Drugs and Physical Agents

Considering the notable proliferation of new therapeutic agents during recent years, it is not surprising that numerous adverse reactions have been reported. Many of these effects involve the skin. These reactions, of course, add to the growing list of cutaneous reactions to well-established therapeutic agents. Some of these reactions, such as urticaria and pruritus, are common to many if not most drugs but are clinically and histopathologically nonspecific. Others, such as leukocytoclastic vasculitis or lesions resulting from thrombosis, may be a reflection of profound systemic abnormalities but again tend to lack histopathologic specificity. Some drug reactions are primarily considered in other chapters because they are best defined by the histopathologic features they have in common with other, non–drug-related conditions. Examples include erythema multiforme and toxic epidermal necrolysis, lichenoid drug eruption, penicillamine-induced elastosis perforans serpiginosa, pemphigus induced by drugs (penicillamine, captopril), and pseudoporphyria due to drugs (furosemide, oxaprozin). Drug reactions that are relatively unique will be considered in this chapter. These include fixed drug eruptions, reactions to antineoplastic agents or recombinant cytokines, phototoxic and photoallergic eruptions, drug-induced pigment alterations (due to minocycline, amiodarone, and clofazimine), halogen eruptions, reactions to metals, and drug-induced pseudolymphoma.

Ultraviolet exposure is not only a factor in phototoxic and photoallergic reactions, chronic solar damage, and certain skin cancers, but it also plays a role in a number of unique photodermatoses, including polymorphic light eruption, actinic prurigo, hydroa vacciniforme, chronic actinic dermatitis and actinic reticuloid, and solar urticaria. Other physical agents responsible for unique skin lesions include thermal injury (burns, erythema ab igne), x-rays (radiation dermatitis), and blunt trauma (calcaneal petechiae).

Exanthems Caused by Drugs

Clinical Features

Many drugs are known to produce more or less generalized eruptions that can be categorized as drug-induced exanthems. These eruptions are often described as maculopapular or morbilliform. They frequently occur approximately 9 days (1–3 weeks) following administration of the agent; that figure can vary depending on whether there has been previous exposure (i.e., sensitization) to the drug or a chemically related compound. These eruptions can occur in response to ampicillin or a few other medications in patients who also have mononucleosis or cytomegalovirus infection. In fact, patients with lymphotrophic viral infections are considered to be at increased risk for drug eruptions, and there is also a link between maculopapular drug eruptions and respiratory or urinary tract infections.1 The diagnosis of drug eruption can be straightforward in the absence of complicating factors but can be quite challenging in patients who are on multiple medications, are at risk for viral infections, or might have an autoeczematization (id) reaction to foci of inflammation or infection of various types; this is frequently an issue in consultations on hospitalized patients. Drug eruptions of this type are considered type IV (delayed hypersensitivity) reactions and are largely mediated by T cells.2

Microscopic Findings

It is difficult to find literature describing a typical histopathologic image for maculopapular or morbilliform drug eruptions. This is likely due, in part, to the difficulty in confirming with certainty that a particular eruption is in fact due to a drug and not to some other factor or combination of factors. Fellner and colleagues described both mild, focal spongiosis and vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer in examples of penicillin-induced morbilliform eruptions,3 and this agrees with the author’s experience with lesions strongly suspected to be due to drugs. Ackerman emphasized interface changes in morbilliform drug eruptions: vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer; a sparse lymphohistiocytic infiltrate along the dermal-epidermal interface; and, sometimes, extravasated erythrocytes in the papillary dermis.4 Kitamura and associates also noted interface changes and satellite cell necrosis of epidermal keratinocytes in patients with eruptions due to drugs containing sulfhydryl groups (e.g., D-penicillamine, captopril).5 On the other hand, Terui and Tagami noted eczematous changes in drug eruptions from carbamazepine, reproduced with patch and photopatch testing.6 Langerhans cells increase in number and prominence of their dendrites in drug eruptions, consistent with the concept that these are type IV delayed hypersensitivity reactions.2 Much diagnostic weight is placed on the presence of eosinophils in drug eruptions, because they are a frequent accompaniment of “hypersensitivity” reactions. They are indeed often present, probably as a result of elevated levels of interleukin-5,7 and the author routinely searches for them. However, they are not always numerous, and their absence does not exclude a diagnosis of drug eruption (Fig. 12-1).

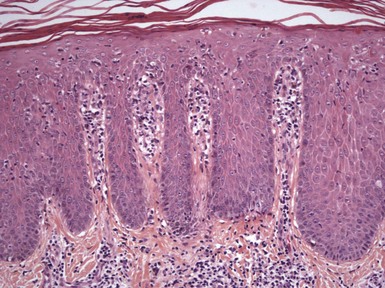

Figure 12-1 Drug-induced exanthem.

Findings in this example include parakeratosis; mild spongiosis; and a mild perivascular and interstitial, superficial dermal infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes and a few eosinophils. This lesion does not show a great deal of interface change, but slight focal vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer can be appreciated.

Differential Diagnosis

The histopathologic differential diagnosis of drug-induced exanthems is rather broad and includes urticarial tissue reactions unrelated to drug, viral exanthems, and id reactions. All of these show mild perivascular inflammatory infiltrates, and viral exanthems and id reactions can show mild interface or spongiotic changes. Low-grade contact dermatitis or hypersensitivity reactions to arthropods or airborne allergens also show overlapping features. In such cases, clinical data and information about current or past medications can be crucial, although, unfortunately, feedback in these cases is often difficult to obtain. In most drug exanthems, spongiotic or interface changes are mild, but marked spongiosis may be confused with other forms of eczematous dermatitis, whereas extensive vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer can have resemblances to lichen planus and other lichenoid dermatoses. Eruptions consisting of distinctly lichenoid papules containing eosinophils or plasma cells may actually represent lichenoid drug eruptions (see Chapter 3). Several authors have noted a close microscopic resemblance between drug eruptions and graft-versus-host disease, particularly in the case of sulfhydryl-containing compounds5; both can show vacuolar alteration of the epidermal basilar layer, keratinocyte necrosis (apoptosis) with satellite cell necrosis, and eosinophils in the dermal infiltrate.5,8 Therefore clinical data, including a list of medications and the timing of the eruption related to transplantation or first administration of a drug, are crucial when evaluating biopsies of patients at risk for both conditions.

Interface Dermatitis

Clinical Features

Fixed drug eruption consists of isolated, erythematous patches or bullae, sometimes with a targetoid appearance, that recur in the same site with exposure to the same medication.9 The lesions are often well demarcated, and as they resolve, they leave postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Some of the agents known to cause fixed drug eruption are sulfonamides, paracetamol, naproxen, barbiturates, and tetracycline. A nonpigmented variant also occurs, elicited by pseudoephedrine (including a form contained in Chinese herbal medicine)10,11 and eprazinone.12 A refractory period of varying duration can be observed in involved sites.13 Typically, only one or a few lesions are present. Favored sites include the oral and genital regions. Resident intraepidermal CD8+ T cells apparently play a role in the development of these lesions.14

Microscopic Findings

The characteristic findings of fixed drug eruption are those of interface (lichenoid) dermatitis. The features include vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer, frequently extensive; formation of apoptotic keratinocytes, seen at all levels of the epidermis; and a superficial and deep dermal infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and neutrophils (Fig. 12-2). The resulting pigmentary incontinence is often pronounced, although as previously noted, a nonpigmented fixed drug eruption also occurs. Spongiosis is a feature in some cases. The author first encountered the description of intraepidermal vesiculation in acute fixed drug eruption in Ackerman’s textbook of inflammatory skin diseases.15 Occurring in acute fixed drug eruption, this change is due to intracellular edema; however, vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer and apoptotic (necrotic) keratinocytes are also apparent. Several authors have reported a “neutrophilic” form of the disorder, in which early lesions show spongiosis, neutrophil exocytosis, and neutrophilic intraepidermal abscesses in addition to perivascular dermal neutrophilic and eosinophilic infiltrates16,17 (Fig. 12-3). There is some debate about whether these changes represent a variant form of fixed drug eruption or a stage in the evolution of some lesions. However, it is clear that neutrophils are an important component of fixed drug eruption and may be of some diagnostic importance.

Differential Diagnosis

The chief consideration in the microscopic differential diagnosis is erythema multiforme, a condition that shares the features of vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer; apoptotic keratinocytes, often at all levels of the epidermis; and a perivascular dermal infiltrate. Clinically, the history of an isolated lesion recurring at the same site certainly favors fixed drug eruption, but multiple lesions can occur, and a widespread variant of bullous fixed drug eruption has also been reported.18 In contrast to erythema multiforme, which tends to show a relatively mild superficial dermal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, fixed drug eruption tends to show a superficial and deep dermal infiltrate that contains neutrophils as well as lymphocytes. When present, intraepidermal vesiculation also favors fixed drug eruption, because bullae in erythema multiforme are subepidermal. Some examples of pityriasis lichenoides acuta can closely resemble erythema multiforme and, by extension, can also mimic fixed drug eruption. However, the wedge-shaped dermal infiltrate in pityriasis lichenoides is composed mainly of lymphocytes, and vascular changes can qualify as lymphocytic vasculitis. Neutrophils, if present, are generally confined to the surface of necrotic lesions. Early lesions of fixed drug eruption that show intraepidermal vesiculation on the basis of intracellular edema can bear a resemblance to herpes simplex or varicella zoster infection of the skin, but the formation of multinucleated giant cells, characteristic nuclear changes, and intranuclear inclusions of the latter disorders are not observed,15 and immunohistochemical stains for herpesviruses are negative. Isolated examples of “neutrophilic” fixed drug eruption could resemble other intraepidermal pustular conditions, including acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis and herpetiform or IgA pemphigus. In addition to the characteristic clinical presentation, fixed drug eruption would also be expected to show significant interface changes, and direct immunofluorescence studies would fail to show intercellular IgG, IgA, or C3 deposition as would be characteristic of forms of pemphigus.

Reactions to Antineoplastic Agents

A wide variety of reactions to antineoplastic (chemotherapeutic) agents have been reported, although the best known and probably most common type of eruption is interface (lichenoid) dermatitis. A study of the histopathology of cutaneous chemotherapy reactions generally involves researching the literature concerning individual therapeutic agents or classes of compounds, but fortunately several very useful publications have summarized the microscopic findings for the various agents in this category.19,20 A number of important but nonetheless histopathologically nonspecific cutaneous reactions have been reported, including urticaria, contact urticaria, and angioedema (chlorambucil, nitrogen mustard, and bleomycin, respectively)19; dermal inflammatory infiltrates accompanying maculopapular eruptions or erythroderma (bromodeoxyuridine, bortezomib)19,21; small vessel necrotizing and urticarial vasculitis or microthrombi (bortezomib, pemetrexed, and doxorubicin, respectively)19,20,22; spongiotic dermatitis, sometimes as a manifestation of allergic contact or photodermatitis (dacarbazine, mechlorethamine, 5-fluorouracil, methotrexate)23–26; and pigmentation due to basilar hypermelanosis and/or pigmentary incontinence (carmustine, busulfan, 5-fluorouracil, and bleomycin, the latter responsible for the characteristic flagellate hyperpigmentation).19,27–29 Like other types of medications, some chemotherapeutic agents produce characteristic eruptions that are discussed elsewhere, such as erythema multiforme (imatinib), toxic epidermal necrolysis (cytarabine, methotrexate, mithramycin), and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (imatinib).19,20 Reactions to some of the newer chemotherapeutic agents are listed in Table 12-1.

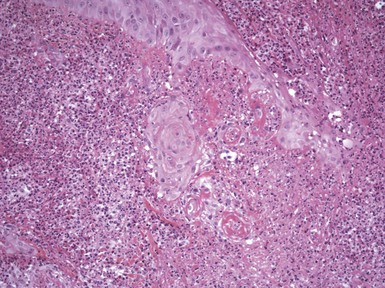

Table 12-1

Unusual Reactions to Newer Chemotherapeutic Agents

However, the most common type of chemotherapy reaction, encountered across a number of classes of agents, is lichenoid dermatitis, which includes several manifestations of dyskeratosis or so-called “maturation arrest” (as previously noted, erythema multiforme and toxic epidermal necrolysis, conditions also generally grouped with the interface dermatoses, are discussed elsewhere). The clinical presentations of these eruptions can vary widely and include a lichen planus–like eruption (FT-207—a modified form of 5-fluorouracil, hydroxyurea, imatinib), maculopapular eruptions (busulfan, cytarabine, bleomycin), a “scaly follicular eruption” (liposomal doxorubicin), and a localized dermatitis (dacarbazine).19,20 Acral erythema, or hand-foot syndrome, is a distinctive condition particularly associated with docetaxel but also with cyclophosphamide; cytarabine; 5-fluorouracil and its prodrug, tegafur; and doxorubicin. Discrete, erythematous to violaceous patches or plaques involve palms and soles, dorsa of the hands and feet, and occasionally other locations. Various forms of dysesthesia may also be present.20,35 Another form of acral erythema is associated with the multikinase inhibitors sorafenib and sunitinib. This is apparently clinically distinctive from other varieties of acral erythema in that plaques are more discrete and hyperkeratotic,34 although there appears to be at least some histopathologic overlap. A lesion known as fixed erythrodysesthesia plaque that has resemblances to acral erythema arises proximally to the site of intravenous infusion of docetaxel; it slowly resolves, leaving residual hyperpigmentation and desquamative changes.39 The subgroup of lesions with histopathologic changes of dysmaturation presents with widely variable clinical appearances, including maculopapular (busulfan, etoposide) and intertrigo-like (liposomal doxorubicin) eruptions as well as acral erythema.40,41

Microscopic Findings

Some examples of chemotherapy-induced lichenoid eruptions closely resemble lichen planus (e.g., FT-207) (Fig. 12-4). There may also be a combination of interface dermatitis with interstitial dermal inflammation, as described in reactions to the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib,21 or mixed spongiotic and interface changes, as described in some examples of acral erythema and erythrodysesthesia plaque.35 Lesions with dysmaturation often show vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer and disorganized keratinocytes with large amounts of cytoplasm, enlarged or otherwise atypical nuclei, necrotic or apoptotic cells, and a lack of orderly maturation with ascent to more superficial portions of the epidermis. Large areas of the epidermis may be involved (Fig. 12-5), or the changes may consist of scattered keratinocytes with large vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli—“busulfan cells”42 or “starburst” mitoses as seen with etoposide therapy.43 Squamous syringometaplasia may accompany or be the predominating feature of some chemotherapy reactions; implicated agents include cytarabine,44 bleomycin,45 imatinib,46 liposomal doxorubicin,47 and vincristine48 (Fig. 12-6). A close relationship between squamous syringometaplasia and neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis has been postulated (see “Neutrophilic Eccrine Hidradenitis”); several agents produce both reactions (e.g., cytarabine, bleomycin).44

Figure 12-4 Chemotherapy reaction, lichenoid type.

This lichenoid tissue reaction pattern is due to etoposide.

Differential Diagnosis

Lesions with distinctly lichenoid features need to be distinguished from true lichen planus; lichenoid drug eruption due to nonantineoplastic agents; or in the case of solitary lesions, lichenoid keratosis. When presenting with a mixture of lichenoid and spongiotic changes, certain viral exanthems, such as the one that accompanies Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, are included in the differential diagnosis. Epidermal dysmaturation occupying a broad front of epidermis could be confused with actinic keratosis, but often the latter shows some stretches with atypia confined to basilar epidermis—a change not expected in chemotherapy reactions. In addition, the extreme cellular and nuclear pleomorphism of Bowen disease is not observed, and the acantholysis of Grover disease, Darier disease, or other forms of focal acantholytic dyskeratosis is not apparent. Squamous syringometaplasia has been described in a number of clinical situations unrelated to chemotherapy or malignancy49; examples include burns,50 phytophotodermatitis,51 and administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents.52 Chemotherapy reactions of the dysmaturation type should also be distinguished from graft-versus-host disease. Both can feature lichenoid dermatitis, including vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer and formation of apoptotic keratinocytes. However, cytologic atypia and loss of orderly keratinocyte maturation are not usual microscopic criteria for graft-versus-host disease. One case the author reported of nonulcerated epidermal dysmaturation due to pegylated liposomal doxorubicin showed numerous neutrophils in the dermal infiltrate; this is not generally reported as a finding in graft-versus-host disease, but further study is needed to determine if this might be a valid differentiating feature. However, keratinocyte dysmaturation can sometimes be seen in patients with graft-versus-host disease who have not received cytoreductive therapy.53 Furthermore, because chemotherapy effects on the epidermis may be sporadic and not associated with significant clinical disease, they can be found coincidentally in biopsies done for other reasons, including the evaluation for possible graft-versus-host disease. For this reason, Horn has recommended avoiding areas of chemotherapy effects when microscopically searching for changes of graft-versus-host disease.54

Neutrophilic Eccrine Hidradenitis

Clinical Features

Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis presents as papules or plaques involving acral sites as well as the face and trunk. This reaction is most closely associated with induction chemotherapy for malignancy, especially leukemias and lymphomas. However, it has also been seen in association with solid tumors.55 Although the most frequently implicated drug is cytarabine, the lesions have been reported with other agents, including bleomycin,56 docetaxel,40 and certain antibiotics. The reaction has also been identified in patients with malignancies who have not been treated; in at least one example, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis heralded the onset of acute myelogenous leukemia.57 The same changes can occur in patients without underlying malignancy58; examples have been found in HIV-infected patients,59 in an individual subjected to trauma and exposure to aluminum dust,60 and in an otherwise healthy woman.61 Older literature referred to the occurrence of “sweat gland abscesses” in children, consisting of papules and nodules on the extremities. In more recent years, there have been additional reports of neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis associated with infection.62 Another condition, known as painful plantar erythema or idiopathic plantar hidradenitis, consists of painful erythematous nodules occurring on the plantar surfaces of the feet but also occasionally on the palms. These lesions are prone to occur in otherwise healthy children. Recurrences are common, but the disorder is self-limited and tends to respond to conservative therapies. Some of these cases represent neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, but others demonstrate a mixed septal-lobular panniculitis with vasculitis and do not target the eccrine sweat apparatus.63

Microscopic Findings

There is vacuolar alteration or necrosis of sweat glands, associated with a neutrophilic infiltrate that appears to specifically target these structures (Fig. 12-7). Initial descriptions emphasized involvement of the eccrine secretory coil,64 although the ducts are also involved.65 The lesions of idiopathic plantar hidradenitis are said to specifically involve portions of the eccrine sweat duct, with relative sparing of the secretory apparatus.66 Squamous syringometaplasia can be associated with neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, and responsible chemotherapeutic agents such as cytarabine can produce either type of reaction, suggesting these may be ends of a spectrum of sweat gland involvement.44 In contrast to chemotherapy-associated neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, syringosquamous metaplasia is not a feature of idiopathic plantar hidradenitis.66 Adjacent connective tissue changes can include edema, mucin deposition, and hemorrhage.55

Differential Diagnosis

Neutrophilic infiltration of sweat glands, in the absence of other significant dermal abnormalities (e.g., the widespread dermal neutrophilic infiltrates that can be seen as part of an infectious process), is relatively specific for neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis and therefore is highly diagnostic. The probability of chemotherapy effect is high, especially when a degree of squamous syringometaplasia is also identified, but as noted previously, other clinical possibilities (e.g., HIV infection, idiopathic plantar hidradenitis) must be borne in mind.

Selected Reactions to Recombinant Cytokines

A variety of reactions have been reported to recombinant cytokines. Few of these are specific, and most could occur from other therapeutic agents or as idiopathic processes. Selected reactions to epidermal growth receptor inhibitors and multikinase inhibitors have already been discussed. Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) are used (1) to enhance recovery from neutropenia following cancer chemotherapy and (2) to promote an increase in hematopoietic stem cells in the blood of donors in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Both stimulate stem cell production of granulocytes and, in the case of GM-CSF, also the production of monocytes, which mature to form macrophages in a variety of tissues, including skin. Side effects of therapy include development of a variety of neutrophil-rich disorders, including Sweet syndrome, bullous pyoderma gangrenosum, and folliculitis.67,68 These agents can produce a widespread maculopapular eruption, which on biopsy shows spongiosis; exocytosis; scattered apoptotic keratinocytes; and a superficial, perivascular dermal infiltrate containing lymphocytes, eosinophils, and neutrophils.69,70 A characteristic feature of these eruptions consists of large, atypical macrophages, some showing elastophagocytosis or occasional mitotic activity68–70 (Fig. 12-8).

Figure 12-8 Cutaneous reaction to granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor.

Scattered apoptotic keratinocytes can be seen, and there is a dermal infiltrate consisting of perivascular and interstitial lymphocytes and macrophages. In this example, basal cell vacuolization predominates over spongiosis.

Phototoxic and Photoallergic Drug Reactions

Clinical Features

A number of drugs are capable of producing cutaneous reactions when patients are exposed to ultraviolet light, especially ultraviolet A (UVA) irradiation. Most examples are believed to be due to a direct toxic effect of the drug with ultraviolet exposure, termed phototoxicity. Presumably, oxygen free radicals, singlet oxygen, and other products generated in the process are responsible for the tissue damage, although photoproducts of a particular drug may also be responsible.71,72 The clinical effects resemble an exaggerated sunburn, with sparing of intertriginous locations and sites covered by protective clothing or otherwise shielded from ultraviolet exposure. Presumably, any individual can develop a phototoxic reaction to medication, given sufficient exposure to the drug and to ultraviolet radiation. Well-known phototoxic drugs include furosemide, tetracyclines, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. In photoallergy, the changes are due to a type IV, delayed hypersensitivity response. Reactions can occur to topically applied agents (photocontact dermatitis) or to systemically administered agents; the latter may be more difficult to prove but can be investigated through photopatch testing.73 Clinical features are generally those of spongiotic (eczematous) dermatitis, although there may be considerable overlap with phototoxic reactions. Extension of the dermatitis to photoprotected areas can occur. Only those individuals who have been sensitized to a particular agent develop this type of reaction, and presumably small quantities of the drug may be sufficient to elicit the eruption in the context of ultraviolet exposure. Drugs producing photoallergic reactions when administered systemically include griseofulvin, sulfonamides, and (again) nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents.

Microscopic Findings

Phototoxic reactions show vacuolated to necrotic (apoptotic) keratinocytes within the epidermis: the so-called “sunburn cells,”74 together with varying degrees of dermal edema and a dermal infiltrate (either superficial or superficial and deep) composed mainly of lymphocytes but sometimes including neutrophils and a few eosinophils (Fig. 12-9). Spongiosis can also be observed in some examples of phototoxic dermatitis. In photoallergic dermatitis, the image is that of a spongiotic dermatitis, with a perivascular infiltrate composed largely of lymphocytes, and lymphocyte exocytosis75 (Fig. 12-10). A recent study of experimental photoallergy in mice, using afloqualone, showed massive infiltration of eosinophils as well as lymphocytes at the challenged site; the authors postulate a role for sensitized T helper 2 (Th2) cells and locally produced chemokines in eliciting this eosinophilic drug photoallergy.76

Differential Diagnosis

Although the histopathologic distinction between phototoxic and photoallergic drug eruptions sounds straightforward, in actual practice it is much more difficult because the features can significantly overlap. This is more likely to be the case when lesions have been present for more than a few days, at which point the changes may be virtually indistinguishable. Furthermore, it may be impossible to distinguish phototoxic dermatitis from simple sunburn, or photoallergic dermatitis from non–photo-induced allergic contact dermatitis or other forms of eczematous dermatitis. Clinical suspicion of a photosensitive dermatitis is a key, but most often it is necessary to point out that the microscopic findings are compatible with, but not absolutely diagnostic of, drug-induced photodermatitis. Careful physical examination, a review of the patient’s medications, and correlation of the outbreak of the eruption with episodes of ultraviolet exposure are necessary to ensure the proper diagnosis, and photopatch testing may be important if photoallergy is considered a strong possibility. Clinical follow-up is also important; otherwise, the pathologist has little opportunity to learn from the case or to potentially apply the lessons learned to future cases.

Pigmentary Changes Caused by Drugs

Clinical Features

Several medications can produce pigment alterations that are of clinical significance. A few of these drugs are sufficiently distinctive from a histopathologic standpoint that they warrant discussion here—minocycline, amiodarone, and clofazimine.

Minocycline first became available for clinical use in 1967. Black discoloration of the thyroid follicles of animals receiving minocycline was reported in the same year.77 Since that time, at least three types of minocycline-induced cutaneous pigmentation have been described: type I, a blue-black pigmentation developing in areas of inflammation and scar78; type II, a blue-gray pigmentation forming over otherwise normal skin of the arms, legs, or face79; and type III, a diffuse pigmentation that is most often described as “muddy brown” in nature.80 Pigmentation of the nails and nail beds occurs,81,82 and pigment changes can also develop from minocycline-induced fixed drug eruption.83 Localized pigmentation at a site of tissue injury does not appear to be directly related to the duration of treatment, and this has been reported to occur as rapidly as 1 to 3 months following the onset of minocycline therapy.81 The evidence suggests that the diffuse type of pigmentation is more dependent on total dose and duration of therapy. Patients have been on minocycline for about 3 years, with total doses ranging from 130 to 144 g.84 The evidence to date suggests that most examples of minocycline pigmentation are due to cutaneous deposits of the drug or a metabolite, chelated with iron. Studies of thyroid pigment by Enochs and coworkers indicate that the pigment is a polymer due to the in vivo oxidation of minocycline by thyroid peroxidase, producing a melanin-like pigment.85 This pigment also contains significant amounts of iron, tightly bound in situ. A related phenomenon could well occur in the skin, in which case the drug metabolite could act as a reducing substance, explaining the frequent positivity with the Fontana-Masson stain.86 It is possible that minocycline may also stimulate melanin production, accounting for the diffuse “muddy brown” type III pigmentation, but further studies are needed to clarify this point. Minocycline pigmentation resolves after cessation of therapy, although this may be a very gradual process.84,87

Amiodarone is a therapeutic agent useful in treating certain cardiac dysrhythmias. It has long been known that this drug is a photosensitizing agent, on the basis of phototoxicity, triggered by ultraviolet B (UVB) as well as UVA light. In about 1% to 10% of individuals, a slate-gray pigment develops in sun-exposed sites, which are sometimes described as pseudocyanotic in appearance.88 The drug has high uptake in fatty tissues and a slow rate of elimination, resulting in persistence of the pigment. However, the pigmentation can slowly resolve after therapy has been discontinued,89 and it can be successfully treated with the Q-switched ruby laser.90 Although some authors believed the pigment represented lipofuscin, a “wear-and-tear” pigment composed of lysosome-derived lipids, sugars, and trace metals,91 early speculation that it might be, in effect, a storage disease composed of the drug or its metabolites88 has been supported by studies using energy dispersive x-ray microanalysis92 and high-performance liquid chromatography.93 The coexistence of lipofuscin with drug or a drug metabolite is also possible, as experience with clofazimine pigmentation suggests (see later discussion).

Clofazimine is a fat-soluble phenazine dye that has selective antimicrobial effects as well as anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties. It has been used to treat leprosy, including the reactional state erythema nodosum leprosum, chronic discoid lupus erythematosus, and other inflammatory dermatoses. A reddish blue pigment can develop in the skin in some cases, particularly within skin lesions for which the drug has been administered. Clofazimine crystals can be found in tissue and may be responsible,94 but lipofuscin pigment can also be identified, suggesting that the cutaneous changes may be due to ceroid lipofuscinosis.95 The pigment may persist for years but is considered reversible.95

Microscopic Findings

As generally described, there are differences among the microscopic features of the three major types of minocycline pigmentation. Type I (pigmentation in areas of inflammation or scar), with the dermal pigment present in macrophages, stains positively for iron in a manner similar to hemosiderin.78,96 Type II (blue-gray pigmentation of normal areas of the extremities and face) stains for iron and is also reactive with the Fontana-Masson method.97 Type III (diffuse, “muddy” brown) pigmentation has shown an increase in basilar melanin and brown-black pigment in macrophages that stains positively with Fontana-Masson and negatively for iron.98 However, staining results are not always distinctive among the three types. For example, type I pigmentation can stain positively both for iron and with the Fontana-Masson method99 (Fig. 12-11). Patients may also have more than one type of cutaneous minocycline pigmentation. Electron microscopy in cases with blue-gray or blue-black pigmentation has shown electron-dense particles in macrophages or extracellularly. Some intracytoplasmic granules are present within lysosomes, whereas other studies show fine, dustlike particles consistent with ferritin that are not bound by lysosomal membranes.84 Energy dispersive x-ray microanalysis has shown that the granules mostly contain iron, with lesser amounts of calcium.82,100

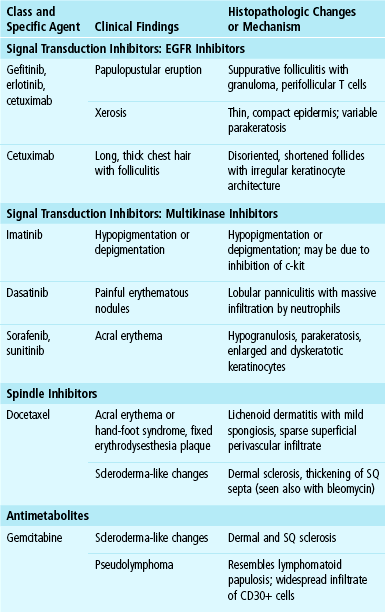

Figure 12-11 Minocycline pigmentation.

This occurred in a scar resulting from a biopsy of a relatively pigment-free melanocytic nevus. A, A hematoxylin and eosin–stained section showed pigmentation within the scar. The pigment stained for iron with Prussian blue (B) and was also positive with Fontana-Masson (C). The latter stain most often identifies melanin but more particularly results from the action of a reducing substance on ammoniated silver nitrate, which may not necessarily be melanin.

The Fontana-Masson staining method is routinely used to demonstrate the presence of melanin in tissue sections. Therefore, positivity in instances of minocycline pigmentation has suggested to some that melanin is at least partly responsible for the changes. This idea has been supported by one ultrastructural study showing melanosome complexes in siderosomes in a case of minocycline-related hyperpigmentation.100 However, melanosomes have not been identified in other studies.86 It is reported that iron may give positive staining reactions with Fontana-Masson.79 Furthermore, the black staining of Fontana-Masson results from the action of a reducing substance on ammoniated silver nitrate; that reducing substance is not necessarily melanin.86 The failure of the pigment to bleach suggests that the pigment in question does not contain melanin86 and lends additional support to the previously mentioned study on minocycline-induced thyroid pigment by Enochs and coworkers.85

Biopsies of the slate-gray pigmented areas caused by amiodarone have shown yellow-brown granules, sometimes refractile, within the reticular dermis (Fig. 12-12); these can be found within histiocytes, endothelial cells, and perivascular smooth muscle cells and between collagen bundles.88,101,102 Histochemical methods such as periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) and Fontana-Masson stain lipofuscin, but unfortunately they also stain other pigments, including (in the case of Fontana-Masson) melanin. Electron microscopy has shown intracytoplasmic granules, often but not invariably membrane-bound (presumably within lysosomes), that can have different appearances but are often described as “myelin-like.”101,102 In a more recent ultrastructural study, Ammoury and colleagues were not able to identify lipofuscin pigments93; their findings suggest a kind of storage disease due to drug (or drug metabolite) deposition.

Figure 12-12 Amiodarone pigmentation.

Yellow-brown pigment granules are identified within the reticular dermis.

Clofazimine pigment as been described as an amorphous, intraneural, alcohol- and acid-fast pigment with the staining characteristics of lipofuscin (in a patient with lepromatous leprosy),103 and by others as a ceroid-lipofuscin pigment within macrophages containing numerous phagolysosomes; these findings suggest a drug-induced “ceroid lipofuscinosis.”95 Using fluorescent microscopy, Kossard found red deposits around larger vessels in the dermis, corresponding to birefringent red crystals on fresh frozen sections. This suggests as direct role for clofazimine in producing the pigment changes.94 It may be that the drug itself and secondary ceroid or lipofuscin deposition both contribute to the pigmentation in varying degrees.

Differential Diagnosis

Minocycline pigmentation can be confused with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation due to melanin, hemosiderin deposition in inflammatory or hemorrhagic processes (including areas of trauma with scar formation), and other drug-induced pigmenting conditions. The pigment does not closely resemble the yellow-brown, refractile granules due to amiodarone or the vivid red deposits due to clofazimine. Chlorpromazine and other phenothiazines produce slate-gray pigmentation in sun-exposed areas. The dermal pigment deposits in these cases can resemble melanin but may also have a golden, refractile quality (probably representing the drug or its metabolite); melanin stains are positive but, unlike the case with minocycline, iron stains are negative. The pretibial slate-gray pigment seen with antimalarial therapy can stain for iron, melanin, or both, and therefore could be indistinguishable from minocycline deposition in the absence of a clinical history or more sophisticated laboratory methods.

The microscopic findings in amiodarone and clofazimine pigmentation could be confused with one another or possibly with similar changes due to other drug metabolites. Obviously, clinical history would be important in determining the responsible agent. Background changes in the lesion submitted for microscopic study would also be important; a lesion of lepromatous leprosy or discoid lupus erythematosus containing these types of pigments would certainly suggest clofazimine therapy. There could be a role for ceroid or lipofuscin in both conditions. However, the red deposits due to clofazimine, seen with fluorescent microscopy and in fresh frozen sections,94 appear to be relatively characteristic, and laboratory methods such as energy dispersive x-ray microanalysis and high-performance liquid chromatography could be used to identify amiodarone in tissue.93

Selected Pustular Drug Eruptions

Clinical Features

The unique halogen eruptions include bromoderma, iododerma, and fluoroderma.

Bromoderma, resulting as the name implies from ingestion of bromides, was at one time more common in the United States because of the widespread use of bromides as sedatives. This is no longer the case, and bromoderma is rarely encountered today. However, exposure to bromides still occasionally occurs, in the form of cough medicines (dextromethorphan hydrobromide), bronchodilators (ipratropium bromide), or uncommonly as additives to soft drinks.104 Overseas, a common use for bromides (in the form of potassium bromide) is in the treatment of multidrug-resistant seizures.105–107 The lesions present as pustular eruptions or as vegetative plaques and ulcers. As a characteristic feature, the vegetative plaques may show pustules along the periphery.106

Iododerma can develop following administration of iodides through a variety of methods: in the form of oral potassium iodide ingestion,108–110 from radioiodinated contrast materials,111 following topical112 or irrigation113 therapy with povidone-iodine, or due to dietary sources.114 Lesions are often pustular, but nodules, ulcers,110 or vegetative plaques108,115 also occur.

Fluoroderma is a rare condition. It consists of the development of papules and nodules after applying fluoride gel as prophylaxis for postirradiation dental caries.116

Microscopic Findings

All three eruptions tend to be neutrophil-rich; can feature neutrophilic microabscesses within the epidermis; are associated with extravasated erythrocytes; and (at least in bromoderma and iododerma) tend to show some folliculocentric involvement, at least in early lesions. Vegetative plaques show varying degrees of papillomatosis and pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, and dermal neutrophilic abscesses are also noted (Fig. 12-13). Other features include dermal edema, increased numbers of dilated vessels, and variable numbers of eosinophils. Although large macrophages may be apparent in older lesions117 (Fig. 12-14), in the author’s experience, granulomatous changes have not been a significant component of these lesions.

Differential Diagnosis

There is considerable overlap in the microscopic appearance of the three forms of halogenoderma, so that distinction among them requires additional clinical and laboratory information. On a percentage basis, at the present time, iododerma seems to be the most common of these eruptions. Early or isolated pustular lesions prompt a consideration of other pustular diseases, including forms of pustular folliculitis. The combination of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia and neutrophilic microabscesses also raises the consideration of infection-related lesions with a blastomycosis-like tissue reaction pattern, including deep fungal infections, blastomycosis-like pyoderma, or some atypical mycobacterial infections. A significant granulomatous component favors one of the latter conditions, and therefore special stains for organisms and culture studies may be warranted. Lesions of pemphigus vegetans could have overlapping microscopic features, but in the latter disease, the intraepidermal abscesses are composed of eosinophils, and a careful search may reveal acantholytic changes.

Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis

The first report of a condition bearing the name acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) appeared in the French literature in 1985,118 and an important review was published in 1991.119 AGEP presents as numerous pinpoint pustules on an erythematous, edematous base, associated with fever and leukocytosis.120,121 Lesions are prone to develop in body folds and on the face.122 There is a strong association with medications, but the condition has also been associated with certain enteroviruses,123 mercury,119 or ultraviolet radiation.120 Among the medications, antimicrobials as a group have always been considered leading triggering factors. Based on frequency of citations, the most common eliciting drugs are diltiazem, amoxicillin, terbinafine, acetaminophen, and hydroxychloroquine. The eruption of AGEP typically shows rapid onset, usually within several days of initiation of the offending agent, and resolves within two weeks of discontinuing the offending drug.121 There is a history of psoriasis in a minority of patients, but the appearance and time course of the eruption are not typical for that disorder. The process may be T-cell mediated, as suggested by positive patch testing, isolation and propagation of drug-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and high production by these cells of CXCL8, a neutrophil-attracting chemokine.124

Microscopic Findings

Features of AGEP include subcorneal or intraepidermal pustules, usually fairly small in size, with a mild degree of adjacent spongiform pustulation122 (Fig. 12-15). Other findings include scattered necrotic (apoptotic) keratinocytes,125 papillary dermal edema, and occasionally changes sufficient to suggest a small vessel vasculitis. Eosinophils can also be identified.122

Differential Diagnosis

The small size of the intraepidermal pustules, together with apoptotic keratinocytes, eosinophils, and minor vasculitic changes, is strongly suggestive of AGEP. The pustules of pustular psoriasis are usually larger and show more prominent spongiform pustulation, whereas the degrees of acanthosis in AGEP are generally less than would be expected in fully developed plaque-type psoriasis. Infection with Candida or a dermatophyte could show overlapping features, but PAS or silver methenamine stains would be positive for microorganisms. Despite an occasional clinical resemblance to erythema multiforme, pustules are generally not observed in the latter disease, whereas apoptosis is usually more extensive than in lesions of AGEP. Pustulosis acuta generalisata is an eruption due to upper respiratory streptococcal infection. It can also present as an acute, widespread eruption and may have eosinophils in the dermal infiltrate126; however, the intraepidermal pustules tend to be larger, and there is usually a more obvious underlying leukocytoclastic vasculitis.127,128

Selected Reactions to Metals

Clinical Features

These reactions include argyria, chrysiasis, and hydrargyriasis.

Argyria typically presents as a slate-gray–blue pigmentation, especially on sun-exposed sites. Mucosal and nail pigmentation also occurs, the latter representing a bluish discoloration of the proximal portion or lunulae of the nails (azure lunulae).129 The cause is prolonged ingestion of silver salts or repeated application to mucous membranes, but this may occur in a variety of ways that can be quite unusual: drinking (repeatedly) from a silver goblet, using certain dietary supplements,130 chewing photographic film,131 or having an impacted earring.132

Chrysiasis is characterized by slate-blue discoloration in sun-exposed sites in individuals treated with gold salts (e.g., sodium aurothiomalate) for rheumatoid or psoriatic arthritis.133–135 Reddish purple corneal deposits are also seen in these patients, but these do not appear to contribute to visual impairment.136,137 Local blue-gray discoloration has also developed immediately after treatment with the Q-switched ruby laser, when administered to individuals receiving parenteral gold therapy.138 On the other hand, improvement of pigment changes due to chrysiasis has been described with the pulsed dye laser.139 The amount of gold deposition in skin is greater in sun-exposed sites and correlates with the degree of pigmentation.140 In addition, there may be a role for increased melanin production in hyperpigmented areas.134

Hydrargyriasis (mercury exposure) can also produce a slate-gray pigmentation of the skin. This can result from the use of skin-lightening creams or soaps and is mostly encountered in Third World countries.141,142 It has also been associated with industrial exposure.143 Changes due to topical mercury are often noted on the eyelids and nasolabial folds.144

Microscopic Findings

In argyria, fine silver granules are deposited along basement membranes, particularly around sweat glands but also occasionally along the epidermal basement membrane. They can also be identified diffusely in the dermis (especially in dermal papillae), around hair follicles, in nerves, and associated with elastic fibers.145 Increased amounts of melanin may also be found in the epidermis or in the superficial dermis. The silver deposits can be dramatically demonstrated with darkfield microscopy, in which the particles are brightly refractile145 (Fig. 12-16). In chrysiasis, small black granules are found within dermal macrophages. They are refractile with darkfield examination, but in addition, evaluation with cross-polarized light shows a characteristic orange-red birefringence.146 Electron microscopic study shows amorphous or spherical deposits, the latter appearing in lysosomes.135 X-ray microanalysis can confirm the presence of gold.133 Mercury pigment appears as brown-black granules, found free in the dermis or within macrophages.147 As is the case for silver, mercury granules are brightly refractile on darkfield microscopy.148 With electron microscopy, dense 400- to 900-nm aggregates of 12-nm particles are identified in macrophages and free within the dermis.143 Again, x-ray microanalysis can be used to positively identify the presence of mercury.

Figure 12-16 Argyria.

A, Fine black silver granules can be seen associated with fine elastic fibers in the superficial dermis. Increased basilar melanin pigmentation is also observed. B, Fine granular silver deposits can be seen along basement membranes of eccrine sweat glands. C, Darkfield microscopy, which shows brightly refractile silver deposits around the sweat glands.

Differential Diagnosis

The appearance of the characteristic granules separates the pigmentation caused by deposition of these heavy metals from that due (1) purely to melanin (e.g., post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, melasma, or dermal melanocytoses) or (2) to pigment-producing drugs such as minocycline, phenothiazines, or antimalarials, which may variably include melanin, a melanin-like drug metabolite, or iron. With light microscopy, it may be difficult to distinguish among gold, silver, and mercury deposits. All are refractile on darkfield microscopy. However, there are differences. Gold granules are larger and more irregular than those of silver and are found predominantly within macrophages.149 Silver particles are largely extracellular and tend to be deposited on basement membranes, around vessels, and on elastic fibers. Mercury granules are also found most commonly in macrophages, or occasionally in the epidermal basilar layer. The orange-red birefringence of gold particles with cross-polarized light may be a unique feature. Further distinction can be made with ultrastructural study, based on not only the distribution but also on the relative size of the granules (gold larger than silver larger than mercury) and their aggregation properties. If necessary, x-ray microanalysis and related methods can provide definitive identification of the material.

Drug-Induced Pseudolymphoma

Clinical Features

It is now well known that certain medications can produce skin lesions that clinically and microscopically closely resemble lymphoma. These lesions can even produce immunophenotypic abnormalities and positive T-cell receptor gene rearrangement studies. This constellation of findings has led to the alternative term drug-induced reversible lymphoid dyscrasia.150 Clinically, the best-known manifestations are cutaneous plaques, resembling those of mycosis fungoides, but papules, nodules, and lesions resembling either pityriasis lichenoides or pigmented purpura also occur. Lesions may develop in the context of a drug hypersensitivity syndrome, including drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS),151 and lymphadenopathy may be part of the picture. Drug classes and specific agents that are associated with pseudolymphoma resembling mycosis fungoides include antiseizure medications, phenothiazines, antihistamines, fluoxetine, amitriptyline, barbiturates, beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Other agents promoting pseudolymphoma include lipid-lowering agents, thiazides, and other antidepressants.152

Microscopic Findings

Much of the published information about the mechanisms and histopathology of drug-induced pseudolymphoma derives from the work of Magro, Crowson, and associates.150,153–155 Lesions resembling mycosis fungoides feature a superficial band-like dermal infiltrate with variable degrees of epidermotropism and atypical lymphoid cells.154 Nodular lesions can resemble lymphocytoma cutis (Fig. 12-17), complete with zonation of B cells resembling lymphoid follicles. Papular lesions variably display the image of an angiocentric lymphoproliferative disorder or the changes of follicular mucinosis.154 A configuration similar to that of atypical pigmented purpura can also be seen, and the dermal infiltrates contain CD30-positive cells.152,156 The interstitial granulomatous drug reaction (see Chapter 13) bears some microscopic resemblance to granulomatous mycosis fungoides and is produced by many of the same agents responsible for other forms of drug-induced pseudolymphoma.152

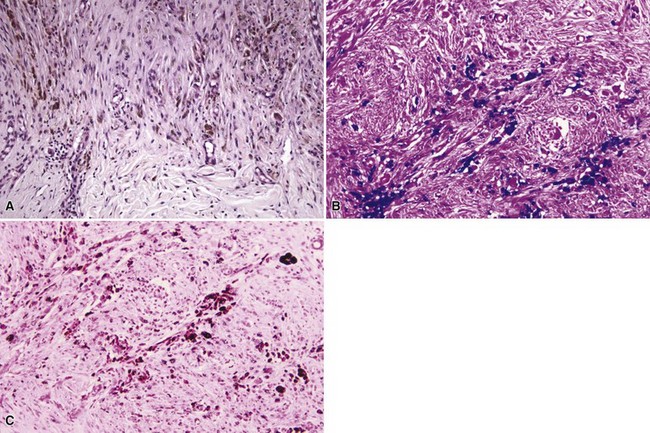

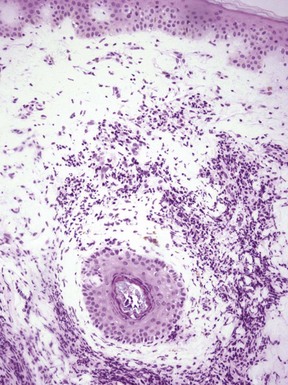

Figure 12-17 Drug-induced pseudolymphoma.

A, Dense dermal lymphocytic infiltrate with prominent vessels. B, A higher power view also shows plasma cells and numerous eosinophils.

The immunophenotype of drug-induced pseudolymphomas resembling mycosis fungoides can vary, ranging from a normal CD4 : CD8 ratio and no CD7 “dropout” to a high CD4 : CD8 ratio with loss of CD7 or CD62L (L-selectin).157 Loss of CD7 and CD62L expression may reflect the properties of a reactive cell population engaged in a type IV immune process, rather than an expression of clonality.158 Occasionally, CD8 predominance can be seen in drug-related cases, just as can occur in some examples of mycosis fungoides.150 Clonality in T-cell pseudolymphoma has been observed, with a molecular profile resembling that of mycosis fungoides.152 Examples of both B-cell and T-cell “pseudoclonality” have been found in a series of cutaneous pseudolymphoma cases.159

Differential Diagnosis

A diagnosis of drug-induced pseudolymphoma requires a certain index of suspicion, and therefore any unusual dermal lymphoid infiltrate should raise this possibility. A review of the patient’s medications is thus worthwhile, because discontinuation of potential triggering agents might result in clearing of the lesions. However, resolution may be a slow process, sometimes taking 6 months or more.154 Certainly, drug is a known cause for lymphocytoma cutis. Regarding those lesions that resemble mycosis fungoides, distinction may be difficult on morphologic grounds. However, the intraepidermal lymphocyte population is generally less atypical than that in the dermis—a reversal of the usual situation in mycosis fungoides.154 As noted, CD7 and CD62L loss can be seen in drug-induced pseudolymphoma, and because monoclonality can also be identified in a high percentage of cases, these laboratory procedures may not allow for a clear distinction between pseudolymphoma and true mycosis fungoides. There is also considerable histopathologic overlap among atypical pigmented purpura due to drugs, idiopathic pigmented purpura, and mycosis fungoides–related pigmented purpura. Intraepidermal lymphocytes that are more atypical than those in the dermal infiltrate favor mycosis fungoides–related pigmented purpura over the other two types.156

Dermatoses Caused by Physical Agents

Disorders Caused by Ultraviolet Injury

Clinical Features

Several different disorders can be directly traced to a response to ultraviolet exposure.

Polymorphic light eruption is considered the most common photodermatosis.160 It has a worldwide distribution,161 is most common in females,162 and tends to arise in early adult life. Lesions consist of papules, papulovesicles, and plaques involving sun-exposed areas. These develop within several hours of sun exposure and last for about 2 weeks.160 There is a tendency for the eruption to develop with early sun exposure, usually in the spring, with improvement or “hardening” of the skin occurring later in the year. UVA light is considered most responsible, but there is also a role for UVB and possibly visible light. Although the cause is not completely understood, polymorphic light eruption is considered by many to represent a type IV, cell-mediated immune response.163 Several phototesting methods have been developed, mostly designed in an attempt to replicate natural ultraviolet exposure.164,165 Treatments include sunlight avoidance or desensitization phototherapy,166 use of sunscreens, and drug therapy ranging from antimalarials to azathioprine.

Actinic prurigo (hydroa aestivale) is considered by some to be a related dermatosis, but there are some distinct differences. This condition occurs most commonly among Native American populations of North and Central America, with sporadic cases reported from Australia and elsewhere.167 The onset is frequently in childhood and consists of markedly pruritic papulovesicles and cheilitis; the latter may be the only clinical manifestation.168 In contrast to polymorphic light eruption, hardening through the summer does not occur, and light testing is not predictable.169 Although improvement can occur over a period of years, the condition can be quite disabling. Thalidomide appears to be particularly effective in these cases.170

Hydroa vacciniforme is an unusual photodermatosis that begins in childhood. Following sun exposure, erythema is followed by the formation of deep-seated vesicles, sometimes in crops, over the nose, cheeks, forearms and hands. These lesions become necrotic and heal with varioliform scars.171,172 Spontaneous clearing can occur over a period of 5 to 10 years. Testing with UVA light (using monochromatic light or repetitive exposure) can elicit the lesions. Treatment includes use of broad-spectrum sunscreens or narrow-band UVB exposure.173,174 A subset of patients with lesions resembling hydroa vacciniforme develop T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders,175–177 and these can be shown to have latent Epstein-Barr virus infection.178

Chronic actinic dermatitis is the term most commonly used for a set of chronic photosensitive dermatoses. These conditions have individually been described as persistent light reactivity (dermatitis that persists despite discontinuation of the original photosensitizing agent); photoaggravated eczema; and a condition that closely mimics T-cell lymphoma, actinic reticuloid.179 Middle-aged or elderly men are particularly likely to present with this condition. Findings consist of eczematous lesions that occur in the setting of photosensitivity but without exposure to known photosensitizing agents. In the more severe form of the disease, termed actinic reticuloid, plaques or erythroderma may develop, raising the specter of mycosis fungoides or Sézary syndrome.180 Patch testing and photopatch testing are sometimes positive, and contact sensitivity to sesquiterpene lactone, a constituent of plants of the Compositae family (e.g., ragweed) is common, even though this allergen does not act directly as a photosensitizing agent. Testing with monochromatic UVA light may be a useful diagnostic procedure, because an isolated UVA response favors drug-induced photosensitivity, whereas individuals with chronic actinic dermatitis tend to be photosensitive to UVA and UVB and sometimes to visible light.181 The condition may be quite persistent.182 However, it may respond to treatment with sunlight and allergen avoidance, topical corticosteroids, topical tacrolimus, or systemic immunosuppressive therapy.183–185

Microscopic Findings

Polymorphic light eruption shows variable degrees of spongiosis; papillary dermal edema; and a distinctly perivascular, superficial and deep dermal infiltrate composed mainly of lymphocytes and a few macrophages186,187 (Fig. 12-18). Interface dermatitis, manifesting as vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer, is not a change the authors associate with polymorphic light eruption, and this agrees with the findings of others.188 The lymphocytic infiltrate is composed predominantly of T cells.189 Rijlaarsdam and coworkers found that the cells in the dermal infiltrate express CD62L (leu8) but not human leukocyte antigen-DR (HLA-DR).190

Figure 12-18 Polymorphic light eruption.

This lesion shows marked dermal edema and a superficial and deep perivascular infiltrate composed predominantly of lymphocytes. There is also perifollicular accentuation of the infiltrate in this example.

Early lesions of actinic prurigo show spongiosis, papillary dermal edema, and a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, thereby closely resembling polymorphic light eruption.191 Although vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer is also described, this may simply be an accompaniment of spongiosis and/or dermal edema, and the changes are not convincing for a primary interface or lichenoid dermatitis. Later biopsies are said to show hyperkeratosis, acanthosis with elongated rete ridges, and dermal findings consistent with repair of tissue injury191; these must be regarded as nonspecific and representative of chronic spongiotic dermatitis or lichen simplex chronicus. Some biopsies show only the consequences of prurigo: erosion or shallow ulceration, neutrophils in the immediate vicinity, and dermal fibrin deposition (Fig. 12-19). The cheilitis of actinic prurigo also shows acanthosis, spongiosis, sometimes serous crusting, edema of the lamina propria, and a characteristic lymphocytic infiltrate with well-defined lymphoid follicles, together with some eosinophils and melanophages.168

Figure 12-19 Actinic prurigo.

This example shows nonspecific changes of a shallow ulcer, neutrophils, and fibrin deposition. The clinical history is crucial to establish the correct diagnosis in such cases.

Hydroa vacciniforme shows an intraepidermal vesicle with reticular degeneration, underlying hemorrhage and sometimes thrombosis, and homogeneous epidermal necrosis174,192 (Fig. 12-20). Cases evolving into a picture of T-cell lymphoma can show dense lymphoid infiltrates in the dermis and subcutis, sometimes with striking cytologic atypia.175,176 In a large study by Iwatsuki and colleagues, T cells containing Epstein-Barr virus–encoded small nuclear RNA were found in the infiltrates of 28 of 29 patients, representing a spectrum of involvement ranging from typical photosensitive hydroa vacciniforme to severe disease. Five patients in the latter group died of Epstein-Barr virus–related natural killer (NK)-/T-cell lymphoma or a hemophagocytic syndrome.193

Figure 12-20 Hydroa vacciniforme.

A, Reticular degeneration and necrosis of the epidermis is evident. There are underlying hemorrhage and a rather dense patchy lymphocytic dermal infiltrate. B, A higher power view shows epidermal vesiculation and necrosis.

The features of chronic actinic dermatitis may vary, depending on the duration and category of the eruption. Changes in persistent light reaction or photosensitive eczema are similar to those of photoallergic drug reaction. They include spongiosis, a substantial perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate with variable numbers of eosinophils, and lymphocyte exocytosis194 (Fig. 12-21). Granulomatous changes developed in one case of chronic actinic dermatitis that was studied over a 2-year period.195 In actinic reticuloid, there is a dense bandlike subepidermal infiltrate composed mainly of lymphocytes, some having convoluted nuclei. Migration of these cells into the epidermis can be accompanied by structures resembling Pautrier microabscesses196,197 (Fig. 12-22). There is a low CD4 : CD8 ratio among lymphocytes,180,198 and the number of beta-chain constant region of the T-cell receptor (BF1)–positive cells is approximately the same as that of CD3-positive cells.199

Differential Diagnosis

Polymorphic light eruption has a characteristic set of microscopic features, but the variability of the epidermal changes can resemble other inflammatory dermatoses, particularly forms of eczematous dermatitis. In addition, the superficial and deep dermal lymphocytic infiltrates can mimic those of lupus erythematosus, lymphocytoma cutis, and lymphocytic infiltration of Jessner. Interface changes (when present) argue most strongly for lupus erythematosus, whereas significant dermal mucin deposition and periadnexal infiltrates favor either lupus erythematosus or lymphocytic infiltration of Jessner. Unfortunately, studies of lymphocyte subpopulations do not allow a clear distinction among these dermatoses,190 with the exception of a significant B-cell component in lymphocytoma cutis.189 The changes of actinic prurigo are generally nonspecific, resembling those of other eczematous dermatoses with accompanying erosion and crusting. However, lymphocytic aggregates with germinal center formation in the context of spongiotic change may be characteristic of the cheilitis associated with actinic prurigo. Hydroa vacciniforme has the reasonably specific findings of intraepidermal vesiculation with reticular degeneration and eosinophilic epidermal necrosis. However, careful attention should be paid to the dermal infiltrate because of the known association with T-cell lymphoma. Further studies may be necessary to confirm the strong association with Epstein-Barr virus infection found in the studies of Iwatsuki and others.

Examples of chronic actinic dermatitis showing spongiotic changes would be difficult to distinguish from other forms of eczematous dermatitis, including photoallergic dermatitis due to topically or systemically administered photosensitizers. Clinical history is important, as is light testing, because sensitivity restricted to monochromatic UVA light suggests drug-induced photosensitivity. The histopathology of lesions in the actinic reticuloid end of the spectrum can closely resemble mycosis fungoides or Sézary syndrome, but the demonstration of photosensitivity, predominance of CD8-positive cytotoxic cells both in blood and skin, and the lack of evidence for clonality on gene rearrangement study all argue for chronic actinic dermatitis of the actinic reticuloid type.

Disorders Caused by Other Physical Agents

Several disorders caused by physical agents include thermal burns, erythema ab igne, radiation dermatitis, and calcaneal petechiae.

Thermal burns are rarely biopsied because the source of the injury is frequently apparent, but biopsy may sometimes be necessary, particularly if the patient has no recollection of the burn or if there is suspicion for another abnormality, such as bacterial infection or an immunobullous disease. Burn injuries are common among elderly individuals, and survival appears to have improved in recent years.200 First-degree burns present mainly as erythema, although there may also be some superficial desquamation. Second-degree burns are often divided into two categories: superficial second-degree burns are associated with blanching erythema and vesicle formation, and deep second-degree burns have areas of pallor as well as nonblanching erythema. Pain can be severe. In third-degree burns, where damage occurs through the full thickness of the dermis, the skin has a whitish or charred appearance. Secondary blisters can develop in previously burned sites, probably as a result of minor injury in the face of defective basement membrane zone reorganization following the initial burn injury.201

Erythema ab igne results from prolonged or repetitive exposure to heat of moderate degree, and consists of reticulated erythema that often becomes pigmented. A variety of colors may be present, reflecting combinations of old and active lesions. Exposure to radiators, heating pads, fireplaces, or other devices can serve as the sources for this type of heat injury. The condition may gradually improve with discontinuation of the heat exposure.

Radiation dermatitis can occur in several stages. In acute radiation dermatitis, erythema and edema predominate; severe acute changes are less common, given modern methods of fractionated doses. Subacute radiation dermatitis occurs some weeks to several months following radiation exposure and can present as persistent erythema in treatment sites or as poikilodermatous change.202 Chronic radiation dermatitis develops months to years after radiation exposure, and (depending on the severity of injury) can present as poikilodermatous areas (atrophy and variegated pigmentation) or ulcers. Squamous cell carcinomas, sarcomas, and (uncommonly) basal cell carcinomas can develop in areas of chronic radiation dermatitis.203–206 Radiation recall dermatitis describes inflammation in an area that had been previously irradiated, induced usually by a chemotherapeutic agent,207,208 although it has also been associated with other therapeutic agents, such as antimicrobials.209 The inflammatory changes usually resolve several days after discontinuing the causative medication.210 An unusual reaction to radiation therapy has been termed eosinophilic, polymorphic, and pruritic eruption. This change can arise during or after radiotherapy for malignancy (particularly breast carcinoma), and presents as an eruption of excoriations, papules, vesicles and bullae in the treated site.211,212

Calcaneal petechiae, also known as black heel and talon noir, consist of hyperpigmented macules, sometimes speckled, typically occurring as the result of a jamming injury to the heel; other body surfaces can show the same changes following similar types of injury. Often the original injury is forgotten, and the patient or his or her physician may be alarmed by the sudden appearance of black macules, raising concerns about possible melanoma.

Microscopic Findings

First-degree burns show some degree of necrosis limited to the superficial portion of the epidermis. In superficial second-degree burns, superficial epidermal necrosis, sometimes subepidermal blister formation, and degeneration of superficial dermal collagen are characteristic. In deep second-degree burns, there is more extensive degenerative change of connective tissue, involving the reticular dermis and with necrosis of portions of the cutaneous appendages. In third-degree burns, there is connective tissue degeneration involving the full thickness of the dermis and sometimes involving deeper structures; there is also complete loss of the appendages213 (Fig. 12-23). A histomorphologic scale has been developed to quantify the extent of cutaneous scarring associated with burn injury.214

Figure 12-23 Third-degree burn.

There are epidermal necrosis, connective tissue degeneration involving the full thickness of the dermis, and a complete loss of appendages. Note the hyalinized changes around vessels in the deep dermis.

Erythema ab igne shows epidermal atrophy, vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer, edema, and dermal pigment deposition.215 Several authors have noted an increase in dermal elastic tissue.215,216 Keratinocyte atypia can be observed (Fig. 12-24). In addition, both keratoses and squamous cell carcinoma in situ have been described,217 resembling to some degree the changes occurring with actinic damage.

Figure 12-24 Erythema ab igne.

Findings include vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer, dermal pigment deposition, and prominence of elastic tissue with a resemblance to solar elastosis. Basilar keratinocyte atypia can be seen in the central portion of the image.

The findings of acute radiation dermatitis include degenerative changes of the epidermis and appendages, with intracellular edema and pyknosis of nuclei (Fig. 12-25); this correlates with findings in an ultrastructural study of acute radiation injury, which included cytoplasmic vacuolization and perinuclear aggregation of tonofibrils.218 Dermal inflammation, vasodilatation, and proliferation of endothelial cells have also been described.219 Subacute radiation dermatitis shows interface dermatitis, with vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer; some cytologically atypical keratinocytes; numerous dyskeratotic (apoptotic) keratinocytes; and a lymphocytic infiltrate with aggregation of lymphocytes around dyskeratotic cells, representing “satellite cell necrosis”202 (Fig. 12-26). The epidermis in chronic radiation dermatitis can show variable atrophy and acanthosis, sometimes with disorganization of keratinocytes and atypical nuclei. Sclerosis and hyalinization of dermal collagen may occur, with loss of hair follicles and sebaceous glands, although eccrine glands may be preserved. There is thickening of the walls of deep dermal vessels, sometimes with luminal occlusion. Large and atypical spindled cells (radiation fibroblasts) are frequently observed and can be of great diagnostic importance220 (Fig. 12-27). The histopathology of radiation recall dermatitis appears not to have been well described with regard to the acute changes. However, deep sclerosis of collagen in the dermis and subcutis has been reported, probably the result of the original radiation therapy.221 In one case, the subcutaneous changes resembled those of lipodermatosclerosis (see Chapter 7) and may have resulted from small vessel injury.222 In the uncommon eosinophilic, polymorphic, and pruritic eruption associated with radiation therapy, there is a superficial and deep perivascular infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and eosinophils (Fig. 12-28). Eosinophils may be observed within the epidermis or in the subcutis, associated with eosinophilic panniculitis. Immunohistochemistry has shown a slight CD4 predominance and perivascular IgM and C3 deposits.212

Figure 12-25 Acute radiation dermatitis.

The epidermis shows slight intracellular edema, and pyknosis of nuclei can be observed both in epidermis and follicular epithelium. Dermal inflammation is apparent.

Figure 12-26 Subacute radiation dermatitis.

Findings include interface dermatitis, with vacuolar alteration of the basilar layer, some keratinocyte atypia, apoptotic keratinocytes, and a lymphocytic infiltrate with exocytosis.

Figure 12-27 Spectrum of findings in chronic radiation dermatitis.

A, Epidermal atrophy and sclerosis occur, with hyalinization of dermal collagen and loss of follicular units. B, This example shows acanthosis with disorganization and focal atypia among basilar keratinocyte nuclei. C, Thickening of the walls of deep dermal vessels occurs. D, Radiation fibroblasts are apparent.

Figure 12-28 Eosinophilic, polymorphic, and pruritic eruption.

Prominence of superficial dermal vessels, with a perivascular lymphocytic and eosinophilic infiltrate. This image was obtained near the base of an ulcer, explaining the presence of neutrophils.

Calcaneal petechiae show red-yellow hemorrhagic deposits within the stratum corneum and sometimes erythrocyte extravasation in the dermal papillae (Fig. 12-29). This phenomenon is often regarded as an example of transepidermal elimination, in which blood and blood products are slowly extruded to the epidermal surface.223,224

Differential Diagnosis

First-degree burns are rarely biopsied, but the superficial epidermal necrosis seen in these lesions could mimic necrosis resulting from chemical agents or, possibly, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome. Second-degree burns with blisters should be distinguished from other infiltrate-poor subepidermal blistering disorders, although the degree of underlying connective tissue degeneration is a clue to the cause. Electrical injury can have overlapping features, but the prominent elongation of the cytoplasm of basilar keratinocytes point toward electrical injury. Purposeful electrical injury (e.g., due to electrodesiccation or use of cutting current in surgical procedures) can usually be distinguished by the confinement of connective tissue degeneration to a more-or-less regular subepidermal band or to the surgical margins of a larger excisional specimen. Erythema ab igne has features that overlap with other interface dermatoses with poikilodermatous features. However, the increased amounts of dermal elastic tissue constitute a distinctive feature, which in turn can be separated from solar elastosis by the lack of homogenization or of basophilia on hematoxylin and eosin–stained sections.

Subacute radiation dermatitis also shows changes of interface dermatitis and can be a close mimic of graft-versus-host disease.202 As pointed out by LeBoit in his paper on this topic, cytologic atypia is not in itself a feature of graft-versus-host disease but can be seen in combination with chemotherapy effects. In addition, lymphocytic infiltrates may be moderately dense in subacute radiation dermatitis, which can overlap with the findings in acute graft-versus-host disease.202 Therefore, clinical correlation is essential in these cases. Numerous conditions are characterized by sclerosis of dermal collagen and could therefore be confused with chronic radiation dermatitis. Examples include morphea/scleroderma and scars due to other causes, including thermal injury. However, the large, atypical radiation fibroblasts are quite characteristic of chronic radiation injury. In addition, arrector pili muscles and (often) eccrine sweat glands are preserved in chronic radiation dermatitis, whereas these structures are destroyed in deep thermal burns.225 Eosinophilic, polymorphic, and pruritic eruption is often a surprising change in the context of prior irradiation therapy. The differential diagnosis includes other causes of eosinophilic dermatitis and panniculitis: reaction to drug or arthropod, Wells syndrome, the eosinophilic panniculitis that clinically mimics erythema nodosum, injection therapies, vasculitis with eosinophils, or lymphoproliferative disorders. The clinical history is therefore key in these cases.

The changes in calcaneal petechiae are characteristic, but they could be overlooked or dismissed as nonspecific secondary change in tissue caused by prior trauma. This is especially likely when, as is often the case, the clinical impression is to rule out melanoma, and therefore the focus is on detection of a melanocytic lesion.

References

1. Cohen, AD, Friger, M, Sarov, B, et al. Which intercurrent infections are associated with maculopapular cutaneous drug reactions? A case-control study. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:41–44.

2. Dascalu, DI, Kletter, Y, Baratz, M, et al. Langerhans’ cell distribution in drug eruption. Acta Derm Venereol. 1992;72:175–177.

3. Fellner, MJ, Prutkin, L. Morbilliform eruptions caused by penicillin. A study by electron microscopy and immunologic tests. J Invest Dermatol. 1970;55:390–395.

4. Ackerman, AB. Superficial perivascular dermatitis; some morbilliform drug eruptions. Histologic Diagnosis of Inflammatory Skin Diseases. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1978. [196-197].

5. Kitamura, K, Aihara, M, Osawa, J, et al. Sulfhydryl drug-induced eruption: a clinical and histological study. J Dermatol. 1990;17:44–51.

6. Terui, T, Tagami, H. Eczematous drug eruption from carbamazepine: coexistence of contact and photocontact sensitivity. Contact Dermatitis. 1989;20:260–264.

7. Yawalkar, N, Hari, Y, Helbing, A, et al. Elevated serum levels of interleukins 5, 6, and 10 in a patient with drug-induced exanthem caused by systemic corticosteroids. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:790–793.

8. Marra, DE, McKee, PH, Nghiem, P. Tissue eosinophils and the perils of using skin biopsy specimens to distinguish between drug hypersensitivity and cutaneous graft-versus-host disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:543–546.