to respond:

Count me in!

Unfortunately, Malarkey is “emoji challenged” and can’t quite come up with an appropriate emoji to use even though he peruses dozens of available emoji from which to choose in order to let Liliana know that he’s “current” and keen on the idea she’s offered. Why Malarkey sees the need even to use an emoji is beyond his ability to reason precisely because he’s emoji challenged, but he uses it anyway.

Regardless, later that night Malarkey and Liliana arrive at the Walt Disney Concert Hall and the two of them stroll into the Gehry, her arm looped in his, and take their seats: Front Orchestra, Row 131. Liliana spares no expense. Excellent seats to view and hear, but the downside is the seats are so tightly tucked together there’s little room to stretch his legs which aggravates Malarkey’s arthritic knee, which his internist has said sooner or later needs to be replaced, along with the arthritic hip. Not to mention a possible spinal fusion. But grateful to Liliana for the seats and even more grateful for her company, Malarkey does something totally foreign to him: he doesn’t complain. Not complaining is a new behavior for Malarkey, which can only be attributed to one of two things: (1) divine intervention or (2) Liliana’s company. Not being a very religious person, Malarkey believes, and quite rightly, it’s due to the latter.

As the musicians tune up, they await the appearance of the maestro, Gustavo Dudamel, who will conduct the L.A. Philharmonic’s evening performance, “Music from the Movies.” For Malarkey, this isn’t just a “date” since dates don’t come that frequently for Malarkey, especially dates with beautiful women, and Liliana is a very beautiful woman especially this night what with the skimpy black dress thing going on, with the black scarf and tassels around her throat, the black stiletto heels, the revealing décolletage and the scent of just being a woman, a scent Malarkey thinks he lost long ago and far away. Malarkey is dressed in his finest concert attire: his only white, Chambray shirt (recently dry-cleaned) with buttons; a medium-width tie, which due to its width can never go out of style; a blue pinstripe Armani sport coat he bought at the local Citrus City Goodwill store; a pair of freshly washed denims (not to be confused with jeans); and a pair of shiny, black loafers that he’s kept since graduating from Oxford. His shoe size has not changed.

Toward the end of the first half of the concert, which includes music from The Graduate, Pulp Fiction, American Graffiti, Easy Rider, Superfly, Saturday Night Fever, and Help among others, Dudamel conducts “Suicide Scherzo’ from Beethoven’s Symphony No.9 in D minor Op. 125, Scherzo: Molto vivace (once again, if the Reader doesn’t know what this sounds like, Google it while reading this chapter since Malarkey isn’t going to reproduce something as sonically iconic as Beethoven’s 9th, and since Beethoven will make several forays into Malarkey’s novel the Reader should get used to it). Malarkey slowly touches Liliana’s hand and she clasps his. If the Reader needs a better description of this movement, think of it as a CLOSE UP of Malarkey’s right arm, now resting on the arm of the seat they share, and Liliana’s left arm, resting on the arm of the seat they share, as Malarkey’s right hand ever so slowly touches Liliana’s left hand and, as if by instinct, they wrap their fingers around each other as Dudamel concludes Beethoven with a Latin flourish4. This description may not be romantic, but this is the Mad Diary of Malcolm Malarkey and not a Harlequin Romance. If the Reader can’t imagine this conjoining of hands and the interlacing of fingers in the act of holding said hands and, by extension hearts, then, unfortunately, the Reader has no imagination and Malarkey isn’t going to make it easier by expanding on the narrative just to appease you.

At the break, they visit the Concert Hall Café. As they both drink glasses of orange juice, Malarkey rubs his forehead as if he’s trying to think of something.

“You know, it’s true,” Liliana says, sipping her orange juice.

“What is?”

“You do look a bit like an aging Malcolm McDowell.”

“Yeah, I’ve been told that, but I don’t see it. I’m better looking. More hair and taller.”

Liliana raises her eyebrows.

“Really? By how many millimeters.”

“You know, for the life of me I can’t remember where I’ve heard that specific section of Beethoven. I mean I’ve heard the work over and over again, but that part eludes me.”

“Haven’t the slightest,” Liliana smiles, and sips a bit more of her orange juice. By now, the allusion should be obvious to the Reader, but if it isn’t, rent the film Clockwork Orange from Netflix or any other movie rental outfit, buy your own orange juice, and sip.

4 There are significant differences between, say, an Argentine flourish and a Cuban one. Malarkey leaves it to the Reader to decide what kind of Latin flourish s/he imagines Dudamel is flourishing, but if one prefers a Venezuelan flourish then you’re probably right.