TWO

ROMEO AND JULIET

The Untimeliness of Youth

IN THE FILM Shakespeare in Love the young playwright William Shakespeare suffers from the malady that the twentieth century would call “writer’s block.”1 His current project, Romeo and Ethel the Pirate’s Daughter, is stuck and going nowhere. When he falls in love with a noblewoman cross-dressed as a boy, who auditions for the part of Romeo, Will courts her in scenes that closely echo moments from Romeo and Juliet—including the famous “balcony scene”—and bits of dialogue from this forbidden courtship will later make their way into the script of his new play, now rewritten and retitled. The inspiration of his secret muse has, in this cultural fantasy, made Will into a better playwright. Thus in her bedroom he speaks the lines that will become Juliet’s speech in the orchard (or “balcony”) scene: “My bounty is as boundless as the sea, / My love as deep” (2.1.175–76); later he brings her a copy of a “new scene” that is the famous nightingale-and-lark aubade from act 3, scene 5.

To make the connection between modern film and Shakespeare’s play even more overt, the authors of the clever screenplay, Marc Norman and Tom Stoppard, have given the lady a nurse-companion, closely indebted to Juliet’s Nurse in tone, in spirit, and, occasionally, in language. In the denouement, these “star-crossed lovers,” although they are not destined to live (together) happily ever after—since he is married and she is engaged to the fictitious Earl of Wessex—play the parts of Juliet and Romeo onstage, in a production that delights the theater audience, including the queen, and sets Shakespeare on the path to success and literary immortality. (For this performance, it might be noted, the lady has forsaken her male attire and plays Juliet, leaving Romeo to the amorous Will.)

The film—which won the Academy Award for Best Picture in 1998. does not pretend to historical accuracy. The only one of its deliberate and often delicious falsifications I feel impelled to “correct” here is the idea that Shakespeare’s successful and memorable plays begin with Romeo and Juliet (c. 1597), thus relegating to the reputational dust heap such works as Love’s Labour’s Lost, The Comedy of Errors, Titus Andronicus, Richard III, and the three parts of Henry VI. It is not the case that Shakespeare was an average playwright who suddenly became a great one. And it is certainly not the case that some life-changing external event, even falling in love, switched the gears on his writing and permitted him to become himself.

But there is a reason, or a modern cultural logic, why Romeo and Juliet is the fulcrum of this fictional story about the “real” Shakespeare. Shakespeare’s play has become the normative love story of our time, a cliché so firmly established that the screenwriters can assume the audience will be amused by the idea of Romeo and Ethel the Pirate’s Daughter, instantly recognizing it as “wrong”—and that virtually any love scene, when played from a balcony with the female beloved above and the male lover below, is automatically assimilated to a version of Romeo. (One example I noted some time ago took place between two St. Bernard dogs in the film Beethoven’s 2nd ).2 Romeo and Ethel may have the ring of bathos to modern ears, but the couple so famous to us now went by a variety of names in the period immediately prior to Shakespeare’s play, from Romeo and Giulietta (or Julietta) to Halquadrich and Burglipha to the title characters of Shakespeare’s immediate source, The Tragicall Historye of Romeus and Juliet, a long poem by Arthur Brooke.3 In the French version, by Adrien Sevin, the lovers Halquadrich and Burglipha belong, respectively, to families called Phorhiach and Humdrum. The classical version, from Ovid, was the story of Pyramus and Thisbe, brilliantly sent up by Shakespeare in the love comedy he wrote at the same time as Romeo, A Midsumer Night’s Dream.

Even “Romeus” will strike modern ears as an error, though. The name “Romeo” has long since passed into the English language, although, peculiarly, with a meaning pretty much opposite to that of Shakespeare’s fatally faithful wooer. A “Romeo” today, with or without a capital R, is a ladies’ man, a seducer, a “habitual pursuer of women”4—not a young man so transformed by the singularity of his love that he prefers death with her to life without her. Anne Bernays’s novel Professor Romeo (1988) is about a tenured professor of psychology at Harvard who is charged with the sexual harassment of his female students. The novel’s title, it can be imagined, was thought to be self-explanatory; readers were not to expect an idealized story of pure, self-sacrificing passion.

How Romeo became a Lothario is in itself an interesting question.5 I suspect it may have to do with putting a kind of ironic distance between the speaker and the idea of an all-consuming young love—or, alternatively, with a recognition of the inevitable narcissism that insists on the immediacy and primacy of the love object; Shakespeare’s Romeo, we might pause to remember, first thought himself totally and hopelessly in love with Rosaline, a character who never appears in the play. When the lovestruck Romeo, fresh from his nighttime visit to Juliet’s garden, turns up early at Friar Laurence’s cell, the Friar, rather like a modern psychotherapist, questions his charge:

What a change is here!

Is Rosaline, that thou didst love so dear,

So soon forsaken? Young men’s love then lies

Not truly in their hearts, but in their eyes.

…………………………………………

Lo, here upon thy cheek the stain doth sit

Of an old tear that is not washed off yet.

If e’er thou wast thyself, and these woes thine,

Thou and these woes were all for Rosaline.

And art thou changed? Pronounce this sentence then:

Women may fall when there’s no strength in men.

2.2.65–80

But perhaps of more central interest, in the interactions between Shakespeare and modern culture, is the question of how “Romeo and Juliet” became the unquestioned modern cultural shorthand for romantic love.

As our brief survey of Shakespeare’s sources will have suggested, this story of two feuding “households” (Prologue 1) was hardly a household word in the early modern period. Shakespeare does seem to have drawn on at least two English-language versions,6 and there is some evidence—based on reprintings of Brooke—that “the story of Romeo and Juliet was popular in the reign of Elizabeth.”7 But certainly the lovers had not attained anything like mythic status. There is no mention of “a Romeo” or “Romeos” as a generic type in any other of Shakespeare’s plays. By comparison, consider the situation of another figure celebrated in the literature of the period: Troilus, of that other pair of “star-crossed lovers,” Troilus and Cressida. Mentions of Troilus—knowing, shorthand mentions, assuming the audience’s familiarity with the reference—appear in The Taming of the Shrew, in Much Ado About Nothing, in The Merchant of Venice, and in Twelfth Night, as well as in “The Rape of Lucrece.” Cressida is mentioned not only in Merchant and in Twelfth Night but also in Henry V and All’s Well That Ends Well. Pandarus, the go-between, who plays the same structural role in the Troilus and Cressida story as do the Friar and the Nurse in Romeo, is mentioned by name in The Merry Wives of Windsor as well as in Twelfth Night, and his name had indeed by then become a household word, in lowercase, appearing as a noun and also as a verb in several plays. In short, there was a ready-made pair of lovers available, a pair already so legendary in Shakespeare’s time that the playwright has them speculate in his play, with maximum dramatic irony, upon the archetypes that—as the audience would clearly recognize—they had already, by that time, become:

TROILUS True swains in love shall in the world to come

Approve their truth by Troilus. When their rhymes,

Full of protest, of oath and big compare,

Want similes, truth tired with iteration—

“As true as steel, as plantage to the moon,

As sun to day, as turtle to her mate,

As iron to adamant, as earth to th’ centre”—

Yet, after all comparisons of truth,

As truth’s authentic author to be cited,

“As true as Troilus” shall crown up the verse

And sanctify the numbers.

CRESSIDA Prophet may you be!

If I be false, or swerve a hair from truth,

When time is old and hath forgot itself,

When waterdrops have worn the stones of Troy

And blind oblivion swallowed cities up,

And mighty states characterless are grated

To dusty nothing, yet let memory

From false to false among false maids in love

Upbraid my falsehood. When they’ve said “as false

As air, as water, wind or sandy earth,

As fox to lamb, or wolf to heifer’s calf,

Pard to the hind, or stepdame to her son,”

Yea, let them say, to stick the heart of falsehood,

“As false as Cressid.”

PANDARUS Go to, a bargain made. Seal it, seal it. I’ll be the witness. Here I hold your hand; here my cousin’s. If ever you prove false one to another, since I have taken such pain to bring you together, let all pitiful goers-between be called to the world’s end after my name: call them all panders. Let all constant men be Troiluses, all false women Cressids, and all brokers-between panders. Say “Amen.”

3.2.160–90

It is certainly understandable that a later age—one that would, with however different a reason, be dubbed “Romantic”—might prefer “positive” archetypes of love to these ironic self-namings. But the fact remains that Troilus and Cressida, famous—or infamous—from their appearances in major works by Boccaccio, Chaucer, Robert Henryson, and Shakespeare, were not only ready to hand, but already celebrated. How many modern-day teenagers, or modern-day adults, for that matter, can identify them, or tell their stories? Or what about that third pair of larger-than-life lovers linked by name in a Shakespearean love tragedy, Antony and Cleopatra?

All three plays have very similar structures: a “feud” (in Romeo and Juliet, between the Montagues and the Capulets; in Troilus and Cressida, between the Trojans and the Greeks—a.k.a. the Trojan War; in Antony and Cleopatra, between Rome and Egypt); go-betweens and enablers who broker love affairs (Nurse and Friar; Pandarus and Ulysses; Enobarbus and Octavius); a well-meant intervention that goes wrong; and a tragic end that reflects upon the transformative role of the lovers as it moves forward into a diminished political and social world. But where Romeo and Juliet are relative unknowns (prior to the celebrity of Shakespeare’s play), the other pairs of lovers are virtually equivalent, in the early modern period, to the idea of love itself. Octavius Caesar’s final speech in Antony and Cleopatra underscores the unparalleled status of the lovers: “No grave upon the earth shall clip in it / A pair so famous” (5.2.349–50). Like Romeo and Juliet, they are to be reunited in death—and in art.

The Joseph Mankiewicz film Cleopatra (1963) is notorious both for having almost bankrupted the studio, Twentieth Century Fox, and for bringing together the incendiary real-life lovers Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, who met on the set and began their own legendary affair. But aside from this “sword and sandal” epic, which covers the entire life of Cleopatra, and not—like Shakespeare’s play—only the years when she was the “serpent of old Nile,” already “wrinkled deep in time,” the story of these transcendent and world-famous lovers has not retained the mythic status in modern popular culture that it clearly had for Shakespeare’s audience. The romances of older lovers, however passionate, are, it seems, now consigned to On Golden Pond rather than the barge that burned on the water at Cydnus.

So youth and optimism (or rather a kind of optimistic, uncompromised fatalism) would seem to be two things that Romeo and Juliet has to offer, in contradistinction to the stories of lovers far more famous in myth and legend. Does this really account for its modern ubiquity?

I want to approach the question of how two characters called Romeo and Juliet became the phenomenon (or, in postmodern commercial parlance, the brand) “Romeo-and-Juliet” first rather obliquely, following the signifier of “youth,” and its supposed antonym, “maturity,” as the term is applied to both persons and plays. This is a move that will take us back to the fantasy belief, depicted in Shakespeare in Love, that there was a turning point for Shakespeare when he changed from being a tyro (or, in the film’s harsher comic vision, a hack) to being “Shakespeare.” In Norman and Stoppard’s film, which based the “love story” of the playwright on the plot of Romeo and Juliet, that play—and its supposedly “real” inspiration—is the turning point. For many traditional critics of Shakespeare, however, Romeo and Juliet has remained in a kind of neutral zone called “the early tragedies,” sometimes bracketed with Titus Andronicus, and set off clearly, by chronology and by certain interpretative claims about quality and theme, from what are termed, by contrast, “the mature tragedies,” beginning with Hamlet.

The phrase “mature tragedies” has become conventional as a literary-critical term of art. It appears in the titles of books of Shakespeare criticism,8 it is used confidently by the Encyclopedia Britannica, and it seems to point to a period in the playwright’s work—and life—that is understood to be especially productive and significant. A. C. Bradley, the influential critic whose published lectures on Shakespearean tragedy set the tone for early-twentieth-century discussions, confidently described “Shakespeare’s tragic period” as the period 1601 to 1608, even though Shakespeare “wrote tragedy—pure like Romeo and Juliet; historical, like Richard III—in the early years of his career of authorship,” when he was also writing early comedies. Bradley regarded Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, and Macbeth as plays that are central to understanding the major contribution of Shakespeare. By contrast, Romeo and Juliet, he insists, “is an early work, and in some respects, an immature one.”9 The play, that is to say, has been accused, sometimes explicitly, sometimes by implication, of the same immaturity that characterizes its protagonists.

The German Romantic critic A. W. Schlegel had suggested something of the same, in more highly wrought language: “If Romeo and Juliet shines with the colours of the dawn of morning, but a dawn whose purple clouds already announce the thunder of a sultry day, Othello is, on the other hand, a strongly shaded picture: we might call it a tragical Rembrandt.”10 In this classic example of “purple prose” the language is literally purple, but Schlegel’s “dawn” image—and the implication of dangerous weather on the horizon—is drawn directly from Shakespeare’s play, not only from the aubade of act 3, scene 5 ( Juliet’s “Wilt thou be gone? It is not yet near day”) but also from her fear, in the orchard/balcony scene, that their love may be “too rash, too unadvised, too sudden, / Too like the lightning which doth cease to be / Ere one can say it lightens” (2.1.160–2). Haste, youth, and impetuousness—the very elements that make this play so appealing to a modern audience, and indeed, we might say, make it so “modern”—are tied to an ominous anticipation of futurity.

“Mature” as a term within Shakespeare’s plays is sparingly, but tellingly, used: the “more mature dignities” of the grown-up Leontes and Polixenes in The Winter’s Tale are cited as the reason these former “young play-fellows” have grown apart (1.1.25); the contrast between youth and maturity is again made at the beginning of Antony and Cleopatra—“As we rate boys who, being mature in knowledge, / Pawn their experience to their present pleasure, / And so rebel to judgement” (1.4.31–33)—and yet again at the beginning of Cymbeline (1.1.48). “Dignities,” “experience,” “judgement” are the qualities to be expected of the “mature.” The word implies age, gravity, consideration—and perhaps a slightly excessive self-distancing from the instinctive energies, pleasures, and rebellions of youth. Manifestly there is a time for maturity to replace heedlessness—the rejection of Falstaff by a newly matured King Henry V at the end of Henry IV, Part 2 seems like a case in point. But as audience responses to this rejection scene have demonstrated, there is a certain sympathy generated by playful irresponsibility. Falstaff’s comic averral in Part 1, “They hate us youth” (2.2.78), spoken by a character who, by his own subsequent accounting, is nearing the age of sixty, raises the question of whether youth is an age, a stage, or an attitude. In the history plays, as war, death, and the responsibilities of political succession overtake the playing space of the tavern, Falstaff’s claim of eternal “youth” is disallowed by the stern new king: “How ill white hairs becomes a fool and jester” (Henry IV, Part 2 5.5.46).

Given Romeo and Juliet’s almost automatic modern association with youth culture, and the by-now-proverbial identification of its title characters, it is of some interest to remind ourselves that for many years the star parts were those of Mercutio and the Nurse—as is often still the case on the stage today. Dryden famously reports the story, traditional by his time, that Shakespeare said that “he was obliged to kill Mercutio in the third act, lest he should have been killed by him.”11 Samuel Johnson, retorting, does not doubt that Shakespeare could have kept him alive if he wished, without danger of the play being eclipsed, but says nonetheless that “Mercutio’s wit, gaiety and courage, will always procure him friends that wish him a longer life.” As for the Nurse, to Dr. Johnson she is “one of the characters in which the author delighted: he has with great subtilety of distinction, drawn her at once loquacious and secret, obsequious and insolent, trusty and dishonest.”12 In his notes on the play, this great eighteenth-century editor has nothing at all to say about either Romeo or Juliet as characters except that Romeo shows “thin” wit at one point and “involuntary cheerfulness” at another, and that Juliet “plays most of her pranks under the appearance of religion; perhaps Shakespeare meant to punish her hypocrisy.”13

The humorous characters, like the mercurial Mercutio and the earthy Nurse, were what appealed to earlier audiences. The young lovers, the focus of our modern gaze, were all very well, but it was Mercutio or the Nurse who threatened to run away with the show. Furthermore—and this was a problem that would persist—the actors who played Romeo and Juliet were often too old for the parts. Performed by Sir William Davenant’s company in the Restoration period, the play earned a scathing critique from that inveterate theatergoer Samuel Pepys: “To the Opera,” Pepys wrote in his Diary, “and there saw ‘Romeo and Juliet,’ the first time it was ever acted, but it is a play of itself the worst that ever I heard in my life, and the worst acted that ever I saw these people do, and I am resolved to go no more to see the first time of acting, for they were all of them out more or less.”14

John Philip Kemble played Romeo in 1789 in a Drury Lane production, opposite the famous actress Sarah Siddons, then thirty-four. As her biographer noted, “time and study had stamped her countenance” by that time “too strongly for Juliet.” Siddons would have played the part more convincingly fourteen years earlier, he thought, when she would more closely have resembled Juliet’s “youthful loveliness.”15 Kemble is described by his biographer as equally unsuited to the part of Romeo: “Youthful love was never well expressed by Kemble,” he wrote. “The thoughtful strength of his features was at variance with juvenile passion.”16 David Garrick, in his 1748 production, had been a thirty-one-year-old Romeo; Charles Kemble, John Philip Kemble’s younger brother, was still playing the part in 1819, at age forty-four. His daughter Fanny, who became a celebrated actress in her own right, was nineteen when she first performed Juliet, cast against a Romeo who was, she later wrote, “old enough to have been my father.” Her father himself was in the production, too, now playing Mercutio; he would then have been fifty-four years old.17 Her mother came out of retirement, in this family production, to play the part of Lady Capulet.

THROUGHOUT THIS PERIOD, I might point out, the final scene was played as rewritten by David Garrick, with Juliet awakening before Romeo’s death. Shakespeare’s version of the last scene, in which each dies alone, was not restored until the middle of the nineteenth century.

One of the most successful Romeos of this period was a woman, Charlotte Cushman, who played opposite her sister Susan as Juliet. Cushman’s production ran for eighty-four performances, and drew rave notices. It was not a stunt, but a straightforward portrayal, admired by audiences. Romeo was perhaps her most celebrated role, although she also played Lear, Shylock, and Hamlet in the course of her career. A poster advertising Cushman’s Hamlet in 1861 called her “a lady universally acknowledged as the greatest living tragic actress.” Charlotte Cushman was a lesbian and had a number of famous lovers; rumors about her life and even her relationship with her sister were said to have helped fill the London theater seats for their Romeo and Juliet. One audience member reported that the portrayal of Romeo was so “ardently masculine” and the Juliet so “tenderly feminine” that “the least Miss Cushman could do, when the engagement was over, was marry her sister.”18

Benjamin Wilson, David Garrick and George Anne Bellamy in Romeo and Juliet, V,3

Cushman’s Romeo was not played as a woman—gay or straight—but as a man. She was the most successful and striking of the female Romeos, but not the only one; at least thirteen other women played the part on the American stage from 1827 to 1859.19 (This was some fifty years before Sarah Bernhardt played Hamlet, to great acclaim, on stage and in a brief silent film.)

In Shakespeare’s own time, of course, the part of Juliet would have been played by a boy actor. Transvestite theater was the rule, rather than the exception, on the early modern English public stage (as it was indeed in ancient Greece). What we may regard as “natural” or “real” gender performances (male actors playing men, female actors playing women) are the adaptations from the Renaissance to the modern stage—beginning in England after the Restoration, when the theaters reopened—and when not a few conventional theatergoers protested against the less lifelike performances of women playing women, as compared to the more familiar, and (to them) more persuasive, boys. Conceivably some members of the audience, now and then, watched the performance binocularly, or metatheatrically, seeing both the performer and the role, as today an audience can see both the “real life” performer (say, Patrick Stewart or Dame Judi Dench) and the roles they play on stage or screen. This willing suspension of disbelief is part of what makes drama into theater—as also is the occasional breaking of the frame, through, perhaps, a quotation (by the performer in gesture or onstage attitude) of a signature previous role.

Charlotte Cushman as Romeo

Charlotte and Susan Cushman as Romeo and Juliet

I mention these questions of gender and sexuality because Romeo and Juliet, as the “classic love story” of modernity, has now—inevitably—been staged and adapted for male-male and female-female lovers. One successful example with playgoers was Joe Calarco’s 1998 adaptation, Shakespeare’s R&J, set in an all-boy Catholic prep school where Romeo and Juliet is a proscribed text, and the boys act out the roles and inhabit them. “What could be more dangerous than the first forbidden kiss of literature,” Calarco asked, rhetorically, and answered his own question: “The first forbidden kiss of two schoolboys.” Significantly, for our purposes, he described his play as needing to “radiate with a very young, very male energy” in performance. Very young, very male. Contrast this with Garrick and Kemble. This insistence upon youth is, it might be said, a particular fetish of modernity, especially when it comes to Romeo and Juliet.

One caveat, or at least a small pause to reflect: it seems conceptually possible to think that age on the stage might be as fictive, or as binocular, as gender. There seems no reason why one couldn’t see a “mature” actor as—at the same time—a persuasive teen Romeo or fourteen-year-old Juliet. But in fact this seems seldom to have been the case, and, importantly, it seems to be even less so in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries than in the time of Garrick or Mrs. Siddons. Despite the fact that truisms about youth and love are ubiquitous in the Renaissance and earlier (in the works of poets like Chaucer and Petrarch, as well as Shakespeare), the circumstances of the theater often led to the casting of older actors in the parts of the young lovers. The 1936 film of Romeo and Juliet, directed by George Cukor, starred Leslie Howard, then forty-two, as Romeo, and Norma Shearer, then thirty-four, as Juliet. Shearer was married to Irving Thalberg, the producer, who insisted that Howard play the part under the terms of his MGM studio contract—though Howard protested vehemently to the press about doing so. (There’s some small irony, under the circumstances, in the fact that Thalberg’s nickname was “the boy wonder.”) The film’s Mercutio, John Barrymore, was fifty-four. In the film they do not look old, certainly, but they do look like adults.

Every authority will remind us that this is a casting convention of the time. But that, again, is exactly the point I want to stress. On the one hand we have the play, so regularly classed by critics among the earlier, even “immature,” plays. The Romantic critic Hazlitt indeed claimed—against all available evidence—that it was Shakespeare’s first play. “Romeo and Juliet,” Hazlitt writes, “is the only tragedy which Shakespeare has written entirely on a love-story. It is supposed to have been his first play, and it deserves to stand in that proud rank. There is the buoyant spirit of youth in every line.”20 So the play is early, concerned with love, has “the buoyant spirit of youth” inscribed all over it, and may be, in Bradley’s somewhat more measured or dour account, therefore “immature,” if also “pure” (a word that you will recall he uses to characterize this play’s mode of tragedy). On the other hand, productions of the play, especially well-known or benchmark productions prior to the middle of the twentieth century, have tended to cast older actors and actresses, whose few flashes of youthfulness are often singled out by commentators precisely because these are contrary to the general tone of the “mature” (or even overripe) performance.

It might be imagined that one way of “universalizing” the love story in the play would have been through its translation into ballet, since without the specificity of words, and with the presumptive requirement that the dancers be young, lithe, and visually beautiful, the particulars of the plot would almost directly yield to the embodied ideology of young love. But, as it turns out, the ballet versions of Romeo and Juliet were often star vehicles, and the performers, at least at the beginning, far from young, at least in dance-world terms.

Shakespeare’s plays were identified relatively early as ripe for choreographic treatment. Antoine et Cléopâtre and Les Amours d’Henri IV, ballets based on his plays, were both produced for the Duke of Wurtenberg in the mid-eighteenth century.21 But Romeo and Juliet would surpass these, and all others, from the beginning of the nineteenth century to the present day. The first version, Romeo og Giulietta, produced by Vincenzo Galeotti for the Royal Danish Ballet in Copenhagen in 1811, was the most popular ballet of the season. It was produced, we should note, at a time when there was no Danish translation of the play yet available. The choreographer, Galeotti, had worked in London at a time when the play was performed there, and might have seen a production, but it is far from clear what story the audience thought they were watching. No play by Shakespeare was performed in Copenhagen until 1813. perhaps unsurprisingly, that play was Hamlet, Prince of Denmark.22

In any case, Romeo og Giulietta was not the opening salvo in ballet as the harbinger of youth culture. The Romeo for this first production, Antoine Bournonville (the father of the choreographer of La Sylphide, Auguste Bourn on ville), was fifty-one, and the seventy-eight-year-old Galeotti himself performed as the Monk Lorenzo (the ballet’s version of Friar Laurence). Finesse and grace, not the raw energy of youth, were the criteria.

Sergei Prokofiev’s ballet, composed in 1935 and 1936 under a commission from the Kirov Ballet, immediately ran into political difficulties. Widespread government criticism of “degeneracy” in modern art—largely aimed at the composer Dmitri Shostakovich—touched Prokofiev as well, and while a version of his Romeo and Juliet (which he rewrote only under protest) was danced at the Kirov, with choreography by Leonid Lavrovsky and a great deal of theatrical pantomime and a happy ending—the lovers share a final dance and embrace a new world—a ballet to Prokofiev’s music did not return to the major canon till the 1960s, when John Cranko choreographed it for the Stuttgart Ballet, which then came to the United States in 1969. Rudolf Nureyev and Margot Fonteyn performed the parts, memorably, in a Royal Ballet production by Sir Kenneth MacMillan. Fonteyn was thought to be nearing retirement when her career changed, radically, through the partnership with Nureyev. (She was born in 1919.)

In this instance, then, and perhaps also—who knows?—in the case of the elder Bournonville, it is not that the Romeo and Juliet story so directly mirrors or enacts modern youth, but rather that it seems somehow to confer youth upon these brilliantly successful performers, no matter what their actual ages. Margot Fonteyn begins her career again rather than retiring once she partners with Nureyev. Nureyev’s first experience of dance, at age seven, has been described as “love at first sight,”23 and he described Fonteyn as his soul mate. He came from one world, or “family,” that of Russia and the Kirov Ballet; she came from another, as the prima ballerina of England’s signature company. His defection in Paris (“I am a dead man,” he is said to have said, when it seemed as if he would be sent back to Russia rather than on to a London tour) put him at risk (“And the place death, considering who thou art,” as Juliet says to Romeo in the orchard, or balcony, scene—to which Romeo famously replies, “With love’s light wings did I o’erperch these walls, / For stony limits cannot hold love out, / And what love dares do, that does love attempt” [2.1.106; 108–10.). Nureyev’s all-consuming love is for dance: in the partnership with Fonteyn that love found also a local habitation and a name. The celebrity of Romeo and Juliet as a ballet is intertwined, in modern culture, with the celebrity of this unlikely and perfect couple.

Meantime the story of the Prokofiev ballet is still ongoing. The Joffrey Ballet mounted the first American production in the 1980s, and in July 2008 the choreographer Mark Morris directed the first real world premiere of the ballet as Prokofiev composed and planned it, with support from Prokofiev’s family and from the Russian State Archive, restoring the original ending. A press release issued on behalf of the Mark Morris Dance Group and the Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College, where the premiere was performed, offers the following historical account: “Prokofiev conceived the ballet in 1935 in collaboration with innovative Soviet dramatist Sergei Radlov, who reimagined the familiar tragedy as a struggle for the right to love by young, strong, and progressive people battling against feudal traditions and feudal outlooks on marriage and family. Much of Prokofiev’s score addresses the theme of love’s transcendence over oppression.”24 The analogy is straightforward: Stalin’s repressive regime, where in the arts “conservative neoclassicism supplanted accessible innovation,” is like the repressive parents of the Shakespeare play. Prokofiev—like Romeo?—is helpless to reverse the events in which he has been an unwitting and unwilling participant (“he pleaded to no avail to undo the changes that he had strongly resisted”).25 In the new production the composer will be reunited—long after his death—with the original ballet score and choreography designed expressly for it.

Prokofiev died in 1953, on the same day as Stalin. For three days throngs in Red Square prevented his body from being carried to the headquarters of the Soviet Composers Union for his funeral service. Taped music of the funeral march from Romeo and Juliet accompanied the body; all the living musicians in Moscow were required for Stalin’s state funeral. (In an earlier moment of historical irony, Prokofiev had been awarded the Stalin Prize in 1951, three years after the Soviet Union had formally condemned him.) The great Russian dancer Galina Ulanova is said to have remarked, “Never was a story of more woe than this of Prokofiev and his Romeo.”26

WE ARE NOW PERHAPS in a position to return to a question that puzzled us earlier: why did a relatively unknown love story like that of Romeo and Juliet come to eclipse, in general popularity and cultural citation, high and low, the venerable and famous love stories of Troilus and Cressida and of Antony and Cleopatra? The “answer,” it seems, is the same as the question: it was in part because these were unknown, relatively “new” (and insistently “young”) lovers that their story could be adapted to numerous romantic situations. The quip attributed to Ulanova suggests an archetypal relationship of longing and loss between a creator and a work of art. And the enduring partnership of Nureyev-Fonteyn seemed to demonstrate that the play, rather than being about youth, could produce it, even—or especially—in “mature” performers.

The availability of Romeo and Juliet as a transposable love story, not tied to ancient myth or history like Troilus and Cressida and Antony and Cleopatra, may actually have helped move it in the direction of a modern myth. It would become “generic,” generating its own taglines, but the relative obscurity of its sources was in some ways an asset. Certainly that was the case for high school students liberated from studying Julius Caesar (as had been the norm in the United States through the 1950s) and introduced to Shakespeare instead through Romeo, now the standard first Shakespeare text in many public schools. Here, too, we might imagine, it is not only the erotics and pains of young love but also the generational conflict that hold strong appeal.

What we might call the readiness for appropriation of the feud (“My parents don’t understand me”) was very much in evidence in the discussions that led up to the play’s most important intervention in modern, twentieth-century culture: the musical West Side Story, with book by Arthur Laurents, lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, and a compelling and memorable score by Leonard Bernstein, all based on a conception of the director and choreographer Jerome Robbins. (The fact that the original inspiration came from Robbins may say something about the legacy of Shakespeare’s play as a vehicle for dance.)

At the top of Leonard Bernstein’s copy of Romeo and Juliet, scrawled in the composer’s hand, is the annotation “An out and out plea for social tolerance.”27 The original idea for the adaptation of Shakespeare’s play, though, would have been called “East Side Story” rather than West Side Story. As the director and choreographer imagined the show and discussed it with Bernstein, the conflict was to be religious, rather than ethnic or racial: “When we started a project about Romeo and Juliet in the slums,” Bernstein told an interviewer, “the East Side was what we had in mind—a story about kids fighting in the streets of the Lower East Side of New York. We took the story from Shakespeare to that setting…. This was 1949. Arthur [Laurents] wrote a couple of scenes, and we began to see at a certain point that the show was dated. There was a faint odor of Abie’s Irish Rose [a long-running Broadway play of the 1920s about an Irish Catholic girl who marries a Jewish man over the objection of both of their families]. So we gave it up. Five years later the right time came.”28

The “right time” was the mid-fifties, and the place of inspiration Los Angeles, where an article in the Los Angeles Times, found at poolside at the Beverly Hills Hotel, offered the necessary spark: a headline in the paper described “Gang Riots on Oliveira Street, about Mexicans and so-called Americans rioting against one another.”29 Bernstein recalled suggesting that they do the musical about “the Chicanos,” and noting that there were Puerto Rican gangs in New York. Within a short time Robbins, Laurents, Bernstein, and a new young composer named Stephen Sondheim were on board to do West Side Story.

In the musical as it ultimately developed—a “musical tragedy,” as someone observed, rather than a “musical comedy”30—the feud is between the Jets and the Sharks, two rival gangs, the first gang presumptively white, the second gang Latino. Tony (Polish-American Anton) and Maria (from Puerto Rico) are the Romeo and Juliet. Anita, Maria’s friend from the bridal shop where they both work, is both the Nurse-confidante figure and an age-mate for Maria; her love for Maria’s brother Bernardo, who replaces Tybalt as the victim of Tony/Romeo’s ill-advised but well-intentioned intervention, gives Anita a powerfully tragic as well as a wittily knowing voice. Chino, Maria’s hapless suitor, is a version of Juliet’s suitor Paris, but with, again, a greater implication in the outcome, since it is Chino who kills Tony, precipitating the double tragedy. Riff, the leader of the Jets, is based in part on Mercutio—since his accidental death triggers the gang war—but Riff is from the first a partisan, not (as is the case with Mercutio) a kinsman of the Prince, and therefore a medial figure. The Friar Laurence of West Side Story is Doc, the owner of the drugstore where Tony works. Except for Doc, the clueless social worker Glad Hand, and Officers Krupke and Schrank, who represent all the repressiveness of a broken adult system, the entire cast is “young” (the printed cast list groups them last, in a category called “The Adults,” contrasted with “The Jets,” “Their Girls,” “The Sharks,” and “Their Girls”). Bernstein noted that casting the show was especially difficult “because the characters had to be able not only to sing but to dance and be taken for teenagers. Ultimately, some of the cast were teenagers, some were 21, some were 30 but looked 16.”31 In his diary at the time of the original rehearsals, he wrote: “I can’t believe it: forty kids are actually doing it up there on stage! Forty kids singing five-point counterpoint who never sang before—and sounding like heaven. I guess we were right not to cast ‘singers’: anything that sounded more professional would ultimately sound more experienced, and then the ‘kid’ quality would be gone. A perfect example of a disadvantage turned into a virtue.”32

Only occasionally does Shakespeare’s language surface directly in the text of West Side Story. Riff’s and Tony’s ritual greeting—“Womb to tomb!” “Sperm to worm!”—cleverly updates it, appropriating Friar Laurence’s sententiousness (and the encapsulated plot of the play) by translating his words into a racier, sexier idiom. The Friar’s lines are uttered to himself as he gathers herbs in his garden, oblivious to the ironic and predictive significance of his words: “The earth, that’s nature’s mother, is her tomb; / What is her burying grave, that is her womb” (2.2.9–10). Riff and Tony, who repeat this salute several times, use it as a kind of loyalty oath, expressing their lifelong (and deathlong) friendship. Family here is subsumed into gang affiliation: only when Bernardo is killed is blood relationship explicitly mentioned in the Sondheim lyric “A Boy Like That” (“A boy like that, / Who’d kill your brother…Stick to your own kind”). The Shakespearean plot, of course, is clearly recognizable—part of the point was to have the audience see the relevance of then to now, of great dramatic tragedy to musical theater (and of Shakespeare to Bernstein, Robbins, Laurents, and Sondheim). Tenement fire escapes offered an inspired urban equivalent to Juliet’s balcony.

But it is in energy, movement, tonality, and even body type that West Side Story makes its claims for modernity and youth as a kind of timeless timeliness. Just as Friar Laurence’s lines unwittingly predict the tragic plot of a story he does not yet begin to know, so also Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet is seen as a prescient precursor of youth culture. A movement then gathering strength in the still “conformist” but already restless fifties, with the civil rights movement rising through the end of the Eisenhower years, would lead, before the next decade was out, to the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the assassinations of three prominent American leaders, and the revolutions of ’68. All this still lay in the future as Bernstein and Robbins designed their fresh take on the Broadway musical, on dance and theater, on youth, on what Bernstein (in the unmistakable language of the fifties) called “social tolerance”—and on Shakespeare.

Irene Sharaff, the costume designer, described the way she differentiated the two gangs from each other onstage. “In the fifties, the teen-age boys one saw on the streets of New York had arrived at a uniform of their own—not yet taken up by fashionable men and women—consisting of blue jeans or chinos, T-shirts, windbreakers, and sneakers…. The modern windbreaker with ahood, particularly when worn with tight-fitting jeans, has a silhouette and line resembling that of figures in Florentine Renaissance paintings.”33 The Jets wore blues and ocher yellows, the Sharks purple, deep pink, red, and black. The Jets’ girls wore pastels; the Sharks’ girls, in brighter colors, carried the shawls, or rebozos, that marked them as Latino, and that became a sign of mourning when, in the last scene, they shrouded the girls’ heads. “The T-shirt,” Sharaff noted, “in the fifties was worn solely as underwear.” She dyed the shirts, faced the windbreakers with contrasting satin edging, and produced an indelible sign of period style. The period evoked then was “now.” Modernity. The immediacy and fragility of today.

But one of the many things that both West Side Story and Romeo and Juliet continue to demonstrate is that now is never now for long. The years between the writing of Sondheim’s lyrics for “Cool” in the mid-fifties and the emergence of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones in the early sixties marked a sea change in youth culture and sensibility. There was a way in which the fifties predicted the sixties, and a way in which the sixties took the fifties (them, us) by surprise. The most commonly cited cultural quotation from West Side Story today is almost undoubtedly Maria’s song “I Feel Pretty,” sung in the bridal shop, as she dresses for a reunion with Tony that will never come. “I Feel Pretty,” it is perhaps needless to say, has since become a camp classic. “I Feel Pretty” spinoff products are sold at the “West Side Story” online store (T-shirts in sizes small, large, and extra large; charm bracelets; wallets, cosmetics, and iPod cases, all in pink). Leonard Bernstein’s response to Shakespeare’s play—“an out and out plea for social tolerance”—sounds a little dated, and even a little sententious.

The next major adaptations of the play would be a) on film and b) concerned with youth, sexuality, media, and generational conflict. Shakespeare’s language, and Shakespeare’s characters and plots, are in Franco Zeffirelli’s and Baz Luhrmann’s films paradoxically fresher, sexier, and more contemporary than West Side Story’s dance at the settlement house gym or rumble under the highway. The dynamics of the feud, which took center stage in the conflict between the Jets and the Sharks, the Anglos and the Puerto Ricans, again receded, and was replaced by the love story of two young people and the failure of parents to understand their idealistic and rebellious children. Romeo’s outburst to Friar Laurence “Thou canst not speak of that thou dost not feel” (3.3.64) was, effectively, the cry of a generation.

THE SUPPOSED UNIVERSALITY of generational conflict—or rather, its rediscovery as a main theme of sixties political movements—gave renewed impetus to the play’s energies.

Bob Dylan’s song “The Times They Are a-Changin’” was copyrighted in 1963. It became the anthem for a generation. Its lyrics speak, almost uncannily, to the Romeo and Juliet situation:

Come mothers and fathers

Throughout the land

And don’t criticize

What you can’t understand

Your sons and your daughters

Are beyond your command

Your old road is

Rapidly agin’.

Please get out of the new one

If you can’t lend your hand

For the times they are a-changin’.

The line it is drawn

The curse it is cast

The slow one now

Will later be fast

As the present now

Will later be past

The order is rapidly fadin’.

And the first one now

Will later be last

For the times they are a-changin’.34

This logic of inversion (the slow will be fast, the present will be past, the sons and daughters will be in command) is, as we have already seen, the logic of Romeo and Juliet. And it is also—as should not now come as a surprise—the logic of the play’s intersections with modern culture.

In the second half of the twentieth century, and into the twenty-first, the play has been a favorite, even surpassing Hamlet or Lear, with both young people and edgy modern and postmodern movie directors (Zeffirelli, 1968. Luhrmann, 1996). And in these films the play’s internal instructions about the age of the protagonists have been taken as literally as possible. Zeffirelli’s Romeo, Leonard Whiting, was seventeen when he played the part, and his Juliet, Olivia Hussey, was fifteen. Leonardo DiCaprio was twenty-two and Claire Danes seventeen when Luhrmann’s film, with the stylishly updated title Romeo + Juliet, was released (which means they were a few months younger when it was filmed).

The Zeffirelli and the Luhrmann films spoke directly to their young audiences, as well as to the text and staging of Shakespeare’s play. Zeffirelli had directed the play on the London stage, with John Stride and Judi Dench as Romeo and Juliet in 1960, shortly after the success of West Side Story. The film version, in 1968, cast even younger actors in the title parts, aiming to approximate the ages specified in Shakespeare’s text. Psychological backstories were developed for other characters. Mercutio (John McEnery, in both play and film versions) was a striking figure, described as “manic and desperate” in the Queen Mab speech (1.4.53–95), and, “in sharp contrast to performance tradition,” as “not in control” of his language and associations.35 Lady Capulet, in Zeffirelli’s concept, was a key figure in the plot, unhappily married to an older man, attracted to the young Tybalt, and sexually competitive with her daughter.36 The film was thus, as one critic described it, a version of The Graduate set in Renaissance Verona (The Graduate came out in 1967, Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet the following year). Clearly recognized as a “youth movie,” it quickly became the standard representation of the play in middle schools and high schools.37

The actress Ali MacGraw described Zeffirelli’s 1968 film as a breakthrough. “The play is about the volatile pressures of youth. Zeffirelli deftly turned Shakespeare’s prose [sic] into the poetry of love. This is the first version to show Romeo and Juliet naked on their wedding night.”38 MacGraw’s remarks came in a program sponsored by Waldenbooks, “your best source for romance novels.” She was chosen as a spokesperson, we can presume, because of her relationship to another archetypal love story of the period, the love story called simply Love Story, with a screenplay and novel written by Erich Segal. Love Story, with a famous tagline (“Love means never having to say you’re sorry”) and equally famous first sentence (“What can you say about a twenty-five-year-old girl who died?”), has been described by booksellers as “the Romeo and Juliet of the twentieth century.”39 And in fact, as it happens, Erich Segal himself once played the part of Romeo: in a Harvard Players production in the summer of 1957, when he was twenty and a college student, some years before he imagined and wrote his screenplay.40

Baz Luhrmann’s film, made almost thirty years later, updated the mise-enscène and the sensibility, wittily taking the word “family” (which does not in fact occur in Shakespeare’s play) as the linchpin, and offering mug shots of two crime “families,” the Montagues and the Capulets. This device served the double purpose of a historical transposition and a list of roles, since many of the characters could be introduced, visually, before they appeared in action in the plot. Luhrmann, the Australian director of Strictly Ballroom (and also of Benjamin Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream), staged the opening prologue, written in the form of a sonnet, as a TV anchor’s news report:

Two households, both alike in dignity,

In fair Verona, where we lay our scene,

From ancient grudge break to new mutiny,

Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean….

Prologue 1–4

Verona, in this case, was Verona Beach, in southern California; the feud was between crime lords over control of the territory, and Mercutio (Harold Perrineau) performed the “Queen Mab” speech in drag, while Queen Mab herself and her capacity to inspire dreams were turned into drugs and drug-related visions and hallucinations. The Prince became Captain Prince, the chief of police; both the Prince and Mercutio were played by black actors. So the film was, in a parlance long outdated by the time of its release, “relevant.” It was also fast-paced, effective, and retained Shakespeare’s language, though some scenes were cut and others altered. The last scene was given to Romeo and Juliet alone (no Paris, no Friar Laurence), and as in the earliest Davenant revisions, the lovers encounter (rather than ironically miss) each other before they die. (“Welcome to Verona Beach, a sexy, violent other-world, neither future nor past, ruled by two rival families, the Montagues and the Capulets,” read the production notes, while the film’s tagline is Juliet’s, “My only love sprung from my only hate.”)

So it is that Romeo and Juliet, that “immature,” “fresh,” “pure,” and “early” work, both anticipates and responds to what sociologists and cultural analysts have come to call “youth culture,” or “youth subculture.” It may be too strong a claim to say that Romeo and Juliet has produced youth culture, but nonetheless the composite idea Romeo-and-Juliet does function, today, as a recognizable signifier: a signifier of young love, obstructed passion, “star-crossed lovers” (one cannot improve upon Shakespeare, that master modernist), parents who just-don’t-understand, peer groups who exert what we now so easily call “peer pressure.”

Theories of youth culture and subculture were emerging, in Britain and the United States, during the period of the 1950s and ’60s—just as West Side Story and then the Zeffirelli Romeo and Juliet moved to make connections between Shakespeare’s play and modern youth, as performers and as audiences. “The seemingly spontaneous eruption of spectacular youth styles,” wrote Dick Hebdige, “encouraged some writers to talk of youth as the new class.”41 In the fifties some sociologists saw the juvenile gang as compensating for the social achievements—success in school and work, parental status—that would otherwise have conferred self-esteem. Others noted a similarity between the gang and the parent culture, seeing in the values of the youth subculture distorted, exaggerated, or parodic versions of the “respectable” parental world.42 So youth cultures could be both versions of, and resistances to, the “adult” culture to which they were subordinate, and upon which, to a certain extent, they were dependent. In the sixties and seventies, needless to say, it became more difficult—or more contestatory—to say which was the dominant, and which was the sub. Hebdige, whose interest was sparked by what he called “spectacular subcultures” (teddy boys, mods and rockers, skin-heads), placed an emphasis on class and ideology, but also on display: the theatrical self-representation that identified these groups, both to one another and as apart from the majority culture.

But theater is not a direct transcription of society, either in Shakespeare’s time or in ours. We might recall that Leonard Bernstein and Arthur Laurents had their epiphany about making a version of Romeo and Juliet as a racial gang war as they sat by the pool at the Beverly Hills Hotel and happened to catch sight of a headline in a discarded newspaper. As Laurents later wrote, “In Shakespeare, the nature of the conflict between the two houses is never specified. We began with religion, but that was dropped in the roomy pool of the Beverly Hills Hotel. Instead the problems of Los Angeles influenced us to shift our play from the Lower East Side of New York to the Upper West Side, and the conflict to that between a Puerto Rican gang and a polymorphous self-styled ‘American’ gang.”43 They, too, became obsessed with the idea of “style,” in this case theatrical style. Although he conceded that “juvenile delinquency is not the most lyric subject in the world,” what they aimed for, Laurents said, was a “lyrically and theatrically sharpened illusion of reality,” emphasizing “character and emotion rather than place-name specifics and sociological statistics.” Faced with the fact that the entire second half of Romeo and Juliet depends upon Juliet taking a magic potion, a device that they thought “would not be swallowed in a modern play,” they determined to use Shakespeare merely as a “reference point” rather than a detailed blueprint. The idea that the potion might correspond to drug-taking—or that the plan might speak to an epidemic of teen suicide—would have to wait for another adaptation, another direction, or another generation.44

For Arthur Laurents, the updated version in his musical would embody “the character of today’s youth.” But as we have seen, the “character of today’s youth” (drugs, teen suicide, dumb parents, peer pressure, and hasty, irrevocable decisions) seems in many ways to have found its model, and its mode, in Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. The pattern is circular, not linear. “Today” is a shifter, a word that means something different depending upon when it is written or spoken (Laurents’s “today” was 1957, a half century ago). Nonetheless, the “today” quality of Romeo and Juliet, the play’s—and the myth’s—capacity to be both a predictor and a shifter, is one of the most remarkable manifestations of the phenomenon we have been calling Shakespeare and modern culture. To locate the particular modernity of Romeo and Juliet, its insistence on a “now” when you-just-don’t-understand, we need, in fact, to look not only at versions and adaptations of the story, but, in this age of sampling, advertising, and simulacra, at its citations and quotations.

The Reflections, a doo-wop group from Detroit, recorded their hit single, “(Just Like) Romeo and Juliet,” in 1964. The refrain was “Our love’s gonna be written down in history / A-just like Romeo and Juliet,” and the verses move from optimism (“Findin’ a job tomorrow mornin’” “Gonna show (gonna show) how much I love her” “I’m gonna put Romeo’s fame / Right smack-dab on a date”) to the imagination of loss:

If I don’t (if I don’t) find work tomorrow

It’s gonna be (gonna be) heartaches ’n’ sorrow

Our love’s gonna be destroyed like a tragedy

Just like Romeo and Juliet.45

We might notice that the parents, the feud, and all the other “blocking figures” have disappeared from this compact narrative: in this case the problem is finding work and “get(ting) myself straight,” and the phrase “Romeo and Juliet” is a recognizable shorthand for the perfect dyad of young love. (Try singing “Just like Troilus and Cressida,” or “Just like Paolo and Francesca,” or “Just like Petrarch and Laura,” to see how striking it is that this one work of early modern literature has made its way so successfully into the lexicon of modernity.) “(Just Like) Romeo and Juliet” enjoyed renewed bursts of popularity in the seventies and eighties, as other groups recorded and performed it. And in the 1980s another classic rock song called “Romeo and Juliet” was produced by the British band Dire Straits and became one of their best-known hits. The “lovestruck romeo” tells his story in the form of a “lovesong,” and thus creates a lyric version of the play-within-a-play:

You promised me everything you promised me thick and thin

Now you just say oh romeo yeah you know I used to have a scene with him.

Juliet when we made love you used to cry

You said I love you like the stars above I’ll love you till I die

There’s a place for us you know the movie song

When you gonna realize it was just that the time was wrong?

The lyric offers a fascinating (counter) historical trajectory, as the past and the present become enfolded, the one within the other. The phrase from a “movie song” being quoted, “there’s a place for us,” is from “Somewhere,” written by Stephen Sondheim for Tony and Maria in West Side Story. The “lovestruck romeo” of the Dire Straits rock song cites not the 1956 stage musical, but the movie made of that musical in 1961. So this “romeo” (lowercase) from the 1980s cites a song from the film made from a musical based upon Shakespeare’s play about Romeo and Juliet. Add to this the modern vernacular sense of “a scene,” meaning in this case a kind of relationship (with the implication that the relationship is slightly self-dramatized or self-dramatizing, or perhaps just a kind of social performance); “oh romeo yeah you know I used to have a scene with him.” The lyric is actually pretty close to Shakespeare’s play in some ways. “You said I love you like the stars above I’ll love you till I die” is a tight summation of Juliet’s “Gallop apace” speech in act 3, scene 2.

and when I shall die

Take him and cut him out in little stars,

And he will make the face of heaven so fine

That all the world will be in love with night

And pay no worship to the garish sun.

3.2.21–25

This is the passage that Robert F. Kennedy quoted in his tribute to his brother, the slain president, at the 1964 Democratic National Convention. Kennedy cited the passage directly, and with attribution; he also chose a variant reading, one authorized by the fourth quarto of the play (in contrast to the first three quartos and the Folio), but preferred by some editors, in which the “I” of line 21 is replaced by “he”: “When I think of President Kennedy, I think of what Shakespeare said in Romeo and Juliet: ‘When he shall die / Take him and cut him out in little stars / And he shall make the face of heaven so fine / That all the world will be in love with night.’”46 The voice through which Robert Kennedy speaks on this occasion, unselfconsciously, is Juliet’s. He is not “identifying” with any character; instead he is quoting “Shakespeare,” the play and the spirit of young love and loss within the play.

Cosmic or local, tragic or “tragic,” Romeo and Juliet has been, throughout its history and especially in its interactions with modernity, the story of a perfect love disrupted by circumstance: feud, plague, politics, parental opposition, unseemly haste, and unforeseen delay. That the “time was wrong,” in the words of the Dire Straits song, was a verdict that could attach to both the personal and the national tragedies. Over all of these quotations hovers that sense of “star-crossed lovers,” mentioned by the Prologue in the opening lines of Shakespeare’s play, that seems already to foreclose the valiant struggles of individuals against the future. Whether it is the “mature” actors onstage (and in early version onscreen) caught in tension with their youthful parts, or the transformation into wordless ballet that paradoxically restored “youth” to its performers, or the determined relevance of a stage musical that seemed already, by the time it concluded its run, almost out-of-date with the youth culture of its time, the play, like its protagonists, has been consistently too early and too late. By the middle of the twentieth century Romeo-and-Juliet had become a cultural macro, a widely and instantaneously recognizable term for passionate (and doomed) young love. It was not a surprise to see the suicide of singer Kurt Cobain of Nirvana and his relationship to his wife, Courtney Love, compared to the characters and plot of Shakespeare’s play.47

AS ONE MIGHT EXPECT, given its themes and content, Romeo and Juliet has provided rich fodder for social researchers. A phenomenon called “the Romeo and Juliet effect” was detected, in the early 1970s, by a team of psychologists investigating the relationship between parental interference and romantic love. The researchers found that “parental interference in a love relationship intensifies the feeling of romantic love between members of the couple,” and concluded that this situation, applying the “well-supported psychological principles” of “goal frustration and reactance” to the circumstances of romantic love, was “perhaps novel enough to justify a distinctive name—the Romeo and Juliet effect.”48 What’s in a name? Enough, at least, so that sociologists two decades later, in a highly technical “three-wave longitudinal investigation,” came to the conclusion that “no evidence was found for the Romeo and Juliet effect.” The earlier study was described as “classic,” but the goals of the studies, apparently, differed. The “Romeo and Juliet effect” authors, according to the later account, “found the positive effect of parental interference only for a measure of romantic love from which trust had been partialled. As such, it was more of a ‘need’ measure. We had a general measure of love, the Braker and Kelley (1979) love scale.”49 As this brief quotation will suggest, the study from 1992 was far more technical and less “literary” than the one dated twenty years earlier; in the first article the authors summarized Shakespeare’s plot, retold the myth of Pyramus and Thisbe, and cited Denis de Rougement’s Love in the Western World among the scholarly sources. The second article mentions “Romeo and Juliet” only as a term used by their predecessors; Shakespeare is not mentioned, although there is an epigraph from his Romeo and Juliet, printed as a block quotation, but mislineating the verse so it actually reads as prose.

Juliet: “O Romeo, Romeo! Wherefore art thou

Romeo? Deny thy father and refuse thy name;

Or, if thou wilt not, be but sworn my love, And

I’ll no longer be a Capulet.”

—from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet50

The mode of transcription and attribution makes it clear that the authors’ relationship to the play is attenuated at best, and the play is not otherwise footnoted or included in the sources. By this time, in other words, the key issue for these social scientists—reasonably enough, given their topic and professional training—was not Romeo and Juliet but “the Romeo and Juliet effect.” Their conclusion was that the support of parents, peers, and “social networks” help to stabilize romantic attachments. “Hazard analyses showed that the female partner’s perceived network support increased the stability of the relationships.” So much for Juliet’s despairing rejection of her mother and the Nurse. But the authors here, of course, are seeking a “positive” outcome rather than a tragic one. In its adoption into the ordinary language of social science, Shakespeare’s play has become not even a secondary but really a tertiary source.

That is also the case with the most current and perhaps most controversial adoption of the “Romeo and Juliet” brand, not by social scientists but by jurists and journalists, in the concept of the “Romeo and Juliet law.” These laws, which have been adopted by several states (Kansas in 1999. Connecticut, Florida, Indiana, and Texas in 2007), are an attempt to mitigate harsh penalties meted out to teenage lovers who had consensual sex when one of them was still a minor. Well-publicized cases, including one in Georgia, drew attention to the situation of individuals, typically young men in their teens, who have received lengthy jail sentences as “sex offenders” because the parents of their underage partners pressed charges. As one commentator noted, because of Juliet’s age, “even Romeo would be labeled a sex offender today.”51

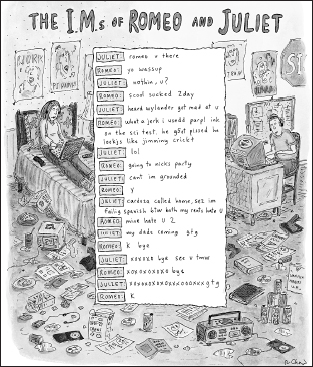

But as available as the play (or its title characters) has been to appropriation by social scientists, some of its most persistent avatars have been in the arts—not only in the “high culture” arts of dance and film, but also in the popular (and even “new media”) arts. Here are two brief but effective visual and aural examples that “sample” the play in, and for, the early twenty-first century—two examples that bring together the play’s cultural ubiquity (no one needs to be told the plot or who the protagonists are) with the key issues of haste, youth, and failed, private, or oblique communication. Modernity being what it is—and what it isn’t—the play’s famous declaration about “the two hours’ traffic of our stage” (usually quite a bit more) as an index of brevity are here sharply and wittily compressed into two minutes, or less—the time of a cartoon, a text message, or an advertising spot.

In a Roz Chast cartoon from The New Yorker, published on February 4, 2002, and entitled “The I.M.s of Romeo and Juliet,” the teenage Romeo and Juliet, both at their computers (she has a laptop, he has a Mac; it’s 2002, before the most recent portable technology), are sending instant messages to each other: “romeo u there,” asks Juliet, and he answers, “yo wassup.” She replies “nothin, u?” He asks if she’s going to a party, but she’s “grounded.” “Y” is the one-letter query—no question mark needed. And then it’s on to the family feud. “btw, both my rents hate u,” she writes. His parents, it seems, “hate u,” too. This cozy exchange is interrupted by the impending arrival of the heavy father: “my dads coming gtg,” she types. Here is where Chast’s cartoon intersects with the famous “balcony scene”:

Romeo and Juliet

Romeo: k bye

Juliet: xoxoxo bye see u tmw

Romeo: xoxoxoxoxo bye

Juliet: xoxoxoxoxoxxxoooxxx gtg

Romeo: k

Compare this dialogue to the Shakespeare text as we thought we once knew it:

Good night, good night. Parting is such sweet sorrow

That I shall say good night till it be morrow.

2.1.229–30

Chast’s cartoon perfectly captures, in the mode of the consciously bathetic, the distinctive quality of this famous scene: the repetitions, the delays, the digressions, the excuses, the pleasurable pain of parting: gtg k bye. The cartoon is not only a snapshot double reading of Shakespeare and modern culture, but also, potentially, a commentary on dialogue, monologue, audience, gesture, speech codes, and language. For a play that has become so much of a modern/postmodern cliché that it is regularly cited by those who have never read it, this rescripting calls attention to the paradoxical discursive role of Shakespeare in modern life.

Very much the same could be said of a television advertisement that was produced the following year and that likewise took off from a technology of modern speech and performance. In October 2003 Nextel Communications ran a Romeo and Juliet spot in conjunction with an advertising campaign promoting “push-to-talk” cell phones. The humorous premise of the campaign was that people would use the “push-to-talk” feature even in situations in which they were next to, rather than separated from, each other. The Romeo and Juliet commercial depicted various characters, in Renaissance costume, performing the entire plot of the play in thirty seconds. The words spoken were brief and telegraphic, a modern-age version of the classical (and Shakespearean) device of stichomythia. Each participant clasped a phone and spoke his or her lines into it:

|

Juliet: |

Romeo! |

|

Romeo: |

Juliet! |

|

Juliet: |

I love you! |

|

Romeo: |

Ditto. |

|

Tybalt: |

Die. |

|

Capulet: |

Marry him. |

|

Juliet: |

Never. [drinks potion]. |

|

Romeo: |

No! |

|

Paris: |

You! [attacks Romeo; Romeo slays Paris; Romeo drinks poison.] |

|

Juliet [awakening]: |

Better now. [Sees Romeo fall.] |

Friar Laurence: Kids.

[INTERTITLE: Nextel. Done.]52

I have arranged the lines here in some approximation of blank verse, since this tragedy-in-little is artfully designed to perform like a play. It takes two lines of iambic pentameter to get from love to death, with the Friar’s final line, spoken from above, hovering over the action like a futile and resigned benediction. The intertitle, as it appears on the screen, puts the “done” tag on both the love-death plot and Romeo and Juliet: nano-Shakespeare.

Where the New Yorker cartoon—a print medium—produced a script (with an ease that the struggling writer Will of Shakespeare in Love might have envied)—the television ad was, in essence, a very short movie. Like the rock or pop love song, these are among the art forms of our time.

Play, ballet, film, musical, rock song, cartoon, advertisement: Romeo and Juliet, a play that anticipated, documented, and to a certain extent scripted the concept of “youth culture,” has consistently found new genres, pertinent and impertinent, in which to stage the fraught dialogue between maturity and immaturity, experience and instinct, “we” and “you,” “now” and “then.” All of these terms are “shifters,” the term given by linguist Otto Jespersen to words whose referent can be understood only from the context. Ask the baby boomers and the flower children and the Gen-Xers, once forever young. “Youth culture” as a concept is both time-bound (originating in the sociology of the fifties) and in flux: you never step into the same generation twice.

Shakespeare’s plays are constantly aware of the “argument of Time,” from Falstaff’s “They hate us youth” (Henry IV, Part 2) uttered by that eternal optimist at the age of sixty, to Feste’s “Youth’s a stuff will not endure” (Twelfth Night), to Edgar’s “We that are young / Shall never see so much, nor live so long” (King Lear). But Romeo and Juliet live short, not long. It is the brevity and compression of their story, the impressionistic sense that their lives, and not only the play that bears their names, constitute a “two hours’ traffic” that has made this tragedy about untimely love so poignant, so “modern,” and so timely. As for modernity’s influence upon the play—that, we might say, is the real “Romeo and Juliet effect.”