Nutritional Deficiency and Gastrointestinal Disease

This chapter will consider a few select nutritional deficiency disorders that are commonly encountered in dermatopathology and have reasonably characteristic microscopic changes. There are definite microscopic resemblances in several of these: necrolytic migratory erythema; acrodermatitis enteropathica/zinc deficiency; and, according to some descriptions, pellagra. Each can show parakeratosis with loss of the granular cell layer and, sometimes, pallor of superficial keratinocytes. This chapter also provides a brief summary of the cutaneous findings in Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis.

Selected Nutritional Deficiency Disorders

Acrodermatitis Enteropathica and Zinc Deficiency

Clinical Features

Acrodermatitis enteropathica is an autosomal recessive disorder presenting in infancy with diarrhea; alopecia; retardation of growth; and an erythematous, scaly, sometimes pustular and bullous eruption. The latter is characteristically acral and periorificial in distribution. Nail dystrophy may be a feature.1,2 Authorities discovered that acrodermatitis enteropathica, a somewhat mysterious disorder in the not-too-distant past, was due to zinc deficiency, resulting in part from abnormalities of gastrointestinal absorption. Onset is often, but not invariably, associated with weaning, because breast milk typically provides adequate quantities of zinc. Investigators have now traced this disease to the SLC39A4 gene, which encodes a zinc transporter protein, Zip4.3 Other causes of zinc deficiency in children or adults include parenteral nutrition without zinc supplementation,4 gastrointestinal surgery, and inflammatory bowel disease.5 In addition to obtaining zinc levels, determination of alkaline phosphatase, a zinc-dependent enzyme, can be of value in selected circumstances where laboratory results are equivocal.

Zinc supplementation is the treatment of choice. It is also important to consider secondary causes of zinc deficiency, such as inflammatory bowel disease.

Microscopic Findings

The key microscopic features are evident in both acrodermatitis enteropathica and acquired zinc deficiency. They include pallor or vacuolization of superficial portions of the epidermis, with diminished or absent granular cell layer and overlying parakeratosis that is often confluent.6,7 Vesicles and bullae result from extensive vacuolization; neutrophils may accumulate in these areas (Fig. 6-1).1,8 The dermis features vasodilatation and perivascular inflammation. With chronicity, varying degrees of epidermal necrosis may be visible, associated with acanthosis (Fig. 6-2).

Differential Diagnosis

The microscopic findings in zinc deficiency are quite similar to those in necrolytic migratory erythema, and differentiation requires correlation with other clinical and laboratory studies. Pustular variants can resemble candidiasis, and in fact Candida infection not infrequently coexists with acrodermatitis enteropathica. Therefore, detection of organisms with periodic acid–Schiff or silver methenamine stains would by itself not exclude the possibility of zinc deficiency. The cutaneous histopathologic findings of biotin deficiency are not well delineated, although there is certainly overlap of the clinical findings, and a patient with both deficiencies has been reported.9 Pellagra can have some microscopic features in common. In fact, some descriptions of pellagra emphasize pallor and vacuolization in keratinocytes in superficial portions of the epidermis. In addition, both pellagra and late-stage zinc deficiency show prominent parakeratosis. However, unlike zinc deficiency, pellagra features prominent dermal edema, it may produce subepidermal bullae, and it often displays basilar hypermelanosis. Late-stage lesions of zinc deficiency show fewer diagnostic changes and can resemble other forms of chronic spongiotic dermatitis.

Necrolytic Migratory Erythema

This syndrome features anemia, weight loss, glossitis, and adult-onset diabetes mellitus. The essential cutaneous feature is a migrating annular erythema with erosions and crusting. This erythema is concentrated in intertriginous areas of the trunk, groin, buttocks, and thighs, and perioral lesions may occur.10,11 Necrolytic migratory erythema is most often associated with a glucagon-secreting islet cell tumor of the pancreas. In a typical case, elevated glucagon levels and reduced plasma amino acids are detected. Other conditions in which glucagons are sometimes elevated, including neuroendocrine hepatic tumors and hepatic cirrhosis, can produce similar cutaneous findings.12,13 Furthermore, changes of necrolytic migratory erythema can accompany jejunal and rectal adenocarcinoma, myelodysplastic syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, pancreatitis, and malabsorption disorders. The occurrence of necrolytic migratory erythema in the absence of a pancreatic tumor is sometimes called the “pseudoglucagonoma syndrome.”14 There appears to be no clear consensus regarding the pathogenesis of necrolytic migratory erythema, but amino acid deficiency due to the catabolic effects of elevated glucagon levels, other nutritional deficiencies (such as zinc and fatty acids), and the effects of certain inflammatory mediators, including arachidonic acid, may all play a role.14,15 Skin lesions resolve with treatment of the underlying tumor and/or correction of nutritional deficiencies.

Microscopic Findings

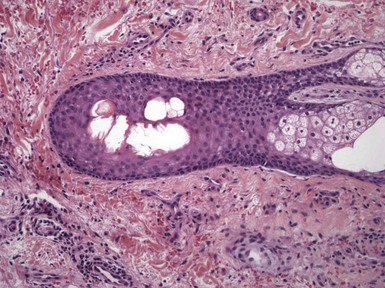

There is often some degree of acanthosis, which may range from mild to marked and psoriasiform. Confluent parakeratosis overlies distinctly vacuolated keratinocytes in the upper portion of the epidermis (Fig. 6-3).16 Necrosis may ensue, with coalescence of vacuoles and neutrophil accumulation, at times producing spongiform pustulation. Subcorneal pustules occasionally form and may be the principal histopathologic finding.17 Within the superficial to mid-dermis, there is a perivascular infiltrate composed mainly of lymphocytes but sometimes including neutrophils.

Figure 6-3 Necrolytic migratory erythema.

Pallor and vacuolization of the surface epidermis are features common to several nutritional deficiency disorders, and they frequently occur in acrodermatitis enteropathica and pellagra as well as necrolytic migratory erythema. Note also the overlying confluent parakeratosis.

Differential Diagnosis

The presence of confluent parakeratosis overlying vacuolated superficial keratinocytes is quite characteristic of necrolytic migratory erythema and should raise suspicions for that diagnosis. However, as mentioned, zinc deficiency (acrodermatitis enteropathica) can have overlapping microscopic features. In general, biopsies showing parakeratosis and pallor or vacuolization of superficial keratinocytes should suggest a nutritional deficiency disorder and prompt investigations in this regard. The clinical presentations of biotin deficiency, pellagra, and childhood acrodermatitis enteropathica are often distinctive, although overlapping features exist.18,19 In addition, adult-onset zinc deficiency can be difficult to distinguish from necrolytic migratory erythema in the absence of laboratory data. Another condition resembling necrolytic migratory erythema but occurring in an acral distribution, particularly on the legs, is termed necrolytic acral erythema. This entity is virtually indistinguishable histopathologically from necrolytic migratory erythema of the glucagonoma syndrome but has a strong association with hepatitis C infection. In this instance, knowledge of the clinical distribution of the lesions is important, and laboratory studies are essential.

Psoriasiform varieties of necrolytic migratory erythema may be difficult to distinguish from true psoriasis. Vacuolization of superficial keratinocytes is not typical of psoriasis in the absence of spongiform pustulation (spongiotic change in superficial portions of the epidermis associated with accumulations of neutrophils), but the latter change can occur in both conditions. Among the other dermatoses characterized by spongiform pustulation, candidiasis would be expected to show organisms at the surface epidermis with periodic acid–Schiff or silver methenamine stains. Unfortunately, coexistence of necrolytic migratory erythema and candidiasis has been reported, so the diagnosis of the former cannot be entirely excluded if organisms are found.20 The occasional case presenting with purely subcorneal pustules would be quite difficult to distinguish from subcorneal pustular dermatosis. However, the variant of immunoglobulin A (IgA) pemphigus manifesting as subcorneal pustules could be recognized through direct immunofluorescence study; in that case, intraepidermal intercellular IgA deposition would be detected.

Pellagra

Classic pellagra develops due to a dietary deficiency of niacin and occurs in patients who eat a diet of “meat (meaning fatback pork), maize, and molasses.” However, the situation is somewhat more complicated, in that individuals deficient in niacin often have additional vitamin deficiencies, which in turn may have deleterious effects on the conversion of tryptophan to niacin. Meanwhile, some otherwise at-risk populations are protected by consumption of other foods rich in niacin or methods of preparation of maize (corn) that successfully release niacin from its bound form.21,22

The conversion of tryptophan to niacin is an important source of the vitamin; therefore, other conditions that alter this pathway can produce a similar clinical picture, resulting in a “secondary” form of pellagra. Examples are the autosomal recessive disorder Hartnup disease, in which absorption of tryptophan is impaired,23 or carcinoid, in which the tumor diverts tryptophan to the production of serotonin.24 In addition, certain drugs can interfere with niacin biosynthesis and promote the signs and symptoms of pellagra, including antituberculous drugs (isoniazid, pyrazinamide) and 5-fluorouracil.25,26

Clinical features of pellagra include depression, weakness, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. The chief cutaneous finding is photosensitivity, producing erythema and, eventually thickening, scaling, and hyperpigmentation involving the skin of the face, neck, extensor forearms and dorsa of the hands. Lesions on the neck and chest produce the characteristic Casal necklace. Scale and follicular plugging involving the nose, sometimes termed dyssebacia, produces a roughened appearance.

Treatment includes dietary management and niacin supplementation, in addition to correction of other associated nutritional deficiencies. Management of any underlying disorders, such as alcoholism or potential secondary causes of pellagra, may also be important.

Microscopic Findings

The microscopic descriptions of pellagra vary somewhat, depending on the source. Several authors emphasize early dermal edema and chronic perivascular inflammation. Hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and basilar hypermelanosis are apparent, particularly in older lesions. Bullae may arise either subepidermally, related to the marked dermal edema, or intraepidermally. Researchers have described pallor and vacuolization of upper layers of the epidermis, probably the source of intraepidermal blistering. In addition, they have observed sebaceous gland prominence and follicular plugging, especially in biopsies of the nose or central face.18,27,28

Differential Diagnosis

When lesions display pallor or vacuolization of the surface epidermis, they can closely resemble zinc deficiency and necrolytic migratory erythema.29 In fact, these deficiency disorders have often been grouped together, at least conceptually. It must also be kept in mind that some individuals with pellagra may have multiple nutritional deficiencies, and the possibility that vacuolization is actually due to deficiencies in zinc, biotin, or other amino acids should be kept in mind. It has even been proposed that the manifestations of acrodermatitis enteropathica and pellagra stem from a common deficiency of picolinic acid, which like nicotinic acid derives from tryptophan.19 However, subepidermal bullae and basilar hypermelanosis in this setting are certainly suggestive of pellagra. Follicular plugging can also be seen in vitamin C deficiency (see later discussion), but the formation of “corkscrew hairs” is a feature of the latter disorder.

Vitamin C Deficiency (Scurvy)

Ascorbic acid deficiency is encountered in alcoholic patients and individuals on restricted diets, with reduced intake of fruits and vegetables. It is an important factor in normal collagen biosynthesis and thereby contributes to the integrity of small vessels. Humans and some other species are incapable of synthesizing the vitamin and therefore are dependent on external sources. Mucocutaneous manifestations are common and include petechiae, perifollicular hemorrhages, ecchymoses, bleeding gums, and “woody edema” of the lower extremities. Hyperkeratosis of hair follicles is associated with coiling of hair shafts, the so-called “corkscrew hairs.”30

Cutaneous Manifestations of Selected Gastrointestinal Diseases

Clinical Features

Crohn disease, including granulomatous colitis, can be associated with perianal abscesses, sinuses, fistulae, episcleritis and uveitis, aphthous stomatitis, periorificial ulcers with formation of “cobblestoned papules,” erythema nodosum, and pyoderma gangrenosum.33 Granulomas in perianal skin tags can provide an important clue to the diagnosis of Crohn disease.34 Examples of polyarteritis nodosa in Crohn disease have also been described,35 and the author has seen at least one example of this association. Cutaneous involvement in areas widely separated from the gastrointestinal tract is commonly termed metastatic Crohn disease. These lesions can consist of erythematous nodules or ulcers and can involve the face, trunk (especially flexural areas), and extremities.36,37

Microscopic Findings

Many of these lesions have nonspecific histopathologic findings, although the clinical setting (e.g., perianal abscesses and fistulae) can be quite suggestive of Crohn disease. The most characteristic feature is granulomatous inflammation, which may be seen in the perianal, perioral, and cutaneous “metastatic” lesions. The typical finding is a noncaseating granuloma, associated with a few scattered lymphocytes or small macrophages (Fig. 6-5).38 Lesions clinically resembling erythema nodosum can either show classic findings of erythema nodosum or granulomatous elements, including granulomatous vasculitis.

Differential Diagnosis

The noncaseating granulomas of Crohn disease closely resemble those of sarcoidosis. This distinction can be particularly difficult in examples of metastatic Crohn disease when lesions are sampled at sites other than the perianal or perioral regions. For correct classification, additional clinical information may be necessary.

Ulcerative Colitis

Cutaneous findings develop in ulcerative colitis in up to 34% of reported cases. A number of these develop in both Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis, including aphthous stomatitis, erythema nodosum, and pyoderma gangrenosum. Erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, and acute toxic arthritis are associated with active bowel disease and most often respond to surgical resection of the involved bowel. Pustular disease is particularly prone to occur in ulcerative colitis; its manifestations include discrete, small pustular lesions; pustules that evolve into pyoderma gangrenosum39; and pyoderma vegetans of Hallopeau, which consists of vegetative plaques with elevated borders. Some authorities consider this to be the same disorder as blastomycosis-like pyoderma, and at one time it was erroneously classified with pemphigus vegetans. Similar vegetative lesions of the oral cavity are called pyostomatitis vegetans.40,41

Microscopic Findings

Lesions of pyoderma vegetans show pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and intraepidermal abscesses, usually composed of neutrophils but sometimes including eosinophils (Fig. 6-6).42 There is a rather heavy, mixed dermal inflammatory infiltrate. Bacterial cultures may demonstrate Staphylococcus aureus, but this may in fact be a secondary invader rather than the etiologic agent for this disorder.

Differential Diagnosis

As previously mentioned, the changes of pyoderma vegetans were at one time linked to pemphigus vegetans, which is also characterized by irregular acanthosis and intraepidermal abscesses. However, in pemphigus vegetans, the intraepidermal abscesses are usually composed of eosinophils, foci of acantholysis can sometimes be found, and direct immunofluorescence shows intercellular epidermal fluorescence with antibodies to IgG. Acantholysis is not a feature of pyoderma vegetans, and direct immunofluorescence studies are negative. Microscopically, the epidermal changes of pyoderma vegetans may reach pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia proportions. Together with intraepidermal neutrophilic abscesses, these findings may also resemble “deep” fungal infections (i.e., North American blastomycosis, South American blastomycosis, some examples of cryptococcosis and coccidioidomycosis) as well as in some atypical mycobacterial infections and protothecosis. Therefore, special stains for these organisms and/or culture studies may be necessary.

References

1. Jensen, SL, McCuaig, C, Zembowicz, A, et al. Bullous lesions in acrodermatitis enteropathica delaying diagnosis of zinc deficiency: a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(suppl 1):1–13.

2. Perafan-Riveros, C, Franca, LF, Alves, AC, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:426–431.

3. Maverakis, E, Fung, MA, Lynch, PJ, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:116–124.

4. Ferrandiz, C, Henkes, J, Peyri, J, et al. Acquired zinc deficiency syndrome during total parenteral alimentation. Clinical and histopathological findings. Dermatologica. 1981;163:255–266.

5. Krasovec, M, Frenk, E. Acrodermatitis enteropathica secondary to Crohn’s disease. Dermatology. 1996;193:361–363.

6. Niemi, KM, Anttila, PH, Kanerva, L, et al. Histopathological study of transient acrodermatitis enteropathica due to decreased zinc in breast milk. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:382–387.

7. Gonzalez, JR, Botet, MV, Sanchez, JL. The histopathology of acrodermatitis enteropathica. Am J Dermatopathol. 1982;4:303–311.

8. Borroni, G, Brazzelli, V, Vignati, G, et al. Bullous lesions in acrodermatitis enteropathica. Histopathologic findings regarding two patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:304–309.

9. Lagier, P, Bimar, P, Seriat-Gautier, S, et al. [Zinc and biotin deficiency during prolonged parenteral nutrition in the infant]. Presse Med. 1987;16:1795–1797. [[in French]].

10. Leichter, SB. Clinical and metabolic aspects of glucagonoma. Medicine (Baltimore). 1980;59:100–113.

11. Vandersteen, PR, Scheithauer, BW. Glucagonoma syndrome. A clinicopathologic, immunocytochemical, and ultrastructural study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:1032–1039.

12. Technau, K, Renkl, A, Norgauer, J, et al. Necrolytic migratory erythema with myelodysplastic syndrome without glucagonoma. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:110–112.

13. Marko, PB, Miljkovic, J, Zemljic, TG. Necrolytic migratory erythema associated with hyperglucagonemia and neuroendocrine hepatic tumors. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat. 2005;14:161–164. [166].

14. Tierney, EP, Badger, J. Etiology and pathogenesis of necrolytic migratory erythema: review of the literature. MedGenMed. 2004;6:4.

15. Peterson, LL, Shaw, JC, Acott, KM, et al. Glucagonoma syndrome: in vitro evidence that glucagon increases epidermal arachidonic acid. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11:468–473.

16. Franchimont, C, Pierard, GE, Luyckx, AS, et al. Angioplastic necrolytic migratory erythema. Unique association of necrolytic migratory erythema, extensive angioplasia, and high molecular weight glucagon-like polypeptide. Am J Dermatopathol. 1982;4:485–495.

17. Kheir, SM, Omura, EF, Grizzle, WE, et al. Histologic variation in the skin lesions of the glucagonoma syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol. 1986;10:445–453.

18. Hendricks, WM. Pellagra and pellagralike dermatoses: etiology, differential diagnosis, dermatopathology, and treatment. Semin Dermatol. 1991;10:282–292.

19. Krieger, IE. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and the relation to pellagra. Med Hypotheses. 1981;7:539–547.

20. Katz, R, Fischmann, AB, Galotto, J, et al. Necrolytic migratory erythema, presenting as candidiasis, due to a pancreatic glucagonoma. Cancer. 1979;44:558–563.

21. Karthikeyan, K, Thappa, DM. Pellagra and skin. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:476–481.

22. Jagielska, G, Tomaszewicz-Libudzic, EC, Brzozowska, A. Pellagra: a rare complication of anorexia nervosa. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;16:417–420.

23. Seyhan, ME, Selimoglu, MA, Ertekin, V, et al. Acrodermatitis enteropathica-like eruptions in a child with Hartnup disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:262–265.

24. Castiello, RJ, Lynch, PJ. Pellagra and the carcinoid syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1972;105:574–577.

25. Darvay, A, Basarab, T, McGregor, JM, et al. Isoniazid induced pellagra despite pyridoxine supplementation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1999;24:167–169.

26. Stevens, HP, Ostlere, LS, Begent, RH, et al. Pellagra secondary to 5-fluorouracil. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:578–580.

27. Findlay, GH, Rein, L, Mitchell, D. Reactions to light on the normal and pellagrous Bantu skin. Br J Dermatol. 1969;81:345–351.

28. Moore, RA, Spies, TD, Cooper, ZK. Histopathology of the skin in pellagra. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1942;46:106–111.

29. van Beek, AP, de Haas, ER, van Vloten, WA, et al. The glucagonoma syndrome and necrolytic migratory erythema: a clinical review. Eur J Endocrinol. 2004;151:531–537.

30. Hirschmann, JV, Raugi, GJ. Adult scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:895–906. [quiz 907-910].

31. Walker, A. Chronic scurvy. Br J Dermatol. 1968;80:625–630.

32. Ellis, CN, Vanderveen, EE, Rasmussen, JE. Scurvy. A case caused by peculiar dietary habits. Arch Dermatol. 1984;120:1212–1214.

33. Schoetz, DJ, Jr., Coller, JA, Veidenheimer, MC. Pyoderma gangrenosum and Crohn’s disease. Eight cases and a review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 1983;26:155–158.

34. Taylor, BA, Williams, GT, Hughes, LE, et al. The histology of anal skin tags in Crohn’s disease: an aid to confirmation of the diagnosis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1989;4:197–199.

35. Kahn, EI, Daum, F, Aiges, HW, et al. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa associated with Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1980;23:258–262.

36. Lebwohl, M, Fleischmajer, R, Janowitz, H, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:33–38.

37. Goh, M, Tekchandani, AH, Wojno, KJ, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease involving penile skin. J Urol. 1998;159:506–507.

38. Witkowski, JA, Parish, LC, Lewis, JE. Crohn’s disease—non-caseating granulomas on the legs. Acta Derm Venereol. 1977;57:181–183.

39. Salmon, P, Rademaker, M, Edwards, L. A continuum of neutrophilic disease occurring in a patient with ulcerative colitis. Australas J Dermatol. 1998;39:116–118.

40. Markiewicz, M, Suresh, L, Margarone, J, III., et al. Pyostomatitis vegetans: a clinical marker of silent ulcerative colitis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:346–348.

41. Kitayama, A, Misago, N, Okawa, T, et al. Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans after subtotal colectomy for ulcerative colitis. J Dermatol. 2010;37:714–717.

42. Bianchi, L, Carrozzo, AM, Orlandi, A, et al. Pyoderma vegetans and ulcerative colitis. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1224–1227.