Infectious Diseases, Including Infestations and Parasitic Diseases

This chapter will consider the histopathologic findings of a wide variety of infectious diseases and infestations, including those disorders caused by bacteria, fungi, viruses, arthropods and other parasites, and protozoa. Dermatopathology can play an important role in the diagnosis of these disorders in several ways. First, it may be possible to identify the infectious agent in tissue sections, using either routine staining (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E]) or special stains. The sensitivity of histopathologic analysis for infection has improved over the years with the introduction of immunohistochemical staining for identification of organism proteins or genetic material (through in situ hybridization). These methods can be further enhanced by systematic search for specifically stained infectious agents using techniques such as focus-floating microscopy.1,2 However, it is not always possible to find organisms in tissue sections using current methods. Second, histopathology may help find indirect clues to infection. These include such changes as pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, abscess formation, suppurative granulomas, thromboembolic changes, or unexplained necrosis and connective tissue degeneration. These and other findings can trigger tissue culture studies, serologic evaluations, or other methods that may prove to be more successful. Still, it is impressive how often skin biopsy can yield a specific diagnosis of an infectious disease, even in the absence of supporting culture studies. This chapter is not by any means designed to be a complete review of all infectious disease, but it does focus on those infections that have relatively characteristic biopsy findings and are likely to be either actually encountered in clinical practice, or to become serious considerations in the histopathologic differential diagnosis.

Bacterial Diseases

Clinical Features: Impetigo is a superficial skin infection produced most often by staphylococci (particularly Staphylococcus aureus) but also by streptococci or a combination of the two. It is most common in children but also occurs in adults. In some instances, it may develop as a complication of allergic contact dermatitis. Erythematous macules evolve into thin-walled vesicles and bullae. These rupture and drain, producing a characteristic “honey-colored” crust. Infection with group A β-hemolytic streptococci can lead to acute glomerulonephritis in approximately 1% of cases.3 Streptococcal impetigo has a significant incidence in patients with atopic dermatitis.4 A variant called Bockhart impetigo presents as a superficial pustular folliculitis in hair-bearing areas; it may be complicated by superficial trauma or occlusion in the setting of S. aureus colonization.5

Microscopic Findings: A vesicle develops in the vicinity of the granular cell layer of the epidermis. When it is fully developed, it often appears in a subcorneal location. Neutrophils accumulate within the vesicle, forming a vesicopustule (Fig. 17-1). A minor degree of acantholysis can be identified at the base of the pustule, resulting from the effect of neutrophilic proteolytic enzymes, and evidence of degenerated keratinocytes has been found on ultrastructural examination.6 An upper dermal infiltrate often consists of a mixture of neutrophils and lymphocytes. Following rupture of the bulla, a surface crust is formed that is composed of transudated serum and degenerated neutrophils. Gram-positive cocci can sometimes be found within the vesicopustule.7 Bockhart impetigo shows a subcorneal vesicopustule at the follicular orifice.

Differential Diagnosis: Subcorneal pustule formation can also be identified in subcorneal pustular dermatosis and pemphigus foliaceus. However, the finding of bacteria in the vesicopustule points to a diagnosis of impetigo. Pemphigus foliaceus usually shows fewer neutrophils and a greater degree of acantholysis, often with evidence of dyskeratosis. Pustular psoriasiform dermatoses, including Reiter syndrome, candidiasis, and geographic tongue, in addition to psoriasis, ideally show spongiform postulation in the superficial portions of the spinous layer—a feature not typically seen in impetigo. Candidal organisms are of course expected in the pustular lesions of candidiasis. Immunoglobulin A (IgA) pemphigus of the subcorneal pustular dermatosis type uniquely shows intercellular IgA deposition on direct immunofluorescence examination. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis tends to feature smaller superficial pustules and may have the additional changes of apoptosis, underlying leukocytoclastic vasculitis, or a dermal infiltrate that includes eosinophils.

Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome

Clinical Features: This generalized exfoliative erythroderma is seen most often (by far) in young children but also encountered in immunosuppressed adults.8,9 It typically begins with fever and erythema in intertriginous sites, with sheetlike exfoliation following rapidly thereafter. The eruption is due to an exfoliative toxin produced by group 2 S. aureus, especially phage types 55 and 71.10,11 Antimicrobial therapy (typically with penicillins that are penicillinase-resistant) is usually successful, and most cases in children have a good prognosis.

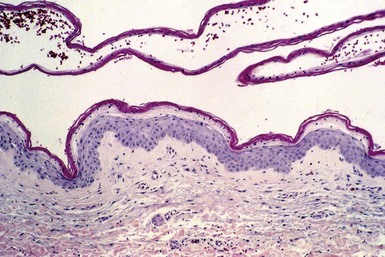

Microscopic Findings: There is a separation below or within the granular cell layer of the epidermis; the exfoliating portion of epidermis has a necrotic appearance (Fig. 17-2). Inflammation is minimal. Bacteria are generally not identified, since the changes result from the effects of the circulating toxin. The actual focus of infection most often involves mucosal surfaces, including oral or nasal cavities.

Differential Diagnosis: The lesions must be differentiated from toxic epidermal necrolysis, in which there is full-thickness epidermal necrosis. This differentiation can be made rapidly using frozen sections or rapid processing of exfoliated skin, because staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome shows only superficial epidermal necrosis. Similarly, bullous impetigo can often be distinguished from early staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, because neutrophils are frequently present, organized as subcorneal pustules. The separation that occurs in this syndrome is at the same level of the epidermis as pemphigus foliaceus; the exfoliative toxins act on desmoglein 1, the antigenic target of that form of pemphigus.12 However, the relative lack of inflammation and characteristic clinical setting of staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome allow distinction in most cases. In more difficult circumstances, direct immunofluorescence is decisive, because only pemphigus foliaceus shows the characteristic intercellular fluorescence.

Ecthyma

Clinical Features: Ecthyma is sometimes considered a “deeper” variant of impetigo. It is produced by streptococci or staphylococci, and it presents as a shallow ulcer with a thick overlying scale-crust. The lower legs and feet are particularly common sites of involvement. Treatment is by cleansing and use of topical or systemic antimicrobial agents.13,14

Microscopic Findings: Biopsy confirms the presence of a shallow ulcer with overlying neutrophilic scale-crust (Fig. 17-3). Neutrophils are identified in the underlying dermal infiltrate. Bacteria can sometimes be identified with special staining.

Differential Diagnosis: These lesions closely resemble the excoriations with shallow ulcers that can be seen in a variety of pruritic conditions, including prurigo simplex.15

Necrotizing Fasciitis

Clinical Features: This is a “deep” form of cellulitis with necrosis. A penetrating injury to the skin often initiates the process. Affected individuals may be immunosuppressed to some degree. The process begins with erythema and edema, followed by blistering and necrosis and associated with systemic symptoms. The skin takes on a dusky, purpuric appearance. Mortality is significant, ranging from 20% to 34% in some series.16 A variety of organisms have been responsible, including both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, but group A streptococci are particularly linked to this disorder.17 Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome accompanies some of these cases. Surgical débridement and antimicrobial therapy are the mainstays of management.

Microscopic Findings: Changes include edema, neutrophilic infiltration, necrosis of epithelial structures (including hyaline necrosis of eccrine sweat glands), and connective tissue degeneration18 (Fig. 17-4A and B). Mixed septal and lobular panniculitis and fasciitis have been described.19 Thrombosis of vessels is seen at all levels of the dermis and subcutis and is associated with neutrophilic infiltration, thereby having the appearance of a septic vasculitis18,20 (Fig. 17-5). Clotting abnormalities may play a role in some cases, and in fact protein S deficiency has been reported on several occasions.21,22 A histopathologic classification scheme has been developed that focuses on the intensity of neutrophilic infiltration and the frequency of finding bacteria on Gram staining; stage 1 features neutrophilic infiltration and an absence of detectable bacteria, whereas stage 3 features few or no neutrophils in the face of positive Gram staining.23

Differential Diagnosis: The depth of involvement, as well as the degree of connective tissue degeneration and necrosis, are much greater in necrotizing fasciitis than in erysipelas or traditional forms of cellulitis. Pyoderma gangrenosum shows neutrophilic infiltration and necrosis, but thrombosis with changes of septic vasculitis are not seen in that disorder, except perhaps for “secondary vasculitis” seen in the immediate vicinity of the ulceration. Necrosis and connective tissue degeneration are also seen in forms of ischemia, including calciphylaxis and bullae related to coma or barbiturate intoxication, but these conditions lack the neutrophilic infiltration of necrotizing fasciitis, and Gram stains and tissue culture studies are typically negative.

Infectious Folliculitis

Clinical Features: Folliculitis due to bacterial infection is relatively common. It can be seen in otherwise healthy individuals, as a complication of atopic dermatitis, or as a manifestation of immunosuppressed states, such as acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

The furuncle, commonly known as a boil, presents as a tender, erythematous nodule that often forms a central pustule. Incision and drainage can be used to remove purulent and necrotic material.

The carbuncle consists of several adjacent follicles involved with the same type of process. S. aureus is the responsible organism in most cases. Treatments include warm compresses, incision and drainage when lesions become well demarcated and fluctuant, and appropriate antimicrobial agents.

Pseudomonas folliculitis is often contracted in contaminated swimming pools or hot tubs—hence the alternative term “hot tub folliculitis.” Papules, pustules, and nodules develop over the trunk and extremities, particularly in areas covered by a bathing suit. Patients are typically well in other respects. The causative organism is Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Cleaning of the contaminated facilities, with proper filtration and chlorination or bromination, should prevent outbreaks of this disorder. The lesions typically involute without treatment in 7 to 10 days, but antimicrobial therapy can also be used in selected circumstances. In one set of cases of Pseudomonas folliculitis occurring in immunosuppressed patients, the lesions evolved into ecthyma gangrenosum (see later discussion). The organism, P. aeruginosa serotype O-11, was found in the hospital water system where the infections occurred.24

Microscopic Findings: In furunculosis, a neutrophilic abscess forms around and within one or more hair follicles; this extends into the surrounding dermis and into the subcutis (Fig. 17-6). Follicular destruction ensues.25 An experimental study in mice inoculated with S. aureus has shown that these organisms attach to keratinocytes, where they proliferate around and then invade the hair follicle, extending in single-file fashion between the inner and outer root sheaths.26 In Pseudomonas folliculitis, there is an acute suppurative folliculitis with intraluminal abscess formation and associated perifolliculitis.27,28 Organisms are difficult to identify in tissue sections but can be readily cultured from the lesions.29

Differential Diagnosis: Bacterial folliculitis can resemble other forms of acute suppurative folliculitis, and differentiation requires knowledge of the clinical presentation as well as Gram staining and/or culture studies. Examples include acneiform folliculitis, fungal folliculitis (Majocchi granuloma), and the early neutrophilic folliculitis of pyoderma gangrenosum.

Toxic Shock Syndrome

Clinical Features: Two disorders have received this designation: staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Both are multisystem diseases. Staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome results from infection with strains of S. aureus that produce a particular toxin, termed toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1). Initial cases occurred in women using highly absorbent tampons; despite changes in tampon manufacturing, “menstrual” toxic shock syndrome still accounts for 50% of cases.30 Other sources of infection include surgical procedures, nasal packing, burns, and various cutaneous pyodermas. Features include fever, erythema, desquamation of palms and soles, hypotension, and involvement of multiple organ systems. Management includes the use of antibiotics, sometimes with corticosteroids or intravenous immunoglobulin. Streptococcal toxic shock syndrome accompanies disruption of the epidermal barrier with infection, is seen with destructive soft tissue infections such as necrotizing fasciitis, and is usually accompanied by bacteremia.31 The streptococci are usually M-types 1 and 3 with production of streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxins A to C (particularly A). Local pain, swelling, necrosis, or bulla formation is followed by fever, chills, myalgia, diarrhea, and central nervous system symptoms. Desquamation of palms and soles also occurs in some patients. Shock and multiorgan failure can ensue over a short period of time (48 to 72 hours). Both types of toxic shock syndrome are due to the superantigen properties of the exotoxins, resulting in profound T-cell activation and release of large quantities of cytokines.32 Treatment involves the use of antimicrobials that also inhibit bacterial toxins, along with intravenous immunoglobulin, surgical management of accompanying soft tissue infections, and supportive therapy.

Microscopic Findings: In staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome, there may be focal spongiosis with neutrophilic exocytosis, clusters of apoptotic keratinocytes, variable papillary dermal edema, and a perivascular and interstitial infiltrate that includes neutrophils, lymphocytes, and occasional eosinophils.33

In streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, the superficial changes may be similar to those of staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome, but there may be more extensive epidermal necrosis with subepidermal separation, hemorrhage, thrombosis,34 and suggestive vasculitic changes. Deeper thrombosis and inflammation are encountered when the findings are superimposed on necrotizing fasciitis.

Differential Diagnosis: Some of the superficial changes, such as edema and neutrophilic infiltration, are also seen in cellulitis and erysipelas. Significant epidermal necrosis or thrombosis, with or without vasculitic changes, suggests that the more severe toxic shock syndromes may be present, particularly streptococcal toxic shock syndrome, when associated with necrotizing fasciitis or disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Erysipelas and Cellulitis

Clinical Features: These are similar processes.35 In erysipelas, well-demarcated, warm, erythematous, indurated plaques are found in a variety of locations, but particularly the face and legs. It is caused by group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infection, although other streptococcal groups are responsible in different clinical circumstances. Various types of wounds may serve as the source of infection, with contributing factors that include chronic venous stasis and lymphedema.36,37 Cellulitis involves the deep dermis and subcutis and is most often due to group A streptococci or S. aureus, although Haemophilus influenzae has been a cause in children, and gram-negative aerobic and anaerobic bacteria can play a role in people with diabetes. Again, breaks in the skin, such as wounds or tinea pedis infection, may be responsible in many cases. Lesions consist of spreading erythema, sometimes with development of lymphangitic streaks and bullae. Fever and malaise may accompany the process. Both are treated with appropriate antimicrobial agents.38

Microscopic Findings: Erysipelas shows pronounced dermal edema, lymphatic dilatation, and a diffuse but often sparse infiltrate composed of neutrophils (Fig. 17-7). Perivascular accentuation of these cells is only slight. Although bacteria can be found within the involved tissues and sometimes in lymphatic spaces using Gram stain or other methods,39 in the author’s experience this is a rare event, and even tissue culture studies yield a high false negative rate. Immunofluorescent staining, if available, is a more sensitive method of detecting the causative organisms. The findings are similar in cellulitis, but the changes may be found deeper in the dermis or in the subcutis (Fig. 17-8).

Differential Diagnosis: Histopathologic evaluation is not always carried out in cases of erysipelas and cellulitis, and when it is used it generally provides only supportive rather than diagnostic information. The finding of neutrophils in the dermis, in the absence of an obvious source, such as ulceration, ruptured follicles or cysts, or leukocytoclastic vasculitis, should always raise the possibility of infection and prompt cultures or other laboratory studies. The neutrophilic infiltrate in Sweet syndrome is much heavier than in erysipelas or cellulitis, tends to be concentrated in the mid-dermis (although subcutaneous infiltration can definitely occur in that disease), and is associated with leukocytoclasis. Rheumatoid disease can be accompanied by cutaneous neutrophilic infiltrates, two examples being rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatosis and interstitial granulomatous dermatitis (the latter is not restricted to rheumatoid disease and can be seen in a wide variety of connective tissue, inflammatory, and infectious processes). The density of neutrophils in rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatosis and the presence of interstitial granulomas in interstitial granulomatous dermatitis would be distinctive. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis can be preceded or accompanied by deep dermal neutrophils that “splay” the collagen bundles, but there are characteristic degenerative and necrotizing changes in the subcutis that set that process apart.

Cutaneous Manifestations of Septicemia

Clinical Features: Characteristic cutaneous features are seen in several septicemic processes, largely due to the vasculopathy that accompanies these lesions.

Meningococcemia is due to infection with Neisseria meningitidis, a gram-negative diplococcus. In acute meningococcemia, there are fever, chills, hypotension and meningeal signs and symptoms, accompanied by an eruption of petechial to ecchymotic lesions. The latter are often angulated and display a “gun metal gray” necrotic appearance. This is a fulminant lethal disease if not treated promptly with antimicrobial therapy. Chronic meningococcemia is a more indolent although relapsing manifestation of the infection in which papular or nodular, purpuric skin lesions are accompanied by episodes of fever and arthralgias. Whereas acute meningococcemia is associated with endothelial injury and bacterial endotoxin–induced clotting (disseminated intravascular coagulation),40 chronic meningococcemia represents an immune complex vasculitis,41 most likely triggered by release of bacterial antigens. C7 deficiency has also been reported in association with chronic meningococcemia.42

Gonococcemia features fever, arthralgias, and a hemorrhagic pustular eruption. Typically, there are relatively few of these necrotizing pustules, and they are located on distal portions of extremities, particularly over large joints. This manifestation of gonococcal sepsis, sometimes termed the gonococcal dermatitis-arthritis syndrome, is uncommon, but tends to be seen in women with genital infections,43 following menses, or in those with deficiencies in late complement components. Endothelial damage with subsequent thrombosis is thought to be responsible, but circulating immune complexes can also be detected.44

Ecthyma gangrenosum is a manifestation of Pseudomonas sepsis. The lesions initially present as wheals, papules, and papulopustules that rapidly become hemorrhagic, violaceous, and necrotic. They quite often develop over the buttocks, inguinal region, or extremities. Patients with ecthyma gangrenosum are often significantly debilitated, with underlying conditions that include pancytopenia, leukemia, severe burns, or malignancy.

Subacute bacterial endocarditis, most often associated with infection by S. aureus, is associated with several classic peripheral signs that include Roth spots (retinal hemorrhages with white or pale centers), subungual hemorrhages, Osler nodes, and Janeway lesions. Osler nodes are tender erythematous papules that occur on ventral surfaces of the fingertips and toes, whereas Janeway lesions are similar-appearing but nontender macules, papules, or nodules that develop on the palms and soles. The current view is that, in subacute bacterial endocarditis, these two lesions are manifestations of immune complex vasculitis—most likely a response to bacterial antigens—rather than embolic phenomena arising from endocardial vegetations.45 However, in acute bacterial endocarditis, there is evidence that septic emboli are responsible.46,47

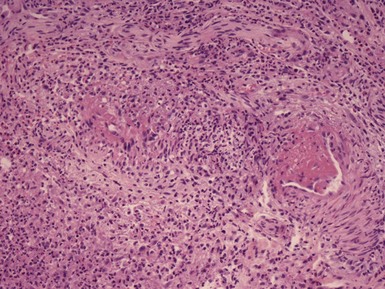

Microscopic Findings: In acute meningococcemia, there is severe vessel injury, consisting of thrombosis, necrosis of endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells and pericytes, and relatively sparse infiltrates of neutrophils with minimal leukocytoclasis. Numerous meningococci can be observed within endothelial cells and neutrophils. Immunoglobulins and complement can be identified in vessel walls.48 In chronic meningococcemia, the changes are those of leukocytoclastic vasculitis49 (Fig. 17-9). Organisms cannot be demonstrated with the usual histopathologic methods, including direct immunofluorescence.50 However, N. meningitides–specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technology applied to skin biopsy specimens has recently been used successfully to diagnose chronic meningococcemia.51

Figure 17-9 Chronic meningococcemia. The findings are those of leukocytoclastic vasculitis involving a medium-sized, deep dermal vessel.

In gonococcemia, findings are similar to those in meningococcal septicemia and include a combination of vasculitis and thrombosis (Fig. 17-10). Superficial and deep dermal vessels are involved, including arterioles, and the infiltrating cells include lymphocytes as well as neutrophils. Erythrocyte extravasation is also prominent. Gonococci are uncommonly identified in blood vessel walls with routine methods (i.e., Gram staining),52 but they can be found within the contents of pustular lesions and can also be detected using direct immunofluorescence. The likelihood of finding organisms in tissue sections may depend on the degree of bacteremia and the age of the sampled lesion.52 Culture studies from skin lesions are frequently negative, probably indicating that organisms present in these lesions are frequently nonviable. However, cultures from cervix, blood, or other sites can be used to confirm the diagnosis.

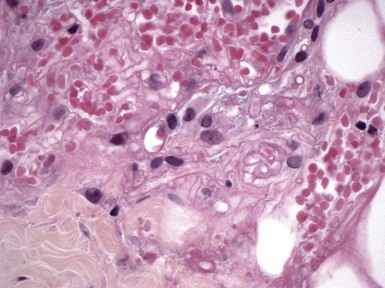

In ecthyma gangrenosum, necrotizing changes of dermal vessels are present, often with limited or no appreciable inflammation.53,54 Numerous Pseudomonas organisms can be identified in the walls of vessels, generally sparing the lumen and intima (Fig. 17-11). Necrosis of epidermis and adnexal structures and degenerative changes in connective tissues are frequently observed.55 The changes in Osler nodes and Janeway lesions in bacterial endocarditis may vary, depending on whether the condition is acute or subacute.

Figure 17-11 Ecthyma gangrenosum. Numerous bacillary organisms, representing Pseudomonas, surround thrombosed vessels with necrotizing changes.

Lesions of subacute bacterial endocarditis show leukocytoclastic vasculitis56 (Fig. 17-12), while those of acute bacterial endocarditis are more apt to show emboli and dermal microabscess formation.46

Differential Diagnosis: The changes of “septic vasculitis” (vascular injury with both inflammation and fibrosis) are features of acute meningococcemia, gonococcemia, ecthyma gangrenosum (although inflammation is often slight in the latter), and acute bacterial endocarditis. Similar findings could be seen in septicemia due to other microorganisms, and therefore special stains and culture studies are warranted as part of the workup of these cases, with the realization that both may be negative when performed on the skin lesions. For that reason, cultures of blood or other tissues or special methods such as PCR may be necessary. Vasculitis with thrombosis can also be seen in noninfectious disorders—particularly, in the author’s experience, cryoglobulinemia. The infiltrate-poor vascular changes in ecthyma gangrenosum can also be seen in Vibrio vulnificus septicemia. This infection can develop following consumption of raw seafood or through wounds contracted along coastal waters. Indurated plaques and bullae show cutaneous necrosis and connective tissue degeneration, with myriads of organisms (which, like Pseudomonas, are gram-negative bacilli) in the walls of vessels. The changes in chronic meningococcemia and subacute bacterial endocarditis resemble those of leukocytoclastic vasculitis due to other causes, and therefore other clinical and laboratory data are necessary to establish the correct diagnosis in such cases.

Botryomycosis

Clinical Features: Botryomycosis is an uncommon form of bacterial infection characterized microscopically by the presence of granules that resemble those of actinomycosis and mycetoma (see subsequent discussions). The lesions consist of nodules that can become crusted or drain purulent material containing granules similar to the sulfur granules of actinomycosis. Patients with botryomycosis lesions are often immunosuppressed, demonstrating deficient cell-mediated immunity in the face of a normal or hyperactive humoral immune system. Association with AIDS has been reported.57 A wide variety of gram-positive and gram-negative organisms can produce these lesions, with S. aureus being a frequent agent. Experimental reproduction of these lesions has been difficult to accomplish.58,59 Cultures of lesions are frequently negative, and even mouse inoculation may fail to demonstrate evidence for infection. Furthermore, the lesions may be resistant to systemic antimicrobial therapy. These findings may be related to the relatively “protected” environment created by the peculiar host interaction with the organism.

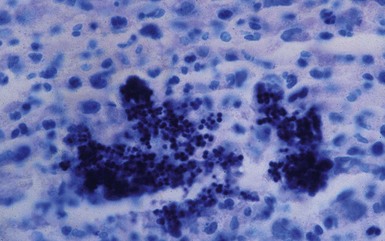

Microscopic Findings: Skin biopsies show varying degrees of hyperkeratosis and acanthosis. There is a perivascular infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells within the superficial and deep dermis. Dermal neutrophilic abscesses contain granules that consist of an eosinophilic matrix (Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon) and central collections of organisms (Fig. 17-13). In the case of S. aureus, these are composed of basophilic, gram-positive cocci, arranged in pairs and tetrads, which stain particularly well with the Giemsa method (Fig. 17-14). IgG and C3 deposition within the granules has been found with both immunofluorescent and immunohistochemical methods57,60 and reflects a host immune response to bacterial antigens.

Differential Diagnosis: The grains of botryomycosis must be distinguished from those associated with other classes of organisms, including higher bacteria, such as actinomycetes and Nocardia, and true fungi. The morphology of these organisms is quite different from the agents of botryomycosis and can be evaluated through the use of periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) and Grocott methenamine silver (GMS) as well as Gram stains (for further information, see “Nocardiosis,” “Actinomycosis,” and “Mycetoma”).

Malakoplakia

Clinical Features: Malakoplakia (alternative spelling, malacoplakia) was first described in 1902, when Michaelis and Gutmann described three examples of a tumor of the urinary bladder with unique intracellular inclusion bodies.61,62 In 1903, von Hansemann described aggregates of short bacilli attached to similar-appearing cells. It was later learned that these cells, now called von Hansemann cells, are macrophages. He named the disorder “malacoplakia vesicae urinariae” (soft plaque of the urinary bladder).61,63 Although the genitourinary tract is involved most often, the process has been identified in skin, either through extension from an underlying focus of disease or as a primary cutaneous lesion.64,65 A number of the cutaneous cases have occurred in the perianal region.63 Lesions have presented as ulcers, indurated areas with draining sinuses, fluctuant masses, or perianal polyps.61 Escherichia coli is implicated in the majority of cases, but other organisms have been described, including Rhodococcus equi in patients with AIDS.66 The occurrence of malakoplakia has been linked to immunosuppression, associated with sarcoidosis or corticosteroid therapy in some cases.61 The pathogenesis of the disease may be related to macrophages with defective bactericidal capability. Although the mechanism is unclear, one study indicated decreased cyclic guanosine monophosphate in monocytes, associated with defective release of lysosomal β-glucuronidase.67 Treatment includes antimicrobial therapy, excision for localized lesions, and treatment of possible underlying immunosuppressive disorders.

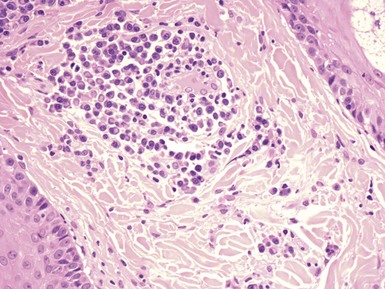

Microscopic Findings: There are sheets of large macrophages with granular cytoplasm (von Hansemann cells) within the dermis and subcutis (Fig. 17-15). The key microscopic features are the Michaelis-Gutmann bodies, found within macrophages. These targetoid inclusion bodies, somewhat difficult to identify with H&E stain, are thought to represent accumulations of nonexocytosed phagolysosomes that have calcified. They possess a dense calcium hydroxyapatite core and variable amounts of iron. Therefore, they are best demonstrated with PAS, von Kossa, Perls, and Giemsa methods68 (Fig. 17-16A and B). Bacteria, usually gram-negative bacilli (E. coli), can sometimes be identified within macrophages.69 Polyclonal anti–bacille Calmette Guérin (anti–Mycobacterium bovis) has also been used successfully to identify organisms and is particularly useful when only a few microorganisms are present in tissue sections.70

Differential Diagnosis: Macrophages with granular cytoplasm could bear some resemblance to the cells of granular cell tumor. The cells of granular cell tumor are polyhedral, have small central hyperchromatic nuclei, and occasionally contain large granules termed pustule-ovoid bodies of Milian. The classic examples of this tumor are thought to be composed of modified Schwann cells and are S-100 positive, a result not seen in malakoplakia. Granular cell changes in other tumors (e.g., dermatofibroma, basal cell carcinoma) have other configurational features more in keeping with ordinary examples of those tumors, as well as characteristic immunohistochemical findings. The rare examples of the primitive nonneural granular cell tumor are negative for S-100 but stain for other markers such as NKI/C3 and PGP9.5.71 At low magnification, the granularity of von Hansemann cells can suggest xanthoma, but close inspection of cell detail shows that the cytoplasm of these cells is granular rather than finely vacuolated. Sometimes, changes in healing wounds include accumulations of macrophages with granular cytoplasm. However, in none of these potentially confounding lesions are there structures with the morphologic and staining characteristics of Michaelis-Gutmann bodies.

Corynebacterial Infections

Clinical Features: Two particular cutaneous infections caused by corynebacteria are erythrasma and pitted keratolysis. Another cutaneous infection, trichomycosis axillaris/pubis, is caused by Corynebacterium tenuis and occasionally other Corynebacterium species. It is characterized by yellowish, red, or black nodular deposits along hairs and is diagnosed by gross or microscopic inspection of the hair shafts; the latter shows numerous bacteria embedded in the material encasing the involved hairs.

Erythrasma consists of well-demarcated, brownish red, scaly patches in intertriginous locations, especially the groin, toe webs, axillae, and inframammary areas. Itching, or a burning sensation, is common in the groin area. The causative organism is Corynebacterium minutissimum, a small gram-positive bacillus. The lesions show a distinctive coral red fluorescence with Wood light, which emits light mainly at a wavelength of 360 nm; the fluorescence is due to a porphyrin produced by the organism. This porphyrin production has actually been exploited in a treatment option using photodynamic therapy.72 Most often, however, topical or systemic antimicrobial agents are used in management, including erythromycin. Pitted keratolysis causes the formation of shallow, rounded pits in stratum corneum, especially in the soles of the feet. This is particularly prone to occur in hot, humid conditions when there is increased sweating. The author has also found this infection in a transgrediens variant of palmar hyperkeratosis. The cause is the keratolytic action of certain bacteria, including Corynebacterium species; however, other organisms can be responsible for this condition, including the gram-positive coccoid organism Kytococcus (formerly Micrococcus) sedentarius and Dermatophilus congolensis, a gram-positive facultative anaerobe that produces thin filaments and coccoid forms. Coalescent pits can form linear depressions or shallow “fissures.” Topical erythromycin and clindamycin have been used successfully to treat these lesions.73

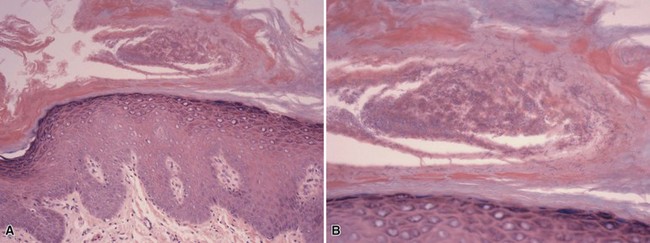

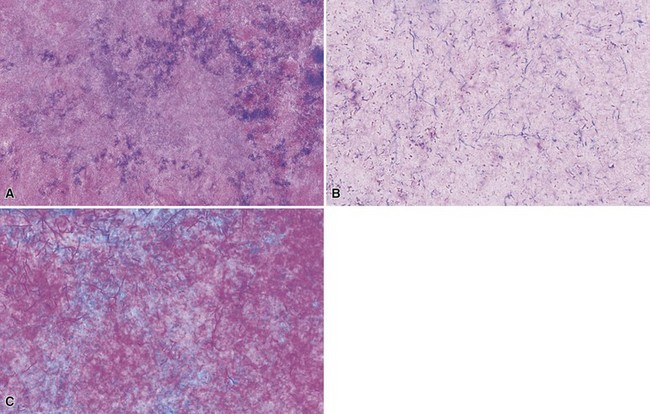

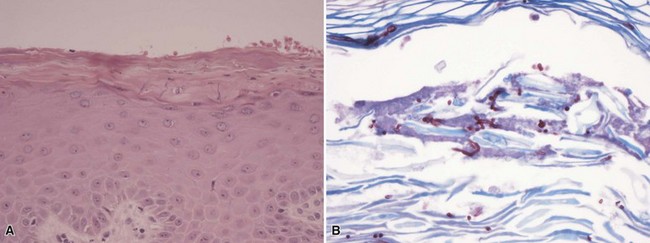

Microscopic Findings: In erythrasma, the biopsy findings are often minimal, sometimes consisting of only slight spongiosis. The organisms, small coccobacilli, can be found in the stratum corneum but most often require special staining for confirmation74,75 (Fig. 17-17A and B). Those that can be used effectively include Gram, PAS, or GMS stains.76 Pitted keratolysis shows irregularities of the surface stratum corneum with formation of pits that extend to various depths. Within the base of the pits are coccoid to filamentous organisms that again can be recognized with Gram (gram-positive), PAS, or GMS methods73,77,78 (Fig. 17-18A and B).

Differential Diagnosis: The microscopic changes of erythrasma and pitted keratolysis can be quite subtle (this is particularly the case in erythrasma), and as a result these conditions qualify as “invisible dermatoses.”79 In the absence of a supportive clinical history, a high index of suspicion needs to be maintained, and part of the evaluation of a biopsy with minimal findings includes the performance of special stains for organisms (Gram, PAS, or GMS). Once the organisms have been found, they must be distinguished from Pityrosporum organisms, dermatophytes, or Candida species. However, the hyphae, pseudohyphae, or spores in those conditions tend to be much larger than the small coccobacillary forms and filaments of corynebacteria, despite overlapping results with special stains.

Anthrax

Clinical Features: Anthrax has gained notoriety among professionals and the public due to its potential use in terrorist attacks. In the United States, the usual source of infection is the handling of infected animal hides or wool (“wool sorters disease”). Aerosolized spores of the infectious agent, Bacillus anthracis, sent through the mails in the form of a powder, were used as a form of bioterrorism in 2001.80,81 Inhalation results in a necrotizing mediastinal infection, with consequent bacteremia and hemorrhagic meningitis. Similarly, ingestion of spores causes intestinal ulceration with hemorrhage. Most cases in the United States consist of cutaneous lesions, which begin as papules that enlarge and evolve into hemorrhagic pustules, followed by formation of a black eschar surrounded by erythema. Surprisingly, pain is minimal. Prompt antimicrobial treatment is essential.

Microscopic Findings: Fully developed lesions are necrotic, with an ulcerated surface. The adjacent epidermis shows spongiosis with acantholysis and microvesicle formation. The dermis is markedly edematous. Vasodilatation and erythrocyte extravasation are pronounced. The intensity of inflammation is variable, but the infiltrate consists mainly of neutrophils, which are found within both the dermis (sometimes with abscess formation) and viable portions of the epidermis.82 A mixture with other inflammatory cell types, including lymphocytes and macrophages, is also described.83 There may be thrombosis and/or fibrin deposition around vessel walls.83 The numbers of organisms vary from case to case. They can occasionally be identified in routinely stained sections but often require special staining. With Gram staining, they appear as relatively large gram-positive bacilli measuring approximately 1 × 9 microns. Other methods that are more sensitive include silver stains (the Steiner and Steiner method) and immunohistochemical staining using antibody to B. anthracis antigen.82

Differential Diagnosis: The combination of necrosis, ulceration, and pronounced dermal edema with neutrophils certainly suggests other types of infectious disease, such as necrotizing fasciitis, although in the latter example the clinical findings are quite different. Other noninfectious dermatoses may be considered, particularly those that feature combinations of dermal edema and neutrophilic infiltration, such as pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet syndrome. Pronounced dermal edema occurs in virally induced, orf, or milker nodules. In those infections, there are marked elongation of the rete ridges and vacuolated keratinocytes with intranuclear eosinophilic inclusion bodies. However, in the acute weeping stage of those lesions, the epidermis is necrotic and inclusions are not identifiable, so that there may be greater overlap with the findings in anthrax. The key to the diagnosis of anthrax is a high index of suspicion and the obtaining of a Gram stain, which has a high likelihood of showing the characteristic organisms. The infection can be confirmed by culture studies. There are several potential caveats. First, with age these organisms can show variable staining or become gram-negative. Second, if laboratories are not alerted to the possibility of anthrax, it is possible that cultures indicating the presence of Bacillus species may not be further analyzed due to the likelihood of a common contaminant organism, Bacillus cereus.80

Chancroid

Clinical Features: Chancroid is a sexually transmitted disease caused by Haemophilus ducreyi, a gram-negative coccobacillus. Regional outbreaks of the disease are reported from time to time (e.g., in Orange County, California,84 and in the New Orleans area),85 and it is encountered in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive individuals.86 Lesions begin in the genitalia as macules or pustules and evolve to form tender ulcers with minimal induration. Autoinoculation results in the formation of “kissing lesions.” Suppurative lymphadenitis occurs in some cases. Diagnosis is made by a combination of clinical features, smears, and cultures. However, coexistence with other sexually transmitted diseases, including syphilis, is definitely possible,87 and other evaluations, including serologic testing, should be part of the workup in cases of possible chancroid infection. Treatment includes antimicrobial therapy, including macrolide antibiotics or ciprofloxacin.

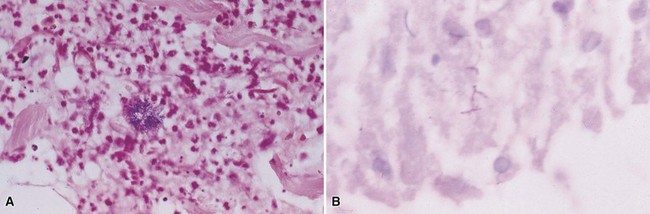

Microscopic Findings: The microscopic features of chancroid are fairly characteristic, if not pathognomonic, but require a well-oriented biopsy of sufficient depth to assess superficial and deep dermal changes. There is a “triple zone” arrangement beneath the ulcer, each horizontally oriented zone showing different microscopic changes. At the ulcer base, there is a zone of fibrin deposition with intermingled necrotic tissue, neutrophils, and erythrocytes. Beneath this is a zone composed of proliferative vessels, some with endothelial proliferation, degenerative change, and thrombus formation. Deep to this focus is a zone composed mainly of lymphocytes and plasma cells.88 Although this zonation can indeed be observed, it is not always as neatly laid out as implied by the description (Fig. 17-19A and B). Organisms are difficult to identify in tissue sections, even when stained with Gram or Giemsa methods. Smears from the undermined ulcer edge are more likely to show the organisms, which have a tendency to line up in a “school of fish” arrangement. Cultures require the use of special procedures and media, as have been detailed in a recent study.89

Differential Diagnosis: Despite the zonation observed in examples of chancroid, this arrangement may not be clearly observable in all cases. This may be due in part to biopsy technique; however, ulcerated lesions due to a number of different causes tend to show fibrin, proliferative vessels, and admixed acute and chronic inflammation. This makes specific diagnosis difficult, particularly when organisms are so difficult to identify in tissue sections. Two sexually transmitted diseases that bear a clinical resemblance to (and may even coexist with) chancroid are herpesvirus infection and syphilis. Therefore, histopathologic evaluation may also require careful search for viropathic changes or immunohistochemical evaluation for herpes simplex or treponemal antigens. Ulcerative diseases that are noninfectious, such as aphthosis or Behçet disease, also show similar morphologic features in biopsy specimens.

Granuloma Inguinale

Clinical Features: Granuloma inguinale, also known as donovanosis, is a sexually transmitted disease produced by the intracellular gram-negative bacillus Klebsiella granulomatis. This organism had been previously designated Calymmatobacterium granulomatis, but gene sequencing has shown a high level of identity with species of Klebsiella that are human pathogens.90 After a variable incubation period, a papule or nodule appears and subsequently ulcerates, forming a highly vascular, expanding lesion with a distinctly “beefy” appearance. “Pseudobuboes” represent inguinal swellings associated with the ulcers; they have received this name because they do not represent lymphadenopathy but subcutaneous granulation tissue that may subsequently break down and ulcerate. Lesions may be particularly extensive, but the level of pain associated with them tends to be disproportionately low. Diagnosis often depends on smears obtained from tissue scrapings or as touch preparations of skin biopsies; culture methods are being worked out but are not routinely available. The infectious agent has been detected using a procedure termed genital ulcer disease multiplex PCR, with amplification products detected by an enzyme-linked amplicon hybridization assay.91

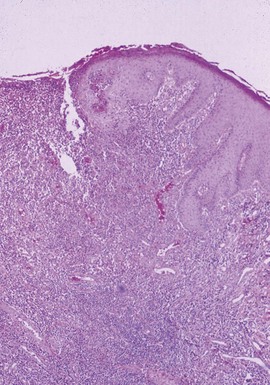

Microscopic Findings: In fully developed lesions, there is an ulcer surrounded by marked acanthosis, which may achieve pseudoepitheliomatous proportions (Fig. 17-20). Exuberant granulation tissue is present near the ulcerated surface. The underlying dermis shows a dense, mixed infiltrate composed of macrophages, plasma cells, a few lymphocytes, and scattered neutrophils that sometimes form microabscesses (Fig. 17-21). The organisms, known as Donovan bodies, are found within macrophages but are easier to find in smears and tissue imprints. They are approximately 1 to 2 mm in diameter and best seen with Giemsa stain, showing bipolar staining with a resemblance to a “closed safety pin.”92,93 Wright-Giemsa is an effective staining method when examining smears. On semithin sections obtained from Epon-embedded specimens, the organisms appear to be surrounded by a vacuolated structure that represents a phagolysosome.94 However, ultrastructural study has also shown a layer of homogeneous material surrounding the organisms, suggesting that there may be a surrounding capsule.95

Differential Diagnosis: The tissue morphology of the granulomatous lesions, in the appropriate clinical context, is suggestive of granuloma inguinale but not entirely diagnostic, because many of the changes can be seen in ulcerative diseases due to a number of causes. Therefore, diagnosis depends on finding the organisms. Their intracellular location raises consideration of the other major “parasitized histiocyte” diseases: rhinoscleroma, histoplasmosis, and leishmaniasis. The ability to distinguish among them obviously is greatly enhanced by knowledge of the clinical presentation. However, the organisms of granuloma inguinale are slightly smaller (about 1 to 2 µm) than those in the other three conditions, whose organisms are all in the range of 2 to 4 µm. The organisms of rhinoscleroma (also representing a species of Klebsiella) lack a surrounding capsule-like space. Histoplasma organisms are surrounded by a clear space that does not represent a true capsule, and they stain well with the traditional methods for fungi, PAS, and GMS. Leishmania are nonencapsulated organisms that feature both a nucleus and a kinetoplast, best demonstrated with a Giemsa stain. Toxoplasma organisms can sometimes be found in macrophages but may be organized as pseudocysts and are also present in keratinocytes of epidermis and sweat ducts and within arrector pili muscle.96 The organisms are weakly positive for PAS but are negative for the GMS stain.96 They can also be stained with antibodies specific for Toxoplasma.

Rhinoscleroma

Clinical Features: Rhinoscleroma is a chronic inflammatory disease of upper respiratory structures caused by a gram-negative bacillus, Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis. This condition is encountered in Central and South America and parts of Asia, and it is occasionally reported in the United States. Rhinoscleroma particularly affects the nasal vestibule, but other parts of the nose and pharynx can also be involved. Nasal discharge is followed by nodular and sclerosing lesions that sometimes ulcerate. Nasal obstruction and mutilating changes of the central portions of the face ensue. Treatment is often prolonged and includes fluoroquinolones and other agents as well as surgical intervention when necessary.97,98

Microscopic Findings: The lesions are composed of numerous plasma cells, many of which form Russell bodies and vacuolated macrophages termed Mikulicz cells.98,99 Russell bodies are eosinophilic, somewhat refractile structures that are either anucleate or show a pyknotic, compressed nucleus at one edge. The appearance of these bodies is due to accumulation of immunoglobulin within plasma cell cytoplasm. Mikulicz cells, some of which are quite large (>100 µm in diameter), contain the Klebsiella organisms; these stain with Gram, PAS, or silver stains such as the Warthin-Starry stain. They can be seen in tissue sections, where they are somewhat easier to identify than the organisms of granuloma inguinale, but as in the latter infection, they can also be demonstrated in tissue smears or imprints.100

Differential Diagnosis: Differentiation from other infectious diseases with “parasitized histiocytes” is discussed earlier (see “Granuloma Inguinale”), with particular reference to the morphology of these microorganisms in tissues. In rhinoscleroma, the vacuolated Mikulicz cells are particularly distinctive, much more so than is the case in granuloma inguinale, which in turn is said to have dermal neutrophilic microabscesses as one of its distinctive features. Pseudo-Mikulicz cells have recently been reported adjacent to a superficially invasive squamous cell carcinoma; no organisms were found in this case, and progressive disease was not documented.101 Plasma cells can be encountered in any of these disorders, and in addition can be numerous in other situations; examples include secondary syphilis (where they are arranged around vessels in a “coat-sleeved” configuration), plasmacytoma, and as a host response to malignant epithelial tumors such as basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Russell bodies are occasionally prominent in plasma cell infiltrates due to a variety of causes, but among the “parasitized histiocyte” diseases, they are most characteristic of rhinoscleroma. In the author’s experience, they are usually difficult to identify in neoplastic plasmacellular proliferations such as plasmacytoma or cutaneous involvement in multiple myeloma.

Cat Scratch Disease and Bacillary Angiomatosis

Clinical Features: Cat scratch disease in most cases is caused by Bartonella (Rochalimaea) henselae, an aerobic, gram-negative bacillus. Within 2 to 5 days following a scratch or bite from an infected cat, a skin lesion may develop, consisting of one or more papules resembling insect bites. Within several weeks of the primary skin lesion, tender, swollen lymph nodes develop in the drainage site. Fever, headache, backache, or abdominal pain may develop. Suppuration develops at the site of the involved lymph nodes in up to 50% of cases. A widespread exanthem and erythema nodosum are additional cutaneous findings that are observed in some cases. When the conjunctiva is the primary site of the lesion, granulomas can develop at the site associated with preauricular adenopathy; this is known as Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome. The adenopathy resolves over several months. Systemic complications include acute encephalopathy and splenomegaly, and involvement of liver and lung has been reported. Material obtained by skin biopsy or swab techniques can be cultured in human embryonic lung fibroblasts, but more rapid detection of the organism can be obtained by real-time reverse transcriptase–PCR using the same biopsy material.102

In bacillary angiomatosis, lesions develop that closely resemble pyogenic granulomas, although subcutaneous nodules or ulcers also occur. This condition most often develops in the setting of immunosuppression, particularly in AIDS, where the cause is also B. henselae, the same organism associated with cat scratch disease. The same types of lesions are encountered in homeless individuals who do not have AIDS; in these instances the causative organism is Bartonella quintana. Similar lesions also occur in individuals who live in the valleys of Peru and neighboring countries. Called verruga peruana, the lesions represent a stage of Oroya fever, or Carrion disease, and are caused by Bartonella bacilliformis. Systemic involvement can occur in bacillary angiomatosis, with lesions in the bones, liver, and spleen. Erythromycin, doxycycline, and other antimicrobial agents are effective in this disease.103–106

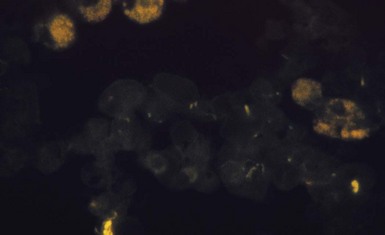

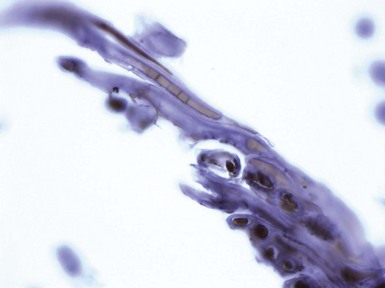

Microscopic Findings: In cutaneous lesions of cat scratch disease, the epidermis shows varying degrees of parakeratosis, edema, and exocytosis; an ulcer sometimes occurs. Within the dermis there are foci of necrobiosis, sometimes containing lymphocytes, surrounded by palisaded macrophages. Lymphocytes surround the palisaded macrophages, and eosinophils can also be identified. Additional findings include fragmented nuclei and perivascular infiltrates composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells107 (Fig. 17-22A). Bacillary organisms can be found in tissue sections, staining best with silver methods such as the Warthin-Starry stain (see Fig. 17-22B), but they can also be found with tissue Gram stains (Brown and Brenn).108 The organism, B. henselae, can also be detected by PCR methodology, and it can be found in archival tissues.109 Lymph node biopsies show similar but often better developed findings, including the characteristic “stellate” abscess, consisting of a central zone of necrosis containing numerous neutrophils, surrounded by palisades of macrophages, which in turn are surrounded by a zone of lymphocytes.107

Figure 17-22 Cat-scratch disease. A, This lesion was tangentially sectioned, accounting for the appearance of the epidermis. Within cross-sectional profiles of dermis, there are lymphocytes, macrophages, and plasma cells with some nuclear fragmentation and erythrocyte extravasation. B, Bacillary organisms can be identified with the Warthin-Starry stain.

In bacillary angiomatosis, there are dermal collections of blood vessels with plump endothelial cells that sometimes display significant cytologic atypia110 (Fig. 17-23). Occasional ulceration and a surrounding epidermal collarette contribute to an image resembling pyogenic granuloma. Neutrophils, with leukocytoclasis, are also identified (Fig. 17-24). The organisms appear as gray, granular material on H&E-stained sections. As in cat scratch disease, they are best demonstrated with silver stains, particularly Warthin-Starry and GMS (Fig. 17-25), but they can also be identified with Giemsa, PAS, or Alcian blue methods.110,111 Direct immunofluorescence or PCR can also be used to confirm the presence of organisms in tissues.

Figure 17-23 Bacillary angiomatosis. Low-power view shows an exuberant proliferation of vessels with accompanying inflammatory cells and erythrocyte extravasation.

Differential Diagnosis: The skin lesions are characteristic but not pathognomonic for cat scratch disease, and the changes could be mimicked by other conditions that feature palisaded necrobiotic granulomas, including tuberculosis, granuloma annulare, lupus miliaris, and the short-lived primary cutaneous lesions of lymphogranuloma venereum. The “stellate abscess” found in lymph nodes is also typical for this disease but can be found in a number of other conditions, including tularemia, lymphogranuloma venereum, and sporotrichosis. The author has also seen similar abscesses within lymph nodes draining the site of vaccination therapy for the treatment of melanoma. Therefore, detection of the organism using silver stains or PCR methods is key to making a specific diagnosis.

Regarding bacillary angiomatosis, these lesions should be distinguished from pyogenic granuloma, which shares a number of the low-power features, including (sometimes) ulceration, an epidermal collarette, and proliferative vessels in a variably edematous stroma. However, the endothelial cells in bacillary angiomatosis are larger and demonstrate greater atypia than seen in pyogenic granuloma. Neutrophils represent a significant finding in bacillary angiomatosis and are found in lesions even in the absence of ulceration. Furthermore, in contrast to bacillary angiomatosis, pyogenic granuloma represents a form of lobular capillary hemangioma, and, although grouping of vessels in lobulated fashion is not always obvious, most examples of pyogenic granuloma show this feature. The key to diagnosis is the detection of bacillary organisms, which as mentioned present as aggregates of gray material surrounded by neutrophils on H&E sections and can be more clearly demonstrated with silver methods. Kaposi sarcoma might also be considered in the differential diagnosis of lesions of bacillary angiomatosis, but irregular vascular channels, spindled cells, and hyaline globules are not found in bacillary angiomatosis,110 and staining for human herpesvirus-8 is also negative in this condition.112 Regarding endothelial markers, the cells in bacillary angiomatosis are regularly positive for factor VIII–related antigen and Ulex europaeus lectin110; in Kaposi sarcoma, the cells of well-formed vessels stain positively for factor VIII–related antigen and with Ulex europaeus, but the spindle cell component does not reliably stain for these markers.113

Mycobacterial Infections

Clinical Features: Cutaneous tuberculosis has become uncommon in the United States but is still seen in travelers, immigrants, and immunosuppressed individuals. Among those forms of the disease that are uncommonly encountered here are primary cutaneous tuberculosis, miliary tuberculosis, and tuberculosis cutis orificialis. Primary cutaneous tuberculosis arises from direct inoculation of the skin in an individual who has not been previously infected by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It manifests as an ulcerated lesion that is followed by enlarged, tender regional lymph nodes—a similar scenario to the Ghon complex that develops in the lungs. Miliary tuberculosis consists of widespread papules and pustules on the skin due to hematogenous dissemination, usually in the setting of advanced disease. In tuberculosis cutis orificialis, shallow ulcers develop in mucocutaneous surfaces, again the result of advanced disease.

Other manifestations of the disease that are occasionally seen include lupus vulgaris, tuberculosis verrucosa cutis, and scrofuloderma. Lupus vulgaris is a form of secondary or reactivated tuberculosis that develops in previously infected individuals. It presents typically in the head and neck region as reddish brown papules or nodules. When examined using diascopy (pressing the lesions with a glass slide), the lesions have a distinctive “apple-jelly” appearance. Ulcerations and scars develop, and new lesions can develop in older, atrophic areas. Considerable facial deformity can occur. Squamous cell carcinoma can develop in old lesions. Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis arises from inoculation of the skin of an individual who has been previously infected and has substantial immunity to the organism. A classic example of this phenomenon is the “prosector’s wart” due to inoculation during performance of an autopsy. These verrucous papules and plaques most commonly arise in acral sites that are readily subjected to trauma. They may heal with scarring. In scrofuloderma, subcutaneous nodules form as the result of cutaneous infection from an underlying focus of disease, typically from cervical lymph nodes but also from other structures or via surgical procedures. These nodules suppurate and form draining sinuses, healing with linear, cordlike scars.

Tuberculids are cutaneous lesions that develop secondary to a distant focus of disease. They tend to reflect strong host immunity and have been considered autosensitization phenomena as is the case in “ids” of other types. Although mycobacteria traditionally cannot be identified in these lesions, M. tuberculosis DNA has been found in some of these lesions using PCR methods. Three lesions have been confirmed in their association with tuberculosis: erythema induratum (see Chapter 7),114 papulonecrotic tuberculid,115 and lichen scrofulosorum. The latter has not to date shown demonstrable mycobacterial DNA in skin lesions by PCR methods, although mycobacterial DNA has been found in lichen scrofulosorum lesions associated with Mycobacterium szulgai infection (an atypical mycobacterium in group II of the Runyon classification). Regarding the clinical appearance of these lesions, erythema induratum presents as subcutaneous nodules, sometimes ulcerated, particularly on the calves of the lower legs; papulonecrotic tuberculid as bilaterally symmetrical crops of necrotic to pustular lesions on the face and extremities; and lichen scrofulosorum as tiny discrete follicular papules on the trunk.

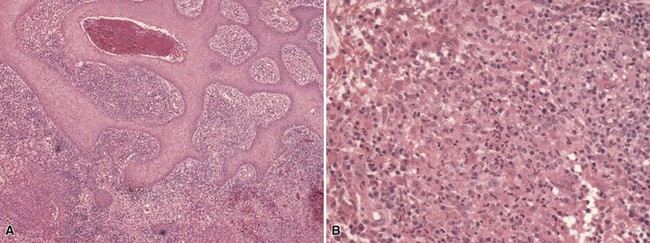

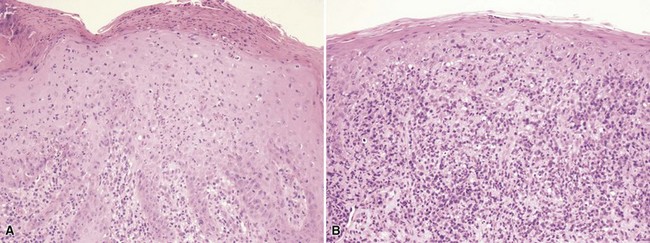

Microscopic Findings: Lupus vulgaris shows tuberculoid granulomas that are often concentrated in the upper dermis, particularly around follicular units, although they can also extend into the subcutis (Fig. 17-26A). Tuberculoid granulomas contain epithelioid macrophages, including multinucleated giant cells (some of the Langhans type with horseshoe arrangements of nuclei), surrounded by lymphocytes and plasma cells. Caseation is frequently absent, but when observed tends to be slight (see Fig. 17-26B). Zones of fibrosis are identified in long-standing lesions. Organisms are difficult to identify, even with traditional special stains such as the Ziehl-Neelsen method. Better results may be obtained by specific immunohistochemical staining or, particularly, with PCR methods.116 Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis shows hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and acanthosis (Fig. 17-27A). The inflammatory infiltrate can vary, from a mixture of neutrophils (including intraepidermal or dermal abscess formation), lymphocytes, and granulomatous elements to a more tuberculoid granulomatous infiltrate, uncommonly with caseous necrosis117,118 (see Fig. 17-27B). Although organisms are said to be more numerous in these lesions, they are usually difficult to identify with special stains, and even culture results are frequently negative. Scrofuloderma features a zone of caseous necrosis, surrounded by epithelioid macrophages, multinucleated giant cells of Langhans type, and plasma cells (Fig. 17-28). Organisms are present in sufficient numbers to be readily identified with special stains.119

Figure 17-26 Lupus vulgaris. A, This manifestation of secondary (reactivated) tuberculosis shows granulomas concentrated in the upper dermis. B, The granulomas are composed of epithelioid macrophages, surrounded by lymphocytes and plasma cells. Caseation is frequently absent.

Figure 17-27 Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis. A, Findings include marked acanthosis (probably exaggerated here by tangential sectioning). B, The dermal infiltrate includes a mixture of neutrophils and epithelioid macrophages. Caseous necrosis was not identified in this lesion.

Figure 17-28 Scrofuloderma. Zones of caseous necrosis are surrounded by granulomatous elements, lymphocytes, and plasma cells.

Regarding the histopathology of tuberculids, the findings in erythema induratum are discussed in Chapter 7. Papulonecrotic tuberculid features vasculitis with thrombosis, wedge-shaped degenerative changes of the dermis or follicular necrosis, and poorly organized granulomatous inflammation.120–122 Organisms are not identified with routine methods but have been found with PCR technology. Lichen scrofulosorum lesions show noncaseating granulomas, typically surrounding hair follicles or sweat ducts; organisms are not identified.123

Differential Diagnosis: The rarity of tuberculosis in the United States (with the possible exception of immunosuppressed populations) increases the risk that tuberculosis may not be considered when evaluating granulomatous dermal infiltrates. It most often becomes a consideration when degrees of necrobiosis are seen in granulomatous infiltrates; therefore, conditions that may be confused include granuloma annulare, some examples of necrobiosis lipoidica, rheumatoid nodule, necrobiotic xanthogranuloma, and lupus miliaris (disseminatus faciei). Each of these has unique morphologic features that are not expected in cutaneous tuberculosis, including mucinous necrobiosis (granuloma annulare), horizontally layered fibrinous necrobiosis alternating with granulomatous foci (necrobiosis lipoidica), subcutaneous lesions with fibrinous necrobiosis, associated with vasculitic changes and a history of arthritis (rheumatoid nodules), and lipidization with foamy macrophages (necrobiotic xanthogranuloma). Lupus miliaris was once considered a tuberculid, shows necrobiosis that has a distinctly caseous appearance, and as in lichen scrofulosorum frequently involves hair follicles. However, these lesions are unassociated with other manifestations of tuberculosis and may have a closer relationship with acne rosacea or perioral/periorbital dermatitis. Mycobacteria are of course not identified in any of these conditions, but they may also be difficult to find in cutaneous manifestations of tuberculosis, requiring PCR or culture studies for confirmation.

However, forms of cutaneous tuberculosis often have little or no caseous necrosis; this is particularly the case in lupus vulgaris and tuberculosis verrucosa cutis. Therefore, granulomatous infiltrates of a variety of types need to be included in the differential diagnosis. These include other infectious diseases, such as atypical mycobacterioses, sarcoidosis, and granulomas of foreign body type. Tuberculids by definition do not show organisms with routine methods, and culture studies are negative. In these difficult circumstances, a diagnosis of tuberculosis requires a high index of suspicion; sometimes the use of PCR technology; and, most importantly, correlation with other clinical and laboratory findings together with an exposure history and possible link to immunosuppression.

Atypical Mycobacterial Infections

Clinical Features: Atypical mycobacteria are pathogenic organisms that are not causes of either tuberculosis or Hansen disease (leprosy). The traditional Runyon classification system for these organisms is based on certain growth characteristics:

• Group I, the photochromogens, produce a yellow color when exposed to light. This group includes two common causes of atypical mycobacterial infection: Mycobacterium marinum and Mycobacterium kansasii.

• Group II, the scotochromogens, also produce a yellow pigment in the dark. The principal organism is Mycobacterium scrofulaceum.

• Group III represents the nonchromogens and includes Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare as well as Mycobacterium haemophilum. Mycobacterium ulcerans is also included in this category.

• Group IV includes the rapid growers, producing colonies in 5 days. The organisms include Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium chelonae, and Mycobacterium abscessus.

Among the atypical mycobacterial infections that involve the skin, three are discussed here: those due to M. marinum, M. chelonae, and M. ulcerans. M. marinum produces a lesion called “swimming pool granuloma,” which describes one potential source of this infection. The organism is found in fish and in both fresh and salt water, and many infections arise in connection with home aquariums. There is usually a history of previous or concomitant trauma to the skin, and acral surfaces, particularly the hands, are usually the sites of infection. Lesions consist of erythematous papules or nodules, which may have hyperkeratotic or verrucous surfaces. Involvement of underlying joints may occur. Sporotrichoid nodules extending up an extremity are sometimes seen, and more extensive disease occurs in immunosuppressed patients. Lesions tend to be persistent without therapy, although spontaneous resolution may occur over the course of a year or so. Treatments include antimicrobial agents such as minocycline and doxycycline.124,125

Infection due to rapid growers such as M. chelonae and M. abscessus follow various forms of trauma, including medical procedures, and have been associated with foot baths in nail salons. The author has observed this type of infection following corticosteroid injections, eventually traced to contaminated multiuse vials. The resulting lesions range from papules to abscesses. The lesions are resistant to the usual antituberculous therapy but generally respond to clarithromycin.126,127

M. ulcerans produces a lesion known as Buruli ulcer. It is actually a common infection worldwide and is endemic in tropical and subtropical countries. The disease typically begins as a subcutaneous nodule on a leg or arm that ulcerates, forming undermined borders, after a period of several months. The ulcers can spread and become quite large and destructive. Although antibiotics are used, treatment often involves local heat therapy or surgical excision.128,129

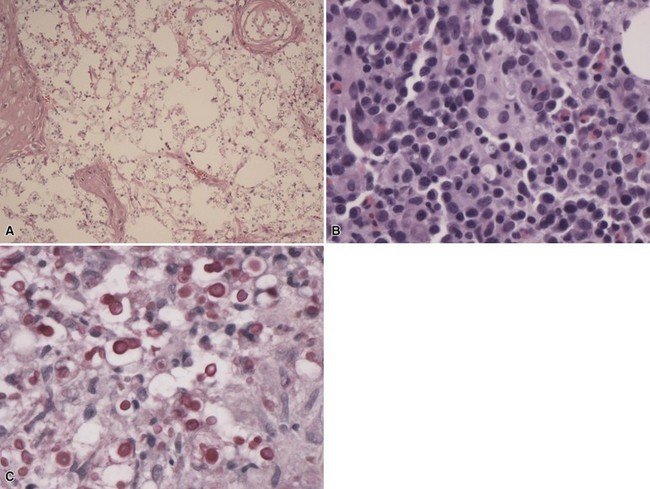

Microscopic Findings: The histopathologic image of M. marinum infection can vary considerably, ranging from a predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate with abscess formation to a patchy lymphocytic and histiocytic (macrophagic) infiltrate to a predominantly granulomatous process. The latter is often loosely organized, and although tuberculoid granulomas can be observed, caseation is generally not seen. Panniculitis can show granulomas mixed with neutrophils, and fat microcysts lined by neutrophils are identified130,131 (Fig. 17-29A-C). Varying degree of acanthosis and even pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia may accompany the dermal changes, and occasionally a blastomycosis-like tissue reaction pattern is observed. Organisms are often difficult to find, even with Ziehl-Neelsen or Fite stains (Fig. 17-30), but may be numerous in immunosuppressed patients (Fig. 17-31). M. marinum organisms are larger and more plump than M. tuberculosis organisms and may have a “beaded” configuration in tissue sections (Fig. 17-32). Immunohistochemical staining for mycobacterial antigen may enhance the likelihood of finding organisms, and PCR methods can also be used.132 Culture studies are useful, but it is essential that cultures be carried out at room temperature for this particular organism.

Figure 17-29 Mycobacterium marinum infection. There is a mixed septal and lobular panniculitis consisting of suppurative granulomatous inflammation (A). Focal granulomas (B) and fat microcysts lined by neutrophils (C) are observed.

Figure 17-30 Atypical mycobacterial infection. Organisms are often sparse but can be identified with acid-fast stains such as the Fite stain.

Figure 17-31 Atypical mycobacterial infection (due to Mycobacterium marinum). With Ziehl-Neelsen stain, numerous organisms are identified within a microcyst lined by neutrophils. These are longer and more plump than Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

Figure 17-32 Atypical mycobacterial infection. “Beading” of organisms is well demonstrated in this example.

M. chelonae infection shows dermal neutrophilic abscesses with granulomatous inflammation, consisting of epithelioid cells with some Langhans-type giant cells. A fistulous tract may extend into the epidermis. Central zones of caseous necrosis have been identified in some cases. Lymphocytes and plasma cells are also observed. Other findings include hemorrhage, fibrosis in later stage lesions, and secondary vasculitic changes. With special stains, organisms can be found in about 25% of cases.133

M. ulcerans infection evolves in three stages. The first consists of widespread tissue necrosis and connective tissue degeneration. The deeper portions of an ulcerated lesion display “ghost-like” outlines of the original tissue structure.134 At this stage, there is minimal inflammation, and organisms are readily identified. This is followed by an organizing stage, in which there are numerous macrophages, plasma cells, and lymphocytes at the margins of necrotic tissue, associated with proliferating capillaries and fibroblasts. Granulomatous elements phagocytose lipid and necrotic cell debris during the healing stage, and mycobacteria become difficult to identify.134,135

Differential Diagnosis: Suppuration with granuloma formation, as seen in M. marinum and M. chelonae infections, should always raise the possibility of infection, and special stains and culture studies are essential. Other bacterial and fungal infections must be considered along with atypical mycobacterial infection and diagnostic studies planned accordingly. In the case of M. marinum infection, a major differential diagnostic consideration is sporotrichosis, because there can be considerable clinical and histopathologic overlap of these infections. This is particularly the case when ascending sporotrichoid nodules are encountered. Because in both infections organisms may be difficult to identify with special staining, culture studies obviously gain in importance. The necrotizing and degenerative appearance of M. ulcerans infections must be distinguished from toxin-mediated lesions, such as spider bites, or from the degenerative changes produced by vascular occlusion (e.g., due to calciphylaxis or antiphospholipid antibodies) or ischemia (e.g., coma bullae). Spider bites, however, show accompanying inflammation, including eosinophils. Thrombosed and/or or calcified vessels provide a clue to other possible causes of tissue degeneration and necrosis, but it must also be pointed out that intimal thickening and occlusion of small arteries have been identified in the periphery of lesions due to M. ulcerans.135 Because numerous organisms can be identified in the latter at an early stage of the infection, special staining (e.g., with Fite stain) can be decisive, and therefore an index of suspicion for mycobacterial infection must be maintained in such cases.

Hansen Disease (Leprosy)

Clinical Features: The numbers of individuals who have leprosy worldwide have diminished substantially in recent years due to ongoing multidrug therapy programs. The areas of greatest prevalence are in Central and South America, Africa, and portions of Asia. This infection is encountered in the United States, especially in areas of Texas and Louisiana and among immigrant populations. The causative agent is Mycobacterium leprae, a small, curved acid-fast bacillus. It tends to be found in macrophages and Schwann cells. Leprosy involves the skin and mucous membranes but also peripheral nerves, bones, and some internal organs. The organisms grow best at temperatures less than 37° C and tend to cause infection in cooler areas of the body.

The classification of leprosy infections is based on the polar division of the various forms of the disease, depending on levels of cell-mediated immunity to the organism. The Ridley and Jopling system for leprosy recognizes the following: lepromatous (at the immunosuppressed end of the spectrum), borderline lepromatous, borderline-borderline (at the midpoint of the spectrum), borderline tuberculoid, and tuberculoid (at the immunocompetent end of the spectrum).136 Indeterminate leprosy may represent the initial presentation of the disease and is capable of resolving spontaneously or progressing to one of the other forms of the disease. The middle stages of the disease are unstable, and patients may move either toward the lepromatous or the tuberculoid pole, depending on the status of their immune systems and/or response to therapy. Lesion types vary according to this classification system. Therefore, indeterminate lesions are often hypopigmented macules, lepromatous lesions range from papules to nodules to diffuse cutaneous infiltration, and tuberculoid lesions feature infiltrated, hypopigmented, anesthetic plaques. There are also reactional states in leprosy. Type I reactions result from change in the immunologic status of the patient, often due to therapy, and can represent reversal reactions (a shift toward the tuberculoid end of the spectrum) or downgrading reactions (a shift toward the lepromatous end of the spectrum). They are associated with swelling of preexisting lesions and neuritis. Type II reactions result from humoral immune reactions in patients with lepromatous leprosy undergoing therapy. The findings include formation of immune complexes and development of small-vessel vasculitis (erythema nodosum leprosum) or, in patients with the diffuse form of lepromatous leprosy, thrombosis with small-vessel vasculitis (Lucio phenomenon). Lepra bacilli have a long doubling time and cannot be cultured, although they can be identified by special staining of tissue samples and by PCR technology.137

Treatments include multidrug antimicrobial therapy. Among the treatments for reactional states are prednisone (for type I reactions and the Lucio phenomenon) and thalidomide (with appropriate precautions) in type II reactions (erythema nodosum leprosum).

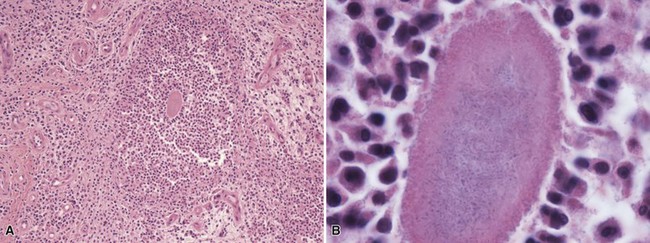

Microscopic Findings: The findings in indeterminate leprosy, as might be suspected, are nonspecific, including patchy perivascular and periappendageal infiltrates composed of lymphocytes and macrophages; organisms are usually not identified.138 In lepromatous lesions, numerous foamy macrophages are seen. Characteristically, larger aggregates are separated from the epidermis by a grenz zone of uninvolved collagen (Fig. 17-33). These macrophages, called Virchow cells, contain numerous organisms surrounded by lipid. Clumps of organisms called globi can also be identified. Lepra bacilli are gram-positive bacteria that also stain red with Ziehl-Neelsen and Fite stains139 (Fig. 17-34 A and B). The histoid variant of lepromatous leprosy consists of fibrotic papules and nodules resembling dermatofibromas; these lesions consist of spindled cells, which also contain numerous acid-fast bacilli that tend to line up along the long axis of the cells140 (Fig. 17-35). In tuberculoid leprosy, there are epithelioid cell granulomas that follow the course of dermal nerves undergoing necrosis; some of these granulomas appear to be elongated or “sausage shaped” when cut longitudinally (Fig. 17-36). Organisms are generally difficult to identify in these lesions but sometimes can be found on careful search. S-100 staining can be useful in identifying fragmented dermal nerve patterns in tuberculoid lesions.141 Varying mixtures of the lepromatous and tuberculoid patterns can be seen in borderline forms of leprosy (Fig. 17-37). Histopathologic shifts toward the tuberculoid or lepromatous ends of the disease spectrum can be seen, respectively, in reversal or downgrading reactions. Erythema nodosum leprosum shows leukocytoclastic vasculitis, sometimes with fragmented bacilli around vessels or within macrophages142 (Fig. 17-38), whereas the Lucio phenomenon shows either necrotizing vasculitis142 or endothelial proliferation and luminal occlusion, with ischemic changes, ulceration, and necrosis.143 Acid-fast organisms can be identified within endothelial cells.

Figure 17-33 Lepromatous Hansen disease. Numerous macrophages are present that contain gray, granular material representing lepra bacilli.

Figure 17-34 Lepromatous Hansen disease. A, With the Fite stain, numerous bacilli can be identified within macrophages and forming globi. B, Lepra bacilli are also positive for Gram stain.

Figure 17-35 Histoid Hansen disease. This spindle cell lesion bears a resemblance to dermatofibroma. Numerous lepra bacilli are identifiable within macrophages.

Figure 17-36 Tuberculoid Hansen disease. Granulomas often show an elongated or “sausage-shaped” configuration, following the course of dermal nerves. Organisms are difficult to identify even with special stains.