ONE

THE TEMPEST

The Conundrum of Man

AT THE LUTHER LUCKETT CORRECTIONAL COMPLEX in Kentucky, inmates have the opportunity to join a Shakespeare production troupe (all male) that will rehearse and perform one of Shakespeare’s plays, directed by a gifted Shakespearean actor, Curt Tofteland, who has been going to the prison since 1995. Some plays that have been produced by this group (or a subset of them; some are repeat performers, some are new) include Othello, Titus Andronicus, and Hamlet—all chosen in part because they engage the themes of crime, guilt, and repentance. A production of The Tempest, the culmination of that series, was the inspiration for a documentary, Shakespeare Behind Bars, in 2004. The film, which describes and shows scenes from this production, was singled out for mention at the Sundance Film Festival.1

The director, Hank Rogerson, presents rehearsal scenes and interviews with the actors. His technique is striking and effective: first you see them perform; then, gradually, you learn something about their crimes, and why they are in prison—many of them for life. These personal stories are given to us bit by bit, in small pieces of information, so that the actors we have grown to like and even to admire are only slowly revealed to have had other, in some cases startlingly violent, lives. What makes these stories so gripping is in part the relevance of the personal to the performative: each inmate discovers in his dramatic character some deep pertinence to his personal life, and even sometimes to his crime.

What is striking, too, is how different this version of the play is from those one might see in a modern theater or read about in contemporary Shakespeare criticism. Take the issue of race. Although several of the inmates are black, none of them is cast as Caliban. The Caliban of this production is a large white man with blond hair, who performs masterfully, shouting out curses, developing a distinctive crawl along the floor. Race and gender are not major factors in this performance, at least in any stereotypical way. Instead, the play is manifestly, to its actors, about redemption. At the very end of the play, the final couplet of Prospero’s epilogue, spoken to the audience, is,

As you from crimes would pardoned be,

Let your indulgence set me free.

Epilogue 19–20

And these lines seem to have a special, direct, and contemporary pertinence to both the audience and the actors.

Some inmates hope that acting in the Shakespeare play—a recreation favored by the prison administration—will get them closer to parole. Others feel that the process is itself redemptive and cleansing, as well as engaging and exciting. Better than mopping floors. Trinculo—the actor seen in the opening moments speaking Prospero’s speech—is a particularly affecting individual who acts as a recurring narrative presence throughout the documentary. At the end we see the performance, and find out what happened to the performers.

The film is effective both on its own, as an autonomous work of art, and also as a symptomatic and striking instance of the intersection between Shakespeare and modern culture. The play is not appropriated, trivialized, or merely thematized. It may or may not be “therapeutic.” But the important thing, for the actors, the camera, and the viewers, is that it is acted. It is performed and experienced as a piece of theater. Shakespeare’s “genius” is nowhere merely lionized. What we encounter, instead, is the contemporary relevance of Shakespeare as playwright—and the contemporary relevance of The Tempest.

THE TEMPEST ENGAGES THE QUESTION of modern culture in a number of different, direct, and overlapping ways. By “modern culture” here we might mean things as various, or as congruent, as colonialism, race relations, master-slave dynamics, psychoanalysis, cognition and the structure of the mind, “science” and “art” as (post) magical practices, feminism, geopolitics, environmentalism, governance, and the rationale for what we now call “general education.” All presented in a marvelously compact package, a brilliantly conceived, tightly structured play that takes place in a short time, in a single space: an enchanted island located either in the New World, near Bermuda, or in the Old, somewhere between Naples and Tunis, or in the imagination.

In its dramatic form The Tempest is a comedy that recuperates what could have been a tragedy. It belongs as well to the genre of the revenge play, a popular mode in the period—but one that in its more usual form ends with death, and repetition: the ghost returns, a past wrong is recalled and righted. In this case the repetition comes at the beginning, as the very engine of transformation (storm, wreck, loss, plot, discovery). Events of twelve years ago are retold, recalled, and revisited, as the magical storm wrought by Prospero brings to the island the very same people who were the cause of his usurpation and exile. So it should come as no surprise to find that the internal mechanism of the play—repetition with a difference—becomes, as well, the mechanism of its history, or histories (in the plural) in modern culture.

There are several “histories” here, all interesting, all intertwined:

• the history of the play’s performances

• the history of its adaptations

• political and cultural history (exploration and settlement; colonial and postcolonial)

• the history of literary criticism (romanticism, liberal humanism, new historicism, cultural materialism, psychoanalysis, postcoloniality)

• the history of “Shakespeare”—that is, fantasies about the author, in this case focusing on the persistent fantasy that the play is his “farewell to the stage”

• or the history of the sciences of “man”—theories of the self, the subject, the unconscious, and evolution

To further explain this last category: the play has been read and staged in recent years with a special attention to colonialism (both early modern and recent) and to race. But it also has powerful historical and conceptual resonances with the master narratives of the last century, the grand narratives generated by Darwin, Freud, and Marx, the narratives through which (and in reaction to which) “modernity” and “postmodernity” have come to position themselves. Jean-François Lyotard defines postmodernism as a skepticism or “incredulity” toward grand narratives—the refusal to believe that there are metastories about man and “progress” and, indeed, “liberation.”2 And this tension—between belief in a grand narrative and skepticism or distrust—could be said to animate the tensions both within Shakespeare’s play and between the play and its various interpreters or appropriators. The play itself has been repeatedly “colonized,” used as a staging area for arguments about the transcendence of poetry, about Shakespeare the Man, about cultural politics, and about mastery and subjugation.

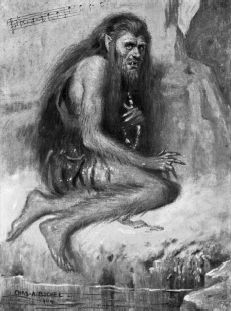

GRAND NARRATIVES CREATE trajectories for thinking—and for categories of thought. Darwin mapped the “descent of man” and the evolution of species—and The Tempest can be seen (and was read, a hundred years ago) as a kind of ethnography or natural history of evolutionary life stages, with Caliban related to beasts, fish, and animals, and Ariel to airy spirits. Many productions of the play at the turn of the last century featured a Caliban who was, to cite the title of a book published in 1873, Caliban: The Missing Link.3 Caliban attempts to rape Miranda and people the isle with Calibans. (We might say that the play in this period was evolutionary psychology, though the term had not yet been invented.) But the nineteenth century and the early twentieth century regarded Caliban as a figure of pathos, aspiring to a higher condition (“I’ll be wise hereafter, and seek for grace”). Percy MacKaye’s 1916 “community masque,” Caliban by the Yellow Sands, performed at New York’s Lewisohn Stadium, presented Prospero as guiding Caliban toward moral improvement: “Caliban seeking to learn the art of Prospero…the slow education of mankind through the influences of cooperative art.”4 This was the Darwin of his own time, the Darwin of the late nineteenth century and the early years of the twentieth.

Charles Buchel, Herbert Beerbohm Tree as Caliban

THE TWO THEORIES of human evolution, Darwin’s and Freud’s, are in a way natural counterparts. One tells the long story of the species; the other the short story of the individual. Both are “evolutionary”—they see a series of accidents, events, traumas, recuperations from trauma, beginnings over again: the history of “man.”

My suggestion for a keyword for The Tempest and its effect upon modern culture would, in fact, be this problematic word “man.”5 “Man” as a general substantive for all mankind raised a number of problems for the late twentieth century. Did it include “woman”? Did its use flatten out important cultural differences and histories? What about its older use to mean “servant” (my man—“’Ban, ’ban, Cacaliban / has a new master.—Get a new man!” [2.2.175-6])? “Man” can mean a human being of either sex, a male person, the human race or species. The debates about the use of the term, among anthropologists, linguists, literary critics, historians, and professional writers and thinkers, have in a way defined some of the most trenchant conversations about culture (and that equally contested term, “civilization”) for the last several decades. The wide range of meanings of “man” (mankind, man or spirit, man or beast, master and servant/slave, man and woman) and the tensions and injustices that arise in and around this set of definitions are themselves both prefigured, and encapsulated, in the dramatic action—and dramatis personae—of The Tempest.

That Shakespeare played with the meaning of this term is clear from a telling exchange in Hamlet, when Hamlet remarks to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, “Man delights not me—nor woman neither, though by your smiling you seem to say so.” This remark comes at the close of the very famous philosophical rumination about “What a piece of work is man,” a passage that ends with “And yet to me what is this quintessence of dust” (2.2.293–98). The shift from the one meaning of “man,” mankind, humanity, mortal existence, to the other meaning, male person, indeed male desiring person, is quick, shrewd, and definitive. The word “man” breaks apart into (at least) two meanings, one solemn, one erotic and comic.

In The Tempest, as we’ll see, this process of parsing, or dividing up, the various meanings of “man” becomes the topic of constant investigation. And, as we will also see, this contributes to the sense of the play’s current pertinence. In a way, all of the disciplines of knowledge that developed and were formalized from the end of the nineteenth century onward—anthropology, sociology, linguistics, psychology, all of what came to be known as “the sciences of man”—find their core narratives in The Tempest. The play is not only a parable of colonial appropriation and dispossession, but also, equally crucially, the story of art and science at a crossroads, of the aesthetic and the instrumental, the psychological, the biological, the creative imperatives and the death drive, all “bound up,” to use Ferdinand’s wondering phrase, “as in a dream” (1.2.490).

THE TEMPEST IN MODERN CULTURE has been the story of four characters, and of competing narratives, each bidding, at one time or another, to be the grand narrative of which this brilliant play is exemplar. The story of Prospero; the story of Miranda; the story of Ariel; and the story of Caliban. Each is intertwined with a certain view of history, and a certain view of man.

Other characters in the play have had their adherents and proponents. W. H. Auden thought Antonio was the strongest character in the play, because he is self-sufficient and content to be alone. Two female characters crucial to the narrative—the powerful witch Sycorax, Caliban’s mother (whom Prospero supplanted), and Claribel, the daughter of the King of Naples (married to an African and sent to Tunis)—are absent from the play’s dramatis personae, a fact that did not go unnoticed by feminist readers in the twentieth century. The poet H.D. identified herself with the “invisible, voiceless” Claribel, writing that “I only threw a shadow / On his page, / Yet I was his, / He spoke my name.”6

Prospero’s daughter, Miranda, the one woman we meet onstage, rebels against her father but, in doing so, falls in with his secret wish for her to marry Ferdinand. Her speech about the “brave new world / That hath such people in it”—describing, in glowing terms, the posse of usurpers and would-be murderers shipwrecked on the island—provided a title to the highly successful dystopian novel by Aldous Huxley.

But the cultural effect in particular of Ariel, Caliban, and Prospero, on realms of modernity from political manifestos to poetry, has been enormous. What seems to have happened is that artists, writers, psychologists, and the organizers of political movements have recognized Shakespeare’s Tempest as a prescient allegory of their own situation. In part because the play is, or seems to be, a fantasy—and because it is, or seems to be, both a story about mental life and a story about politics and culture—it offers a different kind of allegory than that represented by a tragedy or a history play.

We might begin with Prospero, not because he has always been regarded as the central figure, but precisely because in recent years he has not.

Prospero is a magician, like the magician who was the title character in Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus (1592). For Faustus’s initial goal, too, was the achievement of knowledge. In his opening soliloquy Faustus, in his study, reviews the extant practices of intellectual life—disputation, medicine, law, and divinity—and decides that magic is the strongest of them:

These metaphysics of magicians

And necromantic books are heavenly,

Lines, circles, signs, letters and characters—

Ay, these are those that Faustus most desires.

Oh, what a world of profit and delight,

Of power, of honour, of omnipotence

Is promised to the studious artisan!

All things that move between the quiet poles

Shall be at my command. Emperors and kings

Are but obeyed in their several provinces,

Nor can they raise the wind or rend the clouds;

But his dominion that exceeds in this

Stretcheth as far as doth the mind of man.

A sound magician is a mighty god.7

In the early modern period magic was a recognizable profession—science and magic were just at this time beginning to be distinguished from each other. To be interested in mathematics, astronomy, navigation, geography, cartography—and also in alchemy, divination, and occult philosophy—was not a contradiction in terms. In fact, this combination of skills, talents, and interests is the very combination that marked the famous magician John Dee (1527–1608), on whom Shakespeare may, indeed, have partly modeled the character of Prospero.

John Dee was noted for his mathematical treatises, his library of books (the largest in the country and one of the best in Europe at the time), and his conversations with angels and spirits, whom he sought out as a way of increasing knowledge, often with the help of a crystal glass. John Dee was also a friend of Tycho Brahe and knew the work of Nicolaus Copernicus. Again, science and “magic,” far from being at opposite poles, were often thought of as branches of the same kind of inquiry.8

And so they are again, in a way, today. “Genius” is often regarded as an aspect of scientific investigation and insight. Keys to the universe, whether through DNA, the splitting of the atom, relativity theory, or string theory, are envisaged as developing through science rather than through what we now call “the humanities”—literature, art, music, and philosophy. The split that developed in the seventeenth century, around the time of Francis Bacon and over the course of the succeeding century, between science and the humanities, and between science and “magic,” is in some ways being repaired.

A renewed centrality for Darwin and Darwinian theories—now once more, a hundred years later, to be found all over the press, the publishing world, and academia, whether from the side of sociobiology or biography and history—may lead to a recentering of Prospero as both a naturalist and a magician, an artist and a scientist. Biotechnology, genetic engineering, cloning, mutations, and hybrids have brought Darwin back to the center of cultural attention. And in this framework, Prospero as scientist, and Caliban as hybrid exemplar, are also center stage.

If Darwin mapped the species, Freud mapped the internal workings of the psyche, the evolution of the individual’s consciousness (and unconscious), through mental strategies like repression, displacement, condensation, and fantasy or wish fulfillment. And The Tempest can be—and has been—read as an allegory of the workings of the human mind, with the id (instinctual and desiring) represented by Caliban, kept in a cave when he is not needed for basic life functions: “we cannot miss him”—he carries wood and brings water. And the superego is represented by Ariel, who fulfills wishes and plans, and who also counsels the civilized qualities of mercy over revenge and retribution: “If you now beheld them,” Ariel tells Prospero about the distracted and imprisoned courtiers, “your affections / Would become tender.”

PROSPERO Dost thou think so, spirit?

ARIEL Mine would, sir, were I human.

5.1.19–20

Prospero is struck, as we might be, that a human being is taught something about basic humanity by a spirit, and concludes that “The rarer action is / In virtue than in vengeance” (5.1.27–28).

One of the best popular culture explorations of the role of the unconscious (and of something explicitly called the id) in The Tempest is the film adaptation from 1956, Forbidden Planet, which introduced Robby the Robot as the Ariel figure. Dr. Edward Morbius, a philologist and the film’s Prospero, discovers that the ultimate enemy to the planet Altair is his own unconscious—the monster that threatens the planet comes from his own id (“This thing of darkness I acknowledge mine” [5.1.278–9]). Meanwhile his daughter Altaira has fallen in love with the commander of the United Planets Cruiser. Morbius dies, Altaira prepares to return to Earth with the crew. (More recent pop culture spinoffs would include all the “desert island” television shows, from Gilligan’s Island to Lost, as well as a film like Cast Away [2000], in which the Ariel character is a volleyball named “Wilson.”)

But in the middle of the twentieth century Prospero was clearly associated in many minds with the humanities. In criticism he was regularly described as a “playwright”—the creator, onstage, of a play within a play. When the play was read as an art fable, he was the meta-artist, the artist who represented Shakespeare the Playwright.

In the 1950s and ’60s, in fact, The Tempest was many an English professor’s favorite play. It was, after all, a play about a man who preferred reading books to wielding political power. Here is how Prospero describes himself to his daughter Miranda (and to the audience) at the beginning of the play:

—being so reputed

In dignity, and for the liberal arts

Without a parallel—those being all my study,

The government I cast upon my brother,

And to my state grew stranger, being transported

And rapt in secret studies.

1.2.72–77

I, thus neglecting worldly ends, all dedicated

To closeness and the bettering of my mind.

1.2.89–90

Prospero, by this “neglect” of worldly things and focus on his scholarship, enabled his brother, Antonio, to “believe / He was indeed the Duke,” and to make a deal with the King of Naples, Alonso, to remove Prospero and his daughter, Miranda, both from the dukedom and from Milan altogether, by placing them in a leaky boat and setting them out to sea.

But the good old councillor Gonzalo (“a noble Neapolitan”) helped them, furnishing the boat with “rich garments, linens, stuffs and necessaries,” all of which they have been using, and wearing, on the island from that time twelve years ago to the present. Also, most centrally,

Knowing I loved my books, he furnished me

From mine own library with volumes that

I prize above my dukedom.

1.2.167–69

Notice that he still prizes his books above his dukedom, his political place in the world. It’s that preference, that choice, that led to his usurpation and exile, his loss of power in Europe.

In the mid-twentieth century this removal from the world, this choice of scholarship rather than political engagement (and what would have looked, presumably, like humanistic scholarship—“books”—rather than laboratory science for human betterment [or for the arms race]), was, for some people, a choice that seemed personal, self-involved, rather than selfless. “Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.” Was scholarship and academic work—work, say, in literature, the classics, art, philosophy, even history—doing something, whether for “your country” or for the world? The answer, for scholars from ancient times to the present, has been yes. But the example of Prospero offered a model—indeed, perhaps even a model for “having it all.” For it is Prospero’s attention to his books that leads, ultimately, to the defeat of evil: the shaming and reformation of malefactors, the conversion of sinners, a dynastic marriage that returns his family to political power, and a triumphant return from exile. The ivory tower has turned out to be a command post, even a panopticon.9

Nonetheless, this idealized figure encountered some serious critiques. In the last part of the twentieth century Prospero began to be regularly read (or appropriated) as a colonial exploiter of the indigenous population of what the play text calls an “uninhabited” island—an island already inhabited by Caliban and his mother, Sycorax (“this island’s mine, by Sycorax, my mother”). In Latin America, in Martinique, and elsewhere, versions of the play were written that espoused the cause, and the character, of Caliban. And at the same time there was some attention to the situation of Miranda; her father’s loving protectiveness could also be seen as a kind of condescension. “’Tis new to thee,” his ironic (and indulgent) response to her exclamation “How beauteous mankind is! / O brave new world / That hast such people in’t,” is a put-down as much as an affectionate aside (5.1.186–87).

The father’s irony, in context, is perfectly appropriate; these beautiful people have robbed him of his dukedom and sent him off in a leaky boat to die. But taken out of context “’tis new to thee” has had a career somewhat comparable to the ironization of “brave new world.”

The tension between parents and children, and especially between fathers and daughters, so often encountered in Shakespeare’s plays, is also present in The Tempest. And if the play is read as an allegory of generational conflict, as well as the story of a particular nuclear family (once again, as in all those other Shakespearean incidences, with the mother absent and dead!), then the ironic caution of the father (“’tis new to thee”) to the daughter embracing a brave new world (and a husband, and a move to the city) may well stand, inadvertently and unheeded, as the mantra of the sixties. Critics, in other words, began to rebel against Prospero. If one generation of professors thought of themselves as Prosperos, the next generation would people the academy with Calibans and with resistant and rebellious Mirandas. (And, of course, another way to look at this is to say that once again the internal structure of the play is predictive and determinative: just as it began with the repetition of a rebellion, with the powerless and the powerful switching places, so its metatheatrical afterlife will be a return to that pattern of repetition.)

Magician, academic, scientist, playwright—Prospero, setting Ariel (the mind and imagination) free, acknowledging Caliban (the body, its needs and desires) to be part of him (“this thing of darkness I acknowledge mine”), would wind up, despite himself, in the Freudian position of the heavy father. And yet there remained, at the same time, this transferential desire, this wish to hear Shakespeare’s voice in Prospero’s, to believe—as Coleridge, Edward Dowden, and other Romantic critics long ago had believed—that through his dramatic figure of the father-playwright, Shakespeare was sending us a message, the message of his departure.

HOW CAN WE ACCOUNT FOR the persistent desire to hear the voice of Shakespeare in the voice of Prospero?

It is often observed that we live today in a “celebrity culture,” a culture of public “confession,” of “talking heads” and of “public intellectuals.” The fantasy of putting Shakespeare on Charlie Rose—or on the analyst’s couch—lies very close to the surface of our preoccupation with his elusive authority. And that authority, like the authority of all celebrities, is two-sided: we want Shakespeare’s aura, and we also want his vulnerability.

This is one reason for the persistence of the idea that Shakespeare used one of his most authoritative dramatic characters to confess his own feeling about leaving the world of the theater, an event usually described, in defiance of history, as his “farewell to the stage.”

The Tempest is the site of one of the most quoted of all of Shakespeare’s gorgeous set pieces, a gorgeous set piece about a gorgeous set piece, the speech that begins “Our revels now are ended.”

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits, and

Are melted into air, into thin air;

And like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve;

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.

4.1.148–58

This is one of the passages in Shakespeare that I find real difficulty in reading aloud without a noticeable catch in my throat. It’s written, we might say, to produce that effect. Written by a playwright still at the height of his powers. The pathos it induces is a stage effect, and—as a stage effect—it is very real.

But what this passage certainly is not is “Shakespeare’s farewell to the stage.” The imagined social pathos of his departure from London—which would not come for more than a year after The Tempest, and after he had written at least one more play, Henry VIII, or All Is True, and possibly parts of some others—is something some readers and commentators have wanted to elicit from these words, for a variety of reasons. So far from being “Shakespeare’s farewell,” it is not even, in the play, “Prospero’s farewell,” since it takes place in the fourth act of a five-act play.10

Prospero’s not dying. He’s furious. And worried. Caliban and the other low conspirators are still out there, plotting against his life, and “the minute of their plot / Is almost come” (4.1.141-2). And this play-within-a-play, the masque of Juno and Ceres, takes place in the fourth act. It isn’t till the end of the fifth act, of course, that Prospero releases Ariel, marking the end of his magic (“Be free, and fare thee well”) and speaks his Epilogue. In Patrick Stewart’s performance of the part in the mid-1990s, Stewart, classically trained with the Royal Shakespeare Company but perhaps best-known for his role in Star Trek: The Next Generation, relinquished the microphone amplification that he had used throughout the rest of the play. His voice was suddenly, and only, that of a man, not a magician—or a demigod.

So why do we persist in calling the “revels now are ended speech” Shakespeare’s farewell? (Okay, it’s not his literal farewell, but it’s a kind of farewell, right?) Freud had a name for this: disavowal. The refusal to believe something we really, really don’t want to believe—or rather, in the case of Freud’s patient, and in our case as readers of Shakespeare, the wish not to give up believing something we really, really want to believe. The desire, in this case, for Shakespeare to be talking to us, confessing his vulnerability to us. But like all over-mastering desires, this one—the desire to know what is in Shakespeare’s mind—cannot ever be wholly gratified, or satisfied.

NONETHELESS, IT ABIDES, in criticism, in the theater, and in film. In Peter Greenaway’s 1991 film, Prospero’s Books, the main character, played by the Shakespearean actor John Gielgud, is called in the script at the end “Prospero/ Shakespeare,” and is instructed to address the audience, “his last audience in his last play…as he takes leave of the island, the theater, and possibly his life.”11 Pathos can go no further, and Greenaway is not normally a sentimental man. I think this is hokum, as you can tell. But I’m mentioning Greenaway’s script here not to deplore it but to point out something rather wonderful in it.

Prospero’s Books takes as its structuring principle the “twenty-four books that Gonzalo hastily threw into Prospero’s boat as he was pushed out into the sea to begin his exile.”12 The trope is a complete fantasy, of course. Greenaway invents the number twenty-four, invents the idea, creates an “unscene” that sets the stage (or rather, the screen) for the film.

1. The Book of Water

2. A Book of Mirrors

3. A Book of Mythologies

4. A Primer of the Small Stars

5. An Atlas Belonging to Orpheus

6. A Harsh Book of Geometry

7. The Book of Colours

8. The Vesalius Anatomy of Birth

9. An Alphabetical Inventory of the Dead

10. A Book of Travellers’ Tales

11. The Book of the Earth

12. A Book of Architecture and Other Music

13. The Ninety-Two Conceits of the Minotaur

14. The Book of Languages

15. End-plants

16. A Book of Love

17. A Bestiary of Past, Present, and Future Animals

18. The Book of Utopias

19. The Book of Universal Cosmography

20. Lore of Ruins

21. The Autobiographies of Pasiphae and Semiramis

22. A Book of Motion

23. The Book of Games

24. Thirty-Six Plays

His detailed description of the books is smart, witty, imaginative, and worth reading—a paragraph apiece, including the “fact” that the Book of Travellers’ Tales was much used by children; that Prospero used The Book of the Earth to seek for gold, not for financial gain but to cure his arthritis; and that The Autobiographies of Pasiphae and Semiramis is pornography, that steam rises from its pages whenever the book is opened and it is always warm—and that you have to handle it with gloves. You can see he must have had fun putting this list together—it reads like something out of Jorge Luis Borges. Here’s what he has to say about that last book, the one called Thirty-Six Plays: “Thirty-Six Plays. This is a thick, printed volume of plays dated 1623. All thirty-six plays are there save one—the first. Nineteen pages are left blank for its inclusion. It is called The Tempest. The folio collection is modestly bound in dull green linen with cardboard covers and the author’s initials are embossed in gold on the cover—W.S.”13

By this powerful inventive fiction, one of the books that Prospero takes with him on his voyage is the First Folio of Shakespeare. The play has yet to be written, but the space for it stands waiting. (The Tempest is, in fact, the first play in the First Folio.) This is a version of the play-within-the-play (or the play-within-the-playbook)—a version that depends upon absence rather than presence, and thus upon performativity. It allows for “audience” input, as the process of the film will somehow produce the missing play. But from our point of view, I think the gap is as important as what fills it.

IN MANY ARTICULATIONS OF The Tempest in and for modern culture, Prospero is a defining presence, whether as father and mentor, benign scholar and artist, scientist, artful revenger, unrepentant colonial oppressor and exploiter, or stand-in for Shakespeare the man. In a Freudian allegory of the play as a model for the human mind, or for “humanity,” he would be the conscious subject, whose unconscious could be split into the Ariel part and the Caliban part, whether we call those parts imagination or fantasy or superego (for Ariel) and lust or self-preservation or the id (for Caliban).

But for quite a long time in the modern history of this play, Prospero, although he is in some sense the “main character,” was not the figure who most dominated the cultural imagination. Instead it was Ariel and Caliban, the “airy spirit” and what the list of roles calls the “savage and deformed slave,” who captured the popular imagination—in art, in poetry, in criticism, and, increasingly, in politics and political theory. Here it will be useful to look at the long sweep from Romanticism to the present.

Two of the most popular Shakespeare plays in the nineteenth century were his two “fairy” plays, The Tempest and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Half a century or more before Freud, Romantic critics regarded these plays, with their invisible spirits and magical powers of transformation, as keys to Shakespeare’s poetic imagination. Taken together with the “Queen Mab” speech in Romeo and Juliet, which is also about a tiny spirit who visits people at night and gives them dreams, the fairy plays seemed to say something powerful and consistent about the mind and about creativity.

Like so many other plays (King Lear and Macbeth, for example), The Tempest had been “improved” for modern—that is, eighteenth-century—taste, but was “restored” to the stage by the actor-manager William Charles Macready in 1838. Throughout this whole period, there was a raging debate between people who wanted to see Shakespeare’s plays produced, and people, sometimes very major critics, who thought that any stage production ruined their imaginative potential. The Romantic critic Hazlitt, for example, felt strongly that “poetry and the stage do not agree well together” that “fairies are not incredible, but fairies six feet high are so,” and that “the boards of a theatre and the regions of fancy are not the same thing.”14

But lest you think that all of these Victorian allusions are saccharine or benign, we might consider, for example, a painting called The Stuff That Dreams Are Made Of, by John Anster Fitzgerald, in which a dreaming woman is surrounded by narcotics, bottles, and spirits. It’s clear that her dreams are produced by drugs and drug-induced hallucinations. The title, of course, is an adaptation of Prospero’s famous line. Fitzgerald executed a series of “dream” paintings, like The Artist’s Dream, in which the sleeper encounters frightening fairy creatures that resemble figures in works by Pieter Brueghel or Hieronymus Bosch.15

John Anster Fitzgerald, The Stuff That Dreams Are Made Of

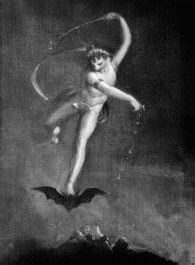

WHEN THE SPIRITS OF The Tempest are depicted or performed, the artist, or the director, does make choices. The artist Henry Fuseli, who created many powerful images from Shakespeare, painted (between 1800 and 1810) an Ariel who was athletic and dancerlike, perched on a bat’s back (as in the song Ariel sings in 5.1.88. “Where the bee sucks, there suck I”). You can see the six-footer problem here. In Macready’s theater production, though, Ariel was played by a woman—this is Priscilla Horton, and the pose is very like that in the Fuseli. Subsequent Ariels throughout the century were female, gentle, and showed quite a bit of leg.

In fact, in productions of Shakespeare’s other fairy play, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the parts of Puck and Oberon (the King of the Fairies) were usually in this period played by women, or by young girls. The Ariel in Charles Kean’s 1857 production was the thirteen-year-old Kate Terry, whose “ethereal” presence struck audiences as preferable even to the “full-grown voluptuous-looking females” (I’m quoting from Kean’s biography) who had played the part before.16 Kean’s Ariel looked like she could, indeed, be compressed within a pine tree. Remember, this is the same Victorian culture that produced Alice in Wonderland and Peter Pan. Hans Christian Andersen, author of fairy tales, was overcome with admiration for this figure, whom he described with a male pronoun (“All in white he stood…”).17 The character was imagined as male; the actor was female. (In the early modern period, of course, the reverse was true: the character—Miranda, Lady Macbeth, Portia—was female, but the actor was male.) Gender onstage is always an illusion. The case of Ariel makes that illusion palpable, since (as Milton’s angels told a curious Adam and Eve) spirits have no sex. (But this does not mean that they always lack desire, as we will see in the epilogue to W. H. Auden’s The Sea and the Mirror, where Ariel confesses his love for Caliban.)

THE GENDERING OF THESE SPIRITS is not without interest, since it creates onstage and conceptual structures: a “female” Ariel has a different relationship to a “male” Caliban than does a “male” Ariel (I put all these gender designations in quotation marks on purpose). And a “female” Ariel would have, perhaps, a different interpretive affinity to the character of Miranda (whose spectral equivalent she might, now, be imagined as being). In fact the female Ariels, since they were active, energetic, and able to fly about the stage and do wonders, quite overshadowed the Mirandas, who were reduced to resisting the command of fathers who secretly hoped they would resist.

Henry Fuseli, Ariel

Daniel Maclise, Priscilla Horton as Ariel

Miranda’s one very strong speech, her attack on Caliban for his attack on her—

Abhorrèd slave,

Which any print of goodness wilt not take

……………………………………

When thou didst not, savage,

Know thine own meaning,…

I endowed thy purposes

With words that made them known.

But thy vile race

…had that in’t which good natures

Could not abide to be with; therefore wast thou

Deservedly confined into this rock.

1.2.354–64

—this very strong and aversive speech was for many years reassigned to Prospero, on the grounds that a sheltered maiden wouldn’t—or shouldn’t—think or say such things.

The nineteenth century introduced a female Ariel, in accordance with its own sense of what a sprite might be like. But most late-twentieth-century Ariels have been male. In a production directed by Mark Lamos at the Hartford Stage Company in 1985 I saw the part played by a male gymnast, who swung athletically in the air on ropes rather than the “fairy wires” that became popular for the Victorian Ariels (and Peter Pan). And as the introduction to the Arden edition of The Tempest points out, the actor Simon Russell Beale performed the part for the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1993–94 as a distinctly resentful figure, quite ready for his freedom.18

“ARIEL” AS A TITLE for a collection of poems—and for a poem—has been adopted by poets from T. S. Eliot to Sylvia Plath (although Plath’s title is actually the name of her favorite horse). The character’s name is related to the Hebrew word for “lion of God” (and is found in modern Israel as a man’s name); Renaissance audiences might also have associated “Ariel” with “Uriel,” the spirit with whom the magician John Dee was said to converse. The pathos of the character, with his insistent desire to be free (twelve years in the pine tree under Sycorax, twelve years’ service for Prospero), is sometimes occluded or lost in these appropriations, which seem to focus on Ariel’s other side, the embodiment of music (“Be not afeard. The isle is full of noises,” says Caliban, who of course has never seen Ariel, “Sounds, and sweet airs, that give delight and hurt not” [3.2.130–31]).

The romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, who thought that poets were the unacknowledged legislators of the world, considered The Tempest his favorite Shakespeare play, and identified with the character of Ariel. Using that name, he wrote a poem (“With a Guitar, to Jane”) to the wife of a friend, calling himself “your guardian spirit Ariel” and calling her husband “thine own prince Ferdinand.” The story has a sad ending, though, and one uncannily related to The Tempest. Shelley and “Ferdinand” (Edward Williams) drowned, shortly after the presentation of the poem and the guitar, when a sudden storm arose off the Italian coast. The boat they were sailing in sank: Shelley had named it Ariel.

YET WHILE “ARIEL” WAS being adopted by poets, it, or he, was also claimed as a principle of freedom and grace by politicians, especially those in Latin America. The Uruguayan philosopher and statesman José Enrique Rodó in 1900 published a book called Ariel that contrasted the elegance and power of Latin American culture with the “barbarism” of Caliban, the forces of northern invaders. In Rodó’s book, which became an enduring best seller, an old teacher “who by allusion to the wise magician of Shakespeare’s Tempest was often called Prospero,” gathers his young disciples about him “one last time,” and talks to them beside a statue of Ariel, beside which it had become his custom to sit.19 “Shakespeare’s ethereal Ariel symbolizes the noble, soaring aspect of the human spirit,” writes Rodó. “He represents the superiority of reason and feeling over the base impulses of irrationality.”20 The plan was to be “evolution,” a “continuous and felicitous acceleration of evolution,” so that “the period of one generation” might be enough time to transform Latin American society.21 The word “evolution” is repeated (“the later evolution of superior races”).22 Rodó goes on to claim that “Ariel will pass through human history, humming, as in Shakespeare’s drama,” until the reformation of society—the animation of “those who labor and those who struggle” is perfected, and he can be set free to return to “the center of his divine fire.”23

Rodo’s optimistic document makes good use of both the Prospero character in his relationship to Ariel and the play’s double ending: Prospero’s departure (from teaching? to death?) and Ariel’s hoped-for freedom. This appropriation of The Tempest signaled a new era in the cultural history of the play. For the rest of the twentieth century it would be thought of—by some at least—as a “New World” play. The geographical location of the island seems (perhaps deliberately) problematic. It seems to be located somewhere between Europe (Naples) and Africa (Tunis), from which the Neapolitans have been voyaging, after Claribel’s wedding to “an African” (the one emphatically black character mentioned in the play). But the references to the “still vexed Bermoothes” or “Bermudas” in act 1, scene 2 suggest that we are in that mysterious and uncanny space still known as the “Bermuda triangle.”

But the identification of Latin American nationalism and culture with “Ariel,” so unproblematic and heralded in 1900, was by the middle of the twentieth century—fifty years later—superseded by an identification with Caliban. Since Caliban had been the abject, the despised and othered one, for so long, we may want to take a moment to see how this came about.

Henry Fuseli, Shakespeare: Tempest, Act I, Scene II

Even before Rodó’s Ariel, Caliban had been cited as the monstrous equivalent of North (and Anglo-) American crudity. In 1898, Nicaraguan Rubén Dario wrote an essay called “The Triumph of Caliban” about U.S. imperialism and aggression in the Spanish-American War.24 On a Manichean reading of Caliban and Ariel—which is, after all, Prospero’s and Miranda’s reading, what we might think of as the dominant-culture reading—Caliban was base, and Ariel noble; Caliban was low, and Ariel high; Caliban was “bad” and Ariel “good.”

What had changed? Over the intervening half a century, the play had come to speak differently to some members of its global audience. Prospero, the “good colonizer” of traditional Anglo-American interpretations of The Tempest, became increasingly regarded—when he was regarded at all—as the “bad colonizer,” the imperialist, imposing his own culture and mores on a victimized Caliban, the native inhabitant (and, as he claims, natural ruler) of the island. All the “civilizing” boasts made by Prospero and Miranda—we taught you (our) language, we taught you (our) cosmology, we taught you (our) manners, we taught you about (our) God—could be regarded as impositions rather than noble gifts. Native and African populations in Latin America were not so grateful for the gift of someone else’s civilization, and in North America (as in France and elsewhere in Europe) a growing consciousness of the colonial present, as well as the colonial past, began to reverse the poles in Shakespeare’s play.

One catalyst here was the publication of a book by a French intellectual and civil servant, Octave Mannoni, in 1950, and its translation into English six years later. In French the book was called Psychologie de la colonisation—in English it was retitled, simply and powerfully, Prospero and Caliban.25

Mannoni’s theory of the “dependency complex” of the native and the unconscious inferiority complex of the colonizer had an enormous effect, pro and con, on discussions of colonial relations. It certainly elicited a ferocious rebuttal from Frantz Fanon. Clearly an appropriation of Shakespeare’s fictional characters, Mannoni’s reading of their relationship is not only an allegory of, but a psychoanalytic “explanation” for, the colonial relation.

Mannoni expresses the belief that “the dependence relationship requires at least two members”—that it is a dialectic.26 And he seeks to find the “exact psychological nature of the relations which form between the European colonial and the dependent native”—a nature he, like Freud, finds “best” described in “the world of some of the great writers,” who “projected them on to imaginary characters placed in situations which, though imaginary, are typically colonial. The material they drew directly from their own unconscious desires,” he says, upping the ante by suggesting that the writers (and in this case Shakespeare) participate in the “complexes” they depict in their fictional characters.27 His examples are two famous literary dyads: Prospero and Caliban, and Robinson Crusoe and Friday.

Prospero, says Mannoni, is “the least evolved of all these literary figures, according to the criteria of psychoanalysis,” because, as a magician, he doesn’t have to have a good grasp of ordinary interpersonal relations.28 He is attracted to solitude, in part because “if the world is emptied of human beings as they really are, it can be filled with the creatures of our own imagination: Calypso, Ariel, Friday.”29 In other words, to use the language of modern pop psychology, Prospero prefers “imaginary friends” to real ones. Mannoni thinks Miranda is healthier, or better adjusted. When she sees Ferdinand and the other Neapolitans, and bursts out with her famous words of admiration (bringing her name to life), “O brave new world / That has such people in’t,” (5.1.86-7) Miranda is making an “adjustment” that her “neurotic father had so surely missed”—and that he confirms in his scornful dismissal, “’Tis new to thee.”30

Colonial life, says Mannoni, is “the nearest approach possible to the archetype of the desert island,” and people who choose such a life are avoiding adult reality.31 “Man [notice the recurrence of this keyword, yet again] is both Ariel and Caliban, and we must recognize this if we are to grow up.” “This same unconscious tendency” that led Shakespeare to write The Tempest “has impelled thousands of Europeans to seek out oceanic islands…or, alternatively, to go and entrench themselves in isolated outposts in hostile countries.”32

As for the “dependency complex” of the colonial natives, “it would be hard,” says Mannoni, “to find a better example of it in its pure state” than in the figure of Caliban, who is delighted to find a new master in Stephano and is eager to abase himself and show loyalty to this unworthy drunken butler. “The dependence of colonial natures is a matter of plain fact. The ensuing encounter between the European’s unconscious and a reality all too prepared to receive its projects is in practice full of dangers.”33 Mannoni includes a substantial and detailed reading of The Tempest, which is not in itself an unconvincing reading. Where his account is deeply troublesome is in his mapping of this story, unproblematically, onto so-called natives and so-called colonials. “The typical colonial is compelled to live out Prospero’s dream, for Prospero is in his unconscious as he was in Shakespeare’s.”34 The “Prospero complex,” as Mannoni calls it, is probably present, even if repressed, in any man who “chooses a colonial career.”

This book, we might recall, was written in 1948, published in France in 1950, and translated into English in 1956. It appeared before various interested readerships at the height of colonial concern and the beginning of decolonization. Mannoni himself had been an official in Madagascar, one of France’s largest colonies. His dual identity, as psychoanalyst and as government administrator, is not unusual in the context of French (or other European) intellectuals.

In 1952, Frantz Fanon, born in Martinique, who had fought with the Free French in World War II and remained in France to study psychiatry, published Black Skin White Masks, his extraordinary account, part manifesto and part analysis, of his experience as a black intellectual in a France permeated with racism, conscious and unconscious. Fanon, too, analyzed the relationship of the colonizer and the colonized. Among his strong influences was Hegel (the Hegel presented in Alexandre Kojeve’s famous Paris lectures). And among his targets, in the chapter, “The So-Called Dependency Complex of Colonized Peoples,” not surprisingly, was Mannoni’s Prospero and Caliban: Psychology of Colonization.

Fanon is superbly dismissive of Mannoni’s thesis, which he summarizes in this way: “It becomes obvious that the white man acts in obedience to an authority complex, a leadership complex, while the Malagasy obeys a dependency complex. Everyone is satisfied.” Mannoni, he thinks, completely disregards issues of race and race prejudice, the imperative on the black man to “turn white or disappear.” Here is what Fanon says about The Tempest: “Prospero, as we know, is the main character of Shakespeare’s comedy, The Tempest. Opposite him we have his daughter, Miranda, and Caliban. Toward Caliban, Prospero assumes an attitude that is well known to Americans in the southern United States. Are they not forever saying that [black men] are just waiting for the chance to jump on white women?”35 The “complex,” Fanon argues, is in the culture, not in the buried childhood psyches of the individuals. And as for the idea that “the dependency complex” is intrinsic to the native populace, “it appears to me that M. Mannoni lacks the slightest basis on which to ground any conclusion applicable to the situation, the problems, or the potentialities of the Malagasy in the present time.”36

This is a French-on-French dispute, a dispute between two French cultural theorists with psychoanalytic training. Fanon became, in the following year, the head of the psychiatry department in a hospital in Algeria; in 1956, appalled by stories of torture told him by his patients, he resigned his government post and began working for Algerian independence. He found the colonial mission at odds, completely, with his profession of psychiatric practice.

What is especially fascinating and germane here is how central the story of Prospero and Caliban—and indeed, in its details, the story also of Miranda, Gonzalo, Ferdinand, and others—was to the cultural reading, the reading of culture, in this case.

Fanon was a Martinican; so was the playwright Aimé Césaire, who in 1969 wrote his own version of The Tempest, a play called Une Tempête, in which Caliban is a field hand and Ariel a mulatto house servant. Here is a brief passage (in translation) of Caliban’s words to Prospero:

You must understand, Prospero,

for years I bowed my head,

for years I stomached it,

stomached all of it:

your insults, your ingratitude,

and worst of all, more degrading than all the rest,

your condescension.

But now it’s over!

Over, do you hear!

Of course, for the moment you’re still

the stronger.

But I don’t care two hoots about your power,

or your dogs, either,

your police, or your inventions!

…………………………………

Prospero, you’re a great illusionist:

you know all about lies.

And you lied to me so much,

lied about the world, lied about yourself,

that you ended up by imposing on me

an image of myself:

underdeveloped, in your words,

incompetent,

that’s how you forced me to see myself,

and I hate that image!

…………………………………

I know that one day

my bare fist, my bare fist alone,

will be enough to crush your world!

The old world is falling apart!

…………………………………

you can get the hell out

You can go back to Europe.

But there’s no hope of that!

I’m sure you won’t leave!37

At the end of Césaire’s version of The Tempest Prospero indeed decides to remain on the island with Caliban and sends Antonio and Gonzalo back to Naples with Ferdinand and Miranda. Years go by; Prospero ages and grows cold. “Ah, well, my old Caliban,” he says. “We’re the only two left on this island, just you and me. You and me! You-me. Me-you!”38

But when he calls out, Caliban is gone, and from offstage the audience hears the cry of “LIBERTY!”39

THE LATE 1960S WERE in the midst of a period of decolonization (the end of official European—or U.S.—rule) in countries from northern and southern Africa to the Caribbean, the Indian peninsula, and the south seas. In the Caribbean and in Latin America, in that same year, 1969, The Tempest and its main characters were cited as prescient forerunners. And again (in Spanish-speaking former colonies) it was Caliban, not Ariel, who had become the hero. The Cuban Roberto Fernández Retamar, a poet, essayist, and literary critic who became the cultural spokesman for Fidel Castro, wrote a much-cited and much-republished essay called “Caliban: Notes Toward a Discussion of Culture in America.” As Retamar wrote:

Our symbol is not Ariel, as Rodó thought, but Caliban. This is something that we, the mestizo inhabitants of these same isles where Caliban lived, see with particular clarity: Prospero invaded the islands, killed our ancestors, enslaved Caliban, and taught him his language to make himself understood. What else can Caliban do but use that same language—today he has no other—to curse him, to wish that the “red plague” would fall on him? I know no other metaphor more expressive of our cultural situation, of our reality…. [W]hat is our history, what is our culture, if not the history and culture of Caliban?40

We might notice here that Caliban’s racial or ethnic identity is really a role, not an identity—that is to say, it varies from context to context, depending upon the national, colonial, or relational situation. Scholars concerned with Shakespeare’s sources and influences have suggested every early modern category of “otherness” to Englishmen, from Native American to Irish—all of them wild men or “natives” that explorers of the time would have encountered in their travels. Voyages of exploration and discovery had brought Native Americans, alive and sometimes dead, from the New World to the king’s court. Notice the moment in The Tempest when the commercially minded Trinculo discusses with himself the possibility of exhibiting Caliban in England for profit: “There would this monster make a man. Any strange beast there makes a man…When they will not give a doit to relieve a lame beggar, they will lay out ten to see a dead Indian” (2.2.28–31).

Modern productions in the United States and Britain often cast Caliban as nonwhite. But, as we saw with Shakespeare Behind Bars, a white, blond Caliban can indeed be very effective. It depends upon the reasons (fictional, cultural, experiential, performed, and performative) for his abjection.

In fact, as the Prospero and Caliban dynamic (whether unpacked by Mannoni, Fanon, or Fernández Retamar) might suggest, “Prospero” and “Caliban” are not only characters, but also positions in a structure: Dominator/ dominated. Exploiter/exploited. Master/slave. Parent/child. Teacher/student. Insider/outsider. Mind/body. Each creates the role of the other, as well as his own. And as the master/slave discourse, whether in Hegel or elsewhere, has compellingly suggested to modern culture, the apparently abjected partner is often in charge of the scene.

We have been tracing the characters of The Tempest as they have been recast as social roles, but it would be equally true to claim that this play and its characters and language have had a powerful effect upon the history of poetry. The isle is full of noises, and Ariel as invisible singer—as well as fearsome Harpy and vengeful sprite—haunts the stage, and the play.

Full fathom five thy father lies.

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes;

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

1.2.400–5

The song sung by Ariel to Ferdinand haunts T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, where “Death by Water” is a constant theme.41

But often it is Caliban who seems to have most caught the poetic imagination, whether in Robert Browning’s dramatic monologue, “Caliban Upon Setebos,” or in W. H. Auden’s bravura performance in Chapter III of his long poem The Sea and the Mirror, a brilliant chapter, in the prose style of the late novels of Henry James, called “Caliban to the Audience.”

What is the appeal of Caliban to poets? He is a fan of music, for one thing, as his great speech demonstrates:

Be not afeard. The isle is full of noises,

Sounds, and sweet airs, that give delight and hurt not.

Sometimes a thousand twangling instruments

Will hum about mine ears, and sometimes voices

That if I then had waked after long sleep

Will make me sleep again; and then in dreaming

The clouds methought would open and show riches

Ready to drop upon me, that when I waked

I cried to dream again.

3.2.130–38

That the speech is spoken to the tone-deaf Stephano and Trinculo suggests that it is really addressed to the audience, or to himself.

Robert Browning’s “Caliban Upon Setebos, or Natural Theology in the Island” was first published in 1864, a few years after the publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859). “Natural theology” is opposed to “revealed theology” or “revealed religion”—it’s the attempt to find and test the existence of God (or a god, in this case) without any supernatural manifestations. Setebos is the god of Caliban’s mother, Sycorax, whom Prospero preempted on the island. The proof of his existence is in his similarity to Caliban (notice the refrains at the end of the verse paragraphs, “So He”):

Would not I smash it with my foot? So He.

’Shall some day knock it down again: so He.

’Doth as he likes, or wherefore Lord? So He.42

Caliban imagines that Setebos himself is subject to a higher being he describes only as “the Quiet”—an unapproachable, impersonal force, very unlike the highly personalized, cruel, and unpredictable Setebos, always spelled with a capital H for the pronoun. Caliban speaks of himself in the third person throughout the poem. (Brackets inserted by the poet at the beginning and end represent his unspoken inner thoughts.) Like all of Browning’s dramatic monologues (such as “My Last Duchess”) the speaker here is revealing more about himself than he knows or intends. “The best way to escape His ire / Is, not to seem too happy.”43 The poem ends with a storm—we could call it a tempest—(“there, there, there, there, there / His thunder follows!”). Having dared to imagine Setebos either caught and conquered by the Quiet, or merely dozing off and dying, he decides he is being punished: “Fool to gibe at Him! / Lo! ’Lieth flat and loveth Setebos!”44

This is one picture of Caliban produced by Victorian England. But here is a very different one:

The nineteenth century dislike of Realism is the rage of Caliban seeing his own face in a glass.

The nineteenth century dislike of Romanticism is the rage of Caliban not seeing his own face in a glass.

These are maxims that Oscar Wilde added in a preface to his then-scandalous novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, published in 1891.45 The book was an enormous success—widely read, and also widely denounced as immoral. In reply to his critics, Wilde added, for a preface, a defiant set of maxims about art and life, including “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written. That is all,” and “No artist has ethical sympathies. An ethical sympathy in an artist is an unpardonable mannerism of style,” and “All art is quite useless.”46 The “Caliban” aphorisms are among the most frequently quoted. “Caliban” is the boorish, anti aesthetic reader, or critic, the one who dislikes and disapproves rather than responding. “Rage” rather than exquisite sensibility is his only emotion. And of course The Picture of Dorian Gray is, exactly, a novel about a monstrous double, hidden from sight: a portrait, locked away, that tells the truth about the degeneration of the beautiful hero.

James Joyce has one of his characters quote (or misquote) this maxim at the beginning of his novel Ulysses. In the opening pages of the first chapter, Buck Mulligan finds Stephen Dedalus shaving in front of a cracked mirror and takes it away from him: “The rage of Caliban at not seeing his face in a mirror,” he says, and adds, “If Wilde were only alive to see you.”47 Stephen mutters that the cracked looking glass is a symbol of Irish art. But Wilde’s aphorism had clearly by this time (1922) become a recognizable, and quotable, classic. This is a Caliban more like the “Barbarian” satirically described by Matthew Arnold in Culture and Anarchy than like the Darwinian figure of Browning’s poem. For Arnold’s “Barbarians” were the aristocracy—willful, athletic, individualistic, fond of field sports, possessing culture only in an exterior sense, lacking in sensibility and spirit.

The rage of Caliban at seeing—or not seeing—his face in a mirror: in W. H. Auden’s long poem The Sea and the Mirror: A Commentary on Shakespeare’s The Tempest, the mirror is associated with Ariel, and with Art—the Sea with Caliban and Life.48 Auden as a poet went through at least three phases—Freudian, Marxist, and Christian—and elements of each of these are present in his poem. Prospero is the ego, Caliban the id. The poem is divided into sections: Preface (The Stage Manager to the Critics); Chapter I (Prospero to Ariel); Chapter II (The Supporting Cast); Chapter III (Caliban to the Audience); Postscript (Ariel to Caliban. Echo by the Prompter).

The real tour de force, as all critics have agreed, is the long prose section of Chapter III, Caliban to the Audience, in which he begins, in impeccably Jamesian tones, by announcing that he is the inevitable substitute for the playwright:

If, now, having dismissed your hired impersonators with verdicts ranging from the laudatory orchid to the disgusted and disgusting egg, you ask, and, of course, notwithstanding the conscious fact of his irrevocable absence, you instinctively do ask for our so good, so great, so dead author to stand before the final lowered curtain and take his shyly responsible bow for this, his latest, ripest production, it is I—my reluctance is, I can assure you, co-equal with your dismay—who will always loom thus wretchedly into your confusing picture, for in default of the all-wise, all-explaining master you would speak to, who else at least can, who else indeed must respond to your bewildered cry, but its very echo, the begged question you would speak to him about.49

Caliban then proceeds to ventriloquize, to talk in the voice of the audience, offering a complaint to the playwright that in his too-famous phrase about holding the mirror up to nature he allowed for a reversal of value between the real and the imagined, with the dangerous result that art is made to seem as if it should be the model or “cause” of life, rather being than the “accidental effect” of living. It is this inversion, this reversal of the traditional poles of “art” and “life,” that is the imagined audience’s concern, and Auden’s point:

Is it not possible that, not content with inveigling Caliban into Ariel’s kingdom, you have also let loose Ariel in Caliban’s?…Where is He now? For if the intrusion of the real has disconcerted and incommoded the poetic, that is a mere bagatelle compared with the damage that the poetic would inflict if it ever succeeded in intruding upon the real. We want no Ariel here.50

Responding to the audience in his own voice, Caliban addresses the audience “on behalf of Ariel and myself” and points out that he and Ariel work together, as the picture of what is and what might be:

you have now all come together in the larger colder emptier room on this side of the mirror which does force your eyes to recognize and reckon with the two of us, your ears to detect the irreconcilable difference between my re-iterated affirmation of what your furnished circumstances categorically are, and His successive propositions as to everything else which they conditionally might be.51

“Introducing ‘real life’ into the imagined,” to quote Auden’s phrase about the Caliban chapter, was, I think, the move of modernity.52 In the modern period Caliban has been, by turns, a “missing link,” a natural theologian, a revolutionary, an enslaved or scorned or exoticized “native,” a foe of aestheticism; Auden makes him an actor. Furthermore, he puts him in the place previously occupied by Prospero, at the end of the play, in the epilogue, engaging with the audience—but in this case from a position of strength. And from the other side of the curtain, or the mirror. In putting his Caliban in charge, it was, as he wrote to a friend, “exactly as if one of the audience had walked onto the stage and insisted on taking part in the action.”53

Caliban became the Prospero of the twentieth century. It remains to be seen who will hold the staff and book, and wear the magic robe of art, in the twenty-first.