Tumors and Tumor-like Conditions Showing Neural, Nerve Sheath, and Adipocytic Differentiation

Patterns of Growth in Neural Proliferations of the Skin

Cutaneous Neural Proliferations

Peripheral Neuroepithelioma/Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor (PNET)

Nonepithelioid Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors

Epithelioid Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors

Pseudotumors of the Skin Related to the Nervous System

Rudimentary Meningocele (Meningotheliomatous Hamartoma)

The following chapter on neural and adipocytic lesions is organized in two ways. First, in keeping with the remainder of this text, a pattern-based paradigm is presented for approaching the diagnosis of proliferations in each of the two categories. Readers will notice straightaway that some lesions appear under more than one pattern heading because of the biologic variation they may exhibit. Second, a categorical discussion of each pathologic entity is presented apart from its potential pattern(s) of growth. One then may thus synthesize the elements of the two expositions to obtain the necessary clinicopathologic information about each lesion.

Patterns of Growth in Neural Proliferations of the Skin

Cutaneous lesions of neural lineage may assume any of four possible growth patterns—circumscribed and well-delimited, circumscribed with “fuzzy” borders, plexiform, and diffusely growing or infiltrative. With few, if any, exceptions, proliferations in the first of these categories are biologically benign, whereas those in the last three groups also may include malignant neoplasms. Listings of the categorical members are shown in Figure 23-1, and exemplary images of the respective patterns are illustrated in Figures 23-2 to 23-5.

Cutaneous Neural Proliferations

Two types of cutaneous neuroma are generally recognized—post-traumatic neuroma1–4 and palisading/solitary-encapsulated (Reed) neuroma (palisaded encapsulated neuroma).3,5–15 Both of those variants manifest as small tan-pink nodules. Post-traumatic neuromas, which are usually painful as well, are often seen on the extremities, where mechanical injuries are most common, whereas palisading neuromas are painless and primarily occur on the face. Both arise predominantly in adults.

Ganglioneuromas rarely originate in the skin16–24 and more usually are found in mucosal surfaces such as the lips, mouth, and conjunctiva. They are largely restricted to patients with the multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome, type 2b (Gorlin syndrome),25 in which medullary thyroid carcinoma, pheochromocytoma, parathyroid hyperplasia, and a marfanoid habitus are also present. Mucosal ganglioneuromas are typically multiple, irregular nodules of variable size. Rare cases of solitary ganglioneuroma have been reported, sometimes using the rubric of “ganglion cell choristoma.”26 They appear as nondescript, tan, firm nodules.

Post-traumatic “neuromas” are misnamed, because they are not truly neoplasms but rather the result of aberrant attempts at renervation after traumatic disruption of neural axons.1 One observes a proliferation of banal nerve bundles that are distorted by intersecting and encompassing fibrous bands. Regenerating axonal fibers are “blocked” from establishing continuity with distal portions of the axon by the fibrosis, yielding micronodular proliferations of nerves and accompanying Schwann cells. Adjacent blood vessels may contain organizing microthrombi.

Palisading neuromas are actual neoplasms. They are centered in the mid-dermis, with a peripheral thin fibrous capsule. Fascicles of bland, amitotic spindle cells are separated by artifactual clefts and intertwined around one another; no fibrous sheaths surround them. Tumor cell nuclei in palisading neuromas show a tendency to align themselves in register inside each fascicle (Figs. 23-6 and 23-7). Nuclear contours are sometimes serpiginous, as the profiles of individual cells also may be. Cytoplasm is amphophilic. However, palisading neuroma lacks the intracellular fibrillation, cytoplasmic eosinophilia, and blunt-ended nuclear profiles that would be expected in benign smooth muscle tumors, which represent the principal diagnostic alternative. Similarly, tumor cell fascicles in palisading neuroma do not show the zones of perinuclear cytoplasmic clarity that are seen in leiomyomas.

Figure 23-6 Palisading neuroma of the facial skin is shown here as a small papular lesion on the upper lip.

Figure 23-7 Solitary circumscribed (palisading; Reed) neuroma of the skin shows an attenuated fibrous capsule surrounding a fascicular proliferation of bland spindle cells (top left) that tend to demonstrate nuclear palisading (top right). In contrast, traumatic neuroma is a pseudoneoplastic reaction to neural injury that demonstrates random proliferation of nerve fibers in the dermis (bottom left and right).

Ganglioneuromas differ from the description just given because they are not encapsulated, and they contain well-formed ganglion cells interspersed throughout the lesions (Fig. 23-8). The latter elements are easily recognized by their polyhedral shape, vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. Franchi and colleagues27 studied a case showing notable stromal desmoplasia. Drut and associates28 also have documented a case of giant congenital nevus that contained an extensive zone of ganglioneuromatous differentiation. Differential diagnosis may center on the possibility of ganglioneuromatous “maturation” of metastatic neuroblastoma in the skin,29 but the clinical setting typically makes that distinction a straightforward one.

Neurofibroma

Neurofibromas of the skin are relatively common sporadic neoplasms, in which case they are nondescript soft papules or nodules measuring up to 3 cm in diameter (Fig. 23-9). Any skin field may be affected as well as patients of all ages.14,30–34

Figure 23-9 Clinical photograph of solitary neurofibroma, showing a nondescript, soft, raised, nodular lesion in the skin of the trunk.

Multiple neurofibromas (Fig. 23-10)—particularly if they are accompanied by “café au lait” lesions and develop before 10 years of age—strongly suggest a diagnosis of von Recklinghausen disease (neurofibromatosis, type 1 [NF1]).34–38 The plexiform variant of these neoplasms, which is regarded as presumptive evidence of von Recklinghausen disease even if solitary (Fig. 23-11), may attain a size of more than 20 cm. It can greatly distort the superficial soft tissue, so that the affected skin acquires a pendulous appearance (“elephantiasis neuromatosa”). The cut surface of plexiform neurofibromas is sometimes said to resemble a “bag of worms.”

Figure 23-10 Clinical photograph of a patient with von Recklinghausen disease (neurofibromatosis type 1). Multiple raised nodules are present in the skin of the arm.

Figure 23-11 Clinical photograph of another patient with von Recklinghausen disease and a plexiform neurofibroma (left), which has a multicompartmental appearance like that of “waves against the shore.” The excised neoplasm (right) resembles a distorted nerve plexus on gross examination.

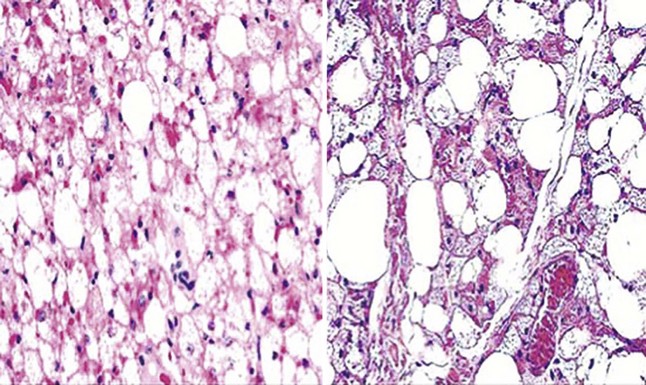

Neurofibromas are cytologically bland spindle cell tumors with serpiginous nucleocytoplasmic contours. Solitary nodular forms of these neoplasms are usually circumscribed but not encapsulated, although a “diffuse” variant exists that shows a tendency to blend with the surrounding dermis or soft tissue. These lesions are usually uniform microscopically (Fig. 23-12), and they may be restricted to the corium or extend deeply into the subcutis. Myxoid stromal change is common, but a tendency toward nuclear palisading is not. The tumor cells are arranged haphazardly, in thin fascicles, or in a vaguely storiform pattern, with entrapment of dermal collagen, appendages, and fat. The last of those phenomena has led to the use such diagnostic terms as “lipomatous neurofibroma”39–41 (Fig. 23-13). Intralesional mast cells are often numerous. Variants include tumors with partial melanization of the tumor cells,42,43 and a peculiar subtype called “dendritic cell neurofibroma with pseudorosettes.” This lesion is a dermal spindle cell neoplasm that also contains many circular aggregates of tumor cells encompassing stromal material.44,45

Figure 23-12 Photomicrograph of solitary neurofibroma, showing an ill-defined proliferation of cytologically bland spindle cells in the dermis. The background stroma is vaguely myxoid.

Figure 23-13 Prominent entrapment of fat by neurofibromas, as shown here, may lead to diagnostic confusion of such lesions with adipocytic neoplasms.

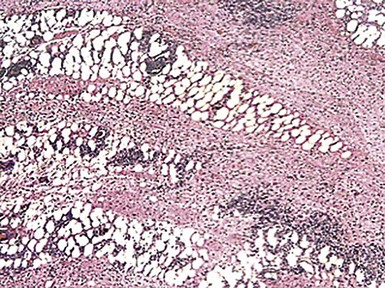

On the other hand, plexiform neurofibroma has a distinctive configuration like that of a distorted neural plexus. Irregular fascicles of proliferating but banal Schwann cells are separated from one another by myxofibrous stroma or adipose tissue, such that each grouping of spindle cells resembles a miniature nerve trunk46,47 (Fig. 23-14). Occasionally, structures resembling meissnerian or pacinian corpuscles may be seen as well.48 To reiterate, making a histologic interpretation of plexiform neurofibroma strongly suggests a diagnosis of NF1; hence, one should be strict about that interpretation.

Figure 23-14 Microscopically, plexiform neurofibromas are made up distinct multifascicular congeries of spindle cells in the dermis and subcutis.

Mitotic activity, local hypercellularity, necrosis, and nuclear atypia are worrisome features in lesions thought to be neurofibromas. It is well-known that it may be difficult to distinguish such neoplasms from selected low-grade malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNSTs), particularly if they are several centimeters in size.37,47,49,50 Therefore, diagnostic reports on atypical neurofibromatous lesions that have been only partially sampled may use the term “peripheral nerve sheath tumor of indeterminate biologic potential.” Several studies have suggested that positive immunostains for mutant p53 protein and Ki-67 may be helpful in separating MPNSTs from other nerve sheath tumors, which lack those markers.51,52 The dendritic neurofibroma with pseudorosettes44 may be confused with another malignant neoplasm; namely, primitive neuroectodermal tumor/extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma.53 However, dendritic neurofibroma with pseudorosette lacks CD99 and contains zones of spindle cell growth, and both of those features are not expected in primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET).

An additional problem concerning neurofibromas is their distinction from ordinary but extensively “neurotized” melanocytic intradermal nevi, as well as amelanotic and neuroid variants of blue nevus or Spitz nevus.46,54–57 Serial sections are often required to search for small foci of obvious melanocytes in those nevocytic lesions, and it is admittedly impossible to make the cited distinction in some cases. A pragmatic approach to this problem is to rely on the “rule of association.” If a single polypoid lesion is present with a neural histologic image, the diagnosis is that of neurofibroma; on the other hand, if the patient in question also has several melanocytic nevi, the best interpretation is that of a neurotized nevus. Most neurofibromas and neurotized nevi share immunoreactivity for S-100 protein, but only neurofibromas express factor XIIIa (Fig. 23-15) in that narrow differential diagnosis.

Figure 23-15 Neurofibromas are immunoreactive for factor XIIIa, as depicted here, unlike neurotized melanocytic nevi, which they may imitate histologically.

As an aside, Weiss and Nickoloff have shown that neurofibromas commonly express CD34,58 and, in the authors’ consultation practice, this fact has been the source of concern, prompting the referral of several cases. Schwannomas (see later discussion) share the same potential for CD34 reactivity. Even more problematically, occasional neurofibromas may lack immunopositivity for S-100 protein, CD56, and CD57, which is seen in the great majority of cases, and instead they manifest only labeling for CD34.

Another possible differential diagnostic consideration is that of perineurioma, a form of peripheral nerve sheath tumor (PNST) that is characterized by stacked, lamellated, or concentric configurations of spindle cells.59,60 Like neurofibroma, this neoplasm also may assume a plexiform configuration, and a sclerotic variant exists as well. Perineurioma is recognizable as such by its immunoreactivity for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and claudin-1, as well as its typical morphologic images (see subsequent discussion).61

Several other cutaneous tumors may assume a plexiform appearance. These include Spitz nevi, plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumors, and plexiform dermatofibromas. None of those lesions occurs in patients with NF1, and their immunohistologic profiles—as presented elsewhere in this book—are dissimilar to those of neurofibromas. Plexiform schwannomas are discussed later.

Neurilemmoma (Schwannoma)

Neurilemmomas (schwannomas) are essentially identical to sporadic neurofibromas on clinical grounds (Fig. 23-16). There is a potential association between cutaneous variants of schwannoma and von Recklinghausen disease if the lesions are multifocal and grossly plexiform (Fig. 23-17); however, this is rare.47,62–65

Figure 23-16 Clinical photograph of cutaneous neurilemmoma, showing a fleshy nodular lesion that protrudes above the skin surface.

Figure 23-17 An unusual finding in cutaneous neurilemmoma is the presence of macroscopic (left) and histologic (right) plexiform features in the lesion. This finding is only rarely associated with von Recklinghausen disease, unlike the situation with plexiform neurofibroma.

Neurilemmomas differ from neurofibromas in two major respects. First, they demonstrate a biphasic cellular growth pattern. Second, they are often encapsulated and contain thick-walled stromal blood vessels.14,31

The two major microscopic patterns in neurilemmoma are known as the “Antoni A” and “Antoni B” configurations. These feature the presence of dense spindle cell foci with potential nuclear palisading (Verocay bodies), and myxoid or edematous, paucicellular areas composed of bland stellate tumor cells, respectively47,66 (Figs. 23-18 and 23-19). Nuclear characteristics are usually bland, although traumatized, long-standing superficial (“ancient”) neurilemmomas can show nuclear enlargement and hyperchromasia as secondary changes (Fig. 23-20). Mitotic activity is scanty, and, unlike the case with neurofibroma, some division figures may be “tolerated” without undue worry over possible malignancy. Indeed, malignant change in schwannomas is vanishingly rare,67 and is, for practical purposes, restricted to very large and deep-seated tumors.

Figure 23-18 Neurilemmoma of the skin, demonstrating the microscopic juxtaposition of compact cellular (“Antoni A”) areas and zones of loose fibromyxoid (“Antoni B”) tissue.

Figure 23-19 A focus of “Antoni A” growth, with a tendency toward nuclear palisading, is present on the right side of this illustration of a dermal neurilemmoma. On the left side, loosely arranged “Antoni B” tissue is present.

Figure 23-20 “Ancient” neurilemmoma shows notable nuclear pleomorphism and hyperchromasia, in the absence of mitotic activity or alterations in nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios. This change is degenerative in nature and has no prognostic significance.

Neurilemmoma is much more “versatile” than other PNSTs with respect to its range of microscopic differentiation. Variants of this neoplasm include one containing small groups of epithelium, with or without mucin production (“glandular” neurilemmoma)68,69 (Fig. 23-21); another showing an admixture of melanized cells (“melanotic” neurilemmoma)64,70,71 (Fig. 23-22); a plexiform subtype in which the macroscopic appearance of the tumor simulates that of plexiform neurofibroma (see earlier discussion)46,64,72–74; a variant dominated by plump epithelioid tumor cells (“epithelioid” neurilemmoma)75–77; and a form in which both melanin and psammomatous calcification are apparent (“psammomatous-melanotic” neurilemmoma).78 Some observers use the term “cellular schwannoma” in describing some cutaneous tumors with extremely dense “Antoni A” areas. However, the latter designation is most properly applied to a restricted subset of neurilemmomas that occur in the deep soft tissues of the midline.79

Figure 23-21 True glandular tissue may be apparent in cutaneous neurilemmoma (left). This feature is likely metaplastic in nature. Diffuse epithelioid change (right) is a variation on the same theme.

Figure 23-22 Densely pigmented cytoplasm is evident in the tumor cells of this melanotic neurilemmoma. Lesions such as this one may be black or brown grossly.

Another peculiar form of cutaneous schwannoma is that represented by so-called neuroblastoma-like neurilemmoma.80,80a,81 It was named as such because of a composition by small ovoid cells that often enclose fibrillary material resembling neuropil (Fig. 23-23). However, unlike metastatic neuroblastoma, neuroblastoma-like neurilemmoma is strongly and diffusely immunoreactive for S-100 protein and vimentin. Conversely, it lacks affinity for the antibody known as NB84 and fails to label for synaptophysin.82–84

Figure 23-23 “Neuroblastoma-like” neurilemmoma is made up of aggregates of small, compact ovoid cells that surround fibrillary aggregates in the dermis. The overall image resembles that of a neuroectodermal neoplasm.

Cutaneous smooth muscle tumors occasionally may show variation in cellular density and some nuclear palisading, mirroring the attributes of neurilemmoma. However, leiomyomas are consistently immunoreactive for desmin, actin, caldesmon, and calponin, and only sporadically positive for S-100 protein; schwannomas show the converse of that profile. Examples of “neuroid” basal cell carcinoma with prominent nuclear palisading have also been reported by San Juan and coworkers85; they demonstrated immunoreactivity for keratin and a lacking for neural determinants.

Neurothekeoma

Like other pathologic entities, the tumor now known as neurothekeoma has undergone substantial conceptual metamorphosis since its original description.86 Relatively shortly thereafter, an alternate term for a putatively related superficial soft tissue tumor—dermal nerve sheath myxoma—was introduced.87 Diagnostic complexity in this group of lesions was further amplified by publications on a lesion called “cellular” neurothekeoma, originally described by Rosati and colleagues in 1986.88–90 The authors consider each of these tumor types to represent a distinct and mutually exclusive neoplasm, as substantiated by the results of immunohistologic and electron microscopic studies. However, that is not necessarily the opinion of other observers.

Lesions currently grouped under the rubric of “neurothekeoma” and “dermal nerve sheath myxoma” primarily affect young individuals, with a mean age of 22 years. Females predominate by a ratio of 2 : 1, and the tumors are most often located on the face, shoulders, and arms. They are tan or pink, variably firm, dome-shaped papules or nodules, sometimes with a translucent quality86–93 (Fig. 23-24).

Figure 23-24 Clinical photograph of cutaneous neurothekeoma of the nasal skin in a young woman (left). The excised tumor has a multinodular cut surface (right).

In the authors’ opinion, the term “neurothekeoma” is best used in reference to a tumor that is composed of bland to moderately atypical plump spindle cells and epithelioid elements in the dermis, which simulates the formation of melanocytic theques (Fig. 23-25). Mitoses may be easily seen in these lesions, but they are never pathologic in shape. In contrast, dermal nerve sheath myxomas are obviously mucomyxoid tumors showing concentric proliferations of spindle cells that are separated by matrical material (Figs. 23-26 and 23-27). Nuclear atypia and mitotic figures are variable but usually inconspicuous. Cellular neurothekeoma, on the other hand, is represented by solid dermal aggregates of epithelioid, vaguely nevoid cells, with a more indistinct nesting pattern (Fig. 23-28). Those neoplasms again may manifest moderate nuclear hyperchromasia, and mitotic figures are present. Plexiform and desmoplastic variants of cellular neurothekeoma have been described as well.46,93a

Figure 23-25 Concentric profiles of bluntly fusiform and cytologically bland tumor cells typify the microscopic appearance of “classical” cutaneous neurothekeoma.

Figure 23-26 Dermal nerve sheath myxoma, consisting of nested arrays of bland spindle cells that contain abundant fibromyxoid stroma.

Figure 23-27 Rounded configurations of fusiform tumor cells are set in a fibromyxoid matrix in this dermal nerve sheath myxoma (left). The tumor is immunoreactive for S-100 protein (right).

Figure 23-28 Cellular neurothekeoma shows a much less organoid growth pattern than that of classical neurothekeoma or dermal nerve sheath myxoma. Moderate nuclear pleomorphism, relative dense cellularity, and at least focally confluent growth are present.

Immunohistologically, evidence exists to support the contention that dermal nerve sheath myxoma shows schwannian or perineurial cell differentiation, because it is variably reactive for S-100 protein, CD57, and EMA.94,95 In contrast, all of those markers are absent in classical neurothekeoma and “cellular” neurothekeoma. The last of these lesions is further distinguished by its potential positivity for alpha-isoform actin, as well as NKI/C3, microphthalmia transcription factor, S-100 protein isoform-A6, neuron-specific enolase, factor XIIIa, and podoplanin (Fig. 23-29). Hence, cellular neurothekeoma exhibits an immunohistologic nexus between melanocytic and “fibrohistiocytic” neoplasms.

Figure 23-29 Immunoreactivity for S-100A6 protein (left) and podoplanin (with antibody D2-40 [right]) is characteristic of cellular neurothekeoma.

Ultrastructural studies of dermal nerve sheath myxoma also have shown evidence of nerve sheath differentiation—as manifested by production of pericellular basal laminar material and the presence of elongated and partially overlapping cellular processes.91 These characteristics are not present in either neurothekeomas or “cellular” neurothekeomas.

The differential diagnosis of neurothekeoma principally centers on plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor, epithelioid neurofibroma, epithelioid neurilemmoma, and low-grade epithelioid MPNST (EMPNST) of the skin and subcutis, as well as dermal epithelioid (Spitz) nevi and “nevoid” melanoma. Most of those entities can be distinguished from one another by immunohistologic studies.90,95–97 Neurofibroma, schwannoma, and melanocytic nevi are universally reactive for S-100 protein, and a sizable proportion of melanocytic proliferations—both benign and malignant—express the HMB-45 antigen, MART-1/Melan-A, and tyrosinase. On the other hand, neurothekeomas lack all of those determinants. Although Jaffer and associates98 have suggested that plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor 99 (Fig. 23-30) and cellular neurothekeoma are part of a single pathologic continuum, Kaddu and Leinweber100 and Fox and coworkers101 found clear-cut immunohistochemical differences between them. In the latter studies, all cellular neurothekeomas expressed podoplanin and microphthalmia transcription factor, whereas no example of plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumor did so.

Figure 23-30 Plexiform fibrous histiocytoma (PFH), as shown here, is microscopically similar to plexiform cellular neurothekeoma, but the two neoplasms are distinct. PFH contains osteoclast-like giant cells (lower two panels), unlike neurothekeomas, and it also lacks podoplanin and S-100A6.

Neurothekeoma is allowed to manifest some nuclear hyperchromasia as well as mitotic activity, without any connotation of malignancy. However, the presence of spontaneous necrosis, striking cellular pleomorphism, or pathologically shaped division figures instead suggest an alternative diagnosis of melanoma or EMPNST.

The treatment for neurothekeoma is simple excision. The lesions do not recur, providing that they have been completely removed. Busam and colleagues102 studied 10 examples of neurothekeoma that showed a size greater than 6 cm, deep growth into the subcutis or skeletal muscle, infiltrative borders, vascular invasion, brisk mitotic activity, and notable cytologic atypia. Despite such features, none of those lesions behaved adversely.

Perineurioma

Perineuriomas are PNSTs that demonstrate differentiation toward perineurial fibroblasts rather than Schwann cells. Until 25 years ago, they were generally labeled as “unclassifiable” PNSTs, but the availability of electron microscopy and immunohistology allowed for recognition of a perineurial lineage.60,61

Clinically, perineuriomas are nondescript cutaneous nodules that measure up to 3 cm in maximum dimension, and they are generally seen on the extremities of adults. Some may be tender on palpation.

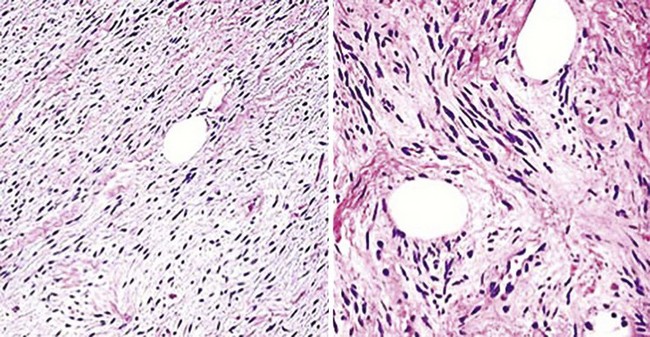

The microscopic image of most perineuriomas is that of a bland spindle cell proliferation in the dermis, in which the lesional cells are stacked in a lamellated fashion or in concentric formations (Fig. 23-31). Growth within dermal nerves may also be apparent. Nuclei are small and fusiform, and cytoplasm is attenuated. Histologic variants of this tumor include a sclerosing form, one with granular cell change, and others with reticular or plexiform growth patterns.60,61,103,104 Composite neoplasms with features of both perineurioma and granular cell tumor or schwannoma have also been reported.105,106

Figure 23-31 Perineuriomas of the skin show a concentric or lamellated arrangement of cytologically bland spindle cells in the corium (upper two panels). Sclerosing (bottom left panel) and granular cell variants of this tumor also exist. All perineuriomas are immunoreactive for epithelial membrane antigen (bottom right panel).

In keeping with the attributes of non-neoplastic perineurial fibroblasts, perineuriomas are immunoreactive for EMA, claudin-1, and GLUT-1 but not for CD34, factor XIIIa, S-100 protein, CD56, or CD57.61 That immunoprofile serves to distinguish them from other differential diagnostic considerations, which include fibrous histiocytomas; meningothelial proliferations; fibromas of tendon sheath; and desmoplastic, hypopigmented melanocytic nevi.

Granular Cell Tumor

Granular cell tumors of the skin are tan, dome-shaped nodules with smooth surfaces, measuring up to 3 cm in greatest dimension (Fig. 23-32). They occur at all ages and in all topographic locations,107–109 and they may be multifocal.107

Figure 23-32 Cutaneous granular cell tumor, manifesting as an umbilicated erythematous nodule in the skin of the arm (left). The cut surface of the excised lesion demonstrates internal irregularity and involvement of the subcutis (right).

The hallmark of granular cell tumor is its exclusive composition by polyhedral cells with eccentric oval nuclei; dispersed nuclear chromatin; and overtly granular, lightly eosinophilic cytoplasm.108,109 The overlying epidermis is typically induced to proliferate, sometimes producing such striking pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia that a diagnosis of squamous carcinoma might be considered in small superficial biopsies. The neoplastic cells permeate the dermis irregularly, entrapping collagen bundles and cutaneous adnexa, and they often extend into the superficial subcutis (Fig. 23-33). The scanning microscopic appearance of this lesion is usually circumscribed but not encapsulated.110,111 Variant growth patterns include a notably infiltrative one112 and a plexiform subtype.113 Rare mitotic figures may be seen in granular cell tumors, the cells of which are monotonous with bland nuclear features and abundant cytoplasm (Fig. 23-34). Atypical division figures, necrosis, vascular permeation, and overlying ulceration should prompt one to consider the possibility of a malignancy.114

Figure 23-33 Microscopically, cutaneous granular cell tumor occupies the entirety of the corium and shows a disorganized growth pattern that “dissects” through the dermal collagen.

Figure 23-34 The neoplastic cells in cutaneous granular cell tumor are cytologically bland, with prominent cytoplasmic stippling and slightly eccentric compact nuclei.

Justification for including granular cell tumor with nerve sheath lesions is obtained from data on its ultrastructural features and immunohistologic attributes.115 Most neoplasms of this type (approximately 85%) show electron microscopic evidence of schwannian differentiation115,116; likewise, immunoreactivity for S-100 protein, calretinin, CD56, and CD57 links such lesions to other neural lesions.115,117

As mentioned earlier, a granular cell variant of perineurioma also has been documented.105,106 That lesion labels for EMA, but it is non-reactive for all schwannian markers.

In a minority of cases, granular cell change may simply be a nonspecific degenerative alteration—reflecting an abundance of secondary cytoplasmic phagolysosomes (Fig. 23-35)—in other neoplasms that are not neural in nature, such as dermatofibroma, atypical fibroxanthoma, melanoma, leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, angiosarcoma, and basal cell carcinoma.115,118–125 Granular cell variants of those lesions do not differ in behavior from their conventional incarnations.

Peripheral Neuroepithelioma/Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumor (PNET)

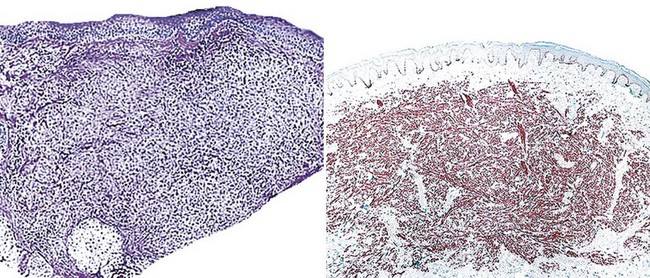

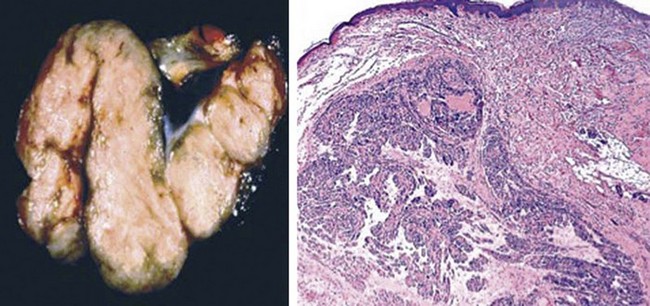

Peripheral neuroepithelioma126 (formerly called “extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma” and now preferentially known as PNET127–142) is rarely encountered in the superficial subcutis and dermis (Fig. 23-36), where it presents as a nodular, red-violet, ill-defined mass. Patients with PNET are usually children, adolescents, or young adults, but older individuals are occasionally affected as well. The neoplasms may attain a maximum dimension of 10 cm and are rapidly growing. The trunk and proximal extremities are favored locations for PNET.138–142

Figure 23-36 Clinical (left) and gross (right) photograph of subcutaneous primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the foot, demonstrating a multinodular and fleshy lesion with relative circumscription.

The clinical behavior of this tumor is an aggressive one when it is situated in the deep soft tissues. Even with prompt diagnosis and therapy, that form of PNET is associated with a five-year disease-free survival of only 60%; distant metastases to lungs, liver, bones, and brain are common.133 However, cutaneous and subcuticular PNET appears to have a more favorable evolution, based on treatment results seen with a relatively smaller number of accrued cases.138,139,141,142

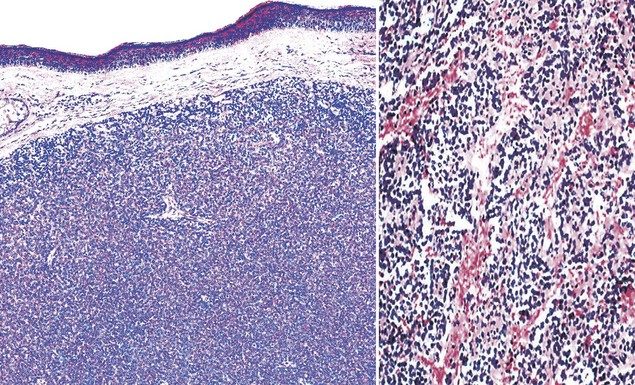

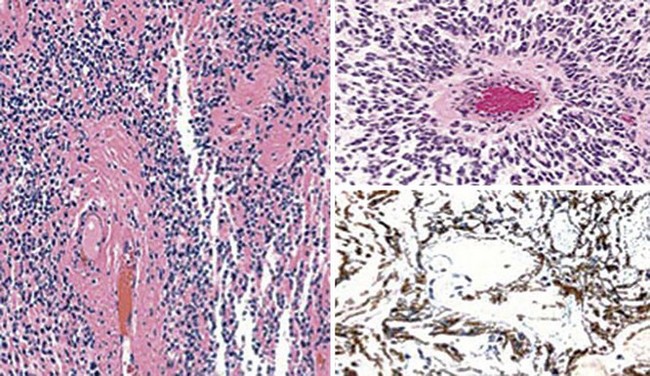

PNET represents one of the prototypical small round cell tumors. It assumes the form of sheets, vague nests, and cords of closely apposed monomorphic neoplastic cells that are approximately two to three times the size of mature lymphocytes (Figs. 23-37 and 23-38). Cellular aggregates are separated from one another by a delicate but complex fibrovascular stromal network. Mitotic activity is variable but may be surprisingly sparse; similarly, apoptosis and regional necrosis may or may not be present.

Figure 23-37 Photomicrograph of dermal and subcutaneous primitive neuroectodermal tumor, showing a composition by monotonous small round cells that focally form vague rosettes (left). The neoplasm has a rich fibrovascular stroma, with extravasated erythrocytes (right).

Figure 23-38 The neoplastic cells in primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the skin are relatively uniform, with dispersed chromatin and relatively sparse mitotic activity.

The nuclear detail of PNET is one of the most helpful clues to its recognition. Nuclear membranes are smooth with round to ovoid contours; chromatin is typically evenly distributed; and nucleoli, if they are present at all, are small. Cytoplasm is scant and amphophilic.

A minority of PNET cases exhibit the presence of intercellular rosettes, betraying the primitive neural nature of this neoplasm.126 However, the fibrillary intercellular meshwork seen in some examples of metastatic neuroblastoma143—an important differential diagnostic alternative—is lacking in PNET. Similarly, nuclear pleomorphism or multinucleation are uniformly absent, in contrast to the characteristics of rhabdomyosarcomas.144 Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) enters into diagnostic consideration, because the latter tumor may occasionally arise in the deep corium or subcutis.145 Merkel cell tumors are somewhat related to PNET in regard to cellular differentiation, and electron microscopy or immunohistology are often necessary to obtain a final distinction between them. PNET is typified by immunoreactivity for CD99 (Fig. 23-39) and FLI-1; negativity or only focal labeling for pankeratin; and an absence of actin, desmin, microtubule-associated protein-2 (MAP-2), EMA, and keratin-20.55,138,146 On the other hand, MCC is diffusely reactive for pankeratin; 85% to 90% also label for keratin-20 and EMA. CD99 may be observed in approximately 50% of Merkel cell tumors. Neuroblastoma is uniformly negative for CD99, and it reacts for MAP-2; rhabdomyosarcoma is consistently positive for muscle-specific actin, with or without desmin.147

Figure 23-39 Diffuse and intense immunoreactivity for CD99 is present in subcutaneous primitive neuroectodermal tumor.

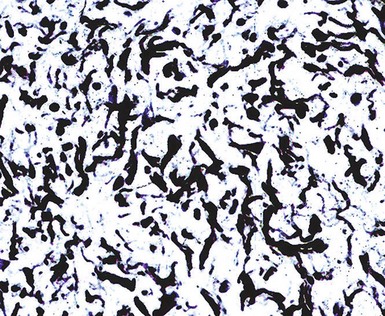

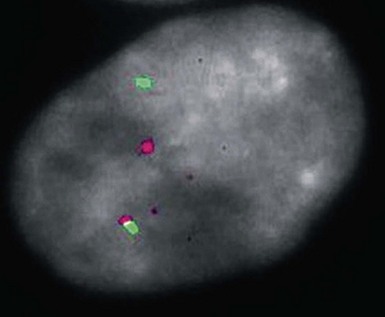

Cytogenetic or polymerase chain reaction (PCR)–based molecular analysis in this group of lesions shows a t(11;22) chromosomal translocation in PNET140,148 (Fig. 23-40); abnormalities of chromosomes 1 and 6 in Merkel cell tumors; and aberrations of chromosomes 1, 11, and 17 in neuroblastomas. Allelic losses at 11p or t(1;13) or t(2;13) translocations are expected in rhabdomyosarcomas.149–152

Figure 23-40 In situ hybridization study with fluorescent probes for the EWS gene (red) and the FLI-1 gene (green) in primitive neuroectodermal tumor of the subcutis. In this tumor cell, there is a clear separation of one copy of each gene, representing translocation of portions of chromosomes 11 and 22.

Malignant lymphomas of the subcutis also may simulate any of the other small-cell neoplasms, including PNET. The nuclei of lymphoid cells differ from those in other diagnostic alternatives, because they are more irregular in contour and have a greater tendency to overlap one another.153 Nevertheless, the most certain indicator of hematopoietic differentiation is the CD45 antigen, which is seen only in lymphoproliferative lesions.147

Nonepithelioid Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors

Outside the context of NF1, the existence of cutaneous MPNSTs has been questioned in the past. It is well-recognized that approximately 1% to 3% of patients with von Recklinghausen disease—both children and adults—develop malignant transformation in superficial neurofibromas, in which cases the latter lesions rapidly expand in size and can become painful.37,154,155

Sporadic cutaneous MPNSTs have been accepted as bona fide entities increasingly over the past few years, even though they are exceedingly difficult to discriminate from neuroid melanomas diagnostically. The former lesions are nodules or plaques with variable growth rates, and they have a propensity to arise on the trunk or extremities of adults.156,157 Ulceration may supervene (Fig. 23-41), and local paresthesias or dysesthesias can appear if the masses are associated with major nerves.

Figure 23-41 Cutaneous malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, presenting as an ulcerated plaquelike lesion in the skin of the hand.

The behavior of MPNSTs is determined by their size, location, and surgical resectability. However, those arising in the skin more often demonstrate local recurrence (in approximately 80% of cases) than distant metastasis (15% to 20%).157,158

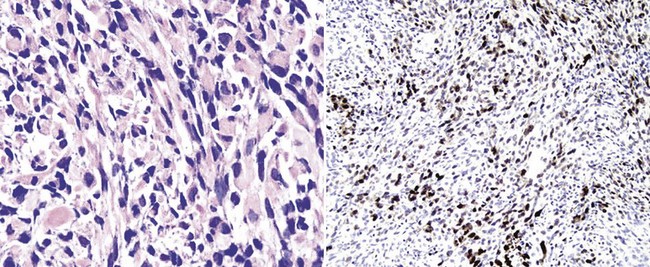

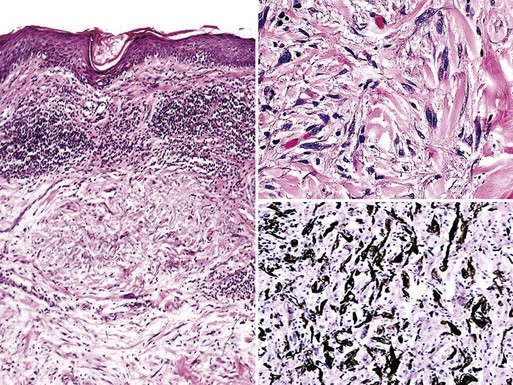

The microscopic features of MPNSTs are variable; indeed, these neoplasms are among the great “chameleons” of pathology. In most instances, one observes a modestly pleomorphic proliferation of spindle cells, in which cellularity is variable from region to region (Fig. 23-42). The tumor cells are randomly arranged or configured in fascicles that may intersect one another at acute angles (the so-called “herringbone” growth pattern), and many contain “wavy” or serpiginous nuclei (Fig. 23-43). Myxoid stromal change is evident in approximately one third of all cases, and a focally storiform arrangement of tumor cells is often observed as well.50,157,159

Figure 23-42 A haphazard growth of atypical spindle cells is present in the dermis in this cutaneous malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (upper left). Nuclear atypia and variation in cellular density are apparent within the mass (upper right; lower left).

Figure 23-43 “Serpiginous” or elongated nuclei are apparent in this malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor of the skin.

These lesions entrap cutaneous appendages rather than destroying them, but the peripheral margins of growth are indistinct. Permeation into the underlying soft tissue is common. Nuclear atypia is modest to moderate, and mitotic activity is present but not striking.

Occasional examples of cutaneous MPNSTs—particularly those occurring in patients with von Recklinghausen disease—exhibit divergent mesenchymal differentiation. Tumors showing an admixture of rhabdomyosarcomatous elements with the spindle cell population are known as “malignant triton tumors”160–162 (Fig. 23-44). Although de novo rhabdomyosarcoma is a highly aggressive neoplasm, triton tumors are, paradoxically, no different biologically than conventional MPNSTs. Other divergent elements that have been reported in such lesions include those resembling osteosarcoma, pigmented malignant melanoma (“melanotic MPNST”), chondrosarcoma, adenocarcinoma (“glandular MPNST”), and angiosarcoma.157,158

Figure 23-44 This malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) of the skin demonstrates divergent rhabdomyoblastic differentiation, represented by neoplastic cells with notably eosinophilic cytoplasm (left). This variant of MPNST is known as “malignant triton tumor.” Immunoreactivity for myogenin (right) confirms the presence of striated muscle elements in the lesion.

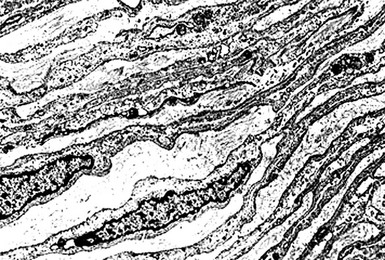

Electron microscopic evaluation demonstrates elongated, overlapping cytoplasmic processes in the spindle cells of MPNST (Fig. 23-45). Focal formation of pericellular basal lamina is also common, as are primitive appositional plaques between adjacent tumor cells. Cytoplasmic type 1, 2, and 3 premelanosomes are absent.

Figure 23-45 Electron photomicrograph of cutaneous malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, demonstrating elaborately overlapping and attenuated cytoplasmic processes that are invested by basal lamina. Premelanosomes are absent.

Immunohistologic studies show reactivity for CD56 in 60% of cases, S-100 protein in approximately 50%, and CD57 in 33%47,147,163,164 (Figs. 23-46 and 23-47). When used as a panel, one or more of these markers is present in 70% to 75% of all lesions. Histologically divergent tumors also may express desmin or muscle-specific actin, keratin, CD31, CD34, or FLI-1. Collagen type IV and laminin are also commonly present in MPNSTs.

Figure 23-46 Immunoreactivity for S-100 protein (left) and CD56 (right) in malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor of the skin.

Figure 23-47 Positivity for mutant p53 protein (left) and collagen type IV (right) in cutaneous malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor.

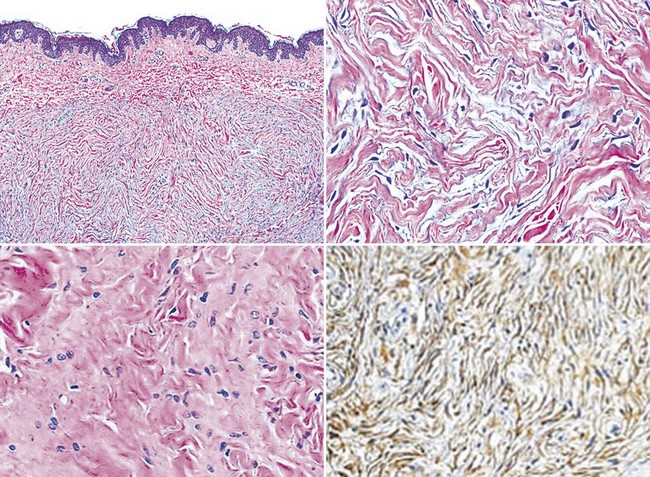

Differential diagnosis includes leiomyosarcoma, spindle cell squamous carcinoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP), atypical fibroxanthoma, and desmoplastic or neurotropic melanoma. All but the last of those possibilities can be adequately distinguished from MPNST by electron microscopy and immunohistology.47 Nevertheless, “neuroid” spindle cell melanomas and true nerve sheath tumors share many points of pathologic synonymity.165–167 Ultrastructural features of the two groups are virtually identical, because spindle cell melanomas fail to demonstrate cytoplasmic premelanosomes.168 Similarly, HMB-45, MART-1/Melan-A, PNL2, and tyrosinase—specific determinants of melanocytic cells—are absent in virtually all neuroid melanomas and are likewise not seen in MPNSTs.169 Thus, one may not be able to make the distinction between neuroid melanoma and cutaneous MPNST with certainty, in the absence of a concurrent or previous intraepidermal melanocytic proliferation (Fig. 23-48). Whether such a separation of the two tumors is necessary is also a contentious point, because of similarities in their biologic potential and behavior.165

Figure 23-48 “Neuroid” spindle cell melanoma is closely similar morphologically to malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor of the skin. However, the former neoplasm, shown here, may demonstrate the presence of atypical melanocytic proliferation at the dermoepidermal junction, and it also manifests more global immunoreactivity for S-100 protein (lower right panel).

Pending resolution of this issue, the authors presently require that a diagnosis of sporadic cutaneous MPNST should be made only under narrowly defined circumstances. An epidermal melanocytic lesion must be absent; electron microscopy and immunohistology must both be performed, and the results of those studies should not show the presence of melanocytic differentiation.

Epithelioid Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors

The clinical features of EMPNST are identical to those of the spindle cell form of this tumor, as described earlier.

EMPNSTs differ substantially from spindle cell nerve sheath sarcomas microscopically. The former neoplasms are composed solely of polyhedral cells that are arranged in cords, clusters, and sheets, often separated by myxoid or mucinous stromal material. Nuclei are vesicular with prominent nucleoli, and mitotic activity is brisk; cytoplasm is amphophilic, eosinophilic, or clear, and variable in quantity76,170,171 (Figs. 23-49 and 23-50). Interpretation of this relatively nondescript image is aided in some cases by an obvious association between the tumor and a large nerve. Nevertheless, it is further complicated in selected cases by the fact that EMPNSTs may show obvious melanin production, in likeness to melanotic neurilemmomas.

Figure 23-49 Epithelioid malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors of the skin, showing cords and clusters of atypical polygonal tumor cells in variably dense stroma. Rarely, these neoplasms may assume a “rhabdoid” appearance, with abundant eosinophilic glassy cytoplasm (lower right panel).

Figure 23-50 Metaplastic tissues in epithelioid malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors of the skin may include melanocytic elements (left) or osteochondroid components (right).

Pigment production in EMPNSTs may produce great difficulty in differential diagnosis with metastatic melanoma (particularly with its “myxoid” variant,172 or with clear cell sarcoma). This problem is only partially soluble with electron microscopy or immunohistology. The first of these studies shows the generic ultrastructural features of MPNST but also demonstrates premelanosomes in the pigmented elements. Immunohistologically, 75% of epithelioid MPNSTs are reactive for podoplanin173 (Fig. 23-51), which is lacking in melanomas. However, the remaining 25% of cases are problematic diagnostically.174

Figure 23-51 Immunoreactivity for podoplanin (with antibody D2-40; left) and CD57 (right) in epithelioid malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor of the skin. Neither of these markers is seen in epithelioid malignant melanoma.

Several other epithelioid cell sarcomas must likewise be considered as interpretative alternatives. These include epithelioid sarcoma, epithelioid leiomyosarcoma, and the “histiocytic” variant of malignant fibrous histiocytoma. None of these lesions is positive for podoplanin, and their other immunophenotypic properties usually allow for a clear separation from EMPNST.147

Malignant Granular Cell Tumors

Malignant cutaneous granular cell tumors are exceedingly uncommon, and fewer than 100 examples have been documented.114,175–179 They are seemingly restricted to adults, with a predominance in women. The majority have arisen on the proximal extremities or trunk as subcutaneous nodules or ill-defined plaques.

Recurrence after adequate surgical excision is the usual indicator that a granular cell tumor of the skin has aggressive biologic potential. Metastases have been seen in more than 50% of reported cases, involving the regional lymph nodes, lungs, liver, bones, and brain. Mortality approximates 80%.114

The microscopic features of malignant cutaneous granular cell tumor are closely similar to those of its benign counterpart, as described earlier. However, presumptive histologic signs of malignancy in such lesions include broad zones of spontaneous necrosis, invasion of blood vessels, and brisk mitotic activity with atypical division figures. It is also likely that the gross size of the tumor plays a role in determining the biology of malignant cutaneous granular cell tumor. Tumors larger than 3 cm seem to be at principal risk for recurrence or metastasis, if they also demonstrate the previously mentioned atypical microscopic features.178 Althausen and associates have suggested that an infiltrative tumor margin also correlates with a risk of recurrence.179

The differential diagnosis of malignant cutaneous granular cell tumor of the skin includes other primary cutaneous neoplasms as well as metastatic tumors with a granular cell appearance. Leiomyosarcoma of the skin may have a predominantly granular cell phenotype, as may basal cell carcinoma, melanoma, or angiosarcoma.118–125 Likewise, selected examples of metastatic visceral adenocarcinoma can simulate the appearance of primary malignant cutaneous granular cell tumor of the skin.180

Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Toker first described MCC in 1972. He designated the tumor “trabecular carcinoma of the skin” because of the histologic configuration he observed among the five cases that composed his original study. At the time, he believed trabecular carcinoma to be a sweat gland tumor,181 but subsequent ultrastructural and immunohistochemical studies revealed the presence of neurosecretory granules in tumor cells, indicating neuroendocrine derivation. The Merkel cell, which functions as a mechanoreceptor, was proposed as the possible cell of origin and is still considered a likely candidate, although no definite proof of Merkel cell derivation has been documented.182 Additional investigators, including Toker and coworkers, have since suggested that MCC derives from a primitive stem cell capable of epithelial or neuroendocrine differentiation.183,184 Other alternative designations for this entity have been neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin,185 primary small cell carcinoma of the skin,186 APUDoma,187 extrapulmonary carcinoma of the skin,188 primary neuroepithelial tumor of the skin,189 “murky cell” carcinoma,190 and merkeloma.189

MCC classically presents as a rapidly growing, painless, nonulcerated, red to violaceous nodule or plaque on the sun-exposed skin of elderly Caucasians.189 The reported age range has been from 7 to 97 years, the majority of patients being older than 65.191 The male-to-female ratio has varied among studies, but it was 1.6 : 1 in one series.192 The most frequently reported sites have been the head and neck, extremities, and trunk.193 Most tumors are approximately 2 to 4 cm in diameter,193 although those of the head and neck tend to be smaller.194 The correct clinical diagnosis is rarely made, because these lesions can resemble many other tumors. Because some of these skin tumors are associated with prolonged ultraviolet (UV) light exposure, sunlight has been suspected to play a role in the development of MCC.193 In this connection, Van Gele and coworkers reported that one MCC cell line showed a UVB-induced C to T mutation, thereby suggesting that sun exposure may indeed participate in the pathogenesis of this tumor.195 However, this does not provide a completely satisfactory explanation, because MCC has clearly been reported in non–sun-exposed sites. There is an increased incidence of MCC in immunosuppressed patients, such as those with human immunodeficiency virus infection, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, or rheumatoid arthritis, and especially in organ transplant recipients.196–199 Penn and First reported on a series of 52 organ transplant patients who later developed MCC. Tumors developed from 5 to 286 months after transplantation. The anatomic distribution was similar to that of typical MCC, but tumors tended to arise at a younger age, with a mean of 53 years. Twenty-nine percent of their patients were younger than 50 years of age.197 In recent years, it has been learned that most MCCs, in this country as well as other locations, are associated with what is now called the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV), which is integrated into the genome of this tumor.200 The virus can be detected in formalin-fixed tissues using PCR technology, but it has not been found in visceral high-grade neuroendocrine tumors from a variety of anatomic sites.201 The prevalence of this virus is high in immunosuppressed patients and may explain, in part, the increased incidence of MCC in these individuals.202 Treatments for MCC generally include surgical excision and/or radiation therapy.

Microscopic Findings

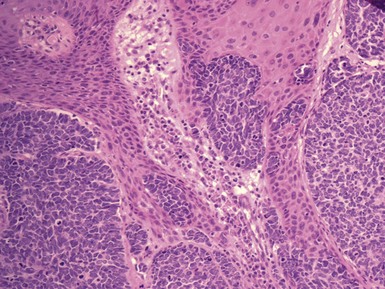

MCC usually has a gray-to-white cut surface on gross examination.203 Microscopically, the majority of tumors arise within the dermis, but they may extend into the subcutaneous tissue.189 Although the epidermis is usually not involved, epidermotropism and, rarely, lesions confined to the epidermis have been reported (Fig. 23-52).204–207 In one series, 6 of 36 cases showed definite epidermal involvement, with an additional case showing aggregates of tumor cells at the dermal-epidermal junction.192 Gould and coworkers have described three histopathologic patterns. These include a trabecular type, with connective tissue separating interconnecting cellular trabeculae (Fig. 23-53); an intermediate cell type (most common) consisting of solid nests (Fig. 23-54), with trabeculae at the periphery; and a small-cell type (least common) consisting of sheets of small cells, with a diffusely infiltrative pattern.208

The cells in MCC possess scant cytoplasm and round to oval nuclei that usually measure 14 to 20 µ in diameter and show finely dispersed chromatin.203 Molding of cells, which has been described as a “ball-in-mitt” arrangement, is frequently noted.189 Aggregates of giant tumor cells can sometimes be identified; except for the size and irregular contours of their nuclei, these cells closely resemble the more traditional cells of MCC in other respects, including chromatin pattern, tendency toward molding of cells, and staining reactions (Fig. 23-55). Aggregates of tumor cells sometimes produce a pseudorosette appearance. Mitotic activity is frequently brisk. In the study by Silva and colleagues, 76% of tumors had four to nine mitoses per high-power field and 18% had greater than 10 mitoses per high-power field, whereas fewer than 5% of tumors had three mitoses or less per high-power field.203 An infiltrating margin is most commonly observed,203 and a lymphocytic infiltrate may surround and/or infiltrate the tumor cells.192,199

Figure 23-55 Merkel cell carcinoma. There is an aggregate of giant tumor cells. Despite their size, they have nuclei with chromatin patterns similar to those of conventional Merkel cell carcinoma, and the staining reactions are the same.

Other reported histologic variants include squamous, eccrine, leiomyomatous, or melanocytic differentiation.208–210 Some authors believe that these divergent types of differentiation lend support to the theory of a pluripotential stem cell origin for MCC. Toker and associates originally described the link with sweat gland differentiation. However, clear-cut eccrine differentiation is not commonly observed; a much more common finding is that of “entrapment” of sweat ducts or glands by tumor cells. It is often difficult to identify unequivocal vascular or lymphatic invasion, both because of the density of tumor infiltration and because of a potentially misleading retraction phenomenon that often surrounds groups of tumor cells.

Other malignancies have also been reported within, overlying, or adjacent to lesions of MCC, including actinic keratosis, Bowen disease and invasive squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, and sweat gland tumors (Fig. 23-56).193

Figure 23-56 Merkel cell carcinoma. This tumor has arisen adjacent to squamous cell carcinoma in situ.

Using immunohistochemical techniques, MCC commonly shows positivity for neuron-specific enolase and EMA.

Staining for chromogranin A, a neurosecretory granule protein, has shown widely ranging results in previous studies, but there appears to be some positivity in about 50% of cases. Stains for neurofilament and synaptophysin seem to produce similar results.189,193 Some MCCs are reported to show positive reactions for vasoactive intestinal peptide, calcitonin, and somatostatin. Less frequently, reactivity may be found for leucine enkephalin, gastrin, adrenocorticotropic hormone, met-enkephalin, bombesin, pancreatic polypeptide, and substance P.193 Numerous studies of keratin reactivity in MCC have been performed. CK20 staining shows a characteristic punctate perinuclear deposition pattern (Fig. 23-57). The location and configuration of this staining reaction correspond to those of the perinuclear filament whorls observed by electron microscopy.211 Frequently, positive staining with antibodies to Cam 5.2 and AE1/AE3 keratin cocktail is also observed.212 These often also produce dotlike perinuclear staining, although a more diffuse cytoplasmic positivity is sometimes noted when staining with keratin cocktail. CK7 positivity has also been described.213 Thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) is a homeodomain transcription factor that is expressed in the thyroid gland, lung, and diencephalon. Most small-cell carcinomas of the lung stain positively for this antigen, whereas MCCs are uniformly negative.214,215

Differential Diagnosis

The histologic differential diagnosis includes melanoma, lymphoma, cutaneous small-cell epithelial tumors (including small-cell squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, or sweat gland carcinoma), peripheral neuroepithelioma (PNET), and particularly metastatic small-cell (neuroendocrine) carcinoma. In addition to the small-cell type that all of these tumors can potentially share, nodular aggregates of cells in MCC can resemble the nests of malignant melanoma. This is particularly the case when groups of tumor cells are identified near the dermal-epidermal junction or within the epidermis. The clefting artifact sometimes observed around tumor islands can also produce a superficial resemblance to basal cell carcinoma. Cases showing evidence for duct formation might suggest sweat gland carcinoma, while the presence of pseudorosettes raises the possibility of peripheral neuroepithelioma.

Nuclear details are of considerable importance in making a diagnosis of MCC. The nuclei of these tumors typically display rounded contours and finely dispersed chromatin. In well-performed histologic sections, these nuclear features provide particularly strong evidence against melanoma, lymphoma, or cutaneous small-cell epithelial tumors. Molding of tumor cells and evidence for eccrine or squamous differentiation, if present, further argue against malignant melanoma, as does the absence of junctional or intraepidermal cellular proliferation lateral to the main tumor mass. Broad connections to the epidermis generally favor squamous cell carcinoma, whereas well-developed peripheral palisading of tumor islands is a characteristic of basal cell carcinomas not seen in MCC. Unlike MCC, PNETs may contain true Homer Wright rosettes with central neurofibrillary material. Secondary small-cell carcinomas involving the skin frequently show the “Azzopardi phenomenon”: basophilic encrustations of blood vessels within the tumor that presumably represent degenerated nuclear material in a rapidly replicating neoplasm.214 This is generally not observed in primary cutaneous MCC, although it has been reported.216 Electron microscopy can also provide useful diagnostic information. The presence of neurosecretory granules excludes melanoma, lymphoma, and cutaneous epithelial tumors, including sweat gland carcinomas. Perinuclear filament whorls are not seen in sweat gland tumors, and their presence also favors primary cutaneous MCC over metastatic small cell carcinoma.217,218

Fortunately, the advent of immunohistochemistry has permitted clear distinction of MCC in most instances. Generally, the punctate keratin staining and positivity for neuroendocrine markers distinguish MCC from malignant melanoma, lymphoma, or cutaneous small-cell epithelial tumors. Malignant melanoma is usually positive for S-100 and vimentin; this has rarely been reported in MCC.189,219 Additional testing using HMB-45 and tyrosinase may also help in distinguishing these two entities.220 Leukocyte common antigen (LCA) is positive in lymphomas, whereas it is negative in MCC.193,221 The other epithelial and neural markers commonly seen in MCC are negative in lymphoma.221,222 It should be noted that basaloid eccrine carcinomas sometimes express neuron-specific enolase, a potential diagnostic pitfall if other keratin or neuroendocrine markers are negative or equivocal.218 Despite a probable histogenetic relationship between MCC and PNET, the latter tumor can usually be distinguished because, unlike MCC, it is negative for keratin (including CK20), negative for EMA, and positive for vimentin.223 A hallmark of PNET is its positivity for CD99, which unfortunately is also positive in about 50% of MCC cases.

Distinction between MCC and metastatic small-cell (neuroendocrine) carcinomas can be more problematic. In contrast to MCC, metastatic small-cell carcinomas usually express carcinoembryonic antigen, and they also are more likely to express the neuropeptides bombesin and leucine encephalin.224 Metastatic small-cell carcinomas do show pancytokeratin positivity but are infrequently positive for CK20.225 Other distinguishing immunohistochemical findings include the negative staining for TTF-1 in MCC214,215 and the lack of staining for neurofilament in metastatic small-cell carcinoma.225

Primary Cutaneous Meningioma

Primary meningioma of the skin is characteristically encountered in the scalp in young adults. It manifests as an unremarkable nodular 0.5- to 2-cm mass, and affected patients typically do not have a phakomatosis.226,227

Microscopically, one sees nests, cords, or sheets of ovoid, polygonal, and fusiform cells in the corium, which may form concentric arrays (Fig. 23-58). Cell borders are variably distinct, and nuclei are round to oval with dispersed chromatin and occasional intranuclear pseudoinclusions of cytoplasm (Fig. 23-59). Cytoplasm is usually amphophilic but may be lipidized or clear. The overall growth pattern of the lesion is commonly permeative, often extending deeply into the subcutis and even into deeper soft tissue; however, the epidermis is usually uninvolved. Psammomatous calcifications are focally seen in approximately 50% of cases (Fig. 23-60).227

Figure 23-58 Primary cutaneous meningioma of the scalp is shown in a magnetic resonance imaging scan (top right panel). Histologically, it is represented by a solid mass of epithelioid and fusiform cells in the deep dermis and subcutis (left and bottom right panels) with a vaguely organoid internal architecture.

Figure 23-59 Another microscopic characteristic of meningioma is its tendency to form vague (left) or well-defined cellular “whorls.”

Figure 23-60 Small psammomatous microcalcifications at the bottom of the figure are often present in cutaneous meningiomas.

In likeness to meningiomas of the neuraxis, Rushing and coworkers228 found that primary cutaneous meningiomas demonstrated a spectrum of histologic incarnations. These included meningothelial-predominant tumors that comprised mainly polyhedral cells, “transitional” lesions with an admixture of spindle cells, “fibrous” meningiomas that were principally fusiform cell tumors, “metaplastic” lesions containing cartilage or bone, and “chordoid” or clear cell neoplasms. Furthermore, meningiomas of the skin potentially manifest all three histologic grades as defined by the World Health Organization, with grade III tumors representing malignant tumors (“anaplastic” meningiomas). With increasing grade, one observes more nuclear pleomorphism, mitotic activity, increasing nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios, a tendency for sheetlike growth, prominent nucleoli, and the appearance of intratumoral geographic necrosis.228

Depending on its specific histologic appearance, a cutaneous meningioma may be confused with an appendageal carcinoma of the skin, an epithelioid cell or spindle cell sarcoma, a PNST (particularly perineurioma), or even an amelanotic melanoma. Electron microscopic studies are still valuable in this differential diagnostic context, because meningioma has a singular appearance. It features extensively interdigitated cell membranes that are linked by well-formed tripartite desmosomes.227,228 None of the other interpretative alternatives conforms to that ultrastructural description. Immunohistology is less helpful, because meningiomas have a relatively heterogeneous staining profile. They typically are labeled for EMA and vimentin, but may, in some instances, also express keratin, S-100 protein, p63, claudin-1, podoplanin, GLUT-1, and collagen type IV.229–235 That capability produces substantial overlap with the immunophenotypes of several other neoplasms.

Subcutaneous Ependymoma

The coccygeal medullary vestige is an ependymally lined cavity at the caudal end of the vertebral column, thought to represent a remnant of the neural tube. It is present in 10% to 15% of otherwise normal individuals.236 From that structure, a glial neoplasm situated in the precoccygeal soft tissue or retrococcygeal subcutis is thought to potentially arise: namely, extraspinal ependymoma. The first example of this lesion was documented by Mallory in 1902,237 and approximately 100 cases have been reported since then.236,238,239 Most sacral extraspinal ependymomas produce no complaints other than a mass, and they are usually thought to represent pilonidal cysts clinically, occurring in children or young adults.

Microscopically, virtually all extraspinal ependymomas of the sacral subcutis are myxopapillary ependymomas.236 The salient histologic feature of such neoplasms is the presence of micropapillary configurations comprising polygonal cells (Fig. 23-61). They typically have rounded nuclei with delicate, open chromatin and a moderate amount of amphophilic cytoplasm. The cores of the papillae contain hyalinized blood vessels that are surrounded by a variable amount of mucoid matrix (Fig. 23-62). Mitotic activity is limited in scope or altogether absent. Myxopapillary ependymomas usually have sharply defined borders, but they may enclose nearby nerve roots. A proportion of these lesions is surrounded by an attenuated capsule.238,239

Figure 23-61 Subcutaneous sacrococcygeal myxopapillary ependymoma is shown here in a magnetic resonance imaging study after administration of contrast dye (left panel). Histologically, the tumor is made up of aggregates of bluntly fusiform cells that are arranged in micropapillae, separated by myxoid stroma (right panels).

Figure 23-62 The vascular cores in the papillary structures of myxopapillary ependymoma are usually hyalinized, as shown here (left; top right). This tumor is immunoreactive for glial fibrillary acidic protein (bottom right).

Immunoreactivity is typically present in sacral subcutaneous extraspinal ependymoma for glial fibrillary acidic protein, S-100 protein, and vimentin. On the other hand, no labeling is seen for keratins, EMA, or podoplanin.236,238 That constellation of findings allows one to exclude the differential diagnostic possibilities of adnexal carcinoma, chordoma, and extraskeletal chondrosarcoma.

Pseudotumors of the Skin Related to the Nervous System

Rudimentary Meningocele (Meningotheliomatous Hamartoma)

In 1974, Lopez and colleagues reviewed the clinicopathologic attributes of several non-neoplastic meningothelial cutaneous lesions and adopted the term “acoelic meningeal hamartoma” to describe them.226 That rubric implied that the masses in question had no connection to the central nervous system or its coverings, and it also indicated that they were thought to be non-neoplastic. The latter issues were reviewed by Sibley and Cooper240 in 1989, yielding a similar interpretation. Those authors coined the term “rudimentary meningoceles,” signifying the premise that the lesions were formed by non-neoplastic rests of the meninges that had become entrapped within the integument early in life. This same construction was espoused by Suster and Rosai,241 except that the alternative designation “meningotheliomatous hamartoma” was chosen.

Rudimentary meningoceles show reproducible clinical features. Unlike true meningoceles, which are typically noted in the neonatal period and show radiographic evidence of continuity with the cerebral investments, rudimentary meningoceles manifest themselves later in childhood as nodular dermal-based lesions, usually in the skin of the posterior scalp or neck (Fig. 23-63), sometimes in association with annular alopecia or an abnormal tuft of hair.242–246 There may or may not be subjacent defects in cranial suture lines (Fig. 23-64), but no underlying nervous system abnormalities are evident.240,241,247 These same features distinguish the rudimentary meningocele from secondary cutaneous meningiomas. The latter are seen typically in the frontal or superior scalp in middle-aged or elderly patients, and the lesions derive from direct cutaneous extension by true neoplasms of the meninges.226

Figure 23-63 Clinical photograph of a rudimentary meningocele in the skin of the lower neck in a child. The lesion is exophytic and fluctuant.

Figure 23-64 Computed tomogram of the head, showing the presence of a rudimentary meningocele in the occipital soft tissue. No underlying abnormalities in the cranial bones are apparent.

The microscopic appearance of rudimentary meningocele is potentially deceptive, with a deep dermal and subcutaneous proliferation of polygonal cells with oval nuclei, dispersed chromatin, and a moderate amount of amphophilic cytoplasm. Rudimentary meningoceles are arranged in a dyshesive, “dissecting,” permeative pattern in the supporting connective tissue, but are, nonetheless, relatively circumscribed on scanning microscopy (Figs. 23-65 and 23-66). Like meningothelial cells in general, the proliferating elements of rudimentary meningoceles are immunoreactive for EMA and vimentin.240,241,247

Figure 23-65 Rudimentary meningocele, represented by a racemose proliferation of bluntly spindled cells mantling pseudovascular spaces in the deep dermis and subcutis.

Figure 23-66 Cytologically bland fusiform cells dissect through the dermal collagen and form pseudovascular structures in this rudimentary meningocele (left). They are immunoreactive for epithelial membrane antigen (right).

The intercellular spaces formed in rudimentary meningoceles and the overall image produced are reminiscent of the features of angiosarcomas or atypical hemangiomas.241 Nevertheless, there are no erythrocytes in the first-named of these lesions, and serial sections may demonstrate the presence of small psammomatoid calcifications. The latter findings are not expected in vascular tumors; this is also true of EMA immunoreactivity. Another differential diagnostic consideration is the neoplasm known as “giant cell fibroblastoma,”248 which similarly features the presence of intratumoral pseudovascular channels. However, that lesion is a juvenile form of dermatofibrosarcoma that is found preferentially on the extremities of adolescents, and it has a second constituent growth pattern, which is composed of a more solid fibroblastic proliferation. Giant cell fibroblastoma is negative for EMA and reactive for CD34.247

Cutaneous Glial Heterotopia (“Nasal Glioma”)

Another malformation that is pathogenetically similar to rudimentary meningocele is cutaneous glial heterotopia (CGH), also known inaccurately as “nasal glioma.”249–257 This lesion is seen in children; in “pure” form, it represents the growth of cerebral matter that has become detached completely from the subjacent brain during development. Other clinically similar masses are, instead, accompanied by patent subjacent meningeal tracts through the skull that are definable radiographically; these should be regarded technically as encephaloceles rather than heterotopias.254 Because gross examination is incapable of distinguishing CGH from an encephalocele, and casual excision of the latter lesion carries a major risk of iatrogenic meningitis, all patients with these abnormalities should receive a thorough neuroradiologic evaluation.254

Both CGH and encephaloceles characteristically present in the skin of the nasal bridge as single, asymptomatic, firm, pink, tan, or violaceous nodules (Fig. 23-67). Extension of the masses into the nasal cavity is seen in a minority of cases.251,253

Figure 23-67 Heterotopic glial tissue in the skin over the bridge of the nose (“nasal glioma”), represented by a multinodular cutaneous lesion in an infant.

The microscopic attributes of CGH are responsible for its having been assigned the erroneous designation of “glioma.” A proliferation of astrocytes—with or without a minor population of oligodendroglia or the formation of plump eosinophilic “Rosenthal” fibers—is observed histologically, with subdivision by a delicate fibrovascular stroma (Figs. 23-68 and 23-69). One sees fibrillary background neuropil, and scattered ganglion cells are apparent in a minority of cases. No “secondary” features of true gliomas, such as perivascular hypercellularity or submeningeal astrocytic proliferation, are evident in CGH. Mitoses and necrosis are absent uniformly.250–254,257

Figure 23-68 Fascicles of bland stellate cells are punctuated by prominent stromal blood vessels in this example of cutaneous glial heterotopia.

Figure 23-69 The mixture of glial and neuronal elements in glial heterotopia is well seen in the left panel of this photograph. The glial components are immunoreactive for glial fibrillary acidic protein (right).

If a demonstration of the non-neoplastic nature of CGH is desired, the proliferating glial cells can be labeled for glial fibrillary acidic protein immunohistologically, and the neuropil is reactive for neurofilament protein. Ganglion cells are recognizable with stains for synaptophysin and MAP-2. This pattern of conjoint immunoreactivity is incompatible with the diagnosis of a true glioma.255

Neuromuscular Hamartoma

Neuromuscular hamartoma (NMH), or “benign triton tumor,” was probably first described by Orlandi in 1895.258 This lesion is typically associated with large nerves in deep soft tissue locations,259–264 but, occasionally, localization in the skin may be encountered as well. Indeed, O’Connell and Rosenberg documented two examples of that eventuality in an infant.265

Histologically, NMH shows an intimate admixture of striated muscle fascicles with tissue, resembling that seen in post-traumatic neuroma (Fig. 23-70). No nuclear pleomorphism or atypia is present, and the peripheral aspects of the lesion are “fuzzy” or indistinct but still circumscribed on scanning microscopy. Immunostains demonstrate a clearly bifid cell population, with one labeling for S-100 protein, CD56, and CD57, and the other reacting for muscle-specific actin, desmin, and myoglobin.265 Van Dorpe and colleagues266 described a case in which a smooth muscle component was present as well in a deep-seated NMH.

Figure 23-70 Neuromuscular hamartoma of the dermis and subcutis is composed of a random admixture of benign Schwannian and striated muscular tissues (left; top right). The myogenous elements are labeled for desmin (bottom right).

Differential diagnosis mainly centers on the distinction of NMH from malignant triton tumor (MPNST with divergent differentiation) and “ectomesenchymoma” (PNET with divergent neuronal and rhabdomyoblastic differentiation.267 Both of the latter lesions exhibit obvious cytologic anaplasia, unlike NMH.

Patterns of Growth in Cutaneous Adipocytic Proliferations

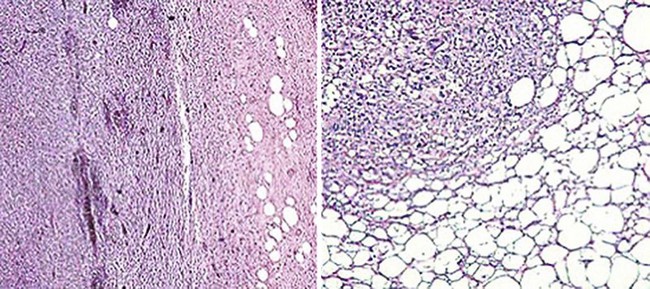

Cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions with an adipocytic lineage basically have only two growth patterns: circumscribed and infiltrative. However, they can be further classified by attention to selected other histologic findings, as presented in Figure 23-71. Exemplary images of diagnostic microscopic features in this group of lesions are illustrated in Figures 23-72 to 23-81.

Figure 23-71 Potential microscopic growth patterns in cutaneous proliferations composed of fatty elements.

Figure 23-77 Ordinary superficial lipoma of the temple, represented clinically by a compressible soft nodule in the subcutis.

Figure 23-79 Photomicrographs of spindle cell lipoma, showing an admixture of nondescript bland spindle cells, myxoid stroma, and mature lipocytes.

Figure 23-80 Occasional examples of spindle cell lipoma may be greatly dominated by their nonadipocytic components, leading to confusion with soft tissue neoplasms of other lineages.

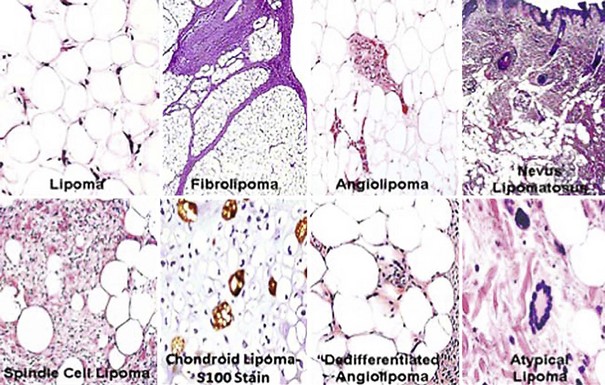

Lipoma Variants

Lipomas are almost ubiquitous in adults. Nevertheless, when they arise in cosmetically unacceptable locations or in patients who are anxious about “growths,” they are excised. Macroscopically, lipomas are compressible, mobile, irregularly nodular lesions that may be seen in the deep soft tissues or the subcutis (see Fig. 23-77); they can attain an impressive size. The fatty nature of such tumors on cut section is usually obvious.

Particular clinical variants of lipoma with pertinence to the superficial soft tissue include the “spindle cell,”268–276 “atypical/pleomorphic,”269,270,272,277 “sclerotic,”278,279 “fibrohistiocytic,”280,281 “glandular,”282,283 “chondroid,”284–287 and vascular (angiolipomatous)288–290 subtypes. The first of these is most often seen in elderly patients on the upper trunk, with males predominating. The base of the neck and the interscapular region are common sites of origin for spindle cell lipomas, and they may be multiple or familial.273,291 Those lesions may be firmer and more fixed to surrounding tissue than usual lipomas. Pleomorphic/atypical lipomas likewise may have a dense consistency, and they are found on the extremities or the head and neck.292 Angiolipomas have a broader anatomic distribution but are distinguished from other lipoma variants by their painful nature when traumatized or palpated.289 Sclerotic, glandular, chondroid, and fibrohistiocytic lipomas are purely histologically defined subtypes.

Uncommonly, patients with lipomas manifest the syndrome of familial lipomatosis, wherein hundreds of fatty lesions appear throughout life in a multitude of topographic sites.293,294 Lipomas also may be components of Gardner syndrome, together with familial adenomatous polyposis of the colon.294

In their usual banal form, lipomas represent localized overgrowths of mature adipocytes that are bounded by thin fibrous capsules (see Fig. 23-78). Internal stroma is delicate and inconspicuous.294,295 Simple entrapment of adnexal epithelial structures (especially eccrine glands) in superficial lipomas yields the image of so-called “adenolipoma” (glandular lipoma).282,283

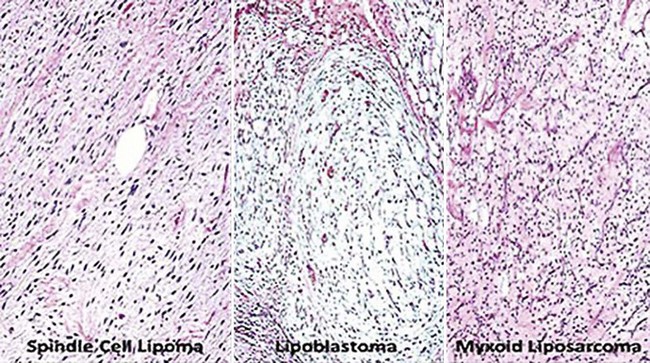

Spindle cell lipoma (SCL) is a triphasic neoplasm in which lobules of mature fat cells are interposed with zones of bland spindle cell growth and other areas of myxoid stromal change268,291 (see Figs. 23-79 and 23-80). In some cases, the latter two components may be dominant, leading to diagnostic consideration of a neural or a fibroblastic proliferation296; in rare examples, metaplastic osteoid or cartilage is seen in such tumors, or a prominent vascular stroma may lead to diagnostic consideration of an endothelial lesion (“pseudoangiomatous” SCL).297 French and associates270 have described a purely dermal variant of SCL, which differs from subcutaneous lesions in showing a wider anatomic distribution and a lack of histologic circumscription. Kelley and coworkers documented another form containing collagen rosettes.298

The differential diagnosis of SCL also includes mammary-type myofibroblastoma.299 In fact, that tumor is histologically indistinguishable from SCL, but it shows immunoreactivity for myogenous markers such as desmin and muscle-specific actin, which SCL lacks. Both tumors express CD34300 (see Fig. 23-81), and it is probable that they represent two points in a neoplastic continuum rather than distinct and separate pathologic entities. Another lesion that resembles SCL is the fibrous hamartoma of infancy. However, those two proliferations occur in mutually exclusive patient populations (young children vs. middle-aged or elderly adults). Moreover, CD34-positivity in SCL distinguishes it from fibrous hamartoma.300

Pleomorphic or “atypical” lipomas differ from ordinary lipomas because they contain “floret” cells, with or without lipoblasts269,270,277,292 (Fig. 23-82). The floret cells are multinucleated and atypical but cytologically bland elements with “smudgy” chromatin that are interspersed throughout the background population of adipocytic elements. Lipoblasts in these tumors may have either a “signet-ring cell” or “mulberry” configuration. A modest increase in stromal fibrous tissue also may be apparent in such masses, recalling the image of well-differentiated sclerosing liposarcomas of deep soft tissue. A limited amount of myxoid stroma also may be present. The overall configuration of the mass—including sharp circumscription, a superficial location, and a lack of mitotic activity—is diagnostic.292 The authors do not make a distinction between “atypical” and “pleomorphic” lipoma in superficial soft tissue sites, because they believe that difference to be arbitrary and artificial. Conceptually, the morphotypic patterns just described for this family of lesions probably do represent special variants of very well-differentiated liposarcomas. However, such lesions lack aggressive behavior because they are so superficial, and the subcutis may be a special immunologic compartment that restricts neoplastic growth.

Figure 23-82 Atypical pleomorphic lipoma of the subcutis, represented by a circumscribed mass (top left) containing scattered multinucleated “floret” tumor cells with hyperchromatic nuclei.